Abstract

The aim of the present study was to provide insight into various demographic, clinical, and management profile of Indian patients with oral tongue squamous cell cancer (OTSCC). All the OTSCC patients who had undergone surgical treatment during 1995 to 2010 at a tertiary care center in North India were considered for the present study. The details of the patients were retrieved from a prospectively maintained computerized database. A total of 124 patients were included in the present study. Mean age of the patients was 50.4 ± 12.0 years. Lateral border of the tongue was the most common sub-site involved in 110 (88.7%) patients. Neck nodes were clinically palpable in 56.4% patients. Hemiglossectomy and anterior partial glossectomy were common surgical procedure undertaken in 57.2 and 25.8% patients. Negative resection margin was achieved in 97.5% patients. Pathological neck metastasis was seen in 40.3% patients. Occult neck metastasis was present in 25.9% patients among clinical N0 neck. At a mean follow-up of 29.8 months (SD 3.1), 20.1% developed disease relapse and 4.0% patients developed second primaries. Kaplan-Meier analysis estimated a 5-year disease-free survival of 81.5% and a 5 years overall survival of 78.6%. Cox proportional regression analysis predicted tumor size and number of positive nodes to be independent predictive variables for disease recurrence. Quality controlled surgery, coupled with adjuvant treatment when required, provides a safe and effective treatment of OTSCC with a good disease-free survival and loco-regional control.

Keywords: Oral neoplasms, Tongue neoplasms, Glossectomy, Radiotherapy, Chemotherapy, Survival analysis

Introduction

Oral cancer incorporates a heterogeneous group of cancers which arise at different sub-sites of oral cavity. As per GLOBOCAN 2012 data (project of International Agency for Research on Cancer), oral cavity cancer (including lip) is one of the three common cancers in India with an annual incidence of 7.6% and 5-year prevalence of 6.6% [1]. Oral cancer is the fifth common cause of cancer-related death (7.6%) in India underscoring the magnitude of problem. Though tongue is the most common site of oral cavity cancer worldwide, it is second to the buccal mucosa and gingivo-buccal sulcus in most of the Indian studies due to widespread tobacco consumption including betel quid [2]. Though oral cavity cancer is the disease of developing countries, the overwhelming majority of the concerned publications come from the developed countries. Moreover, majority of the authors usually amalgamate cancers of all sub-sites of head and neck providing a heterogeneous representation. Expectedly, most of the oral cavity cancer treatment guidelines are based on western literature. These guidelines fail to address the problems of patients being managed in developing countries because of wide variations in epidemiology, demography, clinical profile, treatment patterns, and risk factors of oral cavity cancer. This underscores the urgent need to create an effective clinical database of cancer patients in developing world [3]. The aim of the present study was to provide insight into various demographic, clinical, and management profile of Indian patients with operable oral tongue squamous cell cancer (OTSCC).

Methods

A retrospective analysis of the prospectively maintained computerized database of the patients was done to retrieve the details of all the OTSCC patients who had undergone surgical treatment during 1995 to 2010. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Human Research. The patients were included if they were aged more than 18 years and were found to have pathologically proven squamous cell carcinoma. Those patients who had undergone primary surgery in a different center or did not have complete information were excluded from the present study. All the patients were treated in a multi-disciplinary head and neck cancer clinic. Detailed history including clinical presentation, history of risk factors, co-morbidities, and family history was recorded for all patients. A detailed clinical examination was done to determine the anatomical extent of index lesion, presence of other lesions, and status of the neck nodes. A punch biopsy was undertaken in all patients for histopathological confirmation of the diagnosis. All the patients were re-staged as per the AJCC–2010 staging system based on tumor, node, and metastatic extent of lesions during the study. Management protocols, treatment outcomes, follow-up details, and recurrence patterns were collected and analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 16, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Parametric and non-parametric data was displayed as mean (standard deviation) and median (inter-quartile range). Kaplan-Meier analysis was undertaken for survival analysis. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time interval from the date of diagnosis until date of first recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval from the date of diagnosis until death from any cause. The date of diagnosis was deemed as date of registration at our institute as this being a referral hospital for all the cancers. Cox-regression analysis and log-rank test was done to identify the predictive factors for disease recurrence.

Results

There were 740 patients of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma operated in our department between 1995 and 2010. A total of 124 patients with OTSCC qualified for the final analysis in the present study. Tongue constituted the second most common (n = 124, 16.7%) site of oral cancer preceded by combined buccal and gingivo-buccal mucosa cancer (n = 353, 47.7%).

Clinical Presentation

Mean age of the patients was 50.4 ± 12.0 years; it ranged from 25 to 85 years. There was a slight male predominance in the present cohort (men/women = 1.33). The majority (n = 121, 97.5%) of the patients presented with ulcer in the oral cavity; 56 (45.1%) patients also complained of pain. Bleeding and neck swelling were reported by seven (5.6%) patients each. Median duration of symptoms was 4 months (IQR 2–6) and varied from 1 month to 6 years. Physical examination revealed growth along the lateral border in 110 (88.7%), on the ventral surface in 7 (5.6%), and over the tip of tongue in 7 (5.6%) patients. Growth was ulcero-infiltrative in 71 (57.2%), ulcero-proliferative in 50 (40.3%), verrucous in 2 (1.6%), and ulcerated in 1 (0.8%) patient. Mean tumor size (largest dimension) was 3.3 ± 1.4 cm (range 1–9 cm). Neck nodes were palpable in 70 (56.4%) patients—n1 in 48 (38.7%) patients, n2a in 1 (0.8%), n2b in 14 (11.3%), and n2c in 7 (5.6%) patients.

Patterns of Surgical Management

Trans-oral approach was used in 48 (38.7%), while mandibulotomy approach was undertaken in 76 (61.3%) patients. Hemiglossectomy was the most common surgical procedure performed in 71(57.2%) patients followed by anterior partial glossectomy in 32 (25.8%), subtotal glossectomy in 20 (16.1%), and total glossectomy in 1 (0.8%) patient. Primary closure could be achieved in 98 (79.0%) patients, while pectoralis myocutaneous flap was used to augment the residual tongue in 19 (15.3%) patients. Cut surface of tongue was left raw for secondary granulation in four (3.2%) patients. Free radial forearm flap and sternomastoid flap reconstruction were also carried out in two and one patient, respectively.

Ipsilateral neck was addressed surgically in all patients. Depending upon the nodal burden, neck dissection was performed. The majority of the patients (n = 86, 69.3%) underwent modified radical neck dissection (MND)—type I in 76 (61.3%), type II in 7 (5.6%), and type III in 3 (2.4%) patients. Radical neck dissection (RND) was undertaken in 9 (7.3%) patients in view of bulky nodes infiltrating the spinal accessory nerve and/or internal jugular vein. Among 54 clinically N0 patients, supra-omohyoid neck dissection (SOHND) was carried out in 28 (22.6%) patients, rest all had MND in view of intraoperative assessment of significant lymphadenopathy.

Contralateral neck was addressed in 27 (21.7%) patients as seven patients had clinically palpable nodes (n2c), while growth was found to be crossing midline in another 20 patients—SOHND and MND were undertaken in 23 (18.5%) and 4 (3.2%) patients, respectively.

There was no perioperative mortality. Table 1 displays the postoperative complications observed in the patient cohort.

Table 1.

Postoperative complications in the patient cohort (n = 124)

| Early postoperative complication (<30 days) | Delayed postoperative complication (>30 days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Complication | Frequency | Complication | Frequency |

| Wound infection | 4 (3.2%) | Dysarthria | 11 (8.8%) |

| Orocutaneous fistula | 3 (2.4%) | Mini plate extrusion | 3 (2.4%) |

| Neck seroma | 3 (2.4%) | Mini plate infection | 2 (1.6%) |

| Hemorrhage | 2 (1.6%) | Ankyloglossia | 1 (0.8%) |

| Chylous fistula | 1 (0.8%) | Osteomyelitis | 1 (0.8%) |

| Full thickness flap necrosis | 1 (0.8%) | Trismus | 1 (0.8%) |

| Partial flap necrosis | 1 (0.8%) | Orocutaneous fistula | 1 (0.8%) |

| SAN injury | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Septicemia | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Tracheostomy block with tracheostomy | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Urinary retention | 1 (0.8%) | ||

Histopathological Examination

Histopathological evaluation revealed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 122 patients and verrucous carcinoma in 2 patients. The differentiation of the tumor was uniformly reported using Broders system in 122 SCC patients, with well differentiated tumors diagnosed in 92 (75.4%) patients, moderately differentiated in 29 (23.7%) patients, and poorly differentiated tumor in one (0.8%) patient. Median tumor size was 2.5 cm (IQR 1.8–3.5). Negative resection margin was achieved in 121 (97.5%) with a margin positive rate of 2.4%. Ipsilateral neck metastasis was present in 49 (49/124, 39.5%) patients. Contralateral neck metastasis was present in four patients (4/27, 14.8%). Overall, neck metastasis was present in 50 of 124 (40.3%) patients. Among 54 clinically N0 patients, 14 (25.9%) had pathologically confirmed nodal metastasis (occult metastasis). Among 70 patients with clinically palpable neck nodes, 35 of them had pathologically confirmed nodal metastasis. There was no statistically significant association between T-stage and neck node positivity (45.2% in T1, 35.6% in T2, 36.4% in T3, and 50.0% in T4; Fischer exact test p value, 0.67). Table 2 displays the distribution of the patients among various AJCC TNM stages (final staging after histopathological examination).

Table 2.

Final AJCC staging of the patient cohort

| Final stage | Frequency (%) | TNM stage | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 23 (18.5%) | T1N0M0 | 23 (18.5%) |

| Stage II | 38 (30.6%) | T2N0M0 | 38 (30.6%) |

| Stage III | 27 (21.7%) | T1N1M0 | 11 (8.8%) |

| T2N1M0 | 9 (7.2%) | ||

| T3N0M0 | 7 (5.6%) | ||

| Stage IV | 36 (29.0%) | T1N2M0 | 8 (6.4%) |

| T2N2M0 | 12 (9.6%) | ||

| T3N2M0 | 4 (3.2%) | ||

| T4N0M0 | 6 (4.8%) | ||

| T4N2M0 | 6 (4.8%) |

Adjuvant Therapy and Patient Compliance

Adjuvant therapy was advised in 94 (75.8%) patients. Indications of PORT in OTSCC were T2–T4 lesions, high-risk factors (positive/close margins, presence of lymphovascular, or perineural invasion), positive neck nodes, and extra-capsular spread. Concurrent chemo-radiotherapy was added to radiotherapy in the case of positive margins or extra-capsular spread. Among 94 patients who were advised postoperative radiotherapy, 86 patients successfully completed it; six patients defaulted while two patients developed recurrence while awaiting radiotherapy. Over the study period, the dose of postoperative radiotherapy varied from 60 to 64 Gy.

Recurrence Patterns—Local, Regional, and Systemic Relapse

Overall, 25 (20.1%) patients developed disease relapse and 5 (4.0%) patients developed second primaries. Sites of recurrence included local in 11 (8.8%), regional in 13 (10.4%), and systemic in 2 (2.4%); one patient had simultaneous loco-regional recurrence, while another patient had simultaneous systemic and regional relapse. Contralateral regional nodal metastasis was detected in four patients in whom contralateral lymph node dissection was not indicated initially at first surgery.

Disease Outcomes—Disease-Free and Overall Survival

The 27.4% (n = 34) patients were lost to follow-up. For the purpose of the study, patient’s status at the last hospital visit was considered as final in this group of patients. At a mean follow-up of 29.8 months (SD 3.1, minimum = 1, maximum 119.3) for all the patients, 96 (77.4%) were alive and disease free, 7 (5.6%) patients were alive with disease, and 21 (16.9%) patients died of disease. Overall, estimated 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) was 81.5% and 5 year overall survival (OS) was 78.6% (Kaplan-Meier analysis) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing a disease-free survival and b overall survival

Predictive Factors for Recurrence

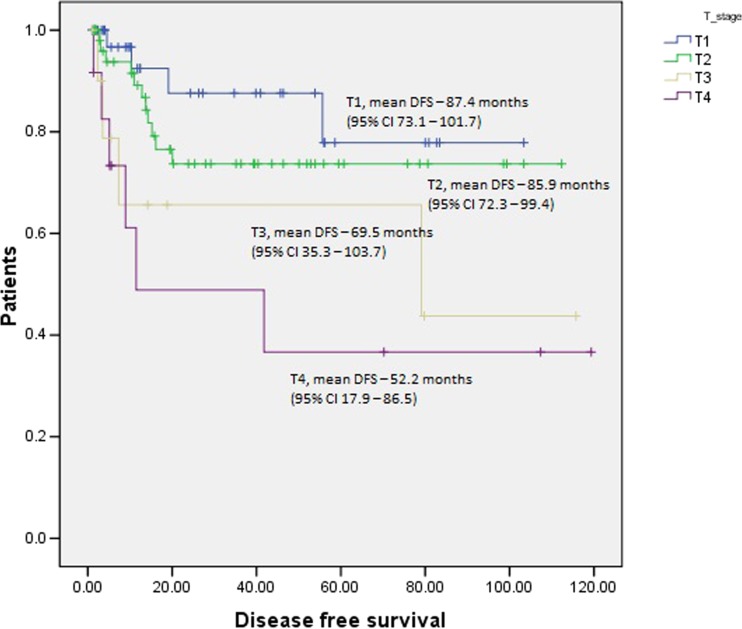

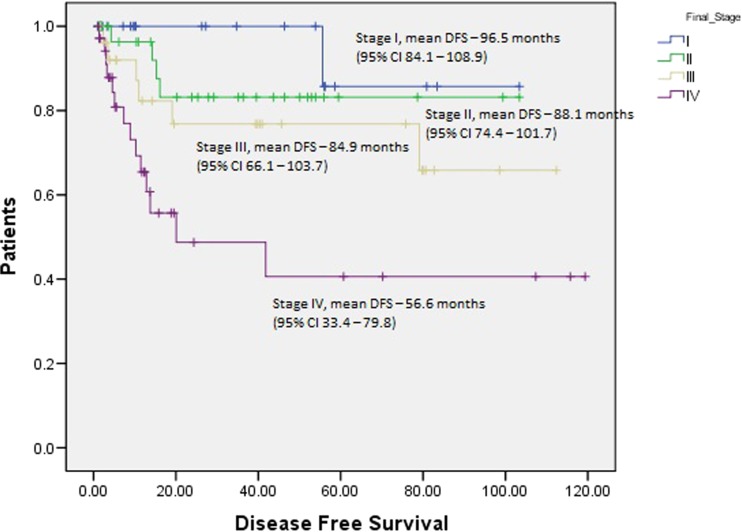

Cox proportional regression analysis predicted tumor size and number of positive nodes to be independent predictive variables for disease recurrence (Table 3). Log rank test revealed significant difference in the mean survival among different T stages (Fig. 2), N stages (Fig. 3), and final TNM stage (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Cox proportional regression analysis to predict the factors associated with recurrence

| Factors | P value | Hazard ratio | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.15 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 |

| Gender | 0.43 | 1.36 | 0.62–2.99 |

| Duration of risk factors | 0.4 | 1 | 0.99–1.00 |

| Ankyloglossia | 0.26 | 1.99 | 0.59–6.71 |

| Tumor size | 0.00 | 1.58 | 1.22–2.04 |

| Differentiation | 0.16 | 1.33 | 0.88–2.00 |

| Margin positivity | 0.7 | 4.53 | 0.00–7.28 |

| Number of positive nodes | 0.00 | 1.5 | 1.25–1.80 |

Fig. 2.

Survival curves for various T stages with respect to disease-free survival (Log rank test). Number of patients in various T stages: T1–42, T2–59, T3–11, T4–12

Fig. 3.

Survival curves for node status (N0 vs. N1 vs. N2) with respect to disease-free survival (Log rank test)

Fig. 4.

Survival curves for final TNM stages with respect to disease-free survival (Log rank test)

Discussion

The present series is one of the few series of Indian patients with OTSCC, who have been treated with uniform management protocols. Moreover, all the data was recorded prospectively. Surgery is the primary modality of the treatment in tongue cancer whenever R‘0’ resection can be achieved with good functional outcome and minimal postoperative morbidity. Radiotherapy has also been advocated by many as a primary modality of treatment in early OTSCC (T1 and T2) as it conserves tongue volume and morphology and thus, purportedly, provides better functional outcome [4, 5]. There are some inherent drawbacks of the radiotherapy as the primary modality of treatment: (a) Complete histopathological information is not available, (b) neck is addressed in all cases by either surgery or external beam radiotherapy irrespective of its requirement, and (c) there are risks of long-term radiotherapy-related complications including osteo-radionecrosis of the mandible and atrophied tongue. Availability of the expertise, radiotherapy facility, and the cost of the treatment are other deterrents for wide spread use of radiotherapy as the primary modality of treatment especially in developing countries where there is perpetual crisis of health resources.

The frequency of neck metastasis in the present series is 40.3% across all T-stages. Previously published literature suggests wide variation in neck positivity ranging from 16 to 83% [6–11]; this difference is likely to be due to inclusion of patients with varied disease stages. Frequency of occult metastasis in the present series was 25.9%; this also varies from 11 to 34% in various previously published studies [7, 8, 10–14]. Frequency of occult metastasis has a bearing in deciding the management of N0 neck. Although a number of factors have been evaluated as predictive factors for node metastasis in clinically N0 neck, tumor thickness has been shown to be the most useful at predicting subclinical neck node metastasis [15, 16]. Byers et al. reported that those with muscle invasion <4 mm, clinically N0, and with a well-differentiated tumor, are likely to have a 14% chance of nodal involvement [17]. Yuen et al. reported that tumor thickness is the most important predictor of neck nodal metastasis—tumor up to 3 mm thickness had 10% nodal metastasis, thickness of more than 3 mm and up to 9 mm had 50% nodal metastasis, and tumor of more than 9 mm had 65% nodal metastasis [18]. These studies suggest that tumor thickness must be considered while deciding for elective neck dissection for clinically N0 neck. Recently published randomized controlled trial concluded that elective neck dissection resulted in higher rates of overall and disease-free survival than did therapeutic neck dissection among patients with early-stage oral squamous-cell cancer; elective node dissection resulted in an improved rate of overall survival (80.0%; 95% CI 74.1 to 85.8), as compared with therapeutic dissection (67.5%; 95% CI 61.0 to 73.9), for a hazard ratio for death of 0.64 in the elective-surgery group (95% CI 0.45 to 0.92; P = 0.01 by the log-rank test) at 3 years [19].

Though established indications for adjuvant radiotherapy in tongue cancer are T3/T4 tumors, positive/close margins, high-risk factors (perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion), N2 or N3 neck nodes, and extra-capsular spread, addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy is warranted in the case of positive margins or extra-capsular spread [20]. The RTOG 9501 study concluded that concurrent postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy significantly improve the rates of local and regional control and disease-free survival among high-risk patients with resected head and neck cancer [21]. Recently published long-term results of RTOG-9501 concluded that those patients who had either microscopically involved resection margins and/or extra-capsular spread of disease showed improved local-regional control and disease-free survival with concurrent administration of chemotherapy at a median follow-up of 9.4 years [22]. The EORTC-22931 study (23) concluded that postoperative concurrent administration of high-dose cisplatin with radiotherapy is more efficacious than radiotherapy alone in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer and does not cause an undue number of late complications. A pooled analysis of patients enrolled in these two trials [21, 23] also concluded that microscopically involved resection margins and extra-capsular spread of tumor from neck nodes are the most significant prognostic factors for poor outcome; the addition of concomitant cisplatin to postoperative radiotherapy improves outcome in patients with one or both of these risk factors who are medically fit to receive chemotherapy [24]. Our institutional policy of adjuvant treatment in tongue cancer has been the same with a few differences; we also recommend adjuvant radiotherapy in T2 tongue tumors and N1 neck nodes in view of aggressive nature of tongue cancer. Adjuvant radiotherapy for isolated neck lymph node involvement in the absence of other risk factors has been a matter of controversy. In a retrospective study of 59 patients of early OTSCC, Chen et al. concluded that adjuvant radiotherapy in pathologic N1 disease significantly improved disease-free survival; the 5-year DFS rates were 81.2 and 53% for the patients with and without PORT, respectively (p = .03) [9].

Loco-regional relapse is the common reason for treatment failure. The relapse rate in the present series was 20.1%: Loco-regional relapse was seen in 17.7% patients. This is much favorable as compared to what has been reported in various other studies (Table 4); the reported local recurrence varies from 4 to 25%, while regional recurrence varies from 6 to 30% [6–14, 25–27]. The 5-year DFS was 81.5% in the present study which is also well comparable to reported DFS of 50–90% among various case series published in literature [6–9, 12–14, 25–27]. The low loco-regional relapse in the present study may be attributed to quality-controlled surgery (margin positivity rate of only 2.8%) and liberal use of radiotherapy (T2 onwards tumor size and any neck node positivity). The reported 5-year overall survival of tongue cancer among previously published studies varies from 56 to 95%. This wide variation in OS is likely to be the result of patient cohorts of different clinico-pathological profiles and management protocols in different studies. Our study also highlights the lower rates of distant failures in our cohort of patients.

Table 4.

Treatment outcomes of oral tongue cancers in various previously published (2005–2015) case series

| Reference | Year | Number of patients | Patient profile | Treatment | Neck dissection | Follow-up | OS | DFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. [9] | 1980–2002 | 59 | pT1-2N1 OTSCC | Surgery ± adj. RT | 100% | Mean = 46 months (range, 12–121) | 5 years OS 74% | 5 years OS 66.6% |

| Mantsopoulos et al. [11] | 1980–2005 | 263 | cT1-2N0-1 | Surgery ± adj. RT or adj. CRT | 82.9% | Mean = 73.3 months (range, 24–300) | 5 years OS = 56.9% | NA |

| Rodrigues et al. [25] | 1980–2007 | 202 | All operated cases of OTSCC | Surgery ± adj. RT | NA | NA | Median OS, 59 months (range 1–262); 5 years OS, 76.8% | 5 years DFS, 71.8% |

| Suslu et al. [7] | 1980–2010 | 138 | All operated cases of OTSCC | Surgery ± adj. RT or adj. CRT | 99.3% | Median = 23 months (6–242) | 5 years OS 81% | 5 years DFS 71% |

| Ganly et al. [12] | 1985–2005 | 216 | cT1-2N0 | Surgery ± adj. RT | 50.9% | Median = 80 months (1–186) | 5 years OS 79% | 5 years DFS 70% |

| Lim et al. [10] | 1992–2004 | 32 | cT2N0 | Surgery ± adj. RT | Mean = 36 months (range, 7–110) | 5 years DSS 68% | ||

| Huang et al. [26] | 1995–2002 | 380 | cT1-2N0 | Surgery ± adj. RT or adj. CRT | 85.3% | Median = 37.months | NA | 5-year 75.7% |

| Fan et al. [8] | 1995–2002 | 201 | All operated cases who received adj. RT | Surgery + adj. RT or CRT | NA | NA | 3 years OS 48% | 3 years DFS 0.8% |

| Akhtar et al. [13] | 1995–2006 | 94 | cT1-2N0 | Surgery + adj. RT | 100% | Average 4 years (range 6 months to 10 years) | OS = 95.7% | DFS = 89.4% |

| Zhang et al. [14] | 1999–2007 | 65 | cT1N0M0 | Surgery ± adj. RT or adj. CRT | 56.9% | Average 56.8 months years (range 4–148) | 5 years OS 85% | 5 years DFS 67% |

| Shim et al. [27] | 2000–2006 | 86 | cT1-2N0-1 | Surgery ± adj. RT | 74.42% | Median = 45 months (4–99) | 5 years 80.8% | 5-year 80.2% |

| Thiagarajan et al. [6] | 2007–2010 | 586 | All operated cases | Surgery ± adj. RT or adj. CRT | NA | NA | Median OS 18 months | Median DFS 17 months |

OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, RT radiotherapy, CT chemotherapy, NA not available

Various studies have identified different factors which are predictive of recurrence. MSKCC study, which included 216 patients with early stage (cT1-2N0) SCC of the oral tongue, reported that occult neck metastases were the main independent predictor of OS, DSS, and DFS on multivariate analysis; patients who had occult metastases had a fivefold increased risk of dying of disease compared with patients who did not have occult metastases (5 years DSS, 85.5 vs 48.5%). A positive surgical margin was the main independent predictor for local DFS (91 vs 66% for a negative surgical margin; p value 0.0004), and depth of invasion was the main predictor for neck RFS (91 vs 73% for depth of invasion <2 and >2 mm, respectively; p value 0.02) [12]. Previously published studies reported 1.1 to 36.5% positive/close margins across various centers. Though there have been reports of using intra-operative ultrasound to assess the margins [28, 29], margin positivity was only 2.4% using hand-palpation method in the present series. Though our center is a training center, we believe that our strict quality-controlled surgery resulted in this low margin positivity. This is almost universally accepted that clear margins (>5 mm) reduce the local failure rates.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged, particularly the loss of patients to follow-up. Almost one fourth of the patients were lost to follow-up in the present study. Another limitation is non-standardization of histopathological evaluation of the specimens in the initial part of the study. Hence, the pathological prognostic factors including depth of invasion, perineural invasion, and lymphovascular invasion could not be assessed in the present study. Levels of lymph nodal involvement were also not uniformly reported. This information could have helped us analyze the requirement of various levels (extent) of lymph node dissection. Despite these limitations, the present study provides useful data related to various clinical, management related, and pathological aspects of tongue cancer in Indian patients.

We conclude that multimodality management including quality-controlled surgery provides safe and effective treatment of oral tongue squamous cell cancer with good OS and DFS with minimal postoperative complications.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C et al GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC cancer base No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2013 [cited 2015 Jun 25]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr

- 2.Krishnamurthy A, Ramshankar V. Early stage oral tongue cancer among non-tobacco users--an increasing trend observed in a south Indian patient population presenting at a single centre. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:5061–5065. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.9.5061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deo S. Computerized clinical database development in oncology. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:S2–S3. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.76229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kobayashi Y, Karasawa K, Komiya Y, Hanyu N, Okamoto M, Chang T-C, et al. Therapeutic results for 100 patients with cancer of the mobile tongue treated with low dose rate interstitial irradiation. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1689–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhalavat R, Mahantshetty U, Tole S, Jamema S. Treatment outcome with low-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy in early-stage oral tongue cancers. J Cancer Res Ther. 2009;5:192. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.57125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiagarajan S, Nair S, Nair D, Chaturvedi P, Kane SV, Agarwal JP, et al. Predictors of prognosis for squamous cell carcinoma of oral tongue. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:639–644. doi: 10.1002/jso.23583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Süslü N, Hoşal AŞ, Aslan T, Sözeri B, Dolgun A. Carcinoma of the oral tongue: a case series analysis of prognostic factors and surgical outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan K-H, Lin C-Y, Kang C-J, Huang S-F, Wang H-M, Chen EY-C, et al. Combined-modality treatment for advanced oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T-C, Wang C-T, Ko J-Y, Lou P-J, Yang T-L, Ting L-L, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for primary early oral tongue cancer with pathologic N1 neck. Head Neck. 2010;32:555–561. doi: 10.1002/hed.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim YC, Choi EC. Unilateral, clinically T2N0, squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue: surgical outcome analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:610–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantsopoulos K, Psychogios G, Künzel J, Waldfahrer F, Zenk J, Iro H (2014) Primary surgical therapy for locally limited oral tongue cancer. BioMed Res Int 738716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ganly I, Patel S, Shah J. Early stage squamous cell cancer of the oral tongue--clinicopathologic features affecting outcome. Cancer. 2012;118:101–111. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhtar S, Ikram M, Ghaffar S. Neck involvement in early carcinoma of tongue. Is elective neck dissection warranted? J Pak Med Assoc. 2007;57:305–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang T, Lubek JE, Salama A, Dyalram D, Liu X, Ord RA. Treatment of cT1N0M0 tongue cancer: outcome and prognostic parameters. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;72:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokemueller H, Rana M, Rublack J, Eckardt A, Tavassol F, Schumann P, et al. The Hannover experience: surgical treatment of tongue cancer--a clinical retrospective evaluation over a 30 years period. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiga K, Ogawa T, Sagai S, Kato K, Kobayashi T. Management of the patients with early stage oral tongue cancers. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007;212:389–396. doi: 10.1620/tjem.212.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byers RM, El-Naggar AK, Lee YY, Rao B, Fornage B, Terry NH, et al. Can we detect or predict the presence of occult nodal metastases in patients with squamous carcinoma of the oral tongue? Head Neck. 1998;20:138–144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199803)20:2<138::AID-HED7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuen AP, Lam KY, Wei WI, Lam KY, Ho CM, Chow TL, et al. A comparison of the prognostic significance of tumor diameter, length, width, thickness, area, volume, and clinicopathological features of oral tongue carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2000;180:139–143. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(00)00433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Cruz AK, Vaish R, Kapre N, Dandekar M, Gupta S, Hawaldar R, et al. Elective versus therapeutic neck dissection in node-negative oral cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:521–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines®). Head and neck cancers, Version 1. 2015. [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jun 27]. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf

- 21.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Campbell BH, Saxman SB, et al. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper JS, Zhang Q, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, Jacobs J, Saxman SB, et al. Long-term follow-up of the RTOG 9501/intergroup phase III trial: postoperative concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma of the Head & Neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, Matuszewska K, Lefèbvre J-L, Greiner RH, et al. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernier J, Cooper JS, Pajak TF, van Glabbeke M, Bourhis J, Forastiere A, et al. Defining risk levels in locally advanced head and neck cancers: a comparative analysis of concurrent postoperative radiation plus chemotherapy trials of the EORTC (#22931) and RTOG (# 9501) Head Neck. 2005;27:843–850. doi: 10.1002/hed.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigues PC, Miguel MCC, Bagordakis E, Fonseca FP, de Aquino SN, Santos-Silva AR, et al. Clinicopathological prognostic factors of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study of 202 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang S-F, Kang C-J, Lin C-Y, Fan K-H, Yen T-C, Wang H-M, et al. Neck treatment of patients with early stage oral tongue cancer: comparison between observation, supraomohyoid dissection, and extended dissection. Cancer. 2008;112:1066–1075. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shim SJ, Cha J, Koom WS, Kim GE, Lee CG, Choi EC, et al. Clinical outcomes for T1-2N0-1 oral tongue cancer patients underwent surgery with and without postoperative radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2010;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baek C-H, Son Y-I, Jeong H-S, Chung MK, Park K-N, Ko Y-H, et al. Intraoral sonography-assisted resection of T1-2 tongue cancer for adequate deep resection. Otolaryngol--Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:805–810. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kodama M, Khanal A, Habu M, Iwanaga K, Yoshioka I, Tanaka T, et al. Ultrasonography for intraoperative determination of tumor thickness and resection margin in tongue carcinomas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:1746–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]