Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: ageing, HIV, model, noncommunicable diseases, Zimbabwe

Abstract

Objectives:

We aim to characterize the future noncommunicable disease (NCD) burden in Zimbabwe to identify future health system priorities.

Methods:

We developed an individual-based multidisease model for Zimbabwe, simulating births, deaths, infection with HIV and progression and key NCD [asthma, chronic kidney disease (CKD), depression, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, breast, cervical, colorectal, liver, oesophageal, prostate and all other cancers]. The model was parameterized using national and regional surveillance and epidemiological data. Demographic and NCD burden projections were generated for 2015 to 2035.

Results:

The model predicts that mean age of PLHIV will increase from 31 to 45 years between 2015 and 2035 (compared with 20–26 in uninfected individuals). Consequently, the proportion suffering from at least one key NCD in 2035 will increase by 26% in PLHIV and 6% in uninfected. Adult PLHIV will be twice as likely to suffer from at least one key NCD in 2035 compared with uninfected adults; with 15.2% of all key NCDs diagnosed in adult PLHIV, whereas contributing only 5% of the Zimbabwean population. The most prevalent NCDs will be hypertension, CKD, depression and cancers. This demographic and disease shift in PLHIV is mainly because of reductions in incidence and the success of ART scale-up leading to longer life expectancy, and to a lesser extent, the cumulative exposure to HIV and ART.

Conclusion:

NCD services will need to be expanded in Zimbabwe. They will need to be integrated into HIV care programmes, although the growing NCD burden amongst uninfected individuals presenting opportunities for additional services developed within HIV care to benefit HIV-negative persons.

Introduction

Since 2000, an unprecedented global effort to increase access to HIV treatment has put 46% of persons living with HIV (PLHIV) on antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally [1]. Effective ART has extended life expectancy of PLHIV, and in the context of maturing HIV-treatment programs and a stabilizing HIV epidemic, we are seeing an ageing population of PLHIV [2–5]. This introduces new challenges and pressures on ART programmes, as in addition to achieving 90 : 90 : 90 targets and moving to ‘test and treat’ PLHIV will increasingly suffer from age-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs).

A recent model-based study provided the first insight into the shifting disease burden amongst ageing PLHIV, finding that by 2030, mean age of PLHIV in The Netherlands could increase from 43.9 years in 2010 to 56.6 years, with 84% suffering from at least one NCD and 54% taking at least one co-medication (in addition to HIV medication) [6]. The study highlighted the clinical impact of the rising burden of NCDs, estimating that 40% of patients may experience complications because of contraindication or drug interactions with currently recommended ART regimens by 2030 [6].

Although demographic changes in sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries with large HIV epidemics lags behind that of Western and Central Europe, similar shifts can be expected in the coming decades [7,8]. The associated evolving disease burden will exert significant pressure on care provision, particularly in settings wherever NCD management continues to remain specialized and access to services are limited. The emerging NCD epidemic may have important implications for ART programs and wider national health services. Substantial planning and strategic changes to service integration may be needed to sustain and build upon health gains achieved to date, particularly where health-care systems mainly provide episodic care for acute symptomatic conditions or services for maternal and infant health [9,10]. As concern about the management of NCDs amongst PLHIV grows, the infrastructure that has been built for the provision of ART and other HIV-care services in vertical programs may be leveraged and adapted to respond to the growing burden of NCDs, among both PLHIV and HIV-negative populations [11].

Zimbabwe has experienced a particularly high burden of HIV, but has seen recent declines in its HIV incidence [12]. Older adults compromise an increasingly large proportion of PLHIV in Zimbabwe [8]. A recent study from Zimbabwe has reported that the NCD burden amongst PLHIV is substantial, with 19.6% diagnosed with at least one NCD and 4.6% with multiple NCDs [13]. However, it is not known how this NCD burden will change over time and interactions with the evolving HIV epidemic and ART will drive changes. Detailed forecasts of the timing, scale and nature of the changing NCD burden in the coming decades are needed to help identify which services in Zimbabwe should be prioritized for rapid expansion and strengthening and for which populations. The aim of this study is to conduct model-based analyses of regional and national data to provide the first national predictions of changing age structure and NCD pattern by HIV status in Zimbabwe, a hyper-endemic HIV setting in SSA.

Methods

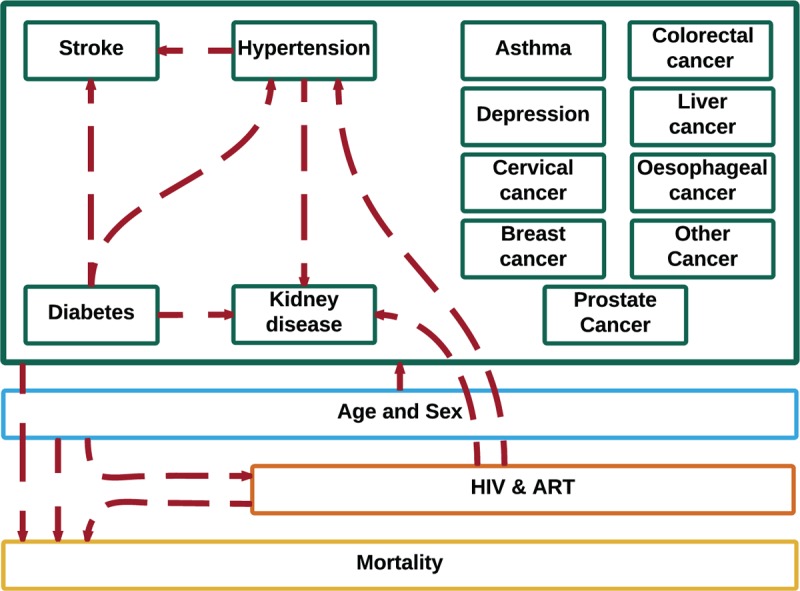

We constructed an individual-based multidisease model for Zimbabwe, coded in C++. The main model features are summarized in Fig. 1 and the full details can be found in the supplement. Briefly, the model simulates the whole population of Zimbabwe, representing age, sex, births and deaths, infection with HIV and disease progression and the development of several key NCDs. The model uses data and estimates that are available for the period from 1950 to 2015, with comparative checks of model output and data carried out for this period (supplement). The model was used to quantify the relative NCD burden in 2015, and then run from 2015 to 2035 to provide detailed forecast of changing NCD burden by HIV status. The mechanisms of the model reply on ‘scheduling’ events probabilistically at the start of a person's life (e.g. their death) so that trends across the whole population recreate observed demographic, epidemiological and clinical trends (e.g. age-and-sex-specific mortality by calendar time). Events are determined probabilistically while accounting for a person's characteristics (age, sex, preexisting condition) and calendar time. For example, a male infant is more likely to die than a female infant and both are less likely to die before the age of one in 2000 compared with 1950. As the model runs forward in time and new events occur, these can influence future events or states. For example, a patient starting ART would have a reduced risk of a premature death, thus, their date of death may be re-scheduling for later in life or a patient who just developed hypertension may develop CKD later in life.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the multidisease model for Zimbabwe.

The model simulates demography (blue), HIV-infection (orange), and noncommunicable diseases (green). The model accounts for demographic and medical risk factors for HIV infection and for development of noncommunicable diseases (red arrows to individual conditions and group of conditions). The model starts in 1950 and runs until 2035, making projections from 2015 onwards. Demographic and noncommunicable disease patterns are simulated from 1950 and the HIV epidemic from 1975. From 2015, the model is used to forecast the timing and nature of noncommunicable diseases in the general population and people living with HIV.

Demographic processes in Zimbabwe were based on estimates from United Nations’ (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs [14]. Projections of demographic trends between 2015 and 2035 assume a medium variant scenario. HIV incidence rate estimates, by age, sex and over time (1970–2015) were taken from The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) official estimates for Zimbabwe, which are derived through fitting a model to available data from populations in Demographic and Health Surveys and routine HIV surveillance amongst pregnant women [15]. The process of ART scale-up, with progressively expanding eligibility criteria, was represented and calibrated to UNAIDS estimates of the numbers of PLHIV initiating ART by CD4+ cell count in Zimbabwe [15]. HIV disease progression rates and mortality rates by CD4+ cell count amongst PLHIV not on ART were taken from a study by Mangal et al.[16]. Projections assume that HIV incidence remains stable at 2015 levels and that ART coverage increases steadily to reach a level of coverage consistent with 90 : 90 : 90 targets by 2035 (81% of PLHIV on ART by 2020). Additional results for sensitivity analyses around HIV incidence and ART coverage are presented in the supplement.

The model simulates the development and diagnosis of several key NCDs: asthma, chronic kidney disease (CKD), depression, diabetes, hypertension, strokes and key cancers. The individual cancers, which were chosen based on the most prevalent non-AIDS defining cancers in Zimbabwe (as determined by 2012 GloboCan [17]), were colorectal, liver, oesophageal, breast, cervical and prostate cancer as well as ‘other’ cancer, which constitute all other cancers. The choice of NCDs was based on key NCDs likely to play an important part in future clinical care and for which sufficient data were available to make robust predictions. Parameters defining NCD development and diagnosis were defined following a literature review (Table 1) [17–19], focusing on published studies recording age-specific prevalence or incidence rates of NCD for Zimbabwe or neighbouring countries (with the assumption that neighbouring countries experience similar age-specific prevalence patterns as Zimbabwe). Where studies presented prevalence estimates, age-specific incidence rates were calculated, assuming age-specific incidence and prevalence estimates are constant over time. NCD risks were based on age and on preexisting NCDs. Treatment for NCDs was not explicitly simulated, implicitly assuming that whatever treatment is currently available would continue in the future. NCD-specific excess mortality risk was estimated by fitting the profile of cause-of-death in the model to 2013 Global Burden of Disease estimates for Zimbabwe [20]. Projections assume that patterns of underlying risk factors for NCD remain unchanged.

Table 1.

Age-specific incidence rates of noncommunicable diseases diagnoses per 100 000 person-years.

| Age groups | Setting | Reference | ||||||||||

| 19–49 | 50–59 | >60 | ||||||||||

| Asthmaa,d | 82.5 | 578.1 | 102.9 | South Africa | Negin et al., 2008 [18] | |||||||

| Depressiona,d | 204.8 | 475.3 | 62.9 | South Africa | Negin et al., 2008 [18] | |||||||

| Diabetesa,d | 64.4 | 836.6 | 169.5 | South Africa | Negin et al., 2008 [18] | |||||||

| Hypertensiona,d | 1533.1 | 6005.9 | 1101.3 | South Africa | Negin et al., 2008 [18] | |||||||

| Strokea,d | 30.0 | 358.6 | 83.0 | South Africa | Negin et al., 2008 [18] | |||||||

| 19–39 | 40–59 | >60 | ||||||||||

| Kidney diseasea,b | 361.9 | 42.3 | 210.5 | Tanzania | Stanifer et al. 2014 [19] | |||||||

| 0–14 | 15–39 | 40–44 | 45–49 | 50–54 | 55–59 | 60–64 | 65–69 | 70–74 | >75 | |||

| Breast cancerc | 0.0 | 5.0 | 42.6 | 59.6 | 80.2 | 98.5 | 108.8 | 116.0 | 119.9 | 118.0 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

| Cervical cancerc | 0.0 | 8.3 | 71.2 | 105.8 | 136.3 | 166.0 | 220.5 | 263.3 | 299.1 | 328.1 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

| Colorectal cancerc | 0.0 | 0.7 | 4.7 | 9.8 | 17.5 | 25.0 | 36.1 | 50.0 | 63.3 | 76.9 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

| Liver cancerc | 0.3 | 1.1 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 9.6 | 13.7 | 20.8 | 34.4 | 53.8 | 80.6 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

| Oesophagus cancerc | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 5.4 | 13.7 | 25.7 | 35.7 | 46.5 | 84.2 | 141.1 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

| Prostate cancerc | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 17.2 | 96.6 | 237.7 | 470.7 | 795.3 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

| Other cancersc | 10.9 | 43.5 | 132.6 | 152.1 | 170.0 | 189.6 | 282.7 | 442.2 | 530.9 | 678.4 | Zimbabwe | GloboCan [17] |

aCalculated from reported age-specific prevalence rates.

bDefined as estimated glomerular filtration rate 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or less using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation and/or persistent albuminuria [19].

cDefined using a number of data sources and methods, including regional incidence data and mortality data [17].

dDefined using self-report of NCD diagnosis based on ‘ever having had,’ validated against a diagnosis algorithm and symptoms questions [18].

The association of one NCD to increase the risk for development of another – for example, for hypertension to increase the risk of having a stroke – was incorporated in the model following a literature review including studies from all regions (Table 2) [6,21,22]. These links are illustrated by the red arrow in Fig. 1. The increased risk for PLHIV to develop certain NCDs was incorporated into the model through parameters based on a large study from The Netherlands that compares NCD risk amongst PLHIV and matched uninfected controls [23]. The study suggested that, amongst the NCDs included in our study, the prevalence of hypertension (45.4 versus 30.5%) and CKD (4.3% versus 2.1%) was significantly higher in PLHIV than age-matched uninfected controls, likely because of factors including immune suppression, systemic inflammation and innate immune activation [23].

Table 2.

Association between risk of an individual developing a new disorder, in view of current disorder.

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Source | Setting | |

| Stroke given preexisting diabetes vs. stroke with no preexisting diabetes. | 2.31 (1.83–2.92) | Worm et al. [21] | Europe, Argentina, Australia, USA |

| Stroke given preexisting hypertension vs. stroke with no preexisting hypertension | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | Worm et al. [21] | Europe, Argentina, Australia, USA |

| Hypertension given preexisting diabetes vs. hypertension with no preexisting diabetes | 1.40 (1.19–1.64) | Smit et al. [6] | The Netherlands |

| Kidney disease given preexisting diabetes vs. kidney disease with no preexisting diabetes | 1.50 (1.05–2.15) | Mocroft et al. [22] | Europe, Argentina and Israel |

| Kidney disease given preexisting hypertension vs. kidney disease with no preexisting hypertension | 1.69 (1.26–2.27) | Mocroft et al. [22] | Europe, Argentina and Israel |

Wherever patients had two or more NCDs that could affect the development of another NCD, we calculated parameters as the mean of the largest factor and the product of the factors. CI, confidence intervals; NCDS, noncommunicable diseases.

Results

Demographic patterns

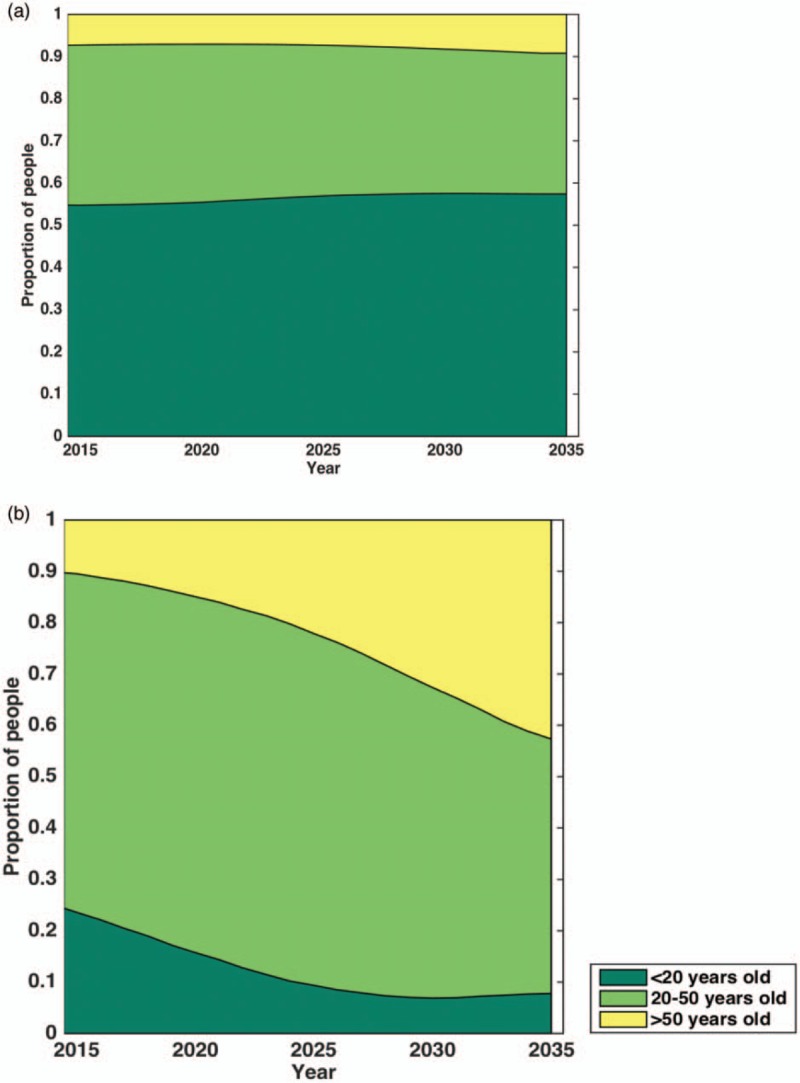

The UN demographic projections lead to a forecast of the population of Zimbabwe growing from 15.5 million in 2015 to 23.5 million people by 2035. The model indicated that the population of PLHIV is expected to decrease in the same time period, from 1.2 million to 1 million, assuming levels of HIV incidence remain constant. Although the age-structure of the whole population is projected to remain relatively stable (mean age 20 in 2015 and 26 in 2035); Fig. 2a), the mean age of PLHIV in 2015 will rise rapidly, from 31 years in 2015 to 45 years by 2035 (Fig. 2b). This increase in mean age is driven by the recent drop in HIV incidence and ART extending life-expectancy of PLHIV on ART. The model predicts that had ART not been introduced in Zimbabwe in 2004, mean age of PLHIV would be 34 by 2035, whereas if HIV incidence had remained at 1990s levels (highest incidence level), mean age would be 31.

Fig. 2.

Projected age distribution in Zimbabwe of the (a) general population (includes people living with HIV and uninfected persons) and (b) people living with HIV between 2015 and 2035.

Patterns of comorbidity in Zimbabwe

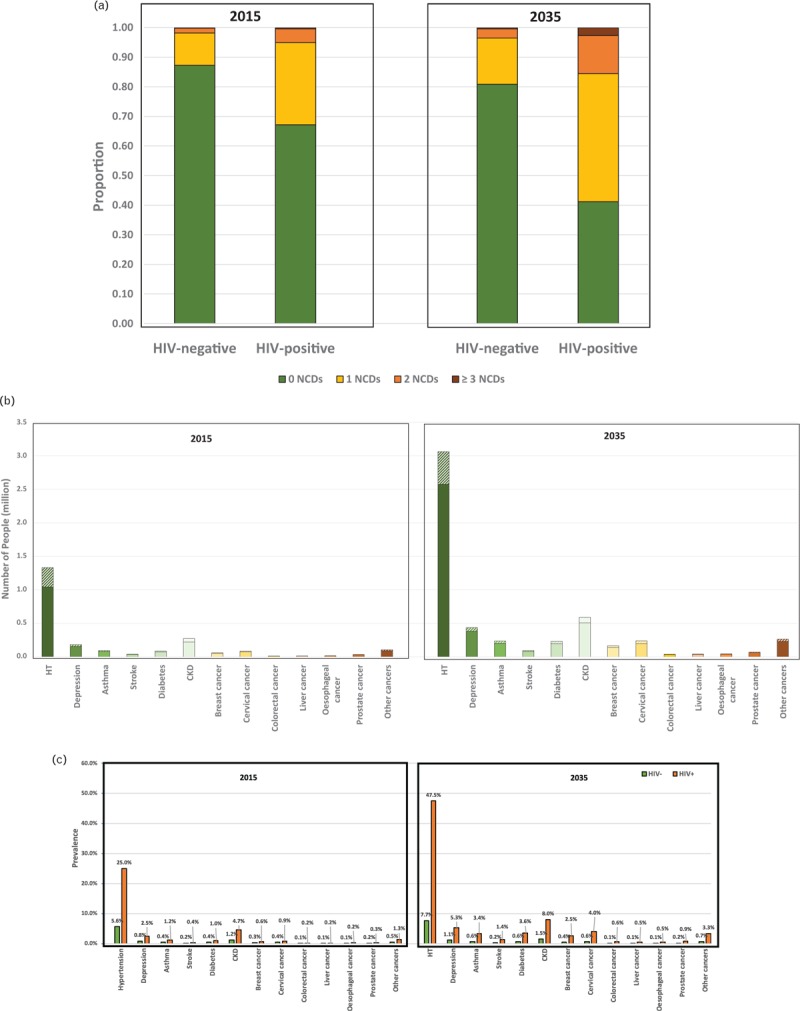

PLHIV are more likely to be diagnosed with single or multiple morbidities in 2015 compared with uninfected persons (Fig. 3 a). An estimated 14% of HIV-negative persons are diagnosed with at least one key NCD in 2015, compared with 33% of PLHIV, reflecting the differing age structure in the two groups and the greater propensity of PLHIV to develop certain NCDs. However, even if PLHIV experienced no additional NCD risk relating to HIV and ART, 26% would suffer from one or more key NCDs simply because of their older average age. Modelled, age-standardized incidence rates per person suggest that the majority of these patterns will be driven by age (0.22 and 0.23 in uninfected adults versus 0.2 and 0.24 in adult PLHIV in 2015 and 2035, respectively), rather than cumulative exposure to HIV and ART.

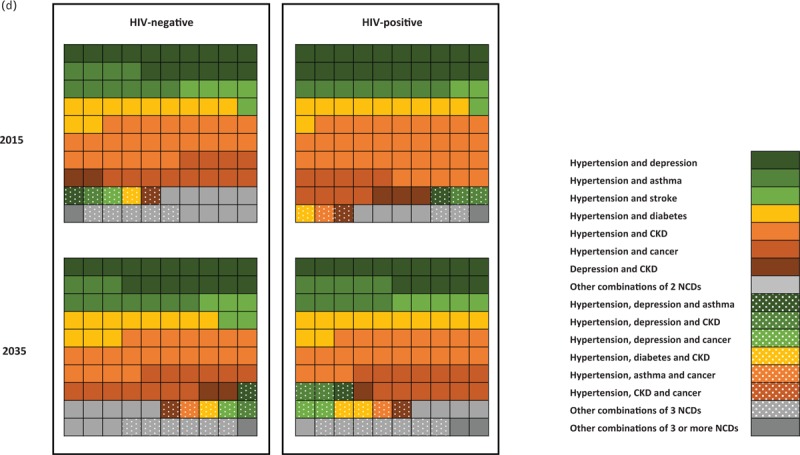

Fig. 3.

Projections of noncommunicable disease burden.

(a) Proportion of people with 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more NCDs in 2015 and 2035 by HIV status. (b) Number of people diagnosed with specific NCDs by HIV status in 2015 and 2035. (c) Prevalence of specific NCDs by HIV status in 2015 and 2035. Solid colours refer to HIV-negative and shaded area to people living with HIV. (d) Multidisease profile by HIV status amongst people with at least two NCDs in 2015 and 2035. Plain areas refer to two NCD combinations and dotted areas refers to three NCD combinations. Results shown as a cross-section of the population with each square representing one patient. HT, hypertension; stroke, refers to ever having had a stroke; CKD, chronic kidney disease; other cancers include all cancers other than breast, cervical, colorectal, liver, oesophageal, and prostate cancer.

Fig. 3 (Continued).

Projections of noncommunicable disease burden.

(a) Proportion of people with 0, 1, 2, and 3 or more NCDs in 2015 and 2035 by HIV status. (b) Number of people diagnosed with specific NCDs by HIV status in 2015 and 2035. (c) Prevalence of specific NCDs by HIV status in 2015 and 2035. Solid colours refer to HIV-negative and shaded area to people living with HIV. (d) Multidisease profile by HIV status amongst people with at least two NCDs in 2015 and 2035. Plain areas refer to two NCD combinations and dotted areas refers to three NCD combinations. Results shown as a cross-section of the population with each square representing one patient. HT, hypertension; stroke, refers to ever having had a stroke; CKD, chronic kidney disease; other cancers include all cancers other than breast, cervical, colorectal, liver, oesophageal, and prostate cancer.

This difference in multimorbidity NCD prevalence by HIV status is forecast to become more pronounced over the coming 20 years. The proportion of PLHIV diagnosed with at least one key NCD is projected to increase from 33% in 2015 to 59% in 2035, and proportion diagnosed with two or more from 5% in 2015 to 16% in 2035 (Fig. 3 a). In the absence of additional NCD risk because of HIV infection, fewer (36%) would be expected to be diagnosed with at least one NCD. This contrasts with projected key NCD prevalence among HIV-negative, with 21% diagnosed with at least one NCD in 2035.

Amongst the NCDs evaluated by this model, the most prevalent NCDs between 2015 and 2035 are hypertension, CKD, depression and ever having been diagnosed with (any) cancer. Prevalence in 2015 is higher amongst PLHIV compared with uninfected persons and will increase steeply by 2035 compared with uninfected persons (Fig. 3 c; for example, 25% of PLHIV are diagnosed with hypertension vs. 5.6% of uninfected persons in 2015 and 47.5% vs. 7.7% in 2035, 4.7% of PLHIV with CKD vs. 1.2% of uninfected persons in 2015 and 8% vs. 1.5% in 2035; Fig. 3 c). The most prevalent cancers are cervical cancer (0.6% in 2015 vs. 0.8% in 2035) and breast cancer (0.4% in 2015 vs. 0.8% in 2035 in all people). As hypertension is a risk factor for other NCDs, including serious cardiovascular outcomes (i.e. strokes) and CKD, this increase contributes to escalating numbers of persons with multiple comorbidities. Age-standardized incidence rates per person suggest that the majority of these patterns will be driven by age (e.g. 0.16 and 0.16 in uninfected adults versus 0.21 and 0.16 in adult PLHIV in 2015 and 2035, respectively, for hypertension).

Although there is a predicted growth in prevalence of NCDs amongst PLHIV, most cases of NCDs will still be amongst HIV-negative persons (consistent with the fact that most people in the population are HIV-negative) and the total number of persons in Zimbabwe diagnosed with NCDs will nearly double or more in the coming 20 years (Fig. 3 b). The number of people diagnosed with hypertension will increase from 1.33 million [1.04 million (78%) HIV-negative and 0.29 million (22%) PLHIV] in 2015 to 3.06 million [2.57 million (84%) HIV-negative and 0.49 million (16%) PLHIV]. Other than hypertension, the NCDs which affect the greatest number of people are CKD, increasing from 0.27 million in 2015 [0.22 million (80%) HIV-negative and 0.05 million (20%) PLHIV] to 0.59 million in 2035 [0.51 million (86%) HIV-negative and 0.08 million (14%) PLHIV] and depression 0.18 million in 2015 [0.15 million (85%) HIV-negative and 0.03 million (15%) PLHIV] to 0.44 million in 2035 (0.38 million (88%) HIV-negative and 0.05 million (12%) PLHIV].

Amongst people with at least two NCDs, a majority will suffer from hypertension with either CKD (21.2%), depression (16.6%), cancer (12.8%), diabetes (11.5%), asthma (10.0%) or stroke (4.7%; Fig. 3 d), with trends similar by HIV status. Notable differences by HIV status include that, although the major contributing multimorbidity profiles amongst HIV-uninfected are composed of two NCDs, amongst PLHIV, a large proportion consist of three NCDs. These include hypertension and CKD with either depression (2.1% in 2015 and 2.3% in 2035), diabetes (0.7% in 2015 and 1.6% in 2035), cancer (0.5% in 2015 and 1.4% in 2035), or hypertension with depression and cancer (0.2% in 2015 and 1.5% in 2035; Fig. 3 d).

Discussion

Without changes in underlying risk factors, the burden of key NCDs in Zimbabwe is set to increase steeply in the coming 20 years, particularly in PLHIV. This will have major implications for healthcare provisions, requiring substantial planning for additional services. The increase in NCD burden will be driven by population growth, and amongst PLHIV by the rapidly ageing population of PLHIV (because of reductions in incidence and the success of ART scale-up) and, to a lesser extent, the cumulative exposure to HIV and ART. Our results suggest that by 2035, adult PLHIV will be nearly twice as likely to suffer from at least one key NCD and three times more likely to suffer from multiple key NCDs compared with HIV-negative persons, and that 15.2% of all key NCDs will be diagnosed in PLHIV, although they will contribute only 5.0% of the total Zimbabwean population.

The changing patterns of disease burden will exert increasing pressure on already fragile health systems in the country at all levels of care [24]. Given resource constraints, the identification of cost-effective chronic disease service delivery models to manage the dual burden of HIV and NCDs will be critical to maintain the quality of health services in the country. In particular, there is a need to expand and strengthen the screening and treatment of hypertension, CKD, depression and cancers, as well as for prevention campaigns to be intensified. At the same time, the need to manage infectious diseases including tuberculosis, malaria and schistosomiasis (which also interact with HIV [25–27]), will remain in Zimbabwe for many years [28]. Existing vertical infectious disease programmes potentially offer a platform to expand NCD services, but may be over-burdened. Service integration has the potential to both reduce costs (for providers and patients) associated with multiple visits and improve the quality of care – if carefully designed and sufficiently resourced, as to not damage existing health gains. Further research is needed to identify the feasibility of integrating additional services – for PLHIV and uninfected persons – into existing services and guide aspects such as monitoring and evaluation systems, targeted behavioural changes, demand generation for preventive services and linkage to care [29], in a way that strengthens rather than depletes current human resource capacity in the health sector.

Some important changes are already underway that may facilitate these efforts. HIV programs are shifting from vertical programs, focused on HIV diagnosis and treatment, to integrated care management, incorporating testing and treatment for other conditions and exploring community-based delivery [30]. Recent World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines have promoted integrated and differentiated care, which increasingly seeks to minimise the requirement of PLHIV that are stably virally suppressed to attend clinics [31]. As the PLHIV population ages, new protocols should carefully consider the extent to which patients with NCDs should have differential care, and balance the benefits of reduced treatment monitoring intensity against the benefits of risk group identification, screening and management of NCDs among PLHIV [31].

Our 2015 estimates are qualitatively similar to those reported in the 2015 cross-sectional study by Magodoro et al.[13]. This study found a large burden of single (19.6%) and multiple (4.6%) morbidity amongst their study population of PLHIV, and that hypertension (10%), diabetes (2.1%), asthma (4.3%) and cancers (1.8%) contributed a large burden of NCD. Differences observed between their results and ours (e.g. single morbidity 19.6 vs. 28%, hypertension prevalence of 10 vs. 25%, asthma prevalence of 4.3 vs. 1.2%, diabetes prevalence of 2.1 vs. 1% and cancer prevalence 1.8 vs. 2.5% in their study compared with ours) may be in part because of the range of NCDs investigated, differences in NCD definitions, inclusion criteria for study participants and method used by Magodoro et al.[13], who reviewed patients’ records for self-reported NCDs rather than clinical diagnosis.

This is the first model to forecast NCD burden in a low–middle-income setting with high HIV burden, with a focus on the burden amongst PLHIV in particular and to show how this is driven by clinical interactions, the evolving HIV epidemiology and maturing ART program. Our results are likely to be relevant for other HIV hyperendemic settings in Africa, which are undergoing rapid expansion of ART programs. Although further data collection and analysis on NCD trends in all countries is required, the results of this study provide an initial insight into the future NCD burden in a SSA country with a high HIV prevalence.

Despite these strengths, the model is limited by sparse data availability for age-specific NCD incidence or prevalence estimates in Zimbabwe. This restricts the extent to which the output could be tested and validated and may translate into conservative estimate of future NCD burden to the extent to which specific NCDs are not included. A major assumption of this study is that age-specific prevalence estimates in Zimbabwe will be similar to those reported in neighbouring countries, including South Africa, and that the increased likelihood for an individual to develop an NCD based on preexisting history of HIV or another NCD are translatable from high-income settings. The mechanisms driving increased NCD risk amongst PLHIV are complex and the relative contribution of various risk factors for NCDs in PLHIV is a topic of ongoing research. The model aims to capture the key factors relating to the HIV epidemic and attempts to incorporate the interdependence of NCDs and HIV in a manner consistent with best current understandings, but inevitably many layers of clinical interaction are not captured. For example, the model accounts for overall HIV-related risk for NCDs (e.g. related to inflammation of antiretroviral use), but in the absence of robust projections on how antiretroviral usage may change over time, we do not include the impact of individual antiretrovirals on NCDs [32]. Similarly, the model does not account for potential changes in healthcare access (other than 90 : 90 : 90 scale-up) or structural changes, which may impact both NCD and HIV burden, for example, integrating screening and treatment services for NCDs in HIV clinics may reduce NCD burden. Most research output come from high-income settings [32], and although we have used those insights here, the extent to which those interactions will pertain to the Zimbabwean populations remains unclear. We hope that these analyses will catalyse further data collection and reporting, and as more data on age-specific NCD prevalence and risk factors for NCDs emerge from Zimbabwe, the model output can be updated.

The model does not account for changes in survival rates with NCDs, and does not simulate all NCDs that can affect the population of Zimbabwe. Nor does the model simulate communicable diseases and how increases in life expectancy could affect these or how reduction in fear of HVI transmission could increase risk behaviour and consequently, sexually transmitted diseases. However, the model does model all cancers, including AIDS-defining cancers, which may result in an underestimation of the proportion of cancers in HIV-positive compared with HIV-negative people. Furthermore, NCD data is based on diagnosed cases, and thus is likely to underestimate the true burden by excluding undiagnosed cases. These factors would tend to make the results a conservative estimate of the true NCD burden affecting Zimbabwe in the next 20 years. The model does not incorporate a transmission model, but rather simulates infection with HIV using incidence estimates [15]. Consequently, there is no dynamic feedback between processes in this model and those HIV incidence projections.

Because of the lack of detailed data on lifestyle factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and exercise and lack of robust projections on how these factors may change in the coming 20 years, the model assumes that the effect of lifestyle factors is uniform across the population and constant over time. If lifestyle-related risk factors are really restricted to a small proportion of the population in Zimbabwe, the model results may be overestimating or underestimating the number of people suffering from one or more NCD (overestimate in relation to smoking and alcohol consumption and underestimate in the case of healthy diet and exercise). As new data becomes available, the model results can be updated.

The profile of the PLHIV in Zimbabwe, and elsewhere in Africa, is changing, presenting new challenges in terms of meeting their healthcare needs. Failing to adapt could lead to deteriorating outcomes for PLHIV and further strain fragile health systems. Existing vertical HIV programs may provide opportunity for new NCD screening services for PLHIV and an example for uninfected persons. A priority for health systems research in the coming years must be to establish how these many competing priorities can be managed effectively with the limited resources that are available to them.

Acknowledgements

J.O. assisted with the model construction and code writing. A.V., N.P.F. and M.V. advised on all the healthcare system aspect of the interpretation of the output of this work. S.G. advised on HIV and NCD program aspects within Zimbabwe relating to the interpretation of the results. T.B.H. and M.S. conceptualized the study. M.S. developed the model, and carried out the analyses.

Funding: The study was funded by the Rush Foundation and the NIH (R21AG053093–02).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva, Switzerland; 2016. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/global-AIDS-update-2016_en.pdf [Accessed 22 October 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. The Gap report - 2014; 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf [Accessed 13 January 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills EJ, Bärnighausen T, Negin J. HIV and aging--preparing for the challenges ahead. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1270–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negin J, Bärnighausen T, Lundgren JD, Mills EJ. Aging with HIV in Africa. AIDS 2012; 26:S1–S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornell M, Johnson LF, Schomaker M, Tanser F, Maskew M, Wood R, et al. International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS-Southern Africa Collaboration. Age in antiretroviral therapy programmes in South Africa: a retrospective, multicentre, observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 2015; 2:e368–e375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smit M, Brinkman K, Geerlings S, Smit C, Thyagarajan K, van Sighem A, et al. ATHENA observational cohort. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNAIDS. The Gap report 2014 - people aged 50 years and older. Geneva, Switzerland; 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/12_Peopleaged50yearsandolder.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negin J, Gregson S, Eaton JW, Schur N, Takaruza A, Mason P, et al. Rising levels of HIV infection in older adults in Eastern Zimbabwe. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0162967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabkin M, Kruk ME, El-Sadr WM. HIV, aging and continuity care: strengthening health systems to support services for noncommunicable diseases in low-income countries. AIDS Lond Engl 2012; 26 suppl 1:S77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de-Graft Aikins A, Unwin N, Agyemang C, Allotey P, Campbell C, Arhinful D. Tackling Africa's chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Glob Health 2010; 6:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maher D, Ford N, Unwin N. Priorities for developing countries in the global response to non-communicable diseases. Glob Health 2012; 8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregson S, Gonese E, Hallett TB, Taruberekera N, Hargrove JW, Lopman B, et al. HIV decline in Zimbabwe due to reductions in risky sex? Evidence from a comprehensive epidemiological review. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39:1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magodoro IM, Esterhuizen TM, Chivese T. A cross-sectional, facility based study of comorbid non-communicable diseases among adults living with HIV infection in Zimbabwe. BMC Res Notes 2016; 9:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations. United Nations - Department of Economic and social Affairs. 2015. Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ [Accessed 1 August 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.UNAID. UNAIDS - Epidemic Projection Package. 2015. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/datatools/spectrumepp [Accessed 5 May 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangal TD. UNAIDS Working Group on CD4 Progression and Mortality Amongst HIV Seroconverters including the CASCADE Collaboration in EuroCoord. Joint estimation of CD4+ cell progression and survival in untreated individuals with HIV-1 infection. AIDS Lond Engl 2017; 31:1073–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GloboCan 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Available at: http://globocan.iarc.fr/old/age-specific_table_r.asp?selection=227716&title=Zimbabwe&sex=0&type=0&stat=0&window=1&sort=0&submit=%C2%A0Execute [Accessed 27 May 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negin J, Martiniuk A, Cumming RG, Naidoo N, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Madurai L, et al. Prevalence of HIV and chronic comorbidities among older adults. AIDS 2012; 26 suppl 1:S55–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanifer JW, Maro V, Egger J, Karia F, Thielman N, Turner EL, et al. The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in northern Tanzania: a population-based survey. PLoS ONE 2015; 10:e0124506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IHME. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation - MDG Viz. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/institute-health-metrics-and-evaluation [Accessed 20 August 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worm SW, Sabin CA, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Monforte Ad, Pradier C, et al. Presence of the metabolic syndrome is not a better predictor of cardiovascular disease than the sum of its components in HIV-infected individuals Data Collection on Adverse events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mocroft A, Kirk O, Reiss P, De Wit S, Sedlacek D, Beniowski M, et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate, chronic kidney disease and antiretroviral drug use in HIV-positive patients. AIDS 2010; 24:1667–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, Kootstra N, van der Valk M, Geerlings SG, et al. AGEhIV Cohort Study Group. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2014; 59:1787–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Todd C, Ray S, Madzimbamuto F, Sanders D. What is the way forward for health in Zimbabwe?. Lancet 2010; 375:606–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Badri M, Ehrlich R, Wood R, Pulerwitz T, Maartens G. Association between tuberculosis and HIV disease progression in a high tuberculosis prevalence area. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis Off J Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis 2001; 5:225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kallestrup P, Zinyama R, Gomo E, Butterworth AE, Mudenge B, van Dam GJ, et al. Schistosomiasis and HIV-1 infection in rural Zimbabwe: effect of treatment of schistosomiasis on CD4 cell count and plasma HIV-1 RNA load. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:1956–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abu-Raddad LJ, Patnaik P, Kublin JG. Dual infection with HIV and malaria fuels the spread of both diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Available at: http://www.sciencemag.org [Accessed 17 February 2015]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.African Health Observatory, World Health Organisation. Comprehensive Analytical Profile: Zimbabwe. Available at: http://www.aho.afro.who.int/profiles_information/index.php/Zimbabwe:Index?lang=en [Accessed 1 October 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rachlis B, Naanyu V, Wachira J, Genberg B, Koech B, Kamene R, et al. Identifying common barriers and facilitators to linkage and retention in chronic disease care in western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2016; 16:741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rachlis B, Naanyu V, Wachira J, Genberg B, Koech B, Kamene R, et al. Community perceptions of community health workers (CHWs) and their roles in management for HIV, tuberculosis and hypertension in Western Kenya. PloS One 2016; 11:e0149412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organisation. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva, Switzerland; 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/ [Accessed 1 October 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Althoff KN, Smit M, Reiss P, Justice AC. HIV and ageing: improving quantity and quality of life. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016; 11:527–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.