Introduction

When defining the balance between tumor control and toxicities, considerable caution must be exercised near organs with serial functional subunits, such as the spinal cord and named nerves, because of the potential for irreversible damage. In such challenging clinical scenarios, the highly targeted nature of intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) may offer a viable option to improve patient outcomes.1, 2 Traditionally, IORT refers to the delivery of focused radiation immediately after surgical resection via intraoperative electron beam, superficial x-ray, or high- or low-dose rate (HDR; LDR) mesh techniques.1 Although these methods provide a theoretical benefit because of their capacity for precise radiation delivery through a single procedure, several disadvantages have limited their use in clinical practice. Both electron and x-ray IORT require the costly installation of an intraoperative linear accelerator. The large size and customization limitations of currently available IORT electron cones make targeting of complex anatomic surfaces difficult. HDR IORT requires the use of an HDR remote after-loader and a shielded operating room.1 When using LDR mesh, source orientation and spacing can be difficult to maintain during mesh customization, leading to large dose inhomogeneities.

The CivaSheet (CivaTech Oncology Inc., Durham, NC), an implantable unidirectional palladium-103 (Pd-103) planar low-dose brachytherapy device, overcomes many of these shortcomings and offers a novel radiation delivery approach in sites with close proximity to organs at risk. The CivaSheet consists of individual Pd-103 sources encapsulated in an organic polymer and embedded within an 8 mm × 8 mm grid that consists of a flexible bio-absorbable substrate. The sources are shielded on one side with gold to attenuate the dose to only one tenth of the total dose.3, 4, 5 The CivaSheet received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2014 for planar LDR brachytherapy. A recent abstract demonstrated that, in a patient with a pelvic side wall malignancy, the device offered significant reductions in dosage to critical structures, such as the bowel and bladder, compared with conventional LDR.4 Here we describe the case of a 78-year-old man with persistent squamous cell carcinoma of the left axilla after external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) who underwent surgical resection and CivaSheet implantation.

Case report

A 78-year-old male patient initially presented with a palpable left axillary mass. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a 6.9 cm × 7.1 cm × 5.1 cm lesion in the axilla that was inseparable from the brachial plexus and axillary vessels. A biopsy indicated HPV+ squamous cell carcinoma. A dose of 58 Gy, prescribed to the 95% isodose line (±5%), was delivered in 2 Gy fractions with 3-dimensional conformal EBRT with concurrent weekly administration of cisplatin 40 mg/m2 at an outside facility. Magnetic resonance imaging scans obtained 3 months post-treatment revealed that the mass had decreased in size to 3.8 cm × 2.5 cm × 3.9 cm but maintained encasement of the axillary artery, axillary vein, and several inferior branches of the brachial plexus (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging scans obtained before treatment (left) and within 3 months of initial external beam radiation therapy (right) revealed a decrease in the size of the mass but indicated persistent encasement of the axillary vessels and several inferior branches of the brachial plexus.

Concerns with regard to increased toxicity to the axillary structures discouraged further EBRT; therefore, we opted for the intraoperative use of the CivaSheet. Given that we were treating microscopic disease within formerly irradiated tissue, a prescription dose of 20 Gy at 5 mm from the surface of the mesh was considered adequate because of its delivery of a biologically effective dose (BED)-10 of 39.8 Gy and equivalent dose (EQD)-2 of 33.2 Gy to the tumor bed while limiting the D2cc for the brachial plexus to a BED3 of 27.9 Gy and EQD2 of 16.7 Gy, based on postimplant analysis. This approach allowed us to significantly limit the dose to the brachial plexus. We selected a composite dose constraint of D2cc of 75 Gy on the basis of recent data showing elevated clinical brachial plexopathy rates beyond this threshold.6 We met this constraint, with an estimated composite EQD2 of 74.7 Gy, which we would be unable to obtain with EBRT to a tumor bed EQD2 of ≥30 Gy. Additional calculations demonstrating the dose delivered to the brachial plexus are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Calculations demonstrating the radiation dose delivered to the brachial plexus

| Volume | BED3 (Gy) | EQD2 (Gy) |

|---|---|---|

| D1cc | 39.8 | 23.8 |

| D2cc | 27.9 | 16.7 |

| D3cc | 24.4 | 14.6 |

BED, biologically effective dose; EQD, equivalent dose.

During the surgical procedure, the mass was dissected from the axillary structures. Intraoperative assessment of the margins along the brachial plexus sheath were negative for carcinoma. The membrane then was cut to size and tightly sewn down to the cavity surrounding the tumor bed (Fig 2). The pectoralis margin and 15 axillary lymph nodes that were assessed subsequently were also negative for carcinoma. We obtained postoperative computed tomography images of the implanted membrane for dosimetric analysis (Fig 3).

Figure 2.

The CivaSheet was cut to size and sewn into the tumor cavity with 3-0 Vicryl sutures.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography images of the implanted device obtained for dosimetric analysis, before (top row) and after (bottom row) implantation, with the brachial plexus contoured (green line).

The patient was discharged on the same day with instructions on wound care and radiation safety. The incision healed well, with no signs of infection, seroma, or lymphadenopathy during the monthly follow-up visits. At his most recent 8-month follow-up visit, the patient was documented to only have minor shoulder pain.

Discussion

Despite studies that suggest improved disease control with aggressive treatment of local axillary tumor recurrences, reirradiation and boost dosing remain controversial due to concerns with regard to toxicity to the surrounding structures.7, 8 The CivaSheet is a new device that may offer an acceptable alternative because its unidirectional nature facilitates highly localized radiation delivery while limiting toxicity to organs at risk. In our patient, orienting the radioactive source toward the brachial plexus allowed for irradiation of any microscopic disease within the tissue immediately overlying the tumor cavity. However, because this radiation was only prescribed to a depth of 5 mm, deep neurovascular contents of the axilla were largely protected (Fig 4). Conversely, because the opposing surface consisted of muscle and fat tissue that was unlikely to harbor residual disease, adhering the nonradioactive side to this surface likely improved postoperative wound healing without compromising disease control. The unidirectional design also permitted for easy identification of orientation during placement.

Figure 4.

Visualization of the radiation dose distribution.

Advantages of the CivaSheet include its bio-absorbability, ease of visualization with imaging, potential for intraoperative customization, ability to complement various treatment approaches including EBRT and surgical resection, and ease of implantation with minimal training. Its malleability is likely to be particularly useful in treating irregularly shaped surgical cavities, such as those created after breast lumpectomies or pelvic side wall resections.

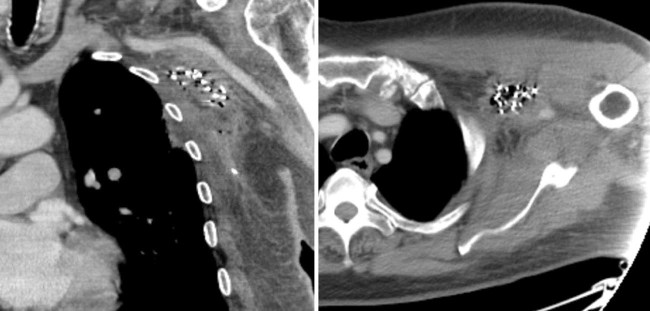

Interestingly, the CivaSheet also overcomes several shortcomings observed even among those LDR mesh devices that use the same isotope. As the vicryl sutures of traditional LDR mesh bend and curve around irregular surfaces during placement, the spacing and orientation of the radioactive seeds may be altered, leading to unpredictable variations in isodose geometry. In contrast, the polymer encapsulation of the Pd-103 Civa seeds before embedding within the membrane allows the sources to maintain their orientation in space and deliver radiation in accordance with the predetermined geometry. Additionally, unlike older LDR mesh devices that run the risk of source dispersion after mesh degradation, the polymer encapsulation allows the seeds to maintain their placement even as the membrane is absorbed over time. In our patient, 3-month postimplantation imaging demonstrated that radioactive source geometry had remained stable since the initial implantation (Fig 5).

Figure 5.

Coronal (left) and axial (right) computed tomography scans obtained 3 months postimplantation indicate the presence of the source seeds within the region of initial placement. Imaging also demonstrates postsurgical changes that are suggestive of fibrosis.

Despite its many advantages, the CivaSheet also has a number of limitations. First, it is an expensive product (~$21,000) and billing codes for reimbursement are currently pending. Logistic hurdles include the coordination of ordering and receiving the product ahead of the procedure, organizing the multiple personnel required, and following standard radiation safety precautions. Fortunately, the relatively simple design of the sheet does not require detailed training, and initial feedback from our surgical oncology team focused on its ease of use, flexibility in implantation, and myriad additional potential applications.

Given the encouraging results from prior publications,3, 4, 5 2 studies were recently initiated to further evaluate the safety, efficacy, and clinical benefits of this device. In September 2016, the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute Fast Track Program approved the CivaSheet for the first phase of an 80-patient pancreatic cancer study with the expectation that it will be well tolerated and have a favorable impact on local recurrence.

Although radiation remains an integral portion of pancreatic cancer treatment, given the proximity of the pancreas to critical organs, toxicity concerns have largely limited aggressive radiation therapy.9 In this phase 1/2 study (NCT02843945), patients will undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation. If they are deemed borderline resectable or have concern for close/positive margins at the time of pancreaticoduodenectomy, patients will be considered for CivaSheet insertion into the surgical bed.

A second pilot study being conducted by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (NCT02902107) aims to evaluate the feasibility of successful implantation and associated side effects in patients undergoing surgery for abdominal and pelvic tumors. Although the device has only been used in a limited number of malignancies to date, with further studies, the CivaSheet may be more widely incorporated into oncological treatment plans. In cases in which local control with the current standard of care is suboptimal and wherein existing techniques for the delivery of radiation therapy are inadequate, the CivaSheet may find its niche in the toolkit of the radiation oncologist.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Harrison L.B., Enker W.E., Anderson L.L. High-dose-rate intraoperative radiation therapy for colorectal cancer. Oncology. 2015;9:737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sedlmayer F., Reitsamer R., Wenz F. Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) as boost in breast cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2017;12:23. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0749-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aima M., Reed J.L., Dewerd L.A., Culberson W.S. Air-kerma strength determination of a new directional 103Pd source. Med Phys. 2015;42:7144–7152. doi: 10.1118/1.4935409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivard M.J. Low-energy brachytherapy sources for pelvic sidewall treatment. Brachytherapy. 2016;15:S22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivard M.J. A directional (103)Pd brachytherapy device: Dosimetric characterization and practical aspects for clinical use. Brachytherapy. 2016;16:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amini A., Yang J., Williamson R. Dose constraints to prevent radiation-induced brachial plexopathy in patients treated for lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:e391–e398. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentzen S.M., Dische S. Morbidity related to axillary irradiation in the treatment of breast cancer. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2000;39:337–347. doi: 10.1080/028418600750013113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merino T., Tran W.T., Czarnota G.J. Re-irradiation for locally recurrent refractory breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:35051–35062. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds R.B., Folloder J. Clinical management of pancreatic cancer. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2014;5:356–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]