Abstract

Background:

Endodontic infections require effective removal of microorganisms from the root canal system for long-term prognosis. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is the most effective irrigant currently, but potential complications due to its toxicity warrant search for newer alternatives. In this study, the antimicrobial efficacy of Morinda citrifolia (MC), green tea polyphenols and Triphala was compared with 5% NaOCl against Enterococcus faecalis.

Materials and Methods:

In this in vitro study sixty extracted human premolar teeth were infected with E. faecalis, a Group D Streptococci for 48 h. At the end of 48 h, the vital bacterial population was assessed by counting the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) on blood agar plate. Samples were divided into five groups; Group I (distilled water), Group II (NaOCl), Group III (MC), Group IV (Triphala), and Group V (green tea polyphenols). The samples were irrigated with individual test agents and CFUs were recorded. Kruskal–Wallis test was performed as the parametric test to compare different groups. Student's t-test was used to compare mean values between groups before and after treatment with test agents (P < 0.001).

Results:

NaOCl was the most effective irrigant the elimination of E. faecalis reinforcing its role as the best irrigant available currently and a gold standard for comparison of the experimental groups. Its antibacterial effect was comparable to Triphala. Among the experimental groups, MC showed the minimum antibacterial effect.

Conclusion:

The use of herbal alternatives as a root canal irrigant might prove to be advantageous considering the several undesirable characteristics of NaOCl.

Key Words: Enterococcus faecalis, green tea, Morinda citrifolia, sodium hypochlorite, Triphala

INTRODUCTION

Primary endodontic infections are caused by oral microorganisms, which are usually opportunistic pathogens that may invade a root canal containing necrotic tissue and establish an infectious process. Elimination of these microorganisms from root canal system is one of the main objectives of the root canal treatment.[1] However, microorganisms may remain after conventional canal preparation, either within the dentinal tubules or bound within the apical dentin plug.[2]

One of the main causes of root canal therapy failure is the persistence of microorganisms and their reinfection. Sundqvist et al. recovered numerous species of bacteria from failed root canal cases; of which Enterococcus faecalis was found to be the most prevalent bacteria.[3] Enterococci survive very harsh environments including extreme alkaline pH (9.6) and salt concentrations.[4] It can survive in well instrumented and obturated root canals alone with scanty available nutrients and has the ability to resist high pH because of its functioning proton pump which drives protons into the cell to acidify its cytoplasm.[5]

Cleaning of the root canal system using mechanical instrumentation alone is ineffective due to the extremely complex root canal anatomy.[6] Hence, cleaning and shaping should be accompanied by copious irrigation. The various irrigants used are sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), citric acid, chlorhexidine gluconate, hydrogen peroxide, povidone-iodine, etc.[7]

Scientific evidence relating to the desirable properties of an irrigant reveals that NaOCl is currently the irrigant of choice and is preferred by most clinicians. However, concerns as to its effect on vital tissues still persist. It causes severe inflammation and cellular destruction in all tissues, and when extrusion occurs through the apices of teeth, it causes severe pain, swelling, and necrosis.[8]

Due to constant increase in antibiotic-resistant strains and the side effects caused by synthetic drugs, there is the need for an alternative disinfecting measure. To overcome the disadvantages of currently known irrigants, use of herbal alternatives is suggested. The rationale of this study was to find less toxic alternatives to currently available irrigants. Herbal products tested in this study include Morinda citrifolia (MC) fruit extract, green tea polyphenols (GTPs), and Triphala.

MC, commercially known as noni, is considered as an important folk medicine. Its juice contains the antibacterial compounds L-asperuloside and alizarin. Its juice has a broad range of therapeutic effects and its use as an irrigant might be advantageous because it is a biocompatible antioxidant and not likely to cause severe injuries such as NaOCl accidents.[9]

Triphala is an ayurvedic herbal rasayana formula consisting of equal parts of three myrobalans, taken without seed: Amalaki (Emblica officinalis), Bibhitaki (Terminalia bellirica), and Haritaki (Terminalia chebula). Formulations of Triphala has been claimed to have antiviral and antibacterial effect, and the fruits that are rich in citric acid may aid in removal of smear layer.[10]

Green tea, the traditional drink of Japan and China, is prepared from the young shoots of the tea plant Camellia sinensis. Extracts of Japanese green tea may be useful as a medicament for the treatment of infected root canals.[11] Biocompatible irrigants are needed to promote dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) attachment to root canal dentin, which is essential to accomplish some regenerative endodontic therapies. Common endodontic irrigating solutions such as NaOCl and chlorhexidine are cytotoxic to pulp cells and oral tissues. Hence, more biocompatible irrigants are suggested for use in cases planned for regenerative endodontics. MC juice (MCJ) and EDTA have been proved to help maintain the survival and attachment of DPSCs to be used as part of regenerative endodontic treatment.[12] The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the antimicrobial efficacy of MC, GTPs, and Triphala, with 5% NaOCl against E. faecalis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In an in vitro study 60 freshly extracted human single rooted premolars with matured apices and standard strain of E. faecalis (ATCC 29212) were selected for the study. Irrigants used were commercially available 5% Sodium hypochlorite, distilled water, 17% EDTA, fresh Morindacitrifolia fruits from which extract was prepared, Green tea polyphenols (95% GTP, Herbal solutions, India) and Triphala extract (100%, Organic India Ltd). Microbiological media used were Mueller Hinton broth and Blood agar medium.

The preparation of Morindacitrifolia extract was done. Fresh fruits were chopped into pieces and dried at room temperature for 24 hrs. The air dried fruits were kept at 40°C in hot air oven for 24 hrs to remove moisture content and ground into powder form by using mortar and pestle and mixed in a ratio of 1:5 with solvent ethanol. The extraction was carried out in a shaker water bath at 40°C for 48 hrs. The extract was filtered through whatmann no: 1 filter paper, concentrated to dryness and dissolved in required concentration in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

The minimum inhibitory concentration of the different groups was determined by tube dilution method. The extracts in powder form were dissolved at a concentration of 64 mg/ml in 10% DMSO, and serial dilution was carried out to find the minimum inhibitory concentration. Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was also determined.

The MBC of NaOCl is 0.5%. The commonly used concentration for root canal irrigation is 5%. Hence, the concentrations of other irrigants were also adjusted accordingly. The solutions were prepared at a concentration of 10 times their MBC.

For sample preparation, the selected teeth were decoronated at the cementoenamel junction using a diamond disc, to obtain approximately 13 mm length of root samples and pulpal remnants were extirpated. The apices of teeth were sealed with glass ionomer cement (Fuji IX, GC, Tokyo, Japan). The remaining root surface was coated with a double layer of nail varnish to isolate the internal root environment. Coronal flaring was done using Gates Glidden Drills (size 1–4), and apical preparation was done till ISO size 50 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland). Copious irrigation was done with 5% NaOCl, followed by 17% EDTA for 5 min each. Finally, canals were rinsed with 5 ml of normal saline and stored in distilled water until use.

The sixty samples were divided into five groups of 12 teeth each. The five Micro Tip boxes containing sixty samples were sterilized at 121° C for 15 min at 15 psi pressure in an autoclave. Assurance of negativity was confirmed by culture testing. The bacteria suspension was then inoculated, and the samples were incubated aerobically at 37°C in a biochemical oxygen demand (B O D) incubator for 48 h. After inoculation, the washable content of each root canal was removed with sterile saline.

Sampling of the attached bacteria was done by resuspending the bacteria in the sterile saline. A standard bacteriological loop (0.001 ml or 1 μl) was dipped inside the root canal containing the saline and streaked onto the blood agar plate and incubated for 2 days at 37°C in a B O D incubator. After incubation, the colony-forming unit (CFU) counts for all teeth were recorded using colony counter.

The teeth will be randomly divided into five groups of 12 teeth each: Group I (distilled water), Group II (NaOCl), Group III (MC), Group IV (Triphala), and Group V (GTPs). The teeth in different groups were irrigated with the corresponding test solutions. After incubation, the CFU counts for all teeth were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was used to compare mean values between before and after treatment groups. Kruskal–Wallis test was performed as the parametric test to compare different groups. For all statistical evaluations, a two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

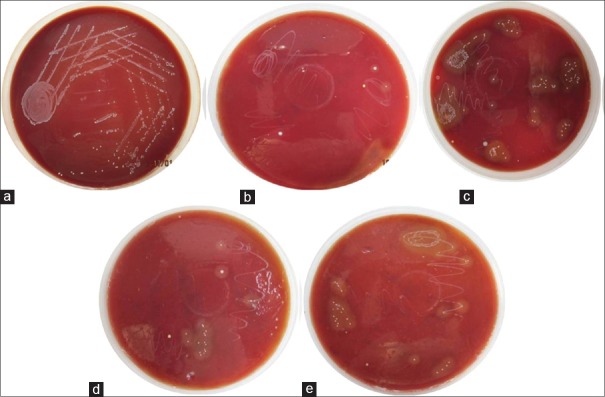

When bacterial colony counts were done for the teeth samples after inoculation of E. faecalis, the counts varied from 825 to 1119 CFU/μl. After the test application of each agent, the CFU counts of different groups were an average of Group I: 944.50 CFUs/μl, Group II: <1 CFUs/μl, Group III: 158.17 CFUs/μl, Group IV: 15.92 CFUs/μl, and Group V: 56.67 CFUs/μl [Figure 1a–e].

Figure 1.

(a) Distilled water, (b) sodium hypochlorite, (c) Morinda citrifolia, (d) triphala, (e) green tea polyphenols.

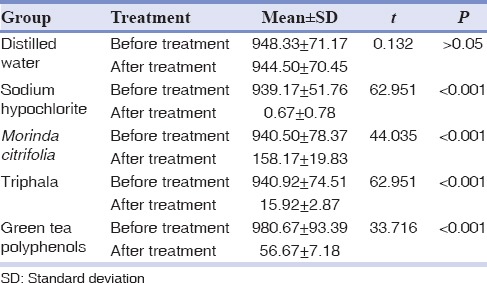

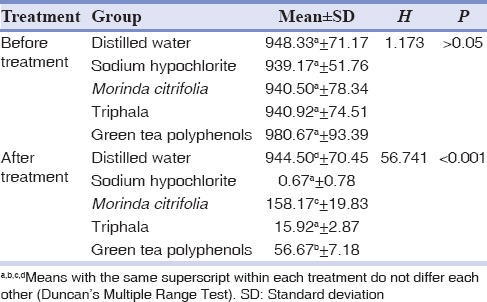

Bacterial CFU counts for all the experimental groups obtained after application of test agents were compared with the values attained before application and were found to be statistically significant except for the distilled water group. When the individual groups were compared before treatment, there was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between them. After test with individual irrigating agents, there was statistically significant difference (P< 0.001) between the groups. Group II (NaOCl) and Group IV (Triphala) showed no statistically significant difference after treatment; whereas the result was statistically significant when Group II (NaOCl) and Group IV (Triphala) were compared with Group I (distilled water), Group III (MC) and Group V (GTPs) after treatment [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Comparison of mean colony forming unit between test and control in different groups

Table 2.

Kruskal-Wallis test comparing different groups before and after treatment

DISCUSSION

The successful culmination of endodontic therapy lies in delivering efficacious treatment to the patient, which renders complete resolution of pulpal or periapical pathosis. E. faecalis is is a nonspore-forming, fermentative facultative anaerobic Gram-positive coccus that belongs to the Group D streptococci.[13] Studies investigated its occurrence in root-filled teeth with periradicular lesions and demonstrated a prevalence ranging from 24% to 77%.[14] E. faecalis was found in cases of failed endodontic therapy (67%) than in primary endodontic infections (18%).[15] The pathogenicity is believed to be associated with its ability to produce cytolysin, a toxin that causes rupture of a variety of target membranes including bacterial cells, erythrocytes, and other mammalian cells. It is commonly found in a high percentage of root canal failures, and it is able to survive in the root canal as a single organism or as a major component of the flora.[16] Both culture and PCR methods are sensitive to detect E. faecalis in root canals.[17] Considering the nature of the organism and its capability to populate and survive in unsuccessful cases of therapy, this organism assumes importance and is an imperative choice for this study.

NaOCl is the universally accepted irrigant of choice. However, inadvertent injection beyond the root apex can cause violent tissue reactions such as acute inflammation followed by necrosis.[18] Hypochlorite preparations are sporicidal ad virucidal and show far greater tissue dissolving effects on necrotic than on vital tissues.[19,20] To avoid extrusion, it is always prudent to confirm the length and integrity of the root canal system before irrigating with concentrated solutions.[21] Concentration as low as 1:1000 (v/v) NaOCl in saline caused complete hemolysis of red blood cells in vitro.[22]

MC, the ''noni'' is considered as a panacea because of the profound claim on its medicinal uses in treating many diseases of microbial origin. Noni fruit contains numerous iridoids, and main compounds include asperuloside, asperulosidic acid, and deacetylasperulosidic acid.[23] The main organic acids are capric and caprylic acids, whereas the principal alkaloid is xeronine.in vitro research shown that noni has antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and cardiovascular activity.[24]

Studies indicate that 6% MCJ in combination with EDTA can remove the smear layer from the walls of instrumented root canals.[25] A study suggested that biocompatible irrigants are needed to promote DPSC attachment to root canal dentin, which is essential for regenerative endodontic therapies.[7] It has antimicrobial action against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus morganii, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, E. faecalis, and Candida albicans.[26] Another study suggested that propolis and MCJ were effective against E. faecalis in dentin of extracted teeth.[27] MC fruit extract had an antifungal effect on C. albicans and the inhibitory effect varied with concentration and contact time.[28]

Green tea is prepared from unfermented leaves and is a rich source of polyphenols, particularly flavonoids such as the catechins, catechingallates, and proanthocyanidins.[29] Many of the physiological activities reported for tea extracts have been found to be due to the polyphenol moiety.[30] The fresh leaves contain caffeine, theobromine, theophylline, and other methylxanthines such as lignin, organic acids, chlorophyll, and free amino acids.[31] Many of the biological properties of green tea have been ascribed to the catechin fraction, which constitutes up to 30% of the dry leaf weight.[32] In a study, Triphala, GTPs, and mixture of Doxycycline, citric acid and a detergent (MTAD) showed statistically significant antibacterial activity against E. faecalis biofilm formed on tooth substrate.[33]

Triphala is a combination of three tropical fruits' preparation comprised of equal parts of T. chebula, E. officinalis, and T. bellirica which possess anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antiaging properties. A study evaluated the antimicrobial efficacy of Triphala, GTPs, and 3% of NaOCl against E. faecalis biofilm formed on tooth substrate and concluded that NaOCl had maximum antibacterial activity against E. faecalis biofilm formed on tooth substrate. Triphala and GTP also showed significantly better antibacterial activity.[34]

The in vitro model used in this study was adapted from the one used by Haapasalo and Orstavik.[35] Apical preparation was standardized to number 50 K-file (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) and step-back preparation was done. The apical preparation with number. 50 K-file aided in better irrigant penetration and biomechanical preparation standardized the internal diameter of the root canals.[36] The root canals of all tooth samples were irrigated with different test agents for 5 min followed by saline as a final irrigant, to eliminate prolonged contact time of each irrigant and to standardize the groups. Therefore, the potential carryover of antibacterial activity to the culture medium was also avoided. DMSO was used as a solvent for MC fruit extract, Triphala, and GTP which is a clean, safe, highly polar, aprotic solvent that helps in bringing out the pure properties of all the components of the herb being dissolved.[37]

Group II (NaOCl) was the most effective in elimination of E. faecalis. Its antibacterial effect was comparable to that of Group IV (Triphala). Group V (GTPs) and Group III (MC) also showed a significant antibacterial effect. Among the test agents, Group III (MC) showed the minimum antibacterial effect. Triphala showed more potency on E. faecalis biofilm. This may be attributed to its formulation, which contains three different medicinal plants in equal proportions. Tannic acid represents the major constituent of the ripe fruit of T. chebula, T. belerica, and E. officinalis. Earlier studies reported that tannic acid is bacteriostatic and bactericidal to some Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens.[38] In this study, Triphala showed antibacterial activity comparable to that of NaOCl which is a gold standard for comparison of root canal irrigants.

CONCLUSION

Triphala, GTPs, and MC showed a significant antibacterial effect against E. faecalis. Among the tested agents, Triphala was found to be as efficacious as NaOCl. Herbal alternatives might prove to be advantageous considering the several undesirable properties of NaOCl. However, the preparation of fresh irrigating solutions, standardization, and toxicity should be further evaluated before they are recommended for clinical use.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest, real or perceived, financial or non-financial in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iqbal A. Antimicrobial irrigants in the endodontic therapy. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2012;6:186–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Nazhan S, Al-Sulaiman A, Al-Rasheed F, Alnajjar F, Al-Abdulwahab B, Al-Badah A, et al. Microorganism penetration in dentinal tubules of instrumented and retreated root canal walls.in vitro SEM study. Restor Dent Endod. 2014;39:258–64. doi: 10.5395/rde.2014.39.4.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundqvist G, Figdor D, Persson S, Sjögren U. Microbiologic analysis of teeth with failed endodontic treatment and the outcome of conservative re-treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tendolkar PM, Baghdayan AS, Shankar N. Pathogenic enterococci: New developments in the 21st century. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2622–36. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans M, Davies JK, Sundqvist G, Figdor D. Mechanisms involved in the resistance of Enterococcus faecalis to calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 2002;35:221–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger Z, Solomonov M, Kfir A. The role of mechanical instrumentation in the cleaning of root canals. Endod Topics. 2013;29:87–109. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryce G, O'Donnell D, Ready D, Ng YL, Pratten J, Gulabivala K, et al. Contemporary root canal irrigants are able to disrupt and eradicate single-and dual-species biofilms. J Endod. 2009;35:1243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Sebaei MO, Halabi OA, El-Hakim IE. Sodium hypochlorite accident resulting in life-threatening airway obstruction during root canal treatment: A case report. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2015;7:41–4. doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S79436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assi RA, Darwis Y, Abdulbaqi IM, Khan AA, Vuanghao L, Laghari MH. Morinda citrifolia (Noni): A comprehensive review on its industrial uses, pharmacological activities, and clinical trials. Arabian J Chem. 2015;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhavikatti SK, Dhamija R, Prabhuji ML. Triphala: Envisioning its role in dentistry. Int Res J Pharm. 2015;6:309–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horiba N, Maekawa Y, Ito M, Matsumoto T, Nakamura H. A pilot study of Japanese green tea as a medicament: Antibacterial and bactericidal effects. J Endod. 1991;17:122–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)81743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ring KC, Murray PE, Namerow KN, Kuttler S, Garcia-Godoy F. The comparison of the effect of endodontic irrigation on cell adherence to root canal dentin. J Endod. 2008;34:1474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rôças IN, Siqueira JF, Jr, Santos KR. Association of Enterococcus faecalis with different forms of periradicular diseases. J Endod. 2004;30:315–20. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siqueira JF, Jr, Rôças IN. Exploiting molecular methods to explore endodontic infections: Part 2 – Redefining the endodontic microbiota. J Endod. 2005;31:488–98. doi: 10.1097/01.don.0000157990.86638.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rôças IN, Siqueira JF, Jr, Aboim MC, Rosado AS. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of bacterial communities associated with failed endodontic treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cogulu D, Uzel A, Oncag O, Aksoy SC, Eronat C. Detection of Enterococcus faecalis in necrotic teeth root canals by culture and polymerase chain reaction methods. Eur J Dent. 2007;1:216–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleier DJ, Averbach RE, Mehdipour O. The sodium hypochlorite accident: Experience of diplomates of the American board of endodontics. J Endod. 2008;34:1346–50. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonnell G, Russell AD. Antiseptics and disinfectants: Activity, action, and resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:147–79. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin JH, Taylor HD. Behavior of hypochlorite and of chloramine-T solutions in contact with necrotic and normal tissues in vivo. J Exp Med. 1918;27:627–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.27.5.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gernhardt CR, Eppendorf K, Kozlowski A, Brandt M. Toxicity of concentrated sodium hypochlorite used as an endodontic irrigant. Int Endod J. 2004;37:272–80. doi: 10.1111/j.0143-2885.2004.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pashley EL, Birdsong NL, Bowman K, Pashley DH. Cytotoxic effects of NaOCl on vital tissue. J Endod. 1985;11:525–8. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(85)80197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potterat O, Hamburger M. Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit – Phytochemistry, pharmacology, safety. Planta Med. 2007;73:191–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-967115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan-Blanco Y, Vaillant F, Perez AM, Reynes M, Brillouet JM, Brat P. The noni fruit (Morindacitrifolia L.): A review of agricultural research, nutritional and therapeutic properties. J Food Compost Anal. 2006;19:645–54. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray PE, Farber RM, Namerow KN, Kuttler S, Garcia-Godoy F. Evaluation of Morinda citrifolia as an endodontic irrigant. J Endod. 2008;34:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyagi SP, Sinha DJ, Garg P, Singh UP, Mishra CC, Nagpal R, et al. Comparison of antimicrobial efficacy of propolis, Morinda citrifolia, Azadirachta indica (Neem) and 5% sodium hypochlorite on Candida albicans biofilm formed on tooth substrate: An in-vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:532–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.120973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kandaswamy D, Venkateshbabu N, Gogulnath D, Kindo AJ. Dentinal tubule disinfection with 2% chlorhexidine gel, propolis, Morinda citrifolia juice, 2% povidone iodine, and calcium hydroxide. Int Endod J. 2010;43:419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jainkittivong A, Butsarakamruha T, Langlais RP. Antifungal activity of Morinda citrifolia fruit extract against Candida albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:394–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor PW, Hamilton-Miller JM, Stapleton PD. Antimicrobial properties of green tea catechins. Food Sci Technol Bull. 2005;2:71–81. doi: 10.1616/1476-2137.14184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stagg GV, Millin DJ. The nutritional and therapeutic value of tea-A review. J Sci Food Agric. 1975;26:1439–59. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham HN. Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev Med. 1992;21:334–50. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hara Y. Green Tea: Health Benefits and Applications. New York, USA: Marcel Dekker; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prabhakar J, Senthilkumar M, Priya MS, Mahalakshmi K, Sehgal PK, Sukumaran VG, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of herbal alternatives (Triphala and green tea polyphenols), MTAD, and 5% sodium hypochlorite against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formed on tooth substrate: An in vitro study. J Endod. 2010;36:83–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pujar M, Patil C, Kadam A. Comparison of antimicrobial efficacy of Triphala, Green tea polyphenols and 3% of sodium hypochlorite on Enterococcus faecalis biofilms formed on tooth substrate:in vitro. J Int Oral Health. 2011;3:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haapasalo M, Orstavik D. in vitro infection and disinfection of dentinal tubules. J Dent Res. 1987;66:1375–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660081801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ram Z. Effectiveness of root canal irrigation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:306–12. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de la Torre JC. Biological actions and medical applications of dimethyl sulfoxide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1983;411:1–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jagadish L, Anand Kumar VK, Kaviyarasan V. Effect of Triphala on dental bio-film. Indian J Sci Tech. 2009;2:30–3. [Google Scholar]