Significance

Social insects provide sanitary care to colony members that are contaminated with infectious disease particles. Although this reduces the risk of contaminated individuals falling sick, the caregiving individuals risk pathogen contraction themselves. Small pathogen doses can lead to low-level infections that do not cause disease but make individuals more susceptible to secondary infection (superinfection) with a different pathogen. Here, we reveal the remarkable capacity of ants to react to this increased disease susceptibility by altering their sanitary care performance. Low-level–infected ants reduced grooming and applied more of their antimicrobial poison onto nestmates contaminated with a harmful second pathogen, thereby reducing their own risk of superinfection during caregiving. This risk-averse health care will likely improve and maintain overall colony health.

Keywords: host–pathogen interactions, social immunity, behavioral plasticity

Abstract

Being cared for when sick is a benefit of sociality that can reduce disease and improve survival of group members. However, individuals providing care risk contracting infectious diseases themselves. If they contract a low pathogen dose, they may develop low-level infections that do not cause disease but still affect host immunity by either decreasing or increasing the host’s vulnerability to subsequent infections. Caring for contagious individuals can thus significantly alter the future disease susceptibility of caregivers. Using ants and their fungal pathogens as a model system, we tested if the altered disease susceptibility of experienced caregivers, in turn, affects their expression of sanitary care behavior. We found that low-level infections contracted during sanitary care had protective or neutral effects on secondary exposure to the same (homologous) pathogen but consistently caused high mortality on superinfection with a different (heterologous) pathogen. In response to this risk, the ants selectively adjusted the expression of their sanitary care. Specifically, the ants performed less grooming and more antimicrobial disinfection when caring for nestmates contaminated with heterologous pathogens compared with homologous ones. By modulating the components of sanitary care in this way the ants acquired less infectious particles of the heterologous pathogens, resulting in reduced superinfection. The performance of risk-adjusted sanitary care reveals the remarkable capacity of ants to react to changes in their disease susceptibility, according to their own infection history and to flexibly adjust collective care to individual risk.

The infection history of a host can severely impact its future disease susceptibility. For example, previous infections or vaccinations can immunize and thus protect hosts against secondary infections of the same, homologous pathogen, a phenomenon known as “immune memory” in vertebrates and “immune priming” in invertebrates (1, 2). However, prior infection can also increase a host’s susceptibility to other, heterologous pathogens, particularly if the second infection occurs when the first has not yet been cleared from the host’s body. Superimposed secondary infections, known as “superinfections,” often have greater detrimental impacts on host health and survival induced by competition or cooperation between the two pathogens within the host (e.g., causing more rapid host exploitation than either pathogen alone) (3, 4). In addition to an immune response, host behavior often also changes upon infection: On the one hand, pathogens can manipulate host behavior to facilitate disease transmission (5); on the other, changes in host responses—termed sickness behavior—can speed up recovery and limit pathogen spread (e.g., through reduced activity and modulation of social interactions) (6, 7). Infection can even alter an animal’s sensitivity to pathogen-associated stimuli, as, for example, disease avoidance behavior (8) can be affected by a host’s infection history (9, 10).

Disease prevention is particularly important in social groups, where pathogens can easily spread due to a high density of hosts and the multitude of interactions between them (11, 12). Consequently, social animals have evolved behavioral disease defenses, which operate in conjunction with individual immunity, to negate the increased pathogen risk they experience (13, 14). For example, social insects have evolved sophisticated, collective defenses against diseases that result in an emergent, group-level protection of the colony, known as social immunity (14, 15). One particularly important component of social immunity is sanitary care—grooming to remove pathogens (16, 17) and chemical disinfection to inhibit their growth (18, 19)—that effectively reduces the risk of disease for pathogen-exposed individuals. However, this intimate behavioral interaction often also involves pathogen transmission from the contaminated individual to those performing sanitary care. Insects caring for their nestmates can therefore either become sick themselves (16, 17) or contract low-level infections that do not lead to disease symptoms but instead confer protection against the same, homologous pathogen upon secondary exposure. For example, in both ants (20) and termites (21) social contact with contaminated individuals carrying infectious conidiospores of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium on their cuticle causes low-level infections in most of their nestmates, with very little variation in infection level (20). Interestingly, these low-level infections trigger an up-regulation of antifungal genes, and hence antifungal activity of the insects (20, 21), which leads to a significant survival benefit—known as social immunization (2)—upon secondary challenge with the same, homologous pathogen (22, 23). In humans, prior natural infections and vaccination affect individual pathogen avoidance behavior (10) and strategies for providing health care (24, 25). However, in social insects, it is unknown how the infection state of a host affects its future susceptibility to different (heterologous) pathogens and whether low-level infections can alter the performance of sanitary care of ants.

To address this, we set up a full-factorial experiment, using a natural host–pathogen system of garden ants and entomopathogenic fungi (hosts: Lasius ants; pathogens: Metarhizium and Beauveria fungi) (26, 27). These two pathogens have similar reproductive cycles: Infectious conidiospores are acquired from the environment/infectious corpses and initially attach loosely to an insect’s cuticle (28). During this stage, conidiospores can be removed from contaminated ants through grooming (17, 29), or inactivated by disinfection to prevent infection (18, 19), and can also be transferred from contaminated individuals to those performing sanitary care (20). However, once the conidiospores fully adhere to the cuticle they can no longer be removed (30) and will penetrate into the hemocoel of the insect, causing an internal infection (28). If the infective dose is high enough to overcome the immune system the fungus will kill the host and grow out of the body, eventually producing new conidiospores on the corpse (17, 28).

To elucidate the effects of low-level infections acquired through sanitary care on the future disease susceptibility and sanitary care of ants, we induced low-level infections in individuals by rearing Lasius neglectus workers with a pathogen-exposed nestmate, treated with conidiospores of either Metarhizium robertsii or Beauveria bassiana, for 5 d (as in ref. 20), while noninfected control ants were reared with a sham-treated individual which could not transfer any pathogen. We then tested how acquired low-level infections (i) affect ant mortality upon a challenge with the same or heterologous pathogen, (ii) whether low-level infections change the expression of sanitary care toward contaminated nestmates, and (iii) if this alters disease transmission dynamics.

Results and Discussion

Low-Level Infections Increase an Ant’s Susceptibility to Heterologous Superinfection.

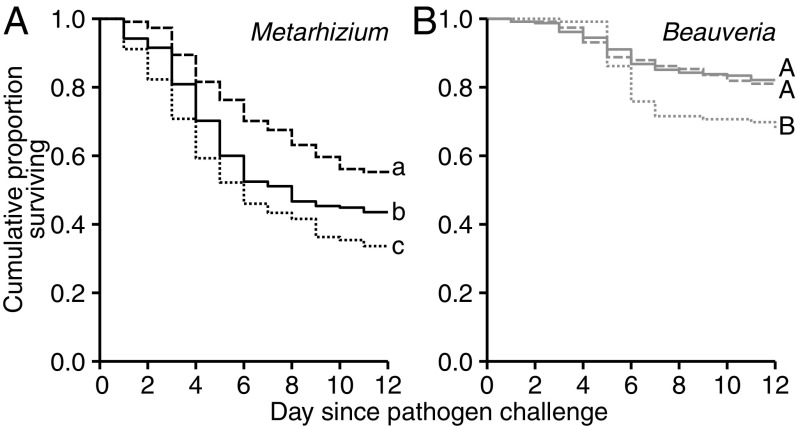

We established low-level infections of either Metarhizium or Beauveria in L. neglectus ants (Fig. S1) and compared how they affected ant survival after a challenge with either a homologous (Metarhizium–Metarhizium or Beauveria–Beauveria) or a heterologous (Metarhizium–Beauveria or Beauveria–Metarhizium) pathogen. Control ants had no previous infection (noninfected–Metarhizium and noninfected–Beauveria). Overall, we found that a challenge with Metarhizium (Fig. 1A) had a significantly stronger effect on ant survival than a Beauveria challenge (Fig. 1B), indicating that Metarhizium is more virulent to L. neglectus ants [Cox mixed-effects model (COXME): overall likelihood ratio test (LR) χ2 = 122.36, df = 4, P < 0.0001; pathogen challenge: χ2 = 10.18, df = 1, P = 0.0014]. As in a previous study of social immunization in garden ants using a different Metarhizium species (20), we found a protective effect of a low-level M. robertsii infection when ants were challenged with the homologous pathogen [Fig. 1A; COXME: infection state LR χ2 = 13.81, df = 2, P = 0.002; post hoc comparisons: noninfected vs. homologous, P = 0.033, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.69]. Hence, social immunization can be elicited by multiple Metarhizium species. However, there was no protective effect of homologous low-level infections of Beauveria (Fig. 1B; COXME: infection state LR χ2 = 8.38, df = 2, P = 0.015; post hoc comparisons: noninfected vs. homologous, P = 0.81, HR = 1.07), despite both pathogens having established low-level infections at equal intensity (Fig. S1). This indicates that social immunization is induced by some, but not all, pathogens, similar to pathogen-specific individual and transgenerational immune priming in invertebrates (reviewed in ref. 2). Here, we speculate that Beauveria—being a less-virulent pathogen of L. neglectus ants (Fig. 1 and Fig. S2)—may elicit a weaker immune reaction in the ants compared with the more-virulent Metarhizium. Since social immunization involves increased expression of immune genes during the first infection (20), less-virulent pathogens may not stimulate the immune system strongly enough to trigger successful immunization, a hypothesis we consider worthwhile to test in future work, using pathogens of varying virulence.

Fig. 1.

Increased mortality of low-level–infected ants after heterologous pathogen challenge. Mortality of L. neglectus ants was, overall, higher after a challenge with Metarhizium (A; black lines) than Beauveria (B; gray lines). For both pathogens, ant mortality after challenge was affected by the infection state of the individuals, which was either no prior infection (solid lines) or a low-level infection of a pathogen homologous (dashed lines) or heterologous to the pathogen they were challenged with (dotted lines). Homologous low-level infections resulted in protective immunization for Metarhizium but not Beauveria. Heterologous low-level infection, in contrast, consistently increased ant mortality in both pathogen challenges. Different letters indicate groups that differ significantly in post hoc comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple testing at α = 0.05. Sample size n = 919 ants. Supporting data are given in Dataset S2.

A heterologous challenge (Metarhizium–Beauveria or Beauveria–Metarhizium), in contrast, invariably increased ant mortality, both compared with the noninfected controls (noninfected vs. heterologous: non-Metarhizium vs. Beauveria–Metarhizium: P = 0.047, HR = 1.34; non-Beauveria vs. Metarhizium–Beauveria: P = 0.014, HR = 1.89) and the homologous challenge (homologous vs. heterologous: Metarhizium–Metarhizium vs. Beauveria–Metarhizium: P = 0.0007, HR = 1.95; Beauveria–Beauveria vs. Metarhizium–Beauveria: P = 0.0498, HR = 1.77). To test if this effect was dependent on whether one of the two pathogens had already established an infection in the host body, or if it reflects a general pattern of Metarhizium–Beauveria coinfection, we simultaneously coexposed ants to a mix of both pathogens, keeping the overall pathogen dose constant. Again, we found a strong mortality-inducing effect of coexposure compared with ants exposed to only the single pathogens (Fig. S2). Similar harmful effects are well established for heterologous challenges after individual and transgenerational immune priming (2, 31, 32) and concurrent infections with different pathogens (3, 4). They can result either from pathogen–pathogen interactions, including both competition and cooperation (33, 34), or from perturbations of the host immune system (35, 36).

Ants with Low-Level Infections Modulate Their Sanitary Care.

Social insect colonies face a high load (37) and diversity (38) of pathogens in their environment, making multiple infections of individual colony members likely. Given the observed costs of increased susceptibility to heterologous pathogens after a previous, otherwise asymptomatic low-level infection, we expect selection to act on ants to avoid superinfection with detrimental heterologous pathogens. As contaminated individuals represent a constant risk of infection for their colony members (16, 17, 20), we tested the hypothesis that ants should modulate their behavior to selectively reduce the risk of heterologous pathogen contraction when in contact with a pathogen-contaminated nestmate. To this end, we confronted low-level–infected ants with a contaminated nestmate, from which they could contract a superinfection of either the homologous or heterologous pathogen, and observed how their behavior differed from that of noninfected ants (Movie S1).

While aggression between nestmates is usually absent in L. neglectus colonies (39), infected ants started biting, grabbing, and dragging their contaminated nestmates. This effect was independent of whether the nestmate was contaminated with Metarhizium or Beauveria [Fig. 2A; generalized linear model (GLM) overall: LR χ2 = 13.40, df = 3, P = 0.004; nestmate contamination: LR χ2 = 0.02, df = 1, P = 0.90]. Moreover, aggression was increased in all ants with low-level infections compared with the noninfected controls, irrespective of whether the nestmate was contaminated with a pathogen homologous or heterologous to their low-level infection (infection state: LR χ2 = 12.35, df = 2, P = 0.002; post hoc comparisons: noninfected vs. homologous, P = 0.008; noninfected vs. heterologous, P = 0.0002; homologous vs. heterologous, P = 0.24). Hence, while increased aggression has previously been reported for infected ants toward nonnestmates from different colonies (40), and by healthy ants and honey bees toward infected or immune-challenged nestmates (41–43), here we find that low-level–infected ants have a heightened level of aggression themselves toward their own colony members.

Fig. 2.

Modulation of behavior displayed by low-level–infected ants toward contaminated nestmates. (A) Aggression, (B) allogrooming, and (C) poison spraying were performed equally toward nestmates contaminated with Metarhizium (black) or Beauveria (gray) but depended on the ants’ infection state, which was either no prior infection or a low-level infection of a pathogen homologous or heterologous to the pathogen the nestmate was contaminated with. (A) The aggression level of low-level–infected ants was higher compared with noninfected controls but did not differ when the nestmate was contaminated with the homologous or heterologous pathogen. (B) Grooming was performed significantly longer by low-level–infected ants to a nestmate contaminated with the homologous pathogen, compared with both noninfected control ants and low-level–infected ants grooming nestmates contaminated with heterologous pathogen. (C) Poison spraying was essentially absent in noninfected control ants but increased in low-level–infected ants interacting with a nestmate contaminated with the homologous pathogen and was increased further when the nestmate was contaminated with the heterologous pathogen. Mean ± SEM displayed separately for Metarhizium and Beauveria, with the line indicating a nonsignificant difference between the two pathogens; different letters indicate groups that differ significantly in post hoc comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple testing at α = 0.05. Sample size n = 720 ants in 144 independent replicates. For the number of ants engaging in the particular behaviors see Fig. S3. Supporting data are given in Dataset S3. For the behavior toward noncontaminated control nestmates see Fig. S4 and Dataset S4.

Despite increased aggression, infected ants still performed sanitary care—grooming and chemical disinfection (18)—toward their contaminated nestmates. When grooming, ants remove infectious particles with their mouthparts from the cuticle of nestmates (17, 29, 44). In addition, L. neglectus ants spray their formic acid-rich, antimicrobial poison onto exposed colony members—an effective disinfection behavior that is distinct from defensive poison use (18). The application process itself is a fast and infrequent behavior, followed by a long replenishment phase of the poison reservoir (18). We found that the relative expression of allogrooming and poison spraying in ants was dependent on whether nestmates were contaminated with a pathogen that was homologous or heterologous to their low-level infection (Fig. 2 B and C).

Allogrooming duration did not differ toward nestmates contaminated with either Metarhizium or Beauveria (Fig. 2B; GLM, overall: F = 6.78, df = 3, P = 0.0003; nestmate contamination: F = 0.65, df = 1, P = 0.42). However, as observed in other species (30), prior pathogen encounter caused an increase in the grooming of nestmates contaminated with a homologous pathogen (infection state: F = 9.85, df = 2, P = 0.0001; post hoc comparisons: noninfected vs. homologous, P = 0.0004). Importantly, however, grooming did not increase when ants encountered nestmates contaminated with a heterologous pathogen (noninfected vs. heterologous, P = 0.86) and was hence only significantly more frequent in interactions with nestmates carrying the homologous pathogen (homologous vs. heterologous, P = 0.0004).

Poison spraying did not differ toward Metarhizium- or Beauveria-contaminated individuals (Fig. 2C; GLM, overall: LR χ2 = 22.85, df = 3, P = 0.00004; nestmate contamination: LR χ2 = 0.97, df = 1, P = 0.32). While this behavior was essentially absent in noninfected ants, those with low-level infections regularly performed spraying. However, interestingly, ants sprayed poison significantly more often toward nestmates when they carried a low-level infection of the heterologous rather than the homologous pathogen (infection state: LR = 22.27, df = 2, P = 0.00001; post hoc comparisons: noninfected vs. homologous, P = 0.02; noninfected vs. heterologous, P = 0.002; homologous vs. heterologous, P = 0.02).

Overall, our data show that low-level–infected ants become aggressive toward their contaminated nestmates but nevertheless still perform sanitary care. However, they modulate the components of sanitary care, in that infected ants perform relatively more poison spraying but less grooming of nestmates contaminated with a heterologous compared with the homologous pathogen. Furthermore, we found that when these behaviors occur all three are performed by equal numbers of ants across treatments (Fig. S3).

To test whether the behavioral changes displayed by infected ants are specific to encounters with pathogen-contaminated individuals, we observed the behavior of Metarhizium-, Beauveria-, or noninfected ants toward a noncontaminated, sham-treated nestmate. We found that low-level–infected ants were also more aggressive to noncontaminated nestmates and groomed them for longer than noninfected controls, similar to ref. 44 (Fig. S4). However, poison spraying was essentially absent, occurring only in two instances. This demonstrates that low-level infections per se increase levels of aggression and allogrooming but that specific risk-averse sanitary care—reduced allogrooming and elevated poison spraying—is expressed uniquely during interactions with nestmates where low-level–infected ants may contract a detrimental, heterologous pathogen. Next, we set out to determine how this behavioral modulation affects pathogen transmission dynamics during sanitary care and whether it reduces the risk of low-level–infected ants’ developing harmful superinfections.

Risk-Adjusted Sanitary Care Reduces Heterologous Pathogen Transfer and Superinfection.

To simultaneously measure pathogen transmission and fungal growth inhibition via antimicrobial poison spraying we quantified the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) of viable infectious fungal conidiospores transferred to the body surface of ants performing sanitary care, immediately after social interaction with contaminated nestmates. We found that ants acquired significantly more infectious conidiospores when their nestmate was contaminated with Metarhizium rather than Beauveria (Fig. 3A; GLM, overall: F = 8.86, df = 3, P = 0.00002; nestmate contamination: F = 8.11, df = 1, P = 0.005). However, independent of pathogen species, infected ants acquired significantly less infectious particles from contaminated nestmates when they had a heterologous low-level infection, compared with both homologous infected ants and noninfected controls (Fig. 3A; Metarhizium: infection state: GLM, F = 5.54, df = 2, P = 0.012; Beauveria: infection state: GLM, F = 3.95, df = 2, P = 0.024; post hoc comparisons for both pathogens: noninfected vs. homologous, P > 0.7; noninfected vs. heterologous, P < 0.032; homologous vs. heterologous, P < 0.05). These data reveal that the behavioral plasticity displayed by the ants, which is dependent on the combination of their infection state and current risk of pathogen contraction, resulted in a reduced transfer of the harmful heterologous, but not the nondetrimental, homologous pathogen compared with noninfected control ants.

Fig. 3.

Reduced heterologous pathogen transfer to and superinfection of low-level–infected ants. (A) Low-level–infected ants acquired viable, infectious pathogen from their contaminated nestmates. Overall, higher pathogen transfer occurred when the nestmate was contaminated with Metarhizium (black) rather than Beauveria (gray). For both pathogens transfer depended on the infection state of the ants. While ants with a homologous low-level infection acquired equal amounts of the pathogen than noninfected controls, ants with heterologous low-level infections acquired less pathogen than both the noninfected control and ants with homologous infections. (B) Superinfection load of both pathogens was reduced in ants displaying risk-averse behavioral modulation compared with control ants. Mean ± SEM displayed; different letters indicate significance groups of all pairwise post hoc comparisons after Benjamini–Hochberg correction at α = 0.05. Sample size: (A) n = 820 ants in 164 independent replicates and (B) n = 255 ants in 51 independent replicates. Supporting data are given in Dataset S5.

Since exposure dose is related to infection load and the subsequent risk of disease in fungal pathogen–ant host systems (45), we tested whether the reduced transfer of the harmful heterologous pathogen translates into a lower superinfection load in low-level–infected ants. To this end, we exposed low-level–infected ants to two different doses of their heterologous pathogens: (i) a low dose equivalent to the amount ants received when performing risk-adjusted sanitary care (determined from data in Fig. 3A; heterologous pathogen combinations) or (ii) a higher dose equivalent to the amount received when the behavioral change was absent (determined from data in Fig. 3A; noninfected control ants). We found that the reduced transfer of infectious conidiospores in ants displaying risk-adjusted sanitary care does indeed affect their risk of developing a superinfection and its load within the ants. The risk of contracting a superinfection was reduced for Metarhizium, from 100% (95% CI = 0.77–1.0) in the controls to 85% (CI = 0.58–0.96), and we were unable to detect any superinfections of Beauveria (0%; CI = 0.00–0.23) compared with 92% (CI = 0.67–0.99) in the controls. Quantification of the internal superinfection load of all ants revealed a significant decrease in superinfection severity for both pathogens (Fig. 3B; Metarhizium: LR χ2 = 20.45, df = 1, P < 0.0001: Beauveria: LR χ2 = 42.34, df = 1, P < 0.0001). A reduced superinfection load will benefit the host because the degree of harm caused by these fungal pathogens is dose-dependent (45). We can therefore conclude that the risk-adjusted sanitary care displayed by low-level–infected ants will reduce their chances of acquiring the harmful, heterologous pathogen and, subsequently, the ants’ risk of developing a detrimental superinfection.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated how low-level infections acquired through sanitary care affect an ant’s disease susceptibility to future infections with the same, homologous or different, heterologous pathogen and, as a consequence, how this affects their interactions with pathogen-contaminated nestmates. We found that low-level infections had a protective or neutral effect when ants were exposed to the homologous pathogen but consistently increased an ant’s susceptibility to superinfection when ants were challenged with heterologous pathogens (Fig. 1). However, by altering the relative expression of grooming and poison spraying (Fig. 2) low-level–infected ants were able to specifically reduce the amount of heterologous pathogens they acquire when performing sanitary care of contaminated nestmates (Fig. 3A). Importantly, this risk-averse behavior resulted in both a lower probability of developing a superinfection with the detrimental heterologous pathogen and a reduced superinfection load (Fig. 3B).

While heterologous superinfection avoidance behavior was consistent, we found specific effects of Metarhizium and Beauveria on survival and pathogen transfer. Namely, Metarhizium caused higher mortality in L. neglectus ants than Beauveria, and only homologous low-level infections of this more virulent pathogen led to protective social immunization (Fig. 1). Despite both pathogens’ being present in equal amounts on the nestmates, care-providing ants also acquired more infectious Metarhizium than Beauveria (Fig. 3A). This could potentially be caused by differences between the pathogens, such as cuticle attachment speed or conidiospore size (28), affecting their transmission likelihoods or deviations in their ability to resist the ants’ antimicrobial poison (18). Since the behavioral modulation of infected ants was so consistent toward the two pathogens (Fig. 2) it is therefore unsurprising that the ants were successful in reducing superinfection loads of Beauveria below detectable levels, but not Metarhizium. Even if Metarhizium superinfections were not completely prevented they were still strongly and significantly reduced, being 2.5 times lower in ants exposed to the risk-adjusted pathogen dose (Fig. 3B). Hence, modulating the expression of sanitary care is likely an effective way of dealing with an increased susceptibility to heterologous pathogens, for both species of fungus. Studying these pathogen-specific effects in more detail would be an interesting next step and could lead to a deeper understanding of how virulence-dependent differences influence both the hosts’ immune system and their behavioral responses.

Our finding that low-level–infected ants were more aggressive toward their nestmates indicates that the infection itself or a physiological change due to an immune response alters the level of aggression in ants. Similar to our findings in ants, higher irritable or hostile behavior can also be observed in infected vertebrates, including humans (46, 47). These changes in behavior form part of a general sickness behavior that also includes fatigue, depression, and reduced social integration (6, 7). Such changes in behavior are generally considered to be triggered by the immune system through neural and circulatory pathways (48). In ants, a loss of attraction to social cues from the nest or nestmates (49), and hence social isolation from the colony, occurs after Metarhizium infection, close to the death of the individual (40, 41). However, the social isolation of diseased, or generally moribund (50), ants does not involve any aggressive interactions in the colony (41, 49). The observed increase in aggression levels in low-level–infected ants may thus constitute a “partial sickness behavior,” as they do not express signs of disease or all components of a typical sickness behavior (6, 49) and still actively engage in sanitary care of their contaminated nestmates. We found no evidence that the contact between ants during aggression promotes pathogen transfer, since aggression was equally high toward nestmates contaminated with both homologous and heterologous pathogens (Fig. 2A), yet the transfer of pathogens was significantly lower in heterologous combinations (Fig. 3A). Whether these aggressive behaviors are adaptive remains to be determined, but dragging and biting of infected individuals has been observed in honey bees and other ants (41–43) and may potentially play a role in removing contagious individuals from the colony to reduce disease spread (6).

Low-level–infected ants continued to provide sanitary care to their contaminated nestmates, but in a risk-averse manner. Remarkably, we found that by altering the expression of sanitary care ants are able to reduce self-contamination and hence their risk of developing a superinfection with a second, harmful pathogen while caring for their contaminated nestmates. This self-protection is likely achieved by adjusting the relative expression of the components of sanitary care—grooming vs. disinfection. Specifically, low-level–infected ants intensified the spraying of their antimicrobial poison (18) but did not increase the mechanical removal of the infectious particles by grooming of the body surface of nestmates (17) when they were contaminated with the heterologous pathogen. Allogrooming involves close contact with the contaminated nestmate and the uptake of the infectious particles into the ants’ infrabuccal pockets within their mouths (18, 51), while poison spraying represents only the application of their disinfectant. Hence, the reduction in the number of heterologous pathogens being transferred during sanitary care is likely caused by (i) lower levels of allogrooming resulting in reduced contact with contaminated nestmates and (ii) increased rates of poison spraying leading to greater disinfection of the pathogen, and, hence, a decreased likelihood of infection. The capacity to specifically avoid superinfection of detrimental, heterologous pathogens benefits the host but may also benefit the pathogen that has already established an infection, as the two are likely to compete for the same resources within the host (52). However, this may not be the case if the two pathogens have a facilitative interaction and can cooperate within the host (33, 34). Consequently, elucidating the underlying mechanistic basis of the behavioral changes in low-level–infected ants will be necessary to determine the relative importance of an adaptive shift in the host’s response and potential parasite manipulation (53).

Importantly, ants did not simply perform risk-averse sanitary care against pathogens they inherently were more or less susceptible to (e.g., due to their genetic predisposition). Instead, the ants reacted to their individual infection state that induced a change in their disease susceptibility. Our data hence represent a prime example of behavioral plasticity, showing how sanitary care is adjusted as a consequence of the combination of the individual infection state of the care-providing insects and the encountered second pathogen present on the contaminated nestmate. Such behavioral modulation, based on susceptibility changes due to prior experience (54), is also known in flies (55) and humans (e.g., during pregnancy) (9, 56). However, in these cases, the changes lead to an increased avoidance of infectious individuals—a behavior that occurs in healthy animals from crustaceans to primates (57, 58)—rather than a modulation of care behavior, as we report here. The ultimate outcome, the performance of risk-averse sanitary care, rather than the avoidance of diseased group members, highlights the importance of social immunity for the success of insect societies (15). Indeed, although workers are often considered to be expendable they are essential for colony maintenance and the production of new queens, so their health state will have a direct impact on colony fitness (59). Hence, behavioral adaptations, like those presented here, ensure that the worker force of the colony remains healthy and, consequently, can contribute productively to enhance colony fitness. Understanding the protective interplay between immunity and behavior may also pave the way for new approaches to protect social insects, such as important pollinators, from current and future diseases.

Methods

Experimental Procedures.

We used the invasive garden ant L. neglectus, sampled from Jena, Germany, as hosts and the entomopathogenic fungi M. robertsii (strain KVL 13-12) and B. bassiana (KVL 04-004) as pathogens, as described in ref. 20. We exposed ants by topical application of a conidiospore suspension (unless otherwise stated, 0.3 µL of 1 × 109 conidiospores per mL in sterile Triton X; sham treatment of sterile Triton X only). Low-level infections were established as in ref. 20 by rearing five ants for 5 d with one individual that had either been exposed to Metarhizium or Beauveria (noninfected control ants were reared with a sham-treated individual). We quantified low-level infections by CFUs (four control and 16 pathogen replicates of five ants each, 100 ants in total; Fig. S1).

To test for the effect of low-level infections on ant survival upon homologous and heterologous pathogen challenge ants with low-level infections of Metarhizium or Beauveria, as well as noninfected controls, were exposed to either Metarhizium (1 × 109 conidiospores per mL) or Beauveria (5 × 109 conidiospores per mL), subsequently reared alone, and their survival was monitored for 12 d. For all four combinations of homologous and heterologous challenge, each with a respective control, we set up 24 replicates (of each five low-level–infected ants; total of 960 ants) but had to exclude 41 ants that had died before challenge on day five. To test for the effect of simultaneous coexposure we exposed ants to either pathogen alone or in a 50:50 mix and monitored their survival as above (120 ants per treatment, 360 in total).

We recorded the behavior (aggression, allogrooming, and poison spraying) that the contaminated nestmate received, in total, from the five other ants in its rearing group in all six combinations of their infection state (noninfected, homologous, or heterologous prior low-level infection) and pathogen challenge from the contaminated nestmate (Metarhizium or Beauveria), each in 24 replicates (each of five low-level–infected or noninfected control ants, 720 ants in total; video analysis of 1 h per replicate). Additionally, we determined how infection affects interactions with noncontaminated control nestmates (72 replicates of five ants each, 360 ants in total). To determine the number of CFUs developed from viable conidiospores that were transferred from the exposed individual to its nestmates we washed the body surface of the noninfected or Metarhizium- or Beauveria-infected ants (total n = 820 individuals, pooled in 164 replicates of five ants each) and plated the washes on agar plates to count CFUs after 2 wk. To test whether the observed differences in conidiospore transfer translate into a different level of internal superinfection we directly exposed Metarhizium- or Beauveria-infected ants to their heterologous pathogen, in either an amount equivalent to displaying the behavioral change or not (derived from Fig. 3A; 51 replicates of five low-level–infected ants each, total of 255 ants, after exclusion of one outlier sample) and determined their superinfection load by real-time PCR quantification of the fungal ITS2 rRNA gene copies. See SI Methods for details of the experimental procedures. All supporting data are provided in Datasets S1–S5.

Statistical Analysis.

We performed overall models consisting of “pathogen challenge” (Metarhizium or Beauveria) and “infection state” (noninfected or homologous or heterologous low-level infection) and their interaction. If an interaction was nonsignificant we refitted the model without it and tested the significance of the main factors. For survival analyses, we used COXME (Fig. 1). Behavioral data (Fig. 2) and the transfer of conidiospores (Fig. 3A) were analyzed with GLMs. Superinfection load (Fig. 3B) was analyzed separately for the two pathogens using linear mixed effects regressions (LMER), and adjusted the P values for multiple testing. Where post hocs were necessary we used the Tukey procedure and Benjamini–Hochberg correction to account for multiple testing. See SI Methods for detailed statistical procedures and analysis of supplemental data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. M. Steinwender and J. Eilenberg for the fungal strains and the entire Social Immunity Team at IST Austria for support and discussion throughout the project, particularly B. Milutinović, M. A. Fürst, B. Casillas-Pérez, and M. Iglesias. We also thank P. Schmid-Hempel, J. Kurtz, S. A. Frank, C. D. Nunn, M. Schaller, C. Russell, and F. Jephcott for discussion and R. M. Bush, L. V. Ugelvig, M. Sixt, and four anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by European Research Council Starting Grant 240371 (to S.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1713501115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gourley TS, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Ahmed R. Generation and maintenance of immunological memory. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masri L, Cremer S. Individual and social immunisation in insects. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ami F, Rigaud T, Ebert D. The expression of virulence during double infections by different parasites with conflicting host exploitation and transmission strategies. J Evol Biol. 2011;24:1307–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamieson AM, et al. Role of tissue protection in lethal respiratory viral-bacterial coinfection. Science. 2013;340:1230–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.1233632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore J. An overview of parasite-induced behavioral alterations–And some lessons from bats. J Exp Biol. 2013;216:11–17. doi: 10.1242/jeb.074088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shakhar K, Shakhar G. Why do we feel sick when infected—Can altruism play a role? PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002276. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart BL. Biological basis of the behavior of sick animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1988;12:123–137. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(88)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis V, de Barra M, Aunger R. Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:389–401. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarrete CD, Eng SJ, Fessler DMT. Elevated disgust sensitivity in the first trimester of pregnancy: Evidence supporting the compensatory prophylaxis hypothesis. Evol Hum Behav. 2005;26:344–351. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson RJ, Case TI, Oaten MJ. Frequency and recency of infection and their relationship with disgust and contamination sensitivity. Evol Hum Behav. 2009;30:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander RD. The evolution of social behavior. Annu Rev Entomol. 1974;5:325–383. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freeland WJ. Pathogens and the evolution of primate sociality. Biotropica. 1976;8:12–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunn CL, Altizer S. Infectious Disease in Primates. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2006. p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cremer S, Armitage SAO, Schmid-Hempel P. Social immunity. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R693–R702. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cremer S, Pull CD, Fürst MA. Social immunity: Emergence and evolution of colony-level disease protection. Annu Rev Entomol. 2018;63:105–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosengaus RB, Maxmen AB, Coates LE, Traniello JFA. Disease resistance: A benefit of sociality in the dampwood termite Zootermopsis angusticollis (Isoptera: Termopsidae) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 1998;44:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes WOH, Eilenberg J, Boomsma JJ. Trade-offs in group living: Transmission and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ants. Proc Biol Sci. 2002;269:1811–1819. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tragust S, et al. Ants disinfect fungus-exposed brood by oral uptake and spread of their poison. Curr Biol. 2013;23:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tranter C, Hughes WOH. Acid, silk and grooming: Alternative strategies in social immunity in ants? Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2015;69:1687–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Konrad M, et al. Social transfer of pathogenic fungus promotes active immunisation in ant colonies. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, Li G, Sun P, Lei C, Huang Q. Experimental verification and molecular basis of active immunization against fungal pathogens in termites. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15106. doi: 10.1038/srep15106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traniello JFA, Rosengaus RB, Savoie K. The development of immunity in a social insect: Evidence for the group facilitation of disease resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6838–6842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102176599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ugelvig LV, Cremer S. Social prophylaxis: Group interaction promotes collective immunity in ant colonies. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1967–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson ML, Bridges CB, Harper SA. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Influenza vaccination of health-care personnel. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein ZA, Tocco JU, Mantell JE, Smith RA. To hasten Ebola containment, mobilize survivors. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1679–1680. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cremer S, Ugelvig LV, Drijfhout FP, Schlick-Steiner BC, Steiner FM, et al. The evolution of invasiveness in garden ants. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pull CD, Hughes WOH, Brown MJF. Tolerating an infection: An indirect benefit of co-founding queen associations in the ant Lasius niger. Naturwissenschaften. 2013;100:1125–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00114-013-1115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vestergaard S, Butt TM, Bresciani J, Gillespie AT, Eilenberg J. Light and electron microscopy studies of the infection of the western flower thrips Frankliniella occidentalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) by the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1999;73:25–33. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1998.4802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westhus C, et al. Increased grooming after repeated brood care provides sanitary benefits in a clonal ant. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2014;68:1701–1710. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker TN, Hughes WOH. Adaptive social immunity in leaf-cutting ants. Biol Lett. 2009;5:446–448. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadd BM, Schmid-Hempel P. A distinct infection cost associated with trans-generational priming of antibacterial immunity in bumble-bees. Biol Lett. 2009;5:798–801. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulrich Y, Schmid-Hempel P. Host modulation of parasite competition in multiple infections. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279:2982–2989. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank SA. Models of parasite virulence. Q Rev Biol. 1996;71:37–78. doi: 10.1086/419267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffin AS, West SA, Buckling A. Cooperation and competition in pathogenic bacteria. Nature. 2004;430:1024–1027. doi: 10.1038/nature02744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmid-Hempel P. Variation in immune defence as a question of evolutionary ecology. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:357–366. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vilcinskas A, Matha V, Götz P. Inhibition of phagocytic activity of plasmatocytes isolated from Galleria mellonella by entomogenous fungi and their secondary metabolites. J Insect Physiol. 1997;43:475–483. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keller S, Kessler P, Schweizer C. Distribution of insect pathogenic soil fungi in Switzerland with special reference to Beauveria brongniartii and Metarhizium anisopliae. BioControl. 2003;48:307–319. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinwender BM, et al. Molecular diversity of the entomopathogenic fungal Metarhizium community within an agroecosystem. J Invertebr Pathol. 2014;123:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ugelvig LV, et al. The introduction history of invasive garden ants in Europe: Integrating genetic, chemical and behavioural approaches. BMC Biol. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bos N, Lefèvre T, Jensen AB, d’Ettorre P. Sick ants become unsociable. J Evol Biol. 2012;25:342–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leclerc JB, Detrain C. Ants detect but do not discriminate diseased workers within their nest. Naturwissenschaften. 2016;103:70. doi: 10.1007/s00114-016-1394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richard FJ, Holt HL, Grozinger CM. Effects of immunostimulation on social behavior, chemical communication and genome-wide gene expression in honey bee workers (Apis mellifera) BMC Genomics. 2012;13:558. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baracchi D, Fadda A, Turillazzi S. Evidence for antiseptic behaviour towards sick adult bees in honey bee colonies. J Insect Physiol. 2012;58:1589–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reber A, Purcell J, Buechel SD, Buri P, Chapuisat M. The expression and impact of antifungal grooming in ants. J Evol Biol. 2011;24:954–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes WOH, et al. Density-dependence and within-host competition in a semelparous parasite of leaf-cutting ants. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hart BL. Behavioral adaptations to pathogens and parasites: Five strategies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1990;14:273–294. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loehle C. Social barriers to pathogen transmission in wild animal populations. Ecology. 1995;76:326–335. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leclerc JB, Detrain C. Loss of attraction for social cues leads to fungal-infected Myrmica rubra ants withdrawing from the nest. Anim Behav. 2017;129:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heinze J, Walter B. Moribund ants leave their nests to die in social isolation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:249–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eisner T, Happ GM. The infrabuccal pocket of a formicine ant: A social filtration device. Psyche (Stuttg) 1962;69:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. Let your enemy do the work: Within-host interactions between two fungal parasites of leaf-cutting ants. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271(Suppl 3):S104–S106. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes DP, Brodeur J, Thomas F. Host Manipulation by Parasites. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hughes DP, Cremer S. Plasticity in anti-parasite behaviours and its suggested role in invasion biology. Anim Behav. 2007;74:1593–1599. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vale PF, Jardine MD. Infection avoidance behavior: Viral exposure reduces the motivation to forage in female Drosophila melanogaster. Fly (Austin) 2017;11:3–9. doi: 10.1080/19336934.2016.1207029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones BC, et al. Menstrual cycle, pregnancy and oral contraceptive use alter attraction to apparent health in faces. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272:347–354. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poirotte C, et al. Mandrills use olfaction to socially avoid parasitized conspecifics. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1601721. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Behringer DC, Butler MJ, Shields JD. Ecology: Avoidance of disease by social lobsters. Nature. 2006;441:421. doi: 10.1038/441421a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dainat B, Evans JD, Chen YP, Gauthier L, Neumann P. Predictive markers of honey bee colony collapse. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.