Abstract

Objective

This study investigated the feasibility of a novel blended (face-to-face and computer-based) group intervention for the reduction of depressive symptoms in major depression.

Design

Patient-centred uncontrolled interventional study.

Setting

University setting in a general community sample. A multimodal recruitment strategy (public health centres and public areas) was applied.

Participants

Based on independent interviews, 26 participants, diagnosed with major depressive disorder (81% female; 23% comorbidity >1 and 23% comorbidity >2), entered treatment.

Intervention

Acceptance and mindfulness based, as well as self-management and resource-oriented psychotherapy principles served as the theoretical basis for the low-threshold intervention. The blended format included face-to-face sessions, complemented with multimedia presentations and a platform featuring videos, online work sheets, an unguided group chat and remote therapist–patient communication.

Main outcome measures

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale and the 12-item General Health Questionnaire.

Results

Large to very large within group effect sizes were found on self-reported depression (F (2, 46.37)=25.69, p<0.001; d=1.80), general health (F (2,46.73)=11.47, p<0.001; d=1.32), personal resources (F (2,43.36)=21.17, p<0.001; d=0.90) and mindfulness (F (2,46.22)=9.40, p<0.001; d=1.12) after a follow-up period of 3 months. Treatment satisfaction was high, and 69% ranked computer and multimedia use as a therapeutic factor. Furthermore, participants described treatment intensification as important advantage of the blended format. Half of the patients (48%) would have preferred more time for personal exchange.

Conclusion

The investigated blended group format seems feasible for the reduction of depressive symptoms in major depression. The development of blended interventions can benefit from assuring that highly structured treatments actually meet patients’ needs. As a next step, the intervention should be tested in comparative trials in routine care.

Trial registration number

DRKS00010894; Pre-results.

Keywords: blended therapy, blended group therapy, online interventions, group therapy, depression, therapeutic factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first clinical study on blended group therapy (bGT) for major depression. This innovative intervention combines two low-intensity psychosocial interventions, recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Participant selection was based on a multimodal recruitment strategy and comorbidity was high. Data on adverse effects are provided.

This is the first study to apply standardised measures of client satisfaction and system usability in bGT. Additionally, it provides a detailed view on participants’ appraisals of the new format.

The study entails a conceptual replication of previous findings on subjectively perceived therapeutic factors.

The uncontrolled study design and the university setting restrict the interpretability of results.

Introduction

Depression presents a relevant public health concern and imposes high costs on society as well as on health systems.1 Therefore, research priorities include health policy and system research, in particular, how to deliver cost-effective interventions in a low-resource context.2 3 Psychological online interventions have been found effective in reducing common mental health disorders, for example, depression4 and anxiety,5 in such low-resource contexts.

Online interventions offer many advantages; they can provide access to evidence-based treatments and patients can work through the intervention whenever they want.6 Usually, anonymity is preserved as patients participate at distance, resulting in low-social barriers and low risk of stigmatisation.7 From a health suppliers perspective, online interventions guarantee standardised treatments and show good scalability, which has led to the launch of the first online clinics.8 9 Internet-based interventions can also help with bridging waiting times10 or enhance treatment effects during aftercare.11 At the same time, online interventions do not fit all patients’ needs (eg, need for more personal contact or diverging preferences). Consequently, classical face-to-face therapy will remain an important basis of mental healthcare. That being said, tools and methods developed in online therapy can be integrated into various forms of face-to-face therapy.12

Due to the variety of possible combinations, it remains difficult to define blended interventions concisely. van der Vaart and colleagues13 describe blended therapy as ‘[…] a combination of online and face-to-face therapy, in which online sessions replace or substitute some (parts) of the sessions with a health professional […]’. According to Kooistra and colleagues,14 the combination of both intervention strategies should merge into one integrated treatment format. In our study’s context, new media was also used as a supportive in-session tool (eg, multimedia presentations and videos). Thus, we define blended therapy as an integrated combination of face-to-face sessions with computer or application support. It aims at improving the delivery of evidence-based therapy methods and results in a possible acceleration or intensification of treatment. The online part of blended interventions often entails psychoeducation, online exercises and remote therapist feedback on accomplished exercises, as well as mobile diaries or monitoring.15 Interventions are usually delivered via online platforms16 or applications for mobile phones.17

Blended therapy is at an early stage of research, even though first studies date back to the 1980s and 1990s.18–20 At that time, computer support had been found to be useful in the treatment of depression, anxiety or obsessive compulsive disorders.20 However, these early studies do not adequately account for the rapid development that modern technologies have undergone, and user behaviour has changed dramatically since then. When examining more recent literature, good acceptability and compatibility with standard treatments are found.21 Additionally, computer-assisted programmes may well shorten treatment duration while maintaining observed treatment effects.22 In Europe, research on blended therapy, currently is on the rise, as a multicentre study (E-COMPARED) investigates possible time savings in routine care.23 From a therapy process perspective, Månsson and colleagues16 suggest that blended interventions could foster adherence to evidence based-treatment rationales, because the structure provided by blended therapy might prevent therapists from so called therapist drift.24 Regarding the implementation of blended therapy, the Netherlands seems to be Europe’s most promotive nation.25 According to Netherlands’ leading software provider (Minddistrict), more than 17 000 professionals and 120 000 patients are currently using some of their blended services.26

With little exceptions, research on blended interventions has its primary focus on individual therapy and little is known about the potential for group treatments. As it is a recommended treatment in health guidelines and national health policies,27 28 group therapy has various applications in inpatient and outpatient clinics.29 For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence30 recommends group cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) for people with mild to moderate depression who decline other low-intensity psychosocial interventions, such as computerised CBT. Therefore, the integration of computer support and face-to-face group sessions might result in an optimised treatment, in which personal contact is preserved. Existing blended group therapy (bGT) studies reveal high acceptability for the treatment of anxiety disorders and suggest possible savings of therapist time.31–33 To achieve savings, typical standard treatments (12–14 session) are shortened by 33%–57% (6–8 sessions). Apart from potential savings, bGT allows new ways of therapist-to-client and client-to-client interaction, such as online supervision of homework tasks or gamification.34

Literature on bGT for depression remains scarce, as there do not exist any published articles prior to our first proof of concept study.35 Due to the demand for low-threshold treatments,36 we designed a CBT-based psychoeducational intervention entailing principles of resource-oriented psychotherapy and self-management therapy. Resource-oriented psychotherapy focuses on current concerns and tries to strengthen personal skills in order to achieve set goals.37 Self-management therapy has a long tradition in the treatment of depression,38 and elements such as behavioural goal setting or activity monitoring are frequently applied in blended interventions.39 40 Finally, psychoeducational cognitive-behavioural group therapy has recently been applied in a stepped care service model41 within the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme. In our first study,35 high treatment effects were observed in an adult sample, exhibiting a variety of unspecified depressive symptoms. Further, participants rated online and multimedia elements as equally relevant as group experience or specific CBT techniques. In an open evaluation, 25% freely described online and multimedia support as a therapeutic factor. However, the absence of a systematic diagnostic procedure and the lack of standardised measures (eg, client satisfaction and system usability) restrict the generalisability of findings.

The present study addresses these limitations by applying the developed blended group intervention to a sample of clinically depressed adults, and by evaluating its usefulness in a more structured and standardised way. Moreover, we analysed system usage and corresponding changes over the course of time. Lastly, the study provides a detailed view on participants’ appraisals of the new format.

Methods

Procedure

The clinical one-arm interventional study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ethical Review Board, University of Vienna, Ref-Nr:00194) and registered at the German clinical trial register (DRKS-ID: DRKS00010894). Eligible persons were called and informed consent was obtained verbally by two independent interviewers. Subsequently, the complete Mini-DIPS (Diagnostic Interview for Psychological Disorders) was applied for study inclusion or exclusion.42 The Mini-DIPS is a 30 min short version of the German DIPS,43 based on International Classification of Diseases 10th revision depression criteria. Ten days before the intervention started, eligible participants (n=26) were required to complete an online questionnaire of self-report measures. Sessions were held in a double trainer format by two trained and supervised psychologists (VS and IL), both in the final year of their Master studies of clinical psychology. Both trainers had prior experience with conducting group therapy in clinical settings. Sessions took place in a specially equipped seminar room at the University of Vienna, Faculty of Psychology (Department of Applied Psychology: Health, Development and Promotion). At the beginning of the first group session, written informed consent was signed by all participants. One week after the intervention ended, an online postevaluation questionnaire was completed and follow-up data were obtained 3 months later.

Intervention

The treatment comprised a 7-week intensive CBT-based psychoeducation and self-management group intervention, in which personal sessions (90 min) alternated with online exercises and remote therapist feedback. CBT-based key techniques eclectically entailed mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive strategies for negative thoughts, as well as a special emphasis on time management and self-management and minor elements of positive psychology. The intervention focused on the reduction of depressive symptoms and aimed at increasing personal resources and self-management abilities. We carefully regarded best practice guidelines for empirically supported CBT group treatments of depression (eg, psychoeducation, behavioural goal setting, cognitive restructuring, relapse prevention and double trainer setting) during the design of the intervention.44 Online modules were made accessible via a secure web-based non-profit environment (Moodle with Secure Sockets Layer Virtual Private Network (SSL VPN) access), featuring videos, online work sheets, an unguided group chat and remote therapist–patient communication. Accomplishing one online session took approximately 50–70 min (34 min of weekly videos included). The platform automatically tracked personal log data for each participant and week. Group sessions were supported by multimedia, for example, psychoeducational short clips and PowerPoint presentations. Participants were also able to logon the platform after the group sessions had ended. The basic intervention is described comprehensively in our preceding study.35 Improvements are in regards to the psychoeducation section and the weekly diary as well as putting more emphasis on cognitive restructuring techniques. Detailed information on weekly modules is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Group sessions and computer and multimedia elements of the intervention

| Week | Group session | Computer and multimedia elements |

| Preassessment | Worksheet 1 Video 1 |

|

| C.1 | Opening and information about intervention and online platform; psychoeducation on depression; introduction to the current concerns concept; instruction for current concerns diary and relaxation | PPT-presentation Worksheet 2 Video 2 |

| C.2 | Discussion of homework assignments; psychoeducation on human perception and cognitive biases; discussion on frequent cognitive distortions; psychoeducation on acceptance and mindfulness principles; instruction for the “Thoughts and mindfulness” diary task | PPT-presentation Video 3 Mobile phone diary* |

| P.3 | Discussion of homework assignments; psychoeducation on human memory and learning processes; exercise on cognitive restructuring; introduction to “Happiness” diary and activity list | PPT-presentation Worksheet 3 Video 4 and 5 Mobile phone diary* |

| P/A.4 | Discussion of homework assignments; psychoeducation on psychological motivation theories and goal setting, with emphasis on Vroom’s VIE-theory (1964); group exercise on “SMART” goal setting and instruction for Goal Attainment Scaling | PPT-presentation Online Goal Attainment Scaling with feedback |

| Break | ||

| A.5 | Revision of sessions 1–4; psychoeducation on self-regulation and self-control; group exercise on strengths and weaknesses profile; discussion and refinement of individual goals; instructions for weekly diary task | PPT-presentation Contract with myself-worksheet 4 Mobile phone diary* |

| A.6 | Discussion of homework assignments; psychoeducation on time management, realistic time scheduling; group exercise “Time-thieves”; group discussion on practical aspects of time management and prioritisation; introduction to specific time management methods; group exercise “Stress traffic light” | PPT-presentation Worksheet 5+ Video 5 Mobile phone diary* |

| M.7 | Revision of sessions 5–7; psychoeducation on slow and problematic change patterns and handling of setbacks; group discussion on problematic change and relapse prevention | PPT-presentation |

| Postassessment |

*Mobile phone diary, participants were free to choose between a mobile phone diary or a handwritten diary.

Letters C to M, treatment stages (C, contemplation, P, preparation, A, action, M, maintenance); PPT-presentation, in-session PowerPoint presentation; VIE, Expectancy Instrumentality Valence - Theory.

Participant recruitment and selection

The study was advertised online (eg, www.depression.at) and by handing out flyers in public health centres and populated public areas, such as urban pedestrian areas in Vienna. All those interested were invited to visit the study web page and to fill out an online participation form. Recruitment ended after sufficient participants had been acquired.

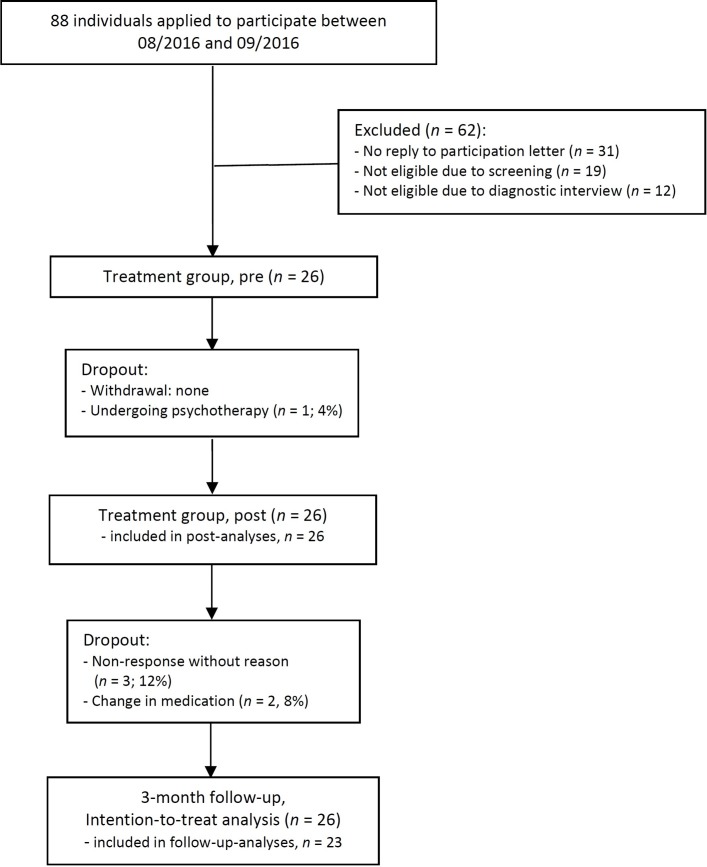

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two independent psychologists with clinical experience conducted the diagnostic interviews. Participants aged between 18 and 65 years, familiar with the use of personal computers and suffering from mild to moderate levels of major depression and/or dysthymia and/or mild to moderate comorbid anxiety were eligible for the study. According to clinical judgement, participants were excluded if they suffered from severe depression (≥7 criteria, including main symptoms), severe anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, severe psychiatric and psychotic conditions, substance abuse, suicidal ideation or if they exhibited low-German language and/or computer skills. Participants were also excluded if they were currently undergoing psychotherapy. Psychiatric medication was tolerated, but had to be kept constant for at least 3 months prior to study onset. Figure 1 presents the flowchart, demonstrating the recruitment and research procedure in detail.

Figure 1.

Study’s flow chart.

Measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome, reduction of depressed mood, was measured by the short form of the German translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale.45 This questionnaire assesses depression associated emotions and motor functions, as well as interactive, cognitive and somatic symptoms on a 16-item 4-step Likert scale. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depression and the German version’s cut-off value (CES-D >17) has high discriminative validity.45 The reliability of the CES-D has been shown to be excellent.46 Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.84.

Secondary outcome measures

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)47 was selected to assess the degree of self-reported psychological distress. Items are rated on a 4-step bi-modal scale (0-0-1-1) with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological distress. The GHQ-12 has shown satisfactory reliability48 and good intercultural validity.49 A cut-off of >1 served as a conservative measure with highest sensitivity and specificity in the literature.50 Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

The German ‘Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Ressourcen und Selbstmanagementfähigkeiten – Gesamtressourcen’ (FERUS, Questionnaire for the Assessment of Resources and Self-Management Abilities—common resources),51 consisting of the subscales ‘coping’, ‘self-awareness’, ‘self-efficacy’, ‘self-verbalisation’ and ‘hope’ (44 items, 7-point Likert scale), was applied for the assessment of personal resources. Higher scores represent higher levels of self-rated personal resources. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha of the total resources was 0.95.

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)52 assesses the frequency of mindful states, with higher levels indicating greater mindful awareness (15 items, 6-point Likert scale). We used a 6-item short version of the German MAAS53 and Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.83.

Client satisfaction and system usability

Usability of online and multimedia elements was assessed by the System Usability Scale (SUS).54 The SUS is a technology-neutral robust tool for assessing the quality of a given user interface. Empirically derived cut-off scores are graded from SUS >85.5 (excellent usability) to SUS >71.4 (good usability) and SUS >50.9 (acceptable usability) on a 10-item 5-point Likert scale.55 Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.85.

Participants’ overall satisfaction with the treatment was measured by the German version (ZUF-8)56 of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8).57 This widely used questionnaire addresses several aspects of service satisfaction and is based on an 8-item 4-point Likert scale. In this study Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Appraisal of new media elements, applicability and process aspects

Appraisal of new media elements, applicability and process aspects of the intervention were assessed by a self-designed questionnaire (55 items) at post-treatment. The questionnaire comprised nine items on intervention elements, six items on specific functions (eg, online platform), six items on satisfaction and perceived efficacy of the intervention, one ranking of perceived therapeutic factors,35 16 items on optimal blend, intensity and duration,13 nine items on mode of delivery (face-to-face or online)13 and eight items on perceived (dis)advantages of blended therapy.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS V.24.58 Significant prechanges to follow-up changes were analysed by linear mixed models, with restricted maximum likelihood estimation and compound symmetry as covariance type. Missing values on outcome measures were analysed in agreement with the intention to treat principle (ITT). Individual predifferences to follow-up differences served as basis for the reliable change indexes (RCI)59 and we used internal consistency as a measure for RCI reliability,60 resulting in a reliable change criterion of 7.22 scale points for the CES-D and 2.62 scale points for the GHQ-12. Additionally, participants were deemed to have undergone clinically significant improvement (CSI) when simultaneously exhibiting reliable change and scoring below CES-D or GHQ-12 post measurement cut-off (CES-D ≤17; GHQ-12 >1). Within-group effect sizes were calculated with pooled SD and reported in Cohen’s d.61 Power analysis was carried out using G*Power,62 resulting in an estimated sample size of n=22, for a conservative medium within-subjects effect size of d=0.65 (alpha-error α=0.05, power β=0.90). Differences in appraisals of intervention elements (see the Appraisal of new media elements and usage data section) were calculated by t-tests (comparing against grand average), and for intervention applicability (Questions 2 and 3 in the Applicability of the blended intervention section) and process aspects (see the Process aspects section) paired t-tests were applied.

Results

Sample characteristics

There were no dropouts during the treatment period, but three participants did not fill out the follow-up evaluation. Two patients reported changes in medication and one patient commenced psychotherapy. According to ITT principles, those patients remained in the analyses. According to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines, detailed information on participants’ flow can be gained from figure 1. Women constituted the majority of the sample (81%) and education was high (54% tertiary education). Participants’ age ranged from 23 to 51 years (M=33.9, SD=7.5). A comprehensive overview of participant characteristics can be gained from table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic, behavioural and clinical characteristics of the study sample at pretreatment (n=26)

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 33.9 (7.5) |

| Gender, female, n (%) | 21 (81) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| ≥ 9 years (compulsory school) | 3 (12) |

| ≥ 12 years (A level) | 9 (34) |

| ≥ any tertiary education (eg, university) | 14 (54) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Full time | 11 (42) |

| Part time | 7 (27) |

| Currently none | 8 (31) |

| Current psychopharmacological treatment, n (%) | 3 (12) |

| Prior psychotherapeutic treatment, n (%) |

14 (54) |

| Computer experience, n (%) | |

| Daily use | 22 (85) |

| Few times a week | 4 (15) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Major depression (F32.0 or F32.1) | 26 (100) |

| + Double depression (F32.0 or F3 2.1+F 34.1) | 4 (15) |

| + Generalised anxiety disorder (F41.1) | 4 (15) |

| + Social anxiety disorder (F40.1) | 3 (12) |

| + Panic disorder (F41.0) | 2 (8) |

| + Specific phobia (F40.2) | 2 (8) |

| + Hypochondriasis (F45.2) | 1 (4) |

| Comorbidity (participants fulfilling two or more diagnostic criteria) | 12 (46) |

| 1 Comorbidity | 6 (23) |

| ≥ 2 Comorbidities | 6 (23) |

Primary and secondary outcome measures

All outcome measures indicated significant changes and effect sizes were large to very large (see table 3). For the primary outcome measure CES-D, a statistically significant reduction of self-reported depressive symptoms was found, F-value of F (2, 46.37)=25.69, p<0.001. Regarding secondary outcome measures, self-reported psychological distress, assessed by the GHQ-12, significantly decreased F (2,46.73)=11.47, p<0.001. Furthermore, personal resources (FERUS) significantly increased, F (2,43.36)=21.17, p<0.001, as well as the frequency of mindful states (MAAS), F (2,46.22)=9.40, p<0.001. At follow-up, a proportion of 70% of patients exhibited CSI for depressive symptoms and CSI for general health was observed in 75%. One participant deteriorated reliably (4%). Detailed information on observed means, SD, effect sizes and reliable change is depicted in table 3.

Table 3.

Means, SD, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and reliable change for primary and secondary outcomes

| N | Estimated means (SD) | Follow-up | Effect sizes (estimated means) |

Reliable change | |||

| Pre | Post | Pre-effect size to follow-up effect size | Pre-RCI to post-RCI (CSI) | PreRCI to follow-up RCI (CSI) | |||

| CES-D | 26 | 24.58 (6.51) | 14.19 (6.73) | 13.28 (6.06) | 1.80 (1.13 to 2.41) | 69 (65) | 70 (70) |

| GHQ-12 | 26 | 5.50 (2.25) | 2.00 (3.11) | 2.05 (2.94) | 1.32 (0.70 to 1.89) | 65 (65) | 75 (75) |

| FERUS | 26 | 134.54 (25.94) | 156.04 (25.22) | 157.52 (25.31) | 0.90 (0.31 to 1.45) | – | – |

| MAAS | 26 | 3.29 (0.78) | 4.05 (1.01) | 4.25 (0.93) | 1.12 (0.52 to 1.68) | – | – |

SDs and 95% CI ranges are shown in parentheses.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (cut-off >17); CSI, clinically reliable improvement; FERUS, Questionnaire for the Assessment of Resources and Strengths; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire (cut-off >1); MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; RCI, Reliable Change Index.

Client satisfaction and system usability

Usability of online and multimedia elements, assessed by the SUS,54 unveiled an average usability of 85.3 (SD=14.49) on a 100-point scale. Highest quality ratings (excellent usability, SUS >85) were given by 56% and another 24% of participants rated the platform usability as ‘good’ (SUS >72). One participant (4%) rated the usability as ‘low’ (SUS <51). Clients’ service satisfaction was measured by the CSQ-8,57 and average satisfaction was 27.4 (SD=3.9) of 32 possible scale points, indicating ‘good’ client satisfaction. On item level (M=3.43), an average rating of 3 indicates clients being ‘somewhat satisfied’ and a rating of 4 scale points translates into ‘very satisfied’. Here, 84% of participants gave ratings ≥3 scale points.

Appraisal of new media elements, applicability and process aspects

To explore participants’ retrospective perception of new media elements, as well as applicability and process aspects of the blended format, an additional self-designed questionnaire was applied.

Appraisal of new media elements and usage data

The results in table 4 show that computer and multimedia support were generally described as helpful (M=5.16 on a 6-step Likert-type scale). Almost half of the participants described in-session multimedia use, between session communication with the therapist, weekly psychoeducational videos and the online platform as very helpful, while a smaller proportion found them of little or no help. Interestingly, participants described group interaction as marginally less relevant compared with computer and multimedia. However, the only clear deviation from average was a lower rating for the unguided discussion forum. Table 4 also provides descriptive statistics on logins and downloads, where a continuous decrease in activity can be identified over the course of the treatment.

Table 4.

Appraisal of intervention elements and usage data (n=26)

| Intervention elements | Average | --- | -- | - | + | ++ | +++ |

| New media in general | 5.16 | – | 4 | – | 24 | 20 | 52 |

| Weekly group sessions | 5.40 | – | – | – | 16 | 28 | 56 |

| In-session multimedia | 5.08 | – | 4 | 4 | 12 | 40 | 40 |

| Between session communication with therapist | 5.08 | – | 4 | 4 | 24 | 20 | 48 |

| Weekly psychoeducational videos | 4.88 | 4 | – | 8 | 20 | 28 | 40 |

| Online platform | 4.8 | – | 8 | 12 | 12 | 28 | 40 |

| Group interaction | 4.64* | – | – | 4 | 28 | 36 | 32 |

| Discussion forum | 3.52† | – | 4 | 48 | 40 | 8 | – |

| Usage data | OS 1 | OS 2 | OS 3 | OS 4 | OS 5 | OS 6 | OS 7 |

| Average logins per week (per module) | 5.0 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.8 |

| Average downloads of work sheet/week | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | – |

| Average downloads of in-session slides/week | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Average logins during follow-up period | 4.5 |

--- not at all helpful (%); -- not helpful (%); - of little help (%); +somewhat helpful (%); ++helpful (%); +++very helpful (%).

*Tentatively significant.

†Highly significant.

OS, online session.

Applicability of the blended intervention

Table 5 depicts participants’ appraisals of the blended format and the influence of computer support on therapeutic process aspects in general, as well as preferred treatment duration. The majority (84%) stated that they would not leave out computer support and that this support has the potential to improve (80%) and intensify group therapy (72%). For our participants, blending best fitted the needs of training-alike groups. Here 96% agreed, that blended interventions could help improve and intensify (88%) existing rationales. The applicability rating of blended interventions for individual therapy was clearly less positive (48%), while prior therapy experience (54%) did not predict this appraisal (r=0.116, p=0.580). With a median of 12–15 sessions, preferred treatment duration was 50%–100% higher than the actual treatment duration (7 weeks).

Table 5.

Applicability of the blended intervention and treatment process aspects (N=26)

| Applicability of the blended intervention | Yes (%) | No (%) | P values |

| (1) Would you prefer to leave out computer and multimedia elements? | 16 | 84 | |

| (2) Do you think technology could help to improve group trainings? | 96 | 4 | |

| … to improve group psychotherapy? | 80* | 20 | 0.043 |

| …to improve individual psychotherapy? | 48*** | 52 | 0.000 |

| (3) Do you think technology could help to intensify group trainings? | 88 | 12 | |

| … to intensify group psychotherapy? | 72 | 28 | 0.103 |

| (4) Would you like to continue this treatment? | 88 | 12 | |

| (5) Optimal number of group sessions (MD) | 12 – 15 | ||

| Treatment process aspects | Yes (%) | Neutral (%) | No (%) |

| Used contents resulted in too little flexibility | 16 | 24 | 60 |

| There was too much structure | 20 | 24 | 56 |

| There was too much information | 16 | 32 | 52 |

| I would have preferred more time for talking and exchange | 48 | 32 | 20 |

*P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Process aspects

Statements on process aspects of the intervention entailed issues regarding perceived flexibility, structure, information and group interaction (table 5). A small proportion of investigated participants perceived applied computer and multimedia support as restricting or hindering (16%–20%). With a proportion of one quarter to one third, a group of indecisive participants existed. The 48% of participants expressed a desire for more group interaction and discussion time. In the ranking of subjectively perceived therapeutic factors, 69% of participants (rank 4 of 21) described in-session and intersession computer and multimedia use as an important therapeutic factor (table 6).

Table 6.

Top 10 ranking of subjectively perceived therapeutic factors (n=26)

| Rank | Therapeutic factor | n counts | % of all participants |

| 1. | Weekly lectures | 23 | 89 |

| 2. | Increase of positive thoughts | 20 | 77 |

| 3. | Restructuring of negative thoughts | 19 | 73 |

| 4. | Computer and multimedia use | 18 | 69 |

| 4. | Trainer (social and professional skills) | 18 | 69 |

| 6. | Group (coherence and interpersonal learning) | 17 | 65 |

| 6. | Positive activities | 17 | 65 |

| 8. | Reflexion | 16 | 62 |

| 9. | Mindfulness exercises | 14 | 54 |

| 9. | Exercises on resources and strengths | 14 | 54 |

n counts, number of counts associated with a specific factor; % of all participants, proportion of all participants.

Discussion

This feasibility study presents a user-centred evaluation of a recently developed blended group intervention for the reduction of depressive symptoms in major depression. Results indicate a high fit between psychological groups and blended components in terms of client satisfaction, system usability and the perceived relevancy of supportive computer and multimedia elements. Besides the standardised assessment of system usability and client satisfaction, the study entails a detailed view on blended elements, including possible improvements.

Corresponding primary outcome measures of the study indicate substantial effects on self-reported depressive symptoms and on general health. Compared with other psychoeducational group CBT interventions,41 observed reductions of self-reported depressiveness and rates of CSI can be classified as high. According to resource-oriented psychotherapy principles,39 51 participants also reported strengthened personal resources and self-management abilities (see the Primary and secondary outcome measures section). Results were maintained over a 3-month follow-up period. There was no withdrawal and only one participant deteriorated reliably (4%). These findings support prior literature on blended therapy,16 32 and underpin the potential of technology for psychological group interventions.

Regarding client satisfaction and system usability, participants provided positive evaluations of the investigated blended group format. For example, most patients stated that they would not leave out technology and that computer and multimedia support could help to improve existing treatments. Even though more than half of the patients had received prior therapy, the appraisal was less positive for individual therapy (cf the Applicability of the blended intervention section). This finding can be explained by a possible sceptical preconception and lack of opposite experience.14 It might also reflect patients’ perception of different requirements of the two settings. However, when compared with a concept study on blended individual therapy,40 system usability (SUS) and client satisfaction scores (CSQ-8) of the investigated group intervention were around one SD above. As blended learning originates from educational groups (eg, teaching or corporate trainings),63 interventions with more training-alike character may be particularly feasible for computer and multimedia support. This assumption is reflected by more positive appraisals for the improvement of training-alike interventions, compared with the improvement of classical group therapy (cf. the Applicability of the blended intervention section). However, the positive appraisal of treatment intensification between those forms of delivery did not differ significantly.

The investigated intervention entailed a variety of different computer and online elements. The online discussion forum and remote patient-to-therapist communication have setting-specific relevancy as they open up additional pathways for client-to-client and client-to-therapist interaction in group therapy. While remote patient-to-therapist communication was easy to install and described as important, the unguided online discussion forum was of less relevance for our patients. According to positive findings in online chat group and gamification studies,34 64 we conclude that online group interaction in blended interventions should either be guided by a therapist,65 or include other incentives to increase usage and perceived relevancy. During debriefing, some patients also explained, that their need for group interaction was satisfied by the weekly reunions.

Consistent with prior results, participants related in-session and intersession computer and multimedia use to the therapeutic success of the intervention (table 6). In our first study,35 25% of participants freely described computer support as a therapeutic factor. The direct ranking presented in this study yielded a notably higher proportion of agreement and can be interpreted as a conceptual replication of previous results. Additionally, treatment intensification was described as an important advantage. Results from a forthcoming qualitative article on patients’ experiences with the blended group format support present findings (personal communication by Schuster Raphael, November 201766). Regarding the interpretation, patients’ appraisals might best be conceptualised as the description of a catalytic effect, which possibly fosters other established therapeutic factors, such as imparting information29 or motivational clarification.37 Even though first results from comparative studies are promising,67 68 future research has to determine, if patients’ positive appraisals translate into superior effects of blended therapy in routine care. Still, from a product development perspective, patients’ connection of blended elements with treatment success can be seen as an important success criterion.

Findings regarding process aspects of the blended group format revealed important patient preferences. Many currently conducted studies on blended therapy investigate possible savings of therapist time by reducing the number of sessions (23, 31–33). From an economical point of view, potential time savings are inherently appealing for some mental healthcare stakeholders.25 69 On the other hand, short interventions might entail certain risks, such as a weakened patient-to-therapist bonding.13 eHealth experts therefore emphasise the need for participatory research and the importance of target audience’s perceptions when designing new treatments.70 71 As for that matter, the majority of our sample retrospectively would have preferred more group sessions (12–15 sessions) and half of our sample required more time for group interaction during each session (cf. the Applicability of the blended intervention section). Development and future uptake of blended interventions may therefore benefit from assuring that highly structured or time-efficient treatment strategies actually meet the expectations of addressed patients in a particular care setting.

Assessed objective usage data revealed a constant decrease of web page logins and downloads (cf. the Appraisal of new media elements and usage data section). Whether this tendency indicates a relevant reduction of motivation to persist with the intervention is unclear, as satisfaction with the intervention was high and usage patterns in the first weeks can be described in terms of exaggerated activity. For example, we provided one work sheet per week for download, but the actual number of downloads was reasonably higher. In this context, Yardley and collegues71 critically reflect on current approaches to validly conceptualise engagement by analysing log files of system usage data. Further investigation on the significance of (dis)continuous usage data can be carried out by small studies of iterative participatory research.

Besides the promising results of the investigated intervention, several limitations need to be considered when interpreting its findings. First, sample size was low and the one-arm study design lacks a control condition. Thus, findings of our study have to be interpreted with limited generalisation and the true magnitude of observed effects remains unclear. Also, the study design does not allow inferring the actual extent to which specific intervention elements (eg, computer and multimedia elements) effectively contributed to the observed effects. Second, participating therapists (IF and VS) lacked prior experience with the blended format, but underwent preparatory training. Careful preparation and implementation as well as regular supervision seem to be critical success factors for blended interventions,72 and as some studies on online interventions show, more experience with a given treatment can result in better outcomes.73 Third, even though clinical interviews were conducted to assess participants’ psychopathological status, other properties of our sample restrict generalisability. The majority of our sample was woman and relatively well educated. While comparable sample properties can be found in many online studies and our recruitment was based on a multimodal recruitment strategy,74 future research has to determine, if the investigated intervention proves feasible for less educated or older patients. Fourth, compared with University of Salzburg (where the intervention was developed), the institute for applied psychology lacks a fully equipped routine outpatient clinic. As a consequence, further research in routine care is needed. Fifth, half of our participants lacked alternative experience with other forms of (group) therapy. Those patients’ appraisals should be interpreted as positive experience with the undergone treatment, in the absence of experience with possible alternatives. Additionally, the group format and the use of new media might have discouraged certain patients from participating in our study.

Conclusions

The present study indicates that the blended group format is feasible for the reduction of depressive symptoms in major depression. Due to their properties, psychoeducational groups with elements of self-management or behavioural activation might be particularly suitable for blending. New media can be used for in- session and intersession support and from patients’ perspective, treatment intensification is described as an important advantage. Future research should investigate the feasibility and benefits of blended group interventions in routine care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RS: design, acquisition, analysis, drafting and revising. VMS: acquisition and analysis. IF: acquisition and analysis. TB: drafting and revising. A-RL: design, drafting and revising.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical Review Board, University of Vienna, Ref-Nr:00194.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.3rp58

References

- 1.Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:171–8. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlinson M, Rudan I, Saxena S, et al. . Setting priorities for global mental health research. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:438–46. 10.2471/BLT.08.054353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wykes T, Haro JM, Belli SR, et al. . Mental health research priorities for Europe. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:1036–42. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00332-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuijpers P, Riper H, Andersson G. Internet-based treatment of depression. Curr Opin Psychol 2015;4:131–5. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Păsărelu CR, Andersson G, Bergman Nordgren L, et al. . Internet-delivered transdiagnostic and tailored cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cogn Behav Ther 2017;46:1–28. 10.1080/16506073.2016.1231219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson G, Titov N. Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2014;13:4–11. 10.1002/wps.20083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmelkamp PM, David D, Beckers T, et al. . Advancing psychotherapy and evidence-based psychological interventions. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2014;23(Suppl 1):58–91. 10.1002/mpr.1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titov N, Dear BF, Staples LG, et al. . Mindspot clinic: an accessible, efficient, and effective online treatment service for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr Serv 2015;66:1043–50. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Kaldo V, et al. . Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in routine psychiatric care. J Affect Disord 2014;155:49–58. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenter R, Warmerdam L, Brouwer-Dudokdewit C, et al. . Guided online treatment in routine mental health care: an observational study on uptake, drop-out and effects. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:43 10.1186/1471-244X-13-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebert DD, Hannig W, Tarnowski T, et al. . [Web-based rehabilitation aftercare following inpatient psychosomatic treatment]. Rehabilitation 2013;52:164–72. 10.1055/s-0033-1345191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erbe D, Eichert HC, Riper H, et al. . Blending face-to-face and internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental disorders in adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e306 10.2196/jmir.6588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Vaart R, Witting M, Riper H, et al. . Blending online therapy into regular face-to-face therapy for depression: content, ratio and preconditions according to patients and therapists using a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:355 10.1186/s12888-014-0355-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kooistra LC, Wiersma JE, Ruwaard J, et al. . Blended vs. face-to-face cognitive behavioural treatment for major depression in specialized mental health care: study protocol of a randomized controlled cost-effectiveness trial. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:290 10.1186/s12888-014-0290-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser T, Laireiter AR. DynAMo: a modular platform for monitoring process, outcome, and algorithm-based treatment planning in psychotherapy. JMIR Med Inform 2017;5:e20 10.2196/medinform.6808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Månsson KN, Skagius Ruiz E, Gervind E, et al. . Development and initial evaluation of an Internet-based support system for face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy: a proof of concept study. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e280 10.2196/jmir.3031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ly KH, Trüschel A, Jarl L, et al. . Behavioural activation versus mindfulness-based guided self-help treatment administered through a smartphone application: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003440 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. . An investigation of computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy in the treatment of depression. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 1982;14:181–5. 10.3758/BF03202150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selmi PM, Klein MH, Greist JH, et al. . Computer-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:51–6. 10.1176/ajp.147.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman MG, Kenardy J, Herman S, et al. . The use of hand-held computers as an adjunct to cognitive-behavior therapy. Comput Human Behav 1996;12:135–43. 10.1016/0747-5632(95)00024-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JH, Wright AS, Salmon P, et al. . Development and initial testing of a multimedia program for computer-assisted cognitive therapy. Am J Psychother 2002;56:76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright JH, Wright AS, Albano AM, et al. . Computer-assisted cognitive therapy for depression: maintaining efficacy while reducing therapist time. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1158–64. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleiboer A, Smit J, Bosmans J, et al. . European COMPARative Effectiveness research on blended Depression treatment versus treatment-as-usual (E-COMPARED): study protocol for a randomized controlled, non-inferiority trial in eight European countries. Trials 2016;17:387 10.1186/s13063-016-1511-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waller G. Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behav Res Ther 2009;47:119–27. 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruwaard J, Kok R. Wild West eHealth: Time to hold our horses. European Health Psychologist 2015;17:45–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuster R, Berger T, Laireiter A-R. Computer und Psychotherapie – geht das zusammen? Zum Stand der Entwicklung von Online-und gemischten Interventionen in der Psychotherapie. Psychotherapeut 2017. 10.1007/s00278-017-0214-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riedel M. Modelle der Psychotherapieversorgung in Österreich; Endbericht; Studie im Auftrag des Hauptverbandes der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger. 2015. http://www.hauptverband.at/cdscontent/load?contentid=10008.619271&version=1430822267 (accessed 3 Apr 2015).

- 28.Weber R, Strauss B. Group psychotherapy in Germany. Int J Group Psychother 2015;65:513–25. 10.1521/ijgp.2015.65.4.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yalom ID, Leszcz M. Theory and practice of group psychotherapy. 5th edn New York: Basic books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. Clinical Guideline 90. 2009. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg123 [PubMed]

- 31.Gruber K, Moran PJ, Roth WT, et al. . Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav Ther 2001;32:155–65. 10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80050-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Przeworski A, Newman MG. Palmtop computer-assisted group therapy for social phobia. J Clin Psychol 2004;60:179–88. 10.1002/jclp.10246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman MG, Przeworski A, Consoli AJ, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of ecological momentary intervention plus brief group therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy 2014;51:198–206. 10.1037/a0032519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miloff A, Marklund A, Carlbring P. The challenger app for social anxiety disorder: New advances in mobile psychological treatment. Internet Interv 2015;2:382–91. 10.1016/j.invent.2015.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuster R, Leitner I, Carlbring P, et al. . Exploring blended group interventions for depression: Randomised controlled feasibility study of a blended computer- and multimedia-supported psychoeducational group intervention for adults with depressive symptoms. Internet Interv 2017;8:63–71. 10.1016/j.invent.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis LA, Collin P, Hurley PJ, et al. . Young men’s attitudes and behaviour in relation to mental health and technology: implications for the development of online mental health services. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:119 10.1186/1471-244X-13-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grawe K. Psychological therapy. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rehm LP. Self-management therapy for depression. Behav Res Ther 1984;6:83–98. 10.1016/0146-6402(84)90004-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ly KH, Topooco N, Cederlund H, et al. . Smartphone-Supported versus Full Behavioural Activation for Depression: A Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126559 10.1371/journal.pone.0126559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kooistra LC, Ruwaard J, Wiersma JE, et al. . Development and initial evaluation of blended cognitive behavioural treatment for major depression in routine specialized mental health care. Internet Interv 2016;4:61–71. 10.1016/j.invent.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delgadillo J, Kellett S, Ali S, et al. . A multi-service practice research network study of large group psychoeducational cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav Res Ther 2016;87:155–61. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Margraf J. Mini-DIPS: diagnostisches kurz-interview bei psychischen störungen. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margraf J, Schneider S, Ehlers A, et al. . DIPS diagnostisches interview bei psychischen störungen: interviewleitfaden. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLucia-Waack JL, Kalodner CR, Riva M. Handbook of group counseling and psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Allgemeine Depressions Skala (ADS). Manual. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Hofmeister D, et al. . Allgemeine depressions skala. manual. 2nd edn Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg DP, Williams PA. A users’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al. . The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 1997;27:191–7. 10.1017/S0033291796004242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmitz N, Kruse J, Tress W. Psychometric properties of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) in a German primary care sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999;100:462–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cano A, Sprafkin RP, Scaturo DJ, et al. . Mental health screening in primary care: a comparison of 3 brief measures of psychological distress. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001;3:206–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jack M. Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Ressourcen und Selbstmanagementfahigkeiten (FERUS). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;84:822–48. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michalak J, Heidenreich T, Ströhle G, et al. . Die deutsche Version der Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) Psychometrische Befunde zu einem Achtsamkeitsfragebogen. Z Klin Psychol Psychother 2008;37:200–8. 10.1026/1616-3443.37.3.200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brooke J. et al. . SUS: “A quick and dirty” usability scale : Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland IL, Usability evaluation in industry. London, UK: Taylor, 1996:189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bangor A, Kortum P, Miller J. Determining what individual SUS scores mean: Adding an adjective rating scale. J Usability Stud 2009;4:114–23. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt J, Lamprecht F, Wittmann WW. Zufriedenheit mit der stationären Versorgung. Entwicklung eines Fragebogens und erste Validitätsuntersuchungen. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie 1989;39:248–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. . Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979;2:197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ibm C. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM, Corp, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:12–19. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lambert MJ, Ogles BM. Using clinical significance in psychotherapy outcome research: the need for a common procedure and validity data. Psychother Res 2009;19:493–501. 10.1080/10503300902849483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. . G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zumbach J. Lernen mit neuen medien. Instruktions psychologische grundlagen. Stuttgart, Germany: Kohlhammer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bauer S, Wolf M, Haug S, et al. . The effectiveness of internet chat groups in relapse prevention after inpatient psychotherapy. Psychother Res 2011;21:219–26. 10.1080/10503307.2010.547530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schulz A, Stolz T, Vincent A, et al. . A sorrow shared is a sorrow halved? A three-arm randomized controlled trial comparing internet-based clinician-guided individual versus group treatment for social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther 2016;84:14–26. 10.1016/j.brat.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schuster R. Patients’ experiences of blended Group Therapy for Depression – Part 1: Fit and Implications for the Group Setting. 2017. osf.io/su6xt

- 67.Zwerenz R, Becker J, Knickenberg RJ, et al. . Online self-help as an add-on to inpatient psychotherapy: efficacy of a new blended treatment approach. Psychother Psychosom 2017;86:341–50. 10.1159/000481177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berger T, Krieger T, Sude K, et al. . Evaluating an e-mental health program ("deprexis") as adjunctive treatment tool in psychotherapy for depression: Results of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2018;227 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Topooco N, Riper H, Araya R, et al. . Attitudes towards digital treatment for depression: a European stakeholder survey. Internet Interv 2017;8:1–9. 10.1016/j.invent.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nicholas J, Boydell K, Christensen H. mHealth in psychiatry: time for methodological change. Evid Based Ment Health 2016;19:33–4. 10.1136/eb-2015-102278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yardley L, Spring BJ, Riper H, et al. . Understanding and promoting effective engagement with digital behavior change interventions. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:833–42. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kenter RMF, van de Ven PM, Cuijpers P, et al. . Costs and effects of internet cognitive behavioral treatment blended with face-to-face treatment: results from a naturalistic study. Internet Interv 2015;2:77–83. 10.1016/j.invent.2015.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.El Alaoui S, Hedman E, Kaldo V, et al. . Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive-behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder in clinical psychiatry. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015;83:902–14. 10.1037/a0039198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lindner P, Nyström MBT, Hassmén P, et al. . Who seeks ICBT for depression and how do they get there? Effects of recruitment source on patient demographics and clinical characteristics. Internet Interv 2015;2:221–5. 10.1016/j.invent.2015.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.