Abstract

Eagle syndrome is caused by an elongated styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament. The stylocarotid variant with neurologic symptoms is rare and presents a diagnostic challenge. Patients may present with transient ischemic attacks, syncope, or less well defined symptoms like episodic dizziness. We report use of vascular laboratory testing in the management of Eagle syndrome. In one patient, on Doppler ultrasound examination of the ipsilateral temporal artery, the signal was lost with provocative neck flexion. In another patient, transcranial Doppler ultrasound showed blunting of the middle cerebral artery with provocative maneuvers. We used perioperative transcranial Doppler ultrasound to assess the effectiveness of styloid resection.

In 1937, Dr Watt Eagle reported two cases of elongated styloid process causing a cervical pain syndrome. He described the normal styloid process as between 2.5 and 3 cm.1 He later described two syndromes associated with an elongated styloid process or abnormally ossified stylohyoid ligament. The first and more common is now referred to as stylohyoid syndrome. It is typically regarded as a pain syndrome presenting with neck, throat, or ear pain. The second has symptoms related to the internal or external carotid arteries, as the elongated styloid process crosses anterolateral to the internal carotid artery (ICA) and posteromedial to the external carotid artery and may compress with either medial or lateral deviation. He designated it the styloid process-carotid artery syndrome.2 It is now known as stylocarotid or stylocarotid artery syndrome. There are reports of stylocarotid syndrome including but not limited to ICA dissection with focal neurologic deficits,3, 4 recurrent transient ischemic attacks,5 and even carotid artery stent fractures.6 Patients may also have presyncopal or syncopal events with neck turning.

Stylocarotid artery syndrome symptoms may be vague, and most patients with a radiographically elongated or abnormal stylohyoid apparatus are asymptomatic,7 resulting in low awareness of physicians. We describe two patients with stylocarotid syndrome, with particular attention to the use of transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound in the confirmation of the diagnosis and treatment. Written consent was obtained from both patients.

Case reports

Case 1

A 65-year-old woman presented with 12 years of headache, neck pain, and reproducible near-syncope with neck flexion and arm elevation. Between 2005 and 2015, she underwent >60 diagnostic studies at several facilities without a conclusive diagnosis. These included 10 series of plain films of the cervical spine, 9 computed tomography (CT) scans of the cervical spine, 2 CT angiography (CTA) scans of the cervical spine, 6 other CT scans including 1 CTA scan of the head, 4 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the cervical spine, 4 brain MRI scans, 2 magnetic resonance angiography scans of the neck, 3 CTA scans of the chest, and 2 cerebral angiography scans. She had multiple TCD ultrasound examinations without her specific provocative maneuvers.

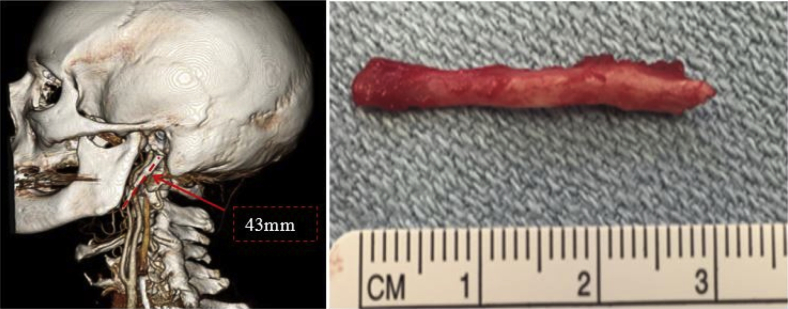

She made lifestyle modifications to avoid head turning, including use of a complex set of mirrors and cameras to drive. On referral, review of her imaging revealed a 43-mm left styloid process (Fig 1, left). In addition to reproducing symptoms, we found loss of temporal artery Doppler signal with neck flexion on physical examination. She had resection of her left styloid process (Fig 1, right) and experienced immediate resolution of symptoms and had maintained temporal artery Doppler signal with neck flexion.

Fig 1.

Case 1. Left, Preoperative computed tomography (CT) reconstruction showing 43-mm styloid process. Right, Excised styloid process.

Case 2

A 56-year-old woman presented with 9 years of near-syncopal events, seizure-like movements, and visual changes with provocative neck positioning. Her symptoms were understandably concerning and resulted in extensive cardiac and neurologic evaluations before her referral to our institution. These included echocardiography, carotid artery duplex ultrasound, exercise stress test, Holter monitoring, electroencephalography, brain MRI, carotid magnetic resonance angiography, and contrast-enhanced neck CT, the findings of all of which were reported as normal. In addition, she had a carotid massage study, which was positive for hypersensitive baroreceptor response, as well as a tilt-table test that had a positive result with a trigger of isoproterenol. She was diagnosed with vagal-mediated loss of consciousness. She also adapted to avoid the provocative maneuvers that brought on her symptoms.

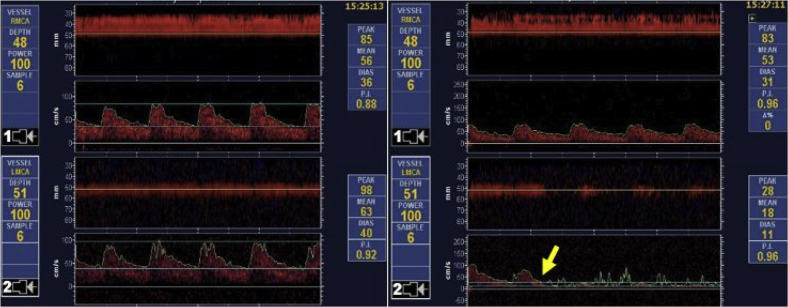

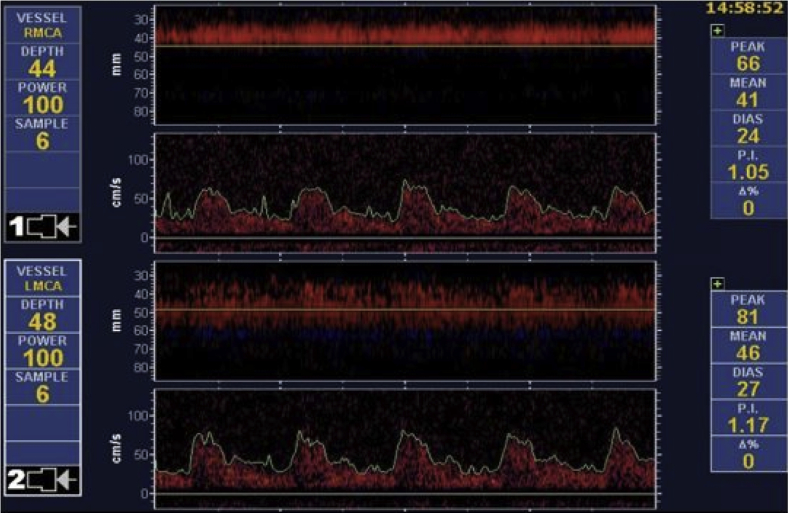

Imaging review revealed an abnormal stylohyoid apparatus (Fig 2, left). After repeated carotid duplex ultrasound suggested impingement of the ICA with provocative measures, she had TCD ultrasound with provocative maneuvers. This showed definitive blunting of her left middle cerebral artery (MCA) flow waveform (Fig 3) with concurrent symptoms of syncope. She had excision of her calcified stylohyoid ligament (Fig 2, right) with intraoperative confirmation of normalized MCA waveforms with provocative maneuvers. She was immediately asymptomatic, and postoperative awake TCD ultrasound examination with provocative measures showed no MCA waveform changes (Fig 4).

Fig 2.

Case 2. Left, Preoperative computed tomography (CT) reconstruction showing 54-mm styloid process. Right, Excised styloid process.

Fig 3.

Case 2. Left, Preoperative transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound of middle cerebral artery (MCA) in neutral head position showing a normal waveform. Right, Preoperative TCD ultrasound of MCA with head turned left (yellow arrow) showing blunting of left MCA waveform.

Fig 4.

Case 2. Postoperative transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound of middle cerebral artery (MCA) with head turned left, showing maintenance of a normal waveform.

Discussion

The reported incidence of an abnormal stylohyoid complex ranges from 4% to 28%,2, 8 occurring mostly between the fourth and sixth decades with a 3:1 female predominance.9 Correll et al10 reported an incidence of 18.2% in a Veterans Administration-based study reviewing 1771 radiographs. Whereas the incidence of the radiographic finding might be debated, the clinical presentation remains rare, and many vascular surgeons have not heard of the syndrome. The implication is that patients often endure their symptoms for a long time before diagnosis and definitive treatment.

In addition to Dr Eagle's description of normal styloid lengths of 2.5 to 3 cm, there are varying descriptions of normal. Whereas many seem to accept 3 cm, Moffat et al11 found mean values between 1.52 and 4.77 cm in cadaver studies, and Monsour and Young12 suggested 4 cm as the upper limit of normal. The average length of styloid in Eagle syndrome is reported by Balcioglu et al13 as 40 ± 4.72 mm, but there have been symptoms reported as low as 3.2 cm. Thus, we believe 3 cm is reasonable as an upper definition of normal. However, because the incidence of symptoms with elongated styloid processes is only 4%,14 abnormal should be put in context of the presence of symptoms and confirmatory studies. Moreover, elongated styloid processes do not seem to be significant in the absence of symptoms. As far as vascular symptoms are concerned, cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack from thromboembolism or dissection and stent fractures from compression are intuitive. However, syncope is less intuitive, given the brain's robust collateralization. Our patient had minimal flow in bilateral P1 segments on TCD ultrasound examination, consistent with either atretic or fetal origin posterior cerebral artery. Our speculation is that a disruption in the circle of Willis is likely to be necessary for syncope to occur in stylocarotid syndrome.

When stylocarotid syndrome is suspected on clinical grounds, although carotid duplex ultrasound may be used to screen for velocity abnormalities, we note the technical difficulty associated with evaluating the distal ICA at the zone of compression. The patient in case 1 had multiple nondiagnostic carotid artery duplex ultrasound studies with provocative maneuvers. Whereas the patient in case 2 did have duplex ultrasound findings suggestive of impingement, it cannot show that collateral circulation has not compensated distally. With symptoms related to thromboembolism or dissection, it would be reasonable to accept a diagnostic carotid artery duplex ultrasound examination. However, it cannot prove the lesion as the culprit behind symptoms of syncope. Our recommended workup is carotid artery duplex ultrasound with neutral and provocative positioning, CTA of the neck in neutral position to identify an elongated styloid process and to assess the distal artery for injury, and TCD ultrasound in neutral and provocative positions for confirmation of distal effect, especially if syncope is the presenting symptom.

Whereas Dr Eagle initially described a transoral approach, excision is now most often done through an external approach for improved visualization, with minimal complications.15, 16 At our institution, stylocarotid syndrome is managed by vascular and ear, nose, and throat surgeons together, through an external approach. An incision is made at the inferior border of the submandibular gland. The inferior aspect of the gland is identified and bluntly dissected from the digastric muscle. The contents of the submandibular triangle are retracted superiorly, and the styloid process can then be palpated in the fossa. The facial artery may be encountered and ligated or preserved. The lingual nerve is identified and preserved anteriorly. The styloid process is bluntly cleaned until the bone is exposed circumferentially and grasped proximally near the skull base and fractured with a rongeur. We do not routinely explore or reconstruct the carotid arteries. Although there are rare reports of associated carotid artery false or true aneurysms,17, 18 there are no reports to suggest need for routine arterial reconstruction otherwise.

Conclusions

Eagle syndrome, specifically the stylocarotid variant, is rare, and diagnosis is often delayed. TCD ultrasound with provocative maneuvers can be a useful adjunct for confirming this diagnosis and obviating the need for extensive studies. It can also be used as a tool for confirmation of successful treatment.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Dr Albert L. Merati of the University of Washington Department of Otolaryngology.

From the Society for Vascular Surgery

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Eagle W.W. Elongated styloid processes: report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1937;25:584–587. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagle W.W. Symptomatic elongated styloid process: report of two cases of styloid process-carotid artery syndrome with operation. Arch Otolaryngol. 1949;49:490–503. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760110046003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sveinsson O., Kostulas N., Herrman L. Internal carotid dissection caused by an elongated styloid process (Eagle syndrome) BMJ Case Rep. 2013 Jun 11;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-009878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smoot T.W., Taha A., Tarlov N., Riebe B. Eagle syndrome: a case report of stylocarotid syndrome with internal carotid artery dissection. Interv Neuroradiol. 2017;23:433–436. doi: 10.1177/1591019917706050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David J., Lieb M., Rahimi S.A. Stylocarotid artery syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1661–1663. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooker J.D., Joyner D.A., Farley D.P., Khan M. Carotid stent fracture from stylocarotid syndrome. J Radiol Case Rep. 2016;10:1–8. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v10i6.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keur J.J., Campbell J.P., McCarthy J.F., Ralph W.J. The clinical significance of the elongated styloid process. Oral Surg. 1986;61:399–404. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaufman S.M., Elzay R.P., Irish E.F. Styloid process variation. Radiologic and clinical study. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;91:460–463. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.00770040654013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilguy M., Ilguy D., Guler N., Bayirli G. Incidence of the type and calcification patterns in patients with elongated styloid process. J Int Med Res. 2005;33:96–102. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correll R.W., Jensen J.L., Taylor J.B., Rhyne R.R. Mineralization of the stylohyoid- stylomandibular ligament complex. Oral Surg. 1979;48:286–291. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffat D.A., Ramsden R.T., Shaw H.J. The styloid process syndrome; aetiological factors and surgical management. J Laryngol Otol. 1977;91:279–294. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100083699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monsour P.A., Young W.G. Variability of the styloid process and stylohyoid ligament in panoramic radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:522–526. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balcioglu H.A., Kilic C., Akyol M., Ozan H., Kokten G. Length of the styloid process and anatomical implications for Eagle’s syndrome. Folia Morphol. 2009;68:265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eagle W.W. Elongated styloid process: further observation and a new syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:630–640. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1948.00690030654006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badhey A., Jategaonkar A., Anglin Kovacs A.J., Kadakia S., De Deyn P.P., Ducic Y. Eagle syndrome: a comprehensive review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;159:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ceylan A., Koybasioglu A., Celenk F., Yilmaz O., Uslu S. Surgical treatment of elongated styloid process: experience of 61 cases. Skull Base. 2008;18:289–295. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1086057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dao A., Karnezis S., Lane J.S., III, Fujitani R.M., Saremi F. Eagle syndrome presenting with external carotid artery pseudoaneurysm. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18:263–265. doi: 10.1007/s10140-010-0930-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamade YJ, Medicherla CB, Zammar SG, Aoun RJ, Nanney AD 3rd, Hoel AW, et al. Microsurgical management of Eagle syndrome with ipsilateral carotid-ophthalmic aneurysm: 3-dimensional operative video [published online ahead of print August 27, 2015]. Neurosurgery doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000990. [DOI] [PubMed]