Abstract

Introduction:

Student-generated questions can be a very helpful tool in medical education. The use of this activity can allow the students to feel more involved in the subjects covered and may improve their knowledge and learning. The aim of this study was to identify the effect of question-writing activity as a stimulus factor on learning in midwifery students and determine their perception about this activity.

Methods:

This quasi-experimental study with two groups of pre- and post-tests was conducted on two groups of midwifery students who had taken the immunology course. Two classes of midwifery students (N=62) participated and were randomly assigned to two different groups. One class was selected as the experimental group (n=32) and the other class was considered as the control group (n=30). The experimental group’s students were asked to write questions covering different topics of the syllabus components taught during 15 weeks from February 2016 to May 2016. They were asked to write, answer and explain their multiple-choice questions (MCQs). The students’ performance in immunology course was compared between the two groups at the end of the semester. After their final exam, we asked them to fill in a questionnaire on their views about this activity. The data were analyzed by independent t- test using SPSS software, version 18.

Results:

The differences between pre- and post-test mean scores of the experimental and control groups were 24.53±5.74 and 20.63±5.58, respectively. The results of independent t-test showed that these differences in the two groups were significant (p=0.009). Nevertheless, most of the students stated that question-writing activity as a learning tool is an unfamiliar exercise and unpopular learning strategy.

Conclusion:

Results showed that question writing by students has been found to promote learning when it is implemented as a part of the teaching curriculum in immunology course; therefore, this activity could be effective in improving the students’ learning.

Keywords: Teaching , Learning , Classroom teaching , Student

Introduction

Recently, modern universities offer a new approach supplementing traditional teaching methods in order to help the students in their learning process. Interactive engagement pedagogies contain several teaching methods that encourage the students to generate questions, actively interact with instructors and take ownership of their learning. One of these approaches named student question generation (SQG) allows engaging students in discovering what they view as relevant and important in the course content they have learned, and in generating question items around this (1-3).

SQG is defined as the process by which students construct questions around the materials taught, or areas of an instructional content they deem educationally important and relevant, for learning and assessment purposes. It is used as a helpful tool for practicing to promote learning and interest in the material subject when it is implemented as part of the teaching curriculum. This approach provides insights into their knowledge, understanding, and puzzlement, and acts as a window into their minds (4,5).

A guiding assumption of the research is that deep thinking and reasoning is fostered through contextualized answering of questions. In their ‘depth dynamic model’, It has been postulated how question generation may help the students initiate a process of hypothesizing, predicting, thought-experimenting, and explaining, thereby leading to a cascade of generative activity and helping them to acquire and construct missing pieces of knowledge or resolve conflicts in their understanding. During this process, learning may occur through the formation and rearrangement of cognitive networks as students progressively create explanations and answers to each question. According to information processing theory, such processes can lead to deeper information processing, improved students’ learning and higher levels of cognitive development. Therefore, student-generated questioning requires the students to identify important subjects after reading a passage and generate questions about the points that the students consider important (1,6).

Indeed, student question generation can be viewed as exercises that involve the students in identifying the problem area of a topic. This strategy helps promote involvement by creating questions over what relevant materials should or should not be in an exam. The teachers who use this approach assign it as homework to give students the opportunity to evaluate the teaching topics, and promote their learning abilities and what they have learnt (6,7).

For many years, multiple choice questions (MCQs) have been a traditional method of assessment of students in medical education. Constructing MCQs requires a strong knowledge of the material being assessed as well as a technical skill of making a good question. Therefore, the knowledge required to effectively design a good quality MCQ is greater than that required to answer one. Asking the students to formulate MCQs based on their learning subjects may lead to a deeper understanding of the study topic than other methods (8).

Student-generated questioning make the students identify the important subjects after reading topics, and then formulate MCQ about the points that they think important. Students need to deeply think about the information and decide to create a question, the question’s correct answer, and distracters when creating a MCQ. Therefore, students may be more engaged in the content of the curriculum; more and deeper study of the content promotes their learning (9,10).

Multiple studies have shown that students’ activity in generating questions is an effective way of improving their achievement and promotion of motivation. Yu (2012) showed that hundreds of studies have reported that SQG aids both learning and personal growth (11). Larsen (2008) reveals that this strategy has direct and indirect effects on learning and long-term knowledge retention in medical students. He concluded that this method was a better way to learn materials than further study of the topics (12). Brink in 2004 indicated that the students who designed exams would have a better performance on the final exam (13).

In contrast, some researchers reported that this method had no effects on the students’ learning status. Bekkink has shown that question generation exerts a positive learning effect only on male students (14). In another study, Bottomley reported that although students were solicitous for creating questions, this method had no effects on their learning status (15).

Due to the inconsistent findings in different studies as to this strategy, it is suggested that the researchers carry out more studies in different areas to clarify its dimensions. According to the above-mentioned points, evaluation of this strategy can provide new information for medical education stakeholders and help them for better planning.

Regarding the authors’ experiences, midwifery students were not interested in immunology class, did not read its subjects during the semester, and did not have an acceptable activity for this course. On the other hand, there were documents on positive effects of question generating activity on the students' learning by actively involving them in the course subjects and their accurate concentration on the subjects taught. According to the mentioned reasons, we inserted question generating activity in their Immunology curriculum to engage the students in their subjects actively and continuously; this resulted in an increase in their learning. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the effect of question-writing activity as a stimulus factor in learning in midwifery students and to know their perception about this activity.

Methods

The quasi-experimental study was conducted on 62 midwifery students at Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran. The study sample included the second-year midwifery students who had taken the immunology course. This course is a compulsory subject in the second year of midwifery studies.

Sixty-two midwifery students from two intact classes taught by the same instructor using the same course materials were invited to participate in the study. One class was randomly selected as the experimental group (n=32) and the other class was selected as the control groups (n=30). The duration of the semester was 15 weeks.

This study was conducted using two pre- and post-tests on two classes of midwifery students. The pre-test was undertaken at the beginning of the course and the post-test was conducted on the last session of the course. The pre-test consisted of 50 MCQs focusing on all the topics of immunology that were taught. Teacher and course content for both groups were the same and pre-test and post-test questions were also similar for both groups.

At the first-class session, the students (experimental group) were directed to generate questions around the study content on a chapter-by-chapter basis. A training session was arranged, so that the basic technical aspects and operational procedures related to question-creation in the adopted system were demonstrated and practiced. Furthermore, a 2-hr. training workshop on the logistics of the study, techniques of generating MCQ, and examples of good and bad MCQs was held.

As a general routine, following the instruction of each instructional principle, the students were given to write four questions on the content covered that they regarded as important and relevant. Therefore, students formulated MCQs covering different aspects of the content of Immunology course (at least four MCQs for each topic). They were to asked to read the items, and then formulate MCQs including the correct answer and multiple distractors. Finally, at the end of the semester, each student had designed 60 MCQs in accordance with fifteen topics of immunology course and delivered them to the teacher. In contrast, the students in the control group were engaged in traditional learning activities in the classroom. The question-creation task was part of the graded class activities. In order to balance the students’ scores, all experimental group students received 10% of their total semester score for MCQ generating activity.

Also, at the beginning of their tutorial class in the first week of semester a paper-based MCQ exam (pre-test) with a mixed level of difficulty associated with each topic of immunology course was provided to the participants to individually complete. The pre-test determined the student’s knowledge of the material before they started the immunology course. The aim of using the pre-test exam was to determine the participants’ knowledge of immunology course in the two groups. Second, MCQ exam (post-test) comprising the same questions as the pre-test was provided to the sample group to complete 15 weeks later at the end of the semester.

The scores of the pre- and post-tests were compared to determine whether the students generated MCQ could lead to the increase in the mean scores of the experimental group in the immunology course and encourage learning and improve the student achievement. In this experiment, any improvement in learning was measured by comparing the results of the pre- and post-test before and after the creation of the MCQs in the assessment task. The same immunology topics were used in order to measure the difference between what were known before and after the creation of MCQs.

In the last class session, the students were asked to complete a self-reported questionnaire that assessed their perceptions of the value of the activity and their use of learning strategies as a learning exercise when engaged in the activity. This researcher-made questionnaire contains 7 items which assess the respondent’s learning goal orientation, comprehension of the learned material, their satisfaction, expectations of success, areas that are difficult to understand, and the level of anxiety in this activity. For each item, the students rated the questions on a five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree [1] to strongly agree [5]. The scores for both “agree” and “strongly agree” categories were combined to give a percentage of agreement (%Agreement).

Both positive and negative questions were included in the scales to counteract possible response-set tendencies. As such, scoring on the statements would need to be adjusted so that negative and positive responses could be summed and analyzed. Lower scores on the learning anxiety scale reflect less learning anxiety associated with the exposed learning experience, while higher scores on the other scale reflect more favorable perceptions toward the value of the activities with regard to enhancing achievement.

To determine the validity of the questionnaire, experts in medical education reviewed the questionnaire (4 faculty members and two students) and after receiving the comments and modifying the questions, the validity of questionnaire was approved. The reliability was assessed using internal consistency and calculating Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.65.

To investigate the relationship between activity question generation and the overall performance, we ranked the students based on their grade point average (GPA). That is, the students with the highest grade were defined as rank 1(higher 50% GPS), and those with the lowest grade (lower 50% GPA) as rank 2. Finally, based on GPAs, the students were divided into two groups: those with GPA more than 50% were considered as “high academic performance” and less than 50% as “low academic performance”.

Regarding moral principles, all the experimental and control students contributed voluntarily to the research. The privacy of the students was granted by the researcher. A special code was assigned to each student to observe the obscurity of the research and they ensured that data would be reported anonymously.

In the beginning, homogeneity between the experimental and control groups was investigated. The homogeneity was used to determine whether the knowledge levels of participants were distributed similarly across the control and experimental groups.

Since the study was conducted using a pretest-posttest with control group, in the beginning, the difference between pre-test and post-test scores was calculated and then compared based on the students’ scores. The scores of the first and final exams (pre- and post-test) were gathered and t-test was used to compare pre- and post-test scores in the two groups.

The perceptions of the helpfulness of the questioning activity for students in the intervention group were analyzed using independent t-test. All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 18 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Results were considered statistically significant for a p-value less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 62 midwifery students (experimental=32, control=30) participated in the present study. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics of the two groups. The mean scores of the pre-tests exam in the experimental and control groups were 13.69±3.58 and 12.77±1.61, respectively (p=0.202). There were no significant differences between students in the experimental and control groups. The results of the t-test are summarized in Table 1. Students in both groups ranked the learning methods similarly with no statistical differences between the groups; this suggests that the two groups were homogenous.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of age, GPA and pre-test scores of the experimental and control groups

| Variable | Control | Experimental | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20.53±0.97 | 20.91±0.99 | 1.490 | 0.141 |

| GPA | 16.15±1.70 | 16.37±0.98 | 0.625 | 0.534 |

| Pre-test | 12.77±1.61 | 13.69±3.58 | 1.289 | 0.202 |

| Post-test | 33.40±5.48 | 38.22±5.48 | 3.46 | 0.001 |

| Differences of pre- & post-test | 20.63±5.58 | 24.53±5.74 | 2.71 | 0.009 |

The pre-test determined the student’s knowledge of the material before they started creating MCQs. The students’ pre-test results revealed that the student’s knowledge of topics was low. This, however, was expected because the students had not been exposed to the topics covered in the pre-test.

Comparison of the mean scores of the post-tests showed a significant difference between the experimental and control groups (38.22±5.48 vs. 33.40±5.48, p= 0.001). This shows that the mean scores of the two groups significantly increased at the end of the semester. In addition, the mean scores of the experimental group were much better than the control group (Table 1). Comparison of the results of t-test in Table 1 revealed that the difference between pre- and post-test mean scores of the experimental and control groups was statistically significant. (20.63±5.58 vs. 24.53±5.74, p= 0.009).

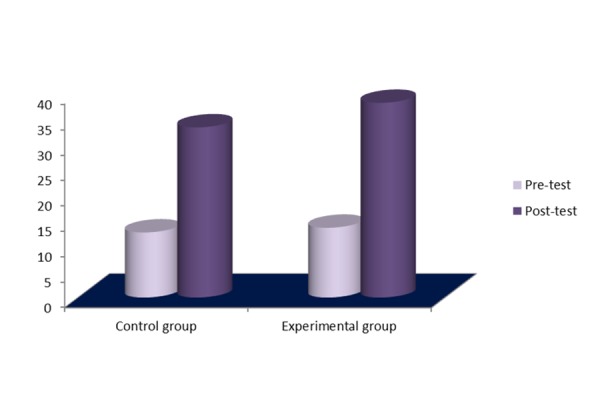

Figure 1 shows the pre- and post-test scores of two groups. Both groups showed improvement in their post-test scores. However, the experimental group did much better than the control group and there was a statistical difference between the two groups.

Figure1.

Pre- and post-test scores of the two groups' students

Students’ Perceptions of the Exercise

To assess how the students perceived the process of student-writing MCQ, we surveyed the students in the intervention group. All thirty-two students in the experimental group responded to the questions (response rate 100%) on the value of creating MCQs as a learning strategy. Percentage and mean scores of the students’ opinions about this activity are shown in Table 2. The global mean score of their opinions regarding this plan was 2.57±0.56 out of 5; this means the students generally had no positive idea regarding the effectiveness of the plan. Results of our research showed that the case group students believed that this plan had no effects on the improvement of studying and learning in them. The majority of the students showed the least interest in writing questions; they reported that it did not assist them in making connections between ideas learned in immunology courses. They stated that they felt uncomfortable and anxious about participation in the program. Overall, the students slightly agreed with creating MCQs. They also mentioned they would not like to take part in similar activity in the future (Table 3).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics on the students' perceptions toward the usefulness of writing MCQ

| After participating this in program and creating MCQs, I have... | 1 ƒ (%) | 2 ƒ (%) | 3 ƒ (%) | 4 ƒ (%) | 5 ƒ (%) | 4+5 ƒ (%) | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Achieved a better understanding of the issues | 9(28%) | 16(50%) | 2(6%) | 3(10%) | 2(6%) | 5(16%) | 2.16 | 7 |

| 2. Developed approaches to study and Learning skills | 5(16%) | 14(44%) | 9(28%) | 3(10%) | 1(3%) | 4(13%) | 2.41 | 6 |

| 3. Studied the topics deeper and more carefully | 3(10%) | 15(47%) | 7(22%) | 5(16%) | 2(6%) | 7(22%) | 2.63 | 5 |

| 4. Felt the anxiety and confusion of participation in the program. | 4(13%) | 6(19%) | 8(25%) | 11(34%) | 3(10%) | 14(44%) | 3.09 | 3 |

| 5. Felt uncomfortable and I did not participate in the future in these programs | 1(3%) | 6(19%) | 6(19%) | 15(47%) | 4(13%) | 19(60%) | 3.47 | 1 |

| 6. Felt the pressure of learning in this program. | 3(10%) | 7(22%) | 8(25%) | 10(31%) | 4(13%) | 14(44%) | 3.16 | 2 |

| 7. The overall agreement with this program (creation MCQ) | 3(10%) | 14(44% | 6(19%) | 7(22%) | 2(6%) | 9(28%) | 2.72 | 4 |

Table 3.

Comparison of the students' perceptions toward writing MCQ by academic performance

| After participating in this program and creating MCQs, I have... | Low GPA | High GPA | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | Mean±SD | |||

| 1. Achieved a better understanding of the issues | 2.56±1.15 | 1.75±1.0 | 2.13 | 0.042 |

| 2. Developed approaches study and Learning skills | 2.75±1.0 | 2.06±0.85 | 2.09 | 0.045 |

| 3. Studied the topics deeper and more carefully | 3.06±1.18 | 2.19±0.75 | 2.50 | 0.018 |

| 4. Felt the anxiety and confusion of participation in the program | 3.0±1.26 | 3.19±1.16 | - 0.436 | 0.67 |

| 5. Felt uncomfortable and I did not participate in the future in these programs | 3.44±1.03 | 3.50±1.09 | -0.166 | 0.87 |

| 6. Felt the pressure of learning in this program | 3.0±1.21 | 3.31±1.19 | -0.735 | 0.47 |

| 7. The overall agreement with this program (creation MCQ) | 2.94±1.29 | 2.50±0.89 | 1.12 | 0.27 |

Descriptive statistics of the students' perceptions toward the usefulness of writing MCQ according to their academic performance are shown in Table 3. Comparing the opinions of students with high and low academic performance showed that students with low academic performance had more positive attitude towards this activity.

Discussion

This quasi-experimental study investigated the impact of writing questions on the final exam scores of immunology course in the midwifery students. Comparison of the scores in the experimental and control groups showed that utilization of question-writing activity led to enhancement of the students’ scores and academic performance. Higher scores of the experiment group students were probably related to more study and exercise of immunology subjects because practice is the acceptable basis of the learning.

There are reports that have shown question-writing as a learning tool in improving the students’ performance. Previous studies on student question-generation demonstrated that it had beneficial effects with regard to promoting the learners’ cognitive, affective and social growth (16-18). Hutchinson et al. performed a similar study on medical students and used a pretest-posttest design; any improvement in learning was measured by comparing the results of the pre- and post-test MCQs exam before and after the creation of the MCQs by students (17). They found that the intervention resulted in effective learning. In another study, Bobby et al. showed that creation of questions was highly effective in understanding the topic for all students (18). Furthermore, Bekkink et al. carried out a prospective study during a bachelor general pathology course including 459 medical students; similar to our study, the students were asked to formulate questions and present them the following day (14). They indicated that question-writing activities during the semester seemed to exert a positive learning effect on male students.

These findings are in line with those of previous studies and educational theory indicating an association between question-writing activities and academic performance of the students. The results of a study pointed out that practicing writing questions before an exam would be beneficial; and the students that used this strategy often had higher grades and better results on the final exams (19). It is believed that using students writing questions method is a way of encouraging students to focus more on learning material in the classroom; also, this strategy enables the students to make connections to things they are interested in as well as keep them interested in what they need to learn (1,9,20).

Since using student-generated questions in the classroom was shown to increase the comprehension of the material, it is recommended that by assigning the tasks to the students and involving them in materials of the course, they ultimately improve their academic performance and promote active learning behavior. We believe that such an approach may be useful when reviewing other areas of research on cognitive strategy instruction, and it is hoped that this activity can be implemented in other universities in future.

Some studies have not reported the positive effect of writing questions on students’ learning (8,10,21). Job et al. and Abraham performed a similar study among medical students but did not measure the effects on the examination scores and academic performance of students (10,21). In order to clarify these results, we can mention that the differences in the findings of various studies might be related to target population, sampling methods, questions type, and duration of the study or course of students. Further studies in this area could help to clarify the dimensions of this issue. Researchers believe that this strategy may not help every student, but it has been shown to help those that put a thoughtful effort into the creation of questions.

In this study, the perceptions of students about the question-writing activities were also surveyed. The results showed that students did not have a positive attitude towards this strategy and they stated that it was not a useful activity for students’ learning. Students stated that they were annoyed of doing these exercises throughout the semester. A possible explanation for unwillingness of the students is heavy paperwork during the semester, as a large number of students have taken part in question writing exercises during their education and perceived the task as difficult. These results are somewhat in line with earlier research evidence on the students’ writing question. In a study, over half of the students did not show motivational behavior for question-writing; and when they were asked why they did not participate, they ultimately answered it had been due to lack of time 2. The findings of some studies revealed that although students did not express disagreement with homework completion, they suffered from the pressure to do homework (22,23).

Students were not satisfied with this activity due to the high amounts of the course subjects, lack of time for question generating, difficulty of this activity. It means that they do not have a positive attitude toward this activity because they were not interested in doing a difficult and time consuming job. Immunology, as a basic course with 2 units in the second semester, is a non-specific and non-core subject for midwifery students and they are not willing to pay more time for that and it is another probable reason for their dissatisfaction. Despite these two points, their interaction in the activity and more subject studying for question generating result in their better learning and more scores. Therefore, although this study did not show a positive attitude towards question generating strategy, it revealed significant positive effect of this activity on the students' learning.

Overall, although this study performed a statistical measurement of learning benefits after the question-writing activities, it showed that this activity did not enhance the students' motivation and positive dispositions. To find the reason why students disagreed with this activity requires more research. If students consider emotional-psychological climate of a class as a competitive environment in which achieving the goals requires effort, then they will find out that this activity is useful and improves learning. Thus, if teachers have characteristics such as interest in teaching and learning, the ability to manage class, positive views towards class discussion, proficiency on the contents, and higher expectations from students, then most probably students are more motivated and try to get involved in this activity and have more tendency toward this strategy.

Furthermore, this study indicates that low performing students had better perceptions toward the questioning activity while the high performing students did not have any positive attitudes. This finding may be interpreted as a desirable effect because the weaker students were supported. This result is consistent with those of the study conducted by Job et al. that evaluated the views of students toward questioning activity (14). They reported that the low performing students had a significantly better attitude while the high performing students did not consider it a useful activity. They speculated that low performing students spent more time doing these exercises, so they had a more positive attitude toward this activity.

Low and high performing students have different learning style preferences; high performing students confirm greater enjoyment in taking responsibility for their own learning and generally have a higher degree of intrinsic motivation (24). This suggests that low performing students need more or other challenges to be motivated to learn.

In fact, implementation of this program creates motivation in the low performing students and has attracted their attention. However, this behavior was not observed in high performing students; this group of students used their own approaches to study and learning and did not much believe in these types of activity.

The limitations of this study that might have affected the results are sample size and gender of the participants. The sample used was rather small in size and all of the students who participated in this study were female. The generalizability of this study to other contexts dealing with subject matters of a different nature should thus be exercised with caution. The course was only 15 weeks long. Thus, we had relatively little time to support the students in developing positive attitudes about interactive engagement and conceptual learning. Using similar course content, homogenous students, the same teacher, and pre- and post-test were the strengths of this study. It is also worth pointing out that the questionnaire used to collect data on the observed variables in this study was a self-reported questionnaire using Likert scale, and the issues surrounding this, including socially desirable and response biases, should be noted.

It is recommended that a study should be conducted on medical students in the future. The challenge will be to make sure that the instructors in these courses are open to using this pedagogy and the teaching methods and learning environments in different sections are comparable.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed that students’ writing questions could lead to better academic achievement and students' learning. Therefore, involvement of students in writing questions is a technique that can be used to improve academic performance in universities. In this activity that required the students to write examination questions was effective not only as a graded group assignment, but also as a tool to encourage classroom engagement and lead to better examination scores. Although in this study the measurement of learning showed gains after writing MCQ in midwifery students in immunology course, students did not enhance motivation and positive dispositions toward this activity.

Finally, this strategy can be successfully implemented in teaching curricula in future for better training of the students. More research is needed in future to better investigate the importance and suitability of the students’ writing questions in medical education.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank all participants. This study was funded by Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences and confirmed by the Ethics Committee of the university: IR.AJUMS.REC.1395.231.

Conflict of Interest:None declared.

References

- 1.Song D. Student-generated Questioning and Quality Questions: A literature review. Research Journal of Educational Studies and Review. 2016;2(5):58–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poot R, De Kleijn RA, Van Rijen HV, Van Tartwijk J. Students generate items for an online formative assessment: Is it motivating? . Med Teach. 2017;39(3):315–20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu FY, Wu CP, Hung CC. Are there any joint effects of online student question generation and cooperative learning? . The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 2014;23(3):367–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu FY, Wu CP. The effects of an online student-constructed test strategy on knowledge construction. Computers & Education. 2016;94:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lam R. Can student-generated test materials support learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation. 2014;43:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu FY, Pan KJ. The Effects of Student Question-Generation with Online Prompts on Learning. Educational Technology & Society. 2014;17(3):267–79. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papinczak T, Babri AS, Peterson R, Kippers V, Wilkinson D. Students generating questions for their own written examinations. Advances in health sciences education. 2011;16(5):703–10. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer E, Devitt P. Constructing multiple choice questions as a method for learning. Annals-academy of medicine Singapore. 2006;35(9):604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milner-Bolotin M, Egersdorfer D, Vinayagam M. Investigating the effect of question-driven pedagogy on the development of physics teacher candidates’ pedagogical content knowledge. Physical Review Physics Education Research. 2016;12(2):020128. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jobs A, Twesten C, Göbel A, Bonnemeier H, Lehnert H, Weitz G. Question-writing as a learning tool for students–outcomes from curricular exams. BMC medical education. 2013;13(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu FY, Wu CP. Student question-generation: The learning processes involved and their relationships with students’ perceived value. Journal of Research in Education Sciences. 2012;57(4):135–62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen DP, Butler AC, Roediger HL. Comparative effects of test‐enhanced learning and self‐explanation on long‐term retention. Med Educ. 2013;47(7):674–82. doi: 10.1111/medu.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brink J, Capps E, Sutko A. Student exam creation as a learning tool. College Student Journal. 2004;38(2):262. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekkink MO, Donders AR, Kooloos JG, De Waal RM, Ruiter DJ. Challenging students to formulate written questions: a randomized controlled trial to assess learning effects. BMC medical education. 2015;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottomley S, Denny P. A participatory learning approach to biochemistry using student authored and evaluated multiple‐choice questions. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2011;39(5):352–61. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shakurnia AM. The Effects of Student-Generated MCQs on their Academic Achievement. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2015;15:521–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutchinson D, Wells J. An inquiry into the effectiveness of student generated MCQs as a method of assessment to improve teaching and learning. Creative Education. 2013;4(07):117. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bobby Z, Koner BC, Sridhar M, Nandeesha H, Renuka P, Setia S, et al. Formulation of questions followed by small group discussion as a revision exercise at the end of a teaching module in biochemistry. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2007;35(1):45–8. doi: 10.1002/bmb.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez-Elez M, Pardines I, Garcia P, Miñana G, Roman S, Sanchez M, et al. Enhancing students’ learning process through self-generated tests. Journal of Science Education and Technology. 2014;23(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tofade T, Elsner J, Haines ST. Best practice strategies for effective use of questions as a teaching tool. American journal of pharmaceutical education. 2013;77(7):155. doi: 10.5688/ajpe777155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham RR. Student generated questions drive learning in the classroom. Med Teach. 2009;32(9):789. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.513224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson GF, McFarland B, Worthington R. Student-Created Assignments in an Undergraduate Accounting Information Systems Course: Student and Faculty Perceptions. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice. 2013;13(1):80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu FY. Scaffolding student-generated questions: Design and development of a customizable online learning system. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25(5):1129–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu FY, Liu YH. Creating a psychologically safe online space for a student‐generated questions learning activity via different identity revelation modes. British Journal of Educational Technology. 2009;40(6):1109–23. [Google Scholar]