Abstract

Ulvan is a major cell wall component of green algae of the genus Ulva, and some marine bacteria encode enzymes that can degrade this polysaccharide. The first ulvan-degrading lyases have been recently characterized, and several putative ulvan lyases have been recombinantly expressed, confirmed as ulvan lyases, and partially characterized. Two families of ulvan-degrading lyases, PL24 and PL25, have recently been established. The PL24 lyase LOR_107 from the bacterial Alteromonadales sp. strain LOR degrades ulvan endolytically, cleaving the bond at the C4 of a glucuronic acid. However, the mechanism and LOR_107 structural features involved are unknown. We present here the crystal structure of LOR_107, representing the first PL24 family structure. We found that LOR_107 adopts a seven-bladed β-propeller fold with a deep canyon on one side of the protein. Comparative sequence analysis revealed a cluster of conserved residues within this canyon, and site-directed mutagenesis disclosed several residues essential for catalysis. We also found that LOR_107 uses the His/Tyr catalytic mechanism, common to several PL families. We captured a tetrasaccharide substrate in the structures of two inactive mutants, which indicated a two-step binding event, with the first substrate interaction near the top of the canyon coordinated by Arg320, followed by sliding of the substrate into the canyon toward the active-site residues. Surprisingly, the LOR_107 structure was very similar to that of the PL25 family PLSV_3936, despite only ∼14% sequence identity between the two enzymes. On the basis of our structural and mutational analyses, we propose a catalytic mechanism for LOR_107 that differs from the typical His/Tyr mechanism.

Keywords: polysaccharide, catalysis, substrate specificity, structural biology, mutagenesis, carbohydrate processing, crystallography, His/Tyr mechansim, Polysaccharide lyase, Ulvan lyase

Introduction

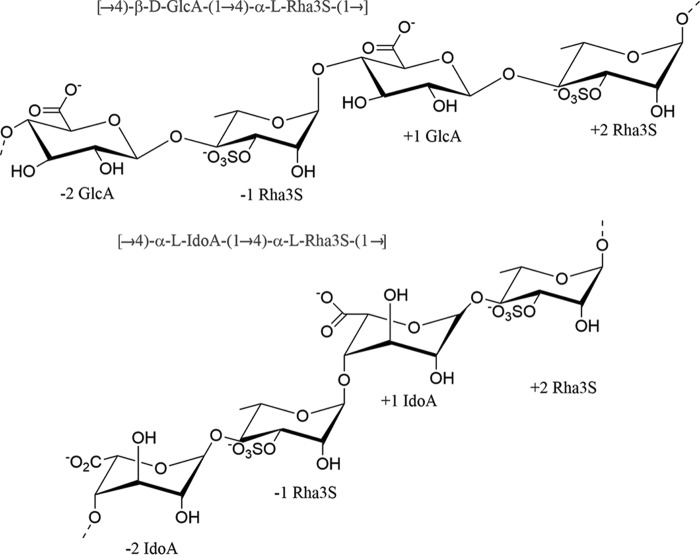

Ulvan is one of the two major cell wall components of marine green algae (genus Ulva and Enteromorpha). It is a complex sulfated polysaccharide composed mainly of 3-sulfated rhamnose (Rha3S),2 glucuronic acid (GlcA), iduronic acid (IdoA), and xylose (1). The common disaccharide repetitive units within the ulvan polysaccharides are [→4)- β-d-GlcA-(1→4)-α-l-Rha3S-(1→] called type A ulvanobiourinic-3-sulfate (A3S) and [→4)-α-l-IdoA-(1→4)-α-l-Rha3S(1→] called type B ulvanobiouronic-3-sulfate (B3S) (1) (Scheme 1). The presence of iduronic acid and sulfated rhamnose differentiates ulvan from other polysaccharides of marine origin and displays similarity with mammalian glycosaminoglycans such as chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid. This distinctive chemical feature makes ulvan an attractive candidate for various biomedical, nanobiotechnological, and drug delivery applications (2–6).

Scheme 1.

The major repeating units of ulvan, [→4)-β-d-GlcA-(1→4)-α-l-Rha3S-(1→] called type A ulvanobiourinic-3-sulfate (A3S) and [→4)-α-l-IdoA-(1→4)-α-l-Rha3S(1→] called type B ulvanobiouronic-3-sulfate (B3S).

Polysaccharides containing uronic acid sugars can be degraded by enzymes utilizing a β-elimination mechanism and are called polysaccharide lyases (PLs). They utilize a β-elimination mechanism to cleave the oxygen–aglycone bond by abstracting the C5 proton, which results in the formation of an unsaturated 4-deoxy-l-threo-hex-4-enopyranosiduronic acid (ΔUA) at the non-reducing end of the oligosaccharide product (7). These enzymes are presently classified into 26 sequence-related families (PL19 was recently renamed GH91) in the CAZy database (www.cazy.org)3 (8). The first enzyme reported to utilize ulvan as a substrate was a lyase from the filamentous fungus Trichoderma sp. GL2 (9) although its main substrate seemed to be oligoglucuronan. Marine bacteria producing enzymes able to degrade ulvan polysaccharides were only recently discovered (10) and the first ulvan lyase from Nonlabens (Persicivirga) ulvanivorans strain PLR was biochemically characterized as an endolytic ulvan lyase (11). The genome of N. ulvanivorans was recently sequenced (12), followed by sequencing the genomes of Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain PLSV (13) and Alteromonas sp. strains LTR and LOR (14). Several of the putative ulvan lyase genes have been recombinantly expressed and partially characterized (15). LOR_107 from Alteromonas sp. strain LOR was confirmed as an ulvan lyase, leading to the establishment of a new polysaccharide lyase family PL24 in the CAZy database (8), which presently contains 29 identified homologs.

We have recently characterized the structure and catalytic mechanism of an ulvan lyase from Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain PLSV, called PLSV_3936. This enzyme belongs to another new polysaccharide lyase family, PL25 (16). PLSV_3936 is folded into a seven-bladed β-propeller and utilizes the His/Tyr-mediated elimination mechanism for catalysis. Moreover, we have described the polysaccharide utilization locus in Alteromonas genome and identified LOR_29 as an ulvan lyase also belonging to the PL25 family (17).

Here we report our investigation of ulvan lyase LOR_107 from Alteromonas (PL24 family). Initial characterization of LOR_107 showed that it preferentially cleaves the bond adjacent to glucuronic acid but has very low or no activity for ulvan segments containing iduronic acid (15). We report the crystal structure of LOR_107 at 1.9-Å resolution. LOR_107 displays a seven-bladed β-propeller fold. The putative active site of LOR_107 was deduced from the structure and confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis of these residues and measurements of their enzymatic activity. The structure of two inactive mutants (R259N and R320N) with a tetrasaccharide substrate soaked into the crystals identified the location of the substrate-binding site and suggested a two-stage substrate binding mechanism. LOR_107 follows the His/Tyr mechanism with some modifications.

Results and discussion

LOR_107 is a founding member of the PL24 polysaccharide lyase family. The secondary structure predictions with PsiPred (18) indicate an all β-strand-containing fold, which suggested a possible similarity to lyases from PL11, PL22, or PL25 families.

Crystal structure of LOR_107

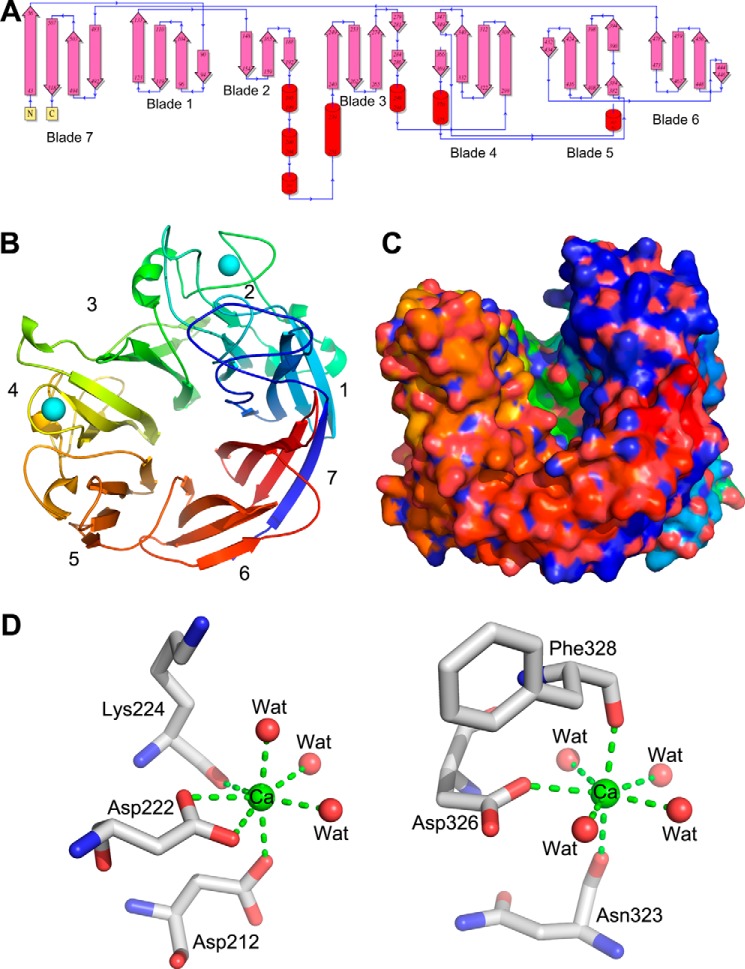

The protein crystallized with two molecules in the asymmetric unit, which are virtually identical and superimpose with a root mean square deviation (r.m.s. deviation) of 0.29 Å for all Cα atoms. The molecule adopts the fold of a seven-bladed β-propeller (Fig. 1A, B). Each propeller consists of four antiparallel β-strands. Blades 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are formed by residues 90–133, 148–208, 240–286, 299–369, 382–434, and 444–478. The 7th blade is formed from three C-terminal β-strands, 483–518, and the 4th β-strands is provided by the N-terminal residues 43–56. The fourth strand in blade 2 is distorted, forming fewer inter-chain hydrogen bonds. This strand is followed by a long loop that is stabilized by a metal ion (see below). The loops joining β-strands extend on either side of the propeller formed by the blades. The loops on one side of the propeller are rather short (bottom of the propeller), whereas the loops on the opposite end are of varied length, with some extending high above the ends of the β-sheets (top of the propeller). Especially, loops within blades 1, 2, 4, 5, and 7 are especially long, whereas those within blades 3 and 6 are much shorter. These long loops delineate a deep canyon on the top surface of the propeller, with high walls on two sides and a lower “neck” located between blades 2 and 4 over the short loops within blade 3 (Fig. 1C). The opposite end of the canyon also has a lower wall formed by blade 6. This canyon is lined with a cluster of highly conserved surface-exposed residues, indicating that this surface defines the substrate-binding site of LOR_107.

Figure 1.

The structure of LOR_107. A, topology diagram of LOR_107. B, schematic representation of LOR_107 structure. The molecule is painted in rainbow colors, from blue at the N terminus to red at the C terminus. Two Ca2 ions are shown as cyan spheres. C, the surface representation showing a long canyon along its top surface with lower rims of the propeller at the ends of the canyon. The view is rotated by 70 degrees along horizontal axis relative to panel B. Color scheme as in panel B. D, the Ca2+ ions in sites 1 (left) and 2 (right). This and other figures were prepared with PyMOL.

Metal and sulfate-binding sites

The presence of metal ions in the structure was indicated by four very strong peaks in the difference electron density map, much larger than what is expected for solvent molecules. Two metal ions are present in each independent molecule at identical positions. We identified these ions as Ca2+ based on their coordination geometry. The Ca2+ ions are located at the periphery of the propeller. Ca2+(1) in site 1 stabilizes the long and winding loop leading from blade 2 to blade 3 and abutting the long loop between distorted strand β4 of blade 2 and β1 of blade 3 (Fig. 1B). This Ca2+ ion is surrounded by seven ligands in a pentagonal bipyramidal coordination. The equatorial ligands are provided by OD1 and OD2 of Asp222, the carbonyl oxygen of Lys224 and two water molecules, whereas the axial ligands are OD2 of Asp212 and another water molecule (Fig. 1D). Ca2+(2) in site 2 is located in blade 4 and stabilizes a long loop between strands β2 and β3. The loop connecting blades 4 and 5 is leaning onto this loop (Fig. 1B). The coordination of this Ca2+ is also pentagonal bipyramidal, with equatorial ligands being OD2 of Asp326 and four water molecules, whereas the axial ligands are carbonyl oxygens of Asn323 and Phe328 (Fig. 1D). Both sites are distant from the conserved residue cluster in the canyon and appear to play a strictly structural role.

In addition to the metal ions, we have identified several sulfate ions in our structure. In particular, two sulfates occupy similar positions in both molecules at the canyon on the top of the propeller. They are surrounded by polar and basic amino acids.

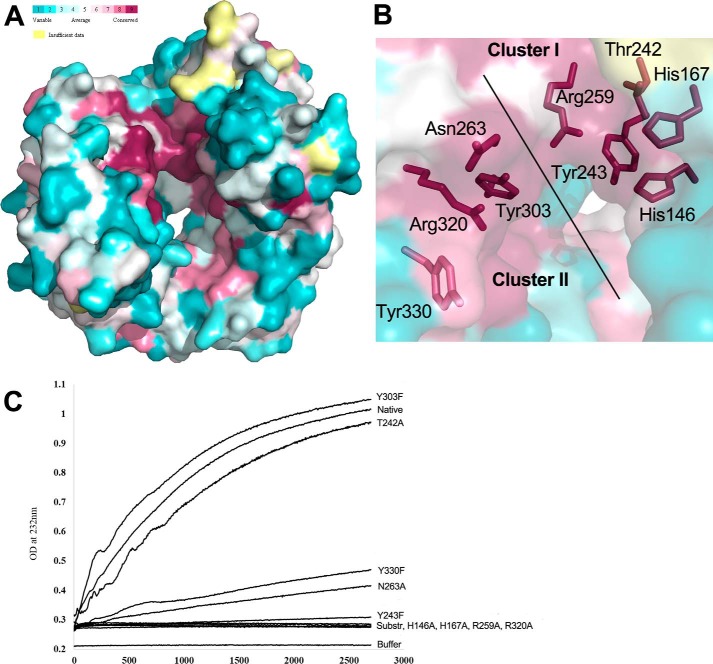

Site-directed mutagenesis of the putative active site and substrate-binding residues

We have investigated the evolutionary conservation of residues in the LOR_107 sequence using the program ConSurf (19). This led to the identification of highly conserved residues on the protein surface that are solvent accessible (Fig. 2A). Two clusters of conserved residues are located on the top side of the propeller and on the sides of the canyon, and contain polar and charged residues that could constitute the active site. Residues His146, His167, Thr242, Tyr243, and Arg259 belong to cluster I and are located on one side of the canyon at the inner edges of blades 2 and 3. Asn263, Tyr303, Arg320, and Tyr330 belong to cluster II and are on the opposite side of the canyon on the edge of blade 4 (Fig. 2B). These residues are absolutely or highly conserved among PL24 sequences. The two clusters are separated by ∼8–10 Å and define the width of the canyon, which is sufficient to accommodate a linear ulvan polysaccharide. We have investigated the contribution of these amino acids to the enzyme activity of LOR_107 by site-directed mutagenesis. The variants containing single mutations, in which each of the above-mentioned residues were changed to an alanine (except Tyr, which was mutated to Phe), were expressed and purified and their activity on the ulvan substrate was measured. The enzyme activity on the ulvan substrate was monitored as a function of time by following the appearance of unsaturated sugar products with a characteristic absorbance at 232 nm (Fig. 2C). The H146A, H167A, R259A, and R320A mutants exhibited a complete loss of activity against the substrate. Conversely, the Y243F mutant showed very low but measurable activity, whereas N263A and Y330F show reduced but readily measurable activity (Fig. 2C). Mutating Thr242 to an alanine led to a very small decrease in activity, whereas the Y303F mutant showed, rather unexpectedly, a small increase in activity relative to the wildtype LOR_107. Together, these data suggested that His146, His167, Arg259, and Arg320 play essential roles in catalysis. Tyr243 is also important in catalysis, because the Y243F mutant showed only residual activity. The remaining investigated side chains most likely affect the organization of the active site or binding of the ulvan substrate.

Figure 2.

Sequence conservation and enzyme activity analysis. A, the surface representation of the enzyme looking at the top of the propeller. The surface is colored by the level of sequence conservation among homologs. The burgundy color marks highly conserved and surface exposed residues. A cluster of highly conserved residues is visible near one end of the canyon. B, the enlarged view of the conserved surface cluster. The surface is shown as semi-transparent and the conserved residues are shown in stick representation. C, activity of wildtype LOR_107 and its mutants. Appearance of unsaturated sugars resulted from the lytic cleavage followed by absorbance at 232 nm for 45 min.

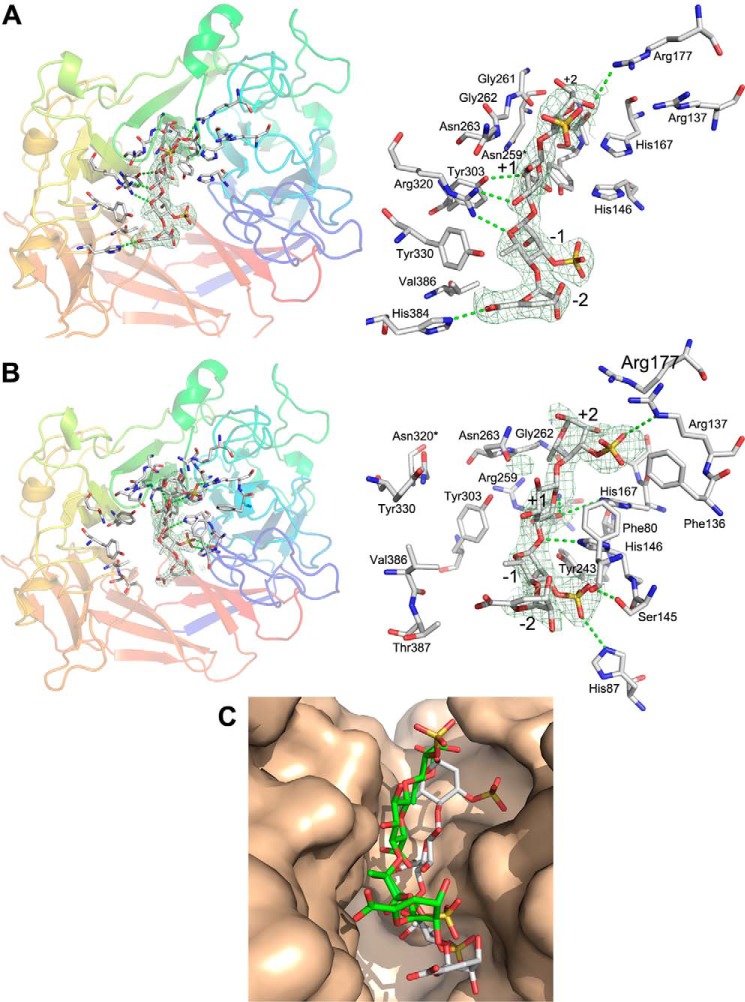

Structure of R259N and R320N mutants with ulvan tetrasaccharide

To capture the substrate within the enzyme we have made several single mutants in which His146, His167, Tyr243, Arg259, and Arg320 were exchanged for other amino acids. Of these, we successfully crystallized R259N and R320N. We introduced the substrate into these crystals through soaking. We have used two tetrasaccharides, 1) the substrate DP4-1, which contains a mixture of ΔUA-Rha3S-GlcA-Rha3Sα/β and ΔUA-Rha3S-IdoA-Rha3Sα/β, and 2) DP4-2 ΔUA-Rha3S-Xyl-Rha3Sα/β, which is a substrate analog that is not cleaved by the enzyme. Of these two tetrasaccharides only DP4-1 was found specifically bound to the enzyme. Following the nomenclature introduced by Davies et al. (20), the sugars on the reducing side of the bond to be cleaved are in positions +1, +2, etc., whereas those on the non-reducing side are in positions −1, −2, etc.

The difference electron density map calculated for the R259N mutant showed an elongated blob of positive density located within the canyon on the top of LOR_107 in proximity to the two clusters of conserved residues. We could fit the entire DP4-1 tetrasaccharide into this electron density (Fig. 3A). The GlcA could be fitted in the +1 position in a chair conformation, whereas IdoA fitted only in a high energy boat conformation. In addition, because LOR_107 shows specificity for cleavage next to GlcA (15) we have modeled GlcA in the +1 position. The substrate is located close to, and makes contacts with, Arg320, Tyr303, and Asn263 (cluster II). Arg320 is in the center of this cluster and its side chain makes hydrogen bonds to O3GlcA at the +1 position and to O5Rha3S at the −1 position. Arg320 is sandwiched between two tyrosine side chains conserved among PL24 sequences, Tyr303 and Tyr330, with the C6Rha3S methyl group abutting the face of Tyr330 aromatic ring. Asn263, located next to Arg320, forms a H-bonds to NH1Arg-320. Asn263 extends over the +1 GlcA, contacting the C2 proton through the aliphatic part of the side chain (Fig. 3A, right panel). In addition, Tyr303 is hydrogen-bonded to the +1 O6BGlcA of the acidic group and the carboxylic O6AGlcA is ∼5 Å from Tyr243. Finally, His384 hydrogen bonds to O6AΔUA in the −2 position and Val386 faces the hydrophobic side of Rha3S at the −1 position. The closest distance of the tetrasaccharide to cluster I residues is to His146 and Tyr243 that are ∼4–5Å from O6AGlcA at the +1 position. Additionally, Arg177 H-bonds to O2Rha3S at the +2 position (Fig. 3A, right panel). The mutated side chain, now Asn259 is rather far from the tetrasaccharide but when this structure is superimposed on the native LOR_107, the side chain of Arg259 extends toward the carboxylic group of GlcA at the +1 position and could form a salt bridge with it.

Figure 3.

Structures of R259N and R320N mutants with tetrasaccharide substrate. A, location of the tetrasaccharide within the canyon on the top of the propeller in R259N (left panel). The omit electron density map of the tetrasaccharide in R259N mutant was contoured at 2.8 σ with the model of the tetrasaccharide. The contacts with the protein are marked with dashed lines. Right panel, a closeup of the tetrasaccharide with the surrounding residues shown in stick representation. A stereo view of the tetrasaccharide fit to the density is shown in Fig. S2. B, location of the tetrasaccharide within the canyon is shown on the top of the propeller in R320N (left panel). The omit electron density map of the tetrasaccharide in the R259N mutant contoured at 2.8 σ is shown. The contacts with the protein are marked with dashed lines: Asn263 changes the conformation clamping the substrate. Right panel, a closeup of the tetrasaccharide with the surrounding residues shown in stick representation. A stereo view of the tetrasaccharide fit to the density is shown in Fig. S3. C, superposition of the tetrasaccharides from R259N and R320N complexes and their location in the substrate-binding canyon. Tetrasaccharide from R259N complex is colored green and R320N complex is colored gray.

The tetrasaccharide in the complex described above is somewhat distant from His146, His167, and Tyr243, which are important for catalysis, suggesting that this binding site is not catalytically competent. We therefore investigated the R320N mutant where the key cluster II contact residue has been changed. In this complex, the substrate is positioned close to cluster I residues (Fig. 3B). Unexpectedly, the Arg259 side chain assumes two conformations in monomer chain A. The minor conformer (occupancy 0.4) corresponds to that in the wildtype enzyme and forms a salt bridge with the acidic group of GlcA at the +1 position, whereas the major conformer (occupancy 0.6, present as the only observed conformation in chain B) points away from GlcA and is directed toward the backbone of Gly262–Asn263. His146 points toward H5GlcA of +1 GlcA and the NE2His-146 is only ∼2 Å away from this proton (∼3 Å from C5GlcA). In addition, this NE2 nitrogen forms a H-bond with the bridging O4 between +1 and −1 sugars. Tyr243 also points toward C5 of GlcA and the bridging O4 but the distances are ∼4 Å, too long for a direct participation in proton transfer. The SO3 of Rha3S at the −1 position fills a hydrophilic pocket made by Ser145, Tyr243, and His146 side chains. Similarly, the SO3 of Rha3S at the +2 position fits into a depression formed by Arg137, Arg177, His167, and the Phe137 side chains. Moreover, Asn263 clamps the tetrasaccharide from the opposite side by H-bonding to the oxygen atom that bridges +1 and +2 sugars. The unsaturated sugar in the −2 position is located near the main chain of Phe80 and Gly81 and makes only van der Waals interactions with the protein (Fig. 3B, right panel).

The R259N and R320N mutations had minimal effect on the overall structure of the protein. However, there is a significant difference in the way the tetrasaccharide substrate binds to these mutants. In the R259N complex the tetrasaccharide substrate binds cluster II side chains, interacting largely with Arg320, and is located at the upper part of the canyon, somewhat distant from the residues affecting catalysis. Nearby Asn263 is H-bonded to Arg320 and directed toward the top of the canyon. In the R320N complex the tetrasaccharide binds deeper in the canyon and approaches the cluster I side chains. The Asn263 changes conformation and extends toward the other wall of the canyon making it narrower and pinning the substrate to the active site.

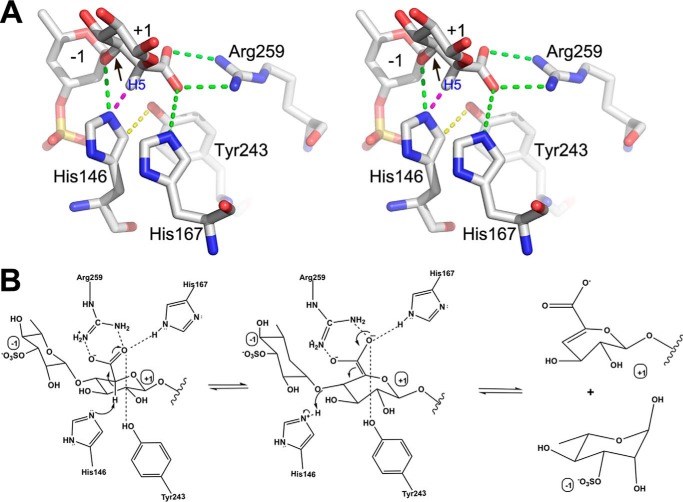

Proposed catalytic mechanism of LOR_107

The importance of Arg320 in cluster II for bond cleavage, combined with the structure of the LOR_107(R259N)–tetrasaccharide complex, suggests that the initial binding of the substrate in the canyon is coordinated by Arg320. This binding site is near the top of the canyon and somewhat distant from the residues essential for catalysis. We postulate that upon initial binding the Arg259 side chain extends toward the acidic group on GlcA in the +1 position and promotes movement of the substrate deeper into the canyon toward cluster I residues. The associated movement of the Asn263 side chain narrows the canyon and locks the substrate in the active site. Indeed, Asn263 side chain plays a role in the catalytic mechanism because its mutation to alanine has a detrimental effect on activity (Fig. 2C).

In the R259N mutant, the Arg259 side chain is absent and thus the substrate remains in the initial binding site. However, when the Arg320 side chain is missing but Arg259 is present (i.e. the R320N mutant), the substrate goes directly to the final destination site near the bottom of the canyon. This binding site is largely preformed when compared with the native LOR_107 structure. In the absence of Arg320 the tetrasaccharide substrate binds in what appears to be a catalytically competent or nearly competent conformation. We postulate that in the wildtype LOR_107 the movement of substrate deeper into the canyon pulls on Arg320 and causes change of the conformation of Asn263, narrowing of the canyon and forcing the substrate into the catalytically competent conformation.

The catalytic mechanism of the polysaccharide lyase family enzyme follows three steps (7): 1) neutralization of the negative charge on carboxylic acid of the uronic acid sugar; this reduces the pKa of the C5 proton; 2) abstraction of the C5 proton by a base; and 3) donation of proton to the leaving group by an acid. A comparison of the native and R320N structures indicates that the role of the neutralizer is performed by Arg259 with the help of His167 (Fig. 4A). We suggest that the presence of His167 is essential for correctly orienting the acidic group on GlcA for the interaction with Arg259. The role of proton abstraction is likely performed by His146, which is properly oriented by stacking with His167 and interaction with Tyr243. The ND2His-146 atom becomes close to both H5GlcA of +1 GlcA and to the bridging O4 (to Rha3S), suggesting that His146 might shuttle the proton directly to the bridging O4 (Fig. 4B). The fact that the Y243F mutant displays residual activity indicates that Tyr243 plays a supporting role but is not directly involved in proton transfer. Therefore, LOR_107 possesses an active site consistent with the His/Tyr mechanism, one of the two mechanisms identified so far in polysaccharide lyases (21, 22) but applies a modification to this mechanism, in which the tyrosine plays a supporting rather than a direct role in proton shuffling (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Proposed catalytic mechanism. A, a stereo view of the close-up of the central disaccharide showing the surrounding side chains. The hydrogen bonds are shown as green dashed lines. The red dashed line indicates the 2.0 Å distance from NE2His-146 to H5 proton of GlcA. The yellow dashed line indicates a short distance of ∼3 Å between His146 and Tyr243. Tyr243 could form a H-bond to ND2 when His146 flips the side chain by 180°. B, the proposed mechanism. Arg259 acts as a neutralizer of the charge of GlcA acidic group. His146 is the most likely candidate to play the role of acid and base by abstracting the proton from C5 of GlcA and donating it to the bridging O4 (If so then multistep). Tyr243 plays a supporting role in properly orienting the imidazole ring of His146. His167 contributes by stacking with His146 and also H-bonding to the acidic group of GlcA for its proper alignment in the active site.

Why then is the R320N mutant inactive? It must reflect the fact that either the substrate position observed in the R320N mutant or the arrangement of catalytic site residues are not fully compatible with catalysis. In this mutant, the Arg259 side chain is predominantly directed away from the substrate and toward the backbone of Gly262–Asn263, likely due to a small rearrangement of a neighboring segment near Asn263. Therefore, Arg259 cannot neutralize the acidic group of +1 GlcA, which in turn, prevents the C5 proton abstraction.

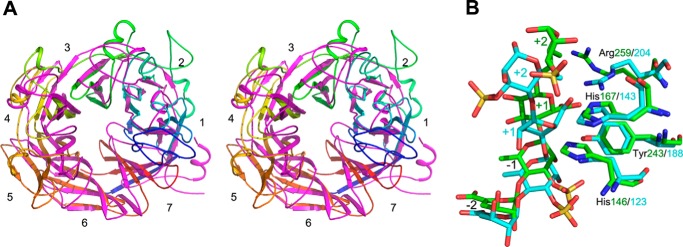

Comparison of LOR_107 and PLSV_3936

PLSV_3936 belongs to the PL25 family and displays the same seven-bladed β-propeller fold as LOR_107. They can be superimposed with a r.m.s. deviation of 1.7 Å for 186 Cα atoms (of ∼440 common) (Swiss-PDBViewer) (23). The strands of the blades superpose well, whereas the loops diverge, particularly the loops at the top of the propeller (Fig. 5A). The canyon on the top of the propeller is somewhat wider in LOR_107 than in PLSV_3936. Both enzymes harbor bound ions, Ca2+ in the case of LOR_107 and Zn2+ for PLSV_3936. The Ca2+ ions in LOR_107 play strictly structural roles and are distant from the active site, whereas the Zn2+ ion in PLSV_3936 is located much closer to the active site and likely contributes not only to the stabilization of one of the loops but also rigidifies the active site area (16).

Figure 5.

Comparison of LOR_107 and PLSV_3936. A, stereo view of a global superposition of LOR_107(R320N) (rainbow) and PLSV_3936(H123N) (magenta) in schematic representation. B, close-up of the active site residues, Arg, Tyr, and two His. LOR_107 has carbons colored green, PLSV_3936 has carbons colored cyan. The superposition is based on best overlap of the backbone atoms of the four residues (active site) shown in the figure and is only slightly different from that shown in panel A. The −1 and −2 sugars adopt similar conformations in both complexes, however, +1 and +2 sugars bind in different conformations, in particular the +2 Rha3S is rotated ∼90° between the two complexes. The different mode of binding is the likely cause of somewhat different roles of the His/Tyr pair in both enzymes.

What is most interesting and unexpected is that the active site residues of LOR_107 are overlapping in this superposition with the active site residues of PLSV_3936 (Fig. 5B). Thus, cluster I residues His146, Tyr243, and Arg259 of LOR_107 correspond to His123, Tyr188, and Arg204 in PLSV_3936, respectively. Moreover, cluster I His167 and Thr242 of LOR_107 superimpose on His143 and Thr187 of PLSV_3936. In this superposition, blades 1–3 and 7 of both proteins superimpose well, whereas blades 4 and 5 in LOR_107 are shifted away from the center of the propeller, widening somewhat the substrate-binding canyon. As a result, cluster II residues in LOR_107 (Asn263, Tyr303, Arg320, and Tyr330) are shifted outside by ∼3 Å with respect to cluster I residues. Moreover, only Tyr303 has a conserved counterpart in the Tyr246 of PLSV_3936. The residue that corresponds spatially to Arg320 in LOR_107 is His264 in PLSV_3936. His264 mediates the Zn2+ binding in PLSV_3936 and mutating this residue leads to precipitation of the protein. But Arg320 is not involved in any metal coordination in LOR_107. Another notable difference is the essential role of His167 in catalysis in LOR_107, whereas mutation of the corresponding His143 in PLSV_3936 does not affect activity.

Structural comparison of substrate binding in PLSV_3936 and R320N shows that the tetrasaccharide binds in a similar region relative to the catalytic residues. The −2 and −1 sugars assume the same conformations. However, there are differences in the +1 and +2 sugars. They assume a different chair pucker, and differ in torsion angles around bonds linking +1 and +2 sugars. This results in the sulfate of the +2 Rha3S sugar pointing in opposite directions in these two binding sites and in somewhat different orientation of +1 GlcA relative to the active site residues (Fig. 5B). It appears that the His/Tyr active site can adjust the function of these two side chains to some changes in substrate orientation and maintain efficient bond cleavage.

Structural comparison with β-propeller fold polysaccharide lyases

There are two other PL families with a β-propeller fold, namely seven-bladed PL22 containing oligogalacturonan lyase and eight-bladed PL11. The superposition of LOR_107 with the PL22 family lyase, oligogalacturonate lyase (PDB code 3PE7 (24)), is less satisfactory (Fig. S1). The best superposition overlaps only 95 Cα atoms with an r.m.s. deviation of 1.7 Å (Swiss-PDBViewer (23)), and encompasses only four blades. In addition, the orientation of the β-strands relative to the central axis of the propeller differs somewhat between these two structures leading to differences in the diameters of the propellers. Importantly, these two lyases appear to use different catalytic mechanisms; the PL22 family utilizes most likely a metal ion-mediated β elimination reaction mechanism (24). The putative active site residues in these two lyases are in a different structural context.

A comparison with the eight-bladed propeller from the PL11 family shows that although the radii of the two barrels are similar, there is only overlap of four blades. Only 92 Cα atoms overlap with an r.m.s. deviation of 1.9 Å.

Conclusions

LOR_107 is representative of the PL24 family. It folds into a seven-bladed β-propeller with an extended and deep substrate-binding canyon located on the top of the propeller. Arg259 and His167 participate in neutralizing the acidic group of the substrate's uronic acid and His146 plays the role of general base and/or general acid. Unlike in other lyases displaying the His/Tyr mechanism, it appears that LOR_107 binds the substrate in a two-stage process with the initial binding coordinated by Arg320. In the final stage, the substrate binds in an atypical way allowing only His146 to form a productive contact with H5GlcA, whereas Tyr243 helps to orient the histidine but is not absolutely essential for activity.

Experimental procedures

Cloning and purification of LOR_107

The gene encoding the enzyme LOR_107 is annotated as WP_052010193 in GenBankTM and as A0A109PTH9_9ALTE in UniProt. The latter sequence has six extra residues on the N terminus. Our numbering follows the NCBI annotation. We have cloned residue 26–522 (without signal peptide) into the expression vector (pET28a) with a C-terminal His6 tag (15). The LOR_107 gene includes several codons that are rare in Escherichia coli and for that reason we have used BL21-codon plus (DE3)-Ripl cells for transformation with the expression vector. An overnight inoculum of the expression strain was subcultured into 1 liter of Terrific Broth medium (ThermoFisher, Canada) supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin and 50 μg of chloramphenicol. Cells were allowed to grow at 37 °C until the absorbance at 600 nm reached 1.5, then the temperature was reduced to 18 °C and protein expression was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. After overnight growth at 18 °C cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4500 × g for 20 min. Harvested cells were resuspended in a lysis buffer (20 mm Tris pH8, 200 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol and 5 mm Imidazole) and lysed using a cell disruptor (Constant Systems Ltd., UK). The soluble fraction was collected by centrifuging at 39,000 × g for 40 min and the recombinant LOR_107 was purified using TALON metal affinity resin (Takara Bio USA). The recombinant protein was eluted with 40 mm imidazole, concentrated and loaded on a S200 (GE Life Sciences) size exclusion column. The protein eluted as a single peak with the apparent molecular weight corresponding to a monomer. The protein was concentrated to 17 mg/ml and submitted to crystallization screening.

Selenomethionine-labeled protein was produced by inhibiting the methionine biosynthesis pathway (25). Briefly an overnight inoculum in 100 ml of LB media was grown at 37 °C. The next day cells were centrifuged and the pellet was resuspended in M9 minimal media. The resuspended cells were used to subculture 1 liter of minimal media supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin and 50 μg of chloramphenicol. Cell growth was continued at 37 °C for 5 to 6 h until it reached OD ∼0.6. Then 100 mg of lysine, phenylalanine, and threonine, 50 mg of isoleucine, leucine, and valine, and 60 mg of l-selenomethionine were added. After 15 min, protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and growth was continued at 20 °C for 16 h. The cells were centrifuged and the selenomethionine-labeled protein was purified in the same way as native protein (except 2 mm DTT was included in the lysis buffer and purification buffer in the selenomethionine-labeled protein purification). The purified protein was concentrated to 20 mg/ml and used for crystallization.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Several conserved residues potentially involved in catalysis and/or substrate binding were selected for mutagenesis. Single mutants H146A, H167A, T242A, Y243F, R259A, N263A, Y303F, R320A, and Y330F were made by the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method (Agilent Technologies Canada Inc., Mississauga) following the manufacturer's instructions and using KOD polymerase. The presence of the designed mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The mutants were expressed in BL21-codon plus (DE3)-Ripl. All the mutants were purified in the same way as the wildtype protein.

Enzymatic activity assay

The activity of wildtype LOR_107 and its various mutants was measured by monitoring the absorption at 232 nm, indicative of the formation of an unsaturated double bond in the hexose ring. Ulvan extracted from ulva rotundata was provided by CEVA (Centre d'étude et de valorisation des algues, Pleubian, France). The polysaccharide was incubated with recombinant N. ulvanivorans ulvan lyase according to Nyvall Collén (11). The oligo-ulvans were purified by size exclusion chromatography using three Superdex 30 columns (2.6 × 60 cm; GE Healthcare) mounted in a series eluting at a flow rate of 1.5 ml min−1 with (NH4)2CO3 as the eluent. The collected fractions were lyophilized. The assay solution was composed of 0.5 mg/ml of ulvan polysaccharide dissolved in 20 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl. 1 μg of the enzyme was added directly to 150 μl of the assay solution to a final concentration of 0.1 μm. The plate was immediately placed in the temperature controlled SpectraMax plate reader (Molecular Devices) and the measurements were carried at 22 °C. The absorbance of the substrate-containing solution was used as a control.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystallization screening of wildtype LOR_107 was carried out using commercial screens in a 96-well sitting drop format at room temperature. The drops contain 0.3 μl of protein solution and 0.3 μl of well solution and were setup using the Gryphon crystallization robot (ArtRobbins Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA). Initial crystals appeared in drops within wells containing 170 mm ammonium sulfate, 85 mm sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 25.5% PEG8K, and 15% glycerol. Optimization by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method led to improved conditions containing 170 mm ammonium sulfate, 85 mm MES, pH 6.5, 23% PEG8K, and 15% glycerol at a protein concentration of 20 mg/ml. Because the crystallization solution already contained glycerol, the crystals were briefly immersed in the well solution and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at the 08ID beamline at the Canadian Light Source synchrotron (26) and processed with the XDS program (27). These crystals diffracted to 1.9-Å resolution and belonged to space group P212121 with unit cell parameters a = 83.6, b = 121.3, c = 123.9 Å. These crystals contain two molecules in the asymmetric unit.

The best crystals of SeMet-labeled protein were grown from 25.5% PEG8K, 170 mm ammonium sulfate, 100 mm MES, pH 6.5, and 17% glycerol. These crystals were briefly transferred to mother liquor and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data to 2.5-Å resolution were collected at the 08ID beamline at the Canadian Light Source and processed using HKL 3000. The crystals belong to space group P212121 with unit cell parameters a = 84.2, b = 121.9, c = 124.3 Å.

Structure determination and refinement

The structure of LOR_107d was solved with the automated structure solving pipeline CRANK2 (28) using data from the SeMet crystal. A total of 20 selenium sites were identified and the initial model contained 839 residues of 1000. This model was refined with the 1.9-Å resolution data from the native crystal. The structure was refined with the Phenix software (29) and manual rebuilding and solvent placement was conducted with the COOT program (30). Two large peaks in a difference electron density map were observed within each molecule, in identical relative positions. Based on the coordination and distances to the liganding atoms these peaks were assigned as Ca2+ ions. The final model contain residues 40 to 520 in both chains, four Ca2+ ions, 14 SO4 ions, five glycerol molecules, one PEG (polyethylene glycol) molecule, and 753 water molecules. The final model was missing residues 26–39 at N terminus and the last two residues at the C terminus. The refinement converged at Rwork = 0.175 and Rfree = 0.200. The stereochemistry of the model was validated with MolProbity (31). The data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and structure refinement statistics

| Crystal form |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native LOR_107 | SeMet LOR_107 | Complex (Arg259) | Complex (Arg320) | |

| Space group | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 | P 21 21 21 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 83.6, 121.3, 123.8 | 84.2, 121.9, 124.3 | 83.05, 121.0, 127.2 | 84.2, 120.7, 127.1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9795 | 0.9794 | 0.9787 | 0.9796 |

| Resolution (Å) | 49.07–1.90 (1.95–1.90) | 46.26–2.5 (2.57–2.50) | 48.89–2.21 (2.26–2.21) | 49.05–2.20 (2.26–2.20) |

| Observed hkl | 1,497,238 | 661,588 | 95,4175 | 344,075 |

| No. unique hkl | 99,600 | 85,354 | 64,618 | 66,028 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.2) | 99.8 (98.1) | 99.0 (87.3) | 99.9 (99.8) |

| Redundancy | 15 (14.9) | 7.8 | 14.8 (13.5) | 5.2 (5.2) |

| Rsym | 0.107 (1.94) | 0.135 (1.35) | 0.105 (1.32) | 0.101 (1.25) |

| CC1/2 | 99.9 (65.2) | 99.8 (64.7) | 100.0 (91.0) | 99.9 (53.6) |

| I/(σI) | 16.56 (1.72) | 13.27 (2.12) | 23.8 (2.63) | 12.93 (1.58) |

| Rwork | 0.175 | 0.20 | 0.20 | |

| Rfree | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Wilson B (Å2) | 33.7 | 36.05 | 39.3 | |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||

| Favored (%) | 96.66 | 94.87 | 95.41 | |

| Allowed (%) | 3.34 | 4.81 | 4.49 | |

| R.m.s. deviation | ||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.008 | |

| Angles (°) | 0.802 | 0.981 | 1.02 | |

| PDB code | 6BYP | 6BYX | 6BYT | |

Crystallization of LOR_107 mutants (R259N, R320N, and Y243F) and their complexes with a tetrasaccharide substrate

The mutant proteins of LOR_107 (R259N, R320N, and Y243F) were purified in the same way as the native protein and concentrated to ∼23 mg/ml. Crystallization of these proteins required some optimization with the final condition being close to that for the native protein (25.5% PEG8000, 170 mm ammonium sulfate, 15% glycerol, 0.1 m MES, pH 6.5).

Crystals of LOR_107 single mutants, R259N, Y243F, and R320N, were soaked for ∼5 h in a solution containing two different tetrasaccharide substrates. The soaking solution containing 3 μl of ∼50 mm tetrasaccharide solution in water mixed with 3 μl of crystallization well solution was placed on a coverslip and equilibrated against 500 μl of well solution. The tetrasaccharides were obtained by enzymatic digestion of ulvan polysaccharide with LOR_107 ulvan lyase (PL24) from Alteromonas LOR sp. (15) and separated by HPLC chromatography. Tetrasaccharide I (DP4-1) contained a mixture of ΔUA-Rha3S-GlcA-Rha3Sα/β and ΔUA-Rha3S-IdoA-Rha3Sα/β with some traces of hexasaccharides. Tetrasaccharide II (DP4-2) was ΔUA-Rha3S-Xyl-Rha3Sα/β. After soaking in tetrasaccharide solution, the crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data of R259N,Y243F were collected at the 08B1 beamline and R320N were collected at the 08ID beamline at the Canadian Light Source. Data were processed with the XDS program. These crystals diffracted to 2.2-Å resolution, they belong to space group P212121 and were isomorphous to the native crystals. A strong positive difference electron density corresponding to the bound substrate was observed in R259N and R320N mutant crystals but not in Y243F mutant soaked in DP4-1. No binding was detected for the crystal soaked in DP4-2. Data collection and refinement statistics are in Table 1.

Author contributions

T. U. and M. K. data curation; T. U. formal analysis; T. U., W. H., M. K., E. B., and M. C. validation; T. U. investigation; T. U. and M. C. visualization; T. U., W. H., M. K., E. B., and M. C. methodology; T. U. writing-original draft; T. U., E. B., and M. C. writing-review and editing; W. H. resources; M. C. conceptualization; M. C. supervision; M. C. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jeremy Lee and David R. Palmer for helpful discussions. We acknowledge the Protein Characterization and Crystallization Facility, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, for access to the crystallization robot. Research described in this paper was performed using beamline 08ID-1 at the Canadian Light Source, which is supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the University of Saskatchewan, the Government of Saskatchewan, Western Economic Diversification Canada, the National Research Council Canada, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

This work was supported by Grant 155375-2012-RGPIN from the Natural Science and Engineering Council (NSERC) (to M. C.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 6BYP, 6BYX, and 6BYT) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- Rha3S

- 3-sulfated rhamnose

- GlcA

- glucuronic acid

- IdoA

- iduronic acid

- PL

- polysaccharide lyases

- ΔUA

- 4-deoxy-l-threo-hex-4-enopyranosiduronic acid

- SeMet

- selenomethionine

- r.m.s.

- root mean square.

References

- 1. Lahaye M., and Robic A. (2007) Structure and functional properties of ulvan, a polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biomacromolecules 8, 1765–1774 10.1021/bm061185q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morelli A., Betti M., Puppi D., and Chiellini F. (2016) Design, preparation and characterization of ulvan based thermosensitive hydrogels. Carbohydrate Polymers 136, 1108–1117 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cunha L., and Grenha A. (2016) Sulfated seaweed polysaccharides as multifunctional materials in drug delivery applications. Marine Drugs 14, 42 10.3390/md14030042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manivasagan P., and Oh J. (2016) Marine polysaccharide-based nanomaterials as a novel source of nanobiotechnological applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 82, 315–327 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.10.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Popa E. G., Reis R. L., and Gomes M. E. (2015) Seaweed polysaccharide-based hydrogels used for the regeneration of articular cartilage. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 35, 410–424 10.3109/07388551.2014.889079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alves A., Sousa R. A., and Reis R. L. (2013) Processing of degradable ulvan 3D porous structures for biomedical applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 101, 998–1006 10.1002/jbm.a.34403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gacesa P. (1987) Alginate-modifying enzymes: a proposed unified mechanism of action for the lyases and epimerases. FEBS Lett. 212, 199–202 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81344-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., and Henrissat B. (2014) The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 10.1093/nar/gkt1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Delattre C., Michaud P., Keller C., Elboutachfaiti R., Beven L., Courtois B., and Courtois J. (2006) Purification and characterization of a novel glucuronan lyase from Trichoderma sp. GL2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 70, 437–443 10.1007/s00253-005-0077-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barbeyron T., Lerat Y., Sassi J. F., Le Panse S., Helbert W., and Collén P. N. (2011) Persicivirga ulvanivorans sp. nov., a marine member of the family Flavobacteriaceae that degrades ulvan from green algae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61, 1899–1905 10.1099/ijs.0.024489-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nyvall Collén P., Sassi J. F., Rogniaux H., Marfaing H., and Helbert W. (2011) Ulvan lyases isolated from the Flavobacteria persicivirga ulvanivorans are the first members of a new polysaccharide lyase family. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42063–42071 10.1074/jbc.M111.271825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kopel M., Helbert W., Henrissat B., Doniger T., and Banin E. (2014) Draft genome sequence of Nonlabens ulvanivorans, an ulvan-degrading bacterium. Genome Announc. 2, e00793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kopel M., Helbert W., Henrissat B., Doniger T., and Banin E. (2014) Draft genome sequence of Pseudo alteromonas sp. strain PLSV, an ulvan-degrading bacterium. Genome Announc. 2, e01257 10.1128/genomeA.00793-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kopel M., Helbert W., Henrissat B., Doniger T., and Banin E. (2014) Draft genome sequences of two ulvan-degrading isolates, strains LTR and LOR, that belong to the Alteromonas genus. Genome Announc. 2, e01081 10.1128/genomeA.01081-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kopel M., Helbert W., Belnik Y., Buravenkov V., Herman A., and Banin E. (2016) New family of ulvan lyases identified in three isolates from the Alteromonadales order. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 5871–5878 10.1074/jbc.M115.673947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ulaganathan T., Boniecki M. T., Foran E., Buravenkov V., Mizrachi N., Banin E., Helbert W., and Cygler M. (2017) New ulvan-degrading polysaccharide lyase family: structure and catalytic mechanism suggests convergent evolution of active site architecture. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 1269–1280 10.1021/acschembio.7b00126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foran E., Buravenkov V., Kopel M., Mizrahi N., Shoshani S., Helbert W., and Banin E. (2017) Functional characterization of a novel “ulvan utilization loci” found in Alteromonas sp. LOR genome. Algal Res. 25, 39–46 10.1016/j.algal.2017.04.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buchan D. W., Minneci F., Nugent T. C., Bryson K., and Jones D. T. (2013) Scalable web services for the PSIPRED protein analysis workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W349–W357 10.1093/nar/gkt381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Landau M., Mayrose I., Rosenberg Y., Glaser F., Martz E., Pupko T., and Ben-Tal N. (2005) ConSurf 2005: the projection of evolutionary conservation scores of residues on protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W299–W302 10.1093/nar/gki370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davies G. J., Wilson K. S., and Henrissat B. (1997) Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J. 321, 557–559 10.1042/bj3210557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garron M. L., and Cygler M. (2014) Uronic polysaccharide degrading enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 28, 87–95 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garron M. L., and Cygler M. (2010) Structural and mechanistic classification of uronic acid-containing polysaccharide lyases. Glycobiology 20, 1547–1573 10.1093/glycob/cwq122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guex N., and Peitsch M. C. (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 10.1002/elps.1150181505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abbott D. W., Gilbert H. J., and Boraston A. B. (2010) The active site of oligogalacturonate lyase provides unique insights into cytoplasmic oligogalacturonate β-elimination. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39029–39038 10.1074/jbc.M110.153981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walden H. (2010) Selenium incorporation using recombinant techniques. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 352–357 10.1107/S0907444909038207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grochulski P., Fodje M. N., Gorin J., Labiuk S. L., and Berg R. (2011) Beamline 08ID-1, the prime beamline of the Canadian Macromolecular Crystallography Facility. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 18, 681–684 10.1107/S0909049511019431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 125–132 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skubák P., and Pannu N. S. (2013) Automatic protein structure solution from weak X-ray data. Nature Commun. 4, 2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Jain S., Kapral G. J., Grosse Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R. D., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., et al. (2011) The Phenix software for automated determination of macromolecular structures. Methods 55, 94–106 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 10.1107/S0907444910007493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., and Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 12–21 10.1107/S0907444909042073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.