Abstract

Air pollution causes severe physical and psychological health complications. Considering China’s continuously-deteriorating air quality, this study aimed to assess the self-reported effects of air pollution on the behavior and physical health of the students of 13 densely populated cities, and their awareness, practices, and perception of air pollution and its associated public health risks. A detailed, closed-ended questionnaire was administered to 2100 students from 54 universities and schools across China. The questionnaire, which had 24 questions, was categorized into four sections. The first two sections were focused on air pollution-associated behavior and psychology, and physical effects; while the final two sections focused on the subjects’ awareness and perceptions, and practices and concerns about air pollution. The respondents reported that long-term exposure to air pollution had significantly affected their psychology and behavior, as well as their physical health. The respondents were aware of the different adverse impacts of air pollution (respiratory infections, allergies, and cardiovascular problems), and hence had adopted different preventive measures, such as the use of respiratory masks and glasses or goggles, regularly drinking water, and consuming rich foods. It was concluded that air pollution and haze had negative physical and psychological effects on the respondents, which led to severe changes in behavior. Proper management, future planning, and implementing strict environmental laws are suggested before this problem worsens and becomes life-threatening.

Introduction

Air pollution is of serious concern across the globe, and is fueled by rapid population growth, continuous urbanization, increases in industrialization, continuous rises in energy demand, deforestation, and increases in car density, especially in major cities [1, 2]. Various anthropogenic activities lead to atmospheric degradation, such as emissions from vehicles, especially those that are older or poorly maintained; coal-powered industrial activities; construction, which produces dust; foundries and smelters; tobacco use; combustion that produces enormous heat; metal-based industries; mining; and excessive pesticide and chemical use [3–7]. This bleak scenario is further worsened through poor environmental management and regulation, use of inefficient technologies (with low production and high environmental deterioration), construction of congested roads, and the inability to strictly implement environmental regulations and laws, as well as a lack of awareness among the population about the serious health and psychological outcomes of pollution. This issue is even more prominent in underdeveloped and developing countries, where it is a serious concern as it adversely affects public health, alters the quality of life, and impacts the economy (by affecting agricultural production, for example) [8, 9].

Atmospheric heavy metals (lead, mercury, copper, zinc, cobalt, nickel, and cadmium), SO2, CO, NO2, benzene, particulate matter (PM), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), are the primary contributors to air pollution [7, 10–12]. The presence of these pollutants at levels beyond permissible limits causes serious health issues, such as breathing problems, allergies, cancers, cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, and even mortality [12, 13]. Elders, infants, toddlers, children, sensitive people, and those suffering from asthma and such other disorders are more vulnerable (physically and psychologically) to the effects of air pollution [14, 15]. Higher temperatures and air pollution are also associated with low mood and potency [16, 17], changes in sexual behavior, and negative effects on reproductive health [17, 18]. The World Bank [19] has provided an excellent updated insight of the fertility rate for all countries around the world, based on total births per woman, which could be linked to global warming/greenhouse gases and air pollution [17, 20, 21]. Kihal-Talantikite et al. [22] extensively reviewed the adverse impacts of proximity to polluted areas on the outcomes of pregnancy, such as infant mortality, premature birth, low birth weight, congenital malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, and gestational age. The physical effects associated with air pollution are widely studied, reported, and reviewed [23–28].

Numerous studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between air pollution and mortality across the globe, including in China [12, 29–32]. Researchers have reported that 3–7 million deaths over the past few decades were caused by cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) after continuous exposure to excessive levels of airborne PM [33–36]. Industrial power plants, vehicle emissions, fossil fuels, and biomass combustion have been identified as major sources of PM, which acts as a primary pollutant and a secondary product of different gases, including NH3, NOx, and SO2 [12, 27, 34, 35]. Time-series studies have assessed the association between daily mortality and ambient air pollution in different western countries [29, 37–39], and different major Chinese cities, including Hong Kong [40], Wuhan [31], Guangzhou [41], Shanghai [30], and Beijing [27].

Approximately 800 million people were affected by the hazardous dense haze (covering an area of 1.4 million km2) in January 2013, which generated serious concern about air pollution among the residents of Eastern China [15, 42]. Yang et al. [32] reported that 1.2–2 million deaths per annum in China are attributed to air pollution, which was the fourth most prominent cause of disability-adjusted lifespans. Lu et al. [43] reported that rapid industrial, urbanization, and population growth are major sources of China’s continuously-deteriorating air quality, and are posing a significant threat to public health. Approximately 65–75% of industrial powerhouses in China are still coal-operated (i.e., coal is a major fuel source), and are designated as major pollution sources [6, 44]. Owing to the current situation, air reporting systems have been developed and installed in 190 cities (945 sites) across China. This system reports air quality on an hourly basis, focusing on six air pollutants: PM2.5 (PM<2.5 μm), PM10 (PM<10 μm), SO2, NO2, O3, and CO. Estimating and understanding outdoor air pollutants and their burden on public health would help to control air pollution [13, 43].

Air pollution is one of the leading factors that upsets human emotions and alters behavior [45, 46]. Long-term exposure to polluted air results in a variety of psychological problems (such as stress, depression, anxiety, irritation, becoming short-tempered, and mood swings), which adversely affect behavior (such as eating, recreation, commuting, traveling, and socialization) [13, 23, 47, 48]. A recent study indicated that older people and females were suffered more and were more anxious because of low air quality than younger people and males [49]. Various studies have demonstrated the positive impacts of clean air on the human psyche, resulting in a pleasant mood and positive behavior [50]. Similarly, different studies have revealed a positive correlation between increased criminality (aggressive and violent behaviors) in humans and elevated temperatures (specifically in the summer) and air pollution [51–53]. Air pollution has also been correlated with depression, a serious mental disorder affecting people globally, which is continuously increasing [54]. Depression is characterized by a loss of pleasure and interests, guilt, sadness, inter alia, decrease in libido, disruption to sleep, and a loss of concentration [17]. There are several studies available that show a positive correlation between air pollution and depressive disorders that adversely affect human behavior [55–57].

Air pollution-associated mortalities [27, 32]; and age-, gender-, and season-dependent adverse impacts/effects of air pollution on humans [58–60] are well documented, but most of these studies focused on physical factors. Therefore, an effort was made to study the effects of air pollution on both the physical and psychological health of Chinese students using a detailed questionnaire, and the first two portions were dedicated to each physical and psychological health.

Material and methods

The study was conducted according to the Ethics Review Committee of Nanjing University (No. 2009–116). The Questionnaires were administered to the students following informed verbal consent. All participants were thoroughly informed of the purposes and contents of the project. All participants had the right to answer all or part of the questionnaire, and the right to stop participating at any time-point. They were requested to complete the questionnaires, then and there. Using questionnaire for data/information acquisition, the committee approves informed verbal consent, and hence it was considered to lessen time spent by the students or/and trouble to the students.

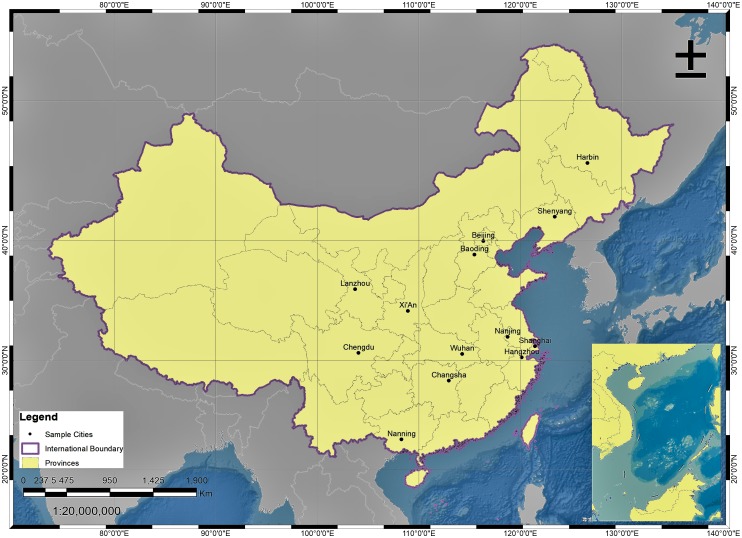

In this study, a comprehensive questionnaire (S1 File) was distributed to 2100 randomly-selected students from the chosen universities and schools. Questionnaires that shared identical answers to all questions, and those with a large number of missing answers, were excluded from the analysis. After removing these questionnaires, a total of 2048 questionnaires from 13 major cities across China were analyzed, including Beijing (Northern China), Baoding (Northern China), Nanjing (Eastern China), Shanghai (Eastern China), Hangzhou (Eastern China), Xi’An (Northwestern China), Lanzhou (Northwestern China), Harbin (Northeastern China), Shenyang (Northeastern China), Chengdu (Southwestern China), Nanning (Southern China), Changsha (Central China), and Wuhan (Central China). The sampled cities are indicated in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Geographical locations of the sampled cities.

The questionnaire contained a series of questions to elucidate the individual impacts of haze and air pollution on the physical and psychological (behavioral) health of the subjects. The questionnaire was prepared in two languages, English and Chinese. The questionnaire was split into four sections, two of which were dedicated to the effects of air pollution on behavior (caused by psychological adversity) and physical human health, while the final two assessed the respondents’ knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP); and sources of knowledge and perception of air pollution and its associated health risks. The survey was conducted over a period of six months, from October 2015 through March 2016. This period was selected because air pollution and haze are often at their highest during these six months.

Haze appears for ≥100 days per year in the Yangtze River Delta, and for ≥200 days in some of the studied Eastern China cities [25, 61, 62]. The surveyed cities were chosen as they are more densely populated (megacities) than other smaller cities. The primary data was obtained through the questionnaire that was administered to students of 54 different universities and schools, which had lived there for over a year, across the sampled locations. The subjects were approached at different points of the universities and schools, including campus areas, playgrounds, laboratories, cafeterias, classrooms, libraries, coffee shops, and waiting rooms, to ensure that individuals with different mood states at that time were included, so that the broader impact of pollution on them could be observed. Similarly, it was ensured that universities and schools situated near roadsides (transportation emissions), in heavily congested and industrialized areas (high levels of combustion, effluent emissions, and fossil fuel use), as well as those in less crowded areas, were included.

The data obtained were imported and analyzed by MS Excel, Origin Pro8.5, and Statistix (Version X) respectively. Based on the previous studies, a Chi-Square (independence) test was conducted to determine the association of gender and age with the responses to all sections of the questionnaire and examine gender- and age-dependent effects, perceptions, attitudes, and practices. Descriptive statistics (frequencies/proportion) were used to summarize the demographics of the respondents, their attitudes, practices, and perceptions to air pollution and its associated health risks, as well as the adverse effects of air pollution on their behavior (psychology) and physical health. A p-value below 0.05 (two-sided) was considered to be statistically significant. To avoid family-wise error, Bonferroni type adjustment (Bonferroni correction) was carried out by adjusting α value (αoriginal), by defining new α value (αaltered = 0.05/number of possible comparisons/analysis for each of the question, shown in Table A in S2 File). The map presenting the sampled cities was prepared in ArcGIS (V. 9.3).

Results

The study included a total of 2048 subjects, who were recruited from 54 universities and schools across China. The largest number of individuals was recruited from Nanjing (21.2%), followed by Beijing (12.5%) and Changsha (11.2%). It was ensured that participants from different age groups were included. Of the total respondents, 47.3% were 16–25 years old. The study considered both genders; 55.2% of the subjects were female, while 44.8% were male. Table 1 presents the demographics of the respondents that took part in this study. Table 2 shows the average of air quality pollutants for the sampled cities. Table B in S2 File shows the interquartile ranges for the air pollutants across the samples cities (Oct 2015—March 2016).

Table 1. Demographics of the respondents across sampling sites/cities.

| Cities | Universities/College | Gender | Age (Years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | 16–20 | 21–25 | 26–30 | 31–35 | ≥ 36 | ||

| Nanjing | 10 (18.5)* | 178 (40.8) | 258 (59.1) | 436 (21.2) | 232 (23.9) | 150 (15.4) | 38 (46.9) | 9 (60) | 7 (50) |

| Shanghai | 5 (9.2) | 62 (36.9) | 106 (63.1) | 168 (8.2) | 32 (3.3) | 135 (13.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Beijing | 10 (18.5) | 125 (49.1) | 130 (50.9) | 255 (12.5) | 193 (19.9) | 60 (6.1) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Hangzhou | 3 (5.5) | 52 (42.9) | 69 (57.0) | 121 (5.9) | 79 (8.1) | 39 (4.1) | 3 (3.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Xi’An | 5 (9.25) | 94 (50.6) | 88 (48.3) | 182 (8.8) | 40 (4.1) | 133 (13.7) | 9 (11.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Chengdu | 2 (3.7) | 27 (35.5) | 49 (64.5) | 76 (3.7) | 7 (0.7) | 66 (6.8) | 3 (3.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Baoding | 4 (7.4) | 65 (43.9) | 83 (56.1) | 148 (7.2) | 78 (8.1) | 70 (7.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nanning | 4 (7.4) | 47 (44.3) | 59 (55.6) | 106 (5.1) | 32 (3.2) | 73(7.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7.1) |

| Harbin | 2 (3.7) | 42 (48.8) | 44 (51.2) | 86 (4.2) | 78 (8.1) | 8 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lanzhou | 2 (3.7) | 52 (42.9) | 69 (57.1) | 121 (5.9) | 83 (8.5) | 38 (3.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Changsha | 4 (7.4) | 132 (57.6) | 97 (42.3) | 229 (11.2) | 62 (6.4) | 149 (15.4) | 13 (16.1) | 3 (20) | 2 (14.3) |

| Shenyang | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 30 (100) | 30 (1.5) | 0 | 18 (1.8) | 12 (14.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Wuhan | 2 (3.7) | 42 (46.7) | 48 (53.3) | 90 (4.4) | 54 (5.6) | 29 (2.9) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (13.3) | 4 (28.6) |

| Total | 54 (100) | 918 (44.8) | 1130 (55.2) | 2048 (100) | 970 (47.4) | 968 (47.3) | 81 (3.9) | 15 (0.7) | 14 (0.7) |

*Percentage given

Table 2. Air pollution across the sampled cities (Oct 2015–March 2016) (Mean±SD).

| Cities | Seasons | AQI | PM 2.5 (μg/m3) | PM 10 (μg/m3) | SO2 (μg/m3) | NO2 (μg/m3) | CO (mg/m3) | O3 (μg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanjing | Autumn* | 98.6±26.3 | 68.7±22.0 | 113.1±28.1 | 20.5±4.1 | 58.9±6.3 | 1.1±0.1 | 43.6±20.8 |

| Winter** | 106.3±5.7 | 74.5±5.3 | 123.0±8.7 | 22.1±2.5 | 53.3±6.2 | 1.3±0.1 | 51.9±12.6 | |

| Shanghai | Autumn | 89.2±19.7 | 62.6±18.1 | 79.7±18.4 | 18.8±5.1 | 56.7±9.4 | 1.0±0.2 | 53.3±28.5 |

| Winter | 84.5±10.9 | 58.6±9.5 | 78.8±5.3 | 18.9±3.6 | 48.7±7.1 | 0.9±0.2 | 65.5±14.5 | |

| Beijing | Autumn | 141.1±39.8 | 111.0±38.4 | 107.0±36.9 | 11.4±6.6 | 61.0±11.3 | 1.9±0.9 | 23.2±13.6 |

| Winter | 96.9±32.6 | 66.1±24.4 | 90.4±38.1 | 16.5±2.6 | 45.5±11.5 | 1.2±0.3 | 41.7±10.9 | |

| Hangzhou | Autumn | 87.1±26.5 | 62.5±21.3 | 93.9±29.2 | 15.9±2.6 | 53.6±6.3 | 1.0±0.2 | 36.8±22.9 |

| Winter | 94.7±8.1 | 67.7±7.3 | 107.9±10.8 | 14.2±1.3 | 49.8±11.0 | 0.9±0.1 | 48.9±16.8 | |

| Xi’An | Autumn | 115.0±32.0 | 75.8±28.4 | 160.7±44.7 | 29.4±12.7 | 51.4±7.6 | 2.1±0.7 | 20.4±7.0 |

| Winter | 131.1±21.2 | 86.2±23.3 | 180.0±30.1 | 31.5±7.0 | 53.9±8.7 | 2.3±0.7 | 31.7±8.3 | |

| Chengdu | Autumn | 88.5±22.6 | 63.4±18.9 | 104.7±27.7 | 16.0±1.3 | 53.0±8.2 | 1.1±0.2 | 26.1±13.7 |

| Winter | 99.4±6.2 | 70.4±6.7 | 118.4±10.0 | 15.4±2.0 | 54.1±6.7 | 1.3±0.0 | 41.5±11.7 | |

| Baoding | Autumn | 168.9±75.7 | 134.6±69.9 | 195.5±83.7 | 60.4±32.4 | 78.1±18.6 | 2.7±1.8 | 26.4±14.7 |

| Winter | 139.4±40.9 | 102.2±40.2 | 159.9±45.0 | 68.4±15.7 | 69.2±14.3 | 2.4±1.0 | 36.7±16.5 | |

| Nanning | Autumn | 64.05±13.6 | 41.23±9.6 | 74.92±24.9 | 14.15±2.4 | 35.28±3.5 | 1.03±0.01 | 37.07±12.7 |

| Winter | 69.9±10.1 | 48.6±9.2 | 76.0±9.4 | 12.9±2.0 | 34.3±3.5 | 1.1±0.1 | 35.9±10.0 | |

| Harbin | Autumn | 144.1±55.9 | 115.6±53.5 | 155.8±60.2 | 40.5±25.7 | 58.1±17.7 | 1.4±0.3 | 25.9±10.0 |

| Winter | 98.9±22.6 | 70.6±20.8 | 99.7±15.9 | 52.1±18.0 | 52.4±7.9 | 1.4±0.1 | 32.0±9.5 | |

| Lanzhou | Autumn | 90.6±14.4 | 57.5±17.5 | 116.7±16.5 | 25.3±9.0 | 55.7±10.8 | 1.7±0.6 | 30.9±8.2 |

| Winter | 101.8±12.3 | 55.2±8.5 | 136.4±22.6 | 23.7±10.4 | 49.0±7.2 | 1.5±0.4 | 48.6±13.8 | |

| Changsha | Autumn | 86.3±23.2 | 61.6±17.3 | 83.3±23.5 | 14.5±2.2 | 41.5±2.7 | 1.0±0.1 | 37.3±27.8 |

| Winter | 101.0±8.3 | 72.7±7.1 | 92.9±3.3 | 17.7±1.3 | 40.5±6.6 | 1.1±0.1 | 40.7±14.6 | |

| Shenyang | Autumn | 131.5±33.0 | 104.2±37.4 | 140.7±36.7 | 75.3±45.6 | 51.4±5.6 | 1.2±0.3 | 34.4±10.9 |

| Winter | 98.6±16.5 | 63.9±11.0 | 116.4±26.8 | 78.5±24.4 | 41.7±5.0 | 1.0±0.1 | 47.5±17.5 | |

| Wuhan | Autumn | 107.6±32.8 | 77.8±25.7 | 111.4±32.9 | 19.8±2.1 | 51.5±8.7 | 1.2±0.1 | 36.4±23.8 |

| Winter | 123.2±15.6 | 89.0±13.8 | 123.2±7.3 | 18.7±1.1 | 47.8±5.9 | 1.1±0.2 | 44.5±15.9 |

Autumn* = October to December 2015; winter** = January to March 2016

The first section of the questionnaire covered the adverse impacts of air pollution on the physical health of the recruited subjects. Of the total respondents, 88.9% reported that they have felt (always, often, and some of the time) the ill effects of air pollution, suggesting that air pollution is a major public health concern across China. The subjects suffered from different effects at varying magnitudes; 25.0% often suffered from sneezing, a dry throat, and eye irritation, and 34.0% occasionally experiences these effects. Of the total respondents, 62.0% had suffered (always, often, and sometimes) breathing problems and have faced respiratory problems. Fewer people suffered from coughing/wheezing and headaches/dizziness than those that have suffered from other ENT (ear, nose, and throat) problems. In total, 9.1%, 10.5%, and 24.6% of the respondents always, often, and sometimes felt that they had lower energy levels in response to air pollution, respectively. For sleeping patterns, 8.7%, 11.5%, and 23.4% of the respondents always, often, and sometimes faced problems in their sleeping patterns, respectively. Table 3 shows the reported physical health effects caused by air pollution, while Tables 4 and 5 contain gender- and city-, and age-dependent responses, respectively.

Table 3. Air pollution/haze caused physical health effects reported by the respondents.

| Physical effects | Always (%) | Often (%) | Sometimes (%) | Rarely (%) | Never (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felt air pollution effects | 622 (30.4) | 580 (28.4) | 618 (30.1) | 201 (9.8) | 27 (1.3) |

| ENT problems/irritation/allergies | 333 (16.3) | 510 (24.9) | 693 (33.8) | 414 (20.2) | 98 (4.8) |

| Respiratory problems | 241 (11.8) | 401 (19.6) | 627 (30.6) | 533 (26.0) | 246 (12.1) |

| Coughing or wheezing | 210 (10.2) | 390 (19.1) | 568 (27.7) | 604 (29.5) | 276 (13.4) |

| Headaches and dizziness | 174 (8.5) | 295 (14.4) | 567 (27.7) | 629 (30.7) | 383 (18.7) |

| Reduced energy level | 186 (9.1) | 217 (10.5) | 503 (24.6) | 632 (30.8) | 510 (24.9) |

| Sleeping disorder i.e., insomnia | 179 (8.7) | 236 (11.5) | 479 (23.4) | 596 (29.1) | 558 (27.2) |

Table 4. Gender & city-dependent physical effects of air pollution on the respondents.

| Gender | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | P-value* | χ2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | N | % | |||

| Effects of air pollution felt | ||||||||||||

| Male | 287 | 14.0 | 259 | 12.6 | 271 | 13.2 | 88 | 4.3 | 13 | 0.6 | 0.926b | 0.89 |

| Female | 335 | 16.4 | 321 | 15.7 | 347 | 16.9 | 113 | 5.5 | 14 | 0.7 | ||

| Sneezing, runny nose, dry throat, or eye Irritation | ||||||||||||

| Male | 134 | 6.5 | 236 | 11.5 | 305 | 14.9 | 182 | 8.9 | 61 | 2.9 | 0.003a | 15.60 |

| Female | 199 | 9.7 | 274 | 13.4 | 388 | 18.9 | 232 | 11.3 | 37 | 1.8 | ||

| Breath shortening or reduced lung function | ||||||||||||

| Male | 116 | 5.4 | 189 | 9.2 | 256 | 12.5 | 243 | 11.7 | 119 | 5.8 | 0.109b | 7.54 |

| Female | 124 | 6.3 | 212 | 10.4 | 371 | 18.1 | 290 | 14.2 | 126 | 6.2 | ||

| Coughing or wheezing | ||||||||||||

| Male | 101 | 4.9 | 181 | 8.8 | 241 | 11.8 | 258 | 12.6 | 137 | 6.7 | 0.181b | 6.24 |

| Female | 108 | 5.3 | 209 | 10.2 | 327 | 15.9 | 346 | 16.9 | 140 | 6.8 | ||

| Headache and dizziness | ||||||||||||

| Male | 85 | 4.2 | 125 | 6.1 | 249 | 12.2 | 270 | 13.2 | 189 | 9.2 | 0.167b | 6.46 |

| Female | 87 | 4.3 | 170 | 8.3 | 318 | 15.5 | 359 | 17.5 | 194 | 9.5 | ||

| Reduced energy level | ||||||||||||

| Male | 92 | 4.5 | 103 | 5.0 | 232 | 11.3 | 246 | 12.0 | 245 | 11.9 | 0.007b | 14.09 |

| Female | 92 | 4.6 | 114 | 5.6 | 271 | 13.2 | 386 | 18.8 | 264 | 12.9 | ||

| Sleep deprivation or sleeping disorders | ||||||||||||

| Male | 95 | 4.6 | 113 | 5.5 | 214 | 10.4 | 240 | 11.7 | 256 | 12.5 | 0.025b | 11.11 |

| Female | 84 | 4.2 | 123 | 6.0 | 265 | 12.9 | 356 | 17.4 | 301 | 14.7 | ||

| Adverse physical effects reported by the respondents across study sites/cities | ||||||||||||

| Nanjing | 400 | 13.1 | 490 | 16.1 | 929 | 30.5 | 770 | 25.3 | 453 | 14.9 | 0.000a | 368.18 |

| Shanghai | 226 | 19.2 | 167 | 14.2 | 313 | 26.6 | 272 | 23.1 | 198 | 16.8 | ||

| Beijing | 229 | 13.4 | 337 | 19.7 | 419 | 24.4 | 472 | 27.5 | 258 | 15.1 | ||

| Hangzhou | 67 | 7.9 | 132 | 15.6 | 247 | 29.2 | 240 | 28.3 | 161 | 19.0 | ||

| Xi’An | 170 | 13.9 | 223 | 18.2 | 348 | 28.4 | 291 | 23.7 | 195 | 15.9 | ||

| Chengdu | 44 | 8.3 | 92 | 17.3 | 175 | 32.9 | 158 | 29.7 | 63 | 11.8 | ||

| Baoding | 219 | 21.1 | 242 | 23.4 | 291 | 28.1 | 197 | 19.0 | 87 | 8.4 | ||

| Nanning | 55 | 7.3 | 205 | 27.3 | 217 | 28.9 | 156 | 20.7 | 119 | 15.8 | ||

| Harbin | 111 | 18.4 | 126 | 20.9 | 143 | 23.8 | 149 | 24.8 | 73 | 12.1 | ||

| Lanzhou | 81 | 9.6 | 162 | 19.1 | 268 | 31.6 | 204 | 24.1 | 132 | 15.6 | ||

| Changsha | 160 | 9.9 | 292 | 18.2 | 470 | 29.3 | 452 | 28.2 | 229 | 14.3 | ||

| Shenyang | 34 | 16.2 | 36 | 17.1 | 68 | 32.4 | 49 | 23.3 | 23 | 10.9 | ||

| Wuhan | 79 | 12.5 | 125 | 19.8 | 167 | 26.5 | 178 | 28.3 | 81 | 12.9 | ||

| Total Responses | 1875 | 13.2 | 2629 | 18.5 | 4055 | 28.5 | 3588 | 25.2 | 2072 | 14.6 | 14219 | |

* = bold value represents p-value < 0.05

a = p-value < αaltered (Significant after Bonferroni correction);

b = p-value > αaltered (Non-Significant after Bonferroni correction/adjustment)

Table 5. Age-dependent physical effects of air pollution on the respondents.

| Age range | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | P-value* | χ2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Effects of air pollution felt | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 293 | 29.9 | 262 | 26.8 | 300 | 30.7 | 107 | 10.9 | 16 | 1.6 | 0.577b | 14.29 |

| 21–25 | 286 | 30.6 | 273 | 29.2 | 280 | 29.9 | 87 | 9.3 | 9 | 0.9 | ||

| 26–30 | 33 | 31.7 | 34 | 32.7 | 29 | 27.9 | 6 | 5.8 | 2 | 1.9 | ||

| 31–35 | 4 | 25.0 | 4 | 25.0 | 7 | 43.8 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 6 | 40.0 | 7 | 46.7 | 2 | 13.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Sneezing, runny nose, dry throat, or eye Irritation | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 168 | 17.2 | 237 | 24.2 | 314 | 32.1 | 217 | 22.2 | 42 | 4.3 | 0.681b | 12.89 |

| 21–25 | 145 | 15.5 | 235 | 25.1 | 329 | 35.2 | 175 | 18.7 | 51 | 5.5 | ||

| 26–30 | 17 | 16.3 | 28 | 26.9 | 38 | 36.5 | 17 | 16.3 | 4 | 3.8 | ||

| 31–35 | 2 | 12.5 | 5 | 31.3 | 7 | 43.8 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 1 | 6.7 | 5 | 33.3 | 5 | 33.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 1 | 6.7 | ||

| Breath shortening or reduced lung function | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 130 | 13.3 | 190 | 19.4 | 275 | 28.1 | 265 | 27.1 | 118 | 12.1 | 0.395b | 16.85 |

| 21–25 | 99 | 10.6 | 191 | 20.4 | 300 | 32.1 | 238 | 25.5 | 107 | 11.4 | ||

| 26–30 | 10 | 9.6 | 17 | 16.3 | 39 | 37.5 | 24 | 23.01 | 14 | 13.5 | ||

| 31–35 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 6 | 37.5 | 4 | 25.0 | 4 | 25.0 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 13.3 | 7 | 46.7 | 2 | 13.3 | 2 | 13.3 | ||

| Coughing or wheezing | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 111 | 11.3 | 189 | 19.3 | 260 | 26.6 | 283 | 28.9 | 135 | 13.8 | 0.675b | 12.97 |

| 21–25 | 83 | 8.9 | 171 | 18.3 | 272 | 29.1 | 287 | 30.7 | 121 | 12.9 | ||

| 26–30 | 12 | 11.5 | 24 | 23.1 | 29 | 27.9 | 25 | 24.0 | 14 | 13.5 | ||

| 31–35 | 1 | 6.3 | 3 | 18.8 | 4 | 25.0 | 3 | 18.8 | 5 | 31.2 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 1 | 6.7 | 3 | 20.0 | 3 | 20.0 | 6 | 40.0 | 2 | 3.3 | ||

| Headache and dizziness | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 92 | 9.4 | 141 | 14.4 | 266 | 27.2 | 292 | 29.9 | 187 | 19.1 | 0.952b | 7.87 |

| 21–25 | 70 | 7.5 | 137 | 14.7 | 260 | 27.8 | 298 | 31.9 | 169 | 18.1 | ||

| 26–30 | 10 | 9.6 | 13 | 12.5 | 31 | 29.8 | 31 | 29.8 | 19 | 18.3 | ||

| 31–35 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 6 | 37.5 | 4 | 25.0 | 4 | 25.0 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20.0 | 4 | 26.7 | 4 | 26.7 | 4 | 26.7 | ||

| Reduced energy level | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 97 | 9.9 | 95 | 9.7 | 220 | 22.5 | 303 | 30.9 | 263 | 26.9 | 0.097b | 23.65 |

| 21–25 | 76 | 8.1 | 110 | 11.8 | 246 | 26.3 | 294 | 31.4 | 208 | 21.3 | ||

| 26–30 | 13 | 12.5 | 8 | 7.7 | 30 | 28.8 | 27 | 25.9 | 26 | 25.0 | ||

| 31–35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.3 | 5 | 31.3 | 5 | 31.3 | 5 | 31.3 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 20.0 | 2 | 13.3 | 3 | 20.0 | 7 | 46.7 | ||

| Sleep deprivation or sleeping disorders | ||||||||||||

| 16–20 | 105 | 10.7 | 99 | 10.1 | 208 | 21.3 | 275 | 28.1 | 291 | 29.8 | 0.013b | 31.12 |

| 21–25 | 62 | 6.6 | 125 | 13.3 | 243 | 25.9 | 273 | 29.2 | 232 | 24.8 | ||

| 26–30 | 12 | 11.5 | 8 | 7.7 | 21 | 20.2 | 36 | 34.6 | 27 | 25.9 | ||

| 31–35 | 1 | 6.3 | 2 | 12.5 | 3 | 18.8 | 5 | 31.3 | 5 | 31.3 | ||

| ≥ 36 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13.3 | 4 | 26.7 | 7 | 46.7 | 2 | 13.3 | ||

* = bold value represents p-value < 0.05

b = p-value > αaltered (Non-Significant after Bonferroni correction/adjustment)

The next section of the questionnaire was focused on the behavioral and psychological impacts of air pollution. In total, 62.1%, 78.1%, and 65.5% of the respondents suffered from depression/sadness/unpleasant moods, reduced exercise routines/jogging speed/jogging duration, and reduced walking speed, respectively, due to air pollution. A total of 1136 (55.4%) respondents reported that they feel anxiety and frustrated during hazy days. Of the total respondents, 44.1% reported that they become aggressive due to haze/air pollution, and a higher number reported that they exhibit more aggressive behaviors during warmer days (63.9%) than they do during colder days (27.6%). Table 6 shows the behavioral effects of air pollution noted by the respondents, while Tables C and D in S2 File show the reported gender- and city-dependent, and age-dependent effects, respectively.

Table 6. Behavioral and psychological effects caused by air pollution reported by the respondents.

| Behavioral effects | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Depressed | 1278 (62.4) | 770 (37.6) |

| Jog faster and for a short time | 1600 (78.1) | 448 (21.9) |

| Walk faster | 1341 (65.5) | 707 (34.5) |

| Anxiety | 1136 (55.5) | 912 (44.5) |

| Aggressiveness | 904 (44.1) | 1144 (55.9) |

| Aggressiveness during cold days | 566 (27.6) | 1482 (72.4) |

| Aggressiveness during hot days | 1308 (63.9) | 740 (36.1) |

The third section of the questionnaire contained questions about the preventive measures adopted by the respondents. Of the total respondents, 68.2% reported that they use a mask to cover their noses and mouths, 22.0% used eyeglasses/goggles to protect their eyes, 63.2% drink more water to help them flush out toxins (absorbed through the lungs/skin), and 65.2% indicated that they have a rich diet (high levels of vitamins C and E, and Omega-3-Fatty acids) to improve their immune response. Table 7 shows the practices adopted by the respondents to prevent the adverse impacts of air pollution, while Tables E and F in S2 File show the gender- and city-, and age-dependent practices, respectively.

Table 7. Preventive measures adopted to prevent the ill effects of air pollution.

| Preventive measures | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Use of respiratory mask (i.e., N95 (blocks about 95% of particles)) | 1396 (68.2) | 652 (31.8) |

| Wear eyeglasses or goggles | 451 (22.0) | 1597 (78.0) |

| Drink more water | 1294 (63.2) | 754 (36.8) |

| Build immunity with rich food | 1335 (65.2) | 713 (34.8) |

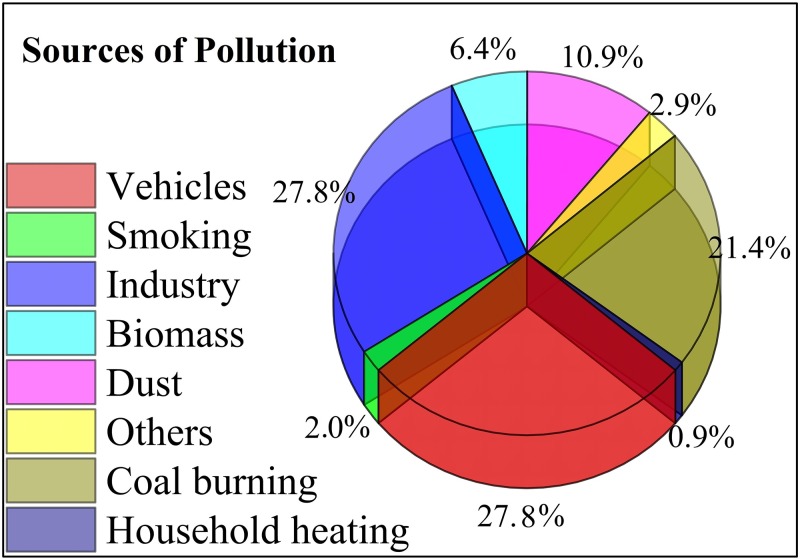

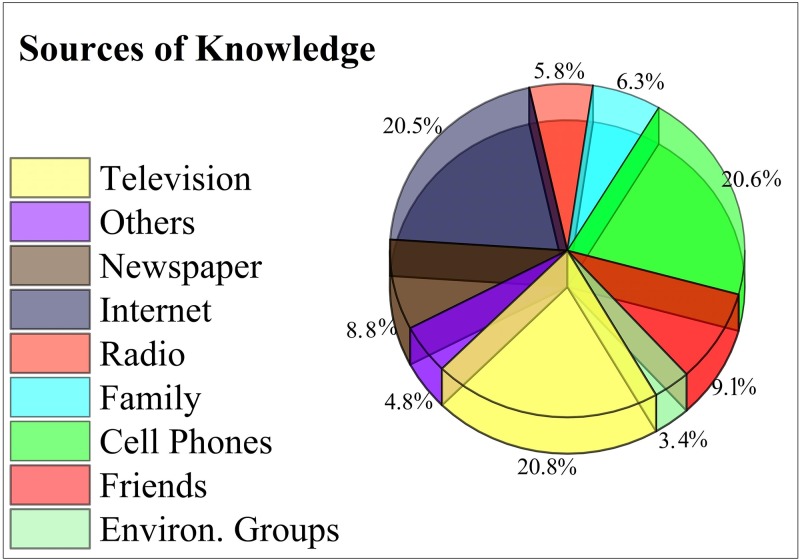

The final section of the questionnaire evaluated the recruited individuals’ awareness levels and perception of pollution. Of the total subjects, 96.0% reported that smoking should be banned in public areas and restricted to designated zones, 69.3% were aware that air pollution causes cardiovascular diseases and respiratory problems, such as lung cancer, and that air pollution was one of the major causes of mortality in China over the last two decades. Regarding industrialization, 68.8% of the respondents did not agree with compromising their health because of environmental and air pollution originating from China’s development, economic strength, and GDP growth from industrialization. Of the total subjects, 91.9% were aware of major pollutants, such as CO, SO2, and NO2. Vehicle exhausts (27.8%), industrial emissions (27.8%), and coal burning (21.4%) were identified as major sources of air pollution (Fig 2). Television (20.8%), cell phones (20.6%), and the internet (20.5%) were the leading sources of information about air pollution and its adverse health effects (Fig 3). Table 8 shows the respondents’ levels of awareness and perception of air pollution and its associated health risks, while Tables G and H in S2 File show the gender- and city-, and age- dependent knowledge and perceptions of air pollution, respectively.

Fig 2. Sources of pollution reported by the respondents.

Fig 3. Sources of knowledge reported by the respondents.

Table 8. Respondents’ levels of awareness and perceptions of air pollution.

| Awareness/Perception | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking should be prohibited | 1966 (96.0) | 82 (4.0) |

| Air pollution associated deaths | 1419 (69.3) | 629 (30.7) |

| Accept health loss over GDP growth | 640 (31.2) | 1408 (68.8) |

| Awareness about air pollutants | 1882 (91.9) | 166 (8.1) |

Discussion

China is currently facing prominent and complex issue of air pollution due to a rapid increase in urbanization and economic growth caused by heavy industrialization [43, 63, 64]. Environmental degradation could become more severe if proper management, environmental safety, and planning are not assured by environmental protection agencies, and the current scenario continues [11]. Over the past two decades, the infrastructure of almost all major Chinese cities has improved considerably, with extensive reconstruction in urban areas and modernization of industries [49]. In China’s major cities, subway systems are under development, along with other governmental and non-governmental infrastructures. The construction and expansion of these other infrastructures have attracted large numbers of workers from the countryside, elevating the population density of these cities. They have also resulted in an increase in urban air pollution, increasing the vulnerability of residents to adverse health effects [11, 65]. The ill-effects of long-term exposure to air pollution on human health, such as weakening/damaging the immune system, respiratory problems, low birth weight, and increased head circumference of children at birth, have been well-document [66–73]. Air pollution can cause mortality if different pollutants are present and exceed their permissible limits, for example, from continuous exposure to air containing 0.001% CO [74]. According to a report by the World Health Organization, urban air pollution (indoor and outdoor) contributes to over 2 million premature deaths per year [75]. According to the Global Burden of Disease study [26], of the 15 countries, China ranked first for premature mortalities (over 1.3 million premature deaths), which were attributed to ambient air pollution, while the preventable death rate was higher for Chinese megacities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, and Tianjin [76].

The aim of this study was to develop a more comprehensive model for the widely prevailing social problem of air pollution, which covered almost the whole of China, but specifically major cities. This study provides better insight for breaching the gap between public health KAP and scientific research than previous studies on this issue, as they were confined to certain places, such as a single city or province. However, our study was conducted in all of China’s major cities. This study strengthens the available literature [28, 49, 77] for all the relevant governing bodies, institutions, and agencies, and acts as a reference for mitigating the current scenario and preventing or reducing future risks and hazards caused by air pollution and its sources. According to Omanga et al. [78], an awareness of the public’s perception of pollution and its associated health risks is useful for designing and adapting suitable intervention programs.

Several studies have elucidated the impacts of air pollution on the respiratory system [68–70]. Respiratory disorders caused by air pollution include coughing, bronchitis, emphysema, and lung cancer [73], rendering individuals who are already suffering or have suffered from cardiac failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma, more vulnerable [79]. According to Botkin and Keller [80], those already suffering from respiratory disorders are the most vulnerable to air pollution. In this study, over 98% respondents reported that they have felt adverse physical effects (ranging from experiencing them all the time to rarely) due to air pollution; while only 1.3% responded that they never felt such effects. This signified that the sampled cities currently have poor and polluted air conditions. Other reported physical problems including flu (a runny nose), a dry throat, eye irritation, shortness of breath, reduced lung functioning, coughing/wheezing, headache/dizziness, reduced energy levels, and sleeping disorders. The severity of these problems reported by the respondents was in various ranges. The variation in these responses could be attributed to the health status of the individuals, variations in the pollution levels of the studied cities, and genetic polymorphism [81–83]. The reported results are consistent with those of previous studies, revealing the same adverse health effects from exposure to air pollution [34, 84, 85].

Positive psychological effects, better mental health, and appropriate behavior result from a suitable and clean environment, and comfortable weather conditions [50, 86–88], while an unhealthy environment has adverse effects on behavior and psychological and mental health, and causes abnormalities [55–57, 89, 90]. Polluted air exacerbates stress and depression, and alters behavior [14, 56, 73]. Sahari et al. [91] reported that poor atmospheric conditions (air and temperature) around living spaces and residential areas was a major cause of stress in humans. According to Brealey [92], stress is contagious, and is a physical and emotional response to pressure. Shahrom [93] described stress as a feeling of discomfort in oneself that influences the mind, however, according to Fadzillah-Kamsah, stress covers the following feelings: burden, worry, strain, conflict, pressure, feeling, fatigue, helplessness, panic, and depression [94]. Sahari et al. [94] comprehensively reviewed stress, and Łopuszańska and Makara-Studzińska [21] provided an overview of air pollution-associated depression.

Different stressors that trigger behavioral changes in humans have been explored. Tay and Smith [95] identified that peoples’ working styles, job nature, recreation methods, lifestyle, and local weather affected their behavior. Turkington [96] listed financial condition, family problems, social life, home problems, illness, time mismanagement, and job/career problems as primary factors affecting behavior. Shahroom [93] suggested that spiritual, social, physical, and biophysical factors affect behavior, while the most recent research revealed that environmental conditions (including air pollution and temperature) are primary stressors, as indicated by a number of researchers [46, 55–57, 91, 94, 97–98]. Torres and Casey [48] identified that mental health, affected by climatic changes or air pollution, is one of the main reasons for migration and disruption of social ties.

Air pollution has an adverse effect on outdoor and sporting activities that are practiced for maintaining an individual’s health and fitness [99]. In this study, it was reported that 78.1% of the respondents jogged faster and for a shorter duration on hazy days, while 65.5% walked faster in response to air pollution. Air pollution change behaviors associated with sports, such as going outside for games, exercise, and gymnasia. The stamina and physical strength required for partaking in sports are reduced by air pollution, as pollutants such as heavy metals and PM penetrate the lungs deeply and are not easily removed by exhalation, altering the duration and general willingness of people to partake in such activities [65]. To remove toxic pollutants, 63.2% of the respondents reportedly drank more water on hazy days, compared to normal or pollution-free days. There was no significant difference in water intake between different age categories and genders, which demonstrated that all respondents drank enough water to minimize the risks of air pollution, irrespective of their age and gender. Awareness and knowledge of air pollution might improve this scenario, and could encourage normal sporting behavior and change the attitude of the population towards air pollution-associated adverse human behavior [100].

Previous studies [101, 102] reported that the perception and knowledge of air pollution and its associated health risk were significantly different between different genders and the health status of the recruited individuals. There was a significant (p<0.05) difference between male and female responses to smoke prevention in public areas and compromising on air pollution caused by China’s GDP growth, while there was no statistically significant difference between the genders’ awareness of air pollutants and their associated diseases/disorders. There was a significant difference between the subjects’ awareness based on age, excluding awareness of major air pollutants. Significant (p<0.05) differences were observed between the respondents in the sampled cities, for all the sections of the questionnaire, which could be attributed to the differences in the levels of air pollution, access to media, and the local/provincial government’s outreach activities, such as seminars, symposia, and campaigns, regarding air pollution and its associated health risks. The differences in air pollution across the sampled cities could be caused by whether the city is a zone of production or consumption. Production sites are directly associated with trade (export/import, local/international), which elevates air pollution, as indicated by Wang et al. [12] and Zhang et al. [103]. Variations in the pollution level across China’s provinces could be caused by the county’s size. There are considerable differences between provinces, such as energy endowments and resources, lifestyles, population densities, and economic development. It was recently observed that, due to these factors, pollutants emissions increased rapidly in central China, while they stabilized or even decreased in coastal China [104–106].

A linear relationship between the knowledge or perceptions of air pollution’s adverse health impacts and literacy level has been reported [107, 108]. Some studies also reported that there was a marked difference in the subjects’ knowledge and perception of air pollution between income classes [109, 110]. Liu et al. [49] and Zhang [111] reported that women are more worried towards air pollution in China than men. In this study, there was a significant difference (p<0.05) between the preventative measures adopted by male and female subjects; the female respondents were more cautious towards air pollution as they practiced more preventative measures, such as the use of respiratory masks, goggles/glasses, drinking more water, and consuming nutrient-rich meals to boost their immunity, as compared to males. Similarly, Kim et al. [63] reported that younger people were less satisfied with air quality than older people, while Liu et al. [49] reported opposite findings. This contradiction could be due to variations in the health conditions of the respondents, as healthier subjects were less concerned, and their tendency to travel, as subjects with travel experience were more concerned and anxious about air pollution and its associated health risks [49]. In this study, no significant difference was observed in the awareness of air pollution and its associated health risks between age groups, excluding awareness of major air pollutants, but a significant (p<0.05) difference was observed between different age groups for awareness about toxic air pollutants.

The negative impacts of air pollution and its associated health risks can be minimized by increasing the public’s awareness. Internet sources (Baidu/blogs), social apps (Weibo/WeChat), and print or electronic media are useful tools for information transmission, exchange, and flow in China. By using such media, relevant literature and recommended practices against air pollution can be spread [112]. Similarly, informal communications; public conversations; discussions; and exchanging information between relatives, friends, and colleagues can also be vital in creating mass awareness and can positively influence the public’s risk perceptions. Health (doctors/physicians/other health care professionals) and social workers can also be included, as people often adopt health knowledge and practices from them. Based on this study, campaigns, seminars, symposia, and training about air pollution and its associated health risks should be arranged to increase awareness among the public and enable them of self-protection. Regular monitoring of air quality is suggested, as it can lead to fresh, clean, improved, and pollution-free air. During this study, the majority of the respondents reported television, their mobile phone, and the internet as their main sources of knowledge about air pollution and its associated health risks. The same response was reported by Liu et al. [49], however, Bickerstaff and Walker [113] reported that very few people selected media as their primary source of knowledge about air pollution. Although people do not check the air quality index on a regular basis, different reports, commentaries, and coverage about air pollution distributed through the internet, television, newspapers, radio, and magazines are educating people; changing their perception, attitude, and practices towards air pollution; and increasing their awareness of air pollution and its associated adverse health risks.

We attempted to approach as many subjects and to extend the study as broadly as possible, but, as other surveys, we faced some limitations (funding, time, and survey duration). Although the study covered 13 major Chinese cities, there are few rapidly developing cities that should also be surveyed. The current study was embodied to Chinese students only, so involving people other than the students is suggested in future studies. Moreover, for mental and behavioral health, the individual baseline physiological conditions were not adjusted on account of limited time frame, and tight schedule of Chinese students. Furthermore, the administered questionnaire contained closed-ended questions, therefore the responses were “as per asked” by the given questions. Therefore, surveying with an open-ended questionnaire is required to further extend our understanding of the population’s perceptions, attitudes, knowledge, and awareness level, and the problems they face, to determine how their consciousness towards self-protection can be enhanced. These key points must be considered before conducting this study in another area, and these findings should be cautiously applied to another location and population.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the recruited respondents have suffered from different, adverse physical effects, such as respiratory infections or problems (lung cancer, asthma), and different types of ENT illnesses, due to haze and air pollution. Owing to the current air pollution scenario, almost all of the recruited subjects used face/respiratory masks, some used eyeglasses/goggles to prevent the negative impacts of haze and air pollution, and many ensured that they drank enough water to avoid dehydration and remove toxins. The most severe responses to air pollution were psychologically-associated behavioral problems, indicating a serious threat to mental health, and behavioral vulnerability and variations induced by stress, depression, anxiety, shortened tempers, mood swings, and unpleasant moods. The respondents were aware of major air pollutants, their sources, and the adverse effects of haze and air pollution. Televisions, cell phones, and the internet were the primary sources of knowledge about air pollution and its associated health effects.

Governmental, such as environmental protection agencies, and non-governmental organizations should adopt effective communication styles to educate the public and increase their awareness and understanding of the health risks associated with air pollution at individual, family, and community levels. This will encourage them to adopt preventative measures, and safeguard themselves. This will also maximize the understanding of the public’s risk perceptions, which in turn will not have a negative effect on their behavior. The air quality assessment program should be extended to other parts of China, such as developing cities, which will aid in the acquisition of transparent data regarding air quality parameters in these sites, and will aid the development of proper strategies and plans to improve air quality across China. Coordination between governmental organizations and provincial governments, and their support to the central government is necessary and recommended for developing emission control policies to ensure that future generations do not face these problems.

Supporting information

(DOC)

Table A. Bonferroni Adjustments to remove family wise error inflation. Table B. Interquartile ranges for the air pollutants across the sampled cities (Oct 2016—March 2016). Table C. Reported gender & city-dependent behavioral and psychological effects of air pollution. Table D. Age-dependent behavioral and psychological effects of air pollution on the recruited respondents. Table E. Gender- and city-dependent adoption of practices to prevent the adverse effects of air pollution. Table F. Age-dependent adoption of practices to prevent the adverse effects of air pollution. Table H. Gender- and city-dependent awareness and perceptions of air pollution. Table G. Age-dependent awareness and perception of air pollution.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation (No. 31772470) of China in supporting the study financially. We are thankful to Dr. Xiaoguang Qi, Dr. Xinkang Bao, Dr. Donglai Li, Dr. Bingwan Liu, Dr. Aichun Xu, Dr. Min Chen, Dr. Zuofu Xiang, Dr. Zhenhua Luo, Dr. Junhua Hu, Dr. Aiwu Jiang, Dr. Yang Liu, Miss Runyang Zhang, Mr. Yunchao Luo, and Miss Lin Wang for their help in data collection. We also thank all the respondents, who participated in this survey and extend our meek thanks to Mr. Shoaib Khalid (Ph.D. (GIS) student, Nanjing University) for digitizing the map.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Sincere thanks to the National Natural Science Foundation (No. 31772470) of China in supporting the study financially to ZL. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cheng H, Gong W, Wang Z, Zhang F, Wang X, Lv X, et al. Ionic composition of submicron particles (PM1.0) during the long-lasting haze period in January 2013 in Wuhan, central China. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2014;26(4):810–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1001-0742(13)60503-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du Z, He K, Cheng Y, Duan F, Ma Y, Liu J, et al. A yearlong study of water-soluble organic carbon in Beijing I: Sources and its primary vs. secondary nature. Atmospheric Environment. 2014;92(Supplement C):514–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.04.060. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ullah S, Zuberi A, Alagawany M, Farag MR, Dadar M, Karthik K, et al. Cypermethrin induced toxicities in fish and adverse health outcomes: Its prevention and control measure adaptation. Journal of Environmental Management. 2018;206 (2018): 863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.11.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao G. The climatic characteristics and change of haze days over China during 1996–2005. Acta Geographica Sinica. 2008;63(7):761. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, Sutton DJ. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment Molecular, clinical and environmental toxicology: Springer; 2012. p. 133–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang D, Liu J, Li B. Tackling Air Pollution in China—What do We Learn from the Great Smog of 1950s in LONDON. Sustainability. 2014;6(8):5322 doi: 10.3390/su6085322 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oucher N, Kerbachi R, Ghezloun A, Merabet H. Magnitude of Air Pollution by Heavy Metals Associated with Aerosols Particles in Algiers. Energy Procedia. 2015;74(Supplement C):51–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.520. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen GF, Yuan SY, Xie YN, Xia SJ, Li L, Yao YK, et al. Ambient levels and temporal variations of PM2.5 and PM10 at a residential site in the mega-city, Nanjing, in the western Yangtze River Delta, China. Journal of Environmental Sciences and Health A Toxic/Hazardous Substances and Environmental Engineering. 2014;49(2):171–8. Epub 2013/11/01. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2013.838851 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo JP, Wu YR, Zhang XY, Li XW. [Estimation of PM2.5 over eastern China from MODIS aerosol optical depth using the back propagation neural network]. Huan jing ke xue = Huanjing kexue. 2013;34(3):817–25. Epub 2013/06/12. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EPHA. Air, Water Pollution and Health Effects. In: Alliance EPH, editor. London: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du X, Lu C, Wang H, Ma J. Trends of urban air pollution in Zhengzhou City in 1996–2008. Chinese Geographical Science. 2012;22(4):402–13. doi: 10.1007/s11769-012-0542-0 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, Zhang Y, Zhao H, Lu X, Zhang Y, Zhu W, et al. Trade-driven relocation of air pollution and health impacts in China. Nature Communication. 2017;8(1):738 Epub 2017/10/01. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00918-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szyszkowicz M, Willey JB, Grafstein E, Rowe BH, Colman I. Air pollution and emergency department visits for suicide attempts in vancouver, Canada. Environmental health insights. 2010;4:79–86. Epub 2010/11/17. doi: 10.4137/EHI.S5662 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho J, Choi YJ, Suh M, Sohn J, Kim H, Cho S-K, et al. Air pollution as a risk factor for depressive episode in patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or asthma. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;157(Supplement C):45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu F, Zhou L, Xu Y, Zheng T, Guo Y, Wellenius GA, et al. Short-term effects of air pollution on daily mortality and years of life lost in Nanjing, China. Science of the Total Environment. 2015;536:123–9. Epub 2015/07/24. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.048 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisch H, Andrews HF, Fisch KS, Golden R, Liberson G, Olsson CA. The relationship of long term global temperature change and human fertility. Medical Hypotheses. 2003;61(1):21–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00061-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO. Depression: A global crisis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen PJ. Effects of heat stress on mammalian reproduction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 2009;364(1534):3341–50. Epub 2009/10/17. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0131 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World-Bank. Fertility rate, total (births per woman). World Bank; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berreca A, Guidi M, Deschenes O. The conversation (Academic rigor, Journalistic flair) [Internet]2015. [cited October 2nd, 2017]. http://theconversation.com/climate-changes-hotter-weather-could-reduce-human-fertility-50273

- 21.Łopuszańska U, Makara-Studzińska M. The correlations between air pollution and depression. Current Problems of Psychiatry. 2017;18(2):100–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kihal-Talantikite W, Zmirou-Navier D, Padilla C, Deguen S. Systematic literature review of reproductive outcome associated with residential proximity to polluted sites. Internatioal Journal of Health Geography. 2017;16(1):20 Epub 2017/06/01. doi: 10.1186/s12942-017-0091-y . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling H-J. Psychological and physical impact of the haze amongst a malaysian community. Journal Sains Kesihatan Malaysia. 2008;6:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho RC, Zhang MW, Ho CS, Pan F, Lu Y, Sharma VK. Impact of 2013 south Asian haze crisis: study of physical and psychological symptoms and perceived dangerousness of pollution level. BMC psychiatry. 2014;14:81 Epub 2014/03/20. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-81 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao H, Wang S. Evaluation of Space-Time Pattern on Haze Polluttion and Associated Health Losses in the Yangtze River Delta of China. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies. 2017;26(4): 1885–1893. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England). 2012a;380(9859):2224–60. Epub 2012/12/19. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61766-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Li R, Li W, Wang M, Cao Y, Wu Z, et al. The association between ambient air pollution and daily mortality in Beijing after the 2008 olympics: a time series study. PloS one. 2013a;8(10):e76759 Epub 2013/11/10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076759 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Q, Baumgartner J, Zhang Y, Schauer JJ. Source apportionment of Beijing air pollution during a severe winter haze event and associated pro-inflammatory responses in lung epithelial cells. Atmospheric Environment. 2016;126:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.11.031. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominici F, McDermott A, Daniels M, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Revised analyses of the National Morbidity, Mortality, and Air Pollution Study: mortality among residents of 90 cities. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health A. 2005;68(13–14):1071–92. Epub 2005/07/19. doi: 10.1080/15287390590935932 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geng F, Hua J, Mu Z, Peng L, Xu X, Chen R, et al. Differentiating the associations of black carbon and fine particle with daily mortality in a Chinese city. Environmental research. 2013;120:27–32. Epub 2012/09/18. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.08.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong CM, Vichit-Vadakan N, Vajanapoom N, Ostro B, Thach TQ, Chau PY, et al. Part 5. Public health and air pollution in Asia (PAPA): a combined analysis of four studies of air pollution and mortality. Research Reports (Health Effects Institute). 2010; (154):377–418. Epub 2011/03/31. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England). 2013b;381(9882):1987–2015. Epub 2013/06/12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61097-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dockery DW, Pope CA 3rd, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(24):1753–9. Epub 1993/12/09. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pope CA 3rd, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Jama. 2002;287(9):1132–41. Epub 2002/03/07. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoek G, Krishnan RM, Beelen R, Peters A, Ostro B, Brunekreef B, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio- respiratory mortality: a review. Environmental Health. 2013;12(1):43 Epub 2013/05/30. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-43 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beelen R, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Stafoggia M, Andersen ZJ, Weinmayr G, Hoffmann B, et al. Effects of long-term exposure to air pollution on natural-cause mortality: an analysis of 22 European cohorts within the multicentre ESCAPE project. The Lancet. 2014;383(9919):785–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katsouyanni K, Touloumi G, Spix C, Schwartz J, Balducci F, Medina S, et al. Short-term effects of ambient sulphur dioxide and particulate matter on mortality in 12 European cities: results from time series data from the APHEA project. Air Pollution and Health: a European Approach. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;314(7095):1658–63. Epub 1997/06/07. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samoli E, Analitis A, Touloumi G, Schwartz J, Anderson HR, Sunyer J, et al. Estimating the exposure-response relationships between particulate matter and mortality within the APHEA multicity project. Environmental health perspectives. 2005;113(1):88–95. Epub 2005/01/01. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7387 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samoli E, Peng R, Ramsay T, Pipikou M, Touloumi G, Dominici F, et al. Acute effects of ambient particulate matter on mortality in Europe and North America: results from the APHENA study. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116(11):1480–6. Epub 2008/12/06. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11345 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong CM, Ma S, Hedley AJ, Lam TH. Effect of air pollution on daily mortality in Hong Kong. Environmental health perspectives. 2001;109(4):335–40. Epub 2001/05/04. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu ITS, Zhang Yh, San Tam WW, Yan QH, Xu Yj, Xun Xj, et al. Effect of ambient air pollution on daily mortality rates in Guangzhou, China. Atmospheric Environment. 2012;46(Supplement C):528–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.07.055. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu P, Chen Y, Ye X. Haze, air pollution, and health in China. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382(9910):2067 Epub 2013/12/24. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62693-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu J, Liang L, Feng Y, Li R, Liu Y. Air Pollution Exposure and Physical Activity in China: Current Knowledge, Public Health Implications, and Future Research Needs. International Journal of Environmental Researcn Public Health. 2015;12(11):14887–97. Epub 2015/11/28. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121114887 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kan H, Chen B, Hong C. Health impact of outdoor air pollution in China: current knowledge and future research needs. Environmental health perspectives. 2009;117(5):A187 Epub 2009/05/30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.12737 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reeve J. Understanding motivation and emotion: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miao Q, Bouchard M, Chen D, Rosenberg MW, Aronson KJ. Commuting behaviors and exposure to air pollution in Montreal, Canada. Science of the Total Environmental. 2015;508:193–8. Epub 2014/12/06. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.078 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harmatz MG, Well AD, Overtree CE, Kawamura KY, Rosal M, Ockene IS. Seasonal variation of depression and other moods: a longitudinal approach. Journal of biological rhythms. 2000;15(4):344–50. Epub 2000/08/15. doi: 10.1177/074873000129001350 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres JM, Casey JA. The centrality of social ties to climate migration and mental health. BMC public health. 2017;17(1):600 Epub 2017/07/07. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4508-0 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu X, Zhu H, Hu Y, Feng S, Chu Y, Wu Y, et al. Public's Health Risk Awareness on Urban Air Pollution in Chinese Megacities: The Cases of Shanghai, Wuhan and Nanchang. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health. 2016;13(9). Epub 2016/08/30. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090845 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guéguen N, Jacob C. ‶Here comes the sun″: Evidence of the effect of the weather conditions on compliance to a survey request. Survey Practice. 2014;7(5):1–6.26451335 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson CA. Heat and violence. Current directions in psychological science. 2001;10(1):33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohn EG, Rotton J. The curve is still out there: a reply to Bushman, Wang, and Anderson's (2005) "Is the curve relating temperature to aggression linear or curvilinear?". Journal of personality and social psychology. 2005;89(1):67–70. Epub 2005/08/03. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.1.67 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rotton J, Cohn EG. Outdoor Temperature, Climate Control, and Criminal Assault. Environment and Behavior. 2004;36(2):276–306. doi: 10.1177/0013916503259515 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Reviews Public Health. 2013;34:119–38. Epub 2013/03/22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vrijheid M. Health effects of residence near hazardous waste landfill sites: a review of epidemiologic literature. Environmental health perspectives. 2000;108 Suppl 1:101–12. Epub 2000/03/04. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim YH, Kim H, Kim JH, Bae S, Park HY, Hong YC. Air pollution and symptoms of depression in elderly adults. Environmental health perspectives. 2012b;120(7):1023–8. Epub 2012/04/20. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104100 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calderon-Garciduenas L, Calderon-Garciduenas A, Torres-Jardon R, Avila-Ramirez J, Kulesza RJ, Angiulli AD. Air pollution and your brain: what do you need to know right now. Primary health care research & development. 2015;16(4):329–45. Epub 2014/09/27. doi: 10.1017/s146342361400036x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gouveia N, Fletcher T. Time series analysis of air pollution and mortality: effects by cause, age and socioeconomic status. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health. 2000;54(10):750–5. Epub 2000/09/16. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.10.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeka A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Individual-level modifiers of the effects of particulate matter on daily mortality. American journal of epidemiology. 2006;163(9):849–59. Epub 2006/03/24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj116 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kan H, Heiss G, Rose KM, Whitsel EA, Lurmann F, London SJ. Prospective analysis of traffic exposure as a risk factor for incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116(11):1463–8. Epub 2008/12/06. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu CHC, Mao JT, Liu QH. Study on the distribution and seasonal variation of aerosol optical depth in eastern China by MODI. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2003;48(19):2094. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhai TY. Analysis of spatio-temporal variability of aerosol optical depth in the Yangtze River delta, China. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim M, Yi O, Kim H. The role of differences in individual and community attributes in perceived air quality. Science of the Total Environment. 2012;425:20–6. Epub 2012/04/10. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.03.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yixing Z, Ma LJC. China's Urbanization Levels: Reconstructing a Baseline from the Fifth Population Census. The China Quarterly. 2003;173:176–96. doi: 10.1017/S000944390300010X [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chaudhari PR, Gupta R, Gajghate DG, Wate SR. Heavy metal pollution of ambient air in Nagpur City. Environmental monitoring and assessment. 2012;184(4):2487–96. Epub 2011/06/15. doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2133-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang F, Li L, Krafft T, Lv J, Wang W, Pei D. Study on the association between ambient air pollution and daily cardiovascular and respiratory mortality in an urban district of Beijing. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health. 2011;8(6):2109–23. Epub 2011/07/22. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8062109 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kunzli N, Kaiser R, Medina S, Studnicka M, Chanel O, Filliger P, et al. Public-health impact of outdoor and traffic-related air pollution: a European assessment. Lancet (London, England). 2000;356(9232):795–801. Epub 2000/10/07. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02653-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fossati S, Metruccio F, Urso P, Ruggeri L, Ciammella M, Colombo S, et al. Effects of Short-term Exposure to Urban Particulate Matter on Cardiovascular and Respiratory Systems—The PM-CARE Study. Epidemiology. 2006;17(6):S528. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang H, Ye Y, Diggle P, Shi J. Joint Modeling of Time Series Measures and Recurrent Events and Analysis of the Effects of Air Quality on Respiratory Symptoms. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008;103(481):48–60. doi: 10.1198/016214507000000185 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gul H, Gaga EO, Dogeroglu T, Ozden O, Ayvaz O, Ozel S, et al. Respiratory health symptoms among students exposed to different levels of air pollution in a Turkish city. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2011;8(4):1110–25. Epub 2011/06/23. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8041110 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ling OHL, Saharuddin A, Kadaruddin A, Yaakub MJ, Ting KH. Urban Air Environmental Health Indicators for Kuala Lumpur City. Sains Malaysia. 2012;2012(41):2. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedersen M, Giorgis-Allemand L, Bernard C, Aguilera I, Andersen AM, Ballester F, et al. Ambient air pollution and low birthweight: a European cohort study (ESCAPE). The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2013;1(9):695–704. Epub 2014/01/17. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70192-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mabahwi NAB, Leh OLH, Omar D. Human Health and Wellbeing: Human Health Effect of Air Pollution. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014;153(Supplement C):221–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.10.056. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Enger ED, Smith BF. Environmental Science: A study of interrelationships. 7th ed Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 75.WHO. WHO air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide: Global assessment 2005: summary of risk assessment. In: Organization WH, editor. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lelieveld J, Evans JS, Fnais M, Giannadaki D, Pozzer A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature. 2015;525(7569):367–71. Epub 2015/09/19. doi: 10.1038/nature15371 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Howel D, Moffatt S, Prince H, Bush J, Dunn CE. Urban air quality in North-East England: exploring the influences on local views and perceptions. Risk Analysis. 2002;22(1):121–30. Epub 2002/05/23. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Omanga E, Ulmer L, Berhane Z, Gatari M. Industrial air pollution in rural Kenya: community awareness, risk perception and associations between risk variables. BMC public health. 2014;14:377 Epub 2014/04/20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-377 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abelsohn A, Stieb DM. Health effects of outdoor air pollution. Canadian Family Physician. 2011;57(8):881–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Botkin DB, Keller EA. Environmental science: earth as a living planet. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 81.London SJ. Gene-air pollution interactions in asthma. Proceedings of American Thoracic Society. 2007;4(3):217–20. Epub 2007/07/04. doi: 10.1513/pats.200701-031AW . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gilliland FD. Outdoor air pollution, genetic susceptibility, and asthma management: opportunities for intervention to reduce the burden of asthma. Pediatrics. 2009;123 Suppl 3:S168–73. Epub 2009/04/16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2233G . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sandstrom T, Kelly FJ. Traffic-related air pollution, genetics and asthma development in children. Thorax. 2009;64(2):98–9. Epub 2009/01/30. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.084814 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Donaldson K, MacNee W. The Mechanism of Lung Injury Caused by PM10. In: Hester RE, Harrison RM, editors. Air Pollution and Health. 10: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 1998. p. 21–32.

- 85.Jie Y, Kebin L, Yin T, Jie X. Indoor Environmental Factors and Occurrence of Lung Function Decline in Adult Residents in Summer in Southwest China. Iranian journal of public health. 2016;45(11):1436–45. Epub 2016/12/30. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keller MC, Fredrickson BL, Ybarra O, Cote S, Johnson K, Mikels J, et al. A warm heart and a clear head. The contingent effects of weather on mood and cognition. Psychological Sciene. 2005;16(9):724–31. Epub 2005/09/03. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01602.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Denissen JJ, Butalid L, Penke L, van Aken MA. The effects of weather on daily mood: a multilevel approach. Emotion (Washington, DC). 2008;8(5):662–7. Epub 2008/10/08. doi: 10.1037/a0013497 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guéguen N. Weather and courtship behavior: A quasi-experiment with the flirty sunshine. Social Influence. 2013;8(4):312–9. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2012.752401 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hsiang SM, Burke M, Miguel E. Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science (New York, NY). 2013;341(6151):1235367 Epub 2013/09/14. doi: 10.1126/science.1235367 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Woodward A, Smith KR, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chadee DD, Honda Y, Liu Q, et al. Climate change and health: on the latest IPCC report. Lancet (London, England). 2014;383(9924):1185–9. Epub 2014/04/08. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60576-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sahari SH, Yaman YM, Awang S, Awang R. Part-time adult students in Sarawak and environmental stress factors. Journal of Asian Behavioral Studies. 2012a;2:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brealey E. Ten minute stress relief. London: Casell; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shahrom MH. 7-day stress relief plan your road to recovery. Kuala Lampur, Malaysia: CERT Publications, SdnBhD; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sahari SH, Yaman YM, Awang-Shuib A-R. Environmental Stress among Part Time Students in Sarawak. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012b;36(Supplement C):96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.011. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tay SN, Smith PJ. Managing Stress: A Guide to Asian Living: Federal Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Turkington C. Stress management for busy people: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ismail R. [Stress AlamSekitar]. Malaysia: Dewan Bahasa danPustaka (DBP), Kuala Lampur; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mei NS, Wai CW, Ahamad R. Environmental Awareness and Behaviour Index for Malaysia. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2016;222(Supplement C):668–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.223. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li F, Liu Y, Lu J, Liang L, Harmer P. Ambient air pollution in China poses a multifaceted health threat to outdoor physical activity. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health. 2015;69(3):201–4. Epub 2014/06/28. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-203892 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wen XJ, Balluz L, Mokdad A. Association between media alerts of air quality index and change of outdoor activity among adult asthma in six states, BRFSS, 2005. Journal of community health. 2009;34(1):40–6. Epub 2008/09/30. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9126-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Badland HM, Duncan MJ. Perceptions of air pollution during the work-related commute by adults in Queensland, Australia. Atmospheric Environment. 2009;43(36):5791–5. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shi X. Factors influencing the environmental satisfaction of local residents in the coal mining area, China. Social Indicators Research. 2015;120(1):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Q, Jiang X, Tong D, Davis SJ, Zhao H, Geng G, et al. Transboundary health impacts of transported global air pollution and international trade. Nature. 2017;543(7647):705–9. Epub 2017/03/31. doi: 10.1038/nature21712 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu M, Wang H, Wang H, Oda T, Zhao Y, Yang X, et al. Refined estimate of China's CO2 emissions in spatiotemporal distributions. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2013;13(21):10873–82. doi: 10.5194/acp-13-10873-2013 [Google Scholar]

- 105.Feng K, Davis SJ, Sun L, Li X, Guan D, Liu W, et al. Outsourcing CO2 within China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(28):11654–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219918110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhao HY, Zhang Q, Guan DB, Davis SJ, Liu Z, Huo H, et al. Assessment of China’s virtual air pollution transport embodied in trade by using a consumption-based emission inventory. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2015;15(3):5443–56. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brody SD, Peck BM, Highfield WE. Examining Localized Patterns of Air Quality Perception in Texas: A Spatial and Statistical Analysis. Risk Analysis. 2004;24(6):1561–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ferreira S, Akay A, Brereton F, Cuñado J, Martinsson P, Moro M, et al. Life satisfaction and air quality in Europe. Ecological Economics. 2013;88(Supplement C):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.12.027. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Onkal-Engin G, Demir I, Hiz H. Assessment of urban air quality in Istanbul using fuzzy synthetic evaluation. Atmospheric Environment. 2004;38(23):3809–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2004.03.058. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fang M, Chan CK, Yao X. Managing air quality in a rapidly developing nation: China. Atmospheric Environment. 2009;43(1):79–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.064. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang J. Environmental hazards in the Chinese public's eyes. Risk analysis: an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis. 1994;14(2):163–7. Epub 1994/04/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vijaykumar S, Jin Y, Nowak G. Social media and the virality of risk: The risk amplification through media spread (RAMS) model. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. 2015;12(3):653–77. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bickerstaff K, Walker G. Public understandings of air pollution: the ‘localisation’of environmental risk. Global Environmental Change. 2001;11(2):133–45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Table A. Bonferroni Adjustments to remove family wise error inflation. Table B. Interquartile ranges for the air pollutants across the sampled cities (Oct 2016—March 2016). Table C. Reported gender & city-dependent behavioral and psychological effects of air pollution. Table D. Age-dependent behavioral and psychological effects of air pollution on the recruited respondents. Table E. Gender- and city-dependent adoption of practices to prevent the adverse effects of air pollution. Table F. Age-dependent adoption of practices to prevent the adverse effects of air pollution. Table H. Gender- and city-dependent awareness and perceptions of air pollution. Table G. Age-dependent awareness and perception of air pollution.

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.