Promoting transparency in scientific authorship

Transparency in scientific authorship. Image courtesy of iStock.com/exdez.

Conventions for listing authors in scientific publications vary between disciplines, cultures, and research groups. As a result, determining the extent to which an author may have contributed to or is accountable for a given publication is challenging. Marcia McNutt et al. (pp. 2557–2560) propose policies for scientific journals that are designed to clarify authors’ responsibilities. The authors encourage journals to adopt a uniform standard for what qualifies individuals to be authors in scientific articles. Requiring corresponding authors to disclose the use of editorial or technical writing services and to justify changes to the author list would discourage certain detrimental authorship practices. Adopting and embedding the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT) and ORCID digital identifiers into article metadata would make individual authors’ contributions explicit, searchable, and quantifiable. The development, dissemination, and regular review of authorship policies by research institutions would establish a framework for assigning authorship before research is undertaken. Finally, the authors encourage funding agencies to require the use of ORCID iDs and CRediT by their researchers, and scientific societies to consider the proposed policies at meetings and to implement the policies in publishing programs. — B.D.

HIV-associated bone loss points to putative viral reservoir

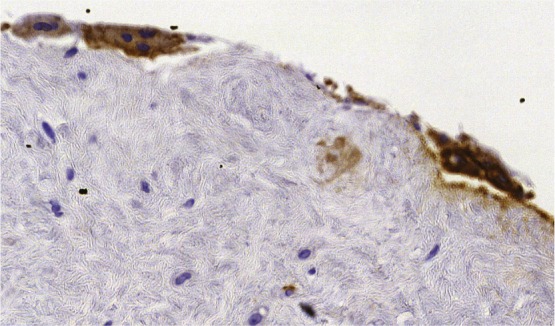

HIV-infected osteocytes in human synovial tissue.

By some estimates, HIV-infected people are at sixfold heightened risk of bone mineral loss, compared with uninfected people. Antiretroviral drugs are tied to bone loss, but HIV can itself weaken bone by altering the balance between bone formation and resorption. Brigitte Raynaud-Messina et al. (pp. E2556–E2565) tested whether HIV-1 directly targets osteoclasts, cells that secrete bone matrix-resorbing enzymes in a specialized scaffold called the sealing zone. The authors detected infected osteoclasts in femurs and tibias from HIV-1–infected mice and in cultures of human synovial joint membranes exposed to HIV-1. In laboratory dishes, the virus either directly infected osteoclasts or passed from infected T helper cells, the main target, to osteoclasts through direct contact between the cells. Further, HIV-1 was found to replicate within osteoclasts with no cytotoxic effects, enhance the migration and adhesion of osteoclast precursors to bone, and increase the volume of resorbed bone. Enhanced bone resorption by osteoclasts mirrored enhanced activity of the Src enzyme, which helps form and stabilize sealing zones. The viral protein Nef, known to activate Src, boosted the activity of osteoclasts in vivo, potentially accelerating bone loss. According to the authors, osteoclasts represent little-explored targets of HIV-1 and may serve as putative viral reservoirs shielded from the reach of therapeutic drugs. — P.N.

Genomic survey of elephants reveals recurring genetic admixture

Swazi, the African savanna elephant in San Diego Zoo whose reference genome was sequenced, is at left. Image courtesy of San Diego Zoo Global.

The evolutionary history of elephants remains largely undeciphered. Eleftheria Palkopoulou et al. (pp. E2566–E2574) sequenced 14 genomes from living and extinct elephant family members, including a high-quality reference sequence for the African savanna elephant, a 120,000-year-old straight-tusked elephant, and the Columbian mammoth, as well as the extinct American mastodon. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that African savanna elephants are a distinct species from African forest elephants, with little evidence of recent genetic exchange. Though hybridization between savanna and forest elephants occurs in regions of range overlap and results in fertile offspring, the species appear to have diverged around 5–2 million years ago, and their ancestors remained largely isolated for the past 500,000 years, reinforcing their distinct identities and the need for separate conservation measures. The genomes of Columbian and North American woolly mammoths revealed signs of admixture, bolstering previous accounts of interbreeding that were based on mitochondrial DNA analysis. Contrary to previous accounts, straight-tusked elephants were found to be of tripartite descent: from a lineage that gave rise to forest and savanna elephants, a lineage related to woolly mammoths, and a lineage related to living forest elephants. Analysis of the American mastodon genome revealed that mastodons diverged from elephant family members around 28–10 million years ago. In contrast to previous accounts of an evolutionary history marked by a series of diverging populations, the study uncovers signs of genetic commingling among elephant family members, replete with recurring periods of isolation and interbreeding. — P.N.

Mouse model of genetic emphysema

The leading genetic cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, which is characterized by mutations in the SERPINA1 gene. The presence of multiple paralogs of Serpina1 in mice has hampered efforts to create a mouse model that could aid drug development. Florie Borel et al. (pp. 2788–2793) used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing to knock out five Serpina1 genes in mice, creating a mouse model of genetic emphysema. The authors report that the resulting genetically modified mice had a normal lifespan and recapitulated many aspects of the human disease. AAT protects lungs by inactivating the neutrophil elastase enzyme, and the authors found that the lack of hepatic and circulating AAT in Serpina1 knockout mice results in reduced capacity to inhibit neutrophil elastase. Exposing mouse airways to a mild lipopolysaccharide challenge resulted in phenotypes similar to those of patients with emphysema. In addition, the Serpina1 knockout mice spontaneously developed emphysema with age. Serpina1 knockout mice could serve as a genetic model for the preclinical development of therapeutics against AAT deficiency lung disease and help illuminate the biology of emphysema, according to the authors. — S.R.

Ants weigh risk to self during sanitary care of group members

Garden ant workers. Image courtesy of Sina Metzler and Roland Ferrigato (Institute of Science and Technology Austria, Klosterneuburg, Austria).

Ants and termites perform group sanitary care through physical grooming or chemical disinfection of pathogens found on the bodies of contaminated group members. Contamination during sanitary care can lead to low-level infection of caregivers, resulting in heightened future immunity to the same pathogen but increased susceptibility to other pathogens. Matthias Konrad et al. (pp. 2782–2787) tested whether caregiving invasive garden ants (Lasius neglectus) adjusted sanitary care according to the risk of contracting an infection. When garden ant workers were reared with a nestmate contaminated with either of two fungi—Metarhizium robertsii or Beauveria bassiana—subsequent challenge of caregivers with the same or different fungus revealed a protective or predisposing effect, respectively. Further, caregivers adjusted sanitary care according to their own infection: When infected with a different pathogen compared with nestmates, caregivers favored the less contact-intensive strategy of disinfection, in which ants spray antimicrobial poison on contaminated nestmates, over grooming, in which ants use their mouthparts to remove infectious particles from nestmates’ cuticles. The latter finding suggests that ants provide risk-adjusted sanitary care. Importantly, such risk adjustment resulted in reduced risk of subsequent infection with the harmful pathogen. According to the authors, uncovering the influence of immunity on behavior might help protect agriculturally important social insects, such as pollinators. — P.N.