Abstract

Objectives

Explore associations between maternal and neonatal outcomes and maternal age, with particular reference to adolescent women.

Design

Population-based cohort study.

Setting

Maternity department of a large hospital in Northern England.

Participants

Primiparous women delivering a singleton at Bradford Royal Infirmary between March 2007 and December 2010 aged ≤19 years (n=640) or 20–34 years (n=3951). Subgroup analysis was performed using women aged ≤16 years (n=68). Women aged 20–34 years were used as the reference group.

Primary outcome measures

Maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Results

The odds of extremely low birth weight (<1000 g) were significantly higher in the adolescent group (≤19 years) compared with the reference group (adjusted OR (aOR) 4.13, 95% CI 1.41 to 12.11). The odds of very (<32 weeks) and extremely (<28 weeks) preterm delivery were also higher in the adolescent group (aOR 2.12, 95% CI 1.06 to 4.25 and aOR 5.06, 95% CI 1.23 to 20.78, respectively).

Women in the adolescent group had lower odds of gestational diabetes (aOR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.62), caesarean delivery (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.67 and instrumental delivery (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.67).

Conclusions

This study identifies important differences in maternal and neonatal outcomes between women by age group. These findings could help in identifying at-risk groups for additional support and tailored interventions to minimise the risk of adverse outcomes for these vulnerable groups. Further work is needed to identify the causal mechanisms linking age with outcomes in adolescent women where significant gaps in the literature exist.

Keywords: adolescents, adults, women, pregnancy, outcomes, born in Bradford

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A particular strength of this work is that it uses well-established, ethnically diverse, UK-based cohort data in a way that is unique to this study.

A further strength is in the large number of participants available for analysis that enables robust conclusions to be drawn.

Despite the large number of participants, however, this study is limited by small numbers of occurrences of some rare outcomes, particularly in subgroup analyses.

It should also be considered that the generalisability of this study to contexts that are very different in terms of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics is limited.

Introduction

Pregnancy during adolescence is often associated with less favourable outcomes for both mother and child. Childbearing in adolescence is associated with social problems such as isolation, poverty, low levels of education and unemployment.1

The impact of maternal age on obstetric and neonatal outcomes has been studied in various parts of the world and with variable results. A WHO multicountry study including 29 low-income and middle-income countries2 found adolescent mothers were at higher risk of several adverse outcomes including low birth weight, preterm delivery eclampsia and infections compared with mothers aged 20–24 years.

Similarly in higher income countries, there is evidence to suggest that health outcomes may be less favourable for younger mothers. Babies born to adolescent mothers have been shown to be at higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight,3 4 and higher rates of stillbirth and neonatal mortality have also been reported.5 Adolescents have, however, been consistently shown to experience lower rates of caesarean and instrumental delivery6 and therefore are at lower risk of complications associated with assisted births. It is not currently clear from the available literature, however, to what extent differences in birth outcomes between adolescent and adult mothers are predicted by age alone.

A systematic review7 aiming to assess the relationship between early first childbirth and increased risk of poor pregnancy outcomes found that there was considerable evidence to suggest that very young maternal age (<15 years or less than 2 years after menarche) had a negative effect on both maternal and fetal growth and infant survival. It is suggested that young women who are still themselves growing may compete with the fetus for nutrients, which may in turn impair fetal growth and result in low birthweight babies or babies who are small for their gestational age. The review also found a moderately increased risk of anaemia, premature birth and neonatal mortality associated with young maternal age. Advanced maternal age (35+ years) has also previously been shown to be an independent risk factor for adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.8 This suggests that women aged 20–34 years could reasonably be considered as the population less likely to suffer age-related pregnancy complications.

Differences in outcomes have also been associated with demographic and behavioural characteristics. Lifestyle and sociodemographic factors such as smoking,9 alcohol use10 and deprivation11 have all been shown to contribute to less favourable birth outcomes. It is also established that adolescent mothers in high-income countries are at higher risk of exhibiting these characteristics.12

The Born in Bradford study is a cohort of approximately 13 500 children born at Bradford Royal Infirmary between March 2007 and December 2010. The cohort reflects the diversity of the population in Bradford and as such is a largely biethnic sample with high levels of socioeconomic deprivation, which presents a unique opportunity to explore any differences in birth outcomes between adolescent and adult women and the factors that contribute to these differences. A detailed profile of the cohort has been previously published.13

Some work has already been carried out looking at maternal and neonatal outcomes in the Born in Bradford cohort, particularly with reference to maternal ethnicity14 15; however, this cohort has not previously been examined with reference to maternal age.

While these studies have shown some interesting associations between maternal and neonatal outcomes and maternal ethnicity, the impact of maternal age on outcomes is yet to be explored in this cohort. The size and diversity of this cohort allow for detailed analysis to be carried out and factors known to impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes to be controlled for, making this study unique in a UK context. For these reasons, the primary aim of this investigation is to explore the relationship between maternal and neonatal outcomes and maternal age in the Born in Bradford cohort.

Methods

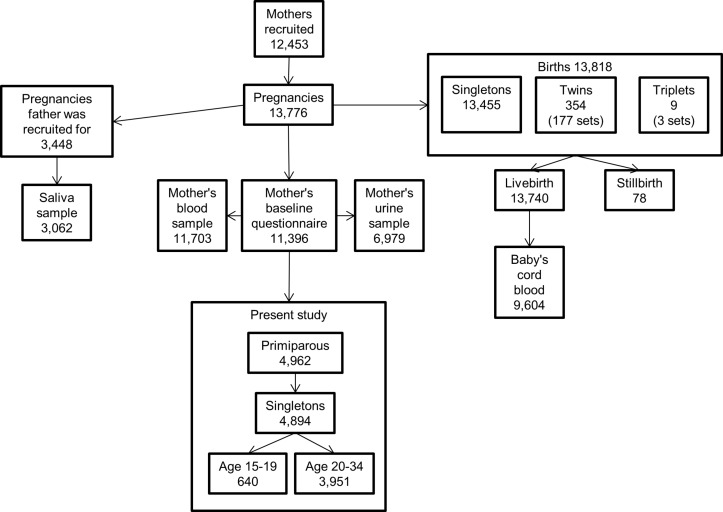

Born in Bradford is a prospective cohort study for which participants were recruited during pregnancy. The cohort was originally established in response to concerns regarding the high rates of morbidity and mortality in the city. All women booked for delivery at Bradford Royal Infirmary are offered an oral glucose tolerance test at 26–28 weeks’ gestation. Women were invited to participate in the Born in Bradford study when attending this appointment or when attending other antenatal appointments. Informed consent was obtained, and women were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire providing data on maternal characteristics. Blood and urine samples were also collected from the mothers as well as cord blood samples collected at birth. Recruitment took place between March 2007 and December 2010, and over 80% of women eligible in this period agreed to take part, which represents approximately 64% of the births occurring in Bradford during this period.13 This study uses baseline questionnaire data and hospital maternity data collected by Born in Bradford to examine maternal and neonatal outcomes. The youngest women recruited to the cohort were 15 years old; therefore, data for this study were limited to primiparous women aged 15–34 years at delivery who had a singleton pregnancy; data relating to 4591 pregnancies were available for this analysis. A flow chart describing the Born in Bradford cohort and the subset used for this study is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Details of the Born in Bradford cohort and subset used for the present study. This shows participants recruited to the main Born in Bradford cohort study and the subset of these participants whose data is used in the present study.

Outcome variables

The binary neonatal outcome variables studied were low birth weight (below 2500 g), very low birth weight (below 1500 g), extremely low birth weight (below 1000 g), macrosomia (birth weight over 4000 g), small for gestational age (birth weight lower than the 10th percentile for the sample),16 large for gestational age (birth weight higher than the 90th percentile for the sample),16 preterm birth (<37 completed weeks gestation), very preterm birth (<32 completed weeks’ gestation), extremely preterm birth (<28 completed weeks’ gestation), outcome of birth (live birth or stillbirth) and Apgar score at 1 min and 5 min (analysed as two groups: <7 and 7–10). Low, very low and extremely low birthweight and macrosomic infants were compared with infants born weighing 2500–4000 g, small and large for gestational age infants were compared with appropriate for gestational age infants and those born preterm or very or extremely preterm to those born ≥37 completed weeks’ gestation. Birth weight and gestational age at delivery were also considered as continuous variables. The maternal outcome variables included in this analysis were diagnosis of pre-eclampsia (diagnosis in this cohort was made when proteinuria is >0.3 mg and blood pressure is ≥140/90mmHg on more than one occasion), diagnosis of gestational diabetes (defined as a 2-hour postglucose load plasma glucose level of 7.8 mmol/L or a fasting plasma glucose level of 6.1 mmol/L)14 and mode of birth (normal vaginal, instrumental (including both forceps and ventouse deliveries) or caesarean section). Distinction between elective and emergency caesarean sections was not available. The outcome variables were collected in the process of routine maternity care and were made available for this analysis via data linkage to questionnaire data.

Statistical analysis

Outcomes in women aged ≤19 years were compared with outcomes for women in the reference group (20–34 years). Age group of 20–34 years was selected as the reference group as this group is the least likely to suffer age-related complications as discussed in the introduction.

Characteristics of the sample were described, presenting categorical variables as percentages and continuous variables as means and SD. This analysis was carried out both for demographic characteristics and for maternal and neonatal outcome variables. Differences between maternal age groups were explored using χ2 for categorical data and Student’s t-test for continuous data.

Simple linear regression was calculated to predict both birth weight and gestation to last completed week at delivery based on maternal age at delivery.

Logistic regression analyses were used to compare the rate of each of the binary outcome variables for adolescents and the reference group and differences between groups estimated using ORs.

Multivariate logistic regression models were then used to adjust these comparisons for confounding variables. Crude and adjusted ORs (OR and aOR) are therefore presented with 95% CIs. Index of multiple deprivation (IMD) score and maternal ethnicity (white British, Pakistani or any other ethnicity) were included as covariates in the adjusted analysis. IMD is the official measure of relative deprivation for small areas in England and combines information from seven domains of deprivation (income, employment, education, health, crime, housing and environment) to give a deprivation score.17

In the multivariate logistic regression model for this study, there is no clear logical or theoretical basis for assuming any variable to be prior to any other, either in terms of its relevance to the research goal of explaining phenomena or in terms of a hypothetical causal structure of the data. For this reason, a simultaneous model of including independent variables in the multivariate logistic regression model was considered to be most appropriate.

Further subgroup analysis was also undertaken to examine the maternal and neonatal outcomes for young women aged ≤16 years compared with the reference group and reported in the same way as the main analysis. Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS V.24.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Data were available for 4591 pregnancies for this analysis; characteristics of the participants included in the study are shown in table 1. The majority of participants in the cohort were aged 20–34 years (86.1%) with 13.9% aged 19 years or under. The sample overall was made up of 37.7% Pakistani women, 44.4% white British woman and 17.6% women of other ethnicities. Among women aged 19 years and under only 16.7% were of Pakistani ethnicity and 70% were white British. Women in the adolescent group were also more likely to have been born in the UK or Ireland (88.1%) compared with the reference group (65.5%). There were other significant variations in the characteristics of the sample by maternal age. Women in the adolescent age group were more likely to not be married or living with a partner, to be expecting their first child and to have completed lower levels of education compared with older women. Women in the adolescent age groups were also more likely to have smoked or used recreational drugs during pregnancy; they were also more likely to have drunk alcohol in the first trimester. Women in the reference group were more likely to be overweight or obese, while adolescent women were found to have higher prevalence of underweight. Older women were also more likely to have taken nutritional supplements in the 4 weeks before questionnaire completion compared with younger women. Analysis of continuous variables showed that IMD score decreased as maternal age increased suggesting adolescent women lived in areas of higher deprivation. Adolescent women also booked with a midwife for antenatal care later than older women; there was a mean difference of 1 week between the two groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample by maternal age

| ≤19 | 20–34 | Total | Missing | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | P values | |

| Whole cohort | 640 | 13.9 | 3951 | 86.1 | 4591 | 100 | |||

| Ethnicity | 14 | 0.3 | |||||||

| Pakistani | 107 | 16.7 | 1623 | 41.1 | 1730 | 37.7 | <0.001 | ||

| White British | 448 | 70.0 | 1590 | 40.2 | 2038 | 44.4 | |||

| Any other ethnicity | 85 | 13.3 | 724 | 18.3 | 809 | 17.6 | |||

| Mother’s country of birth | 1 | 0.0 | |||||||

| UK and Ireland | 564 | 88.1 | 2588 | 65.5 | 3152 | 68.7 | <0.001 | ||

| Southeast Asia | 41 | 6.4 | 984 | 24.9 | 1025 | 22.3 | |||

| Eastern Europe | 15 | 2.3 | 135 | 3.4 | 150 | 3.3 | |||

| Other/unknown | 20 | 3.1 | 243 | 6.2 | 263 | 5.7 | |||

| Marital status | 9 | 0.2 | |||||||

| Married | 87 | 13.6 | 2445 | 61.9 | 2532 | 55.2 | <0.001 | ||

| Not married – living with partner | 147 | 23.0 | 841 | 21.3 | 988 | 21.5 | |||

| Single | 406 | 63.4 | 656 | 16.6 | 1062 | 23.1 | |||

| Parents related other than by marriage | 3 | 0.1 | |||||||

| Yes | 76 | 11.9 | 988 | 25.0 | 1064 | 23.2 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 564 | 88.1 | 2960 | 74.9 | 3524 | 76.8 | |||

| Highest level of education | 14 | 0.3 | |||||||

| Less than 5 GCSEs grades A–C or equivalent | 231 | 36.1 | 553 | 14.0 | 784 | 17.1 | <0.001 | ||

| 5 GCSEs grades A–C or equivalent | 298 | 46.6 | 1121 | 28.4 | 1419 | 30.9 | |||

| A-levels or higher | 60 | 9.4 | 1971 | 49.9 | 2031 | 44.2 | |||

| Other/unknown | 50 | 7.8 | 293 | 7.4 | 343 | 7.5 | |||

| Smoked during pregnancy | 7 | 0.2 | |||||||

| Yes | 302 | 47.2 | 608 | 15.4 | 910 | 19.8 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 338 | 52.8 | 3336 | 84.4 | 3674 | 80.0 | |||

| Drunk alcohol in the first 3 months of pregnancy | 2862 | 62.3 | |||||||

| Yes | 185 | 28.9 | 698 | 17.7 | 883 | 19.2 | 0.068 | ||

| No | 140 | 21.9 | 702 | 17.8 | 842 | 18.3 | |||

| Don’t know | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.1 | |||

| Drunk alcohol since the fourth month of pregnancy | 2872 | 62.6 | |||||||

| Yes | 89 | 13.9 | 478 | 12.1 | 567 | 12.4 | 0.06 | ||

| No | 233 | 36.4 | 916 | 23.2 | 1149 | 25.0 | |||

| Don’t know | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.1 | |||

| Used recreational drugs during pregnancy | 771 | 16.8 | |||||||

| Yes | 29 | 4.5 | 47 | 1.2 | 76 | 1.7 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 509 | 79.5 | 3235 | 81.9 | 3744 | 81.6 | |||

| Used any vitamins or iron supplements in the last 4 weeks | 16 | 0.3 | |||||||

| Yes | 152 | 23.8 | 1610 | 40.7 | 1762 | 38.4 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 487 | 76.1 | 2326 | 58.9 | 2813 | 61.3 | |||

| BMI category | 413 | 9 | |||||||

| Underweight (below 18.5) | 59 | 9.2 | 199 | 5.0 | 258 | 5.6 | <0.001 | ||

| Healthy weight (18.5–24.9) | 368 | 57.5 | 1853 | 46.9 | 2221 | 48.4 | |||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 113 | 17.7 | 955 | 24.2 | 1068 | 23.3 | |||

| Obese (30 or higher) | 46 | 7.2 | 585 | 14.8 | 631 | 13.7 | |||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | % | P values | |

| BMI at booking appointment | 594 | 23.3 (4.6) | 3641 | 25.1 (5.4) | 4235 | 24.8 (5.3) | 356 | 7.8 | <0.001 |

| IMD score | 640 | 44.7 (18.0) | 3948 | 41.6 (17.9) | 4588 | 41.8 (17.9) | 3 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Number of weeks’ gestation at booking appointment | 640 | 12.1 (5.0) | 3951 | 11.4 (4.3) | 4246 | 12.4 (3.1) | 345 | 7.5 | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index (kg/m²); GCSE, General certificate of secondary education; IMD, Index of multiple deprivation.

Descriptive analysis relating to maternal and neonatal outcomes is shown in table 2. This analysis suggests that there are several outcome variables that show significant variation by maternal age group. Among the neonatal outcomes, the results show babies born to adolescent women were significantly more likely to have extremely low birth weights or to be born very or extremely preterm. Among the maternal outcomes, lower rates of gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery and instrumental birth were associated with adolescent age.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of maternal and neonatal outcomes by maternal age

| ≤19 | 20–34 | Total | Missing | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | P values | |

| Whole cohort | 640 | 13.9 | 3951 | 86.1 | 4591 | 100 | |||

| Neonatal outcomes | |||||||||

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 56 | 9.3 | 349 | 9.4 | 405 | 9.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.933 |

| Very low birth weight (<1500 g) | 9 | 1.6 | 36 | 1.1 | 45 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.248 |

| Extremely low birth weight (<1000 g) | 6 | 1.1 | 10 | 0.3 | 16 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.007 |

| Macrosomia (birth weight >4000 g) | 35 | 6.0 | 223 | 6.2 | 258 | 6.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.852 |

| Small for gestational age | 81 | 14.0 | 576 | 16.3 | 657 | 16.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.153 |

| Large for gestational age | 61 | 10.9 | 426 | 12.6 | 487 | 12.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.256 |

| Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) | 44 | 6.9 | 236 | 6.0 | 280 | 6.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.376 |

| Very preterm delivery (<32 weeks) | 12 | 2.0 | 35 | 0.9 | 47 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.021 |

| Extremely preterm delivery (<28 weeks) | 4 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.008 |

| Stillborn | 5 | 0.8 | 26 | 0.7 | 31 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.724 |

| Apgar score <7 at 1 min | 75 | 11.7 | 456 | 11.5 | 531 | 11.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.896 |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 min | 24 | 3.8 | 136 | 3.4 | 160 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.694 |

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | % | P values | |

| Birth weight (g) | 640 | 3167.6 (580.6) | 3950 | 3183.1 (556.3) | 4590 | 3180.9 (559.7) | 1 | 0.0 | 0.919 |

| Gestation to last completed week | 640 | 39.2 (2.2) | 3951 | 39.2 (1.9) | 4591 | 39.2 (1.9) | 0 | 0.0 | 0.516 |

| Maternal outcomes | |||||||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 19 | 3.0 | 146 | 3.7 | 165 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.36 |

| Gestational diabetes | 13 | 2.0 | 264 | 6.7 | 277 | 6.0 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Caesarean delivery | 93 | 14.5 | 990 | 25.1 | 1083 | 23.6 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| Instrumental birth* | 78 | 14.3 | 706 | 23.9 | 784 | 22.4 | 5 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

*Vaginal deliveries only, included both forceps and ventouse deliveries.

Linear regression models

A simple linear regression was carried out to assess the relationship between birth weight and maternal age. A statistically significant relationship was found (P=0.044). The slope coefficient for maternal age was 3.749, meaning that for each 1-year increase in maternal age, birth weight increases by 3.749 g. The R2 value was 0.001, meaning that only 0.1% of the variation in birth weight can be explained by the model containing only maternal age.

Similarly, a simple linear regression to assess the relationship between gestation at delivery to last completed week and maternal age found a significant relationship (P=0.011). The slope coefficient for maternal age was −0.016, meaning that for each 1-year increase in maternal age gestation at delivery decreases by 0.016 weeks. The R2 value for this regression was also 0.001, meaning that only 0.1% of the variation in gestation at delivery can be explained by the model containing only maternal age.

Logistic regression analysis

The crude and aORs for maternal and neonatal outcomes by maternal age group are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Neonatal and maternal outcomes for adolescent women

| n | Crude OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)* | |

| Neonatal outcomes | |||

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 4332 | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.33) | 1.10 (0.81 to 1.50) |

| Very low birth weight (<1500 g) | 3972 | 1.54 (0.74 to 3.21) | 1.59 (0.74 to 3.42) |

| Extremely low birth weight (<1000 g) | 3943 | 3.69 (1.34 to 10.20) | 4.13 (1.41 to 12.11) |

| Macrosomia (birth weight >4000 g) | 4185 | 0.97 (0.67 to 1.40) | 0.78 (0.54 to 1.14) |

| Small for gestational age | 4104 | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.07) | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.37) |

| Large for gestational age | 3934 | 0.85 (0.64 to 1.13) | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.99) |

| Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) | 4591 | 1.16 (0.83 to 1.62) | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.56) |

| Very preterm delivery (<32 weeks) | 4358 | 2.14 (1.10 to 4.14) | 2.12 (1.06 to 4.25) |

| Extremely preterm delivery (<28 weeks) | 4320 | 4.99 (1.34 to 18.62) | 5.06 (1.23 to 20.78) |

| Stillborn | 4591 | 1.19 (0.46 to 3.11) | 1.39 (0.51 to 3.80) |

| Apgar score <7 at 1 min | 4591 | 1.02 (0.79 to 1.32) | 0.95 (0.73 to 1.25) |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 min | 4591 | 1.09 (0.70 to 1.70) | 1.11 (0.70 to 1.76) |

| Maternal outcomes | |||

| Pre-eclampsia | 4591 | 0.80 (0.49 to 1.30) | 0.84 (0.51 to 1.39) |

| Gestational diabetes | 4591 | 0.29 (0.17 to 0.51) | 0.35 (0.20 to 0.62) |

| Caesarean delivery | 4591 | 0.51 (0.40 to 0.64) | 0.53 (0.42 to 0.67) |

| Instrumental birth† | 3503 | 0.53 (0.41 to 0.69) | 0.53 (0.41 to 0.69) |

Reference group: maternal age 20–34 years.

*Adjusted for IMD score and ethnicity.

†Vaginal deliveries only, included both forceps and ventouse deliveries.

aOR, adjusted OR; IMD, Index of multiple deprivation.

Women in the adolescent age group were found to have a significantly higher odds of delivering extremely low birthweight babies (<1000 g) compared with the reference group (aOR 4.13, 95% CI 1.41 to 12.11) and delivering extremely preterm (<28 weeks) (aOR 5.06, 95% CI 1.23 to 20.78). Adolescent pregnant women experienced lower odds of being diagnosed with gestational diabetes than the reference group (aOR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.62). The odds of women in this age group delivering by caesarean section were decreased (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.67), as were the odds of having an instrumental delivery (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.69) compared with the reference group.

Subgroup analysis

For some outcomes, the number of events occurring in the subgroup aged ≤16 years, was either very small or no events took place. This resulted in either the regression model failing to produce a valid result or the aOR being subject to extremely wide CIs. The results presented do however provide a useful indication of the outcomes that may be important for further investigation. Results of the subgroup analysis are shown in table 4. The only variable to return a significant result in this analysis was for incidence of caesarean section where the odds were lower for women in the ≤16 subgroup (aOR 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.72).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of neonatal and maternal outcomes

| n ≤16 | n 20–34 | Total valid n | Crude OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI)* | |

| 68 | 3951 | ||||

| Neonatal outcomes | |||||

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 5 | 349 | 3792 | 0.81 (0.32 to 2.02) | 0.83 (0.32 to 2.13) |

| Very low birth weight (<1500 g) | 2 | 36 | 3476 | 3.13 (0.74 to 13.29) | 3.00 (0.66 to 13.59) |

| Extremely low birth weight (<1000 g) | 1 | 10 | 3449 | 5.63 (0.71 to 44.68) | 5.90 (0.67 to 51.85) |

| Macrosomia (birth weight >4000 g) | 3 | 223 | 3664 | 0.76 (0.24 to 2.43) | 0.62 (0.19 to 2.02) |

| Small for gestational age | 6 | 576 | 3585 | 0.57 (0.24 to 1.33) | 0.74 (0.31 to 1.77) |

| Large for gestational age | 8 | 426 | 3437 | 1.03 (0.49 to 2.17) | 0.91 (0.42 to 1.95) |

| Preterm delivery (<37 weeks) | 5 | 236 | 4019 | 1.25 (0.50 to 3.14) | 1.08 (0.42 to 2.76) |

| Very preterm delivery (<32 weeks) | 1 | 35 | 3814 | 1.69 (0.23 to 12.49) | 1.66 (0.21 to 12.88) |

| Extremely preterm delivery (<28 weeks) | 1 | 5 | 3784 | 11.79 (1.36 to 102.41) | 6.24 (0.61 to 64.20) |

| Stillborn | 0 | 26 | 4019 | † | † |

| Apgar score <7 at 1 min | 9 | 456 | 4019 | 1.17 (0.58 to 2.37) | 1.02 (0.50 to 2.11) |

| Apgar score <7 at 5 min | 2 | 136 | 4019 | 0.85 (0.21 to 3.51) | 0.85 (0.20 to 3.60) |

| Maternal outcomes | |||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 4 | 146 | 4019 | 1.63 (0.59 to 4.53) | 1.71 (0.59 to 4.91) |

| Gestational diabetes | 0 | 264 | 4019 | † | † |

| Caesarean delivery | 6 | 990 | 4019 | 0.29 (0.13 to 0.67) | 0.31 (0.13 to 0.72) |

| Instrumental birth‡ | 14 | 706 | 3025 | 0.83 (0.46 to 1.50) | 0.87 (0.47 to 1.60) |

Reference group: maternal age 20–34 years.

*Adjusted for IMD score and ethnicity.

†No valid result available due to small numbers.

‡Vaginal deliveries only, included both forceps and ventouse deliveries.

aOR, adjusted OR; IMD, Index of multiple deprivation.

Discussion

Analysis of maternal and neonatal outcomes in the Born in Bradford cohort in this study has found some important differences between women in different age groups.

Adolescent women in the sample were found to be at significantly increased risk of delivering babies extremely preterm and with extremely low birth weights after adjustment for confounding factors. Identifying the risk of delivering babies with an extremely low birth weight is of particular importance due to its association with neonatal mortality and morbidity. Babies with extremely low birth weight are more likely to die in the first few months of life18 and are more likely to have long lasting physical and cognitive developmental issues19compared with babies born at higher weights. Extreme low birth weight and extreme preterm delivery are intrinsically linked, and thus morbidity and mortality in extremely preterm infants is similar to those with extremely low birth weights.20

Preterm deliveries may be clinically indicated due to medical factors such as intrauterine growth restriction or spontaneous. Both spontaneous preterm delivery20 and intrauterine growth restriction21 have been shown to be associated with maternal under nutrition, and the links between intrauterine growth restriction and maternal smoking during pregnancy are well established.20 22 23 This study has identified a higher prevalence of both maternal underweight and smoking during pregnancy among the adolescent group compared with controls, suggesting that these may be important mechanisms for further investigation in examining the causes of poorer outcomes in adolescent pregnancies.

In the UK, survival rates for babies born extremely preterm increase rapidly with each additional week the fetus remains in the womb from close to 0 at 22 weeks’ gestation to 92% at 28 completed weeks,24 meaning that neonatal death is a significant concern for babies born in this time period. Mortality data were not available for this study for infants who were born alive; this would be an important area for further study to assess how mortality rates in preterm infants born to adolescent mothers compare with those born to older women.

The linear regression analysis of both birth weight and gestation at delivery showed statistically significant results. This said, the R2 value for both of these analyses showed that maternal age accounted for only 0.1% of the variation in the analysis, meaning that the clinical importance of this finding is limited. It is likely that there are a number of variables that were either not measured in this study or that are currently unknown in the research literature that contribute to these outcomes.

Adolescent women were also found to be at significantly lower risk of caesarean and instrumental delivery in this analysis. Caesarean delivery is associated with higher rates of postnatal complications and increased recovery time for the mother.25 Instrumental deliveries, while necessary to prevent serious neonatal complications, are associated with a higher prevalence of birth injuries and maternal rehospitalisation.26 These results are consistent with a large body of existing work where these outcomes have been found to be associated with maternal age.27 28 It is not known whether these differences are due to biological differences between younger and older women or whether the reasons are more likely to be social or cultural. Further investigation regarding the reasons for difference in mode of birth in women of different ages would be advantageous. The results of this study are consistent with a number of previous similar studies. Results from a study looking at differences in outcomes between adolescent mothers and an older reference group from the North Western Perinatal Survey29 found an increased risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery among adolescent mothers. This study also measured the effect of parity on these outcomes and reported and increased effect in the second pregnancies of adolescents. Analysis in the present study was limited to primiparous mothers only in order to control for the impact of parity in comparison with the control group. There were insufficient numbers of multiparous women in the adolescent group to allow for analysis of these as a separate group in this study; however, the results of this previous study suggest that by excluding second and subsequent pregnancies, the extent of low birth weight and preterm delivery may have been underestimated.

A further study30 comparing adolescent pregnancy outcomes with those of older women found a decreased risk of caesarean section and instrumental delivery in the adolescent group, which is consistent with the findings of this study. This study did however fail to find any association with low birth weight or preterm delivery after adjusting for confounding variables. This analysis did not however look at extreme low birth weight or extreme preterm delivery, which is where the present study has detected differences between groups. Comparison of the results of this study to key indicators published by Public Health England’s Child and Maternal Health Intelligence Network31 suggests that despite the uniqueness of this cohort, the results are generalisable to other areas of the UK. Reported national rates for smoking in pregnancy, low birth weight and stillbirth are similar both among the adolescent population and the population as a whole to those reported in this study.

The results of this study contribute to the wider understanding of neonatal and maternal morbidity and mortality both in a UK context and internationally. This study identifies important differences in the risk of adverse outcomes by maternal age, which align with the United Nations sustainable development goals32 and the targets outlined in the Every Woman, Every Child Global Strategy.33 Preterm births and low birth weights are a major cause of neonatal death and cause more than 1 million deaths globally per year.34 In addition to this, the second leading cause of death for young women aged 15–19 years is complications during pregnancy and childbirth.35 Identifying characteristics that put individuals at higher risk of these complications will help in targeting interventions to populations that are appropriate to their setting.

A significant strength of this study is that it uses a large cohort study, meaning that the majority of statistical analyses do not suffer from problems due to small numbers and the population recruited the cohort is largely representative of the population as a whole. There are however some small difference between the populations recruited and not recruited that should be acknowledged. A lower proportion of mothers aged 20–24 years were recruited compared with those not in the cohort and a higher proportion of South Asian and primiparous women. A lower proportion of mothers at the lower end of the control group may therefore have had some bearing on the prevalence of some outcomes in that group, which is a limitation of this study.

Attempts were made to control for the effect of confounding variables in the multivariate logistic regression model by including a measure of socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity in the model and by restricting the analysis to primiparous women delivering a singleton. These variables were selected due to their independent association with the outcome variables. Other variables were not included in the model due to a high degree of correlation between variables. There still exists, however, the possibility that the effect sizes detected in this study are influenced by unmeasured or residual confounding variables.

Despite the large numbers overall, there was still only a relatively small number of adolescent women in the cohort, particularly in the subgroup analysis. Stillbirth, premature deliveries and very and extremely low birth weights were also relatively rare events, meaning that this study may have failed to detect differences in outcomes between groups due to being insufficiently powered.

The availability of routine hospital data linked to the cohort data was also a significant strength of this study. The use of this data did however also present limitations in that the analysis was restricted to the variables collected routinely, and there was no opportunity to recover missing data.

Conclusions

This study identifies some important variations in obstetric and perinatal outcomes by maternal age. Extremely low birth weight and extremely preterm delivery were concerns for adolescent mothers. Findings relating to maternal outcomes were also consistent with the existing literature showing lower risk of gestational diabetes, caesarean delivery and instrumental birth. Further work to establish the causal mechanisms behind the links between maternal age and maternal and neonatal outcomes would be advantageous, particularly for adolescent mothers where there are significant gaps in the existing literature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Born in Bradford is only possible because of the enthusiasm and commitment of the children and parents in BiB. We are grateful to all the participants, practitioners and researchers who have made Born in Bradford happen.

Footnotes

Contributors: KM-D: completion of data analysis and responsible for writing the manuscript. KK: providing specialist input on statistical methods. VJB: providing specialist input on methods and structure, providing comments and making amendments to the manuscript. HS: providing specialist input on methods and structure, providing comments and making amendments to the manuscript.

Funding: The research wasfunded by the NIHR CLAHRC Yorkshire and Humber through the White Rose PhD studentship network. The views expressedare those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR orthe Department of Health and Social Care. The Born in Bradford study presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC) and the Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0407-10044).

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was granted by Bradford Research Ethics Committee (ref no. 07/H1302/112).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Requests for access to data should be addressed to the corresponding author or to the Born in Bradford programme manager rosie.mceachan@bthft.nhs.uk.

References

- 1.Cook SMC, Cameron ST. Social issues of teenage pregnancy. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine 2015;25:243–8. 10.1016/j.ogrm.2015.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganchimeg T, Ota E, Morisaki N, et al. Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a World Health Organization multicountry study. BJOG 2014;121 Suppl 1:40–8. 10.1111/1471-0528.12630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert W, Jandial D, Field N, et al. Birth outcomes in teenage pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2004;16:265–70. 10.1080/jmf.16.5.265.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyrberg RB, Blomberg M, Kjølhede P. Deliveries among teenage women - with emphasis on incidence and mode of delivery: a Swedish national survey from 1973 to 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:1 10.1186/1471-2393-13-204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohsin M, Bauman AE, Jalaludin B. The influence of antenatal and maternal factors on stillbirths and neonatal deaths in New South Wales, Australia. J Biosoc Sci 2006;38:643–57. 10.1017/S002193200502701X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomberg M, Birch Tyrberg R, Kjølhede P. Impact of maternal age on obstetric and neonatal outcome with emphasis on primiparous adolescents and older women: A Swedish Medical Birth Register Study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005840 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs CM, Wendt A, Peters S, et al. The impact of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26 Suppl 1:259–84. 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01290.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenny LC, Lavender T, McNamee R, et al. Advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcome: evidence from a large contemporary cohort,. PLoS One 2013;8:e56583 10.1371/journal.pone.0056583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollack H, Lantz PM, Frohna JG. Maternal smoking and adverse birth outcomes among singletons and twins. Am J Public Health 2000;90:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaddoe VW, Bakker R, Hofman A, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight and preterm birth. The generation R study. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:834–40. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:263–72. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.East PL, Felice ME. Adolescent pregnancy and parenting: findings from a racially diverse sample. Psychology Press 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright J, Small N, Raynor P, et al. Cohort profile: the Born in Bradford multi-ethnic family cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:978–91. 10.1093/ije/dys112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West J, Lawlor DA, Fairley L, et al. Differences in socioeconomic position, lifestyle and health-related pregnancy characteristics between Pakistani and White British women in the Born in Bradford prospective cohort study: the influence of the woman’s, her partner’s and their parents' place of birth. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004805 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairley L, Petherick ES, Howe LD, et al. Describing differences in weight and length growth trajectories between white and Pakistani infants in the UK: analysis of the Born in Bradford birth cohort study using multilevel linear spline models. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:274–9. archdischild-2012 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardosi J, Chang A, Kalyan B, et al. Customised antenatal growth charts. The Lancet 1992;339:283–7. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91342-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Office for National Statistics, English indices of deprivation 2015.https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015(accessed 17 Nov 2017).

- 18.Saugstad OD, Aune D. Optimal oxygenation of extremely low birth weight infants: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the oxygen saturation target studies. Neonatology 2014;105:55–63. 10.1159/000356561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luttikhuizen dos Santos ES, de Kieviet JF, Königs M, et al. Predictive value of the Bayley scales of infant development on development of very preterm/very low birth weight children: a meta-analysis. Early Hum Dev 2013;89:487–96. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, et al. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. The Lancet 2008;371:75–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valsamakis G, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Malamitsi-Puchner A, et al. Causes of intrauterine growth restriction and the postnatal development of the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1092:138–47. 10.1196/annals.1365.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horta BL, Victora CG, Menezes AM, et al. Low birthweight, preterm births and intrauterine growth retardation in relation to maternal smoking. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1997;11:140–51. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1997.d01-17.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordentoft M, Lou HC, Hansen D, et al. Intrauterine growth retardation and premature delivery: the influence of maternal smoking and psychosocial factors. Am J Public Health 1996;86:347–54. 10.2105/AJPH.86.3.347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tommy’s. Premature Birth Statistics, [online]. https://www.tommys.org/our-organisation/why-we-exist/premature-birth-statistics (accessed 17 Nov 2017).

- 25.van Ham MA, van Dongen PW, Mulder J. Maternal consequences of caesarean section. A retrospective study of intra-operative and postoperative maternal complications of caesarean section during a 10-year period. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1997;74:1–6. 10.1016/S0301-2115(97)02725-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Martin DP, et al. Association between method of delivery and maternal rehospitalization. JAMA 2000;283:2411–6. 10.1001/jama.283.18.2411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jolly M, Sebire N, Harris J, et al. The risks associated with pregnancy in women aged 35 years or older. Hum Reprod 2000;15:2433–7. 10.1093/humrep/15.11.2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobsson B, Ladfors L, Milsom I. Advanced maternal age and adverse perinatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2004;104:727–33. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000140682.63746.be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freinkel N, Metzger BE, Phelps RL, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: heterogeneity of maternal age, weight, insulin secretion, HLA antigens, and islet cell antibodies and the impact of maternal metabolism on pancreatic B-cell and somatic development in the offspring. Diabetes 1985;34(Suppl 2):1–7. 10.2337/diab.34.2.S1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khashan AS, Baker PN, Kenny LC. Preterm birth and reduced birthweight in first and second teenage pregnancies: a register-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010;10:36 10.1186/1471-2393-10-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Vienne CM, Creveuil C, Dreyfus M. Does young maternal age increase the risk of adverse obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcomes: a cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2009;147:151–6. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Public Health England, Teenage Parent Outcomes Modelling Tool. http://www.chimat.org.uk/teenconceptions/chimattools(accessed 12 Dec 2016).

- 33.United Nations, Sustainable Development Goals.http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html(accessed 12 Dec 2016).

- 34.Child EW. Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health. New York, NY: Every Woman Every Child, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organisation. Adolescent pregnancy fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs364/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.