Abstract

Purpose

To examine the relationship of caste and class with perceived discrimination among pregnant women from rural western India.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was administered to 170 pregnant women in rural Gujarat, India, who were enrolled in a longitudinal cohort study. The Everyday Discrimination Scale and the Experiences of Discrimination questionnaires were used to assess perceived discrimination and response to discrimination. Based on self-report caste, women were classified into three categories with increasing historical disadvantage: General, Other Backward Castes (OBC), and Scheduled Caste or Tribes (SC/ST). Socioeconomic class was determined using the standardized Kuppuswamy scale. Regression models for count and binomial data were used to examine association of caste and class with experience of discrimination and response to discrimination.

Results

68% of women experienced discrimination. After adjusting for confounders, there was a consistent trend and association of discrimination with caste but not class. In comparison to General Caste, lower caste (OBC, SC/ST) women were more likely to 1) experience discrimination (OBC OR: 2.2, SC/ST: 4.1; p-trend: 0.01), 2) have a greater perceived discrimination score (OBC IRR: 1.3, SC/ST: 1.5; p-trend: 0.07), 3) accept discrimination (OBC OR: 6.4, SC/ST: 7.6; p-trend: < 0.01), and 4) keep to herself about discrimination (OBC OR: 2.7, SC/ST: 3.6; p-trend: 0.04).

Conclusion

The differential experience of discrimination by lower caste pregnant women in comparison to upper caste pregnant women and their response to such experiences highlight the importance of studying discrimination to understand the root causes of existing caste-based disparities.

Keywords: perceived discrimination, caste, socioeconomic status, rural India, social justice

Introduction

Discrimination is unequal treatment based on social structures that allow one group to maintain power and privileges over others (Krieger 1999). Perceived discrimination refers to distinct stressful life experiences of unfair treatment based on personal attributes such as race (Banks et al. 2006). The impact of perceived discrimination has been studied extensively in the U.S., where racial and ethnic minorities experience greater discrimination and adverse health outcomes (Pascoe and Smart Richman 2009; Williams and Mohammed 2009; Dolezsar et al. 2014; Schmitt et al. 2014). Similar to the U.S., where race significantly impacts socioeconomic status and health (Kochhar and Fry 2014; CDC 2016), caste may be an important determinant of discrimination and health in India.

Caste in modern India is considerably different from its origins and is the basis for the current affirmative action program, called the Reservation system. An understanding of India’s caste system and its evolution over time is necessary for the examination of caste-based discrimination. Historically, an individual’s jati was determined by the occupation of the family into which he/she was born; it could, albeit rarely, change over time (Vaid 2014). The term caste was introduced by a British ethnographer in 1901; while conducting a census of India, he consolidated more than 3,000 jatis into 7 castes and limited this classification to Hindus (Risley, Herbert Hope 1901). Caste classification in post-colonial India includes religious minorities, is considered to be rigid except through marriage, and has four categories, in the order of increasing social disadvantage: General Caste, Other Backward Caste (OBC), Scheduled Caste (SC), and Scheduled Tribe (ST). SC and ST castes are comprised of Dalit and Adivasi people, respectively (Thomas et al. 2013; Lancet 2014). Dalits were considered to be impure in ancient-Indian societies because their occupation involved butchering animals and disposing human waste. Dalits were prohibited from participating in Indian social life and were not to be touched, seen, or approached (Chalam 2007). Adivasis are the indigenous population of India. Unlike Dalits, who lived in the vicinity of other people, Adivasis typically resided in forests and rarely interacted with other groups. The third disadvantaged caste, OBC, was established to classify groups that were socially, economically, and educationally disadvantaged (Vaid 2014). Since its formation in 1955, OBC classification has further expanded to include additional disadvantaged castes in India (Vaid 2014). General Caste includes all people who do not belong to any of the other three castes (Deshpande 2003). 30.8% of India’s population belong to the General caste, 41.1% to OBC, and 28.2% to SC/ST (Directorate of Census Operations Gujarat 2014).

Caste relations in India and race relations in the U.S., while not interchangeable, share similarities (Slate 2011; Reddy 2016). Historically, Black Americans and SC are marginalized identities who are subjected to discriminative social norms (Haynes and Alagaraja 2016). While discrimination based on caste is outlawed in India, 93% of people across Northern India, including law makers, reported that they believed atrocities were still committed on SC members (Naval 2004). Of 565 villages studied across 11 states, 33% of villages have public health workers who refuse to enter SC people homes, 25% forbid SC milk buying, 73% do not allow SC to enter homes of other castes, and in 37.8% the children of SC families must sit separately in public schools (Thomas et al. 2013). Moreover, education rates are much lower in SC communities and life expectancy is 4 years less than non-Dalits (Thomas et al. 2013).

While the link between caste and poor health outcomes in India has been studied in the past, a PubMed search in July, 2017, using keywords “perceived discrimination” and “India” produced only six results. Of these, only two were based on research in India (Kuhlmann et al. 2014; Zieger et al. 2016), and none investigated the relationship of caste and discrimination. Existing literature indicates that caste is one of the strongest determinants of reproductive and child health outcomes (Sanneving et al. 2013). In rural India, the highest infant mortality is in SC and OBC communities (Singh et al. 2013). Although the cause of such caste health disparities can be multifactorial, perceived discrimination may play a role. Results from discrimination research conducted outside of India have found that discrimination is associated with preterm birth and low birth weight (Lauderdale 2006; Giurgescu et al. 2011; Earnshaw et al. 2013; Mendez et al. 2014). Further, a recent study found that women reporting experiencing perceived discrimination had higher late pregnancy evening cortisol and poorer self-rated health, and their infants had higher stress reactivity at six weeks old (Thayer and Kuzawa 2015).

Considering the paucity of literature on perceived discrimination in India and the significant role caste plays in health and socioeconomic inequality in India, we sought to measure perceived discrimination among pregnant women from rural India. We focused on pregnant women because pregnancy is a time of increased medical care. Understanding the experiences of low caste women during this critical period may provide insight into caste-based disparities in maternal and child healthcare and outcomes. We hypothesized that lower caste women would experience greater perceived discrimination than women of upper caste regardless of socioeconomic class.

Methods

Setting and Study Design

Included data are a subset from a prospective cohort study conducted in Anand, Gujarat, India, studying the peripartum experience of rural Indian women and examine the association of their child’s growth with psychosocial, biomedical, and sociocultural factors (n = 220)(Soni et al. 2014). Gujarat is located in the western most region of India and Anand district is located in the center of Gujarat state. More than two-thirds (69.7%) of Anand’s population resides in rural villages (Directorate of Census Operations Gujarat 2014).

Participant

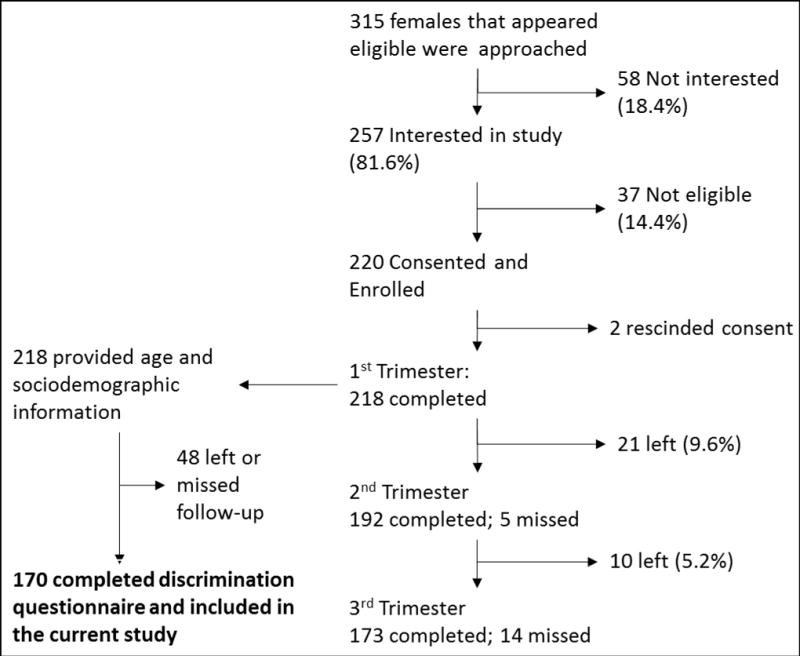

Participants were recruited between July 1, 2013 and June 30, 2014 in one of two ways. First, all patients seen at the OB/Gyn outpatient clinic at the tertiary care Shree Krishna Hospital (SKH), for an initial obstetric visit were approached by research coordinators and screened for eligibility. Second, government-sponsored Accredited Social Health Activists, who are responsible for developing and maintaining a census of all pregnancies in rural India, referred all newly pregnant women from their villages to the research staff at SKH. Eligibility criteria included: age between18–40 years, fetal estimated gestational age between 10w0d – 13w6d, understand Gujarati language, and have no plan to move from Anand for two years. Exclusions were: multiple gestation, surrogate carrier, conceived using assisted reproductive technologies, and chronic health conditions. Of the 220 women enrolled in the cohort study, 170 women responded to the discrimination questionnaire (details in Figure 1) and were included in this analysis.

Figure 1.

Participant flowchart for the prepartum timepoints of the prospective cohort study (right) and subsample for the discrimation study (left)

Data Sources

Standardized questionnaires, developed and validated by other studies were translated to Gujarati through professional translating services, and were administered by trained female research coordinators during the participant’s prenatal visits. Because these questionnaires were developed in markedly different communities than the study setting, we performed comprehensive cognitive response testing (Sousa and Rojjanasrirat 2011), a process in which all questionnaires were administered to three volunteers from the community who were in the SKH waiting areas. Volunteers were asked to describe their understanding of each question and to note aspects that were difficult to follow or made them feel uncomfortable. Two bilingual investigators reviewed the feedback from the volunteers and made edits to the Gujarati forms to improve the cultural appropriateness and understandability, while maintaining the intent of the questions.

Exposure

Caste

In our study, caste data was self-reported. We asked “What was your caste at birth?” The options given were General, OBC, SC, ST or other. Participants who reported their caste as ‘Other’, were asked to specify.

Socioeconomic class

We used the validated composite Kuppuswamy scale for classifying socioeconomic class by considering education level, household income, and husband’s occupation (Sharma 2012). Based on the univariate distribution, upper and upper-middle class were combined into one category, lower middle class remained distinct, and upper-lower and lower class were combined into one category thus yielding a three category variable.

Outcomes

Perceived discrimination

The nine-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) (Williams et al. 1997) was used to quantify perceived discrimination. Response options included 0: Seldom (never/less than once a year), 1: Sometimes (a few times a year/a few times in a month), and 2: Often (at least once a week/almost everyday). Scores could range from 0 to 18 with a higher score representing greater perceived discrimination. The reliability of EDS measured using Cronbach’s α yielded a scale reliability coefficient of 0.93 in the study sample.

Response to experiences of perceived discrimination

Two questions from the Experience of Discrimination (EOD) questionnaire assessed participants’ response to unfair treatment (Krieger et al. 2005). The first question asked if the respondent accepts unfair treatment as a fact of life or tries to do something about it. The second question asked whether the respondent, after being treated unfairly, talks to others about it or keeps the experience to herself.

Potential Confounders

Based on our a priori knowledge of factors affecting women’s experiences in rural Indian settings, we considered participants’ age, employment status, religion, and age difference of 5+ years with their spouse as potential confounders for the relationship of perceived discrimination with caste and socioeconomic class. These variables influence the frequency and scope of interactions for rural Indian women outside of their homes (Jejeebhoy and Sathar 2001).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed to evaluate differences in the distribution of age and socio-economic status characteristics of the participants across the three caste categories. Cuzick’s test for trends was used to assess statistically significant differences across the ordered groups (Cuzick 1985). The association of perceived discrimination and caste and class were evaluated using zero inflated negative binomial regression on the aggregate everyday discrimination score. Zero inflated negative binomial modeling was chosen over Poisson and negative binomial regression methods, because empirical distribution of the outcome data demonstrated over-dispersion and over-representation of zero. This modeling approach yields two separate effect estimates in the form of exponentiated beta coefficients with 95% confidence intervals: 1) odds ratio of reporting zero as an outcome and 2) incidence rate ratio, which are interpreted as count multipliers for the odds of reporting an increasing number of discrimination score. We built three separate models to examine the association of discrimination with caste and class: first model only included caste as an explanatory variable, second model only included class as an explanatory variable, and the third model included caste, class, and analytically selected confounders i.e. age and age difference with spouse. The confounders for third models were included if they produced a 10% or greater change in the effect estimates of any categories of caste and class. The association of caste and class with responses to discrimination was assessed using logistical regression models. Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was calculated for two separate models for caste and class, and for a third multivariable model that included both caste and class in addition to other confounders. In addition to 95% confidence intervals, statistical significance was assessed for trends across all models by using an observation-weighted linear polynomial test (Mitchell 2012). We were unable to test statistical interactions due to sparse data issues in certain interaction terms such as SC/ST participants in upper class and vice-versa.

Results

Of the 170 participants included in the analyses, 50 (29.4%) were of General Caste, 99 (58.2%) were of OBC, and 21 (12.4%) self-reported their caste as SC/ST (Table 1). On average, participants from lower castes were younger than General Caste women. Nearly an equal number of participants belonged to the three categories of class. Caste was closely associated with class, as well as education, income, and occupation. There was no discernible association between caste and working status, religion, or five years or greater age difference with spouse.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Indian Women Who Responded to Discrimination Questionnaire at Shree Krishna Hospital in 2014

| Self-Reported Caste (%)

|

p-value (trend)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total 170 | General 29.4 | OBC 58.2 | SC/ST 12.4 | ||

|

|

|

||||

| Age: mean (SD) | 165 | 26.7 (4.04) | 25.6 (4.3) | 23.4 (3.3) | 0.003 |

| Socioeconomic class | |||||

| Upper-Upper Middle | 57 | 62.0 | 20.2 | 28.6 | |

| Lower Middle | 47 | 20.0 | 27.3 | 47.6 | 0.001 |

| Upper Lower-Lower | 66 | 18.0 | 52.5 | 23.8 | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than 7 Grade | 24 | 2.0 | 19.2 | 19.1 | |

| Grade 7 – Grade 12 | 111 | 56.0 | 68.7 | 71.4 | <0.001 |

| More than High School | 35 | 42.0 | 12.1 | 9.5 | |

| Income | |||||

| < $0.50/person/day | 31 | 6.0 | 24.5 | 23.8 | |

| $0.50–1.25/person/day | 77 | 34.0 | 53.2 | 47.6 | <0.001 |

| > $1.25/person/day | 57 | 60.0 | 22.3 | 28.6 | |

| Husband Occupation | |||||

| Pro./Semi-Pro. | 31 | 27.1 | 17.7 | 4.8 | |

| Skilled Worker | 85 | 62.5 | 41.7 | 71.4 | 0.01 |

| Laborer | 49 | 10.4 | 40.6 | 23.8 | |

| Working for Pay | |||||

| No | 137 | 84.0 | 80.8 | 75.0 | NS |

| Religion | |||||

| Hindu | 147 | 88.0 | 84.9 | 90.5 | NS |

| Husband Age Difference | |||||

| > 5 years | 50 | 22.0 | 33.3 | 28.6 | NS |

OBC: Other Backward Caste; SC: Scheduled Caste; ST: Scheduled Tribe; Pro.: Professional; NS: not significant (> 0.05)

Based on cuzick’s test for trends to evaluate trend differences across the three caste ctegories

115 (67.6%) participants reported experiencing at least some level of discrimination on the EDS. The average discrimination score was 1.5 (SD: 2.7) for General Caste women, 3.2 (SD: 3.4) for OBC women, and 4.3 (SD: 3.9) for SC/ST women (p < 0.001). Results from zero-inflated negative binomial regression models are reported in Table 2. After adjusting for confounders, OBC women were twice as likely and SC/ST women were four times more likely than women of General Caste to report ever experiencing discrimination (p-value for trend = 0.01). By contrast there was no significant trend for increased odds of experiencing discrimination by women of lower socioeconomic class compared to those of upper socioeconomic class. Lower caste women had a 30% (OBC) and 50% (SC/ST) higher discrimination score in comparison to women of General Caste (p = 0.07). No discernible associations or trends were observed across different socioeconomic class categories with the sole exception of lower class women experiencing a 2.2 times greater odds of experiencing discrimination (95% confidence interval: 0.9 to 4.9).

Table 2.

Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial Regression Models for the Association between Perceived Discrimination and Caste and Class.

| Panel A represents odds ratio for reporting experience of any discrimination | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel B represents count multiplier for discrimination score

| ||||||||

| A: Non-zero outcome | B: Increasing count of discrimination score | |||||||

| unadj. OR | p* | adj.# OR | p* | unadj. OR | p* | adj.# OR | p* | |

|

|

||||||||

| Caste: General | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| OBC | 2.9 (1.4 to 5.9) | <0.01 | 2.2 (1.0 to 5.0) | 0.01 | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.7) | 0.07 | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 0.07 |

| SC/ST | 3.8 (1.3 to 11.4) | 4.1 (1.2 to 13.6) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | ||||

| SES: Upper/Upper Middle | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Lower Middle | 1.7 (0.8 to 3.8) | 0.01 | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.8) | NS | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.94 | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | NS |

| Upper Lower - Lower | 3.2 (1.5 to 6.9) | 2.2 (0.9 to 4.9) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | ||||

p-values are based on observation-weighted linear polynomial test to assess for trend across ordered categories of caste and class

based on multivariable adjustment of caste, class, age, and age difference with spouse. Collinearity between confounders was tested using variance inflation factor and tolerance and potential violation of multicollinearity assumption was ruled out.

Table 3 reports results from unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models that examined the association between caste, socioeconomic class, and responding to experiences of discrimination. After accounting for confounders, women of lower castes were consistently more likely to accept unfair treatment as a fact of life (p-trend < 0.01) and keep to themselves about it (p-trend= 0.04), compared to women of General Caste. Although lower class women were twice as likely to accept unfair treatment as fact of life (unadjusted OR: 2.4; 95% confidence interval: 1.1 to 5.3) than upper class women, this association disappeared after accounting for caste and other confounders. Similarly, there are no consistent trends across the socio-economic status categories for response to experiencing discrimination.

Table 3.

Results of Logistic Regression Models for Responses of Pregnant Women at Shree Krishna Hospital to Experience of Discrimination Questions: “If you have been treated unfairly do you usually:”

| A: Accept it as a fact of life | B: Keep to self about it | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unadj. OR | p* | adj.# OR | p* | unadj. OR | p* | adj.# OR | p* | ||

|

|

|||||||||

| Caste: General | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| OBC | 5.5 (2.1 to 14.1) | <0.01 | 6.4 (2.2 to 18.7) | <0.01 | 2.3 (0.9 to 6.2) | 0.12 | 2.7 (0.9 to 8.0) | 0.04 | |

| SC/ST | 4.5 (1.3 to 15.4) | 7.6 (1.9 to 30.1) | 2.3 (0.6 to 8.6) | 3.6 (0.9 to 15.2) | |||||

| SES: Upper/Upper Middle | Reference | Reference | |||||||

| Lower Middle | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.9) | 0.02 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.8) | NS | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.4) | 0.80 | 0.3 (0.1 to 1.0) | NS | |

| Upper Lower - Lower | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.3) | 1.2 (0.5 to 3.0) | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.7) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.9) | |||||

p-values are based on observation-weighted linear polynomial test to assess for trend across ordered categories of caste and class

based on multivariable adjustment of caste, class, age, and age difference with spouse. Collinearity between confounders was tested using variance inflation factor and tolerance and potential violation of multicollinearity assumption was ruled out.

Discussion

In our study, we found nearly two of three participants had experienced discrimination. We found a strong association between caste with ever experiencing discrimination and the intensity of discrimination. We also found that women of disadvantaged castes were substantially more likely to accept unfair treatment as a fact of life and keep to themselves about unfair treatment. These findings persisted even after accounting for socio-economic status and other possible confounders. By contrast, we did not find a strong or consistent link between socioeconomic class and perceived discrimination or response to unfair treatment. These findings underscore the significant role caste continues to play in the day-to-day lives and interpersonal interactions of Indian women regardless of their socioeconomic class.

The complex sociocultural construct of the caste system in India plays a crucial role in discrimination. (Deshpande 2003; Borooah 2005). As our results indicate, lower caste women are not only more likely to experience discrimination, but they are more likely to accept unequal treatment as a fact of life. Therefore, the lower caste women in our study appear to experience discrimination that is unacknowledged. This response to experiences of caste-related discrimination can be understood by learned helplessness theory, a process by which people exposed to uncontrollable situations learn that the outcomes of the situation are independent of their actions (Abramson et al. 1978). Such individuals believe that either they inherently lack the ability to control external circumstances (personal helplessness) or that the circumstances simply cannot be changed (universal helplessness). Those with personal helplessness have internal attribution and tend to fair worse in difficult situations, as they believe their actions will not make a difference. This apathy can lead to self-destructive thoughts and further impact maternal and child health (Tsirigotis et al. 2013, 2014). Our finding that SC/ST women were nearly eight times more likely to accept unequal treatment and three times more likely to not discuss their unfair experiences with others suggests that they may be at higher risk for developing attribution styles that further limit their ability to respond to discrimination. More studies are needed to understand how the development of attribution styles among low caste people is affected by their lifelong experience of being underprivileged and its related psychological and mental health cost.

Our finding that perceived discrimination is associated with caste but not socioeconomic class has important implications for the study of health inequalities in India at a broader level. Our results challenge the commonly made assumption that caste is a proxy for socioeconomic class and poverty when investigating health outcomes (Nayar 2007; Fenske et al. 2013). Although caste is closely linked with socioeconomic class, assuming that caste and socioeconomic class are interchangeable conflates these two important determinants of health and may masquerade the unique short and long-term risks experienced by lower caste people. Specifically, unlike class, which can change over a person’s lifetime if not across generations, caste is intransigent and therefore carries a lifelong burden of being underprivileged and its related psychological and mental health cost. Another important consideration for disentangling the differential association of caste and class with perceived discrimination is its implications for our understanding of the role caste plays in modern India. According to the Indian government, the sole purpose of caste classification in India is to accommodate the administration of the Reservation system, wherein education, employment, and social services are reserved in a predetermined quota for low-caste people (Vaid 2014). Our results suggests that caste based discrimination continues to persist in India and caste is a construct that may have a prominent role in the social fabric of modern India.

Our findings are based on a sample of pregnant women from a rural western Indian community and generalizations for the broader population should be made with caution. Our strategy to leverage local health workers’ presence in the community to recruit all newly pregnant women from the surrounding villages and providing free healthcare helps overcome barriers faced by lower caste and social class women. During pregnancy, women receive increased support and enjoy societal privileges compared to non-pregnant times. Therefore, it is possible that our findings underreport the extent of discrimination faced by rural Indian women who are not pregnant. If underreporting occurred, women of lower caste, who tend to be less likely to vocalize their complaints due to a more stringent upbringing, are more likely to underreport than upper caste women (Inman et al. 2015). Therefore, our results may underestimate the association of caste and discrimination. Nevertheless, this approach allows us to better understand the circumstances of a specific population at high risk for adverse health outcomes. EDS aggregate scores do not support analysis of the separate types of experiences that may lead to discrimination. Small sample size limits point estimate precision and precluded our ability to examine interaction terms. Future studies should investigate how intensities of discriminatory experiences varies for people of different caste and class and whether or not there is differential amounts discrimination experienced by people who are of low caste and upper class in comparison this to those of low caste and lower caste.

In conclusion, caste but not socioeconomic class is closely linked with perceived discrimination among pregnant women in rural India and their responses to unfair treatment. Given that 1) India’s maternal and child health outcomes are among the world’s worst, 2) India has one of the largest gender gaps globally, and 3) these pitfalls disproportionately impact those of lower caste, it is necessary to understand the experiences of low caste, pregnant women and identify opportunities for empowering low caste women to more effectively deal with unfair treatment as well as sensitize healthcare providers, particularly those who care for mothers and children, to the discriminatory experiences of low-caste women.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Deborah Plummer for her thoughtful comments on understanding discrimination within the context of historically disenfranchised populations.

Funding: This study was supported by 2013 University of Massachusetts Medical School Office of Global Health Pilot Project Grant. Contribution by co-authors was partially supported by TL1-TR001454 (to A.S.) and KL2TR000160 (to N.B.) from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, P60-MD006912-05 (to J.A.) from National Institute on Minority Health and Disparities, and Joy McCann Endowment (to T.M.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute if Health.

Footnotes

Ethical approval:

Consent for participation was obtained by trained interviewers prior to enrollment. Interviewers read the consent to participants in Gujarati, shared a single-page fact sheet about the study with them, and answered questions. Willing participants were asked to sign a separate consent form and a copy of the form was provided to the participants. Human Research Ethics Committee of HM Patel Center for Medical Care and Education at SKH reviewed the study and approved it. University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) Institutional Review Board reviewed the study and exempted it because of the approval by a local ethics committee in India and the absence of interaction of UMMS researchers with study participants or their identified data. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Jasmine Khubchandani, Apurv Soni, Nisha Fahey, Nitin Raithatha, Anusha Prabhakaran, Nancy Byatt, Tiffany A Moore Simas, Ajay Phatak, Milagros Rosal, Somashekhar Nimbalkar, and Jeroan J Allison report no conflict of interest.

References

- Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978;87:49–74. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH, Kohn-Wood LP, Spencer M. An examination of the African American experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Ment Health J. 2006;42:555–70. doi: 10.1007/s10597-006-9052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borooah VK. Caste, Inequality, and Poverty in India. 2005;9:399–414. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalam KS. Caste Based Reservations and Human Development in India. Sage Publications; New Delhi, India: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4:87–90. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande S. Contemporary India: A Sociological View. Penguin Books; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Directorate of Census Operations Gujarat. 2011 Anand District Census Handbook. New Delhi, India: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJM, Miller SB. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol. 2014;33:20–34. doi: 10.1037/a0033718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Rosenthal L, Lewis JB, et al. Maternal experiences with everyday discrimination and infant birth weight: a test of mediators and moderators among young, urban women of color. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenske N, Burns J, Hothorn T, Rehfuess EA. Understanding child stunting in India: a comprehensive analysis of socio-economic, nutritional and environmental determinants using additive quantile regression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurgescu C, McFarlin BL, Lomax J, et al. Racial discrimination and the Black-White Gap in adverse birth outcomes: A review. J Midwifery Women’s Heal. 2011;56:362–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R, Alagaraja M. On the Discourse of Affirmative Action and Reservation in the United States and India: Clarifying HRDs Role in Fostering Global Diversity. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2016;18:69–87. doi: 10.1177/1523422315619141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inman AG, Tummala-Narra P, Kaduvettoor-Davidson A, et al. Perceptions of Race-Based Discrimination Among First-Generation Asian Indians in the United States. Couns Psychol. 2015;43:217–247. doi: 10.1177/0011000014566992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Sathar ZA. Women’s Autonomy in India and Pakistan: The Influence of Religion and Region. Popul Dev Rev. 2001;27:687–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00687.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar R, Fry R. Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29:295–352. doi: 10.2190/M11W-VWXE-KQM9-G97Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, et al. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann AS, Galavotti C, Hastings P, et al. Investing in communities: Evaluating the added value of community mobilization on HIV prevention outcomes among FSWs in India. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:752–766. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0626-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet T. The health of India: a future that must be devoid of caste. Lancet. 2014;384:1901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS. Birth outcomes for Arabic-named women in California before and after September 11. Demography. 2006;43:185–201. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez DD, Hogan VK, Culhane JF. Institutional racism, neighborhood factors, stress, and preterm birth. Ethn Health. 2014;19:479–499. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2013.846300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MN. Interpreting and Visualizing Regression Models Using Stata. Stata Press; College Station, TX: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Naval TR. Legally combating atrocities on scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Concept Publishing Company; New Delhi, India: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nayar KR. Social exclusion, caste & health: A review based on the social determinants framework. 2007;126:355–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS. The Ethnicity of Caste. Anthropol Q. 2016;72:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Risley Herbert, Hope S. Census of India, 1901. Calcutta: 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Sanneving L, Trygg N, Saxena D, et al. Inequity in India: the Case of Maternal and Reproductive Health. Glob Heal …. 2013;1:1–31. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, Garcia A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:921–48. doi: 10.1037/a0035754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R. Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale–revision for 2011 and formula for real-time updating. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:961–2. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0679-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Kumar A, Kumar A. Determinants of neonatal mortality in rural India, 2007–2008. PeerJ. 2013;1:e75. doi: 10.7717/peerj.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slate N. Translating Race and Caste. J Hist Sociol. 2011;24:62–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6443.2011.01389.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soni A, Fahey N, Raithatha N, et al. Understanding Predictors of Maternal and Child Health in Rural Western India: An International Prospective Study; APHA 142nd Annual Meeting and Expo; New Orleans, LA, USA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:268–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer ZM, Kuzawa CW. Ethnic discrimination predicts poor self-rated health and cortisol in pregnancy: Insights from New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Rita S, Kumar J. A Note on Caste Discrimination and Human Rights Violations. Serials. 2013;93:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Tsirigotis K, Gruszczynski W, Lewik-Tsirigotis M. Manifestations of Indirect Self-destructiveness and Methods of Suicide Attempts. Psychiatr Q. 2013;84:197–208. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9239-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsirigotis K, Gruszczyński W, Tsirigotis-Maniecka M. Gender Differentiation in Indirect Self-Destructiveness and Suicide Attempt Methods (Gender, Indirect Self-Destructiveness, and Suicide Attempts) Psychiatr Q. 2014;85:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s11126-013-9283-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid D. Caste in Contemporary India: Flexibility and Persistence. Annu Rev Sociol. 2014;40:391–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Yu, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieger A, Mungee A, Schomerus G, et al. Perceived stigma of mental illness: A comparison between two metropolitan cities in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58:432. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.196706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]