Abstract

It is well-established that OxyR functions as a transcriptional activator of the peroxide stress response in bacteria, primarily based on studies on Escherichia coli. Recent investigations have revealed that OxyRs of some other bacteria can regulate gene expression through both repression and activation or repression only; however, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown. Here, we demonstrated in γ-proteobacteriumShewanella oneidensis regulation of OxyR on expression of major catalase gene katB in a dual-control manner through interaction with a single site in the promoter region. Under non-stress conditions, katB expression was repressed by reduced OxyR (OxyRred), whereas when oxidized, OxyR (OxyRoxi) outcompeted OxyRred for the site because of substantially enhanced affinity, resulting in a graded response to oxidative stress, from repression to derepression to activation. The OxyR-binding motif is characterized as a combination of the E. coli motif (tetranucleotides spaced by heptanucleotide) and palindromic structure. We provided evidence to suggest that the S. oneidensis OxyR regulon is significantly contracted compared with those reported, probably containing only five members that are exclusively involved in oxygen reactive species scavenging and iron sequestering. These characteristics probably reflect the adapting strategy of the bacteria that S. oneidensis represents to thrive in redox-stratified microaerobic and anaerobic environments.

Keywords: oxidative stress, gene regulation, DNA binding protein, hydrogen peroxide, bacterial genetics

Introduction

The ability of bacteria to alter gene expression patterns in response to environmental stresses is critical for their survival. This is particularly true about oxidative stress because its causing agents, reactive oxygen species (ROS),2 are omnipresent; in addition to those coming from environments, they are generated endogenously as metabolic by-products of cellular oxygen respiration (1). ROS, including superoxide (O2˙̄), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (•OH), damage biomolecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA (1). When ROS levels exceed safe limits, sensing and responding systems are triggered to coordinately regulate expression of a set of genes to ensure that the ROS concentrations are restrained at an acceptable level and damages are promptly repaired (2). The primary members of these genes encode ROS detoxification enzymes (alkylhydroperoxide reductase (Ahp, renamed NADH peroxidase), catalases, and various peroxidases), iron-sequestering proteins (Dps in particular), and oxidative damage-repairing macromolecules (3).

One of the major ROS sensing and responding systems is OxyR, a LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) consisting of an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) and C-terminal regulatory domain (RD) (2, 4). In model bacterium Escherichia coli, xyR in a tetrameric arrangement is able to activate the transcription of its target genes through the DBD extremely rapidly, within 1–2 min after E. coli cells are exposed to H2O2 (5). The activation of OxyR by H2O2 oxidation is through the formation of an intracellular disulfide bond between the two conserved cysteine residues located in the RD. This induces structural changes of the RD, leading to conformational rearrangement of the DBD to alter the DNA-binding affinity (6, 7). The OxyR-binding motif in E. coli is characterized by four OxyR-binding tetranucleotide sequences spaced by heptanucleotides (consensus, ATAGntnnnanCTAT-N7-ATAGntnnnanCTAT) (8). It has been proposed that each subunit of the OxyR homotetramer specifically binds to one of four tetranucleotide sequences, and because of the spacing, the four subunits interact with four adjacent major grooves on one side of the DNA helix (6, 8).

In recent years, studies into OxyRs of other bacteria have revealed some variations to the E. coli OxyR model. In Deinococcus radiodurans, OxyR is activated by oxidization at the conserved single cysteine residue to a sulfenic acid under peroxide stress (9). In several bacterial species, such as Neisseria, OxyRs function in a dual-control manner (both a repressor and an activator) for major H2O2 scavenging proteins and an activator only for other members of their regulons; as a consequence, OxyR-deficient strains are more resistant to H2O2 (10–13). More surprisingly, Corynebacteria OxyRs function primarily as a repressor for more than 20 genes, including those for ROS detoxification enzymes and iron-sequestering proteins (14–16). In general, the majority of OxyRs are homologous in sequence (∼30–35% in identity) and similar in structure and thus functionally exchangeable (10–16).

Shewanella, a group of Gram-negative facultative γ-proteobacteria, thrive in redox-stratified environments and are renowned for their respiratory versatility (17). Because of the potential application in bioremediation, biogeochemical circulation of minerals, and bioelectricity, these bacteria have been intensively studied, especially the model species Shewanella oneidensis (18). The S. oneidensis OxyR (SoOxyR) resembles those of Neisseria in that it represses expression of catalase gene katB under non-stress conditions but functions as an activator for all of its target genes when cells are challenged by H2O2 (19). Nevertheless, three unexpected phenotypes resulting from the SooxyR disruption were observed (11). First, although the SooxyR mutant under non-stress conditions degrades H2O2 more rapidly, it still carries defects in both viability (plating defect) due to increased sensitivity to H2O2 and growth (18–20), phenotypes reported in bacteria with OxyR being a positive regulator, such as E. coli (21, 22). Second, SoOxyR is also able to respond to organic peroxides, functionally intertwined with OhrR, a regulator specific for organic peroxides (23). Third, SoOxyR is unable to complement the E. coli oxyR mutation and vice versa, although they share a comparable sequence similarity, as mentioned above (11, 13, 19). Hence, SoOxyR apparently mediates cellular response to oxidative stress with unprecedented mechanisms.

In our continued efforts to determine factors accountable for the characteristics of the SoOxyR mutant, we took on in this study to assess the biochemical properties of SoOxyR. We demonstrate that SoOxyR proteins, present in reduced (SoOxyRoxi) and oxidized (SoOxyRred) forms, recognize a single site featured by a combination of the OxyR-binding motif of E. coli and palindromic structure. When present, SoOxyRoxi dictates regulation because of higher affinity for the site than SoOxyRred. Consequently, SoOxyRoxi in excess exerts great inhibitory effects on growth but, interestingly, not on viability. Furthermore, evidence is provided to suggest that the SoOxyR regulon appears contracted significantly, having only five members.

Results

Recombinant His-tagged OxyR proteins exist in reduced and oxidized forms

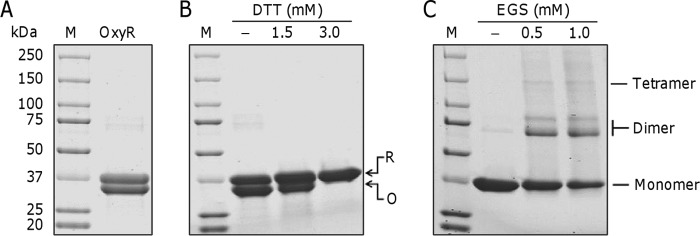

S. oneidensis OxyR, as a H2O2-responsive transcriptional regulator, empowers cells to confront oxidative stress by regulating gene expression through reversible formation of an intermolecular disulfide bond (19). To characterize the biochemical properties of this regulator in more detail, we expressed recombinant SoOxyR with a hexahistidine (His6) tag at the N terminus in E. coli. A large fraction of the protein was soluble, from which the protein was purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography, as revealed as two bands of appropriate molecular mass on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). The scenario suggests that the protein may exist in both reduced and oxidized forms, SoOxyRred and SoOxyRoxi, respectively. To confirm that both bands are SoOxyR proteins, they were excised from an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were analyzed with LC-MS/MS. The result verified their identities in that the peptides matched SoOxyR with 78% coverage of the expected peptides (Fig. S1). To investigate whether oxidation underlies the two bands, the protein samples were treated with the reducing agent DTT of various concentrations and then applied to SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1B). Clearly, SoOxyRoxi can be converted to SoOxyRred by DTT, and complete conversion was achieved with 3.0 mm. We then performed chemical cross-linking assays to evaluate whether SoOxyR forms oligomers at high concentrations (1). Indeed, when treated with the cross-linker ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate) (EGS), oligomerization of SoOxyR, dimerization in particular, was evident (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that SoOxyR, probably functioning in an oligomeric structure, exists in both reduced and oxidized forms.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of purified S. oneidensis OxyR protein. A, SDS-PAGE analysis of Purified recombinant OxyR protein after gel-exclusion chromatography. B, SDS-PAGE analysis of OxyR treated with DTT. The reaction mixtures consisted of 5 μm OxyR protein and DTT at the indicated concentrations. R and O, reduced and oxidized forms of the protein, respectively. C, chemical cross-linking analyses of the purified OxyR protein. The EGS cross-linking reagent was added at the concentrations shown at the top. In all panels, M represents protein standard marker.

SoOxyRoxi always functions as an activator, whereas SoOxyRred is conditional as a repressor

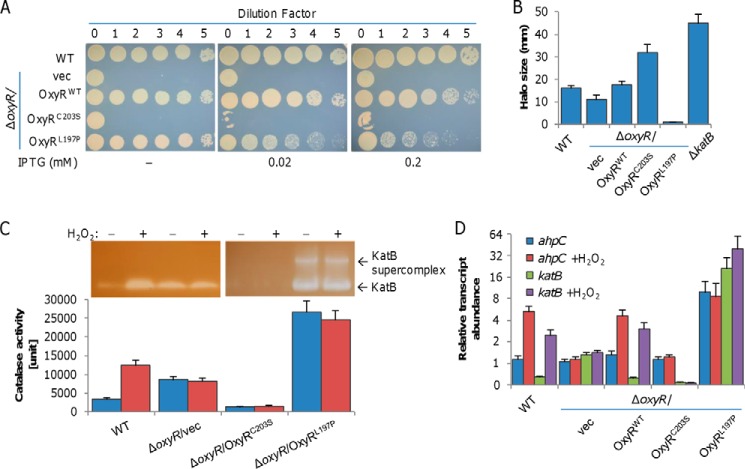

E. coli OxyR senses H2O2 via the reversible formation of disulfide bond between the two conserved cysteines (Cys-199 and Cys-208). In SoOxyR, the counterparts of these two cysteines are Cys-203 and Cys-212, respectively; mutation of either residue to serine locks SoOxyR into the reduced form (19, 24). In addition, the SoOxyRL197P mutant is found to be locked into the oxidized state (25). To determine physiological activity of SoOxyR of different states, we assessed the ability of SoOxyR variants, SoOxyRWT (wildtype), SoOxyRC203S, and SoOxyRL197P, to complement the SooxyR null mutant (ΔSooxyR). We placed the SooxyR alleles under the control of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter Ptac within pHGE-Ptac, and the resulting vectors were introduced into ΔSooxyR. Spotting assays of series dilution cultures were performed to examine the plating defect resulting from the SoOxyR loss on LB plates, as it is the most dramatic phenotype (18, 19). Because the promoter is slightly leaky (26, 27), both SoOxyRWT and SoOxyRL197P produced in the absence of IPTG were sufficient to fully correct the plating defect of ΔSooxyR, but SoOxyRC203S could not. Additionally, induced SoOxyRC203S reduced the viability of ΔSooxyR cells, as evidenced by decreased survival of undiluted cultures on LB plates (Fig. 2A). We also noticed that SoOxyRL197P in excess impeded growth when IPTG was at 0.02 mm, with much more severe effects being observed from 0.2 mm. Overproduced SoOxyRWT appeared to inhibit growth too, but the effect was much less significant.

Figure 2.

Physiological impacts of reduced and oxidized S. oneidensis OxyR proteins. A, droplet assays for viability and growth assessment. Cultures of the indicated strains prepared to contain ∼109 colony-forming units/ml were regarded as undiluted (dilution factor, 0) and were subjected to 10-fold series dilution. Five microliters of each dilution was dropped on LB plates containing IPTG at the indicated concentrations. Results were recorded after a 24-h incubation. Expression of OxyR variants was driven by IPTG-inducible Ptac. B, H2O2 susceptibility by disc diffusion assay. One hundred microliters of cultures was spread onto an agar plate containing 0.02 mm IPTG. Paper discs (diameter, 8 mm) containing 10 μl of 10 m H2O2 were placed on top of the agar. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 16 h prior to analysis. The diameters of the zones of clearing (halo, in millimeters) generated by the peroxides were measured. C, catalase detected by staining and activity assay. Cells of the mid-log phase either directly used (non-treated) or incubated with 0.2 mm H2O2 for 30 min (treated) were used for the assay. Cell lysates containing the same amount of protein were subjected to 10% nondenaturing PAGE (top) and an activity assay (bottom). Staining was performed as described under “Experimental procedures.” For the catalase activity assay, decomposition of H2O2 was measured at 240 nm with absorbance readings taken at 15-s time intervals for a total time of 3.5 min. The unit of activity of each sample is expressed as catalase unit (μmol of H2O2 decomposed per min and per mg of protein). D, analysis of ahpC and katB transcripts by qRT-PCR. Cells of the mid-log phase incubated with 0.2 mm H2O2 for 2 min were used for total RNA extraction. The cycle threshold (CT) values were averaged and normalized against the CT value of the 16S rRNA gene. RTA, relative transcript abundance. In all panels, experiments were performed at least three times, with the average ± S.E. (error bars) of representative results presented.

In parallel, impacts of the SoOxyR variants on H2O2 sensitivity were assessed by a diffusion disc assay, which was carried out in the presence of 0.02 mm IPTG. The results revealed that the ΔSooxyR strain had an inhibition zone smaller (11 mm) than the wildtype (16 mm) (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2), a phenomenon reported before (19). Whereas production of SoOxyRC203S substantially augmented the zone of ΔSooxyR, ∼34 mm in diameter, SoOxyRL197P virtually eliminated the zone. Given that in S. oneidensis, KatB is the catalase predominantly accounting for decomposing H2O2 and therefore resistance (19) (Fig. 2B), we subsequently evaluated the influence of SoOxyR variants on KatB production with catalase staining (Fig. 2C). Production of KatB in the wildtype was responsive to H2O2, being substantially increased when treated with H2O2. Without SoOxyR, S. oneidensis cells lost the ability to respond to H2O2, stably producing KatB at intermediate levels, between those of the wildtype under non-induced and induced conditions because of derepression (explaining why ΔSooxyR has more robust H2O2-scavenging capacity, as shown in Fig. 2B). These data are in excellent agreement with previous findings (18, 19). In ΔSooxyR/SoOxyRL197P, the amount of KatB produced was drastically increased, migrating as the supercomplex on the gel (Fig. 2C). In contrast, KatB in ΔSooxyR/SoOxyRC203S was undetectable either in the treated or untreated cells, indicating that KatB expression is repressed by SoOxyRC203S consistently. For further confirmation, catalase activities of these samples were assayed. The cell extracts (the same as for catalase staining) were mixed with 10 mm H2O2. Decomposition of H2O2 was measured at 15-s time intervals for a total time of 3.5 min to calculate catalase activity. As shown in Fig. 2C, the results correlated well with those of catalase staining.

We further examined impacts of these SoOxyR variants on expression of ahpC that is subject to SoOxyR activation only by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2D). Like katB, ahpC was responsive to H2O2 in the wildtype, with substantially enhanced transcription upon H2O2 treatment. In ΔSooxyR, although the responsiveness was abolished, ahpC differed from katB in that its transcription was down-regulated, indicating that SoOxyR does not function as a repressor for ahpC. This was supported by the fact that SoOxyRC203S failed to elicit detectable impacts on ahpC transcription. As expected, we observed that transcription of ahpC in SoΔoxyR/SoOxyRL197P was substantially up-regulated. Altogether, these results indicate that SoOxyR proteins are present in the reduced and oxidized states, both of which mediate regulation; SoOxyRoxi appears to activate the regulon in general, but SoOxyRred only works for some as a repressor.

Analysis of the promoter region of the katB gene

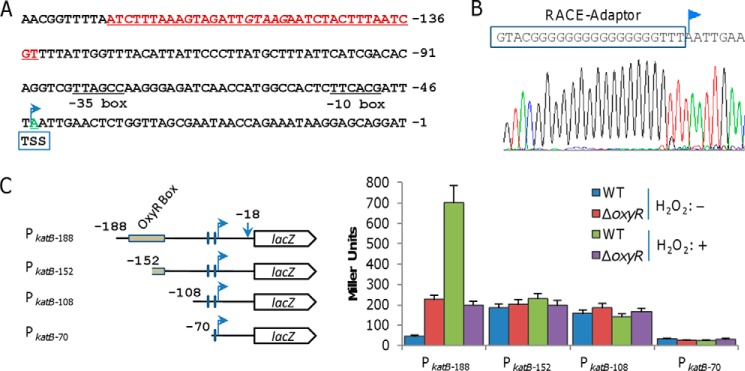

Data presented thus far have demonstrated that katB expression is constitutively activated by SoOxyRL197P and repressed by SoOxyRC203S. We wondered whether SoOxyR interacts with different DNA sites for these two opposing effects on katB expression. To this end, we first mapped the transcription start site (TSS) for the katB gene with 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) (Fig. 3A). The result revealed one major elongated primer product initiating at the position corresponding to A44, the adenine 44 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon ATG (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the S. oneidensis katB promoter region. A, promoter region of the katB gene. The binding site for OxyR is in red and underlined (discussed below in the legend to Fig. 6B), and the transcription start site (TSS) is in green and underlined. The number of nucleotides is relative to the translational starting code. B, determination of the katB transcriptional start site using 5′-RACE. The result of direct DNA sequencing of the 5′-RACE product of the katB gene is shown. C, deletion mapping of the katB regulatory region. Transcriptional fusion constructs are diagramed; coordinates indicate the extent of the regulatory katB region cloned in front of the lacZ reporter gene. The plasmids carrying the constructs were introduced into the relevant strains and integrated on the chromosome. After the antibiotic marker removal, promoter activity was measured by a β-galactosidase assay and is presented as Miller units. Experiments were performed at least three times, with the average ± S.E. (error bars) presented.

We then used an integrative lacZ reporter system to evaluate the activity of a series of katB promoters. DNA fragments of various lengths upstream of the katB coding sequence (from −362, −232, −188, −152, −108, or −70 to −1) were amplified and cloned into the reporter vector pHGEI01 (Fig. 3C). The resulting vectors, verified by sequencing, were introduced into relevant S. oneidensis strains for integration and subsequent removal of the antibiotic marker (28). β-Galactosidase assay revealed that activities of the fragments no less than 188 bp were comparable under any given condition, indicating that they are the same in functionality; to simplify description, only data from 188 bp (PkatB-188) were shown (Fig. 3C). PkatB-188 was responsive to H2O2 in the wildtype but not in ΔSooxyR. Moreover, PkatB-188 activities in the untreated and treated wildtype cells were substantially lower and higher than those in ΔSooxyR, respectively. These data are consistent with the catalase-staining results (Fig. 2C), indicating that this 188-bp fragment contains all elements required for both repression and activation of SoOxyR. In contrast, PkatB-152 and PkatB-108 exhibited considerable activities but were unable to respond to H2O2, indicating that these two promoter fragments are functioning and lack the elements for SoOxyR regulation. The activity of PkatB-70 was barely detectable, indicating that the promoter in the fragment is destroyed. These results suggest that the SoOxyR binding sites lie between −108 and −188 bp upstream of the katB gene.

Mapping the binding sites of OxyRoxi and OxyRred

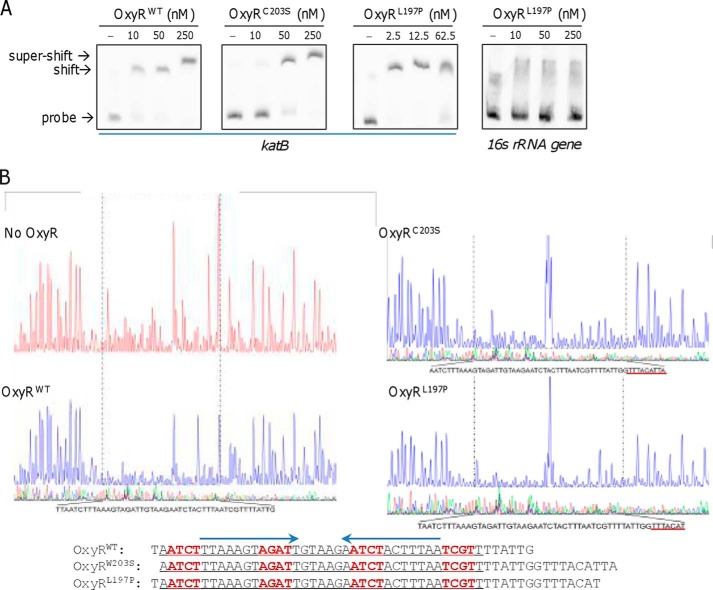

An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed to detect the binding ability of purified His6-tagged SoOxyRWT, SoOxyRC203S, and SoOxyRL197P to a katB promoter fragment covering −300 to −1 in which the predicted OxyR-binding sites are centered. All SoOxyR variants bound well to this fragment in comparison with negative control P16S (promoter sequence of the 16S rRNA gene) (Fig. 4A), indicating that the sites with which SoOxyR variants interact are included. It is noteworthy that SoOxyR variant OxyRL197P had the strongest affinity for the katB promoter, giving an apparent band shift even at 2.5 nm, in contrast to SoOxyRC203S, with which band shift was observed at 50 nm and above.

Figure 4.

Both reduced and oxidized S. oneidensis OxyR proteins interact with the katB promoter region. A, in vitro interaction of His-tagged OxyR variants and the katB promoter sequence revealed by using EMSA. The digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes were prepared by PCR. The EMSA was performed with 1 μm probes and various amounts of proteins as indicated. Nonspecific competitor DNA (2 μm poly(dI·dC)) was included. B, DNase I footprinting analysis of OxyR variants. OxyR variants at 2 μm were used for binding to the 6-FAM–labeled katB promoter fragment. The regions protected by OxyR variants are indicated by a black dotted box and given below for clarity.

To pinpoint the precise binding sequences of SoOxyRWT, SoOxyRC203S, and SoOxyRL197P, a DNA-footprinting experiment with the DNA fragment was performed. The fragments were labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM), incubated with increasing concentrations of SoOxyR variants, and subjected to DNase I digestion. Upon the addition of 4.5 μg of SoOxyRWT, a region of protection corresponding to the area from −126 to −173 with respect to the ATG became clearly evident (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, SoOxyRL197P and SoOxyRC203S protected almost the same region as SoOxyRWT, but the region expanding forward 7–10 bp with respect to the direction of the ATG (Fig. 4B). It was evident that the protected region contains a perfect palindromic sequence, TTAAAGTAGATT(GTAAG)AATCTACTTTAA. In contrast, whether the region also covers a sequence pattern mimicking the OxyR-binding motif of E. coli (ATAGntnnnanCTAT-N7-ATAGntnnnanCTAT) was unknown, as this motif cannot be easily identified by sequence analysis.

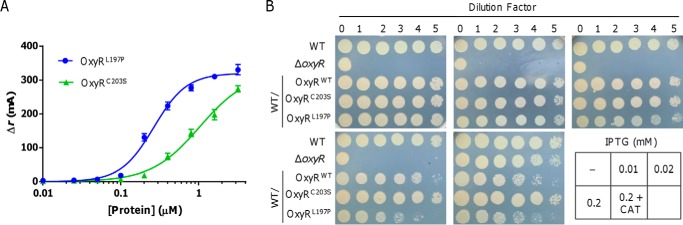

OxyRoxi outcompetes OxyRred in DNA binding

Because EMSAs do not measure binding under equilibrium conditions, fluorescence anisotropy was chosen to examine DNA binding in a quantitative manner at equilibrium (29). Fluorescein-labeled, 60-bp oligonucleotides that contain the entire binding motif were synthesized. As shown in Fig. 5A, the fluorescence anisotropy of the target DNA increased with increasing amounts of SoOxyRL197P and SoOxyRC203S, indicating that both proteins bound to this DNA probe. The ability of these proteins to bind the labeled DNA was clearly different based on the Kd values calculated from the anisotropy data. SoOxyRL197P bound to the probe with a Kd of 0.261 ± 0.03 μm, whereas SoOxyRC203S bound with a Kd of 1.041 ± 0.12 μm. The significant (p < 0.001; t test) difference in Kd values indicates that SoOxyRoxi binds to its target DNA sequence with an affinity about 4 times higher than that of SoOxyRred.

Figure 5.

S. oneidensis OxyRoxi (OxyRL197P) outcompetes OxyRred (OxyRC203S) for binding to the katB promoter. A, fluorescence anisotropy change upon titration of a limiting concentration of 6-FAM–labeled 60-bp katB oligonucleotides (10 nm) with the indicated OxyR variants. Data are plotted as fluorescence anisotropy change values in millianisotrophy units (mA) as a function of protein concentration by using GraphPad Prism version 7 and fit to a model describing a 1:1 protein tetramer, and lines represent simulated curves produced from the average. B, impacts of OxyR variants at varying levels on growth of the wildtype with droplet assays. Production of OxyR variants was driven by Ptac from a single copy on the chromosome. Production level in the presence of 0.02 mm IPTG was equivalent to that of the native oxyR promoter. Catalase was added to differentiate defects in viability and in growth. Experiments were performed at least three times, with the average ± S.E. (error bars) of representative results presented.

Given these differences, we reasoned that high-affinity SoOxyRoxi would overshadow SoOxyRred in physiological impacts when they are coexisting in the cell. To test this, we calibrated promoter activity of SooxyR with the integrative lacZ reporter in comparison with integrative vector carrying Ptac-lacZ (Fig. S3). When Ptac is on the chromosome, its activity in the presence of 0.02 mm IPTG was comparable with that of PoxyR under normal conditions. Constructs of SoOxyRL197P and SoOxyRC203S whose expression was driven by Ptac were then introduced into the wildtype and integrated onto the chromosome. In the presence of IPTG at varying concentrations, impacts of SoOxyRL197P and SoOxyRC203S on growth of the wildtype were assessed. As shown in Fig. 5B, SoOxyRC203S expressed from the IPTG-inducible promoter had undetectable effects on growth, indicating that it could not interfere with SoOxyRWT in regulation. When produced at low levels (IPTG at 0.01 mm), effects of SoOxyRL197P were not evident. However, in the presence of IPTG at 0.02 (equivalent to the oxyR native promoter) and 0.2 mm, SoOxyRL197P inhibited growth, and inhibitory effects increased with levels of the inducer. The impact is on growth rather than viability because the growth defect resulting from SoOxyRL197P production remained in the presence of catalase. These data suggest that SoOxyRoxi outcompetes SoOxyRred in regulation in vivo.

S. oneidensis OxyR-binding motif is complex

Although LTTRs bind to 15–17–bp palindromic regions as dimeric proteins proposed initially, they are active in tetramer form and protect large regions of DNA (up to 60 bp) (4). In line with this, OxyR binding motifs determined to date are up to 50 bp and low in conservation (10, 13, 14, 30, 31). To determine the pattern of the binding motif of SoOxyR, we tested promoter regions of H2O2-responsive genes, including ahpC, ccpA, dps, and katG-1, for in vitro binding of purified SoOxyRL197P protein by EMSA. All of the target DNA probes produced distinct retarded bands when SoOxyR proteins were added (Fig. 6A), validating that SoOxyR directly binds to these promoters. From the promoter regions of katB, katG-1, ahpC, dps, and ccpA, we deduced the SoOxyR consensus sequence with AlignACE and MDScan. Three putative binding motifs were obtained, and they are all palindrome-like sequences and nested (Fig. 6B). Importantly, these motifs reside in the region defined by DNase I footprinting presented above (Fig. 4B). Motif SoOxyR-M13 (13 bp, GATTGTAAGAATC in the katB promoter region) is in the central region, which extends 8 and 13 bp on both ends to form SoOxyR-M29 and SoOxyR-M39, respectively. Although the bioinformatics tools failed to identify a motif resembling the EcOxyR-binding motif, putative tetranucleotide sequences were manually marked out from these sequences (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Binding motifs of S. oneidensis OxyR. A, in vitro interaction of His-tagged OxyRL197P and the various promoter sequences revealed by using EMSA. Experiments were performed in the same manner as Fig. 4A. B, predicted OxyR-binding motifs in S. oneidensis based on the verified promoter sequences. The motifs of the 13- and 29-bp palindromic sequences predicted by AlignACE and MEME are marked with black and blue dashed lines, respectively. Tetranucleotide sequences are underlined based on the E. coli OxyR consensus. C, mutational analysis of the katB regulatory region. Transcriptional fusion constructs are diagramed as in Fig. 4C. In PkatB, the motif of 13 bp is in blue and extended to form the 29-bp motif, the additional nucleotides are in red, and tetranucleotide sequences are underlined. In PkatB mutants, a dot represents the corresponding nucleotide deleted, and nucleotides underlined and in boldface type were mutated. Promoter activity was measured by β-galactosidase assay and is presented as Miller units. Experiments were performed at least three times, with the average ± S.E. (error bars) presented.

To test the pattern of the SoOxyR-binding motif, we constructed a series of promoter mutants, PkatB-M1–M6, to drive expression of E. coli lacZ (Fig. 6C). M1 and M2 were designed to test the importance of the 13-bp central palindromic sequence (SoOxyR-M13), lacking (by deletion) and losing (by point mutations) the feature, respectively. β-Galactosidase assays revealed that M1 lost response to H2O2 both negatively and positively, resembling that of PkatB in ΔSooxyR, whereas M2 retained such ability, albeit significantly compromised (Fig. 6D). M3 aimed to estimate the essentiality of the 7-bp linker between the first two tetranucleotide sequences, whereas M4 altered the structure of the 29-bp palindromic sequence (SoOxyR-M29). The change in the length of the linker (M3) abolished the responding ability of the promoter to H2O2, but M4 largely behaved as the wildtype (Fig. 6D). M5 and M6 were used to test the significance of the first and last tetranucleotide sequences, which have the highest and lowest conservation, respectively. The promoter activities showed that destruction of the first tetranucleotide sequence (M5) largely rendered SoOxyR unable to activate katB expression upon H2O2 treatment, whereas M6 only slightly affected the characteristics of the promoter (Fig. 6D). These data, collectively, suggest that the SoOxyR-binding motif is probably composed of four tetranucleotide sequences separated by a 7-bp linker, the last of which appears less conserved with respective to regulation. Additionally, the palindromic sequence of the central 13-bp but not the extended 29-bp region is critical for regulation.

We then constructed the SoOxyR binding weight matrix based on the experimentally verified SoOxyR-binding sequences (Fig. 6B). Screening for the other SoOxyR binding sites in the S. oneidensis genome was carried out using RSAT (32). In total, 11 putative SoOxyR-binding sites were identified with weight values greater than 7, a cut-off for reliable prediction (Table 1). Except for genes like ahpC, ccpA, dps, katG-1, and katB that have been verified by EMSA, all other genes on this list except for def (polypeptide deformylase) were not reported to be associated with oxidative stress response (1). More importantly, weight values of putative motifs for these genes are relatively low (highest, 14.4); there is a sharp gap between them and those of verified sites, such as katB (lowest, 26.6). Although further investigation is needed, these data suggest that S. oneidensis OxyR possesses an extremely contracted regulon compared with that of E. coli, which consists of more than 30 genes (30).

Table 1.

Top OxyR-binding sites predicted to be in S. oneidensis

Shown are sites shared by two ORFs: SO_2530–SO_2532 (O-6-methylguanine–DNA–alkyltransferase AdaA), SO_3489 (diguanylate cyclase)-SO_3490, SO_0920 (acetyltransferase GNAT family)-SO_0921.

| Locus | Gene | Strand | Location | Binding sequence | Weight | Predicted function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO_1158 | dps | D | 101–63 | AATCTAAATAACAGATTGATAAAATCTATTTTAACCGCT | 28.1 | Dps family protein |

| SO_0958 | ahpC | D | 140–102 | ATTCGACAAAACCGATTAGAACAATAGTTTTTATGCGTT | 27.8 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, C subunit |

| SO_0725 | katG-1 | D | 215–177 | AATCTGTTTTCGCGATTCCAACCATCGGTATTAATCGTT | 27.7 | Catalase/peroxidase HPI |

| SO_2178 | ccpA | D | 115–77 | AATCCACAACAGCGATAGACCCAATCGAAACAAGGCGTT | 27 | Cytochrome c551 peroxidase |

| SO_1070 | katB | D | 171–133 | AATCTTTAAAGTAGATTGTAAGAATCTACTTTAATCGTT | 26.6 | Catalase |

| SO_r012 | rrsD | R | 144–106 | CATCTGCTTAGCAGATTGAAAACATTGATTTAATTCTTT | 14.4 | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| SO_2530 | def | D | 119–81 | AATCTAAAAAACCGATTGTAATGATTTTTATTAAACTAT | 14 | Polypeptide deformylase |

| SO_3490 | D | 137–99 | TATCCTAAACACAAATTGACAGCTTATTATTTAACCGTC | 12 | Protein of unknown function DUF88 | |

| SO_2842 | D | 118–80 | AGTGTAAAATAGCGTTTGTCATAATCGGTTTTTTGGGAT | 9.5 | Peptidase, M23/M37 family | |

| SO_1984 | D | 187–149 | AATTGAGATAATCCATTGACATAATCGATGATTTGCACT | 7.9 | Hypothetical protein | |

| SO_0921 | R | 63–25 | AAACCTTATTCAAGCCTAGCAGACTAGACTTTAGTCGTA | 7.8 | Hypothetical protein |

Discussion

In many Gram-negative bacteria, oxidative stress response is critically mediated by the H2O2-responsive transcriptional regulator OxyR, a member of the LTTR family (2). Upon induction by H2O2, OxyR undergoes a conformational change, allowing the oxidized regulator to function as an activator for genes encoding proteins involved in protection against ROS, a scenario best illustrated in E. coli, on which most of our understanding about this regulator is built (1, 33). However, this turns out to be one side of the regulatory effects of OxyR proteins. In recent years, OxyRs that work as a repressor only or through a dual-control mechanism have been found in Corynebacteria and Neisseria as exemplary bacteria, respectively (9–16). Clearly, the S. oneidensis OxyR resembles those of Neisseria, working as both a repressor and an activator. Nevertheless, it carries novel features that have never been observed from OxyRs studied to date, including compromised resistance to exogenous H2O2, intertwined regulation with OhrR, and non-exchangeable functionality with E. coli OxyR (18–20, 23).

With SoOxyR variants that are locked in reduced and oxidized forms, we verified that SoOxyRoxi exclusively functions as an activator, whereas SoOxyRred as a repressor is conditional, repressing katB expression under non-stress conditions only. In the wildtype cultivated without H2O2, katB is expressed at the basal level, which is so low that KatB catalase activity is barely detectable (Fig. 2C). Although deficient in activation, SoOxyRC203S (SoOxyRred) was fully functional for H2O2-independent repression, a feature consistent with the proposal that SoOxyR acts as a repressor when not in its activated form (19). Depletion of SoOxyR prompts katB expression to a constitutive intermediate level, which can be substantially elevated further when oxidized SoOxyR is present. Clearly, this occurs through direct binding of SoOxyR to the promoter region of katB based on the mutational analysis of the katB promoter variants (Fig. 6).

Although SoOxyR-binding motifs determined to date are low in sequence conservation, a common feature is that they are relatively long (up to 60 bp) (4, 10, 13, 14, 30, 31). For repressor-only Corynebacterium OxyRs, OxyR-binding regions identified by EMSA are ∼50 bp long with multiple T-N7-A motifs of very low sequence similarity, a characteristic for sequences recognized by LTTRs (15). In the case of activator-only and dual-control OxyRs, OxyR-binding motifs are primarily characterized by four tetranucleotide sequences (ATAG) spaced by heptanucleotides (8, 13). It is worth noting that OxyR-binding motifs of some bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, have been proposed to be 15 bp (31). However, these motifs, at least in the case of P. aeruginosa, reside in the middle of 37-bp DNA fragments resembling the E. coli OxyR-binding consensus sequence (8, 31).

Data presented here indicate that S. oneidensis OxyR-binding motifs corroborate the model of four tetranucleotide sequences (ATAG) spaced by heptanucleotides (Fig. 6). Disruption of tetranucleotide sequences except for the last one and the distance in between abolishes both repression and activation. The last tetranucleotide sequence in the katB promoter region is less critical, which may be due to low conservation among target promoters. Intriguingly, there are novel features in S. oneidensis OxyR-binding motifs. Two nested palindromic sequences, 13 and 29 bp, are located in the middle of the sites protected by SoOxyR from DNase I digestion. Whereas the palindrome feature of the 13-bp sequence is important for regulation, the 29-bp one only exhibits a slight impact. Seemingly, these palindromic features are dispensable for repression of SoOxyRred. Nevertheless, the 13-bp palindromic sequence may underlie, at least in part, the functional discrepancy between OxyRs of E. coli and S. oneidensis. However, this merits further investigation.

All OxyR proteins examined to date, regardless of their regulatory effects, are capable of binding to promoter regions of their target genes in both reduced and oxidized forms (8, 13, 15). Given that H2O2 can be generated as a metabolic by-product of cellular oxygen respiration and abiotically (18), cells are living in an environment where a balance between the production and removal of ROS is maintained. Therefore, it is conceivable that OxyR proteins in reduced and oxidized forms co-exist in the cell (Fig. 1). An obvious strategy for OxyR regulation is that OxyRred and OxyRoxi interact with the same site but differ from each other in binding affinity. In E. coli, OxyRoxi has greater affinity than OxyRred to the consensus sequence (8, 33). In this study, we showed that the strategy is also employed by dual-control OxyR. An in vitro binding assay revealed that OxyRoxi exceeds OxyRred in binding affinity more than 4 times (Fig. 5A). In parallel, in vivo analysis demonstrated that OxyRoxi overwhelms OxyRred in its regulatory effects when both proteins are produced at similar levels (Fig. 5B). It is worth mentioning that OxyR in excess negatively influences growth but not viability. We have shown previously that the growth defect of the oxyR mutant is largely attributable to reduced efficacy of oxygen respiration, an indirect effect of the oxyR mutation (20). We speculate that the same mechanism accounts for the growth inhibition of excessive OxyR; efforts to test this notion are under way.

The size of the OxyR regulon varies greatly, ranging from dozens (most bacteria in which the subject has been studied) to over 100 (P. aeruginosa) (31). Among the OxyR-binding sites predicted by RSAT (Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools) (32), five verified members of the regulon are on the top, far above the remaining several based on RSAT weight values. This implies that the regulon of S. oneidensis OxyR is probably small. On the contrary, a microarray analysis of S. oneidnesis cells in response to H2O2-induced oxidative stress has revealed that a vast number of genes are differentially transcribed (19). This indicates that oxidative stress imposes a global impact on gene expression mostly in an indirect manner. Most significantly, those associated with iron/heme biology except for Dps and thioredoxin/glutaredoxin systems involved in OxyR reduction, two groups of well-known OxyR-dependent genes in E. coli and many other bacteria, are not affected by the OxyR loss in S. oneidnesis (19, 30–31).

The physiological relevance of why the OxyR regulon contracts so much is intriguing. It is tempting to suggest that this may be associated with redox-stratified niches where Shewanella thrive. As Shewanella respire an array of electron acceptors, mostly under microaerobic or anaerobic conditions, endogenous and exogenous ROS may not often amount to life-threatening levels. As such, these bacteria evolve a concise and sufficient protection system against oxidative stress in their living environments. In line with this, although small, the regulon contains CcpA, cytochrome c551 peroxidase, which substantiates H2O2 removal under anaerobic conditions but is dispensable under aerobic conditions (34).

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study can be found in Table 2. Information about all of the primers is available upon request. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise noted. E. coli and S. oneidensis were grown in lysogeny broth (LB, Difco, Detroit, MI) under aerobic conditions at 37 and 30 °C for genetic manipulation. When necessary, the growth medium was supplemented with chemicals at the following concentrations: 2,6-diaminopimelic acid, 0.3 mm; ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; gentamycin, 15 μg/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; and catalase on plates, 2000 units/ml.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Host for cloning | Laboratory stock |

| BL21 | Recombinant protein expression host strain | Novagen |

| WM3064 | ΔdapA, donor strain for conjugation | W. Metcalf, UIUCa |

| S. oneidensis | ||

| MR-1 | Wildtype | Laboratory stock |

| HG1070 | ΔkatB derived from MR-1 | Ref. 19 |

| HG1328 | ΔoxyR derived from MR-1 | Ref. 19 |

| HG-OxyRC203S | MR-1 carrying integrated Ptac-oxyRT613C | This study |

| HG-OxyRL197P | MR-1 carrying integrated Ptac-oxyRT607A | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHGE-Ptac | Kmr, IPTG-inducible expression vector | Ref. 35 |

| pHGEI01 | Kmr, integrative lacZ reporter vector | Ref. 28 |

| pBBR-Cre | Spr, helper plasmid for antibiotic cassette removal | Ref. 36 |

| pET-28a | Recombinant protein expression vector | Novagen |

| pHGE-Ptac-oxyR | Ptac-oxyR within pHGE-Ptac | This study |

| pHGE-Ptac-oxyRT613C | Ptac-oxyRT613C within pHGE-Ptac | This study |

| pHGE-Ptac-oxyRT607A | Ptac-oxyRT607A within pHGE-Ptac | This study |

| pHGEI01-PkatB-v | All PkatB variants-lacZ fusion within pHGEI01 | This study |

| pET-oxyR | oxyR within pET-28a | This study |

| pET-oxyRT613C | oxyRT613C within pET-28a | This study |

| pET-oxyRT607A | oxyRT607A within pET-28a | This study |

a University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Growth in liquid media was monitored by recording values of optical density at 600 nm (A600), as all strains used in this study were morphologically similar. Both LB and defined medium MS (18) were used for phenotypic assays in this study, and comparable results were obtained with respect to growth.

DNA manipulations

For inducible gene expression, the gene of interest was generated by PCR and introduced into the inducible plasmid pHGE-Ptac under the control of promoter Ptac (35). For OxyR, for example, the resulting vector, pHGE-Ptac-oxyR was verified by sequencing and transferred into the relevant strains via E. coli WM3064-mediated conjugation for chromosome integration as described before (28). To calibrate activities of Ptac integrated on the chromosome, Ptac was placed before the lacZ gene within integrative vector pHGEI01. The resulting vector, after verification by sequencing, was introduced into the S. oneidensis wildtype for chromosome integration. The same strategy was used to construct integrative lacZ reporter vectors carrying PkatB variants.

To construct S. oneidensis strains expressing OxyRC203S and OxyRL197P driven by IPTG-inducible Ptac, fragments of Ptac-oxyRT613C and Ptac-oxyRT607A were amplified from pHGE-Ptac-oxyRT613C and pHGE-Ptac-oxyRT607A, respectively, and cloned into pHGEI01. The resulting vector, after verification by sequencing, was introduced into the S. oneidensis wildtype for chromosome integration as described above.

Analysis of gene expression

The activity of target promoters was assessed using a single-copy integrative lacZ reporter system as described previously (28). Briefly, fragments of varying length (indicated in the relevant figures) containing the sequence upstream of the target operon were amplified, cloned into the reporter vector pHGEI01, and verified by sequencing. The resultant vector in E. coli WM3064 was then transferred by conjugation into relevant S. oneidensis strains, in which it integrated into the chromosome, and the antibiotic marker was removed subsequently (36). Cells grown to the mid-log phase under conditions specified in the text and/or figure legends were collected, and β-galactosidase activity was determined by monitoring color development at 420 nm using a Synergy 2 Pro200 Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (Tecan) presented as Miller units.

For qRT-PCR, S. oneidensis cells were grown in LB with the required additives to the mid-log phase and collected by centrifugation, and RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) as described before (37). RNA was quantified by using a NanoVue spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare). The analysis was carried out with an ABI7300 96-well qRT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems) as described previously (37). The expression of each gene was determined from three replicates in a single real-time qRT-PCR experiment. The cycle threshold (CT) values for each gene of interest were averaged and normalized against the CT value of the 16S rRNA gene, whose abundance is relatively constant during the log phase. The relative abundance of each gene is presented.

Droplet assays

Droplet assays were employed to evaluate viability and growth inhibition on plates. Cells grown in LB to the mid-log phase were collected by centrifugation and adjusted to 109 colony-forming units/ml, which was set as undiluted (dilution factor, 0). 10-Fold series dilutions were prepared with fresh LB medium. Five microliters of each dilution was dropped onto LB plates containing agents such as catalase and/or IPTG when necessary. The plates were incubated for 24 h or longer in the dark before being read. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Disc diffusion assays

Disc diffusion assays were done similarly to those done previously (19). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted into LB and grown to the mid-log phase (∼0.6 of A600). One hundred microliters of cultures was spread onto an agar plate containing required chemicals. Paper discs (diameter, 8 mm) containing 10 μl of 10 m H2O2 were placed on top of the agar. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 16 h before analysis. The diameters of the zones of clearing (zones of inhibition, in millimeters) generated by the peroxides were measured. All assays were done in triplicate using independent cultures, and the resulting zones of inhibition were averaged.

Analysis of catalase

To assess catalase levels, S. oneidensis cells grown in LB the mid-log phase were incubated with 0.2 mm H2O2 for 30 min and then collected by centrifugation and disrupted by French pressure cell treatment. Throughout this study, the protein concentration of the resulting cell lysates was determined using a Bradford assay with BSA as a standard (Bio-Rad). Aliquots of cell lysates containing the same amount of protein were subjected to 10% nondenaturing PAGE. Catalases were detected by using the corresponding activity-staining methods (38).

Activity of catalase was also assayed in a more quantitative approach, as described previously (19). Briefly, mid-log-phase cells in liquid medium were collected, washed twice in 50 mm KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.0), and resuspended in the same buffer and then disrupted by sonication. Ten microliters of cell extracts containing 40 ng/μl protein was added to 90 μl of KH2PO4 and 100 μl of 20 mm H2O2 in a 200-μl volume. Decomposition of H2O2 was measured at 240 nm with absorbance readings taken at 15-s time intervals for a total time of 3.5 min in a Tecan M200 Pro microplate reader. The unit of activity of each sample is expressed as μmol of H2O2 decomposed per min and per mg of protein (μmol·min−1·mg−1). Each sample was tested in quadruplicate for each strain assayed.

Site-directed mutagenesis

The coding sequence of S. oneidensis oxyR was amplified by PCR and cloned in pET28 for expressing recombinant proteins with an N-terminal His6 tag. The resulting pET28-oxyR, after sequence verification, was used as the template for site-directed mutagenesis to express OxyRC203S and OxyRL197P with a QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), as described previously (39). The resulting pET28-oxyRT607A and pET28-oxyRT613C was verified by sequencing.

Expression and purification of OxyR variants

Full-length S. oneidensis OxyRWT, OxyRC203S, and OxyRL197P were purified as His-tagged soluble proteins. E. coli BL21(DE3) strains carrying pET28-oxyR, pET28-oxyRT607A, or pET28-oxyRT613C grown in LB to the mid-log phase were induced with 0.2 mm IPTG at 25 °C for 6 h to produce high levels of His6-OxyR variants. His6-OxyR variants were purified from crude cell lysates by French pressure cell treatment over a nickel-ion affinity column (GE Healthcare). After removal of contaminant proteins with washing buffer containing 20 mm imidazole, the His-tagged OxyR variants were eluted in elution buffer containing 100 mm imidazole. The proteins were concentrated by ultrafiltration (10-kDa cutoff), exchanged into 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 150 mm NaCl, and further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 200 column (Pharmacia) run on an Äkta fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system (Pharmacia). The peak fractions were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250. Identification of purified proteins was confirmed with MS/MS analysis as described before (40).

Chemical cross-linking of OxyR

Chemical cross-linking with ethylene glycol bis-succinimidylsuccinate (Pierce) was used to examine the solution structure of OxyR. Cross-linking was initiated by the addition of EGS in dimethyl sulfoxide to a final concentration of 10 mm, with 2.5 μg of purified His6-OxyR in a total volume of 20 μl. The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min, quenched with 50 mm glycine, and analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE.

DNA binding analyses

To test interaction between OxyR and promoter regions of its target genes, EMSAs were conducted as described previously (41). DNA-binding assays and conditions were similar to those reported previously, although a fluorescent label was used in place of radioactivity to detect the promoter fragment. DNA probes covering the predicted OxyR binding sites were obtained by PCR, during which the double-stranded product was labeled with digoxigenin-ddUTP (Roche Diagnostics). The digoxigenin-labeled DNA probes were mixed with serial dilutions of purified OxyR of varying concentrations in binding buffer (4 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 40 mm NaCl, 4 mm MgCl2, 4% glycerol) containing 0.75 μg of poly(dI·dC) at room temperature for 15 min. The DNA/protein mixtures were loaded on 7% native polyacrylamide gels for electrophoretic separation, and the resulting gel was visualized with the UVP image system.

Fluorescence anisotropy was chosen as a method of DNA-binding analysis in equilibrium (42). DNA oligonucleotides 5′-end–labeled with 6-FAM were ordered from Sangon (Shanghai) and resuspended in annealing buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 0.05 mm EDTA). OxyR of increasing protein titrations was incubated with a solution containing 10 nm 6-FAM–labeled DNA, 100 nm competitive nonspecific DNA, 100 mg/liter BSA, 100 mm BisTris (pH 6.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 5% glycerol and added to a constant volume of 25 μl in a 384-well black assay plate (Costar). Fluorescence anisotropy of the fluorescein-labeled DNA was observed via excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm, using a plate reader (M200Pro, Tecan). Measurements were made in triplicate, and reported values are the averages for three separate triplicate runs. Data were plotted as average fluorescence anisotropy values as a function of protein concentration by using GraphPad Prism version 7. The Kd (dissociation constant) was calculated based on the equation generated by the best-fit curve using a single-ligand binding equation, r = ([P] × Δr)/(Kd + [P]), where r is the anisotropy value, Δr is the change in anisotropy, [P] is the concentration of added protein, and Kd is the dissociation constant of the protein with the DNA probe. Each OxyR variant was analyzed at each experiment by three individual replicates.

5′-RACE analysis of transcripts

The transcriptional start site of the katB gene of S. oneidensis was determined using a 5′-RACE kit (Invitrogen) as described recently (43). RNAs from S. oneidensis cells of the mid-log phase were extracted and quantified as described above. Reverse transcription was conducted on preprocessed RNAs without 5′-phosphates followed by two rounds of nested PCRs. The PCR products were subjected to agarose gel separation, with purification of the 5′-RACE products, and inserted into the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa) for direct DNA sequencing. The first DNA base adjacent to the 5′-RACE adaptor was regarded as the transcription start site.

DNase I footprinting

DNase I footprinting analysis was carried out as described elsewhere (44). DNA fragments of 152 bp with the predicted OxyR-binding site were generated by PCR using 6-FAM primers labeled at the 5′-end. Binding reactions for DNase I footprinting were conducted as for the EMSAs. The digested DNA was subjected to DNA sequencing and analyzed with Peak Scanner software (Applied Biosystems).

Other analyses

AlignACE (45) and MDScan (46) were used to identify OxyR-binding motifs in the putative promoter regions of genes. Sequence logos were generated using WebLogo (47). Student's t test was performed for pairwise comparisons with statistical significance set at the 0.05 confidence level. Values are presented as means ± S.E.

Author contributions

F.W. formal analysis; F.W. and L.K. investigation; F.W. writing-original draft; H.G. conceptualization; H.G. supervision; H.G. funding acquisition; H.G. project administration; H.G. writing-review and editing.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 41476105 and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province Grant LZ17C010001. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S3.

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- Ahp

- alkylhydroperoxide reductase

- LTTR

- LysR-type transcriptional regulator

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- RD

- regulatory domain

- IPTG

- isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- 6-FAM

- 6-carboxyfluorescein

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- LB

- lysogeny broth

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- bp

- base pair(s)

- EGS

- ethylene glycol bis(succinimidyl succinate)

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

References

- 1. Imlay J. A. (2013) The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 443–454 10.1038/nrmicro3032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Imlay J. A. (2015) Transcription factors that defend bacteria against reactive oxygen species. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 93–108 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mishra S., and Imlay J. (2012) Why do bacteria use so many enzymes to scavenge hydrogen peroxide? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 525, 145–160 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maddocks S. E., and Oyston P. C. F. (2008) Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154, 3609–3623 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Storz G., Tartaglia L. A., and Ames B. N. (1990) Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes: direct activation by oxidation. Science 248, 189–194 10.1126/science.2183352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zheng M., Aslund F, Storz G. (1998) Activation of the OxyR transcription factor by reversible disulfide bond formation. Science 279, 1718–1721 10.1126/science.279.5357.1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jo I., Kim D., Bang Y.-J., Ahn J., Choi S. H., and Ha N.-C. (2017) The hydrogen peroxide hypersensitivity of OxyR2 in Vibrio vulnificus depends on conformational constraints. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 7223–7232 10.1074/jbc.M116.743765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toledano M. B., Kullik I., Trinh F., Baird P. T., Schneider T. D., and Storz G. (1994) Redox-dependent shift of OxyR-DNA contacts along an extended DNA-binding site: a mechanism for differential promoter selection. Cell 78, 897–909 10.1016/S0092-8674(94)90702-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen H., Xu G., Zhao Y., Tian B., Lu H., Yu X., Xu Z., Ying N., Hu S., and Hua Y. (2008) A novel OxyR sensor and regulator of hydrogen peroxide stress with one cysteine residue in Deinococcus radiodurans. PLoS One 3, e1602 10.1371/journal.pone.0001602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loprasert S., Fuangthong M., Whangsuk W., Atichartpongkul S., and Mongkolsuk S. (2000) Molecular and physiological analysis of an OxyR-regulated ahpC promoter in Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 1504–1514 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tseng H.-J., McEwan A. G., Apicella M. A., and Jennings M. P. (2003) OxyR acts as a repressor of catalase expression in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 71, 550–556 10.1128/IAI.71.1.550-556.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seib K. L., Wu H.-J., Srikhanta Y. N., Edwards J. L., Falsetta M. L., Hamilton A. J., Maguire T. L., Grimmond S. M., Apicella M. A., McEwan A. G., and Jennings M. P. (2007) Characterization of the OxyR regulon of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 54–68 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ieva R., Roncarati D., Metruccio M. M. E., Seib K. L., Scarlato V., and Delany I. (2008) OxyR tightly regulates catalase expression in Neisseria meningitidis through both repression and activation mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1152–1165 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim J.-S., and Holmes R. K. (2012) Characterization of OxyR as a negative transcriptional regulator that represses catalase production in Corynebacterium diphtheria. PLoS One 7, e31709 10.1371/journal.pone.0031709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Teramoto H., Inui M., and Yukawa H. (2013) OxyR acts as a transcriptional repressor of hydrogen peroxide-inducible antioxidant genes in Corynebacterium glutamicum R. FEBS J. 280, 3298–3312 10.1111/febs.12312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Milse J., Petri K., Rückert C., and Kalinowski J. (2014) Transcriptional response of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 to hydrogen peroxide stress and characterization of the OxyR regulon. J. Biotechnol. 190, 40–54 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.07.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fredrickson J. K., Romine M. F., Beliaev A. S., Auchtung J. M., Driscoll M. E., Gardner T. S., Nealson K. H., Osterman A. L., Pinchuk G., Reed J. L., Rodionov D. A., Rodrigues J. L. M., Saffarini D. A., Serres M. H., Spormann A. M., Zhulin I. B., and Tiedje J. M. (2008) Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 592–603 10.1038/nrmicro1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi M., Wan F., Mao Y., and Gao H. (2015) Unraveling the mechanism for the viability deficiency of Shewanella oneidensis oxyR null mutant. J. Bacteriol. 197, 2179–2189 10.1128/JB.00154-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang Y., Dong Y., Luo Q., Li N., Wu G., and Gao H. (2014) Protection from oxidative stress relies mainly on derepression of OxyR-dependent katB and dps in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 196, 445–458 10.1128/JB.01077-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wan F., Shi M., and Gao H. (2017) Loss of OxyR reduces efficacy of oxygen respiration in Shewanella oneidensis. Sci. Rep. 7, 42609 10.1038/srep42609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christman M. F., Storz G., and Ames B. N. (1989) OxyR, a positive regulator of hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, is homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 3484–3488 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maciver I., and Hansen E. J. (1996) Lack of expression of the global regulator OxyR in Haemophilus influenzae has a profound effect on growth phenotype. Infect. Immun. 64, 4618–4629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li N., Luo Q., Jiang Y., Wu G., and Gao H. (2014) Managing oxidative stresses in Shewanella oneidensis: intertwined roles of the OxyR and OhrR regulons. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 1821–1834 10.1111/1462-2920.12418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi H., Kim S., Mukhopadhyay P., Cho S., Woo J., Storz G., and Ryu S. E. (2001) Structural basis of the redox switch in the OxyR transcription factor. Cell 105, 103–113 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00300-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Binnenkade L., Teichmann L., and Thormann K. M. (2014) Iron triggers λSo prophage induction and release of extracellular DNA in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 5304–5316 10.1128/AEM.01480-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shi M., Gao T., Ju L., Yao Y., and Gao H. (2014) Effects of FlrBC on flagellar biosynthesis of Shewanella oneidensis. Mol. Microbiol. 93, 1269–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gao T., Shi M., Ju L., and Gao H. (2015) Investigation into FlhFG reveals distinct features of FlhF in regulating flagellum polarity in Shewanella oneidensis. Mol. Microbiol. 98, 571–585 10.1111/mmi.13141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fu H., Jin M., Ju L., Mao Y., and Gao H. (2014) Evidence for function overlapping of CymA and the cytochrome bc1 complex in the Shewanella oneidensis nitrate and nitrite respiration. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 3181–3195 10.1111/1462-2920.12457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heyduk T., and Lee J. C. (1990) Application of fluorescence energy transfer and polarization to monitor Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein and lac promoter interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 1744–1748 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zheng M., Wang X., Doan B., Lewis K. A., Schneider T. D., and Storz G. (2001) Computation-directed identification of OxyR DNA binding sites in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4571–4579 10.1128/JB.183.15.4571-4579.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wei Q., Minh P. N., Dötsch A., Hildebrand F., Panmanee W., Elfarash A., Schulz S., Plaisance S., Charlier D., Hassett D., Häussler S., and Cornelis P. (2012) Global regulation of gene expression by OxyR in an important human opportunistic pathogen. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 4320–4333 10.1093/nar/gks017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Medina-Rivera A., Defrance M., Sand O., Herrmann C., Castro-Mondragon J. A., Delerce J., Jaeger S., Blanchet C., Vincens P., Caron C., Staines D. M., Contreras-Moreira B., Artufel M., Charbonnier-Khamvongsa L., Hernandez C., et al. (2015) RSAT 2015: Regulatory Sequence Analysis Tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W50–W56 10.1093/nar/gkv362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jo I., Chung I.-Y., Bae H.-W., Kim J.-S., Song S., Cho Y.-H., and Ha N.-C. (2015) Structural details of the OxyR peroxide-sensing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 6443–6448 10.1073/pnas.1424495112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schütz B., Seidel J., Sturm G., Einsle O., and Gescher J. (2011) Investigation of the electron transport chain to and the catalytic activity of the diheme cytochrome c peroxidase CcpA of Shewanella oneidensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6172–6180 10.1128/AEM.00606-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luo Q., Dong Y., Chen H., and Gao H. (2013) Mislocalization of Rieske protein PetA predominantly accounts for the aerobic growth defect of tat mutants in Shewanella oneidensis. PLoS One 8, e62064 10.1371/journal.pone.0062064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu H., Chen H., Wang J., Zhou G., Zhang H., Zhang L., and Gao H. (2013) Crp-dependent cytochrome bd oxidase confers nitrite resistance to Shewanella oneidensis. Environ Microbiol. 15, 2198–2212 10.1111/1462-2920.12091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yuan J., Wei B., Shi M., and Gao H. (2011) Functional assessment of EnvZ/OmpR two-component system in Shewanella oneidensis. PLoS One 6, e23701 10.1371/journal.pone.0023701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Clare D. A., Duong M. N., Darr D., Archibald F., and Fridovich I. (1984) Effects of molecular oxygen on detection of superoxide radical with nitroblue tetrazolium and on activity stains for catalase. Anal. Biochem. 140, 532–537 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90204-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun L., Dong Y., Shi M., Jin M., Zhou Q., Luo Z. Q., and Gao H. (2014) Two residues predominantly dictate functional difference in motility between Shewanella oneidensis flagellins FlaA and FlaB. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 14547–14559 10.1074/jbc.M114.552000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sun L., Jin M., Ding W., Yuan J., Kelly J., and Gao H. (2013) Posttranslational modification of flagellin FlaB in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 195, 2550–2561 10.1128/JB.00015-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gao H., Wang X., Yang Z. K., Palzkill T., and Zhou J. (2008) Probing regulon of ArcA in Shewanella oneidensis MR-I by integrated genomic analyses. BMC Genomics 9, 42 10.1186/1471-2164-9-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Edwards J. S., Betts L., Frazier M. L., Pollet R. M., Kwong S. M., Walton W. G., Ballentine W. K. 3rd, Huang J. J., Habibi S., Del Campo M., Meier J. L., Dervan P. B., Firth N., and Redinbo M. R. (2013) Molecular basis of antibiotic multiresistance transfer in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2804–2809 10.1073/pnas.1219701110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li M., Meng Q., Fu H., Luo Q., and Gao H. (2016) Suppression of fabB mutation by fabF1 is mediated by transcription read-through in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 198, 3060–3069 10.1128/JB.00463-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilson D. O., Johnson P., and McCord B. R. (2001) Nonradiochemical DNase I footprinting by capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 22, 1979–1986 10.1002/1522-2683(200106)22:10%3C1979::AID-ELPS1979%3E3.0.CO%3B2-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roth F. P., Hughes J. D., Estep P. W., and Church G. M. (1998) Finding DNA regulatory motifs within unaligned noncoding sequences clustered by whole-genome mRNA quantitation. Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 939–945 10.1038/nbt1098-939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu X. S., Brutlag D. L., and Liu J. S. (2002) An algorithm for finding protein–DNA binding sites with applications to chromatin-immunoprecipitation microarray experiments. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 835–839 10.1038/nbt717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., and Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.