Abstract

Objective

To find consensus on appropriate and feasible structure, process and outcome indicators for the evaluation of in-hospital geriatric co-management programmes.

Design

An international two-round Delphi study based on a systematic literature review (searching databases, reference lists, prospective citations and trial registers).

Setting

Western Europe and the USA.

Participants

Thirty-three people with at least 2 years of clinical experience in geriatric co-management were recruited. Twenty-eight experts (16 from the USA and 12 from Europe) participated in both Delphi rounds (85% response rate).

Measures

Participants rated the indicators on a nine-point scale for their (1) appropriateness and (2) feasibility to use the indicator for the evaluation of geriatric co-management programmes. Indicators were considered appropriate and feasible based on a median score of seven or higher. Consensus was based on the level of agreement using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.

Results

In the first round containing 37 indicators, there was consensus on 14 indicators. In the second round containing 44 indicators, there was consensus on 31 indicators (structure=8, process=7, outcome=16). Experts indicated that co-management should start within 24 hours of hospital admission using defined criteria for selecting appropriate patients. Programmes should focus on the prevention and management of geriatric syndromes and complications. Key areas for comprehensive geriatric assessment included cognition/delirium, functionality/mobility, falls, pain, medication and pressure ulcers. Key outcomes for evaluating the programme included length of stay, time to surgery and the incidence of complications.

Conclusion

The indicators can be used to assess the performance of geriatric co-management programmes and identify areas for improvement. Furthermore, the indicators can be used to monitor the implementation and effect of these programmes.

Keywords: co-management, Delphi, evaluation, geriatric medicine, quality, implementation

Strengths and limitations of the study.

Preliminary list of indicators developed based on a systematic literature review.

Inclusion of experts from both Europe and the USA.

Use of RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.

Sample of experts consisted largely of geriatricians, low number of non-medical professionals.

Lack of empirical evidence supporting the indicators.

Introduction

Geriatric co-management programmes are emerging as a potential strategy to manage frail patients on non-geriatrics wards. These programmes are characterised by a shared decision-making and collaboration between non-geriatrics and geriatrics teams focusing on the prevention and management of geriatric-oriented problems and syndromes.1 A promising aspect of this model is that geriatrics teams are directly involved in and have direct control over relevant medical issues, which is associated with improved effectiveness of the comprehensive geriatric assessment approach.2 3 Comprehensive geriatric assessment, a central component in geriatric co-management, is defined as a “multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process to determine the medical, psychological and functional capabilities of an older person with frailty, followed by the implementation of a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and follow-up”.4

A recent systematic review identified a potential effect on better functional status, prevention of complications and reduced length of stay as a result of geriatric co-management, but the quality of evidence was low.5 Most notably, the high risk of bias in primary studies and low effect sizes across outcomes limited strong conclusions. Furthermore, the majority of studies were limited to effect evaluations in orthogeriatric populations, while process evaluations and qualitative data are needed to inform how co-management works and how it should be implemented.

Despite the low level of evidence, co-management programmes are increasingly being implemented6 due to their high face validity and the limited impact of in-hospital geriatric consultation teams.1 7 However, some knowledge gaps remain. First, there is no evidence-based understanding of core interventions that should be implemented for all co-management programmes to have their desired effect.8 Second, there is no framework including both effect and process outcomes for evaluating co-management programmes.9

Indicators can inform how to organise in-hospital geriatric co-management programmes, detail the interventions that have to be implemented and define which components of the programme and its implementation that have to be evaluated.10 Structure indicators refer to ‘health system characteristics that affect the system’s ability to meet the health care needs of individual patients or a community’. Process indicators refer to ‘what the provider did for the patient and how well it was done’. Outcome indicators refer to ‘states of health or events that follow care and that may be affected by health care’.10

In the absence of systematic evidence on how to organise and evaluate geriatric co-management programmes, expert opinion can be a first step to address this evidence gap.11 We therefore aimed to find consensus on structure, process and outcome indicators that are appropriate and feasible to use for the evaluation of geriatric co-management programmes.

Methods

A two-round Delphi study based on a systematic literature review was performed in collaboration with international experts on geriatric co-management. A Delphi study involves several survey rounds in which experts are asked to answer a questionnaire anonymously. Results can include both quantitative data (eg, rating indicators on a numeric scale) and qualitative data (eg, comments explaining the rating or suggestions for new indicators), and these results are reported back to the participants. This iterative process aims to find group consensus in which participants can change their rating based on the feedback of previous survey rounds.11

The first Delphi round was performed from December 2015 to January 2016; the second round from February to March 2016.

Systematic literature review

The study methodology and search strategy has been detailed elsewhere and is available in a review protocol in the PROSPERO database (CRD42015026033).5 12 We searched databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and CENTRAL), reference lists, trial registers and PubMed Central Citations from inception until October 2015. Evaluation studies were included if they reported at least one structure, process or outcome of an in-hospital geriatric co-management programme. Two investigators performed the selection process independently using Endnote and data were tabulated using standardised forms. Discrepancies were resolved using consensus discussion. Data were structured using the Donabedian model of the three dimensions of care: structure, process and outcomes (see the Introduction section for definitions).13

Selection of participants

Participants were required to have a minimum of 2 years of clinical experience with co-management for geriatric in-hospital patients in Europe or the USA. Recruitment strategies included using our own network, sending email invitations through national geriatrics societies, contacting authors who have published or presented on geriatric co-management, and contacting members of special interest groups on geriatric co-management. Potential participants were contacted via email, asked to complete their demographic (name, age, gender, country, state) and professional (affiliation, professional education) information, and to report their experience with co-management. The final participants were purposively selected with an aim to achieve a balanced sample based on profession, experience, gender, age and region. All participants were offered the opportunity to receive a voluntary reimbursement for their participation.

Developing the Delphi questionnaire

A preliminary set of indicators was drafted based on the systematic literature review. First, a long list of quality indicators was drafted, structured according to their typology (ie, pertaining to the structure, process or outcome of co-management programmes) and duplicates were removed. Two investigators experienced in geriatric research (BVG, MD) independently scored these indicators as ‘relevant’, ‘relevant after rephrasing’ or ‘not relevant’ for inclusion in the Delphi questionnaire. A consensus meeting decided which indicators were included and how indicators were rephrased. A questionnaire was drafted in English and piloted by four independent experts (KF, KM, JF, MD) in geriatric research and medicine (who did not participate in the Delphi rounds) to evaluate the face and content validity. A consensus meeting between investigators (BVG, KM, JF, MD) decided the final inclusion of indicators in the Delphi questionnaire.

Finding consensus among participants (Delphi rounds)

Participants were contacted via an email explaining the aim and procedure of the Delphi study. In round one, participants were asked to rate the indicators on a nine-point scale for their (1) appropriateness and (2) feasibility to use the indicator for the evaluation of geriatric co-management programmes. If implemented, appropriate indicators are likely to provide a net benefit to patients and improve patient outcomes.14 Feasibility refers to the measurement of the indicator in clinical practice (and not the feasibility of implementing the indicator). Participants could suggest additional indicators based on their experience and knowledge. These suggested indicators were reviewed by the researchers for their relevance and included in the second round questionnaire based on a group consensus. In round two, participants were presented with quantitative and qualitative feedback on the rating of the indicators using summary statistics at the group level and anonymous qualitative quotes by individual participants. Participants were again asked to rate the appropriateness and feasibility of the indicators for which there was no consensus after round one and the new indicators suggested by the participants. For both rounds, reminders were sent to participants.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the structure, processes and outcomes identified in the literature and participants’ characteristics and their rating of the indicators. Indicators were considered appropriate and feasible based on a median score of seven or higher. Consensus was based on the level of agreement using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.15 In short, agreement is observed if the interpercentile range is smaller than the interpercentile range adjusted for asymmetry. We explored descriptive differences in the level of agreement between experts from the USA and Europe. Data were analysed using SPSS V.20 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Ethics

All participants consented to participate in the study via email. Approval by a local ethics committee was not required as a Delphi study with healthcare professionals is not considered an experiment (Belgian law dated 7 May 2004 related to experiments on human people).

Results

Systematic literature review

A total of 12 794 titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors. A total of 335 full-text articles were independently assessed for eligibility by two authors. A final 44 manuscripts were included for data extraction. Studies were excluded because they did not report the evaluation of an in-hospital co-management programme (n=248), were an abstract (n=66), letter to the editor (n=6) or published in another language (n=3).

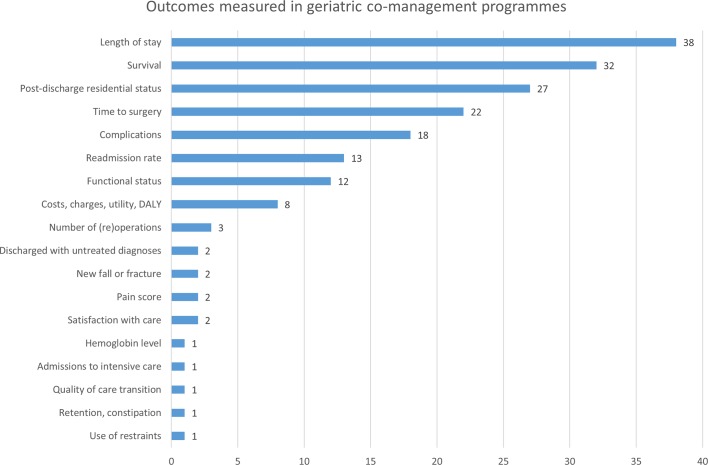

A total of 39 programmes were identified in 44 publications.16–59 The majority of programmes included hip fracture or orthopaedic patients (87%)16–19 21–29 31–37 39–49 52–59 (see online supplementary table S1), including patients aged 65 years or older (74%)16–20 23–27 31–36 38 39 42 43 47–51 53 55–59 (see table 1). Only a minority of programmes used care pathways (38%),16 17 19 20 22 23 25 26 29 32 37–40 42 43 45 48 53 protocols (33%),22–26 29 30 33 34 37–40 48 49 53 standard order sets (21%)19 25 26 29 37 40 42 48 49 53 or educational sessions (15%)20 29 36 39 40 48 59 to support their implementation. The majority of programmes integrated medical review (72%),16–21 23–27 29 30 32 35–42 44–46 48–53 56 discharge planning (69%),18 20 23 24 27–31 33–40 42 45 47–54 56 59 and rehabilitation (77%)16–21 23 24 27–32 35–40 42 45 47–56 59 as intervention components (see table 2). Daily follow-up was provided in 58% of the programmes,16 17 23 25 26 29 32–34 36 37 40 42 46 48–51 53 56 and 44% participated in multidisciplinary team meetings.18–21 23–26 31 36 37 41 50–52 54 56 59 The five most reported outcomes were length of stay, survival, discharge disposition and post-discharge residential status, time to surgery and complications (see figure 1).

Table 1.

Structures identified in co-management programmes

| Structure of co-management programmes | Reported by programmes |

| Patient population of interest | |

| Surgical | 34/39 (87%) |

| Medical | 4/39 (10%) |

| Hospital wide | 1/39 (3%) |

| Team composition | |

| Geriatrician | 38/39 (97%) |

| Geriatric nurse | 8/39 (21%) |

| Physical therapist | 25/39 (64%) |

| Occupational therapist | 14/39 (36%) |

| Social worker | 19/39 (49%) |

| Patient selection for co-management | |

| Age-based characteristics* | |

| Age <65 years† | 10/39 (26%) |

| Age ≥65 years | 18/39 (46%) |

| Age ≥70 years | 5/39 (13%) |

| Age ≥75 years | 3/39 (8%) |

| Geriatric-based characteristics | |

| Functional or cognitive impairment | 2/39 (5%) |

| Multimorbidity, polypharmacy | 1/39 (3%) |

| Screening tool | 2/39 (5%) |

| Programme defined in a care pathway | 15/39 (38%) |

| Evidence-based protocols available | 13/39 (33%) |

| Standard geriatric order sets available | 8/39 (21%) |

| Organisation of educational sessions | 6/39 (15%) |

*Data were missing for three studies.

†The category age <65 years refers to studies recruiting patients aged 26 years or older (n=1), 50 years or older (n=3), 55 years or older (n=1) and 60 years or older (n=5).

Table 2.

Processes identified in co-management programmes

| Processes of co-management programmes | Reported by programmes |

| In-hospital follow-up | 26/39 (67%)* |

| Daily | 15/26 (58%) |

| Thrice weekly | 3/26 (12%) |

| Twice weekly | 3/26 (12%) |

| Weekly or on request | 4/26 (15%) |

| Participation in team meetings† | 17/39 (44%) |

| Daily | 2/17 (12%) |

| Thrice weekly | 1/17 (6%) |

| Twice weekly | 2/17 (12%) |

| Weekly | 12/17 (71%) |

| Medical review/assessment‡ | 28/39 (72%) |

| Cognition | 11/28 (39%) |

| Functional status | 13/28 (46%) |

| Falls | 9/28 (32%) |

| Medication | 4/28 (14%) |

| Nutritional status | 5/28 (18%) |

| Complications | 13/28 (46%) |

| Rehabilitation§ | 30/39 (77%) |

| Discharge planning | 27/39 (69%) |

| Transitional care¶ | 1/39 (3%) |

| Post-discharge follow-up | 16/39 (41%) |

| Referral to community services or outpatient clinics | 9/16 (56%) |

| Home visit | 5/16 (31%) |

| Telephone contact | 2/16 (13%) |

*There was one missing data: study reported ‘rounds with staff’ but did not indicate the frequency.

†Team meetings were defined as case conferences or multidisciplinary meeting in which the geriatrician or geriatrics team interacts with the primary treating physician or other ward staff (eg, registered nurses, physical therapists) to discuss patients included in the co-management programme.

‡Medical review was defined as “the prevention of iatrogenic complications through assessment and delivery of interventions that addresses actual or potential problems identified in the assessment”.68

§Rehabilitation was defined as “assessing the need for physical therapy and providing physical and occupational therapy to prevent or reverse functional decline”.68

¶Transitional care was defined as “a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of health care as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care in the same location”.69

Figure 1.

Outcomes reported by co-management programmes. The bar chart reports the number of programmes reporting a particular outcome. DALY, disability-adjusted life year.

bmjopen-2017-020617supp001.docx (98.3KB, docx)

Delphi study

A total of 63 individuals expressed their interest to participate. Based on a purposive selection of participants, 33 experts were selected, 16 from the USA and 17 from Europe. The majority of participants were medical doctors specialised in geriatric medicine having both clinical and academic experience in co-management (see table 3). Only four nurses and one manager could be included. Participants had a median of 5 years of experience with geriatric co-management, ranging between 2 and 20 years.

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants in Delphi study

| Characteristics | Total sample | USA | Europe |

| Response rate, n (%) | |||

| Round 1 | 30/33 (91) | 16/16 (100) | 14/17 (82) |

| Round 2 | 28/33 (85) | 16/16 (100) | 12/17 (71) |

| Age, median years (range) | 43 (32–62) | 40.5 (32–51) | 46.5 (34–62) |

| Female gender, n (%) | 16/30 (53) | 9/16 (56) | 7/14 (50) |

| Professional education, n (%) | |||

| Medicine | 25/30 (83) | 15/16 (94) | 10/14 (71) |

| Geriatric medicine | 23/30 (77) | 13/16 (81) | 10/14 (71) |

| Medical doctor | 1/30 (3) | 1/16 (6) | 0 |

| Orthopaedic surgeon | 1/30 (3) | 1/16 (6) | 0 |

| Nursing | 4/30 (13) | 0 | 4/14 (29) |

| Management | 1/30 (3) | 1/16 (6) | 0 |

| Academic position, n (%) | |||

| Professor | 6/30 (20) | 3/16 (19) | 3/14 (21) |

| Research associate | 1/30 (3) | 0 | 1/14 (7) |

| Postdoctoral fellow | 2/30 (7) | 0 | 2/14 (14) |

| Doctoral student | 1/30 (3) | 0 | 1/14 (7) |

| Clinical instructor | 13/30 (43) | 12/16 (75) | 1/14 (7) |

| No academic position | 7/30 (23) | 1/16 (6) | 6/14 (43) |

| Co-management background, n (%) | |||

| Clinical | 29/30 (97) | 16/16 (100) | 13/14 (93) |

| Academic | 22/30 (73) | 12/16 (75) | 10/14 (71) |

| Median years of experience with co-management (range) | 5 (2–20) | 4.5 (2–15) | 8.5 (2–20) |

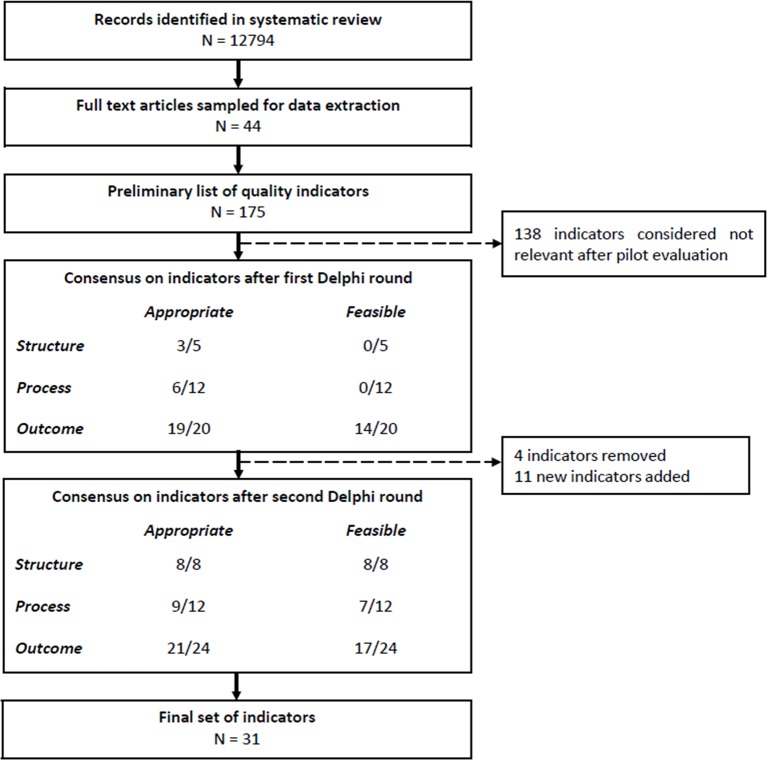

The first round contained 37 indicators. There was consensus on 14 indicators, partial consensus on 14 indicators and no consensus on 5 indicators based on a 90.9% response rate (n=30 experts). Based on the qualitative responses, 4 indicators were removed and 11 new indicators were added to the questionnaire (see online supplementary tables S2 and S3). These new indicators were suggested by the Delphi participants. The second round contained 44 indicators and was sent to the 30 responders of round one. A final consensus on 31 indicators was observed based on an overall response rate of 84.8% (n=28 experts) (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of Delphi process. Consensus was determined based on the level of agreement using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. Indicators were rated on a scale of 1 to 9, and considered appropriate and feasible based on a medium score of 7 or higher. Of the 17 outcome indicators that were considered feasible, 16 were also considered appropriate.

Structure indicators

All eight structure indicators were considered appropriate and feasible (see table 4). Geriatric co-management programmes should include at least a geriatrician, treating physician of the ward, registered nurse or nurse practitioner with geriatric expertise, nursing staff of the ward, physical therapist, occupational therapist and social worker. At least one geriatrics team member should be available on a daily basis. The roles and responsibilities of all professionals participating in the programme should be defined in a care pathway, and their work should be supported by geriatrics order sets and evidence-based protocols for the prevention and management of geriatric syndromes. A screening tool or criteria should be available for including patients into the programme. A geriatrics education programme should be available for all new healthcare professionals at induction and could be repeated yearly for all professionals participating in the co-management programme. Lastly, team meetings should be organised for reviewing the performance of the programme and formulating strategic improvement plans.

Table 4.

Structure indicators for geriatric co-management programmes

| Indicators | Median score (IQR) | |

| All structure indicators were appropriate and feasible* | Appr | Feas |

| A geriatrician, treating physician of the ward, registered nurse or nurse practitioner with geriatric expertise, nursing staff of the ward, physical therapist, occupational therapist and social worker/discharge or case manager is a core member of the geriatric co-management programme. | 7.8 (1.5)† | 8 (2) |

| A member of the geriatrics team is available on a daily basis for patients included in the geriatric co-management programme. | 8 (1) | 8 (1.8) |

| Team meetings for reviewing the performance on indicators associated with the geriatric co-management programme are organised at least once yearly with the aim of evaluating the current performance and formulating strategic improvement plans. | 8 (1) | 8 (1) |

| An educational programme or sessions are organised or facilitated at induction of every new staff member, and at least once a year for all current hospital staff participating in a geriatric co-management programme, focusing on the identification and management of geriatric syndromes. | 8 (2) | 8 (2) |

| A validated screening tool or objective criteria to select patients for the geriatric co-management programme is available to all hospital staff. | 8.5 (1) | 8 (2.8) |

| A multidisciplinary care pathway is available detailing the roles and responsibilities of all hospital staff participating in the geriatric co-management programme. | 9 (1) | 8 (1.8) |

| Evidence-based protocols for the prevention and/or management of cognitive impairment, delirium, depression, hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, pain, palliative care, polypharmacy, malnutrition, falls, osteoporosis, sleep deprivation, functional impairment/mobility and frailty are available to hospital staff participating in the geriatric co-management programme. | 8.3 (1.6)† | 8 (1) |

| Standard geriatric order sets (eg, laboratories, technical investigations) are available to hospital staff participating in the geriatric co-management programme. | 9 (3) | 8 (1) |

*Appropriateness and feasibility was determined by a disagreement index: see online appendix for all indicators that were considered not appropriate or feasible.

†Scores have been averaged for all response options (see text in italic for the different response options): see online appendix for the raw scores.

Appr, appropriateness; Feas, feasibility.

Experts from Europe did consider that using geriatric order sets was appropriate, but there was no consensus within this subgroup.

Process indicators

Seven out of 12 process indicators were considered appropriate and feasible (see table 5). Two indicators were also appropriate but not feasible. Geriatric co-management programmes should start preoperatively or within 24 hours of hospital admission, followed by a geriatric assessment also within 24 hours of hospital admission. A member of the geriatrics team should perform daily patient rounds to see patients in the programme if indicated, and interdisciplinary meetings with the co-management staff should be organised at least twice a week. Patients should have their care preferences documented in an advance care plan and should have a discharge plan documented in their patient record. On hospital discharge, a summary of the hospital care and post-discharge instruction should be sent to the primary care practitioner and/or care facility.

Table 5.

Process indicators for geriatric co-management programmes

| Indicators | Median score (IQR) | |

| Process indicators considered appropriate and feasible with agreement* | Appr | Feas |

| For patients included in the geriatric co-management programme, co-management starts preoperatively or within 24 hours of hospital admission. | 9 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Daily patient rounds are performed by a member of the geriatric team participating in the geriatric co-management programme. | 8 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Collaborative interdisciplinary meetings with the primary treating hospital staff participating in the geriatric co-management programme and a member of the geriatric team are organised to discuss patients included in the geriatric co-management programme at least twice a week. | 7 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Percentage of patients included in the geriatric co-management programme who had a screening or assessment focusing on delirium, dementia, functional status, fall risk, social aspects and environment, comorbidity, pressure ulcer risk, pain, nutritional status, incontinence, urinary tract infection, bowel movement, hearing, vision, sleeping disorder, medication use, frailty and advanced care plans using a validated tool within 24 hours of hospital admission. | 8.5 (1.6)† | 8 (1.8) |

| Percentage of patients included in the geriatric co-management programme who had their care preferences documented in an advance care plan or advanced directive. | 9 (1) | 8 (1.8) |

| Percentage of patients included in the geriatric co-management programme who have a discharge plan documented in their patient record. | 9 (0.3) | 8 (1) |

| Percentage of patients included in the geriatric co-management programme who have a summary of their hospital care and post-discharge instructions send to their primary care practitioner and/or care facility. | 9 (0) | 8 (2) |

*Appropriateness and feasibility was determined by a disagreement index: see online appendix for all indicators that were considered not appropriate or feasible.

†Scores have been averaged for all response options (see text in italic for the different response options): see online appendix for the raw scores.

Appr, appropriateness; Feas, feasibility.

Experts from the USA agreed that verbally communicating the findings of the geriatric assessment, recommendations and care plan to other professionals in the co-management programme is both appropriate and feasible. Experts from Europe considered this appropriate, but not feasible.

Outcome indicators

Sixteen out of 24 outcome indicators were considered appropriate and feasible (see table 6). Five indicators were also appropriate but not feasible. The highest scoring outcome indicators were length of stay, time from admission to surgery, patient satisfaction with hospital care, institutionalisation and the incidence of delirium and wound infections.

Table 6.

Outcome indicators for geriatric co-management programmes

| Indicators | Median score (IQR) | |

| Indicators considered appropriate and feasible with agreement*† | Appr | Feas |

| Mean length of stay in the hospital | 9 (1.3) | 9 (1) |

| Mean time spent in the emergency department‡ | 7 (3) | 8 (2) |

| Mean time from hospital admission to surgery§ | 9 (1.5) | 9 (1.3) |

| Readmission rate within 30 days and 3 months of hospital discharge | 8 (2)¶ | 8 (2) |

| Patient satisfaction with hospital care | 9 (1) | 7 (3) |

| Caregiver satisfaction with hospital care provided for patients included in the geriatric co-management programme | 8.5 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Percentage of patients who were physically restrained during their hospital stay | 9 (2) | 8 (3) |

| In-hospital mortality rate | 9 (2) | 9 (0.3) |

| Percentage of patients admitted to a nursing home on hospital discharge | 9 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Percentage of patients who declined in functional status between hospital admission and hospital discharge | 8 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Percentage of patients who developed delirium | 9 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Percentage of patients who developed a urinary tract infection | 9 (2) | 9 (2) |

| Percentage of patients who developed a wound infection | 9 (1.3) | 9 (1.3) |

| Percentage of patients who developed a pneumonia | 9 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Percentage of patients who developed a sepsis | 9 (2.3) | 9 (2) |

| Percentage of patients who developed a pressure ulcers | 9 (2) | 8 (2) |

*Appropriateness and feasibility was determined by a disagreement index: see online appendix for all scores.

†The denominator relates to patients admitted in the co-management programme.

‡The denominator only includes patients admitted through the emergency department.

§The denominator only includes patient included in a surgical co-management programme.

¶Scores have been averaged for all response options (see text in italic for the different response options): see online appendix for the raw scores.

Appr, appropriateness; Feas, feasibility.

Experts from Europe did consider that length of stay was appropriate, and monitoring physical restraints was feasible, but the level of agreement was insufficient to indicate consensus.

Online supplementary table S4 details the results for all indicators, including those considered not appropriate or feasible or indicators without consensus.

Discussion

This study aimed to find consensus on structure, process and outcome indicators that are appropriate and feasible to use for the evaluation of geriatric co-management programmes using a two-round Delphi study and systematic literature review. We included 33 participants from Europe and the USA and observed consensus on 31 indicators that are considered both appropriate and feasible.

Experts indicated the importance of providing proactive care to frail patients by geriatric care professionals within 24 hours of hospital admission. A central focus of these programmes is the comprehensive geriatric assessment aiming to identify, prevent or manage geriatric syndromes and complications. There was a strong consensus that co-management should focus on areas related to delirium, functional status, falls, pressure ulcers, medication use, comorbidity, nutrition, pain, advance care planning and discharge planning and its communication.

The ability of comprehensive geriatric assessment to improve outcomes has been associated with the ability to implement the treatment plan by the multidisciplinary team.3 There was a strong consensus that co-management programmes should be multidisciplinary and include a geriatrician, treating physician of the non-geriatrics ward, a nurse with geriatrics expertise, physical therapist and social worker. There seems a value for daily co-management, yet experts argued that the frequency should be based on the severity of a specific patient case. Nonetheless, this reflects one of the hallmarks of co-management: shared decision-making with daily communication.60

A standard set of outcome parameters for the evaluation of orthogeriatric co-management programmes was previously developed based on a review of orthogeriatric co-management evaluation studies61 and a consensus development conference.62 Likewise to our results, length of stay, time to surgery, incidence of complications, institutionalisation, readmission rate and mortality were considered important outcomes. However, our Delphi results disagreed with the panellist of the consensus development conference on post-discharge follow-up of outcomes, which were generally not considered feasible by our experts. Furthermore, the appropriateness of post-discharge follow-up declined the longer the endpoint after hospitalisation was defined. This indicates that in-hospital co-management may not be expected to have long-term effects without appropriate follow-up interventions after hospital discharge. Despite long-term follow-up being a key component of comprehensive geriatric assessment,4 this likely reflects a challenge of implementing transitional care in routine practice as there are often no formal relationships between care settings, no financial incentives, inadequate resources and communication, and a lack of time.63

Indeed, many effective interventions in healthcare fail to be implemented in practice.8 Or alternatively, many routine practices are not (as) effective as defined.64 The results from this Delphi study can be used to address this challenge. First, the indicators can be used to measure the current performance of geriatric co-management programmes and identify areas for improvement.65 Second, the indicators can be used to start a new geriatric co-management programme. The structure and process indicators can be considered good geriatric care for frail patients. However, their implementation should be tailored to the local context of the health system, hospital and co-management programme. Third, the indicators can be used to monitor both the effect and the implementation of the programme.66 We therefore advise to monitor both process and outcome indicators when evaluating geriatric co-management programmes. This should be a continuous process and should be followed by strategic improvement plans and re-evaluations.

Methodological considerations

Some considerations should be noted. First, the abstraction of data in the systematic literature review was dependent of the quality of reporting in the primary studies. A recent meta-analysis on geriatric co-management programmes observed a high risk of bias and poor reporting of study methodology in published manuscripts.5 This may result in under-reporting or missing information about particular structures and processes. For example, detailed information about the implementation strategy or process data on the actual delivery of interventions were missing. Second, the results are based largely on the views of medical doctors as we could only recruit four nurses and one manager. The selection of participants was based on those experts who responded to an email invitation. We did not specifically select medical doctors trained in geriatric medicine. For our strategies, we used author lists from publications and abstracts and special interest groups focusing on geriatric co-management. However, it is very likely that geriatricians are more interested in geriatric co-management and therefore more likely to respond to an invitation. The indicators may therefore not fully reflect the interdisciplinary nature of co-management or the economics of implementing geriatrics care models (eg, no economic indicators have been defined). No patients were included because of the technical nature of the indicators and the focus on system characteristics. Nonetheless, patients’ views on the acceptability of implementing indicators should be considered. If not acceptable, the indicators will unlikely result in improved outcomes. Third, because the majority of evidence on geriatric co-management originates from North America and Europe, the results of this study may only be valid for these regions. Furthermore, it should be noted that despite the differences between countries in organising their health systems, there were only minimal differences in appropriateness between regions. Validation of the indicators in other countries is recommended. Fourth, the observed consensus is based on a specific sample of 33 motivated experts, and it is unclear if the same results would have been produced with a different sample of experts. However, a systematic review concluded that RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method has moderate to very good reliability and good construct and predictive validity.67 Fifth, we did not define any threshold standards that should be met when evaluating the indicators, and for many indicators these thresholds are not available. Finally, these indicators are based on expert opinion in the absence of clinical trial data. The strength of the evidence should therefore be considered very low and requires further testing for validity and reliability.14

Conclusion

This Delphi study identified 31 indicators for the evaluation of geriatrics co-management programmes. Patient selection, early inclusion and interdisciplinary care with geriatric expertise based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment are considered key elements of co-management programmes. The indicators can be used to assess the performance of co-management programmes, identify areas for improvement and monitor the implementation and effect of these programmes. Future research should focus on the development of post-discharge outcomes that are feasible to measure, multicentre studies, cluster randomisation and process evaluation to support the scaling up of effective co-management programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable contribution of all Delphi participants who completed all two Delphi rounds: Adam Gordon, Alessandro Morandi, Anna Estehag Johannesson, Ellis Folbert-Brummer, Esteban Franco-Garcia, Fred C Ko, Houman Javedan, Joseph Nicholas, Laurence M Solberg, Lindsay Dingwall, Manisha Parulekar, Mar’ia Loreto Alvarez Nebreda, Margareta Lambert, Meredith Mucha, Merete Gregersen, Mriganka Singh, Mujahid Nadia, Nandkishor V Athavale, Paolo Mazzola, Philipp Bahrmann, Sarah Hobgood, Sarah Howie, Sevdenur Cizginer, Shelley R McDonald, Simon C Mears, Timothy Holahan, Vianka Perez Belyea and Wanda Horn.

The results in this manuscript were presented at the 12th Congress of the European Union Geriatric Medicine Society (2016), Lisbon, Portugal.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study concept and design. BVG and LM contributed to the acquisition of subjects and/or data. BVG, KM, JF and MD contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript and critically revising it for important intellectual content. MD supervised this study.

Funding: This study was funded by the KU Leuven Research Council (REF 22/15/028; G-COACH: geriatric co-management for cardiology patients in the hospital).

Disclaimer: The KU Leuven Research Council had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Competing interests: DAM was co-PI of a John A Hartford Foundation grant for pilot study to disseminate geriatric co-management programmes (8/2015–8/2016). DAM is Secretary of the Board of the International Geriatric Fracture Society (IGFS). JF received honoraria for consultancy services to pharmaceutical companies (Pfizer, GSK, SPMSD). All other authors report no potential conflict of interest.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Collaborators: The G-COACH consortium provides methodological guidance and consists of Anthony Jeuris, Professor Dr Bart Meuris, Bastiaan Van Grootven, Professor Dr Bernadette Dierckx de Casterlé, Professor Dr Christophe Dubois, Els Devriendt, Professor Dr Johan Flamaing, Professor Dr Jos Tournoy, Dr Katleen Fagard, Professor Dr Koen Milisen, Professor Dr Marie-Christine Herregods, Dr Miek Hornikx, Dr Mieke Deschodt and Professor Dr Steffen Rex.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: The G-COACH consortium, Anthony Jeuris, Bart Meuris, Bastiaan Van Grootven, Bernadette Dierckx de Casterlé, Christophe Dubois, Els Devriendt, Johan Flamaing, Jos Tournoy, Katleen Fagard, Koen Milisen, Marie-Christine Herregods, Miek Hornikx, Mieke Deschodt, and Steffen Rex

References

- 1.Deschodt M, Claes V, Van Grootven B, et al. Comprehensive geriatric care in hospitals: the role of inpatient geriatric consultation teams. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;7:Cd006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet 1993;342:1032–6. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92884-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis G, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older hospital patients. Br Med Bull 2004;71:45–59. 10.1093/bmb/ldh033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Grootven B, Flamaing J, Dierckx de Casterlé B, et al. Effectiveness of in-hospital geriatric co-management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2017;46:903–10. 10.1093/ageing/afx051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinetti M. Mainstream or extinction: can defining who we are save geriatrics? J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:1400–4. 10.1111/jgs.14181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deschodt M, Flamaing J, Haentjens P, et al. Impact of geriatric consultation teams on clinical outcome in acute hospitals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 2013;11:48 10.1186/1741-7015-11-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mainz J. Defining and classifying clinical indicators for quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care 2003;15:523–30. 10.1093/intqhc/mzg081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess 1998;2:1–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Grootven B, Flamaing J, Milisen K, et al. Co-management for geriatric in-hospital patients: a systematic review. 2015. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015026033 (accessed October 2017).

- 13.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell SM, Kontopantelis E, Hannon K, et al. Framework and indicator testing protocol for developing and piloting quality indicators for the UK quality and outcomes framework. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:85 10.1186/1471-2296-12-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Auilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adunsky A, Lerner-Geva L, Blumstein T, et al. Improved survival of hip fracture patients treated within a comprehensive geriatric hip fracture unit, compared with standard of care treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:439–44. 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adunsky A, Lusky A, Arad M, et al. A comparative study of rehabilitation outcomes of elderly hip fracture patients: the advantage of a comprehensive orthogeriatric approach. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58:M542–M547. 10.1093/gerona/58.6.M542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortiz AFJ, Vidan AM, Maranon FE, et al. A multidisciplinary and sequential program in elderly patient with hip fracture: a prospective evolution [Spanish]. Trauma Fund 2008;19:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonelli Incalzi R, Gemma A, Capparella O, et al. Continuous geriatric care in orthopedic wards: a valuable alternative to orthogeriatric units. Aging 1993;5:207–16. 10.1007/BF03324157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbaje AI, Maron DD, Yu Q, et al. The geriatric floating interdisciplinary transition team. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:364–70. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02682.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhattacharyya R, Agrawal Y, Elphick H, et al. A unique orthogeriatric model: a step forward in improving the quality of care for hip fracture patients. Int J Surg 2013;11:1083–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biber R, Singler K, Curschmann-Horter M, et al. Implementation of a co-managed Geriatric Fracture Center reduces hospital stay and time-to-operation in elderly femoral neck fracture patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:1527–31. 10.1007/s00402-013-1845-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielza Galindo R, Ortiz Espada A, Arias Muñana E, et al. [Opening of an acute orthogeriatric unit in a general hospital]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2013;48:26–9. 10.1016/j.regg.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cogan L, Martin AJ, Kelly LA, et al. An audit of hip fracture services in the Mater Hospital Dublin 2001 compared with 2006. Ir J Med Sci 2010;179:51–5. 10.1007/s11845-009-0377-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folbert EC, Smit RS, van der Velde D, et al. Geriatric fracture center: a multidisciplinary treatment approach for older patients with a hip fracture improved quality of clinical care and short-term treatment outcomes. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012;3:59–67. 10.1177/2151458512444288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folbert E, Smit R, van der Velde D, et al. [Multidisciplinary integrated care pathway for elderly patients with hip fractures: implementation results from Centre for Geriatric Traumatology, Almelo, The Netherlands]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2011;155:A3197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliot JR, Wilkinson TJ, Hanger HC, et al. The added effectiveness of early geriatrician involvement on acute orthopaedic wards to orthogeriatric rehabilitation. N Z Med J 1996;109:72–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farnworth MG, Kenny P, Shiell A. The costs and effects of early discharge in the management of fractured hip. Age Ageing 1994;23:190–4. 10.1093/ageing/23.3.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Bingham KW, et al. Impact of a comanaged Geriatric Fracture Center on short-term hip fracture outcomes. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1712–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Germain M, Knoeffel F, Wieland D, et al. A geriatric assessment and intervention team for hospital inpatients awaiting transfer to a geriatric unit: a randomized trial. Aging 1995;7:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchrist WJ, Newman RJ, Hamblen DL, et al. Prospective randomised study of an orthopaedic geriatric inpatient service. BMJ 1988;297:1116–8. 10.1136/bmj.297.6656.1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsberg G, Adunsky A, Rasooly I. A cost-utility analysis of a comprehensive orthogeriatric care for hip fracture patients, compared with standard of care treatment. Hip Int 2013;23:570–5. 10.5301/hipint.5000080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.González Montalvo JI, Gotor Pérez P, Martín Vega A, et al. [The acute orthogeriatric unit. Assessment of its effect on the clinical course of patients with hip fractures and an estimate of its financial impact]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2011;46:193–9. 10.1016/j.regg.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.González-Montalvo JI, Alarcón T, Mauleón JL, et al. The orthogeriatric unit for acute patients: a new model of care that improves efficiency in the management of patients with hip fracture. Hip Int 2010;20:229–35. 10.1177/112070001002000214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gregersen M, Mørch MM, Hougaard K, et al. Geriatric intervention in elderly patients with hip fracture in an orthopedic ward. J Inj Violence Res 2012;4:51–7. 10.5249/jivr.v4i2.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grund S, Roos M, Duchene W, et al. Evaluation of length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality in a prospective case series with historical controls. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2015;112:113–9.25780870 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta A. The effectiveness of geriatrician-led comprehensive hip fracture collaborative care in a new acute hip unit based in a general hospital setting in the UK. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014;44:20–6. 10.4997/JRCPE.2014.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harari D, Martin FC, Buttery A, et al. The older persons' assessment and liaison team ’OPAL': evaluation of comprehensive geriatric assessment in acute medical inpatients. Age Ageing 2007;36:670–5. 10.1093/ageing/afm089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harari D, Hopper A, Dhesi J, et al. Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery (’POPS'): designing, embedding, evaluating and funding a comprehensive geriatric assessment service for older elective surgical patients. Age Ageing 2007;36:190–6. 10.1093/ageing/afl163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kates SL, Mendelson DA, Friedman SM. The value of an organized fracture program for the elderly: early results. J Orthop Trauma 2011;25:233–7. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181e5e901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khan R, Fernandez C, Kashifl F, et al. Combined orthogeriatric care in the management of hip fractures: a prospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2002;84:122–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khasraghi FA, Christmas C, Lee EJ, et al. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary team approach to hip fracture management. J Surg Orthop Adv 2005;14:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kristensen PK, Thillemann TM, Søballe K, et al. Can improved quality of care explain the success of orthogeriatric units? A population-based cohort study. Age Ageing 2016;45:66–71. 10.1093/ageing/afv155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leung AH, Lam TP, Cheung WH, et al. An orthogeriatric collaborative intervention program for fragility fractures: a retrospective cohort study. J Trauma 2011;71:1390–4. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821f7e60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher AA, Davis MW, Rubenach SE, et al. Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: the impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:172–80. 10.1097/01.bot.0000202220.88855.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsland D, Chadwick C. Prospective study of surgical delay for hip fractures: impact of an orthogeriatrician and increased trauma capacity. Int Orthop 2010;34:1277–84. 10.1007/s00264-009-0868-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mazzola P, De Filippi F, Castoldi G, et al. A comparison between two co-managed geriatric programmes for hip fractured elderly patients. Aging Clin Exp Res 2011;23:431–6. 10.1007/BF03337767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miura LN, DiPiero AR, Homer LD. Effects of a geriatrician-led hip fracture program: improvements in clinical and economic outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:159–67. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naglie G, Tansey C, Kirkland JL, et al. Interdisciplinary inpatient care for elderly people with hip fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2002;167:25–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sennour Y, Counsell SR, Jones J, et al. Development and implementation of a proactive geriatrics consultation model in collaboration with hospitalists. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:2139–45. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02496.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slaets JP, Kauffmann RH, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. A randomized trial of geriatric liaison intervention in elderly medical inpatients. Psychosom Med 1997;59:585–91. 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Street PR, Hill T, Gray LC. Report of first year’s operation of an ortho-geriatric service. Aust Health Rev 1994;17:61–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suhm N, Kaelin R, Studer P, et al. Orthogeriatric care pathway: a prospective survey of impact on length of stay, mortality and institutionalisation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:1261–9. 10.1007/s00402-014-2057-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swanson CE, Day GA, Yelland CE, et al. The management of elderly patients with femoral fractures. A randomised controlled trial of early intervention versus standard care. Med J Aust 1998;169:515–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tha HS, Armstrong D, Broad J, et al. Hip fracture in Auckland: contrasting models of care in two major hospitals. Intern Med J 2009;39:89–94. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vidán M, Serra JA, Moreno C, et al. Efficacy of a comprehensive geriatric intervention in older patients hospitalized for hip fracture: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1476–82. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wagner P, Fuentes P, Diaz A, et al. Comparison of complications and length of hospital stay between orthopedic and orthogeriatric treatment in elderly patients with a hip fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012;3:55–8. 10.1177/2151458512450708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeltzer J, Mitchell RJ, Toson B, et al. Orthogeriatric services associated with lower 30-day mortality for older patients who undergo surgery for hip fracture. Med J Aust 2014;201:409–11. 10.5694/mja14.00055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuckerman JD, Sakales SR, Fabian DR, et al. Hip fractures in geriatric patients. Results of an interdisciplinary hospital care program. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;274:213–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mendelson DA, Friedman SM. Principles of comanagement and the geriatric fracture center. Clin Geriatr Med 2014;30:183–9. 10.1016/j.cger.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liem IS, Kammerlander C, Suhm N, et al. Literature review of outcome parameters used in studies of Geriatric Fracture Centers. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:181–7. 10.1007/s00402-012-1594-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liem IS, Kammerlander C, Suhm N, et al. Identifying a standard set of outcome parameters for the evaluation of orthogeriatric co-management for hip fractures. Injury 2013;44:1403–12. 10.1016/j.injury.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:549–55. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grol R, Wensing M. Implementation of change in healthcare: a complex problem : Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. Oxford: John Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braspenning J, Hermens R, Calsbeek H, et al. Quality and safety of care: the role of indicators : Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M, Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. Oxford: John & Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lawson EH, Gibbons MM, Ko CY, Cy K, et al. The appropriateness method has acceptable reliability and validity for assessing overuse and underuse of surgical procedures. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1133–43. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fox MT, Persaud M, Maimets I, et al. Effectiveness of acute geriatric unit care using acute care for elders components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2237–45. 10.1111/jgs.12028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:533–6. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020617supp001.docx (98.3KB, docx)