Abstract

Introduction

Many researchers have addressed overdosage and inappropriate use of antibiotics. Many meta-analyses have investigated antibiotic prophylaxis for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy with the aim of reducing unnecessary antibiotic use. Most of these meta-analyses have concluded that prophylactic antibiotics are not required for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomies. This study aimed to assess the validity of this conclusion by systematically reviewing these meta-analyses.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken. Searches were limited to meta-analyses and systematic reviews. PubMed and Cochrane Library electronic databases were searched from inception until March 2016 using the following keyword combinations: ‘antibiotic prophylaxis’, ‘laparoscopic cholecystectomy’ and ‘systematic review or meta-analysis’. Two independent reviewers selected meta-analyses or systematic reviews evaluating prophylactic antibiotics for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. All of the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) analysed in these meta-analyses were also reviewed.

Results

Seven meta-analyses regarding prophylactic antibiotics for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy that had examined a total of 28 RCTs were included. Review of these meta-analyses revealed 48 miscounts of the number of outcomes. Six RCTs were inappropriate for the meta-analyses; one targeted patients with acute cholecystitis, another measured inappropriate outcomes, the original source of a third was not found and the study protocols of the remaining three were not appropriate for the meta-analyses. After correcting the above miscounts and excluding the six inappropriate RCTs, pooled risk ratios (RRs) were recalculated. These showed that, contrary to what had previously been concluded, antibiotics significantly reduced the risk of postoperative infections. The rates of surgical site, distant and overall infections were all significantly reduced by antibiotic administration (RR (95% CI); 0.71 (0.51 to 0.99), 0.37 (0.19 to 0.73), 0.50 (0.34 to 0.75), respectively).

Conclusions

Prophylactic antibiotics reduce the incidence of postoperative infections after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: laparoscopic cholecystectomy, meta-analysis, prophylactic antibiotics, randomized controlled trial, surgical site infection, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to systematically review and reappraise previously reported meta-analyses.

Many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses concerning prophylactic antibiotic administration have been performed to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. We reassessed all of these meta-analyses and their related RCTs.

We found 48 miscounts of the number of outcomes as well as six RCTs that were inappropriate for selection in the meta-analyses.

Because the RCTs included in these meta-analyses were performed in many countries with different life environments and health care systems, drawing definitive conclusions about the effects of antibiotic prophylaxis is problematic.

Introduction

Many clinical researchers have addressed the issue of overdosage of antibiotics and inappropriate administration because antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest current threats to global health. Moreover, developed nations are facing increasing medical costs associated with the ageing of the population. Accordingly, many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) concerning prophylactic antibiotic administration for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy have been performed with the aim of reducing unnecessary antibiotic use and thus minimising antibiotic resistance and controlling increasing medical costs. Additionally, many meta-analyses1–7 have analysed a large number of RCTs8–35 to evaluate the role of prophylactic antibiotics for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy. All of these meta-analyses have found no significant difference in the rate of postoperative infectious complications, including surgical site infections (SSIs), between patients receiving versus not receiving prophylactic antibiotics. It has therefore been concluded that prophylactic antibiotics are not required for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, most trials in these meta-analyses had such small samples that they were considered statistically underpowered for the rare event of postoperative infections after low-risk cholecystectomies. Meta-analyses that reviewed small RCTs are problematic in that the true rates of postoperative infections may have been underestimated.36 In addition, the most recently published meta-analysis regarding this clinical issue37 reached a conclusion that was contrary to those of all of the previously published meta-analyses. We therefore performed a systematic review of meta-analyses on antibiotic prophylaxis for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy to reassess the results of the previously published meta-analyses that concluded no need for antibiotics and to review all of the RCTs examined by them.

Methods

To reappraise previously published meta-analyses or systematic reviews, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were searched in March 2016 using the following keyword combinations: ‘antibiotic prophylaxis’, ‘laparoscopic cholecystectomy’ and ‘systematic review or meta-analysis’. The current systematic review for meta-analyses and systematic reviews was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.38 Only meta-analyses and systematic reviews that were in English were searched. Additionally, all of the RCTs that were analysed in these meta-analyses were collected and reviewed and the outcomes described in each meta-analysis compared with those reported in their original RCTs. Two investigators extracted and reviewed the data independently. Disagreements were resolved by interaction, discussion and consensus.

For the present review, prophylactic antibiotics were defined as antibiotics that were provided preoperatively, or preoperatively and postoperatively, for preventing postoperative infectious complications. Patients at low risk of developing postoperative complications were defined as those undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases and did not include those undergoing urgent surgery. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of RCTs comparing antibiotic treatment with placebo or no treatment in patients with benign gallbladder diseases undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included. The outcomes of rates of SSI, distant infection and overall infection were assessed.

SSIs were defined as superficial or deep incisional infections or organ/space infections according to the Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection 1999.39 Distant infections were defined as infections occurring at sites other than the surgical site. Overall infections were defined as the sum of SSIs and distant infections. Some of the meta-analyses did not use the SSI classification specified in this guidelines but classified infections as ‘wound infections’ or ‘major infections’. In the present study, these infections were reclassified according to the SSI classification. Organ/space infections that had been reported as ‘major infections’ were treated as SSIs and recalculated. Similarly, distant infections that were reported as ‘major infections’ were treated as distant infections.

The following data regarding eligible meta-analyses were retrieved: eligibility criteria, information sources, search methods, study selection, data collection process, synthesis of results, number of RCTs examined, total number of patients, heterogeneity results, analysis methods used, pooled SSIs, pooled distant infections, pooled overall infections and conclusions. All of the original reports of RCTs that were analysed in each meta-analysis were then collected and the following data retrieved from then when reported: patient characteristics, study design, eligibility criteria, antibiotic treatment schedule, number of randomised patients, SSIs, distant infections and overall infections. The outcomes used in each meta-analysis were meticulously compared with those reported for their original RCTs.

Statistical analysis

Standard meta-analysis methods were applied according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions40 to evaluate the effect of antibiotics on the incidence of SSIs, distant infections and overall infections. Data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. When this information was not available, per-protocol data were used. Outcome measures were risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs weighted by the inverse of their variances. Antibiotic treatment was considered the experimental treatment; thus RRs are reported as antibiotic/no antibiotic ratios. Consistency of results (effect sizes) among studies was assessed using two standard heterogeneity tests, the χ2 test-based Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic. Inconsistency across studies was considered as low, moderate and high for I2 values below 40%, between 30% and 60% and greater than 50%, respectively, according to the Cochrane Handbook.39 Heterogeneity was considered significant when the I2 value was greater than 50%, the Cochran’ s Q test P value was less than 0.1 or both. Fixed-effects and random-effects models were used to calculate the overall effect. The fixed-effects model was calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method and the random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird method. R statistical software V.3.1.1 was used for all calculations.

Results

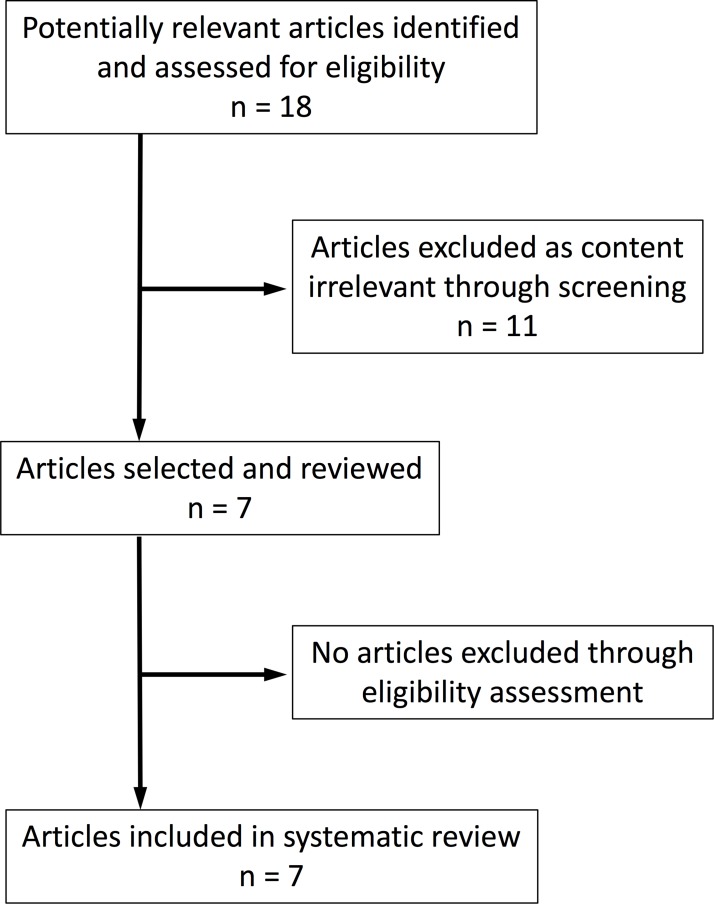

The search yielded 18 articles of which 11 were excluded for following reasons; 8 had irrelevant contents, 2 were not in English and the remaining 1 was not a meta-analysis or systematic review. Whereas there were no discrepancies between the two observers regarding decisions to include/exclude each meta-analysis, there were two discrepancies regarding decisions to include/exclude each RCT. The reasons for these discrepancies were as follows: one observer had overlooked an inappropriate study design for reference 23 and inappropriate outcome measures for reference 28. These discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two observers. Results of the full search strategy and Kappa statistics are shown in online supplementary appendices S1 and S2, respectively.

After exclusions, seven meta-analyses1–7 in English regarding prophylactic antibiotics for low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy remained (figure 1), all of which were published between January 2003 and January 2016. Table 1 shows the sample sizes, outcomes and conclusions of these meta-analyses. Two1 5 of these seven meta-analyses did not calculate overall incidence of infections. As to analysis methods, the fixed-effects model was used in two studies4 5 and the random-effects model in two studies.2 7 The remaining three studies did not mention which model was used for the final evaluation.1 3 6 No heterogeneity was found in any of the meta-analyses except for overall rate of infection in the most recent meta-analysis.7 Four1 3 4 6 of these seven meta-analyses did not use the SSI classification. As described in the Methods section, the outcomes in these studies were reclassified according to the SSI classification for the present study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of articles included in the systematic review.

Table 1.

Previous meta-analyses regarding prophylactic antibiotics for laparoscopic cholecystectomy

| Published date | Group | Analysis model | Heterogeneity | No. of postoperative infections (%) | OR (95% CI) of the overall infections | Conclusions | ||

| (No. of RCTs included) | SSIs | Distant infections | Overall infections | |||||

| 20031 (5) | Antibiotics | Not stated | Not significant | 9/528 (1.7) | 4/528 (0.8) | — | — | Do not support the use of prophylactic antibiotics |

| Control | 9/371 (2.4) | 6/371 (1.6) | — | |||||

| 20042 (6) | Antibiotics | Random effects | Not significant | 12/567 (2.1) | 4/567 (0.7) | 16/567 (2.8) | 0.69 (0.34 to 1.43) | No need to administer routine antibiotics |

| Control | 12/407 (2.9) | 6/407 (1.5) | 18/407 (4.4) | |||||

| 20083 (9) | Antibiotics | Not stated | Not significant | 15/797 (1.9) | 4/499 (0.8) | 19/797 (2.4) | 0.66 (0.35 to 1.24) | Antibiotics do not prevent infections |

| Control | 17/640 (2.7) | 6/297 (2.0) | 23/640 (3.6) | |||||

| 20094 (15) | Antibiotics | Fixed effects | Not significant | 25/1465 (1.7) | 6/613 (1.0) | 31/1465 (2.1) | 0.77 (0.47 to 1.27) | Antibiotics are unnecessary |

| Control | 27/1443 (1.9) | 9/452 (2.0) | 36/1443 (2.5) | |||||

| 20105 (11) | Antibiotics | Fixed effects | Not significant | 24/900 (2.7) | 7/657 (1.1) | — | — | No evidence to support or refute antibiotics |

| Control | 25/764 (3.3) | 10/531 (1.9) | — | |||||

| 20116 (12) | Antibiotics | Not stated | Not significant | 25/991 (2.5) | 11/786 (1.4) | 36/991 (3.6) | 1.11 (0.68 to 1.82) | Antibiotics are not necessary |

| Control | 21/946 (2.2) | 11/736 (1.5) | 32/946 (3.4) | |||||

| 20167 (19) | Antibiotics | Random effects | Not significant except for overall infections | 65/2709 (2.4) | 28/1488 (1.9) | 62/1488 (4.2) | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.14) | Antibiotics should not be administered |

| Control | 82/2550 (3.2) | 51/1338 (3.8) | 96/1338 (7.2) | |||||

RCT, randomised controlled trial; SSI, surgical site infection; —, not estimated.

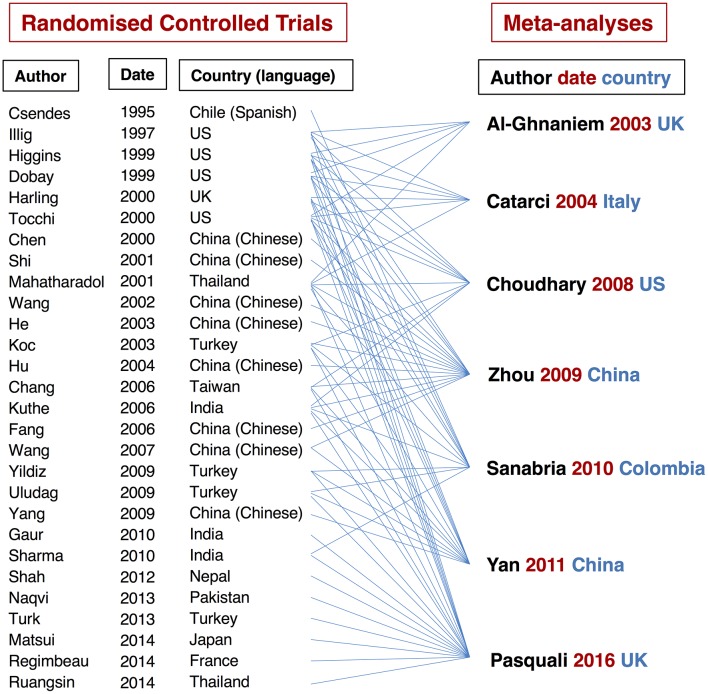

These seven meta-analyses included a total of 28 RCTs and 7065 patients; these RCTs were published between 1995 and 2014.8–35 The relationships between the RCTs and meta-analyses are shown in figure 2. Of these 28 RCTs, one was reported in Spanish8 and eight in Chinese.14 15 17 18 20 23 24 27 All of these trials estimated SSIs and 12 of them also evaluated distant and overall postoperative infections.9 10 13 15 21 24 26 27 29 32–34 Review of these meta-analyses and all of their related RCTs revealed the following issues.

Figure 2.

Relationships between randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses.

First, the number of postoperative infections, including SSIs, distant infections and overall infections, reported in each meta-analysis were meticulously compared with those cited in the original RCTs. This comparison revealed 48 simple miscounts of the number of outcomes in 62–7 of 7 meta-analyses that had examined 15 RCTs.9–11 13 16 18–22 25 28 29 32 34 An example of such a miscount in outcome is that organ/space infections were not included as SSIs in one RCT34 in a meta-analysis.7 Of these 48 miscounts, 23 were disadvantageous and 8 were advantageous regarding antibiotics. The remaining 17 miscounts showed similar results for antibiotics and controls. Details of these miscounts and the relationships between them and the meta-analyses or RCTs are shown in online supplementary appendixes S3.

bmjopen-2017-016666supp003.jpg (1.4MB, jpg)

Second, 6 of the 28 RCTs were inappropriate for inclusion in the meta-analyses.18 20 23 27 28 34 One of these six trials targeted patients with acute cholecystitis rather than low-risk cholecystectomies.34 Additionally, all of the patients in both arms in this RCT had received prophylactic antibiotics. The authors had investigated the efficacy of additional postoperative oral antibiotics after prophylactic administration of antibiotics rather than comparing prophylactic antibiotic treatment with no antibiotic treatment. This RCT had a different study aim and target than the other RCTs. A second trial had insufficient endpoints,28 having failed to include incisional infections but examined only organ/space infections. The incidence of SSIs could therefore not be accurately extracted from this report. The original source of a third trial was not found, even after requesting information from the library of the authors’ institution.18 The study protocols of the remaining three trials were different from those of the other trials.20 23 27 One of their arms was only postoperative administration of antibiotics; thus, the study arms did not appear to be suitable for prophylaxis. These six RCTs were considered inappropriate for these meta-analyses, which were therefore excluded from the current analysis.

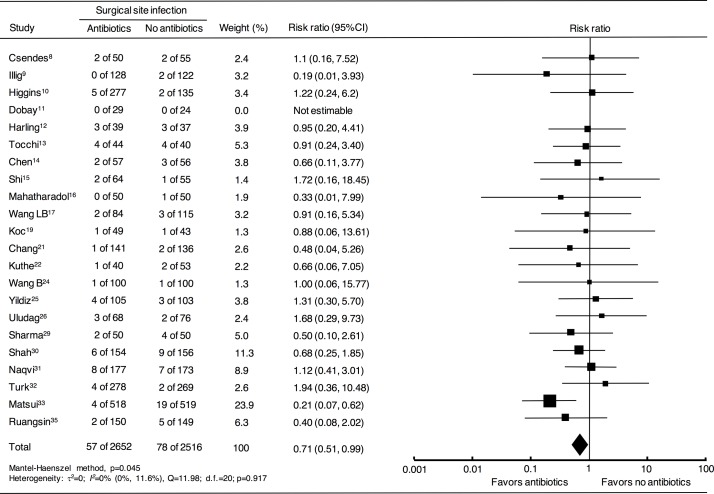

After correcting the above-mentioned miscounts and excluding the six inaccurate trials, the pooled RRs and 95% CIs were recalculated for a total of 5168 patients in 22 RCTs using fixed-effects and random-effects models, yielding results that differed from the conclusions of the original previous meta-analyses (table 2). According to the fixed-effects model, antibiotics significantly reduced the risks of all three categories of postoperative infection: SSIs, distant infections and overall infections. A forest plot of for SSI is shown in figure 3. A significant reduction in distant infections was found with the random-effects model. No heterogeneity was found in SSIs, distant infections or overall infections. Details of the results of the current meta-analysis are shown in online supplementary appendix S4.

Table 2.

Results of reappraisal of pooled risk ratios for postoperative infections after low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy

| Postoperative infections | Total no. of patients (no. of RCTs) |

Fixed-effects model | Random-effects model | ||||

| RR | 95% CI | P | RR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Surgical site infections | 5168 (22) | 0.71 | 0.51 to 0.99 | 0.045 | 0.75 | 0.53 to 1.07 | 0.117 |

| Distant infections | 3170 (10) | 0.37 | 0.19 to 0.73 | 0.004 | 0.45 | 0.22 to 0.92 | 0.028 |

| Overall infections | 3170 (10) | 0.50 | 0.34 to 0.75 | 0.0006 | 0.63 | 0.36 to 1.09 | 0.1 |

RCT, randomised controlled trial; RR, risk ratio.

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing surgical site infection in patients who underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy with or without antibiotics. The fixed-effects model was calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method for meta-analysis. Risk ratios are shown with 95% CIs. Superscript numbers indicate reference numbers.

bmjopen-2017-016666supp004.jpg (1.7MB, jpg)

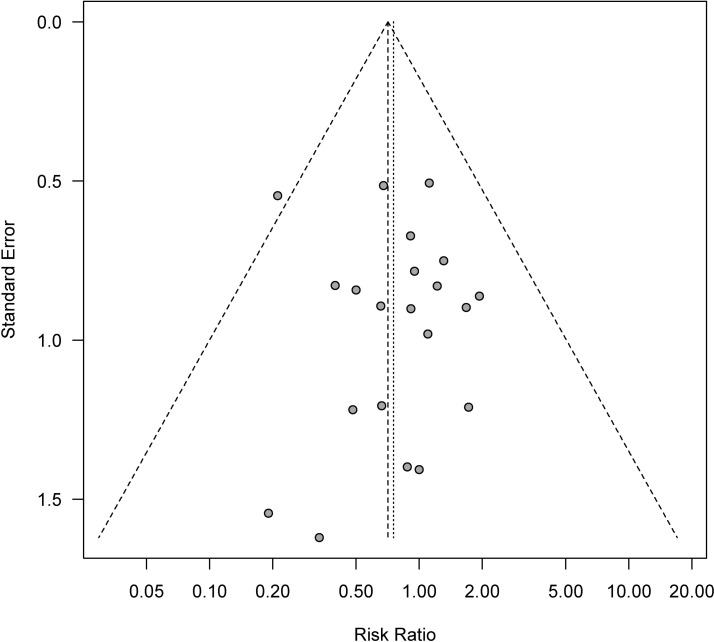

A funnel plot of the available studies is presented in figure 4. Egger’s test yielded a P value of 0.745, indicating there was likely no publication bias. However, the plot did not scatter completely symmetrically, particularly in the lower right aspect, possibly indicating that small studies reporting negative results have not been published. Results of metaregression analyses showed no significant differences regarding publication year, publication language and event rates of antibiotic (SSI Antibiotics ratio) and control groups (SSI Control ratio) (online supplementary appendixes S5). Sensitivity and trial-sequential analyses were not performed because the results of metaregression analyses indicated no statistical differences in these analyses. Additionally, no correlation analyses were performed because several of the RCTs included had not reported conflicts of interest or funding sources.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for determination of publication bias.

bmjopen-2017-016666supp005.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

Discussion

Currently, administration of prophylactic antibiotics to patients undergoing low-risk cholecystectomy is not recommended because of the modest risk of developing an SSI and healthcare costs. Additionally, there is a global campaign to reduce inappropriate antibiotic administration with the aims of minimising further development of microbial resistance and the increasing healthcare costs associated with ageing of the population. However, to date, there is little evidence regarding reducing medical costs and microbial resistance by eliminating antibiotic prophylaxis. Although omitting prophylactic antibiotics is thought to lower medical costs, only one RCT has reported the medical costs of prophylactic antibiotic administration for low-risk cholecystectomies.33 This trial unexpectedly demonstrated that reduction in cost was associated with using prophylactic antibiotics rather than withholding them.

Widespread use of prophylactic antibiotics is generally thought to cause microbial resistance. However, there is little evidence to support this. Microbial resistance may be caused by administering large amounts of therapeutic antibiotic for long periods rather than by short courses of small amounts of prophylactic antibiotics. When postoperative infection does occur, it requires therapeutic use of antibiotics, which may result in microbial resistance. If prophylactic antibiotics can prevent postoperative infections, prophylaxis may reduce microbial resistance by reducing administration of antibiotics therapeutically. Because prolonged antimicrobial therapy is associated with a higher prevalence of resistance, optimal prophylactic antibiotics are required to prevent microbial resistance. Some of the bias against ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics may be attributable to previous overdosage of ‘therapeutic’ antibiotic agents having resulted in microbial resistance.

There are two possible reasons for our results being contrary to those of past meta-analyses. The first is the correction of 48 miscounts of the number of events in 15 RCTs to strictly accord with the definition of SSIs. The second reason is the exclusion of six inappropriate RCTs. The exclusion of one34 of these six trials may have greatly influenced the reversal of previous findings because it was relatively large trial and the greatest number of miscounts of this trial were found in the most recent meta-analysis7 by the current review.

The fixed-effects model is most appropriate when results of a meta-analysis have low heterogeneity, whereas the random-effects model is indicated when there is relatively high heterogeneity.40 The results of the current reappraisal showed no heterogeneity and the fixed-effects model showed that prophylactic antibiotics significantly reduce the incidence of postoperative SSIs, distant infections and overall infections. Moreover, even when the random-effects model was used, the incidence of distant infections was found to have been significantly reduced by prophylaxis. Considering these results, we cannot validly conclude that prophylactic antibiotics are unnecessary.

Most of the previous meta-analyses concluded prophylactic antibiotics were unnecessary because there was no significant difference between the two arms. However, the absence of a statistically significant difference does not validly lead to the conclusion that antibiotics are unnecessary, the only valid conclusion is that there is insufficient evidence to support or refute the efficacy of prophylactic antibiotics. Nevertheless, six of seven meta-analyses rejected prophylactic antibiotics, which in turn introduced a bias into the meta-analyses. Rather than meta-analyses, a large-scale, well-conducted RCT regarding the effect of prophylactic antibiotics on incidence of postoperative infections is needed to reach a definitive conclusion. Such an RCT would require a sample size of around 4500 cases with alpha error of 0.5 and power of 0.8, based on an incidence of SSIs of 2.1% (57/2652) in the antibiotics group versus 3.1% (78/2516) in the control group, as determined by the current study.

One limitation of this study is such ‘super-analysis of analyses’ is also open to bias and error because, even in a ‘super-analysis’, it is impossible to completely remove all bias inherent in the assessed meta-analyses and in their original RCTs. We tried our best to avoid measurement bias by integrating the criteria of the events and precisely recounting the number of events in the meta-analyses and all of the RCTs. In addition, the RCTs that were included in these meta-analyses were performed in many countries with their differing life environments and healthcare systems. Therefore, drawing definitive conclusions about the effects of antibiotic prophylaxis is problematic.

In conclusion, although all the previous meta-analyses except for the most recent one37 concluded that prophylactic antibiotics are unnecessary, no definitive conclusions concerning the effects of antibiotic prophylaxis on postoperative infections can validly be drawn as yet. The effects of antibiotic prophylaxis on medical costs and microbial resistance also remain unclear. Large-scale RCTs regarding prophylactic antibiotics that address the outcomes of microbial resistance and medical costs as well as postoperative infections are required in the future. All possible sources of bias should be eliminated in these RCTs.

bmjopen-2017-016666supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016666supp002.jpg (1.4MB, jpg)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to secretaries Ayaka Fujimoto and Kumi Sakamoto of the Department of Surgery, Kansai Medical University. We also thank Dr Trish Reynolds, MBBS, FRACP, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing the draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to this work. YM, SS, SH and HK all contributed to the conception and design of the review and YM drafted the paper. YM and SS read and screened all retained manuscripts independently. YM, SH, T Kawaura and T Kitawaki rated the quality of the papers. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.83bs4jd.

References

- 1.Al-Ghnaniem R, Benjamin IS, Patel AG. Meta-analysis suggests antibiotic prophylaxis is not warranted in low-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2003;90:365–6. 10.1002/bjs.4033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catarci M, Mancini S, Gentileschi P, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lack of need or lack of evidence? Surg Endosc 2004;18:638–41. 10.1007/s00464-003-9090-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudhary A, Bechtold ML, Puli SR, et al. Role of prophylactic antibiotics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:1847–53. 10.1007/s11605-008-0681-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H, Zhang J, Wang Q, et al. Meta-analysis: antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:1086–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanabria A, Dominguez LC, Valdivieso E, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;12:1–35. 10.1002/14651858.CD005265.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan RC, Shen SQ, Chen ZB, et al. The role of prophylactic antibiotics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy in preventing postoperative infection: a meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2011;21:301–6. 10.1089/lap.2010.0436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquali S, Boal M, Griffiths EA, et al. Meta-analysis of perioperative antibiotics in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2016;103:27–34. 10.1002/bjs.9904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Csendes DA, Silva A, Burdiles P, et al. Profilaxis antibiótica en colecistectomía laparoscópica: studio prospective randomizado. Revista Chilena de Cirugia 1995;47:145–7. In Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Illig KA, Schmidt E, Cavanaugh J, et al. Are prophylactic antibiotics required for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy? J Am Coll Surg 1997;184:353–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins A, London J, Charland S, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: are they necessary? Arch Surg 1999;134:611–4. 10.1001/archsurg.134.6.611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobay KJ, Freier DT, Albear P. The absent role of prophylactic antibiotics in low-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg 1999;65:226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harling R, Moorjani N, Perry C, et al. A prospective, randomised trial of prophylactic antibiotics versus bag extraction in the prophylaxis of wound infection in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2000;82:408–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tocchi A, et al. The need for antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg 2000;135:67–70. 10.1001/archsurg.135.1.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen WJ, Yp M, Jd L. Study on the prophylactic antibiotics in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Zhejiang Med J 2000;22:684–5. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi HX, Zhang XD, Sun T. Evaluation of the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Conc Prac 2001;6:403–4. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahatharadol V. A reevaluation of antibiotic prophylaxis in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai 2001;84:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang LB, Chen WJ, Song XY. Antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective trial. Chinese J Nosocomio 2002;12:845–6. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yd H, Jin XD, Zhang XS. A prospective trial of preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of postoperative infection in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clinical Medicine 2003;23:4–5. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koc M, Zulfikaroglu B, Kece C, et al. A prospective randomized study of prophylactic antibiotics in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1716–8. 10.1007/s00464-002-8866-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mq H, Chen BG, Song XJ. Preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective trial. Chinese Journal of General Surgery 2004;19:639–40. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang WT, Lee KT, Chuang SC, et al. The impact of prophylactic antibiotics on postoperative infection complication in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg 2006;191:721–5. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuthe SA, Kaman L, Verma GR, et al. Evaluation of the role of prophylactic antibiotics in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Trop Gastroenterol 2006;27:54–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fang ZH, Hou YF, Wu W. The value of using antibiotic in perioperative period of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparosco Surg 2006;11:250–1. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang B, Shen LG, Lb L. Necessity of prophylactic antibiotics use in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Educ Gen Prac 2007;5:124–5. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yildiz B, Abbasoglu O, Tirnaksiz B, et al. Determinants of postoperative infection after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 2009;56:589–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uludag M, Yetkin G, Citgez B. The role of prophylactic antibiotics in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg 2009;13:337–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang XY. A prospective clinical study on gallbladder bile bacteria and perioperative use of prophylactic antibiotics in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Taiyuan: Shanxi Medical University, 2009:1–19. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaur A, Pujahari AK. Role of prophylactic antibiotics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Med J Armed Forces India 2010;66:228–30. 10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80043-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma N, Garg PK, Hadke NS, et al. Role of prophylactic antibiotics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and risk factors for surgical site infection: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Infect 2010;11:367–70. 10.1089/sur.2008.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah JN, Maharjan SB, Paudyal S. Routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis in low-risk laparoscopic cholecystectomy is unnecessary: a randomized clinical trial. Asian J Surg 2012;35:136–9. 10.1016/j.asjsur.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naqvi MA, Mehraj A, Ejaz R, et al. Role of prophylactic antibiotics in low risk elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: is there a need? J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2013;25:172–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turk E, Karagulle E, Serefhanoglu K, et al. Effect of cefazolin prophylaxis on postoperative infectious complications in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized study. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2013;15:581–6. 10.5812/ircmj.11111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsui Y, Satoi S, Kaibori M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e106702 10.1371/journal.pone.0106702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regimbeau JM, Fuks D, Pautrat K, et al. Effect of postoperative antibiotic administration on postoperative infection following cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:145–54. 10.1001/jama.2014.7586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruangsin S, Laohawiriyakamol S, Sunpaweravong S, et al. The efficacy of cefazolin in reducing surgical site infection in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2015;29:874–81. 10.1007/s00464-014-3745-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barie PS. Does a well-done analysis of poor-quality data constitute evidence of benefit? Ann Surg 2012;255:1030–1. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182574dd3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang B, Dai M, Zou Z. Safety and efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:921–8. 10.1111/jgh.13246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. The hospital infection control practices advisory committee. guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 1999;20:250–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. London: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. updated Mar 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016666supp003.jpg (1.4MB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-016666supp004.jpg (1.7MB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-016666supp005.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016666supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-016666supp002.jpg (1.4MB, jpg)