Abstract

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a common spinal deformity with the prevalence of approximately 3%. We previously conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) using a Japanese cohort and identified a novel locus on chromosome 9p22.2. However, a replication study using multi-population cohorts has not been conducted. To confirm the association of 9p22.2 locus with AIS in multi-ethnic populations, we conducted international meta-analysis using eight cohorts. In total, we analyzed 8,756 cases and 27,822 controls. The analysis showed a convincing evidence of association between rs3904778 and AIS. Seven out of eight cohorts had significant P value, and remaining one cohort also had the same trend as the seven. The combined P was 3.28 × 10−18 (odds ratio = 1.19, 95% confidence interval = 1.14–1.24). In silico analyses suggested that BNC2 is the AIS susceptibility gene in this locus.

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a complex, three-dimensional spinal deformity. AIS occurs in otherwise healthy children from the age of 10 to the end of growth1. AIS is a common disease, affecting 2–3% of children, predominantly girls1. Its pathogenesis has been unknown; however twin studies and heritability, in which estimated penetrance in at-risk males is approximately 9% and estimated penetrance in at-risk females is approximately 29%, suggest that genetic components play an important role in the onset of AIS2,3. In fact, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified eight loci associated with AIS4–9.

Confirming the association of previously identified loci in other populations is quite important to identify susceptibility genes. For AIS loci, however, sufficient multi-population studies have not been conducted except for the LBX1 locus on chromosome 10q24.3110–12. We previously identified that an AIS locus on chromosome 9p22.2 represented by rs3904778 and reported BNC2 as a candidate susceptibility gene in the locus based on in vitro and in vivo functional analyses for its causality6. To confirm the association of the 9p22.2 locus and examine its significance in different ethnic populations, we recruited multi-ethnic populations, including Japanese, Han Chinese and Caucasian and conducted a meta-analysis of rs3904778. The results showed that the BNC2 locus is related to risk of AIS globally.

Results

Association of rs3904778 and AIS susceptibility

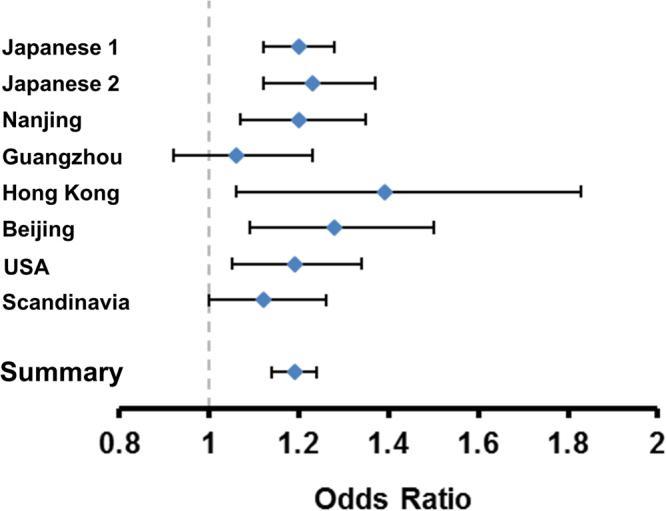

We conducted the meta-analysis of rs3904778 using eight cohorts (Table 1). The data used for the analysis are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. They conformed to the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium (P > 1 × 10−6) and call rate of >99% as previously described quality control criteria9. We evaluated the association in each cohort using the Cochrane-Armitage trend test and and logistic regression. We combined the data using the inverse-variance method assuming a fixed-effects model. Three cohorts were previously reported4,6, and the other five were recruited for this study that included cohorts from Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Beijing, USA, and Scandinavia. For the GWAS cohorts, the possibility of population stratification has been evaluated and is unlikely (λs are all < 1.1)4,6,9. In total, 8,756 cases and 27,822 controls were included in the analysis, which showed a significant association: combined P = 3.28 × 10−18; odds ratio (OR) = 1.19; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.14–1.24 (Table 1). ORs were >1 in all eight cohorts, with little difference between ethnic groups according to the Forrest plot (Fig. 1). The analysis did not show any significant heterogeneity (Table 1), suggesting no statistical difference between studies.

Table 1.

Association of rs3904778 with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

| Population | Study | Number of samples | RAF | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Phet | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||

| Japanese | Japanese 1 | 2,109 | 11,140 | 0.459 | 0.413 | 2.10 × 10−7 | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | |

| Japanese 2 | 955 | 3,551 | 0.476 | 0.424 | 4.46 × 10−5 | 1.23 (1.12–1.37) | ||

| Japanese combined | 3,064 | 14,691 | 5.08 × 10−11 | 1.21 (1.15–1.28) | 0.68 | |||

| Chinese | Nanjing | 1,268 | 1,173 | 0.429 | 0.384 | 1.14 × 10−3 | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | |

| Guangzhou | 659 | 1,063 | 0.354 | 0.340 | 3.77 × 10−1 | 1.06 (0.92–1.23) | ||

| Hong Kong | 193 | 294 | 0.380 | 0.306 | 1.90 × 10−2 | 1.39 (1.06–1.83) | ||

| Beijing | 480 | 861 | 0.457 | 0.397 | 2.50 × 10−3 | 1.28 (1.09–1.50) | ||

| Chinese combined | 2,600 | 3,391 | 6.07 × 10−6 | 1.19 (1.10–1.28) | 0.20 | |||

| East Asian combined | 5,664 | 18,082 | 5.16 × 10−16 | 1.20 (1.15–1.26) | 0.42 | |||

| Caucasian | USA | 1,360 | 7,952 | 0.806 | 0.780 | 5.71 × 10−3 | 1.19 (1.05–1.34) | |

| Scandinavia | 1,732 | 1,788 | 0.801 | 0.782 | 5.44 × 10−2 | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | ||

| Caucasian combined | 3,092 | 9,740 | 1.00 × 10−3 | 1.15 (1.06–1.25) | 0.49 | |||

| All combined | 8,756 | 27,822 | 3.28 × 10−18 | 1.19 (1.14–1.24) | 0.51 | |||

RAF: risk allele frequency, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Forest plots for the association of rs3904778 with AIS susceptibility. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated based on the fixed-effect model. The contributing effect from each study is shown by a square with its confidence interval indicated by a horizontal line. Summary: the combined meta-analysis estimate.

Sex-stratified association

AIS has an ample clinical evidence of sexual dimorphism13. In our previous study, we investigated BNC2 expression in a variety of human tissues and found that BNC2 expression is highest in uterus, suggesting its sex-related biological function6. Therefore, we performed sex-stratified analyses to determine whether a genetic difference existed between male and female. We could obtain sex information for both cases and controls in five cohorts. We could obtain 6,266 cases and 15,292 controls in the female-only analysis, and 485 cases and 10,490 controls in the male-only analysis (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). In both sexes, we could not find genome-wide level significant association (P = 5 × 10−8); particularly in male, the P value did not even reach to the nominal association level (P = 5 × 10−2) (Tables 2 and 3). However, the ORs were similar between male and female, which were similar to that in the analysis disregarding the sex (Table 1).

Table 2.

Association of rs3904778 with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in female.

| Population | Study | Number of samples | RAF | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Phet | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||

| Japanese | Japanese 1 | 2,004 | 4,757 | 0.460 | 0.426 | 3.75 × 10−5 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | |

| Japanese 2 | 905 | 3,135 | 0.476 | 0.417 | 6.30 × 10−6 | 1.27 (1.15–1.41) | ||

| Chinese | Guangzhou | 561 | 594 | 0.352 | 0.356 | 8.40 × 10−1 | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) | |

| Hong Kong | 152 | 192 | 0.378 | 0.315 | 8.30 × 10−2 | 1.32 (0.96–1.81) | ||

| East Asian combined | 3,622 | 8,678 | 4.78 × 10−5 | 1.20 (1.10–1.30) | 0.08 | |||

| Caucasian | USA | 1,159 | 4,826 | 0.807 | 0.780 | 5.50 × 10−3 | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | |

| Scandinavia | 1,485 | 1,788 | 0.800 | 0.782 | 7.31 × 10−2 | 1.12 (0.99–1.26) | ||

| Caucasian combined | 2,644 | 6,614 | 1.50 × 10−4 | 1.16 (1.06–1.26) | ||||

| All combined | 6,266 | 15,292 | 2.93 × 10−7 | 1.18 (1.11–1.25) | 0.16 | |||

RAF: risk allele frequency, CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

Association of rs3904778 with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in male.

| Population | Study | Number of samples | RAF | P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Phet | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | |||||

| Japanese | Japanese 1 | 105 | 6,383 | 0.447 | 0.405 | 2.42 × 10−1 | 1.18 (0.89–1.19) | |

| Japanese 2 | 50 | 412 | 0.480 | 0.482 | 9.73 × 10−1 | 0.99 (0.66–1.50) | ||

| Chinese | Guangzhou | 98 | 469 | 0.367 | 0.319 | 1.87 × 10−1 | 1.24 (0.90–1.71) | |

| Hong Kong | 31 | 102 | 0.387 | 0.289 | 1.45 × 10−1 | 1.55 (0.86–2.81) | ||

| East Asian combined | 284 | 7,366 | 5.62 × 10−2 | 1.19 (1.00–1.43) | 0.67 | |||

| Caucasian | USA | 201 | 3,124 | 0.798 | 0.780 | 5.96 × 10−1 | 1.08 (0.81–1.45) | |

| All combined | 485 | 10,490 | 5.72 × 10−2 | 1.16 (1.00–1.35) | 0.76 | |||

RAF: risk allele frequency, CI: confidence interval.

Fine mapping

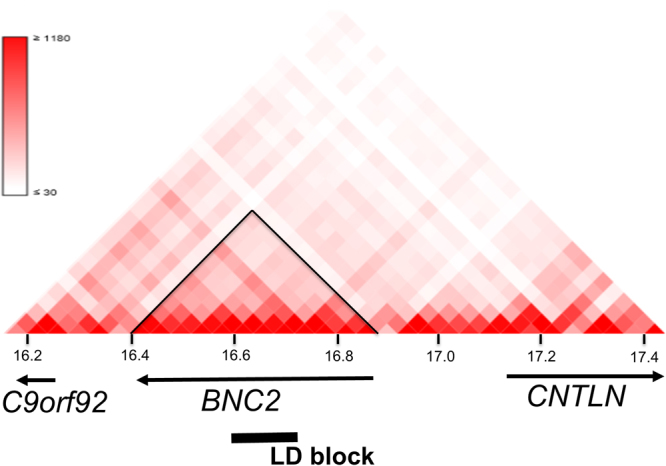

The landmark SNP rs3904778 is located in intron 3 of BNC2, and BNC2 is the only gene contained within the linkage disequilibrium (LD) block (r2 > 0.8) represented by rs3904778. The topologically associated domain (TAD) is the partition of the genome that represents a regulatory unit within which enhancers and promoters can interact14. To identify the candidate susceptibility gene in the locus, we evaluated the TAD around the associated SNPs using H1-mesenchymal stem cell. Hi-C data15 (http://promoter.bx.psu.edu/hi-c/view.php) revealed that BNC2 was the only gene included in the TAD that contained the LD block of the associated SNPs (Fig. 2). The data strongly suggested that BNC2 is the most plausible AIS susceptibility gene at this locus.

Figure 2.

Topologically associated domain around the AIS associated region on chromosome 9p22.2. The Hi-C interaction in H1-mesenchymal stem cell generated by using Interactive Hi-C Data Browser. Only BNC2 lies within the topologically associated domain (black triangle) that contains the linkage disequilibrium (LD) block of the AIS associated SNPs (bold line). The LD block is contained in BNC2.

Discussion

In the present study, we have performed a meta-analysis for the genetic association of rs3904778 with AIS using more than 36,000 subjects from eight independent multi-ethnic cohorts. To date, no large-scale replication study for the association of the AIS locus has been conducted. Previously, we demonstrated that rs3904778 had significant association with AIS in Japanese and Chinese6; however, no evidence has been reported regarding its association in non-East Asian populations. The present study not only gave solid evidence of association of the locus in additional Chinese cohorts, but also revealed that it had significant association in Caucasian, suggesting the global significance of this AIS locus. Previous lack of association in Caucasian may be due to lack of power because the OR of this locus is about 1.2, suggesting relatively large sample size is optimal for identification.

The most significantly associated SNPs are clustered in intron 3 of BNC2. BNC2 is the only gene contained in the LD block of the associated SNPs. TAD containing the LD block only contained BNC2 (Fig. 2). These genome data strongly suggest that BNC2 is the AIS susceptibility gene in the locus. rs10738445 in the locus is in high LD (r2 = 0.9) with rs3904778. Genevar (Gene Expression Variation) data revealed that the risk allele of the functional SNP in this locus, rs10738445, increased BNC2 expression (p = 0.048)6. Our previous in vitro analyses revealed that the risk allele of rs10738445 functioned as an enhancer element and caused increased BNC2 expression through the increased binding of a transcription factor, YY1 (Ying-Yang 1)6. BNC2 was highly expressed in musculoskeletal tissues such as spinal cord, bone and cartilage6. GTEx database also showed similar expression pattern; BNC2 expression was the highest in uterus followed by ovary and nerve. We hypothesized that increased BNC2 expression in these tissues lead to susceptibility of AIS. Actually, the over-expression of Bnc2 in zebrafish caused scoliosis-like deformity6.

To gain insight into the sex difference in AIS susceptibility, we examined sex-stratified association of rs3904778. While the association was almost genome-wide significant level in the female-only analysis (6,266 cases and 15,292 controls), no significant association was obtained in the male-only analysis (485 cases and 10,490 controls) (Tables 2, 3). This is most probably due to be lack of power in the male analysis; in the analysis, sample size was small, especially in the case group, which reflected the female prevalence in all ethnic populations6,7,16. It is of note that the ORs were similar in both sex-stratified analysis. Further analysis with a sufficient sample size will be necessary for the male AIS study, which would inevitably be an international, mutli-center study.

Methods

Subjects and genotyping

We obtained informed consent from all subjects and/or their parents. The ethics committee of RIKEN approved this study. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. AIS subjects were diagnosed through clinical and radiological examinations according to the previously described criteria4,6,9. The subjects in the Japanese and Nanjing-Chinese cohorts were recruited and genotyped as previously described4,6,9. The detail of beadchip information, quality control and statistical analysis were also previously described4,6,9. The details of additional studies (Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Beijing, USA, and Scandinavia studies) were described as below.

Guangzhou study

We recruited AIS subjects from the First Affiliated Hospital and Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University as previously described12. We recruited control subjects from individuals who received scoliosis screening at middle and primary schools in Guangzhou and fracture patients selected from the First Affiliated Hospital and Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. Orthopedic surgeons evaluated these subjects with Adam’s forward bending test and scoliometers to screen scoliosis. We extracted genomic DNA from blood using DNA Blood Mini-kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). The primer extension sequencing (SNaPshot) assay (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) was used for genotyping and the results were analyzed by GeneMarker software (SoftGenetics LLC, PA, USA) at Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China) and checked by visual inspection of I.K. and H.D.

Hong Kong study

We recruited AIS subjects from the Duchess of Kent Children’s Hospital in Hong Kong with previously described inclusion criteria11. We randomly selected control subjects from the subjects recruited for the Genetic Study of Degenerative Disc Disease project17. We confirmed control subjects did not have scoliosis by MRI examination of the spine. We extracted genomic DNA from peripheral blood lymphocytes using standard procedures. We used the PCR-based invader assay (Third Wave Technologies, WI, USA) for genotyping.

Beijing Study

We recruited AIS subjects from Peking Union Medical College Hospital. All subjects underwent clinical and radiologic examination and expert spinal surgeons evaluated scoliosis. We extracted genomic DNA from peripheral blood using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). We used the MassARRAY system (Agena Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) for genotyping.

USA study

We recruited AIS subjects at Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children as previously described7 and used the Illumina HumanCoreExome Beadchip array for genotyping. For controls, we utilized a single dataset of individuals downloaded from the dbGaP web site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db = gap) from Geisinger Health System-MyCode, eMERGE III Exome Chip Study under phs000957.v1.p1 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id = phs000957.v1.p1). The dbGaP controls were previously genotyped on the same microarray platform used for cases. Only subjects of self-reported Non-Hispanic White were included in the present study. Phenotypes of all controls were reviewed to exclude subjects having musculoskeletal or neurological disorders. We applied initial per sample quality control measures and excluded sex inconsistencies and any with missing genotype rate per person more than 0.03. Remaining samples were merged using the default mode in PLINK.1.9 (ref.15). Duplicated or related individuals were removed as previously described18. We used principal component analysis (PCA)19 on the merged data projected onto HapMap3 samples to correct possible stratification20. After quality controls, 9,312 subjects (1,360 AIS patients and 7,952 controls) were included for the current study. We applied initial per-SNPs quality control measures using PLINK including genotyping call-rate per marker (>95%), minor allele frequency (>0.01) and deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (cutoff p-value = 10−4). We imputed genotypes for the region around rs3904778 using minimac321 with the 1000G-Phase3.V.5 reference panel accoding to the instructions of the software (http://genome.sph.umich.edu/wiki/Minimac3_Imputation_Cookbook).

Scandinavia study

We recruited AIS subjects from six hospitals in Sweden and one in Denmark as with previously described inclusion criteria22–25. We recruited control subjects from the Osteoporosis Prospective Risk Assessment cohort and PEAK-25 cohort26,27. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan was performed in both cohorts and subjects with any sign of scoliosis on DXA were excluded. We extracted genomic DNA from blood or saliva using the QIAamp 96 DNA Blood Kit and Autopure LS system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). We used iPLEX Gold chemistry and MassARRAY system (Agena Bioscience, CA, USA) for genotyping. Two persons checked genotype calls using the MassARRAY Typer v4.0 Software (Agena Bioscience).

Statistical analysis

The association between rs3904778 and AIS in each study was evaluated by the Cochrane-Armitage trend test aside from the Japanese 1 and USA studies since rs3904778 was an imputated SNP in the two studies. The Japanese 1 study was analyzed as previously described6. For the USA study, Mach2dat software28 was used to test the imputed allele dosages of rs3904778 by logistic regression with gender and principal components as covariates. Data from the eight studies were combined using the inverse-variance method assuming a fixed-effects model in the METAL software package (http://csg.sph.umich.edu//abecasis/Metal/)29. The heterogeneity among studies was tested using Cochran’s Q test based upon inverse variance weights using METAL.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the individuals who participated in this study. We thank Ms. Yoshie Takahashi, Tomomi Oguma and the members of Laboratory for Genotyping Development for technical assistance. We thank Drs. Nobumasa Suzuki, Masashi Saito and Michihiro Kamata for patient recruitment. We also thank Drs. Jianguo Zhang, Jianxiong Shen, Shugang Li, Yipeng Wang, Hong Zhao and Yu Zhao from Peking Union Medical College Hospital for patient enrollment and clinical evaluation. This work was supported by grants from Japan Orthopaedics and Traumatology Foundation Research No. 344 (to YO), Hong Kong Health and Medical Research Fund (No. 04152256), the Swedish Research Council (No. K-2013-52 × -22198-01-3) and the Scoliosis Research Society, the NIH (No. P01 HD084387) and the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital Research Fund (to CAW).

Author Contributions

Y.O., I.K., Y.T., A.K., C.A., A.G., P.G., E.E., J.K., H.Z., T.Z., D.H, P.S., G.L., Z.W., G.Q., N.W., Y.H.F., Y.Q.S., L.X. and Y.Q. designed and conceived the experiments. Y.O. and K.T. carried out statistical analyses. Y.O., Y.T., M.M., K.W., JSCRG, C.A., TSRHCCG, A.G., P.G., E.E., J.K., D.H. G.L., Y.H.F., and Y.Q. were involved in patient recruitment and assembling of phenotypic data. S.I., M.M. and K.W. designed and supervised the study. Y.O., S.I., M.M., and K.W. conducted data analysis and interpretation. Y.O., S.I., M.M., K.W., A.K., and C.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript before submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

A comprehensive list of consortium members appears at the end of the paper

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-22552-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kota Watanabe, Email: watakota@gmail.com.

Shiro Ikegawa, Email: sikegawa@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Japan Scoliosis Clinical Research Group (JSCRG):

Noriaki Kawakami, Taichi Tsuji, Koki Uno, Teppei Suzuki, Manabu Ito, Shohei Minami, Toshiaki Kotani, Tsuyoshi Sakuma, Haruhisa Yanagida, Hiroshi Taneichi, Ikuho Yonezawa, Hideki Sudo, Kazuhiro Chiba, Naobumi Hosogane, Kotaro Nishida, Kenichiro Kakutani, Tsutomu Akazawa, Takashi Kaito, Kei Watanabe, Katsumi Harimaya, Yuki Taniguchi, Hideki Shigematsu, Satoru Demura, Takahiro Iida, Katsuki Kono, Eijiro Okada, Nobuyuki Fujita, Mitsuru Yagi, and Masaya Nakamura

Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children Clinical Group (TSRHCCG):

Lori A. Karol, Karl E. Rathjen, Daniel J. Sucato, John G. Birch, Charles E. Johnston, Benjamin S. Richards, Brandon Ramo, Amy L. McIntosh, John A. Herring, Todd A. Milbrandt, Vishwas R. Talwakar, Henry J. Iwinski, Ryan D. Muchow, J. Channing Tassone, X. -C. Liu, Richard Shindell, William Schrader, Craig Eberson, Anthony Lapinsky, Randall Loder, and Joseph Davey

References

- 1.Weinstein SL. Natural history. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:2592–2600. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward K, et al. Polygenic inheritance of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a study of extended families in Utah. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2010;152A:1178–1188. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynne-Davies R. Genetic aspects of idiopathic scoliosis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1973;15:809–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1973.tb04919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kou I, et al. Genetic variants in GPR126 are associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:676–679. doi: 10.1038/ng.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyake A, et al. Identification of a susceptibility locus for severe adolescent idiopathic scoliosis on chromosome 17q24.3. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogura Y, et al. A Functional SNP in BNC2 Is Associated with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma S, et al. A PAX1 enhancer locus is associated with susceptibility to idiopathic scoliosis in females. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6452. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu Z, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Chinese girls. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8355. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi Y, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies common variants near LBX1 associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1237–1240. doi: 10.1038/ng.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Londono, D. et al. A meta-analysis identifies adolescent idiopathic scoliosis association with LBX1 locus in multiple ethnic groups. J. Med. Genet (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Fan YH, et al. SNP rs11190870 near LBX1 is associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in southern Chinese. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;57:244–246. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao W, et al. Association between common variants near LBX1 and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis replicated in the Chinese Han population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raggio CL. Sexual dimorphism in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:555–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon JR, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon JR, et al. Chromatin architecture reorganization during stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2015;518:331–336. doi: 10.1038/nature14222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueno M, et al. A 5-year epidemiological study on the prevalence rate of idiopathic scoliosis in Tokyo: school screening of more than 250,000 children. J. Orthop. Sci. 2011;16:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00776-010-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song YQ, et al. Lumbar disc degeneration is linked to a carbohydrate sulfotransferase 3 variant. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4909–4917. doi: 10.1172/JCI69277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson CA, et al. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:1564–1573. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price AL, Zaitlen NA, Reich D, Patterson N. New approaches to population stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:459–463. doi: 10.1038/nrg2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell BD, et al. Using previously genotyped controls in genome-wide association studies (GWAS): application to the Stroke Genetics Network (SiGN) Front. Genet. 2014;5:95. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das, S. et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 48, 1284–1287, 10.1038/ng.3656 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Grauers A, Danielsson A, Karlsson M, Ohlin A, Gerdhem P. Family history and its association to curve size and treatment in 1,463 patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2013;22:2421–2426. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2860-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen MO, Christensen SB, Thomsen K. Outcome at 10 years after treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:350–354. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000197649.29712.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grauers, A. et al. Prevalence of Back Problems in 1069 Adults With Idiopathic Scoliosis and 158 Adults Without Scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Grauers A, et al. Candidate gene analysis and exome sequencing confirm LBX1 as a susceptibility gene for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2015;15:2239–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerdhem P, Akesson K. Rates of fracture in participants and non-participants in the Osteoporosis Prospective Risk Assessment study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2007;89:1627–1631. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B12.18946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuigan FE, et al. Variation in the BMP2 gene: bone mineral density and ultrasound in young adult and elderly women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2007;81:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, Y., Willer, C., Sanna, S. & Abecasis, G. Genotype imputation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet10, 387–406, 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164242 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.