Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (A-PXA, WHO grade III) is a newly defined entity with high-grade histopathologic features and a propensity for recurrence [6]. While PXA with low-grade histology (WHO grade II) can harbor a recurrent valine-to-glutamic acid (p.V600E) point mutation in BRAF in up to 78% of cases [6], the genomic drivers of A-PXA are poorly understood as the V600E mutation is absent in over half of A-PXAs [4]. Alterations reported to date in V600E-negative cases have included novel BRAF fusions and copy number alterations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genomic alterations in BRAF V600E-negative anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma

| Referencea | Number of cases | Method | Alteration (s) (cases/total tested) | Clinical outcome (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mistry et al., 2015 | 3 | WES, aCGH | CDKN2A HD (1/3) TP53 mutation (1/2) | No individual case data available |

| Phillips et al., 2016 | 2 | NGS | Case 1: NRF1-BRAF (1/2) Case 2: ATG7-RAF1 (1/2) CDKN2A HD (2/2) |

Case 1: GTR with recurrence, f/u 48 months, deceased Case 2: GTR with recurrence, f/u 15 months, alive |

| Alexandrescu et al., 2016 | 1b | FISH, methylation analysis (450 k) | CDKN2A HD Gains: + 5, 7, 9q, 12p, 14q, 16q, 22q Losses: −1, 6, 13q, 14q, 21q |

GTR, no recurrence, f/u 10 months, alive |

| Hsiao et al., 2017 | 1 | WES, transcriptome | TMEM106B-BRAF | Resection, PFS 6 months, field radiation, contralateral recurrence, STR, progression, chemo with TMZ, stable and alive |

| Vaubel et al., 2017 | 6 | Chromosomal microarray (OncoScan) | Gains: + 7 (3/6), + 5 (2/6) Losses: −22 (4/6), −14 (4/6), − 13 (3/6), − 10 (3/6), −1p (chromothripsis) CDKN2A HD (5/6) |

No individual case data available |

| Korshunov et al., 2017 | 20 b,c | Methylation analysis (450 k), targeted sequencing | TERT c.-124C > T (5/20); CDKN2A HD (8/20) | No individual case data available |

| Current study | 2 | WES, WGS, transcriptome | Case 1: BRAF p.L485_P490delinsF; FOXO1 p.A38T; HTR2A p.D48N; CDKN2A HD Case 2: BRAF p.V504_R506dup; KAT6A p.T1210 fs (subclonal) Gains (case 2): + 5, 6, 7, 10, 12, 15 Losses (case 1): −9, 22 |

Case 1: near-GTR, A9952 (carboplatin, vincristine), f/u 6 months, alive Case 2: subtotal resection, chemoradiation with TMZ, alive at last f/u 4 months post-dx |

WES whole exome sequencing, aCGH array comparative genomic hybridization, NGS targeted next-generation sequencing, IHC immunohistochemistry, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization, WGS whole genome sequencingm, HD homozygous deletion, PM promoter methylation, GTR gross total resection, f/u follow-up, PFS progression-free survival, STR stereotactic radiotherapy, TMZ temozolomide

asee Supplemental Material for reference citations

boverlapping cases

ccases initially diagnosed as epithelioid glioblastoma but clustered with PXA with methylome analysis

The efficacy of therapeutic targeting oncogenically activated kinases in BRAF-mutant cancers depends on structural variations in the kinase domain. For example, the BRAF V600E mutation is often sensitive to kinase inhibitors such as vemurafenib, while β3-αC deletions and non-canonical BRAF mutations are often resistant to this small molecular inhibitor [2]. Therefore, from a therapeutic aspect, it is imperative to define the spectrum of BRAF alterations in these aggressive tumors. Here, we report two newly identified A-PXAs with activating mutations in the β3-αC loop of the BRAF kinase domain discovered through whole-exome, whole-genome, and transcriptome sequencing (Michigan Oncology Sequencing Project [MI-ONCOSEQ]) [8].

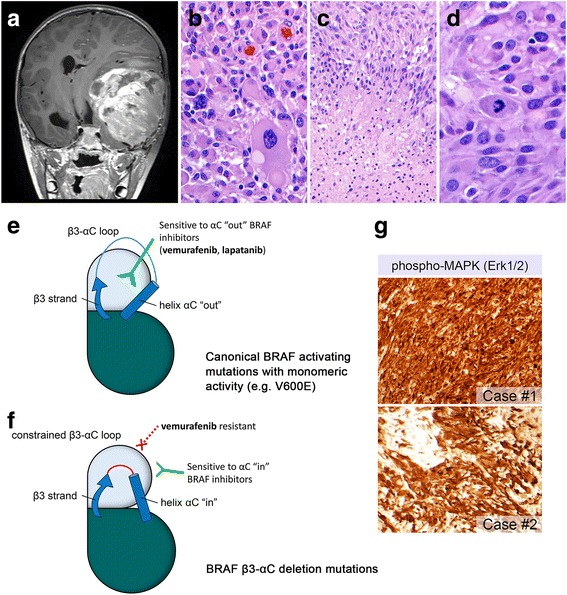

The first case is a 5-year-old male presenting with a large (11.7 × 7.3 cm) temporoparietal mass with subfalcine and uncal herniation (Fig. 1a). Molecular profiling revealed an oncogenic BRAF in-frame deletion (p.L485_P490delinsF) located adjacent to the β3-αC loop that results in a helix-constraining conformational change in the kinase domain. The second case is a 23-year-old male with a parietal ring-enhancing cystic mass. Sequencing revealed a novel 9 bp tandem duplication (p.V504_R506dup) in the β3-αC loop that results in a three codon in-frame insertion in the open reading frame (ORF) of BRAF [see Fig. 1a-d and Online Resource for details and representative images from both cases (Additional file 1)]. Consistently, both cases demonstrated MAPK activation with strong expression of phospho-ERK1/2 in tumor cells (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1.

A-PXA with non-V600E activating mutations affecting the β3-αC loop in BRAF. Post-contrast T1-weighted coronal MR sequence showing a large space-occupying lesion with significant midline shift (a). Histologic sections from case #1 demonstrated pleomorphic giant cells (b), as well as pseudopalisading necrosis (c) and increased mitotic activity (d). Illustration of conformational changes of the β3 strand and αC helix in the kinase domain. The canonical BRAF V600E mutation results in monomeric activity and can accommodate the oncogenic BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib, which only binds when helix αC is “out” (e). In β3-αC deletion mutations, the β3-αC loop is shortened, effectively locking helix αC in the “in” position and conferring resistance to vemurafenib (f) (modified with permission from Trends in Cancer, 2 (12), Foster SA, Klijn C, Malek S, Tissue-Specific Mutations in BRAF and EGFR Necessitate Unique Therapeutic Approaches, p. 699–701, 2016, Supplemental Reference [2] [Online Resource]). MAPK signaling pathway activation was confirmed with immunohistochemistry with anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK [Erk1/2] [Thr202/Tyr204] (g)

Both of the mutations reported here affect the β3-αC loop in the kinase domain. To function properly, protein kinases must maintain a level of structural flexibility in order to switch between inactive and active states. This conformational change involves two regulatory regions in the catalytic domain: the activation segment and the αC-helix [2]. During this process, the αC-helix undergoes an “out” to “in” shift that facilitates interaction with the β3 strand and initiates catalysis [2] (Fig. 1e). Case #1 demonstrated a deletion mutation in the BRAF β3-αC loop that results in a shortened αC-helix that constrains the loop conformation to a constitutively kinase active “in” state. Similar “in” state activating alterations have been reported in other major signaling pathway kinases including HER2 and EGFR [2]. β3-αC deletion mutations render tumors resistant to small molecule inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, that bind to and inhibit kinases with an “out” conformation, but are ineffective against the “in” state [1, 2] (Fig. 1e, f). Case #2 contained a mutation in a structural element (R-spine) of the αC-helix [9]. Mutations in the R-spine have been shown to stabilize the active state and result in constitutive kinase activation [3]. However, the effect of this mutation on the conformational state of the kinase domain remains to be determined. Because RAF dimers are often formed in tumors with β3-αC kinase loop alterations, RAF dimer inhibition has been proposed as an alternative therapy for these genetic alterations [10].

Recent reports of clinical responses in V600E-mutated A-PXAs with BRAF “out” inhibitors [5, 7] have been encouraging. However, selection of effective targeted therapies requires a mechanistic understanding of oncogenic kinase activation in tumors. We present two A-PXAs that contain BRAF β3-αC loop alterations that may not be sensitive to traditional BRAF inhibitors. Therefore, treatment approaches for A-PXAs with or without V600E mutations may differ depending on the specific type of BRAF genetic alteration.

Additional files

Clinical details, pathologic work-up, and sequencing methodology used in the current study. Figure S1. Additional histopathology from case #1 showed characteristic eosinophilic granular bodies (EGBs) (a) and an elevated proliferation index (Ki-67) (b). Immunohistochemistry for p16 showed loss of expression in tumor cells with retained expression in non-neoplastic cells (c, arrowhead), consistent with deletion of the INK4a locus. Staining with mutant-specific BRAF (VE1) was negative (d). Figure S2. Case #2 showed lipidized tumor cells and PAS-positive, diastase-resistant EGBs (arrowheads) (a). Nuclear pleomorphism and increased mitotic activity were seen (b, c). Neurofilament stain showing circumscription of the tumor mass (d). BRAF V600E was negative by IHC (e). Figure S3. MI-ONCOSEQ integrative sequencing report elements: somatic point mutations for case #1 (a) and #2 (c). Copy number plots for case #1 (b) and #2 (d). (DOCX 13229 kb)

Acknowledgements

The Venneti lab is supported by grants from NCI K08 CA181475, Mathew Larson, Sidney Kimmel, St Baldrick’s, Claire McKenna, Chad Tough, Doris Duke and Sontag Foundations and the University of Michigan Pediatric Brain Tumor Initiative.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Sequencing studies were performed at the University of Michigan after approval by our Institutional Review Board.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40478-018-0525-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Carl Koschmann, Email: ckoschma@med.umich.edu.

Sriram Venneti, Phone: (734) 763-0674, Email: svenneti@med.umich.edu.

References

- 1.Chen SH, Zhang Y, Van Horn RD, Yin T, Buchanan S, Yadav V, Mochalkin I, Wong SS, Yue YG, Huber L, et al. Oncogenic BRAF deletions that function as homodimers and are sensitive to inhibition by RAF dimer inhibitor LY3009120. Cancer Discovery. 2016;6:300–315. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster SA, Whalen DM, Ozen A, Wongchenko MJ, Yin J, Yen I, Schaefer G, Mayfield JD, Chmielecki J, Stephens PJ, et al. Activation mechanism of oncogenic deletion mutations in BRAF, EGFR, and HER2. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:477–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J, Stites EC, Yu H, Germino EA, Meharena HS, Stork PJ, Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Shaw AS. Allosteric activation of functionally asymmetric RAF kinase dimers. Cell. 2013;154:1036–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ida CM, Rodriguez FJ, Burger PC, Caron AA, Jenkins SM, Spears GM, Aranguren DL, Lachance DH, Giannini C. Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma: natural history and long-term follow-up. Brain Pathology. 2015;25:575–586. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee EQ, Ruland S, LeBoeuf NR, Wen PY, Santagata S. Successful treatment of a progressive BRAF V600E-mutated anaplastic pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma with Vemurafenib monotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:e87–e89. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathologica. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Migliorini D, Aguiar D, Vargas MI, Lobrinus A, Dietrich PY. BRAF/MEK double blockade in refractory anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Neurology. 2017;88:1291–1293. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roychowdhury S, Iyer MK, Robinson DR, Lonigro RJ, Wu YM, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Sam L, Balbin OA, Quist MJ, et al. Personalized oncology through integrative high-throughput sequencing: a pilot study. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3:111ra121. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tse A, Verkhivker GM. Exploring molecular mechanisms of paradoxical activation in the BRAF kinase dimers: atomistic simulations of conformational dynamics and modeling of allosteric communication networks and signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao Z, Torres NM, Tao A, Gao Y, Luo L, Li Q, de Stanchina E, Abdel-Wahab O, Solit DB, Poulikakos PI, et al. BRAF mutants evade ERK-dependent feedback by different mechanisms that determine their sensitivity to pharmacologic inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Clinical details, pathologic work-up, and sequencing methodology used in the current study. Figure S1. Additional histopathology from case #1 showed characteristic eosinophilic granular bodies (EGBs) (a) and an elevated proliferation index (Ki-67) (b). Immunohistochemistry for p16 showed loss of expression in tumor cells with retained expression in non-neoplastic cells (c, arrowhead), consistent with deletion of the INK4a locus. Staining with mutant-specific BRAF (VE1) was negative (d). Figure S2. Case #2 showed lipidized tumor cells and PAS-positive, diastase-resistant EGBs (arrowheads) (a). Nuclear pleomorphism and increased mitotic activity were seen (b, c). Neurofilament stain showing circumscription of the tumor mass (d). BRAF V600E was negative by IHC (e). Figure S3. MI-ONCOSEQ integrative sequencing report elements: somatic point mutations for case #1 (a) and #2 (c). Copy number plots for case #1 (b) and #2 (d). (DOCX 13229 kb)