Abstract

The most common cause of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease. The etiology of the disease is unknown, although considerable evidence suggests a critical role for the soluble oligomers of amyloid beta peptide (Aβ). Because Aβ increases the expression of purinergic receptors (P2XRs) in vitro and in vivo, we studied the functional correlation between long-term exposure to Aβ and the ability of P2XRs to modulate network synaptic tone. We used electrophysiological recordings and Ca2+ microfluorimetry to assess the effects of chronic exposure (24 h) to Aβ oligomers (0.5 μM) together with known inhibitors of P2XRs, such as PPADS and apyrase on synaptic function. Changes in the expression of P2XR were quantified using RT-qPCR. We observed changes in the expression of P2X1R, P2X7R and an increase in P2X2R; and also in protein levels in PC12 cells (143%) and hippocampal neurons (120%) with Aβ. In parallel, the reduction on the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs (72% and 35%, respectively) were prevented by P2XR inhibition using a low PPADS concentration. Additionally, the current amplitude and intracellular Ca2+ signals evoked by extracellular ATP were increased (70% and 75%, respectively), suggesting an over activation of purinergic neurotransmission in cells pre-treated with Aβ. Taken together, our findings suggest that Aβ disrupts the main components of synaptic transmission at both pre- and post-synaptic sites, and induces changes in the expression of key P2XRs, especially P2X2R; changing the neuro-modulator function of the purinergic tone that could involve the P2X2R as a key factor for cytotoxic mechanisms. These results identify novel targets for the treatment of dementia and other diseases characterized by increased purinergic transmission.

Keywords: P2X receptor, Alzheimer’s disease, Amyloid-β peptide, Synaptic failure, ATP

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is responsible for ~70% of the 46.8 million cases of dementia worldwide (Prince et al., 2015), a number that is growing at a faster rate than predicted just 10 years ago (Ferri et al., 2005). The disease presents a significant burden on society, already costing almost 818 billion US dollars in palliative care (Prince et al., 2015). Therefore, it is imperative to develop innovative approaches and new strategies to treat or prevent the pathology.

Current dogma suggests that small, soluble oligomers of Aβ (SO-Aβ, ranging between 20 and 60 kDa) are responsible for the toxic effects (Lesné et al., 2006). However, how SO-Aβ induce toxicity is unknown. One hypothesis is that the oligomers interact with or bind to synaptic proteins (NMDAR, PrPC, and Frizzled) in a manner that alters normal synaptic function (Decker et al., 2010; Ferreira et al., 2012; Lauren et al., 2009; Peters et al., 2015). It is also suggested that SO-Aβ form non-selective pores in the plasma membrane (Arispe et al., 1993, 2007; Lal et al., 2007). In support of this hypothesis, it was found that SO-Aβ perforate neuronal membranes by forming a pore that is large enough to conduct molecules with molecular weights as high as 900 Da (Sepúlveda et al., 2014). In cell cultures treated with SO-Aβ, is has been observed that ATP increased on extracellular media, suggesting that SO-Aβ pore lead the flux of ATP through it, and this intracellular ATP leakage enhance it extracellular concentration (Kim et al., 2012; Orellana et al., 2011; Sáez-Orellana et al., 2016). The downstream sequel of ATP release involves activation of metabotropic P2Y and ionotropic P2X receptors. It was shown that P2X7Rs can be overexpressed in the brains of AD patients assayed post-mortem and in microglia from Aβ-treated rats (McLarnon et al., 2006), and activate non-amyloidogenic processing of APP (Amyloid Precursor Protein) (Darmellah et al., 2012; Delarasse et al., 2011). Thus, it is entirely possible that eATP contributes to neuroinflammation in AD patients (Di Virgilio et al., 2009) by gating P2X7Rs and activating microglia (Choi et al., 2007; Madry and Attwell, 2015; Parvathenani et al., 2003).

P2XRs are also expressed in neuronal cells in the CNS, and activation of P2X4Rs in animal models contributes to the formation of LTP (Long Term Potentiation) in the hippocampus (Baxter et al., 2011; Tsuda et al., 2013). P2X4Rs possess a non-canonical domain that mediates internalization upon activation as a mechanism to limit Ca2+ flux (Royle et al., 2002, 2005). Interestingly, SO-Aβ induces proteolytic cleavage of this non-canonical internalization domain, thereby prolonging the presence of P2X4Rs in the plasma membrane and facilitating the toxic effects of SO-Aβ mediated by eATP-gated Ca2+ overload (Varma et al., 2009).

Recently, we demonstrated that acute exposure of neurons to SO-Aβ increases eATP, leading to an elevation in the [Ca2+]i and enhancement of synaptic activity through P2XRs (Sáez-Orellana et al., 2016). In the present paper, we evaluate the contribution of purinergic transmission to chronic SO-Aβ-induced neuronal damage, and measure the changes in P2XR protein expression of cultured hippocampal neurons in response to incubation with SO-Aβ. Our data demonstrates for the first time that the P2X2 purinergic receptor is involved in the toxic physiopathology of soluble oligomers of the beta amyloid peptide.

2. Methods

In the present work, we used two neuronal primary cell cultures (hippocampal and cortical) and one cell line culture with neuronal lineage (PC12).

2.1. Primary hippocampal cultures

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were handled in accordance with ethical regulations established by NIH and the University of Concepción. Primary cultures of embryonic hippocampus or cortex of 18–19 days were prepared and maintained using previously published protocols (Fuentealba et al., 2012). All experiments were performed in cultures having 10–12 days in vitro.

2.2. Primary cortical cultures

Cortices from the same embryos used for hippocampal cultures were collected and trypsinized to isolate the cells and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, the cell pellet was washed twice with ice cold DPBS to dilute the trypsin. The cells were counted and plated using plating media (MEM supplemented with 10% horse serum, 4 μg/ml DNase and 2 mM L-Glutamine, all reagents from HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA). Plating media was replaced after 24 h with feeding media (MEM supplemented with 5% horse serum, 5% fetal bovine serum; HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA), and 0.5% N3 (a mixture of defined nutrients). Feeding media was changed every 3 days with fresh feeding media. Neurons were used between 10 and 12 days in vitro.

2.3. PC12 cells

PC12 cells from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM with 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. The cells were incubated under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2) and when 80% confluence was achieved, the cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin for 10 min, washed and resuspended in HyQ DMEM/High-Glucose (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) with 5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco). The cells were then plated at a concentration of 50,000 cells/well for experiments and used 24 h after plating under experimental conditions similar for neurons.

2.4. Aβ peptide

Stock peptide (rPeptide, Bogart, GA, USA) was reconstituted in DMSO to a concentration of 2.3 mM and stored at −20 °C. Subsequently, the peptide was aggregated in sterile H2O at 80 μM using a standardized protocol (800 rpm, 37 °C, 2 h). All treatments with Aβ were made at a final concentration of 0.5 μM in Krebs-Hepes (pH 7.4) and maintained for 24 h, unless otherwise indicated.

2.5. Cell viability

We used the in vitro MTT assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) to evaluate changes in cell viability by measuring the ability of mitochondria to reduce 3-[4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT salt) to formazan. Hippocampal cells were subjected to different experimental conditions, and then incubated for 30 min in MTT (1 mg/ml). The insoluble formazan was solubilized in 100 μl of 2-propanol, and the absorbance was read in a NOVOstar multiplate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany).

2.6. Electrophysiology

The whole-cell patch clamp technique was used as previously reported (Fuentealba et al., 2011, 2012) using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA) in voltage clamp mode (holding potential −60 mV). Miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSC) were pharmacologically isolated using appropriate concentrations of TTX (50 nM), bicuculline (5 μM), D-AP5 (50 μM), and/or CNQX (5 μM). Neurons were pre-incubated for 24 h with Aβ (0.5 μM), PPADS (10 μM), apyrase (3U/ml), and DPCPX (1 μM). The pipette solution was (in mM): 120 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 ATP, 0.5 GTP, 10 BAPTA (pH 7.4, 300 mOsm). The bath solution contained (in mM): 150 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2 CaCl2 2,1 MgCl2; 10 HEPES,10 Glucose (pH 7.4, 320 mOsm). Analysis was performed offline using Clampfit 10 (Axon Instruments, USA).

2.7. Ca2+ measurements

Hippocampal cultures were loaded with the non-ratiometric Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent probe Fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 20 min in PBS using standard incubation conditions. Subsequently, the cells were washed 20 min with PBS and finally washed 3 times with normal external solution and then mounted on an inverted microscope. Changes in fluorescence (ex 480 nm, em 520 nm, 200 ms exposure) were acquired every 1 s for 10 min using an iXon + EMCCD camera (Andor, Ireland) and the Imaging Workbench 6.0 software (Indec Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

2.8. RT-qPCR

Total RNA extraction was performed using Rneasy© Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to manufacturer instructions. RNA purity and quantification was assessed using absorbance readings at 260/280 nm. RNA integrity was assayed by 1% agarose gel. Reverse transcription was performed using the AffinityScript© QPCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to manufacturer instructions. Total cDNA was analyzed by qPCR using Brilliant II SYBR© Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a Stratagene MX3005P real time thermocycler. Specific primers for each rat P2X subunit were designed and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA) and are listed on Table 1. Quantification was performed by the Pfaffl method using GAPDH and β-actin as reference genes (Pfaffl, 2001). In brief, this method uses reference genes to compare the changes in expression in a gene of interest, comparing the treated (SO-Aβ) with untreated experimental condition according to the following equation:

Table 1.

Primer List for P2XRs and house keeping genes.

| mRNA | Accesion N° | Forward | Reverse | Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | NM_031144.2 | TTGCTGACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGA | ACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATCT | 159 |

| GAPDH | NM_017008.3 | ACAAGATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGA | AGCTTCCCATTCTCAGCCTTGACT | 199 |

| P2X1 | NM_012997.2 | AAGATCCCAAGCCCTGCTCTTCTT | TGTTGACCTTGAAGCGTGGAAAGC | 91 |

| P2X2 | NM_053656.2 | TGGACAGGCAGGGAAATTCAGTCT | TGGAGTACGCACCTTGTCGAACTT | 163 |

| P2X3 | NM_031075.1 | AGGAAAGAAGCAGGTTGAGAGGCT | TCTGTAAATTGAGGCCAGCCAGGA | 132 |

| P2X4 | NM_031594.1 | ACAAGAATCCTCCTGCTTCTGCCT | ATAGGGTGGAAGAACGTCTTGCGT | 159 |

| P2X5 | NM_080780.2 | AGATTCGATGATTGGGCCAGGACA | ACCAGGAGACCTTCCGTGAAACAA | 162 |

| P2X6 | NM_012721.2 | AAGAAGGGCAAGGACAGGCTACAT | TGACTGTTGCTTTCACCCTAGCCT | 146 |

| P2X7 | NM_019256.1 | ACACAGTCTGACGCCTCATTGCTA | TCAGTCCAGGACGTTAAAGGCACA | 99 |

In this equation E stands for the efficiency of the primer used, and ΔCt is the difference between the Ct observed in the untreated sample minus the Ct of the treated sample. The efficiency of the primers is measured as described by Pfaffl (2001). Statistical differences in expression where assessed using an inference method based in a one sample t-test, assuming an expected value of 1 if there was no change in expression. The significance of the discrepancy was indicated in the graphs.

2.9. Western blot

Protein from control and Aβ-treated (0.5 μM, 24 h) culture lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (250 mA, 100 min) that were subsequently blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS-T. The primary antibodies used were anti-PSD95 (Mouse monoclonal, 1:1000, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), anti-P2X2 and anti P2X7 (polyclonal, 1:1000, Alomone Labs, Israel) and anti-β-actin (mouse monoclonal, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies were used at 1:5000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Immunoreactive bands were exposed using Clarity™ Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and quantified using an Odyssey FC detection system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA).

2.10. Immunofluorescence

Cell cultures were treated and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4 °C, after which the cells were permeabilized and blocked with 10% horse serum plus 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. The samples were incubated with the following primary antibodies specific for: synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2, 1:400; mouse monoclonal, Synaptic Systems, Gottingen, Germany) used as specific presynaptic marker; Post Synaptic Density protein 95 (PSD95, 1:400, mouse monoclonal, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) used as specific postsynaptic marker; P2X2 and P2X7 (1:400, rabbit polyclonal, Alomone Labs, Israel) or Microtubule Associated Protein 2 (MAP2, 1:400; goat polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) used to identify the neurons on co-culture with glia, was used for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies: anti-Mouse IgG (1:200, Donkey, Cy3, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), anti-goat (1:200, Donkey, Alexa Fluor 488, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), or anti-Rabbit IgG (1:200, Donkey, Alexa Fluor 405, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 45 min. The slides were mounted using immunofluorescence mounting media (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Images were acquired using a LSM780 NLO confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany). Image processing and quantification was performed using Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.11. Drugs

Pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS, Tocris, Bristol, UK) was used at 10 μM because this concentration ensures the inhibition of P2XR and avoids the blockage of other receptors like P2Y. PPADS is the best pharmacological tool available to inhibit P2XR and is widely used for this objective. ATP (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), 8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX, Tocris, Bristol, UK), Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, Tocris, Bristol, UK), apyrase 30U/ml (EC 3.6.1.5, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA).

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data is presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test. For the electrophysiological current amplitude analysis we used Kolmogorov-Smirnov to evaluate differences in population distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.13. Ethical approbation

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethic and Scientific Committee at the University of Concepcion.

3. Results

3.1. P2XR blockade prevents the synaptic silencing induced by SO-Aβ

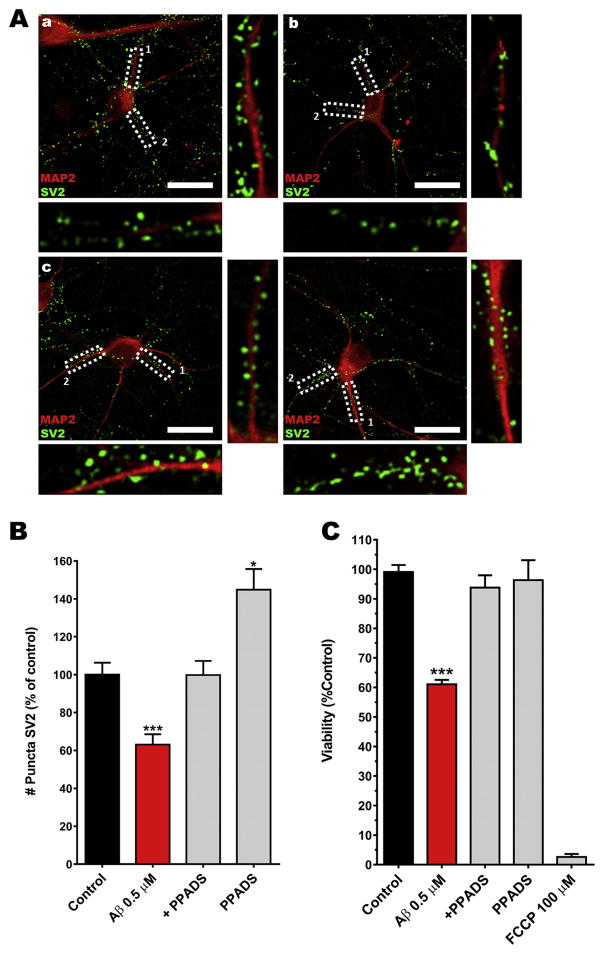

As previously reported, neurons chronically exposed (24 h) to SO-Aβ exhibited synaptic failure resulting from depletion of synaptic vesicles (Parodi et al., 2010) which was associated with the silencing of neuronal networks and neuronal death (Fuentealba et al., 2011, 2012). The cytotoxic events associated to SO-Aβ has been associated with ATP leakage from the neuron (Sáez-Orellana et al., 2016) and opens the possibility that this ATP can modulate synaptic function and neuronal survival through their purinergic receptors (activation and/or overexpression). To examine this possibility, we decided to test the synaptic function and neuronal connectivity by evaluating the integrity of synaptic components (pre- and post-) in neurons treated chronically with SO-Aβ (0.5 μM, 24 h); SV2 immunostaining was evaluated on control conditions (Fig. 1Aa), while oligomers have been shown to decrease it (63%), indicating neuronal network disconnection (Fig. 1Ab). This toxic effect was prevented (88%) by co-incubation with PPADS (10 μM, Fig. 1Ac), an antagonist classically used at this concentration to inhibit P2XR (Allgaier et al., 2004; Lalo et al., 2008; Laube, 2002). This result suggests that P2XR (probably activated by ATP leakage) contributed to SO-Aβ toxicity. The incubation with PPADS alone (Fig. 1Ad) showed a significant increment in SV2 immunostaining versus control condition (145%, Fig. 1B). This surprising result can be explained by a blockade of P2XR in control neurons (without SO-Aβ). All these effects on a synaptic marker were correlated with the viability of cortical primary cultures (12 days in vitro) under the same experimental conditions, where we found that SO-Aβ decreased cell viability to 61% of control values (Fig. 1C), while co-incubation with PPADS prevented chronic SO-Aβ toxicity; showing a 96% cell viability. Furthermore, PPADS alone did not show any effect on viability, whereas the positive control FCCP (100 μM) induced almost complete neuronal death (only 3% cell viability). Taken together, these results suggest that P2XR blockade could reduce the impact of amyloid β peptide on cell viability and neuronal network connectivity.

Fig. 1.

P2XR inhibition prevents neuronal death and SV2 reduction. Aa) Representative image of a hippocampal neuron (12 DIV, control). Ab) SO-Aβ treated neuron. Ac) SO-Aβ + PPADS treated neuron. Ad) PPADS (10 μM) treated neuron. In all images MAP2 is in red, SV2 in green, scale bar 20 μm. B) Quantification of immunoreactive puncta of SV2 in the same conditions as in panel A, control: 100 ± 6.3%; Aβ: 63 ± 5.5%; Aβ+PPADS: 88 ± 8%; PPADS: 145 ± 11%. *P < 0.05 vs. control, ***P < 0.001 vs. control, n = 5. C) Cortical primary cultures (12 DIV) were incubated with SO-Aβ 0.5 μM for 24 h in the absence or presence of PPADS (10 μM). PPADS partially prevented the loss of viability induced by SO-Aβ. Control: 100 ± 2%; Aβ: 61 ± 1%, P < 0.0001 vs control; Aβ+PPADS: 94 ± 4%, P = 0.260 vs control, P = 0.002 vs Aβ; PPADS: 96 ± 7%, P = 0.705 vs control, P = 0.002 vs Aβ, FCCP: 3 ± 1%, n = 5. ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

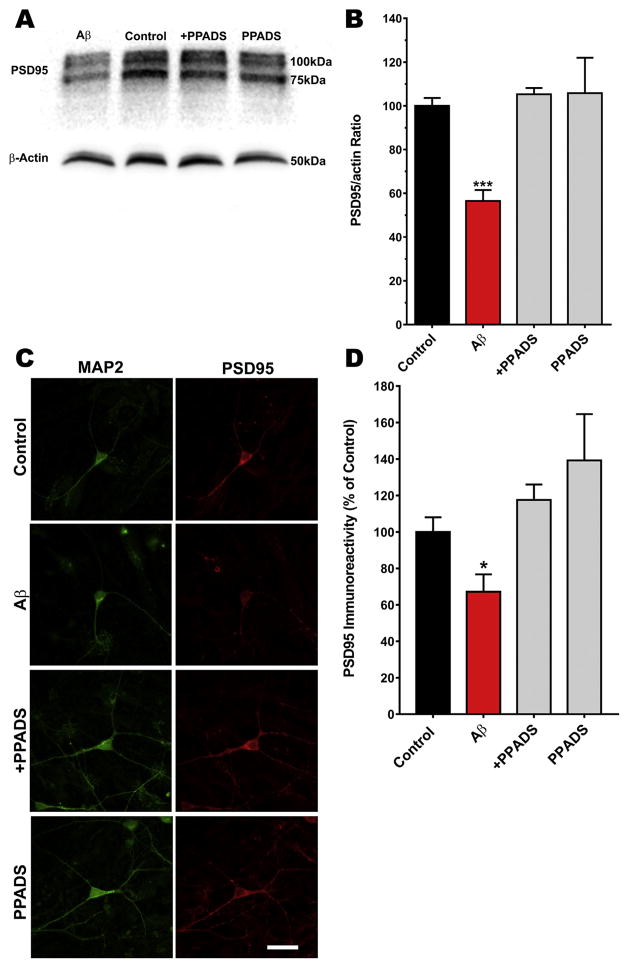

We next decided to correlate the effect of SO-Aβ on the post-synaptic component using PSD95, a postsynaptic density protein, as a marker. Using Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A), we observed that SO-Aβ (24 h) reduced the levels of PDS95/actin ratio compared with the control values (0.59 vs 1.06 respectively) in primary hippocampal cultures, while co-incubation with PPADS exhibited a PSD95/actin ratio similar to control (1.12; Fig. 2B). We also performed immunocytochemistry of hippocampal neurons labeled with specific antibodies to MAP-2 (green) and PSD95 (red) to confirm that the presence of PPADS preserved the postsynaptic proteins (Fig. 2C), similar to the results with SV2; and the quantification of inmunoreactivity (Fig. 2D) corroborate it the contribution to maintain the synaptic structure and communications. Taken together, the inhibition of P2XRs and modulation of purinergic tone may interfere with the toxic mechanism of SO-Aβ and help to maintain the functionality of the neuronal network. These results strongly support the hypothesis that the synaptic silencing induced by SO-Aβ could be mediated or potentiated by the activation of purinergic receptors, and suggests that the alterations in the levels of pre- and postsynaptic proteins is potentiated by P2XR over-activation (due to the ATP leakage by SO-Aβ).

Fig. 2.

PSD95 reduction is prevented by a P2XR antagonist in neurons treated with SO-Aβ. A) Representative Western Blot of the effect of SO-Aβ and PPADS (10 μM) in primary hippocampal cultures (12 DIV) treated for 24 h. B) Quantification of the immunoreactive bands for PSD95 from the Western Blot. Control: 100 ± 2.8; Aβ: 55.6 ± 4.7, P = 0.0002 vs control; Aβ+PPADS: 105.6 ± 2.8, P = 0.286 vs control, P = 0.0001 vs Aβ, PPADS: 10.6 ± 16.04, P = 0.742 vs control, P = 0.035 vs Aβ. n = 3. ***P < 0.001 vs. Control C) Representative images of hippocampal neurons (12 DIV, control) showing PSD95 immunoreactivity in control, Aβ (0.5 μM, 24 h), Aβ+PPADS (10 μM) or PPADS. In all images MAP2 is in green, PSD95 in red, scale bar 20 μm. D) Quantification of the immunofluorescence of PSD95, control: 100 ± 9%; Aβ: 67 ± 13%; Aβ+PPADS: 119 ± 10%; PPADS: 138 ± 27%. *P < 0.05 vs. control. n = 3. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

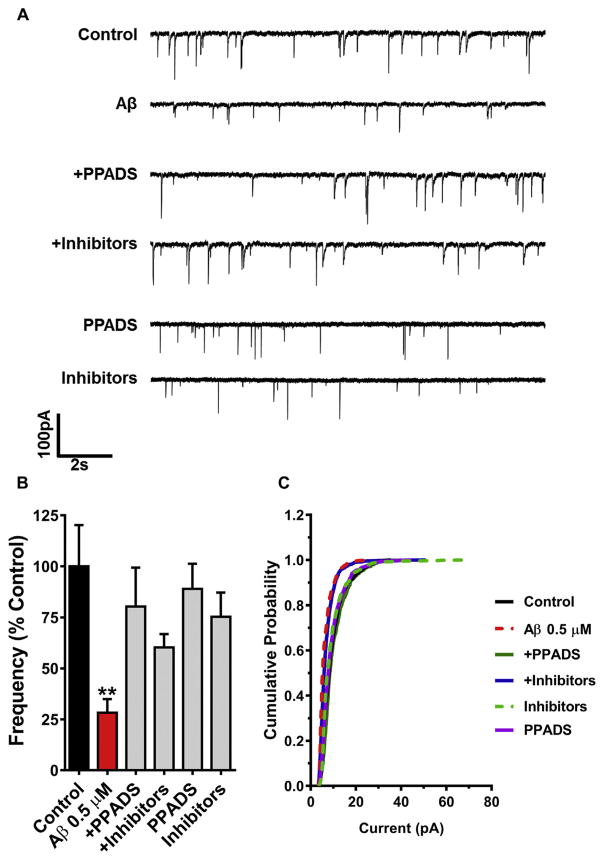

To correlate the previous results in this study with the functional effects of purinergic modulators on spontaneous synaptic currents in neurons chronically treated with SO-Aβ, we evaluated the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) in the presence and absence of: i) PPADS (10 μM), and ii) a cocktail to hydrolyze ATP and block any adenosine contribution (referred to as “+ inhibitors”), composed of apyrase (3U/ml, an enzyme with phosphatase activity that hydrolyzes ATP and ADP to AMP) and an adenosine A1 antagonist, DPCPX (1 μM). Complementary to that observed with acute exposure (Sáez-Orellana et al., 2016), we found that chronic SO-Aβ significantly decreased mEPSC frequency to ~30% of control (Fig. 3A and B), supporting the idea that SO-Aβ induces synaptic disconnection. Using the pharmacological strategy designed to prevent over-activation of P2XRs by endogenous ATP leakage, we observed that mEPSC frequency recovered to around 80% of control (with PPADS), and close to 60% in the “+ inhibitors” condition (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, SO-Aβ significantly reduced the average amplitude of mEPSCs, and again, inhibition of purinergic modulation was able to prevent the decrease induced by Aβ treatment (Fig. 3C). It is worth noting that PPADS showed a more robust effect than the combination of apyrase and DPCPX, which could be due to the diminishment of apyrase activity over time during incubation. Overall, these results suggest that the toxic effect of SO-Aβ is mediated in part by P2XRs.

Fig. 3.

Chronic pharmacological blockade of P2XR prevents neuronal network silencing. A) Representative traces of mEPSC in presence of SO-Aβ (0.5 μM), PPADS (10 μM) or apyrase (3U/ml) + DPCPX (1 μM) (Inhibitors). B) Quantification of mEPSC frequency in control: 100 ± 20%; Aβ: 28 ± 7%, P = 0.006 vs control; Aβ+PPADS: 80 ± 19%, P = 0.488 vs control, P = 0.027 vs Aβ; Aβ+Inhibitors: 60.3 ± 6.5%, P = 0.088 vs control, P = 0.002 vs Aβ; PPADS: 89 ± 12.3%, P = 0.647 vs control, P = 0.002 vs Aβ; Inhibitors: 75 ± 12%, P = 0.309 vs control, P = 0.403 vs Aβ; n = 14–19. C) Cumulative probability analysis of mEPSC showing that Aβ induces a left-shift in the curve indicating a decrease in the amplitude of mEPSC (P < 0.0001, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). This effect was prevented only by PPADS (P = 0.544, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). The inhibitors curve is similar to Aβ (P < 0.0001 vs control, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). **P < 0.01 vs. Control.

3.2. SO-Aβ increases the expression of P2XR

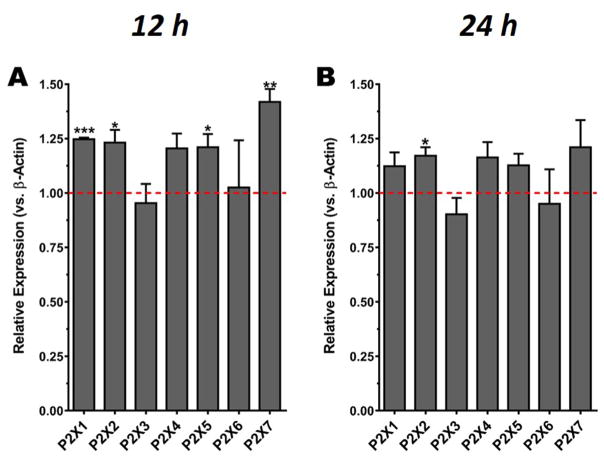

Different studies have shown, for example, that the expression of P2X7Rs is increased in the brains of post-mortem AD patients, as well as in animal models of the disease (McLarnon et al., 2006), suggesting the possibility that P2XR changes its expression levels contributing to SO-Aβ toxicity. Therefore, we used RT-qPCR to evaluate if some of the P2XR subtypes present in hippocampal neurons are changed and might be implicated in the cytotoxicity observed in the presence of chronic SO-Aβ. The changes in expression of all seven subtypes were studied at different incubation times (3, 6, 12 and 24 h) of SO-Aβ treatment. We found no significant changes in the expression of any subunits at 3 and 6 h (data not shown); however, there was a significant increase in the expression of P2X1R, P2X2R, P2X5R and P2X7R after 12 h of incubation (Fig. 4A). Additionally, after 24 h of treatment, P2X2R remained significantly increased (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that SO-Aβ increases the expression of some P2X subunits in sub-chronic or chronic treatments, and that the expected outcome of the increased expression is a potentiation of purinergic transmission with cytotoxic consequences to the neurons. In addition to β-actin as main housekeeping, we also assayed GADPH as a second reference gene, and a reference index obtained with the geometric mean of Ct for both reference genes showed similar results (not shown; Pfaffl, 2001).

Fig. 4.

SO-Aβ induces changes in the mRNA expression levels of P2X subunits. A) Quantification of relative mRNA for P2X subunits at 12 h of treatment with Aβ (0.5 μM) revealed that the subunits P2X1, 2, 5 and 7 had a significant increase in their expression (P2X1: 1.25 ± 0.007, P = 0.0009; P2X2: 1.23 ± 0.06, P = 0.029; P2X5: 1.21 ± 0.06, P = 0.039; P2X7: 1.42 ± 0.06, P = 0.019; P2X3: 0.95 ± 0.09, P = 0.636; P2X4: 1.21 ± 0.07, P = 0.056; P2X6: 1.03 ± 0.22, P = 0.918). B) Quantification of the relative expression of P2X at 24 h of treatment (Aβ, 0.5 μM) showing that at this time point only P2X2 remained significantly increased (P2X2: 1.2 ± 0.04, P = 0.022; P2X1: 1.1 ± 0.06, P = 0.152; P2X3: 0.9 ± 0.08, P = 0.286; P2X4: 1.16 ± 0.07, P = 0.110; P2X5: 1.13 ± 0.05, P = 0.096; P2X6: 0.95 ± 0.15, P = 0.783; P2X7: 1.21 ± 0.13, P = 0.193), n = 5. *P < 0.05 vs control, **P < 0.01 vs control, ***P < 0.001 vs control. Dashed line indicates the basal expression of each receptor subtype (control conditions).

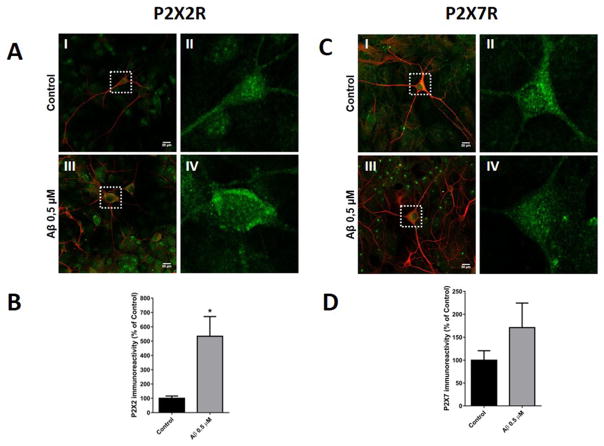

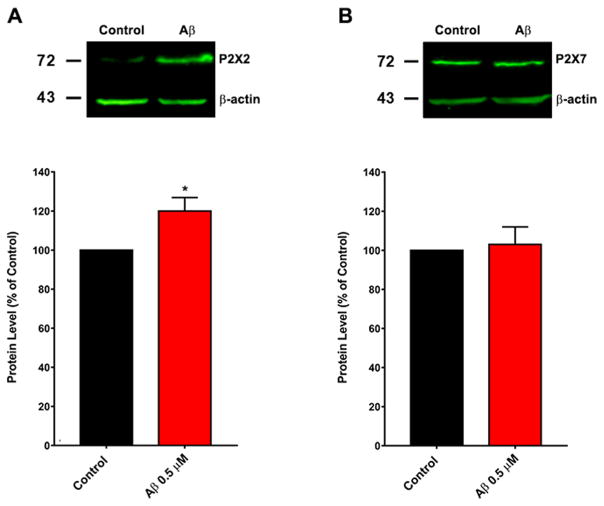

P2XRs have significant Ca2+ permeability, especially P2X2 (Liang et al., 2015), representing an important source that could contribute to the Ca2+ overload that is thought to underlie the excitotoxic effects of Aβ (Egorova et al., 2015). To corroborate these observations, we examined this chronic increase in P2X2R using immunocytochemistry and western blot in hippocampal neurons. Fig. 5A shows neurons labeled with specific antibodies to MAP-2 (red) and P2X2R (green) in control condition (Fig. 5A–I) and the magnification of the neuron inside of white square (Fig. 5A–II), and treatment with SO-Aβ (Fig. 5–III) and the respective magnification of one neuron under this condition (Fig. 5A–IV). The immunoreactivity to P2X2R increased 4 fold above control conditions (Fig. 5B) and these results correlate with the RT-qPCR data; while the same protocol to analyze P2X7R (Fig. 5C) did not show significant differences in the immunoreactivity (Fig. 5D). The same results were obtained in primary hippocampal culture when P2X2R and P2X7R protein levels were quantified by western blot (Fig. 6A and B); using the same experimental conditions.

Fig. 5.

P2X2R immunocytochemistry of hippocampal neurons treated with SO-Aβ. A-I) Representative image of hippocampal neuron (10 DIV) in control conditions stained with MAP-2 (red) and P2X2 receptor subunit (green, scale bar 20 μm). A-II) Magnification of control neuron with immunostaining for P2X2R (green). A-III) SO-Aβ treated neuron and staining in the same conditions as Aa. A-IV) Magnification of SO-Aβ treated neuron with immunostaining for P2X2R (green). B) Quantification of P2X2R immunoreactivity in SO-Aβ treated neurons with respect to control conditions (n = 4, * vs control condition). C-I) Representative image of a hippocampal neuron (10 DIV) in control conditions stained with MAP-2 (red) and P2X7 receptor subunit (green, scale bar 20 μm). C-II) Magnification of control neuron with immunostaining for P2X7R (green). C-III) SO-Aβ treated neuron and staining in the same conditions as Aa. C-IV) Magnification of SO-Aβ treated neuron with immunostaining for P2X7R (green). D) Quantification of P2X7R immunoreactivity in SO-Aβ treated neurons with respect to control conditions (n = 4).

Fig. 6.

Changes in P2X2R and P2X7R expression in hippocampal cultures treated with SO-Aβ. A: Quantification of P2X2R protein levels (lower) corresponding to the western blot (upper) in hippocampal cell cultures treated with Aβ (0.5 μM) (n = 4). B: Quantification of P2X7R protein levels (lower) corresponding to the western blot (upper) in neurons treated with Aβ (0.5 μM) (n = 4).

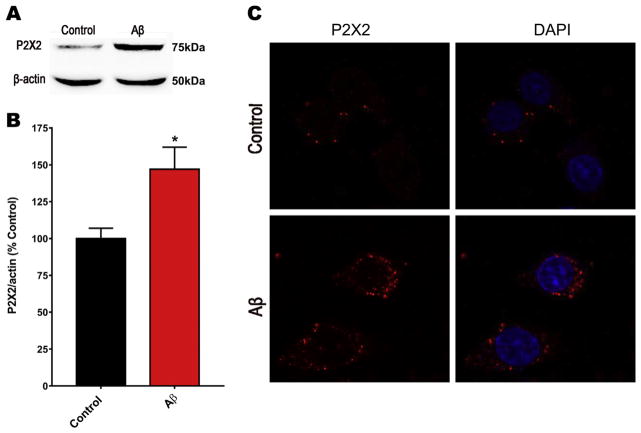

These results support the idea that the most relevant P2XR overexpressed in neurons would be P2X2R, while P2X7R could be important for other cells in primary hippocampal cultures, as is suggested in the literature. To corroborate these observations, we treated PC12 cells, a cell line with neuronal lineage, using the same protocol for hippocampal neurons. Western blot results demonstrated that cells treated 24 h with SO-Aβ had increased P2X2R protein levels as observed in Fig. 7A and quantified in Fig. 7B, showing an increase of approximately 45%. Interestingly these results were confirmed by immunofluorescence as observed in Fig. 7C where P2X2R was labeled in red. These data reinforce the idea that amyloid peptide toxicity and purinergic neuromodulation are tightly coupled by overexpression of P2XR and an increase in purinergic tone, mainly mediated by P2X2R in neurons and neuronal-like cells.

Fig. 7.

Changes in P2X2R levels on PC12 cells after treatment with SO-Aβ. A). Representative image of the western blot analysis for P2X2R after treatment with Aβ during 24 h. B) Quantification for the P2X2R western blot analysis *p < 0.05; n = 4. C) Representative image of immunofluorescence for P2X2R (red) done in PC12 cells in control and after treatment with SO-Aβ (0.5 μM) during 24 h. DAPI (blue) was used to stain the nuclei. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

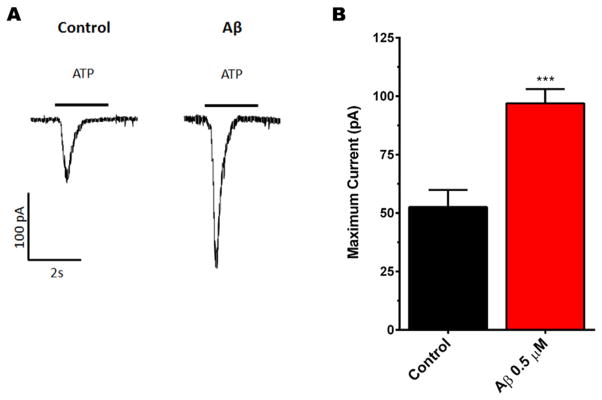

To further support our hypothesis that P2XRs are overexpressed with chronic treatment of SO-Aβ and that it is a functional over-expression that can induce changes in the neuronal network, we measured current amplitude evoked by application of exogenous ATP (1 mM) on neurons exposed to Aβ (0.5 μM, 24 h) using patch clamp techniques (Fig. 8A). We found that SO-Aβ effectively increased ATP-evoked currents to almost double of control currents (control: 53 ±7 pA; Aβ: 97 ± 6 pA or 183% of control, Fig. 8B); while it had no effect on activation (control τACT: 0.27 ± 0.05 seg; Aβ τACT: 0.23 ± 0.04 seg, P = 0.567, t-test) or inactivation kinetics (control τINACT: 0.33 ± 0.05 seg; Aβ τINACT: 0.23 ± 0.05 seg, P = 0.188, t-test). Thus, the most plausible explanation for these increments in amplitude after SO-Aβ treatment is related with the increased functional expression of P2X2 in the plasma membrane, without altering the gating properties of the receptors.

Fig. 8.

SO-Aβ increased the amplitude of ATP-evoked currents. A) Representative currents obtained from control and SO-Aβ treated neurons; stimulus ATP (1 mM), 5 s. The upper traces represent neurons with slow desensitization, lower traces are from neurons with fast desensitization. B) Quantification of ATP-evoked currents. SO-Aβ induced a significant increase in the amplitude of the currents. Control: 53±7 pA; Aβ: 97±6 pA, ***P = 0.0002 vs control conditions, N = 18, 15, respectively.

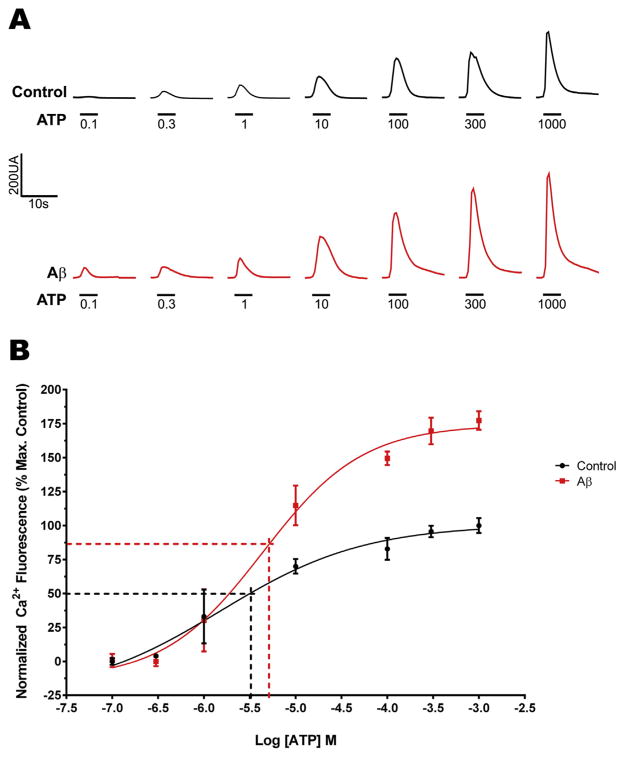

Finally, to corroborate that increased P2X2 receptor density in the plasma membrane induced by SO-Aβ is functional and that their activation induces a Ca2+ overload, we used Ca2+ micro-fluorimetry to measure concentration-response curves with ATP (0.1–1000 μM) as the agonist. As shown in Fig. 9A, we observed an increase in the amplitude of cytosolic Ca2+ signals evoked by all ATP concentrations tested in neurons pretreated with SO-Aβ. These increases were similar to those observed on the amplitude of the ATP-evoked currents (Fig. 8A), confirming the presence of functional receptors in the plasma membrane that potentiate SO-Aβ cytotoxicity. Additionally, we also observed a significant increase in apparent EC50 for ATP in Aβ-treated neurons (Fig. 9B, control: 1.5 ± 0.14 μM; Aβ: 4.5 ± 0.15 μM, P = 0.0002, t-test), which could be related to the changes in expression of the observed P2X receptors (Coddou et al., 2011).

Fig. 9.

Changes in the Ca2+ influx evoked by ATP in neurons treated with SO-Aβ. A) Representative traces of Ca2+ influx obtained from control neurons (in black) or SO-Aβ treated neurons (in red) using increasing concentrations of ATP (5 s). B) Concentration-response curve for ATP. Values are normalized to the average maximum fluorescence obtained in control. Aβ increased the maximum response and produced a left shift in the curve of apparent EC50 vs control: 1.5 ± 0.14 μM; and Aβ: 4.5 ± 0.15 μM, P = 0.0002. Maximum response for control: 100 ± 6%; and Aβ: 177 ± 7%; P = 0.001, n = 3. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Our results suggest a new alternative to consider the purinergic transmission as a novel target for the Aβ toxicity mechanism. Under the experimental conditions of the present work, P2XR activation represents a functional contribution that may explain the neurodegeneration when Aβ is chronically present in the neuronal network. The synaptic uncoupling and neuronal network silencing were recovered when a P2XR inhibitor was present, and represent evidence that could support our working hypothesis. In parallel, the possibility that overstimulation of P2XR can modify its expression levels and the presence in the plasma membrane were corroborated by molecular biology strategies (RT-qPCR and immunocytochemistry), as well as by functional assays (electrophysiology and Ca2+ microfluorimetry). Additionally, the incubation of PPADS alone showed a significant increment in SV2 immunostaining versus control condition (145%, Fig. 1Ad,1B). This unexpected result can be interpreted as a compensatory response to the effect of P2XR activation on the neuronal network (without SO-Aβ), and correlate with previous effects reported in the literature (Xing et al., 2008).

The changes in the expression levels of P2X1R, P2X5R, P2X7R, and especially P2X2R, represent a functional contribution that may explain, at least partially, the synaptic toxicity in our model. To try to understand the role of each overexpressed subunit, it is important to take into consideration the following: i) The P2X1 expression increment could be non-relevant since P2X1R has a fast desensitization kinetic (τdes: 64.8 ± 7.8 ms, Coddou et al., 2011) and also a fast internalization rate (Lalo et al., 2008), thus their contribution must be minor; and ii) P2X5 (as well P2X6R) has been described as part of a group located mainly in the cytoplasm (Murrell-Lagnado and Qureshi, 2008; Murrell-Lagnado and Robinson, 2013; Ormond et al., 2006). Therefore, the potential contribution of these subunits could be minimal; while the increments in P2X7 and P2X2 receptors appear to be the most important since these two subunits have been described as being prevalent in the plasma membrane (Chaumont et al., 2004; Murrell-Lagnado and Qureshi, 2008; Murrell-Lagnado and Robinson, 2013; Richler et al., 2011; Shrivastava et al., 2013). However, P2X7 receptors have been described as markers (as well as P2X4) for microglia activation (Anccasi et al., 2012; Avignone et al., 2008; Cavaliere et al., 2003; Choi et al., 2007; Doná et al., 2009) and are implicated in cell death (Anccasi et al., 2012; Cho et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2007; Ireland et al., 2004; León et al., 2008; Marcoli et al., 2008); while other reports have suggested contributions in cell survival (Amstrup and Novak, 2003; Gendron et al., 2003; Neary et al., 2003; Ortega et al., 2010). The role of P2X7R on microglia activation correlated with our data. The increments in the levels of messenger RNA by RT-qPCR were not correlated to the results for protein levels shown with western blot and immunocytochemistry studies in hippocampal neurons. Thus, the increase in messenger RNA observed with RT-qPCR could be attributable to the presence of their mRNA from glial cells. Taken together, the increased size of the evoked currents and sustained increase in cytosolic Ca2+ signals observed in neurons could represent the “point of no return” for the toxic effects induced by SO-Aβ and could be mediated by P2X2, as well as P2X7; two receptor subunits that are most likely responsible for the transmembrane Ca2+ fluxes seen upon persistent exposure to the peptide.

In this study, it appears that P2X2 represent the most relevant receptor contributing to these effects due to their increased expression in the plasma membrane in the presence of SO-Aβ as observed in Fig. 5. Moreover, P2X2 has been described to interact with the APP anchoring protein Fe65 and modulate the processing of APP and Aβ levels (Lau et al., 2008; Masin et al., 2006), further promoting the vicious cycle related to SO-Aβ toxicity. Therefore, the P2X2R appears to be a crucial component for overall cellular Aβ pathogenicity. However, it is unlikely that these results are mediated only by P2X2, without the potential contribution of other receptor subtypes or heteromeric conformations that need to be clarified in future studies.

5. Conclusions

The involvement of P2X2 or P2XR in AD suggests that this class of ligand-gated ion channel may be a beneficial drug target in the battle to prevent the onset or ameliorate the symptoms of a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including dementias.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was funded by FONDECYT 1130747 (JF) and 1161078 (JF). TSG and PAG are PhD fellow of CONICYT (21160392 and 201161295 respectively).

We thank Laurie Aguayo for edition of this manuscript, Ixia Cid and CMA-BIOBIO for their technical support.

Abbreviations

- APP

Amyloid Precursor Protein

- ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate

- BAPTA

1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- CNQX

6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- D-AP5

(2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid

- DMEM

Dulbecco modified Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium

- DMSO

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline

- DPCPX

8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- EMCCD

Electron-multiplying charge-coupled device

- FCCP

Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GTP

Guanosine Triphosphate

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HRP

Horseradish peroxidase

- LTP

Long Term Potentiation

- MAP2

Microtubule Associated Protein 2

- MEM

Minimum Essential Medium

- mEPSC

miniature Excitatory Post Synaptic Current

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NIH

National Institute of Health

- NMDAR

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor

- P2XR

Purinergic Ionotropic Receptor

- PPADS

PyridoxalPhosphate-6-Azophenyl-2′,4′-DiSulfonic acid

- PrPC

Prion Protein

- PSD95

Postsynaptic Density Protein of 95 kDa

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SV2

Synaptic Vesicle glycoprotein 2

- TBS-T

Tris-Buffered Saline-Tween 20

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author contributions

FSO and JF designed the experiments. FSO, TSG, JDP, TCM and PAG performed the experiments, MCFF perform immunocytochemistry in neurons. TME, JF and FSO wrote the article. LG and GY discussed the results.

References

- Allgaier C, Reinhardt R, Schädlich H, Rubini P, Bauer S, Reichenbach A, Illes P. Somatic and axonal effects of ATP via P2X2 but not P2X7 receptors in rat thoracolumbar sympathetic neurones. J Neurochem. 2004;90:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstrup J, Novak I. P2X7 receptor activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases ERK1 and ERK2 independently of Ca2+ influx. Biochem J. 2003;374:51–61. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anccasi R, Ornelas I, Cossenza M, Persechini P, Ventura A. ATP induces the death of developing avian retinal neurons in culture via activation of P2X7 and glutamate receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2012:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9324-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arispe N, Diaz JC, Simakova O. Aβ ion channels. Prospects for treating Alzheimer’s disease with Aβ channel blockers. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) 2007;1768:1952–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arispe N, Rojas E, Pollard HB. Alzheimer disease amyloid b protein forms calcium channels in bilayer membranes: blockade by tromethamine and aluminum. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:567–571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avignone E, Ulmann L, Levavasseur F, Rassendren F, Audinat E. Status Epilepticus induces a particular microglial activation state characterized by enhanced purinergic signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9133–9144. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1820-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter AW, Choi SJ, Sim JA, North RA. Role of P2X4 receptors in synaptic strengthening in mouse CA1 hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaliere F, Florenzano F, Amadio S, Fusco FR, Viscomi MT, D’Ambrosi N, Vacca F, Sancesario G, Bernardi G, Molinari M, Volonté C. Up-regulation of P2X2, P2X4 receptor and ischemic cell death: prevention by P2 antagonists. Neuroscience. 2003;120:85–98. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coddou C, Yan Z, Obsil T, Huidobro-Toro JP, Stojilkovic SS. Activation and regulation of purinergic P2X receptor channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:641–683. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont S, Jiang LH, Penna A, North RA, Rassendren F. Identification of a trafficking motif involved in the stabilization and polarization of P2X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29628–29638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Choi IS, Jang IS. P2X7 receptors enhance glutamate release in hippocampal hilar neurons. NeuroReport. 2010;21:865–870. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833d9142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HB, Ryu JK, Kim SU, McLarnon JG. Modulation of the purinergic P2X7 receptor attenuates lipopolysaccharide-mediated microglial activation and neuronal damage in inflamed brain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4957–4968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5417-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmellah A, Rayah A, Auger R, Cuif MH, Prigent M, Arpin M, Alcover A, Delarasse C, Kanellopoulos JM. Ezrin/radixin/moesin are required for the purinergic P2X7 receptor (P2X7R)-dependent processing of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34583–34595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker H, Jürgensen S, Adrover MF, Brito-Moreira J, Bomfim TR, Klein WL, Epstein AL, De Felice FG, Jerusalinsky D, Ferreira ST. N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptors are required for synaptic targeting of Alzheimer’s toxic amyloid-β peptide oligomers. J Neurochem. 2010;115:1520–1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delarasse C, Auger R, Gonnord P, Fontaine B, Kanellopoulos JM. The purinergic receptor P2X7 triggers α-Secretase-dependent processing of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2596–2606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Virgilio F, Ceruti S, Bramanti P, Abbracchio MP. Purinergic signalling in inflammation of the central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doná F, Ulrich H, Persike DS, Conceição IM, Blini JP, Cavalheiro EA, Fernandes MJS. Alteration of purinergic P2X4 and P2X7 receptor expression in rats with temporal-lobe epilepsy induced by pilocarpine. Epilepsy Res. 2009;83:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egorova P, Popugaeva E, Bezprozvanny I. Disturbed calcium signaling in spinocerebellar ataxias and Alzheimer’s disease. Semin Cell & Dev Biol. 2015;40:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira IL, Bajouco LM, Mota SI, Auberson YP, Oliveira CR, Rego AC. Amyloid b peptide 1–42 disturbs intracellular calcium homeostasis through activation of GluN2B-containing N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in cortical cultures. Cell Calcium. 2012;51:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366:2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba J, Dibarrart A, Saez-Orellana F, Fuentes-Fuentes MC, Oyanedel CN, Guzmán J, Perez C, Becerra J, Aguayo LG. Synaptic silencing and plasma membrane dyshomeostasis induced by amyloid-β peptide are prevented by Aristotelia chilensis enriched extract. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012;31:879–889. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba J, Dibarrart AJ, Fuentes-Fuentes MC, Saez-Orellana F, Quiñones K, Guzmán L, Perez C, Becerra J, Aguayo LG. Synaptic failure and adenosine triphosphate imbalance induced by amyloid-β aggregates are prevented by blueberry-enriched polyphenols extract. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:1499–1508. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron FP, Neary JT, Theiss PM, Sun GY, Gonzalez FA, Weisman GA. Mechanisms of P2X7 receptor-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in human astrocytoma cells. Am J Physiol - Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C571–C581. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00286.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland MF, Noakes PG, Bellingham MC. P2X7-like receptor subunits enhance excitatory synaptic transmission at central synapses by presynaptic mechanisms. Neuroscience. 2004;128:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Ajit D, Peterson TS, Wang Y, Camden JM, Gibson Wood W, Sun GY, Erb L, Petris M, Weisman GA. Nucleotides released from Aβ1–42-treated microglial cells increase cell migration and Aβ1–42 uptake through P2Y2 receptor activation. J Neurochem. 2012;121:228–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal R, Lin H, Quist AP. Amyloid b ion channel: 3D structure and relevance to amyloid channel paradigm. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) 2007;1768:1966–1975. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalo U, Pankratov Y, Wichert SP, Rossner MJ, North RA, Kirchhoff F, Verkhratsky A. P2X1 and P2X5 subunits form the functional P2X receptor in mouse cortical astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5473–5480. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1149-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau KF, Chan WM, Perkinton MS, Tudor EL, Chang RCC, Chan HYE, McLoughlin DM, Miller CCJ. Dexras1 interacts with FE65 to regulate FE65-amyloid precursor protein-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34728–34737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801874200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laube B. Potentiation of inhibitory glycinergic neurotransmission by Zn2+: a synergistic interplay between presynaptic P2X2 and postsynaptic glycine receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1025–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-b oligomers. Nature. 2009;457:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nature07761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León D, Sánchez-Nogueiro J, Marín-García P, Miras-Portugal MT. Glutamate release and synapsin-I phosphorylation induced by P2X7 receptors activation in cerebellar granule neurons. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesné S, Teng Koh M, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Gable CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-b protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nat Lett. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Samways DSK, Wolf K, Bowles EA, Richards JP, Bruno J, Dutertre S, DiPaolo RJ, Egan TM. Quantifying Ca2+ current and permeability in ATP-gated P2X7 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7930–7942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.627810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madry C, Attwell D. Receptors, ion channels, and signaling mechanisms underlying microglial dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:12443–12450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.637157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoli M, Cervetto C, Paluzzi P, Guarnieri S, Alloisio S, Thellung S, Nobile M, Maura G. P2X7 pre-synaptic receptors in adult rat cerebrocortical nerve terminals: a role in ATP-induced glutamate release. J Neurochem. 2008;105:2330–2342. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masin M, Kerschensteiner D, Dümke K, Rubio ME, Soto F. FE65 interacts with P2X2 subunits at excitatory synapses and modulates receptor function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4100–4108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLarnon JG, Ryu JK, Walker DG, Choi HB. Upregulated expression of purinergic P2X7 receptor in alzheimer disease and amyloid-b peptide-treated microglia and in peptide-injected rat Hippocampus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:1090–1097. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240470.97295.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell-Lagnado RD, Qureshi OS. Assembly and trafficking of P2X purinergic receptors (Review) Mol Membr Biol. 2008;25:321–331. doi: 10.1080/09687680802050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell-Lagnado RD, Robinson LE. The trafficking and targeting of P2X receptors. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013:7. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary JT, Kang Y, Willoughby KA, Ellis EF. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by stretch-induced injury in astrocytes involves extra-cellular ATP and P2 purinergic receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2348–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02348.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orellana JA, Froger N, Ezan P, Jiang JX, Bennett MVL, Naus CC, Giaume C, Sáez JC. ATP and glutamate released via astroglial connexin 43 hemichannels mediate neuronal death through activation of pannexin 1 hemichannels. J Neurochem. 2011;118:826–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormond SJ, Barrera NP, Qureshi OS, Henderson RM, Edwardson JM, Murrell-Lagnado RD. An uncharged region within the N Terminus of the P2X6 receptor inhibits its assembly and exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1692–1700. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega F, Pérez-Sen R, Morente V, Delicado E, Miras-Portugal M. P2X7, NMDA and BDNF receptors converge on GSK3 phosphorylation and cooperate to promote survival in cerebellar granule neurons. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:1723–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0278-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parodi J, Sepúlveda FJ, Roa J, Opazo C, Inestrosa NC, Aguayo LG. B-amyloid causes depletion of synaptic vesicles leading to neurotransmission failure. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:2506–2514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvathenani LK, Tertyshnikova S, Greco CR, Roberts SB, Robertson B, Posmantur R. P2X7 mediates superoxide production in primary microglia and is up-regulated in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13309–13317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Espinoza MP, Gallegos S, Opazo C, Aguayo LG. Alzheimer’s Aβ interacts with cellular prion protein inducing neuronal membrane damage and synaptotoxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1369–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, Wu Y-T, Prina M, Chan KY. World alzheimer report 2015: the global impact of dementia an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. In: Prince M, editor. World Alzheimer Report. Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI); London, UK: 2015. p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Richler E, Shigetomi E, Khakh BS. Neuronal P2X2 receptors are mobile ATP sensors that explore the plasma membrane when activated. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16716–16730. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3362-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royle SJ, Bobanović LK, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Identification of a non-canonical tyrosine-based endocytic motif in an ionotropic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35378–35385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royle SJ, Qureshi OS, Bobanović LK, Evans PR, Owen DJ, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Non-canonical YXXGΦ endocytic motifs: recognition by AP2 and preferential utilization in P2X4 receptors. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3073–3080. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Orellana F, Godoy PA, Bastidas CY, Silva-Grecchi T, Guzmán L, Aguayo LG, Fuentealba J. ATP leakage induces P2XR activation and contributes to acute synaptic excitotoxicity induced by soluble oligomers of β-amyloid peptide in hippocampal neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2016;100:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda FJ, Fierro H, Fernandez E, Castillo C, Peoples RW, Opazo C, Aguayo LG. Nature of the neurotoxic membrane actions of amyloid-β on hippocampal neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:472–481. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava AN, Rodriguez PC, Triller A, Renner M. Dynamic micro-organization of P2X7 receptors revealed by PALM based single particle tracking. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013:7. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Masuda T, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Inoue K. P2X4 receptors and neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013:7. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma R, Chai Y, Troncoso J, Gu J, Xing H, Stojilkovic S, Mattson M, Haughey N. Amyloid-β induces a caspase-mediated cleavage of P2X4 to promote purinotoxicity. NeuroMolecular Med. 2009;11:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Lu J, Li J. Purinergic P2X receptors presynaptically increase glutamatergic synaptic transmission in dorsolateral periaqueductal gray. Brain Res. 2008;1208:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]