Significance

Young Black men are stereotyped as threatening, which can have grave consequences for interactions with police. We show that these threat stereotypes are even greater for tall Black men, who face greater discrimination from police officers and elicit stronger judgments of threat. We challenge the assumption that height is intrinsically good for men. White men may benefit from height, but Black men may not. More broadly, we demonstrate how demographic factors (e.g., race) can influence how people interpret physical traits (e.g., height). This difference in interpretation is a matter not of magnitude but of meaning: The same trait is positive for some groups of people but negative for others.

Keywords: racial stereotyping, height, threat, person perception, intersectionality

Abstract

Height seems beneficial for men in terms of salaries and success; however, past research on height examines only White men. For Black men, height may be more costly than beneficial, primarily signaling threat rather than competence. Three studies reveal the downsides of height in Black men. Study 1 analyzes over 1 million New York Police Department stop-and-frisk encounters and finds that tall Black men are especially likely to receive unjustified attention from police. Then, studies 2 and 3 experimentally demonstrate a causal link between perceptions of height and perceptions of threat for Black men, particularly for perceivers who endorse stereotypes that Black people are more threatening than White people. Together, these data reveal that height is sometimes a liability for Black men, particularly in contexts in which threat is salient.

“When you deal with the police, you must be careful. You are big and they will automatically see you as a threat.” — Charles Coleman, Jr. (6′4″ Black attorney/writer), quoting his mother

Charles Coleman, Jr. evoked his mother’s warning when he wrote about Eric Garner, an unarmed man choked to death by police. Garner was both Black and 6′3″ tall. Coleman highlights the perils of “occupying a Black body that is inherently threatening,” arguing that tall Black men receive disproportionate attention from police officers (1). This argument evokes the “black brute” archetype, which portrays Black men as apelike savages who use their imposing physical frame to threaten others (2, 3). Although Black men face stereotypes of aggression and threat (4–6), tall Black men may find themselves perceived as especially threatening.

The idea that height has negative consequences contrasts with previous psychological research on height in men, which argues that taller is better. Research finds that tall men seem healthier, more intelligent, more successful, and more physically attractive (7–9). Tall men also stand a greater chance of being hired (10), making more money (11, 12), gaining promotions (13, 14), and winning leadership positions (7, 15).

However, this research almost exclusively explores perceptions of White men (Table S1), who are already positively stereotyped as competent and intelligent (16, 17). On the other hand, Black men are negatively stereotyped; they are seen as hostile, aggressive, and threatening (e.g., refs. 17–20) and are associated with guns (4, 5). For Black men, height may be more often interpreted as a sign of threat instead of competence.

Thus, being tall may not be inherently good or bad for men. Instead, the accessibility of other traits, such as competence and threat, may influence how people interpret height. Classic work in social psychology demonstrates similar effects: Whether a target is initially described as “warm” or “cold” changes how people interpret the target’s other traits (e.g., intelligent, industrious) (21). Considerable research demonstrates that Black men are specifically stereotyped as physically threatening and imposing (22, 23). For this reason, height may impact judgments of threat more strongly for Black men than for White men.

The Present Research

In three studies, we test whether taller Black men are judged as more threatening than shorter Black men and than both taller and shorter White men. We first examined whether New York City police officers disproportionately stopped and frisked tall Black men from 2006 to 2013 (study 1). We then investigated whether height increases threat judgments more for Black men than for White men by manipulating height both visually (study 2) and descriptively (study 3).

Cultural Stereotypes Pilot

Before conducting these three studies, we first conducted a pilot examining participants’ knowledge of cultural stereotypes, testing whether participants endorse knowledge of stereotypes that tall Black men are seen as especially threatening and tall White men are seen as especially competent. Results showed that cultural stereotypes of threat are increased by tallness more for Black targets than for White targets and, conversely, that cultural stereotypes of competence are increased by tallness more for White targets than for Black targets. Full reporting for this pilot is provided in Pilot Study: Cultural Stereotypes About Height and Race; a graph summarizing the results is shown in Fig. S1.

Results

Study 1: New York Police Department Stop-and-Frisk.

In 2013, Judge Shira Scheindlin of the Federal District Court in New York ruled that the New York Police Department’s (NYPD’s) stop-and-frisk program was unconstitutional because of its clear history of racial discrimination (24). Black and Hispanic people faced disproportionate odds of being stopped by police officers, despite the fact that this “racial profiling” was ineffective. In study 1 we tested whether tall Black men were especially likely to be stopped by NYPD officers.

Before analysis, we cleaned the dataset and made three restrictions. (i) We only used data for non-Hispanic Black and White males, avoiding issues with different distributions of height in the population (i.e., Hispanics are shorter than non-Hispanics; women are shorter than men). (ii) We restricted our data to include only people between 5′4″ and 6′4″. This range in height includes over 98% of Black and White males and prevents outliers (particularly those created by clerical errors) from influencing our results. (iii) We restricted our data to include only people of weights between 100 and 400 lb to prevent outliers created by clerical errors.

Recent work demonstrates that young Black men are perceived as taller and more threatening than young White men, controlling for actual height (22). To account for the alternate explanation that police officers simply perceived Black men as taller than White men (25), we analyzed only cases in which suspects provided photographic identification, which almost always lists height alongside other information that cannot be guessed or estimated, such as date of birth (thus making it highly probable that officers record the listed value for height, rather than estimating it) (26). These restrictions left us with 1,073,536 valid targets for analysis.

The stop-and-frisk dataset is large and includes numerous potential dependent variables. For our analysis, we focus on police officers’ decisions to stop individuals, as this decision is made before any interactions with police, making it more reliant on person perception (27). We recognize the potential issue of flexible analyses and partly address this issue by estimating standardized effect sizes for many variables, which allows comparison of the relative magnitude of effects (especially given that the sample size is large enough to allow accurate estimation of effect size).

We accounted for target weight and the interaction of height and weight to isolate height as a predictor (12). Furthermore, to address an ecological explanation for race effects (28), we nested our data within precinct (to account for variability in geographical factors such as crime rate and land value), included precinct-level felony rates (from 2005–2013), and also included a variable in which officers report whether the stop was made in a high-crime area. Finally, because some research suggests that only young Black men are stereotyped as threatening (29), we include age and the interaction between height and age in our model.

Ratio of Black to White stops.

Under stop-and-frisk rules, police officers had the authority to stop anyone they deemed suspicious or threatening. If tall Black men seem especially threatening, then the ratio of Black to White stops (i.e., how many Black men are stopped per White man) should increase with height.

Accounting for precinct-level felonies, weight, age, and perceived local crime, height still showed a meaningful main effect, B = 0.079, t(1,073,526) = 23.98, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.070, 0.085]. At 5′4″, police stopped 4.5 Black men for every White man; at 5′10″, police stopped 5.3 Black men for every White man; and at 6′4″, police stopped 6.2 Black men for every White man. These results suggest that taller Black men face a greater risk of being stopped than shorter Black men.

Notably, the ratio of Black to White stops was also greater for heavier men, B = 0.041, t(1,073,526) = 11.80, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.035, 0.048]. At 115 lb, police stopped 4.5 Black men for every White man; at 175 lb (the average weight in the dataset), police stopped 5.2 Black men for every White man; and at 235 lb, police stopped 5.7 Black men for every White man. Finally, height and weight interacted, B = 0.047, t(1,073,526) = 15.71, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.041, 0.053], such that each 1-SD increase in weight increases the standardized effect of height by 0.047. Because weight estimates were not provided on photograph IDs (hereafter, “photo IDs”), we interpret these results with caution.

We also found effects for other variables in the model. Unsurprisingly, areas with more crime, as reported by police and captured in precinct-level data, exhibit higher ratios of Black to White stops. The ratio of Black to White stops was also larger for younger men. Interestingly, height and age interacted, such that height’s effect on the ratio of Black to White stops was larger for older Black men. See Table S2 for the full coefficients and a replication of results with both photo and verbal IDs included.

Discussion.

Study 1 demonstrates that tall Black men receive disproportionate attention from police officers. During 8 y of NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program, tall Black men were particularly likely to face unjustified stops by police officers, and these patterns were not explained by biased height estimates (since officers received photo IDs).

In the next two studies, we test whether these results might be explained by an interaction between race and height, such that tallness primarily increases perceptions of threat for Black men and primarily increases perceptions of competence for White men.

Study 2: Manipulating Height with Perspective.

We experimentally manipulated height and race to test whether they interact to influence judgments of threat and competence. To manipulate height, we took photographs of 16 young men—eight Black and eight White—from two perspectives: above the target and below the target. These different perspectives naturalistically manipulated the experience of encountering someone who is tall or short. A manipulation check indicated that perspective significantly influenced participants’ free response estimates of target height, b = 1.78, F(1, 427) = 16.42, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.91, 2.65], such that targets that were looking down were perceived as taller [mean (M) = 71.6 in.] than targets that were looking up (M = 69.8 in.). See Method for a more detailed description of the perspective manipulation.

Participants rated 16 photographs for adjectives describing both threat and competence. Then, because we expected judgments to depend on participants’ individual beliefs about Black and White people, we assessed participants’ beliefs that Black people are more threatening than White people. We predicted that stronger beliefs about Black threat (BaBT) would increase participants’ tendency to identify tall Black men as especially threatening. We also tested the complementary hypothesis that stronger BaBT might make tall White men seem especially competent. We preregistered these predictions at https://aspredicted.org/465w9.pdf. We also previously conducted another study with a nearly identical design; the results of this study are detailed in Previous Iteration of Study 2.

Race, height, and racial stereotypes.

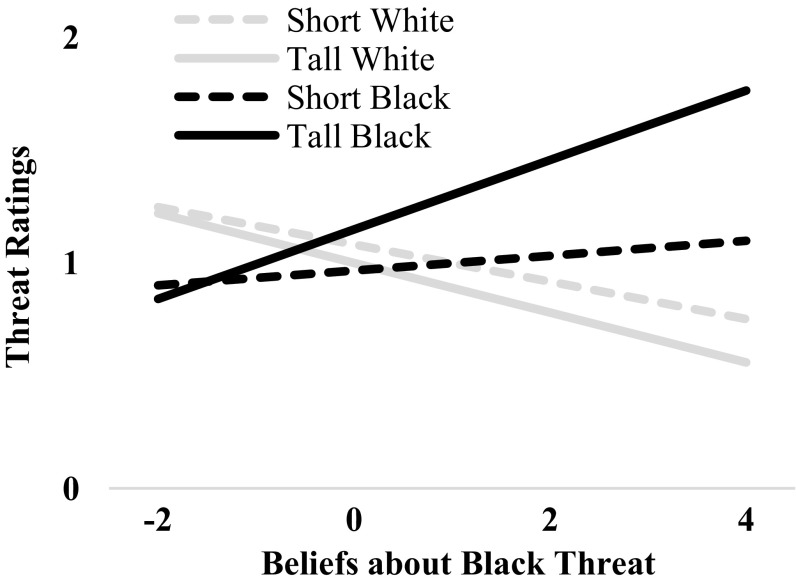

To test whether those with higher BaBT would judge tall Black men as especially threatening, we fit a three-way multilevel model predicting threat with race, height, and BaBT. This analysis yielded an expected two-way interaction between target race and BaBT, b = 0.19, F(1, 437) = 61.40, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.14, 0.23], such that those higher in BaBT rated Black men as more threatening relative to White men. Importantly, this analysis also yielded the key three-way interaction, b = 0.15, F(1, 2,081) = 10.97, P = 0.001, 95% CI [0.06, 0.24]. No moderating effect of participant gender emerged (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study 2 ratings of threat by race, height, and BaBT. Positive values indicate beliefs that Black people are more threatening than White people; negative values indicate beliefs that White people are more threatening than Black people.

For Black targets, the two-way interaction between height and BaBT was significant, b = 0.12, t(833) = 3.67, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.06, 0.19]: Those higher in BaBT saw tall black men as especially threatening. For White targets, this two-way interaction was not significant, b = −0.03, t(834) = −0.83, P = 0.41, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.04]. These results suggest that the predictive utility of BaBT is moderated by height for stereotype-relevant targets (Black men) but not for stereotype-irrelevant targets (White men). See Additional Analyses for Study 2 for BaBT main effects by race and height.

Although BaBT captures the endorsement of stereotypes about threat and not competence, we nevertheless tested for a three-way interaction with competence ratings. We found an expected two-way interaction between target race and BaBT, b = 0.16, F(1, 459) = 70.27, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.20], such that those higher in BaBT rated White men as more competent relative to Black men. We also found a three-way interaction, b = 0.12, F(1, 1,097) = 7.52, P = 0.006, 95% CI [0.03, 0.20], such that BaBT predicted competence especially strongly for tall White men. Participant gender did not moderate effects. This interaction is further broken down statistically (Additional Analyses for Study 2) and graphically (Fig. S2).

Suppressed height effects.

Height did not increase threat for White men, nor did it increase competence for Black men. However, our pilot study revealed main effects of height on stereotypes of both competence and threat. One possible explanation for this null finding is that, for judgments of tall White men, perceived competence suppressed gains in threat, and, for judgments of tall Black men, perceived threat suppressed gains in competence. Because we found significant race by height interactions for both threat and competence at mean levels of BaBT, we were able to conduct Sobel mediations using the entire sample to test these hypotheses.

For White targets, we found a negative indirect effect of height on threat, ab = −0.04, z = −4.30, P < 0.001; being taller makes targets seem more competent and thus less threatening. Once this indirect effect was accounted for, height no longer decreased threat for White men, b = −0.05, t(1,406) = −1.40, P = 0.16. Conversely, for Black targets, we found a negative indirect effect of height on competence, ab = −0.09, z = −6.07, P < 0.001; being taller makes targets more threatening and thus less competent. Notably, once this indirect effect was accounted for, height increased perceived competence for Black targets, b = 0.09, t(1,406) = 2.75, P = 0.006, suggesting that height may be beneficial for Black men in contexts that sufficiently nullify concerns about threat (e.g., the corporate boardroom).

Discussion.

Study 2 experimentally demonstrates that height amplifies threat for Black men and competence for White men, particularly for perceivers who endorse beliefs that Black people are more threatening than White people. Study 2 also found indirect negative effects of height on competence for Black men and threat for White men.

Study 3: Manipulating Height with Descriptions.

Although the photographs from study 2 have naturalistic validity, they may also confound height with intimidation (30). We address this concern by manipulating height with text vignettes (e.g., “As you approach each other, you can see that he is very short/quite tall”) and manipulating race with standardized photographs. See Textual Descriptions of Height Used in Study 3 for text descriptions of height.

Participants rated 16 targets on the same threat and competence adjectives used in study 2. They then completed the BaBT scale. As in the previous experiment, we predicted that those higher in BaBT would make especially strong threat judgments for tall Black men and especially strong competence judgments for tall White men. We preregistered these predictions at https://aspredicted.org/sp3aj.pdf.

Race, height, and racial stereotypes.

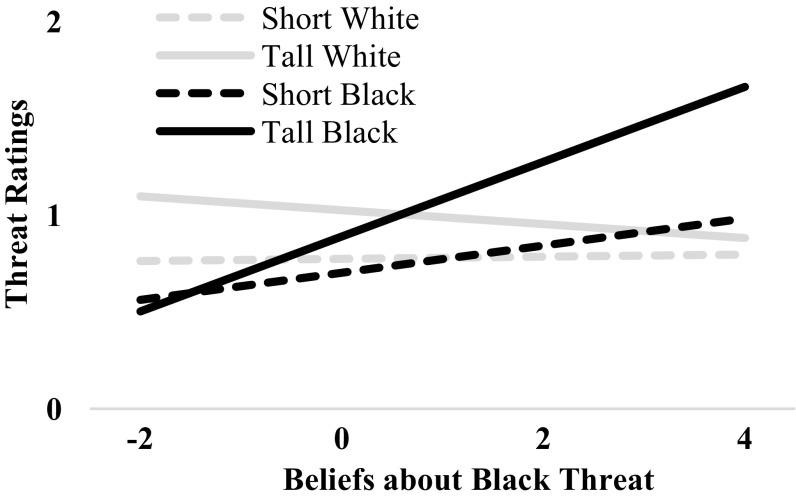

We again fit a multilevel model predicting threat with race, height, and BaBT. We replicated the key findings of study 2; those higher in BaBT rated Black men as more threatening relative to White men, b = 0.15, F(1, 374) = 30.83, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.10, 0.20], and this effect was especially large for tall Black men, b = 0.16, F(1, 1,548) = 9.04, P = 0.003, 95% CI [0.06, 0.27]. Participant gender did not moderate effects (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Study 3 ratings of threat by race, height, and BaBT. Positive values indicate beliefs that Black people are more threatening than White people; negative values indicate beliefs that White people are more threatening than Black people.

We also replicated the competence results of study 2: Those higher in BaBT rated White men as more competent relative to Black men, b = 0.11, F(1, 320) = 20.36, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.17], and this effect was especially large for tall White men, b = 0.10, F(1, 1,518) = 3.78, P = 0.052, 95% CI [−0.00, 0.20]. No moderating effect of participant gender emerged. See Additional Analyses for Study 3 for the breakdown of both the threat and competence interactions.

Discussion.

Study 3 addressed stimuli concerns from study 2 and again demonstrated that, for those higher in BaBT, tall Black men seem especially threatening compared with short Black men and both short and tall White men.

General Discussion

In three studies, we showed that taller is not always better; although tall White men may benefit from increased perceptions of competence, tall Black men are burdened with increased perceptions of threat. We first revealed that NYPD police officers stopped tall Black men at a disproportionately high rate (study 1). We then demonstrated that, for perceivers who endorse stereotypes that Black people are more threatening than White people, tall Black men seem especially threatening (studies 2 and 3).

Previous research has amply demonstrated that people may interpret traits and behaviors as positive or negative depending on the accessibility of other concepts. For example, a classic study revealed that a target’s ambiguous actions are negatively evaluated when participants are first primed with hostility-related traits (versus kindness-related traits) (31). Racial stereotypes alter the accessibility of traits during person perception, which influences how people interpret other traits—in this case, height. For people who already perceive Black men as threatening, height confers extra threat.

Our findings have important implications when considered alongside recent research demonstrating that young Black men are perceived as taller and more muscular than young White men of equivalent size, which causes them to also seem more threatening to non-Black participants (22). The present findings suggest that the negative consequences of these biased height perceptions (i.e., increased threat perceptions) hinge on how strongly the perceiver believes that Black people are threatening (thus interpreting height as a sign of threat).

Height may also interact with more subtle cues of race, such as Afrocentric features (32, 33), and the effect of height may be determined by contextual cues. Once we controlled for perceived threat in study 2, taller Black men were actually perceived as more competent than shorter Black men. When competence is clearly more relevant than threat, Black men may also benefit from height. Alternately, Black men may also benefit from height if they possess other traits that reduce threat, such as babyfacedness (34).

More broadly, these results highlight the importance of intersections between social categories and physical traits. Just as social categories such as race, gender, age, and socioeconomic status intersect in important ways with each other (35, 36), so too do they influence the impact of physical factors such as height (37), weight (38), babyfacedness (34), and facial attractiveness (39).

We recognize that our findings do not necessarily generalize to perceptions of women. We limited our targets to men because police profiling and threatening stereotypes both target Black males. However, future research should investigate whether the same race–height interactions apply for women. Previous work indicates that White women enjoy at least some of the same benefits of height as White men (7), but no work to date has investigated the effects of height for perceptions of Black women.

We also recognize the potential role of weight in perceptions of threat. Consistent with others’ previous work (22, 25), our stop-and-frisk analyses suggest that weight also plays a key role in judgments of suspicion. Because of accuracy concerns about the weight estimates, which may have been biased (22), and the relatively large effect size of height, we chose to focus on height; however, future work should further investigate how height and weight combine with categories such as race and gender to influence judgments.

Being tall is often discussed as a wholly good trait, so much so that Randy Newman wrote a satirical song that lists reasons why “short people got no reason to live.” However, height means something different for Black men: Height amplifies already problematic perceptions of threat, which can lead to harassment and even injury. When Charles Coleman, Jr.’s mother told him that he “was big and they would automatically see [him] as a threat,” she eloquently summarized what we empirically showed—for Black men, being tall may be less a boon and more a burden.

Method

The University of North Carolina Institutitional Review Board (IRB) approved studies 2 and 3 as well as the pilot study. Participants in these studies indicated consent electronically and received debriefing at the end of the studies. Study 1 did not use human subjects and required no IRB approval.

Study 1 data are available at www1.nyc.gov/site/nypd/stats/reports-analysis/stopfrisk.page. Data for the pilot study, study 2, and study 3 are available in Supporting Information.

Study 1.

We combined 8 y of publicly available data (2006–2013) documenting the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk program. These data include information about every person stopped as part of the program, including race, age, gender, height, weight, and whether the person was frisked, searched, arrested, or issued a summons. Notably, we only analyzed stops in which officers received photo ID, ensuring the relative accuracy of the reported height and age (26).

We cleaned the data by filtering cases with clear errors (i.e., a large number of people had ages of 99 y or higher, or birth years of 1900). We also restricted the dataset to non-Hispanic Black and White males. By focusing on non-Hispanic Black and White males, we minimized problems of distribution: Adult Black and White males have nearly identical means and distributions of height (40).

Study 2.

Participants and design.

Two hundred participants (73% White, 6% Black, 42% women, Mage = 36 y) completed a 2 × 2 [Target Race: Black, White by Target Perspective: Looking Down (Tall), Looking Up (Short)] within-subjects study. With n = 200 at level 2 and n = 16 at level 1 and a subject slope variance of 0.39, we had ∼88% power to detect a small cross-level interaction (41).

Materials.

Creating stimuli to manipulate height and race.

To create stimuli, we photographed 16 male students from the University of North Carolina. Eight students were White, and eight were Black. We photographed each student from two perspectives: looking up and looking down. We intended to manipulate perceived height: If someone is looking down on you, they are likely taller, but if they are looking up at you, they are likely shorter. This perspective manipulation allowed us to manipulate height in a within-subjects design, addressing both power and stimulus sampling issues (42). In particular, our attention to stimulus sampling reduces the likelihood that our effects were driven by the traits of a particular photograph and minimizes the possibility that small variations in luminance or target size explain our effects (42). See Fig. 3 for examples of stimuli.

Fig. 3.

Two of the 16 male students whose photographs were used in study 2. The men in the photographs on the left (looking down) were perceived as taller than the same men in the photographs on the right (looking up).

To check whether our manipulation of height actually worked, we predicted the estimated height of each target by target perspective. The analysis revealed a main effect of target perspective on estimated height, b = 1.78, F(1, 427) = 16.42, P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.91, 2.65], such that targets who were looking down were perceived as taller (M = 71.6 in.) than targets who were looking up (M = 69.8 in.). We found no main effect of race, b = −0.39, F(1, 427) = 0.80, P = 0.37, 95% CI [−1.26, 0.48], although we did find a race by perspective interaction, b = 1.77, F(1, 2,322) = 4.12, P = 0.043, 95% CI [0.06, 3.48], such that perspective had a larger effect for Black targets. Simple main effects show that Black looking-up targets were perceived as 1.3 in. shorter than White looking-up targets, b = −1.27, t(899) = 2.05, P = 0.041, 95% CI [−2.49, −0.05]. The difference between Black and White looking-down targets was not significant, b = 0.49, t(3,018) = 0.80, P = 0.42, 95% CI [−0.72, 1.72].

BaBT.

Participants answered questions adapted from the General Social Survey (gss.norc.org/). We used these questions because they are less confounded with political beliefs than other scales (43) and directly target stereotypes of Black threat. Participants provided their attitudes toward Black, Hispanic, and White people on seven-point bipolar scales for “nonviolent/violent,” “nonthreatening/threatening,” “nonaggressive/aggressive,” and “not dangerous/dangerous.” Questions about Hispanic targets were included to decrease the focus on Black and White targets and reduce the effect of social desirability on responses.

To create an index variable representing participants’ BaBT, we subtracted participants’ attitudes about White targets from their attitudes about Black targets to capture the relative difference in participants’ attitudes (believing Blacks are more violent than Whites) rather than their overall attitudes (believing people are generally violent regardless of race). Then, we averaged the four difference scores together.

Procedure.

Participants rated 16 photographs of college-aged males on five traits: competent, likable, attractive, threatening, and aggressive. These photographs were counterbalanced, such that each target was seen by half of the participants as looking up and by the other half as looking down. The first item captured competence, and the last two items captured threat. We initially included “likable” and “attractive” as competence items but removed them as suggested by reviewers and the editor; this change did not influence our results. Participants also estimated the height of each target, in inches. After completing these ratings, participants completed the BaBT scale.

Analytic strategy.

We again accounted for between-participant variance by using hierarchical linear modeling, with responses nested within participants. We allowed slopes to vary for both race and perspective manipulations to provide a more precise model and allow cross-level interaction with BaBT.

Study 3.

Participants and design.

Two hundred eight participants (75% White, 10% Black, 61% women, Mage = 38 y) completed a 2 × 2 (Target Race: Black, White by Described Height: Tall, Short) within-subjects study. This study sought to replicate the three-way interaction of study 2 with stimuli that more specifically manipulate height. With n = 208 at level 2 and n = 8 at level 1 and a subject slope variance of 0.28, we had ∼90% power to detect a small cross-level interaction (41).

Materials and procedure.

To manipulate race, we used 20 Black male and 20 White male faces from the Chicago Face Database (44). These faces were chosen based on age; all targets were between 21 and 29 y old. To manipulate height, we described an encounter with each target in which the target was either taller or shorter than the participant. Participants rated eight targets using the same competence and threat items as in study 2. Participants then completed the BaBT scale. The analytic strategy was identical to that of study 2.

Preregistration Details.

We note a few points of discrepancy between our preregistrations and the presented results. (i) The study 2 preregistration did not include the specific hypothesis that people higher in BaBT would judge tall White men as especially competent. (ii) The study 3 preregistration notes the inclusion of BaBT as a potential moderator but does not explicitly state the specific hypotheses. (iii) The specific traits used in the “competence” and “threat” composites were not listed in the preregistrations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lindsey Helms for creating images for study 2 and Alexander Aspuru for copyediting.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1714454115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Coleman C. 2014 Eric Garner: Tall, dark, and threatening. EBONY. Available at www.ebony.com/news-views/eric-garner-tall-dark-and-threatening-405. Accessed March 26, 2017.

- 2.Jackson RL. Scripting the Black Masculine Body: Identity, Discourse, and Racial Politics in Popular Media. SUNY Press; Albany, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goff PA, Eberhardt JL, Williams MJ, Jackson MC. Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:292–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correll J, Park B, Judd CM, Wittenbrink B. The police officer’s dilemma: Using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83:1314–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne BK. Prejudice and perception: The role of automatic and controlled processes in misperceiving a weapon. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:181–192. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trawalter S, Todd AR, Baird AA, Richeson JA. Attending to threat: Race-based patterns of selective attention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2008;44:1322–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaker NM, et al. The height leadership advantage in men and women: Testing evolutionary psychology predictions about the perceptions of tall leaders. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2013;16:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson L, Ervin K. Height stereotypes of women and men: The liabilities of shortness for both sexes. J Soc Psychol. 1992;132:433–445. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shepperd JA, Strathman AJ. Attractiveness and height: The role of stature in dating preference, frequency of dating, and perceptions of attractiveness. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1989;15:617–627. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman SD. The presentation of shortness in everyday life—Height and heightism in American society: Toward a sociology of stature. In: Feldman SD, Thielbar GW, editors. Life Styles: Diversity in American Society. Little, Brown and Company; Boston: 1975. pp. 427–442. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cinnirella F, Winter JK. 2009 Size matters! Body height and labor market discrimination: A cross-European analysis. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1443091. Accessed February 5, 2016.

- 12.Judge TA, Cable DM. The effect of physical height on workplace success and income: Preliminary test of a theoretical model. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89:428–441. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egolf DB, Corder LE. Height differences of low and high job status, female and male corporate employees. Sex Roles. 1991;24:365–373. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gawley T, Perks T, Curtis J. Height, gender, and authority status at work: Analyses for a national sample of Canadian workers. Sex Roles. 2009;60:208–222. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazur A, Mazur J, Keating C. Military rank attainment of a west point class: Effects of cadets’ physical features. Am J Sociol. 1984;90:125–150. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82:878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wittenbrink B, Judd CM, Park B. Evidence for racial prejudice at the implicit level and its relationship with questionnaire measures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:262–274. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devine PG, Elliot AJ. Are racial stereotypes really fading? The Princeton trilogy revisited. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:1139–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaertner SL, McLaughlin JP. Racial stereotypes: Associations and ascriptions of positive and negative characteristics. Soc Psychol Q. 1983;46:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurwitz J, Peffley M. Public perceptions of race and crime: The role of racial stereotypes. Am J Pol Sci. 1997;41:375–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asch SE. Forming impressions of personality. J Abnorm Psychol. 1946;41:258–290. doi: 10.1037/h0055756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson JP, Hugenberg K, Rule NO. Racial bias in judgments of physical size and formidability: From size to threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2017;113:59–80. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cottrell CA, Neuberg SL. Different emotional reactions to different groups: A sociofunctional threat-based approach to “prejudice”. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:770–789. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein J. 2013 Judge rejects New York’s stop-and-frisk policy. NY Times. Available at www.nytimes.com/2013/08/13/nyregion/stop-and-frisk-practice-violated-rights-judge-rules.html. Accessed March 19, 2017.

- 25.Milner AN, George BJ, Allison DB. Black and Hispanic men perceived to be large are at increased risk for police frisk, search, and force. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manfredi V. 2015 Privacy implications of New York City’s stop-and-frisk data. Available at https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/291/. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- 27.Macdonald J, Stokes RJ. Race, social capital, and trust in the police. Urban Aff Rev. 2006;41:358–375. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams KEG, Sng O, Neuberg SL. Ecology-driven stereotypes override race stereotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:310–315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519401113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steffensmeier D, Ulmer J, Kramer J. The interaction of race, gender, and age in criminal sentencing: The punishment cost of being young, black, and male. Criminology. 1998;36:763–798. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hehman E, Leitner JB, Gaertner SL. Enhancing static facial features increases intimidation. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013;49:747–754. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srull TK, Wyer RS. Category accessibility and social perception: Some implications for the study of person memory and interpersonal judgments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;38:841–856. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blair IV, Judd CM, Sadler MS, Jenkins C. The role of Afrocentric features in person perception: Judging by features and categories. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83:5–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberhardt JL, Davies PG, Purdie-Vaughns VJ, Johnson SL. Looking deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:383–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livingston RW, Pearce NA. The teddy-bear effect: Does having a baby face benefit black chief executive officers? Psychol Sci. 2009;20:1229–1236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang SK, Bodenhausen GV. Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:547–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goff PA, Kahn KB. How psychological science impedes intersectional thinking. Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race. 2013;10:365–384. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce CA. Body height and romantic attraction: A meta-analytic test of the male-taller norm. Soc Behav Personal. 1996;24:143–149. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stake J, Lauer ML. The consequences of being overweight: A controlled study of gender differences. Sex Roles. 1987;17:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson LA, Hunter JE, Hodge CN. Physical attractiveness and intellectual competence: A meta-analytic review. Soc Psychol Q. 1995;58:108–122. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDowell MA, Fryar CD, Ogden CL, Flegal KM. 2008. Anthropometric Reference Data for Children and Adults: United States, 2003–2006, Vital Health and Statistics (National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD), DHHS Publication No. 2016–1604.

- 41.Mathieu JE, Aguinis H, Culpepper SA, Chen G. Understanding and estimating the power to detect cross-level interaction effects in multilevel modeling. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97:951–966. doi: 10.1037/a0028380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wells GL, Windschitl PD. Stimulus sampling and social psychological experimentation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1999;25:1115–1125. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sears DO, Henry PJ. The origins of symbolic racism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:259–275. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma DS, Correll J, Wittenbrink B. The Chicago face database: A free stimulus set of faces and norming data. Behav Res Methods. 2015;47:1122–1135. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.