Abstract

Selenium-enriched dietary supplements containing various selenium compounds are readily available to consumers. To ensure proper selenium intake and consumer confidence, these dietary supplements must be safe and have accurate label claims. Varying properties among selenium species requires information beyond total selenium concentration to fully evaluate health risk/benefits

A LC-ICP-MS method was developed and multiple extraction methods were implemented for targeted analysis of common “seleno-amino acids” and related oxidation products, selenate, selenite, and other species relatable to the quality and/or accuracy of the labeled selenium ingredients. Ultimately, a heated water extraction was applied to recover selenium species from non-selenized yeast supplements in capsule, tablet, and liquid forms. For selenized yeast supplements, inorganic selenium was monitored as a means of assessing selenium yeast quality. A variety of commercially available selenium supplements were evaluated and discrepancies between labeled ingredients and detected species were noted.

Keywords: Selenium, Dietary supplement, Speciation, LC-ICP-MS

1. Introduction

Within the scientific community, the essential element selenium (Pinsent, 1954) continues to be a topic of interest and debate. The health impact of selenium is multifaceted and complicated by its narrow range between toxic and beneficial effects, as well as its uneven distribution among the earth’s crust (Rayman, 2004, 2008). Currently in the United States, the Institute of Medicine and other entities recommend 55 μg/day for adults (Dietary Reference Intake (DRI), 2000; Hurst et al., 2013). Selenium plays a vital role as an antioxidant, in proper organ function and development, and although recently questioned, (Vinceti et al., 2014) is a possible chemopreventor (Clark et al., 1996). The Tolerable Upper Intake Level for adults is 400 μg/day with some evidence that selenium intake above this can increase occurrence of alopecia, dermatitis and type-2 diabetes (Dietary Reference Intake (DRI), 2000; Rayman, 2012).

Regardless of definitive evidence for selenium’s health benefits/ risks, the importance of controlling selenium intake, coupled with its possible chemopreventive nature, has no doubt contributed to an increase in marketing selenium-enriched dietary supplements. These supplements are commercially available to the public from a plethora of sources, in numerous dosage forms, and containing a variety of selenium species. The various forms of selenium dictate the role and efficacy of the functions it carries out (Fairweather-Tait, Collings, & Hurst, 2010).

Supplements commonly include selenium in the forms selenite (Se(IV)) or selenate (Se(VI)) (referred to as inorganic selenium (iSe)), selenomethionine (SeMet), Se-methylselenocysteine (MeSeCys), and selenized yeast (Se-yeast). Specifics vary among studies, but in general, inorganic forms of selenium (iSe) are absorbed less effectively than the organic forms, with the latter being slightly less toxic (Dietary Reference Intake (DRI), 2000; Tiwary, Stegelmeier, Panter, James, & Hall, 2006). Selenocysteine (SeCys) and SeMet have been shown to be incorporated into proteins in humans and plants (Cheajesadagul, Bianga, Arnaudguilhem, Lobinski, & Szpunar, 2014). To our knowledge, SeCys is not commercially available as a standard or dietary supplement. Recent debates have suggested reported findings of selenocystine (SeCys2, a commercially available standard, not typically listed as a dietary supplement ingredient) may be incorrect, including possible confusion with SeCys (Dernovics & Lobinski, 2008). There are other reports of common selenium species in supplements such as phenylselenocysteine, methaneseleninic acid (methylseleninic acid, MSeA), and selenocyanate (Gosetti et al., 2007), but obtaining supplements labeled to contain these ingredients proved to be difficult.

Se-yeast has been reported to contain over 60 unique selenium species (Arnaudguilhem et al., 2012) and for virtually all yeast types tested, SeMet was the most abundant. The lack of a formal definition of Se-yeast and the extensive variation of types complicates any verification. Bierla, Szpunar, Yiannikouris, and Lobinski (2012) noted that the typical criteria for Se-yeast of industrial use is >60% SeMet and <2% iSe of the total selenium. Currently, FDA regulates Se-yeast related to animal feed additives for which iSe must be <2% of total selenium (Selenium, 2015). Inorganic selenium content >2% could indicate a lower quality Se-yeast (Bierla et al., 2012).

Recent publications have noted that many selenium supplements available to the public either do not contain the labeled amount of selenium or lack the labeled form (Bakirdere, Volkan, & Ataman, 2015; Gosetti et al., 2007; Niedzielski et al., 2016). Total selenium content can routinely be determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric (ICP-MS) analysis. A greater challenge lies in quantifying the individual species, which is often complicated by the conversion that may occur during storage or extraction of the supplement. Many publications have examined selenium speciation in various matrices and this topic has been well reviewed (Wuilloud & Berton, 2014).

For dietary supplements, a variety of extraction/dissolution procedures have been employed, including water, acid, and enzymatic mixtures. Enzymatic extracts are commonly used for Se-yeast samples, but batch variability of proteases can lead to inconsistent recoveries and require rigorous control of conditions for optimal operation (Bierla et al., 2012). Bakirdere et al. (2015) reported that water, dilute hydrochloric acid, and enzymatic extractions all achieved comparable extraction efficiencies for non-Se-yeast labeled tablets. Methane sulfonic acid (MSA) has previously been demonstrated to extract SeMet from the selenized yeast reference material SELM-1 (Mester et al., 2006) and other Se-yeast sources (Barrientos, Wrobel, Guzman, Escobosa, & Wrobel, 2016). A basic extraction using sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was applied to selenium-enriched animal feeds with some success (Stadlover, Sager, & Irgolic, 2001). One primary goal of this project was to use a one-step extraction to quantitatively extract the compounds of interest while preserving their in situ forms; therefore multiple extractions were explored each with various limitations as subsequently explained.

Following extraction, multiple separations are typically needed to resolve the selenium species of interest using ICP-MS for detection. The most commonly used separation methods are reversed phase ion pairing (RP-IP), anion exchange, and cation exchange. The work by Niedzielski et al. (2016) examined 86 selenium fortified supplements for iSe versus the organic forms, but they did not distinguish among organic species. The report by Bakirdere et al. (2015) separated Se(IV), Se(VI), SeMet and SeCys2, while Hsieh and Jiang (2013) included MeSeCys; neither report accounted for the oxidized form of SeMet (SeOMet) or other related degradation products. Gosetti et al. (2007) examined a few supplements using LC-MS/MS, but multiple extractions, chromatographic separations, and relatively long analysis time made this method less attractive as a routine method. In general, anion exchange methods have difficulty resolving organic selenium compounds while RP-IP methods are limited by the resolution of iSe and SeCys2. While many research groups have utilized similar methodology to examine yeast based supplements, often with the objective of identifying the gamut of interesting selenium species (Goenaga Infante et al., 2004; Larsen, Hansen, Fan, & Vahl, 2001; Larsen et al., 2004); this approach is not desirable for routine analysis. With a few exceptions, separations published in the selenium supplement field have not considered common oxidation products or adequate support for SeCys2 identification. The other primary goal of this work is to develop a simple, robust, and more efficient method for routine detection of targeted selenium species commonly present or claimed present in selenium-enriched dietary supplements.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents and standards

Water used throughout the experiments was ultrapure deionized water with resistance >18 MΩ·cm obtained from a Milli-Q system (Bedford, MA, USA). All chemicals were reagent grade or higher. For total selenium analysis, samples were digested using Optima grade concentrated nitric acid and 30% (w/w) hydrogen peroxide both from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Individual standards of selenium species, including Se(IV) and Se(VI), were obtained from Inorganic Ventures (Christiansburg, VA, USA) at concentrations ca. 10 μg/mL. SeMet and SeCys2 were purchased from Acros organics (Fisher Scientific) and stock solutions were prepared in degassed water and 0.1% hydrochloric acid (Optima grade, Fisher Scientific), respectively. Se-methylselenocysteine hydrochloride (MeSeCys) was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA) then diluted in degassed water. Methylselenomethionine (MeSeMet) was prepared similar to Wrobel, Wrobel, Kannamkumarath, and Caruso (2003) and SeOMet was synthesized based on Larsen et al. (2004). The oxidized form of Semethylselenocysteine (MeSeOCys) and MSeA were prepared by adding 50 μL of H2O2 to 5 mL of 10 μg mL−1 MeSeCys; after 20 min, the primary product was MeSeOCys and after 16 h MSeA was the primary product. The concentrations of the selenium species are described on a total selenium concentration basis rather than the molecule as a whole. Total selenium concentrations of each stock solution were verified versus NIST traceable selenium standards (MES-2A, Spex Certiprep, Metuchen, NJ, USA) and NIST 1643e (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). For speciation analysis, mobile phase components included ammonium acetate (Fisher Scientific), tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAH, Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA), acetic acid, methanol (Fisher Scientific), pyridine (Fisher Scientific), and formic acid (Fisher Scientific). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrochloric acid (HCl), hexane and MSA were used for extraction and obtained from Fisher Scientific. For the bioaccessibility extraction, pepsin, pancreatin, bile salt, and ammonium carbonate were obtained from Sigma.

2.2. Samples

A total of 13 dietary supplements labeled to be selenium-enriched were purchased through various reputable online retailers; peer to peer transactions were avoided. The labeled selenium ingredients included SeMet, MeSeCys, selenium amino acid complex or chelates, selenium yeast, selenate, or selenite, and are summarized in Table 1. The form of the supplement included liquids, a tablet, capsules, and softgels. Additionally, SELM-1 (NRC, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) was used as a reference, primarily for total selenium analysis. SELM-1 is certified for SeMet, but the SeMet is incorporated into the yeast proteins. To our knowledge, no applicable non-Se-yeast SRMs were available for selenium speciation. Unless otherwise noted, intact individual dosage forms were analyzed, as opposed to composites; this allowed for the examination of dose to dose variability of a given supplement. When determining average sample weight of capsules and softgels, the dosage form weight was determined by differential weighing of intact dosage forms compared to empty outer shells. Capsule and softgel shells were not suspected to be a significant source of selenium and were not analyzed.

Table 1.

List of dietary supplements examined in this study. All were labeled to contain selenium in various forms.

| Sup. # | μg Se Dose−1 | Labeled Species | Dosage Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | Selenite | Liquid |

| 2 | 100 | Selenate | Liquid |

| 3 | 150 50 |

Selenate SeMet |

Tablet |

| 4 | 200 | SeMet | Capsule |

| 5 | 100 | SeMet* | Capsule |

| 6 | 200 | MeSeCys | Capsule |

| 7 8 | 200 200 | MeSeCys Selenium, amino acid complex* | Capsule Capsule |

| 9 | 200 | SeYeast | Capsule |

| 10 | 200 | SeYeast | Capsule |

| 11 | 20 | Selenium, amino acid chelate* | Capsule |

| 12 | 100 | SeMet | Softgel |

| 13 | 50 | SeYeast | Softgel |

Denotes selenium forms that were trademarked and/or proprietary.

2.3. Instrumentation

For selenium specific detection, an Agilent triple quadrupole ICP-MS model 8800 was used for all primary experiments. For secondary experiments, in which optimum instrument conditions were not as critical, an Agilent 7700x or 7500ce was used. All ICP-MS instruments utilized a Meinhard nebulizer and Peltier-cooled spray chamber (2 °C). Typical operating conditions included the following: RF Power = 1550 W, H2 reaction/collision gas flow 2 mL min−1, octopole bias = 9 V, and energy discrimination 2 V. The Agilent 8800 was operated in QQQ (MS/MS) mode using H2 as a reaction gas. The m/z 77Se, 78Se, 80Se, and 82Se were monitored in all experiments, with an integration time of 0.5 s for each with 78Se being the preferred isotope for reporting. Due to the relatively high concentrations of selenium in the supplements, ultra-low detection limits were not critical. Extensions of this method that require lower levels may apply the following modifications which have been shown to improve selenium sensitivity: ultrasonic nebulization (Goenaga Infante et al., 2004) and/or using N2 or CH4 as a reaction gas (Ni, Liu, & Qu, 2014; Olesik & Gray, 2014). As this method is intended to be routine, robust, and require little instrument modifications, these options were not explored.

An Agilent 1260 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) liquid chromatographic (LC) system with an autosampler, 6-port column switching valve (used as a post column switching valve for the selenium marker peak), binary pump (only one pump is required) was used with a Zorbax StableBond (SB-Aq) analytical column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm) from Agilent Technologies. For Separation 1, based on our previous work (Oliveira et al., 2016), the mobile phase was 25 mM ammonium acetate, 1 mM TBAH, pH 5.2, 2.5% (v/v) MeOH in DIW at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 using a 50 μL injection volume. (See SI-Table 1 for additional details). For all primary experiments, the aforementioned LC system was interfaced with the ICP-MS via a short piece of 0.007″ inner diameter polyether ether ketone tubing. Several secondary experiments with various instrument combinations were used to address specific areas of the method development and all pertinent operating conditions are listed in Supplemental information (SI)-Table 1.

For confirmation of synthesized selenium standards, including SeOMet, MeSeMet, MeSeOCys, and MSeA, a reversed phase separation was used and the flow from the LC column was split 1:1 between the ICP-MS and a Finnigan LTQ (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA, USA) electrospray ionization mass spectrometer (ESI-MS) using conditions for Separation 2, listed in SI-Table 1. This allowed for correlation of selenium containing peaks with molecular information. For initial analysis of the unknown selenium species associated with MeSeCys supplements, cation exchange chromatography with ICP-MS detection was used, details in SI-Table 1, Separation 3. For final confirmation of MeSeOCys and MSeA, exact mass data were obtained using a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive (ThermoFisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization source; the previously mentioned Separation 2 was used with no flow splitting. Electrospray conditions for the LTQ and Q Exactive are listed in SI-Table 2.

2.4. Total selenium analysis

The labeled liquid dosage, intact capsule, tablet, or softgel was weighed into a microwave digestion vessel with 8 mL of 15 M HNO3 and 1 mL of H2O2 and decomposed by microwave accelerated digestion using a MARSXpress (CEM, Matthew, NC, USA) with a heating program of a 25 min ramp to 200 °C and a 15 min hold time. Digested solutions were then diluted appropriately and analyzed for total selenium concentration using an ICP-MS under the conditions described above, but with a higher H2 gas flow rate, near 4.5 mL min−1. Rhodium was used as an internal standard by online mixing of the sample and internal standard solutions using the ICP-MS peristaltic pump with a mixing tee. Quality assurance procedures outlined in the FDA’s EAM 4.7 v1.1 were followed (Gray, Mindak, & Cheng, 2015). Selected samples were analyzed by a second lab using similar methodology, but with He as a collision gas. Results for total Se analysis performed by three analysts in two laboratories are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the label claim and the results obtained from the analysis of the selenium supplement samples using various analysis/extraction techniques. Label claim levels are based on the labeled amount per weight of the sample contents (excluding outer shells). The average concentration is reported in all cases; for Total Se and water extraction data a ±2σ is represented (n ≥ 3). For MSA and NaOH extractions which were used during method development, only 1-3 replicates were analyzed, therefore no standard deviations were reported. A dash (−) represents that a sample was not analyzed using the given conditions. A “nd” denotes that the analyte was not detected above LOD using the analysis conditions.

| Supplement # | Total Se (μg g−1) | Label Claim (μg Se g−1) |

Water Ext (μg Se g−1) |

4 M MSA Ext (μg Se g−1) |

0.1 M NaOH Ext (μg Se g−1) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeSeCys | SeMet | iSe | MeSeCys | SeMet | iSe | MeSeCys | SeMet | iSe | MeSeCys | SeMet | iSe | ||

| 1 | 38.7 ± 3.6 | – | – | 40 | nd | nd | 36.2 ± 3.5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 539 ± 97 | – | – | 450 | nd | nd | 600 ± 21 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 | 1074 ± 11 | – | 166 | 498 | nd | nd | 1140 ± 250 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | 615 ± 96 | – | 564 | – | nd | 658 ± 57 | nd | – | – | – | nd | 607 | 28* |

| 5 | 523 ± 84 | – | 473 | – | nd | 569 ± 75 | nd | nd | 384 | nd | – | – | – |

| 6 | 476 ± 52 | 451 | – | – | 504 ± 60 | nd | nd | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7 | 1524 ± 156 | 1552 | – | – | 1630 ± 100 | nd | nd | 1456 | nd | nd | – | – | – |

| 8 | 1112 ± 42 | – | 881† | – | nd | nd | 274 ± 27 | nd | nd | 35.5 | nd | nd | 913 |

| 9 | 549 ± 36 | – | 472† | – | nd | nd | 131 ± 7 | nd | nd | 25.9 | nd | nd | 408* |

| 10 | 624 ± 64 | – | 610† | – | nd | 34 ± 2 | nd | nd | 468 | nd | nd | nd | 33* |

| 11 | 19.8 ± 1.4 | – | 28‡ | – | nd | nd | nd | – | – | – | nd | nd | 0.9 |

| 12 | 49.8 ± 1.5 | – | 41 | – | nd | nd | nd | nd | 29.6 | nd | – | – | – |

| 13 | 110 ± 18 | – | 99† | – | nd | nd | 27 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Denotes Se as Se-yeast.

Denotes Se as selenium chelate (for simplicity, the SeMet column was chosen to represent both of Se-yeast and chelates).

Possible SeMet oxidation product, elutes near Se(IV).

2.5. Selenium speciation analysis

Samples were extracted with various solutions including water, 0.1 M NaOH, 1 M HCl, and 4 M MSA. Extractions were attempted with combinations of sonication and heating (room temperature, 50 °C and 95 °C) for various times using an ultrasonic bath (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT, USA) or a heating block (SCP Science, Montreal, Canada). Samples were then centrifuged (ThermoFisher Scientific) to draw particulates to the bottom, typically 10 min at 1700 g. LC-ICP-MS chromatograms of a selenium standard mix which was unfiltered, filtered with nylon, polytetrafluoroethylene, or polypropylene filters were compared with no significant differences in analyte recovery. Additionally, the relatively large dilution factor (~15,000) drastically reduces the probability of sample particulate (which could be deleterious to the analysis instrumentation) and dictated that sample filtration was not required for this method. Standards and samples were diluted in the mobile phase prior to analysis by LC-ICP-MS. All speciation standards were monitored for interconversion (using relative peak areas of LC-ICP-MS analysis of individual standards), specifically SeMet to SeOMet and Se(IV) to Se(VI) (and vice versa). Individual species concentrations of Se(IV) and Se(VI) are described for informational purposes, but due to Se(VI) to Se(IV) conversion in Se(VI) standard and possible oxidation/reduction in sample extractions, inorganic selenium (iSe) concentrations (sum of Se(IV) and Se (VI)) are reported. Impurities >2% of total 78Se peak area required adjustments to calculated concentrations of selenium standard mix. Quantitation of selenium species was carried out via external calibration from 2 to 100 ng Se g−1 using standard mixture of SeCys2, MeSeCys, SeMet, Se(IV), and Se(VI) prepared from ~10 μg Se g−1 stock standards. SeOMet and MeSeMet were not included in the calibration standards for routine analysis. The lack of a plant based selenium supplement precluded the use of MeSeMet, but it serendipitously represented the column void volume peak (peak 1, Fig. 1). Unknown selenium compounds and those for which stable standards were not available (including known oxidation/degradation products related to SeMet and MeSeCys) were quantitated based on the nearest eluting standard. To monitor ICP-MS sensitivity drift over the course of an analytical sequence, a post-column “marker” peak of a 50 μL solution of 5–10 ng g−1 Se(IV) in mobile phase was injected using a 6-port switching valve. All calibration curves had an r2 value of >0.99. Analytical solution detection limits (ASDL) were estimated by analyzing 10 replicates of a 0.4 ng g−1 Se mix standard to determine the concentration standard deviation (σ), then calculated using US FDA’s Elemental Analysis Manual, §3.2 (ASDL (~3.8σ) and ASQL (30σ)). The ASDL for each compound was 0.04–0.2 ng g−1, while the ASQL ranged 0.3–1.6 ng g−1. Dilution factors were typically 15,000 (for a sample weight of 0.5 g), which resulted in approximate limits of detection (LOD) ranging from 0.6 to 3 μg g−1 and limits of quantitation ranging from 4.5 to 24 μg g−1. The large dilution factor produced little to no matrix effects (i.e., retention time shifts, low chromatographic resolution) and could be adjusted if analysis of lower level species was desired. For MSA, HCl and NaOH extractions, dilutions factors <100 hindered chromatographic resolution, retention order, and analyte recovery of fortifications. Column recovery was determined by comparing the total Se concentration of the extract using flow injection analysis (LC-ICP-MS analysis with no analytical column) to the concentration sum of selenium compounds from speciation analysis of the same extract.

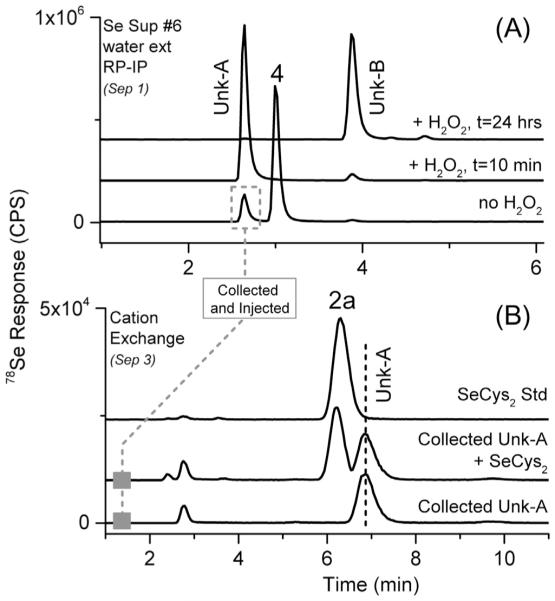

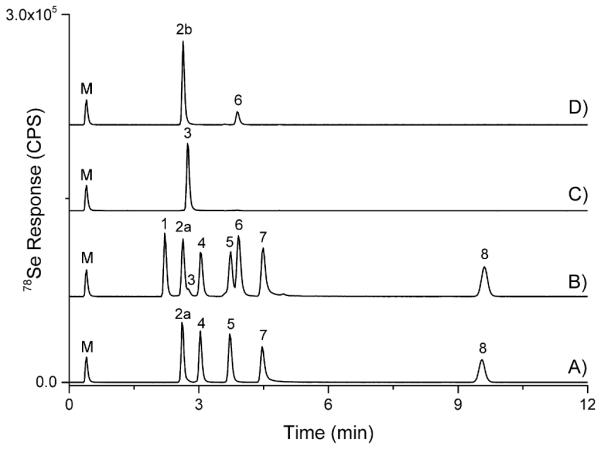

Fig. 1.

Standard LC-ICP-MS chromatograms using conditions for Separation 1 with a post-column selenium marker peak (M). A) ~10 ng Se g−1 selenium standard mixture in mobile phase including SeCys2 (2a), MeSeCys (4), SeMet (5), Se(IV) (7), and Se(VI) (8), B) ~10 ng Se g−1 selenium standard mixture in mobile phase with MeSeMet (1) and MSeA (6) standards added (note a SeOMet (3) impurity), C) ~10 ng Se g−1 SeOMet (3) in mobile phase, D) ~10 ng Se g−1 MeSeOCys (2b) in mobile phase, with the impurity MSeA (6).

3. Results & discussion

3.1. Total selenium determination

All dietary supplements analyzed in this study were labeled with the selenium amount in mcg (micrograms or μg) and the selenium species present. All samples were analyzed by ICP-MS at least in triplicate; each replicate represented one serving size. Selected samples #3, 5, 8, 11, and 12 were analyzed by a second laboratory to confirm the initial results. The results of the total Se analysis are summarized in Table 2. Sample #3 contained selenium at a concentration outside ±30% of the declared, at 162%. Supplement #11 contained 70% of the declared level. This trend is similar to a recent literature report in which Bakirdere et al. (2015) examined six Turkish pharmaceutical tablets and found one to be outside the ±30% of declared range, while Niedzielski et al. (2016) analyzed 86 supplements on the Polish market and found nonconformity in 48 samples (also ±30%). For quality assurance, SELM-1 was analyzed and the determined wet weight concentration of Se was 1820 mg Se kg−1 (1% RSD), which, when adjusted for a ~4% moisture content and compared to the revised certified value of total selenium of 2031 mg kg−1, yielded a 93% accuracy.

3.2. Selenium speciation determination, using water extraction

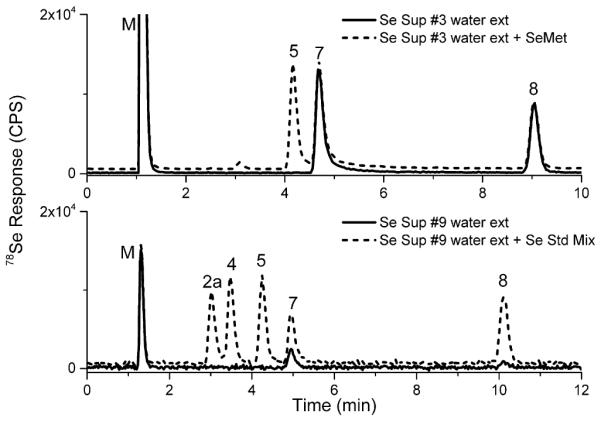

The concentrations of each species were determined and compared to the labeled concentrations, as well as the total Se concentration. Due to inherent issues preventing all inter-species conversions, SeMet concentrations were reported as the sum of SeMet and SeOMet, MeSeCys concentrations were reported as the sum of MeSeCys, MeSeOCys, and MSeA, while iSe concentrations were reported as the sum of Se(IV) and Se(VI). The final conditions for the water extraction were the addition of 10 g of water to the sample dosage amount (0.1–1.5 g), mixed thoroughly using a vortexer, and heated at 50 °C for 1 h. This resulted in a mass balance (sum of selenium species versus total Se) of 89–111% for samples #1–7, all of which were non-Se-yeast labeled supplements in the form of tablet, capsule, or liquid; this was in line with Bakirdere et al. (2015) who also deemed water extraction appropriate for tablets labeled as non-Se-yeast. Of these samples, only #3 contained selenium species not consistent with the label. Sample #3 was labeled to contain SeMet which was not detected (see Fig. 2, top portion). A summary of the speciation results from the water extracts and other attempted extractions are presented in Table 2. For selenium species within the calibration range, %RSD values (n ≥ 3) were <15%. Fortifications for each sample type (5 total samples selected) were prepared by adding a mixed standard of SeCys2, MeSeCys, SeMet, Se(IV), and Se(VI) at a concentration of ~50–100% of the total selenium concentration for each species. Fortification recoveries ranged from 73% to 120% for each species with an average of 105%. For samples #8–13, which included combinations of Se-yeast, selenium chelates, and softgels, mass balances were <40% (See Table 2). For various reasons explained subsequently, additional extractions were attempted, with emphasis on these hard to extract matrices.

Fig. 2.

Using chromatographic conditions for Separation 1, Se Supplement #3 (top) was examined and determined to not contain labeled SeMet (5). Se Supplement #9 (bottom) was determined to have increased iSe levels as compared to quality yeast (>2% of total Se).

3.3. Selenium speciation determination, Se-yeast samples, various extractions

As expected, (Casal, Far, Bierla, Ouerdane, & Szpunar, 2010) Seyeast supplements (#9, 10, 13) and SELM-1 subjected to water extraction yielded a low mass balance (Table 2). The major reason for first attempting the water extraction of the Se-yeast supplements was to extract iSe using the mildest extraction, thus minimizing the possibility of any Se-yeast components degrading to iSe. Therefore it was expected that the mass balance would be low for these supplement types. Although current Se-yeast regulations only rely upon iSe content, the possibility of obtaining iSe and organic selenium information would be desirable, therefore additional extractions were examined. While primarily intended for Se-yeast extraction/digestion, MSA has previously been shown to provide consistent results in regards to SeMet levels for SELM-1 (Mester et al., 2006) (comparable to enzymatic extractions); others have reported variability when applied to other commercial yeasts (Bierla et al., 2012). When applying the MSA extraction to samples #9 and 10, both labeled as Se-yeast, efficiencies were 5% (iSe) and 75% (SeMet), respectively. This low recovery could either be due to the inability to free the SeMet and/or iSe from the matrix or the presence of Se′ as concluded by (Barrientos et al., 2016). Although not commonly applied to Se-yeast samples, an alkaline extraction, 0.1 M NaOH was applied to two labeled as Se-yeast (#9 & 10). However, once additional peaks eluting at or near Se(IV), possibly related to SeMet oxidation products, were detected (LeBlanc, Ruzicka, & Wallschläger, 2015), this extraction method was deemed inappropriate for these sample types. This extra peak was not detected in water extracts and only appeared in the alkaline extraction samples analyzed >1 day after extraction.

The additional one-step extractions proved unsatisfactory for reasons explained above and enzymatic extractions were considered relatively cumbersome for routine use. Although the water extraction yielded a low mass balance, iSe, currently used to regulate Se-yeast quality in animal feeds, was extracted. The water extraction was applied to Se-yeast supplements #9, 10, and 13; the iSe contents were 24%, 0%, and 25% of the total selenium concentration, respectively. For #9 & #13, this is significantly above the regulations for animal feed. See the bottom portion of Fig. 2 for example chromatograms of #9. For Se-yeast sample #10, no iSe was detected using water, but extraction with MSA recovered 75% of the selenium as SeMet. While the iSe levels are the only criteria mentioned in the Code of Federal Regulations (Selenium, 2015), these results indicate that #9 & #13 likely contain low quality Se-yeast, while #10 likely contains Se-yeast of a higher quality. Caution should be taken when analyzing numerous water extracts of Se-yeast, as this may lead to column degradation from the large molecular weight, highly hydrophobic selenium species characteristic of Se-yeasts commonly being strongly retained on the column. This may be remedied by utilizing a guard column, column cleaning, and/or removing high molecular weight compounds via filtration prior to injection.

3.4. Selenium speciation determination, selenium amino acid chelates, various extractions

Due to the ambiguous label claim of selenium as an “amino acid chelate”, consumers could infer that seleno-amino acids (SeMet, MeSeCys, etc) were present in the supplement. This was discussed by Amoako, Uden, and Tyson (2009) who examined enzyme extractions of one purported “selenium amino acid chelate” and only detected iSe. Therefore other extractions were explored in an attempt to liberate any seleno-amino acids and/or iSe. An extraction using 0.1 M NaOH was applied to #8 and #11 with respective mass balances of 82% (iSe) and 5% (Se(IV)). Supplements labeled as selenium chelates claimed increased bioavailability. Therefore, in an attempt to mimic a more physiologically based approach, while possibly increasing extraction efficiency, an in vitro extraction previously used to assess arsenic bioaccesibility in rice was applied to chelated selenium supplements (details described in Ackerman et al. (2005); note: this is distinctly different than enzymatic extractions applied to Se-yeast by other researchers). However, extraction efficiencies for supplement #8, & #11 were similar to that of water extracts.

3.5. Selenium speciation determination, softgel selenium supplements, various extractions

To our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature regarding selenium speciation of softgel selenium supplements. Water extractions of the contents of softgel supplements #12 & #13 yielded mass balances of 0% and 25% (iSe), respectively. Therefore additional method protocols were utilized in an effort to extract the selenium species from the softgel contents. The extraction efficiency for #12 using 4 M MSA was 59% (SeMet). However, during fortification studies, the 4 M MSA extraction resulted in significant species interconversion (for organic Se species in particular) and low fortification recoveries. Low selenium recoveries using aqueous based extractions of the softgel were surmised to derive from the hydrophobic and immiscible nature of their contents. Therefore, the contents were dissolved with hexane and then extracted with water or 0.1 M HCl. The 0.1 M HCl increased extraction efficiency relatively by about 10% versus water alone and versus hexane/water for the Se-yeast supplement (#13), but there was no improvement for the SeMet supplement (#12). Due to little added benefit and a multi-step process, this extraction method was not utilized further.

Overall, the water extraction was comparable to other methods tested in regards to extracting selenium species that could be used to assess the presence and quantity of a labeled ingredient for non-Se-yeast supplements in tablet, capsule, and liquid forms. Also, the water extraction could be used to detect low quality Se-yeast supplements (with >2% iSe). For a select set of samples, the MSA (#10 & 12) or NaOH (#8 & 11) extractions provided improvements, but conditions are possibly too harsh, thus leading to transformation of the in situ species. A summary regarding the advantages/disadvantages of each extraction is presented in SI-Table 3.

3.6. Selenium speciation of seleno-amino acid oxidation products

When examining extracts containing MeSeCys or SeMet, additional peaks were frequently detected, with a dependence on analysis time after extraction. For SeMet supplements, the most common impurity was SeOMet, which has been reported in the literature for various sample types. The peak eluted near SeCys2 and baseline separation was not achieved (see Fig. 1, B & C) using the conditions for Separation 1 (resolution can be achieved with weaker eluent and longer analysis time). The presence of SeOMet was confirmed in selected samples by standard addition with a SeOMet standard and/or using Separation 2 with simultaneous ESI-MS and ICP-MS detection. Although SeCys2 and SeOMet are not well resolved, the high reproducibility of within batch retention times (tR) allows for relatively easy detection of SeOMet in samples.

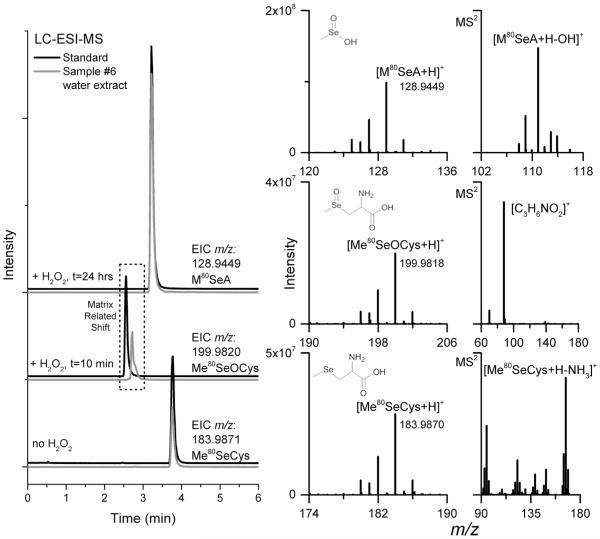

Impurities detected in the MeSeCys supplements were a little more complicated, as these supplements have not been widely examined in the literature, although Block et al. (2001) examined MeSeCys related compounds as pure standards and in onions. As storage time of the extracts increased, two additional peaks were detected: one with tR similar to SeCys2 (after 3–4 days storage) and another eluting near SeMet (after >7 days of storage). The addition of H2O2 to the extract (surmised to mimic extended storage time) resulted in similar degradation over a shorter time scale (demonstrated in Fig. 3-A). As previously mentioned, SeCys2 reports should be confirmed using multiple techniques when possible. Analyzing the water extract of #6 (labeled to contain MeSeCys) by cation exchange (see SI-Table 1, Separation 3 for conditions details), based on Smrkolj, Osvald, Osvald, and Stibilj (2007) proved problematic as the MeSeCys peak tail covered the SeCys2. Therefore, the SeCys2 peak (suspected, referred herein as Unk-A) from the #6 water extract was collected from repeated Separation 1 analyses and analyzed on cation exchange LC-ICP-MS (Fig. 3-B) and was determined to not be SeCys2 (nor SeOMet, as these peaks were resolved, data not shown). To confirm the peak identities, the extracts and H2O2 treatments were analyzed using LC with simultaneous ICP-MS and ESI-MS detection, by using retention time matching to find selenium isotope patterns and nominal masses. For further confirmation, the separation was transferred to a Q Exactive ESI-MS and analyzed (without ICP-MS detection) for exact mass and resultant fragmentation. The resulting chromatograms and spectra are shown in Fig. 4. Corresponding spectra represent the samples only, but were consistent with the standards. The peak Unk-A initially thought to be SeCys2, was determined to be Se-methylselenocysteine oxide (MeSeOCys), and the peak Unk-B was determined to be methylseleninic acid (MSeA). Although the MS2 of MeSeOCys does not provide much structural information, similar fragmentation was discussed in Anan et al. (2013). For MSeA, the MS2 spectra were consistent with the report by Gosetti et al. (2007). MeSeOCys is not commercially available and in our experience is stable for a matter of hours (less stable than SeOMet), making it difficult to obtain as a high purity standard. SeCys2 was not detected in any of the analyzed selenium supplements and elutes almost simultaneously with MeSeOCys using Separation 1 (Fig. 1). Therefore, SeCys2 was used as a substitute for MeSeOCys in the external calibration curves used for quantitation.

Fig. 3.

Chromatogram A used conditions for Separation 1; Chromatogram B used conditions for Separation 3. The Unk-A peak eluted similar to SeCys2 (2a) using the Separation 1 conditions.

Fig. 4.

LC-ESI-MS using a Q Exactive for detection, capable of exact mass determination; chromatographic conditions were for Separation 2. The theoretical m/z for the most abundant isotope (80Se) of each compound was used to generate each EIC trace (left). Full scan mass spectra (middle) display the measured m/z for the most abundant isotope; the measured m/z values for both samples and standards were all within 1.10 ppm of the theoretical m/z values. The spectra on the right contain the corresponding MS2 data.

3.7. Selenium speciation method performance characteristics

When using the methodology of Separation 1 with ICP-MS detection and the heated water extraction, the analyte retention times, within one analytical batch (~40 injections over >7 h), of the standards and fortified samples deviated 0–0.13 min (with Se (VI) showing the highest shift). A selenium standard mixture, injected 6 months apart (same components, fresh preparation) on the same column (>300 injections between), exhibited retention time shifts of less than 0.5 min while keeping similar resolution. Furthermore, the column was cleaned with 100% MeOH and then properly equilibrated for ~2 h, with a return comparable to the original performance. Additional method robustness testing included a small scale experiment in which a second analyst, using different models of Agilent LC and ICP-MS systems, and an LC column of a different lot number (using Separation 1), analyzed Se supplements #3 & #6. The results achieved were very similar and summarized in SI-Table 4.

4. Conclusions

A simple, efficient, and robust method has been presented to analyze select selenium-enriched dietary supplements for label verification. The water extraction, although not quantitative for Se-yeast, selenium chelates, or softgel supplements, is applicable for capsules, tablets and liquid form dosages labeled to contain selenite, selenate, selenomethionine, and/or Se-methylselenocysteine. Additionally, as current regulations permit, this method can assess Se-yeast quality based on iSe content; if future regulations are focused on organic selenium content (SeMet and others) of Se-yeast, then a more appropriate method would be that presented by Bierla and coworkers (Bierla et al., 2008).

The separation conditions are robust, reproducible, and isocratic, thus minimizing need for gradients, multiple column setup and other tedious parameters. The method can distinguish between MeSeMet (represents unretained Se species), MeSeOCys (represented by SeCys2), SeOMet, MeSeCys, SeMet, MSeA, Se(IV) and Se(VI). If analyzed within 24–48 h of extraction, little to no oxidation occurs, which limits peak overlap initially. This method can be used to analyze selenium-based dietary supplements to verify labeled components; this becomes increasingly important for sub-populations that need to closely control selenium intake.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.086.

References

- Ackerman AH, Creed PA, Parks AN, Fricke MW, Schwegel CA, Creed JT, Vela NP. Comparison of a chemical and enzymatic extraction of arsenic from rice and an assessment of the arsenic absorption from contaminated water by cooked rice. Environmental Science and Technology. 2005;39(14):5241–5246. doi: 10.1021/es048150n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoako PO, Uden PC, Tyson JF. Speciation of selenium dietary supplements; formation of S-(methylseleno)cysteine and other selenium compounds. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2009;652(1–2):315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anan Y, Yoshida M, Hasegawa S, Katai R, Tokumoto M, Ouerdane L, Ogra Y. Speciation and identification of tellurium-containing metabolites in garlic, Allium sativum. Metallomics. 2013;5(9):1215–1224. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00108c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaudguilhem C, Bierla K, Ouerdane L, Preud’homme H, Yiannikouris A, Lobinski R. Selenium metabolomics in yeast using complementary reversed-phase/hydrophilic ion interaction (HILIC) liquid chromatography–electrospray hybrid quadrupole trap/Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2012;757:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakirdere S, Volkan M, Ataman OY. Speciation of selenium in supplements by high performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Analytical Letters. 2015;48(9):1511–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos EY, Wrobel K, Guzman JCT, Escobosa ARC, Wrobel K. Determination of SeMet and Se (IV) in biofortified yeast by ion-pair reversed phase liquid chromatography-hydride generation-microwave induced nitrogen plasma atomic emission spectrometry (HPLC-HG-MP-AES) Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 2016;31(1):203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Bierla K, Dernovics M, Vacchina V, Szpunar J, Bertin G, Lobinski R. Determination of selenocysteine and selenomethionine in edible animal tissues by 2D size-exclusion reversed-phase HPLC-ICP MS following carbamidomethylation and proteolytic extraction. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2008;390(7):1789–1798. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1883-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierla K, Szpunar J, Yiannikouris A, Lobinski R. Comprehensive speciation of selenium in selenium-rich yeast. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2012;41:122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Block E, Birringer M, Jiang W, Nakahodo T, Thompson HJ, Toscano PJ, Zhu Z. Allium chemistry: Synthesis, natural occurrence, biological activity, and chemistry of Se-Alk(en)ylselenocysteines and their c-glutamyl derivatives and oxidation products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2001;49(1):458–470. doi: 10.1021/jf001097b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casal SG, Far J, Bierla K, Ouerdane L, Szpunar J. Study of the Se-containing metabolomes in Se-rich yeast by size-exclusion-cation-exchange HPLC with the parallel ICP MS and electrospray orbital ion trap detection. Metallomics. 2010;2(8):535–548. doi: 10.1039/c0mt00002g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheajesadagul P, Bianga J, Arnaudguilhem C, Lobinski R, Szpunar J. Large-scale speciation of selenium in rice proteins using ICP-MS assisted electrospray MS/MS proteomics. Metallomics. 2014;6(3):646–653. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00299c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LC, Combs GF, Jr., Turnbull BW, Slate EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, Taylor JR. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(24):1957–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernovics M, Lobinski R. Characterization of the selenocysteine-containing metabolome in selenium-rich yeast: Part II. On the reliability of the quantitative determination of selenocysteine. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 2008;23(5):744. [Google Scholar]

- DRI . Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium and Carotenoids. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2000. Selenium. [Google Scholar]

- Fairweather-Tait SJ, Collings R, Hurst R. Selenium bioavailability: Current knowledge and future research requirements. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;91(5S):1484S–1491S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28674J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenaga Infante H, O’Connor G, Rayman M, Wahlen R, Entwisle J, Norris P, Catterick T. Selenium speciation analysis of selenium-enriched supplements by HPLC with ultrasonic nebulization ICP-MS and electrospray MS/MS detection. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 2004;19(12):1529–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Gosetti F, Frascarolo P, Polati S, Medana C, Gianotti V, Palma P, Gennaro MC. Speciation of selenium in diet supplements by HPLC–MS/MS methods. Food Chemistry. 2007;105(4):1738–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Gray PJ, Mindak WR, Cheng J. Inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometric determination of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead, mercury, and other elements in food using microwave assisted digestion version 1.1. In Elemental analysis manual. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YJ, Jiang SJ. Determination of selenium compounds in food supplements using reversed-phase liquid chromatography–inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Microchemical Journal. 2013;110:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst R, Collings R, Harvey LJ, King M, Hooper L, Bouwman J, Fairweather-Tait SJ. EURRECA—estimating selenium requirements for deriving dietary reference values. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2013;53(10):1077–1096. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.742861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen EH, Hansen M, Fan T, Vahl M. Speciation of selenoamino acids, selenonium ions and inorganic selenium by ion exchange HPLC with mass spectrometric detection and its application to yeast and algae. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 2001;16(12):1403–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen EH, Hansen M, Paulin H, Moesgaard S, Reid M, Rayman M. Speciation and bioavailability of selenium in yeast-based intervention agents used in cancer chemoprevention studies. Journal of AOAC International. 2004;87(1):225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc K, Ruzicka J, Wallschläger D. Identification of trace levels of selenomethionine and related organic selenium species in high-ionic-strength waters. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-9124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mester Z, Willie S, Yang L, Sturgeon R, Caruso JA, Fernandez ML, Wolf W. Certification of a new selenized yeast reference material (SELM-1) for methionine, selenomethinone and total selenium content and its use in an intercomparison exercise for quantifying these analytes. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2006;385(1):168–180. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z, Liu Y, Qu M. Determination of 5 natural selenium species in selenium-enriched bamboo shoots using LC-ICP-MS. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2014;23(4):1049–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzielski P, Rudnicka M, Wachelka M, Kozak L, Rzany M, Wozniak M, Kaskow Z. Selenium species in selenium fortified dietary supplements. Food Chemistry. 2016;190:454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.05.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesik JW, Gray PJ. Advantages of N2 and Ar as reaction gases for measurement of multiple Se isotopes using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry with a collision/reaction cell. Spectrochimica Acta, Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy. 2014;100:197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AF, Landero J, Kubachka K, Nogueira ARA, Zanetti MA, Caruso J. Development and application of a selenium speciation method in cattle feed and beef samples using HPLC-ICP-MS: Evaluating the selenium metabolic process in cattle. Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry. 2016;31(4):1034–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsent J. Need for selenite and molybdate in the formation of formic dehydrogenase by members of the Escherichia coli-Aerobacter aerogenes group of bacteria. Biochemistry Journal. 1954;57:10–16. doi: 10.1042/bj0570010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayman MP. The use of high-selenium yeast to raise selenium status: How does it measure up? British Journal of Nutrition. 2004;92(04):557–573. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayman MP. Food-chain selenium and human health: Emphasis on intake. British Journal of Nutrition. 2008;100(2):254–268. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508939830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayman M. Selenium and cancer prevention. Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice. 2012;10(Suppl. 4):A1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selenium 21 CFR 573. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Smrkolj P, Osvald M, Osvald J, Stibilj V. Selenium uptake and species distribution in selenium-enriched bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) seeds obtained by two different cultivations. European Food Research and Technology. 2007;225(2):233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Stadlover M, Sager M, Irgolic K. Identification and quantification of selenium compounds in sodium selenite supplemented feeds by hplc-icp-ms. Die Bodenkultur. 2001;52(4):233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwary AK, Stegelmeier BL, Panter KE, James LF, Hall JO. Comparative toxicosis of sodium selenite and selenomethionine in lambs. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2006;18(1):61–70. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinceti M, Dennert G, Crespi CM, Zwahlen M, Brinkman M, Zeegers MPA, Del Giovane C. Selenium for preventing cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;2014;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005195.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel K, Wrobel K, Kannamkumarath SS, Caruso JA. Identification of selenium species in urine by ion-pairing HPLC-ICP-MS using laboratory-synthesized standards. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2003;377(4):670–674. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2147-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuilloud RG, Berton P. Selenium speciation in the environment. CRC Press; 2014. pp. 263–305. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.