Abstract

Understanding how incompletely cleared primary tumors transition from minimal residual disease (MRD) into treatment-resistant, immune-invisible recurrences has major clinical significance. We show here that this transition is mediated through the subversion of two key elements of innate immunosurveillance. In the first, the role of TNFα changes from an antitumor effector against primary tumors into a growth promoter for MRD. Second, whereas primary tumors induced a natural killer (NK)–mediated cytokine response characterized by low IL6 and elevated IFNγ, PD-L1hi MRD cells promoted the secretion of IL6 but minimal IFNγ, inhibiting both NK-cell and T-cell surveillance. Tumor recurrence was promoted by trauma- or infection-like stimuli inducing VEGF and TNFα, which stimulated the growth of MRD tumors. Finally, therapies that blocked PD-1, TNFα, or NK cells delayed or prevented recurrence. These data show how innate immunosurveillance mechanisms, which control infection and growth of primary tumors, are exploited by recurrent, competent tumors and identify therapeutic targets in patients with MRD known to be at high risk of relapse.

Introduction

Tumor dormancy followed by potentially fatal, aggressive recurrence represents a major clinical challenge for successful treatment of malignant disease, as recurrence occurs at times that cannot be predicted (1–6). Tumor dormancy is the time following first-line treatment in which a patient is apparently free of detectable tumor, but after which local or metastatic recurrence becomes clinically apparent (2–8). Dormancy results from the balance of tumor–cell proliferation and death through apoptosis, lack of vascularization, immunosurveillance (2–5, 9–13), and cancer cell dormancy and growth arrest (2–4). Dormancy is characterized by presence of residual tumor cells [minimal residual disease (MRD); ref. 14] and can last for decades (2, 5, 15–17).

Recurrences are often phenotypically very different from primary tumors, representing the end product of in vivo selection against continued sensitivity to first-line treatment (18–28). Escape from first-line therapy is common, in part, because of the heterogeneity of tumor populations (29, 30), which include treatment-resistant subpopulations (31). Understanding the ways in which recurrent tumors differ from primary tumors would allow early initiation of rational, targeted second-line therapy. Identifying triggers that convert MRD into actively proliferating recurrence would allow more timely screening and early intervention to treat secondary disease (32).

To address these issues, we developed several different preclinical models in which suboptimal first-line treatment induced complete macroscopic regression, a period of dormancy or MRD, followed by local recurrence. Thus, treatment of either subcutaneous B16 melanoma or TC2 prostate tumors with adoptive T-cell transfer (21, 33–35), systemic virotherapy (36, 37), VSV-cDNA immunotherapy (38, 39), or ganciclovir chemotherapy (40–42) led to apparent tumor clearance (no palpable tumor) for > 40 to 150 days. However, with prolonged follow-up, a proportion of these animals developed late, aggressive local recurrences, mimicking the clinical situation in multiple tumor types (43–45). Recurrence was associated with elevated expression of several recurrence-specific antigens that were shared across tumor types, such as YB-1 and topoisomerase-Iiα (TOPO-IIα) (44), as well as tumor type–specific recurrence antigens (45).

Here, we show that the transition from MRD into actively proliferating recurrent tumors is mediated through the subversion of two key elements of innate immunosurveillance of tumors, recognition by natural killer (NK) cells and response to TNFα. These data show how the transition from MRD to active recurrence is triggered in vivo and how recurrences use innate antitumor immune effector mechanisms to drive their own expansion and escape from immunosurveillance. Understanding these mechanisms can potentially lead to better treatments that delay or prevent tumor recurrence.

Materials and Methods

Mice, cell lines, and viruses

Female 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The OT-I mouse strain [on a C57BL/6 (H2-Kb) background] was bred at the Mayo Clinic and expresses the transgenic T-cell receptor Vα2/Vβ5 specific for the SIINFEKL peptide of ovalbumin in the context of MHC class I, H-2Kb as described previously (46). Pmel-1 transgenic mice (on a C57BL/6 background) express the Vα1/Vβ13 T-cell receptor that recognizes amino acids 25–33 of gp100 of pmel-17 presented by H2-Db MHC class I molecules (47). Pmel-1 breeding colonies were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory at 6 to 8 weeks of age and were subsequently bred at Mayo Clinic under normal housing (not pathogen-free) conditions.

The B16ova cell line was derived from a B16.F1 clone transfected with a pcDNA3.1ova plasmid (33). B16ova cells were grown in DMEM (HyClone) containing 10% FBS (Life Technologies) and G418 (5 mg/mL; Mediatech) until challenge. B16tk cells were derived from a B16.F1 clone transfected with a plasmid expressing the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSVtk) gene. Following stable selection in puromycin (1.25 μg/mL), these cells were shown to be sensitive to ganciclovir (cymevene) at 5 μg/mL (40, 41). For experiments where cells were harvested from mice, tumor lines were grown in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech). Where appropriate, adherent cells were confirmed to be B16tk cells by the expression of melanin and by qRT-PCR for the HSVtk gene. Cells were mycoplasma free and authenticated by morphology, growth characteristics, and PCR for melanoma-specific gene expression (gp100, TYRP-1, and TYRP2) and biologic behavior before freezing. Cells were cultured less than 3 months after resuscitation.

Wild-type reovirus type 3 (Dearing strain) stock titers were measured by plaque assays on L929 cells (a kind gift from Dr. Kevin Harrington, Institute of Cancer Research, London, United Kingdom). Briefly, 6-well plates were seeded with 7.5 × 105 L929 cells per well in DEMEM plus 10% FBS and incubated overnight. Cells were washed once with PBS. One milliliter of serial dilutions of the test reovirus stocks was loaded into the 6-well plate in duplicate. Cells were incubated with virus for 3 hours. Media and virus were aspirated off the cells, and 2 ml of 1% Noble agar (diluted from a 2% stock with 2× DMEM plus 10% FBS) at 42°C was added to each well. Plates were incubated for 4 to 5 days until plaques were visible, and wells were then stained with 500 μL of 0.02% neutral red for 2 hours and plaques were counted. For in vivo studies, reovirus was administered intravenously at 2 × 107 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective dose) per injection.

In vivo experiments

C57BL/6J and B6.129S2−Il6tm1Kopf/J IL6 knockout mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All in vivo studies were approved by the Mayo IACUC. Mice were challenged subcutaneously with 5 × 105 B16ova, B16tk, or B16 melanoma cells in 100 μL PBS (HyClone). Tumors were measured 3 times per week using Bel-Art SP Scienceware Dial-type calipers, and mice were euthanized with CO2 when tumors reached 1.0 cm diameter.

For suboptimal adoptive T-cell therapy (in which more than 50% of treated mice would undergo complete macroscopic regression followed by local recurrence), mice were treated intravenously with PBS or 106 4-day activated OT-I T cells on days 6 and 7 after B16ova injection as described previously (21, 43).

For ganciclovir chemotherapy experiments, C57BL/6 mice were treated with ganciclovir intraperitoneally at 50 mg/mL on days 6 to 10 and days 13 to 17 after subcutaneous B16tk injection.

For suboptimal, systemic virotherapy experiments, C57BL/6 mice with 5-day established B16 tumors were treated intraperitoneally with PBS or paclitaxel (PAC; Mayo Clinic Pharmacy) at 10 mg/kg body weight for 3 days followed by intravenous reovirus (2 × 07 TCID50) or PBS for 2 days. This cycle was repeated once and was modified from a more effective therapy described previously (36).

To prevent or delay tumor recurrences, mice were treated intravenously with anti–PD-1 (0.25 mg; catalog no. BE0146; Bio X Cell), anti-TNFα (1 μg; catalog no. AF-410-NA; R&D Systems), anti-asialo GM1 (0.1 mg; catalog no. CL8955; Cedarlane), or isotype control rat IgG (catalog no. 012-000-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch) antibody at times described in each experiment.

Establishment of MRD tumor–cell cultures from skin explants

Mice treated with ganciclovir, OT-I T cells, or reovirus that had no palpable tumors following regression and macroscopic disappearance for >40 days had skin from the sites of B16tk, B16ova, or B16 injection explanted. Briefly, skin was mechanically and enzymatically dissociated and approxomately 103 to 104 cells were plated in 24-well plates in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Twenty-four hours later, wells were washed three times with PBS, and 7 days later inspected microscopically for actively growing tumor–cell cultures.

qRT-PCR

B16 cells or MRD B16 cells expanded from a site of tumor injection for 72 hours in TNFα in vitro were cultured for 48 hours in serum-free medium. Cells were then harvested, and RNA was prepared with the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit. One microgram total RNA was reverse transcribed in a 20 μL volume using oligo-(dT) primers and the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (catalog no. 04379012001; Roche). A LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Kit was used to prepare samples according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1 ng of cDNA was diluted [neat (undiluted), 1:10, 1:100, 1:1,000] and amplified with gene-specific primers using GAPDH as a normalization control. Expression of the murine TOPO-IIα gene was detected using the forward 5′-GAGCCAAAAATGTCTTGTATTAG-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGATGTCTGCCCTTAGAAG-3′ primers. Expression of the murine GAPDH gene was detected using the forward 5′-TCATGACCACAGTCCATGCC-3′ and reverse 5′-TCAGCTCTGG-GATGACCTTG-3′ primers. Primers were designed using the NCBI Primer Blast primer designing tool.

Samples were loaded into a 96-well PCR plate in duplicate and ran on a LightCycler480 instrument (Roche). The threshold cycle (Ct) at which amplification of the target sequence was detected was used to compare the relative expression of mRNAs in the samples using the 2–ΔΔCt method.

Immune cell activation

Spleens and lymph nodes were immediately excised from euthanized C57BL/6 or OT-I mice and dissociated in vitro to achieve single-cell suspensions. Red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 minutes. Cells were resus-pended at 1 × 106 cells/mL in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM; Gibco) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 40 μmol/L 2-BME. Cells were cocultured with target B16 or B16MRD cells as described in the text. Cell-free supernatants were then collected 72 hours later and tested for IFNγ (Mouse IFNγ ELISA Kit; OptEIA, BD Biosciences) and TNFα (BD Biosciences) production by ELISA as directed in the manufacturer's instructions.

NK cells were prepared from spleens of naïfive C57BL/6 mice using the NK Cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) as described in the "NK cell isolation" section and cocultured with B16 or B16MRD target tumor cells at E:T ratios of 20:1. Seventy-two hours later, supernatants were assayed for IFNγ or IL6 by ELISA.

Cytokines and antibodies

Cytokines and cytokine-neutralizing antibodies were added to cultures upon plating of the cells and used at the following concentrations in vitro: VEGF165 (12 ng/mL; catalog no. CYF- 336; Prospec-Bio), TNFα (100 ng/mL; catalog no. 31501A; Pepro-tech), IL6 (100 pg/mL; catalog no. 216–16; PeproTech), anti-TNFα (0.4 μg/mL; catalog no. AF410NA; R&D Systems), universal IFNα (100 U; catalog no. 11200-2; R&D Systems), anti-IL6 (1 μg/mL; catalog no. MP5-20F3; BioLegend), LPS (25 ng/mL; catalog no. L4524; Sigma), and CpG (25 ng/mL; Mayo Clinic Oligonucleotide Core facility).

Immune cell depletion

Splenocyte and lymph node cultures were depleted of different immune cell types [asialo GM-1+ (NKs), CD4+, CD8+, CD11c+, or CD11b+ cells] by magnetic bead depletion [catalog no. 130-052-501 (NK); 130-104-454 (CD4); 130-104-075 (CD8); 130-108-338 (CD11c) and 130-049-601 (CD11b); Miltenyi Biotec] according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cultures were depleted using the RB6-8C5 (8 μg/mL; R&D Systems, catalog no. MAB1037) and 1A8 (1 μg/mL; BioLegend, catalog no. 127601) antibodies. 1A8 recognizes only Ly-6G, whereas clone RB6-8C5 recognizes both Ly-6G and Ly-6C. Ly6G is differentially expressed in the myeloid lineage on monocytes, macrophages, granulocytes, and peripheral neutrophils. RB6-8C5 is typically used for phenotypic analysis of monocytes, macrophages, and granulocytes, whereas 1A8 is typically used to characterize neutrophils.

NK-cell isolation and flow cytometry

Mouse NK cells were isolated from single-cell suspensions of the dissociated spleens of 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice using the NK Cell Isolation Kit II according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). In this protocol, T cells, dendritic cells, B cells, granulocytes, macrophages, and erythroid cells are indirectly magnetically labeled with a cocktail of biotin-conjugated antibodies and anti-biotin microbeads for 15 minutes. After depleting magnetically labeled cells, isolation and enrichment of unlabeled NK cells was confirmed by flow cytometry. Isolated NK cells were stained with CD3-FITC (catalog no. 100306; BioLegend), NK1.1-PE (catalog no. 108708; BioLegend), PD-1-Pe/Cy7 (catalog no. 109109; BioLegend), PD-L1-APC (catalog no. 124311; BioLegend) to distinguish enriched NK cells from CD3+ cells. Blood was taken either serially in an approximately 200 μL submandibular vein bleed or from cardiac puncture at the time of sacrifice. Blood was collected in heparinized tubes, washed twice with ACK lysis buffer, and resuspended in PBS for staining.

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out by the Mayo Microscopy and Cell Analysis core, and data were analyzed using FlowJo software. Enriched NK cells were identified by gating on NK1.1hi CD49bhi CD3εlo cells.

In vitro cytokine secretion and flow cytometry

B16 or B16MRD tumor cells cocultured with isolated NK cells were seeded in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin containing anti–PD-1 (catalog no. BE0146; Bio X Cell), anti–PD-L1 (catalog no. BE0101; Bio X Cell), anti-CTLA4 (100 ng/mL; catalog no. BE0164; Bio X Cell), or isotype control (Chrome Pure anti-rabbit IgG; catalog no. 011-000-003; The Jackson Laboratory). Seventy-two hours postincubation, supernatants were harvested and analyzed for cytokine secretion using ELISAs for IFNγ and TFNα. Tumor cells were stained for CD45-PerCP (BD Bioscience) and PD-L1-APC (BioLegend). Flow cytometry analysis was performed as discussed.

Phase-contrast microscopy

Pictures of B16 or B16MRD cell cultures, under the conditions described in the text, were acquired using an Olympus-IX70 microscope (UplanF1 4x/0.13PhL), a SPOT Insight-1810 digital camera and SPOT Software v4.6.

Histopathology

Skin at the site of initial tumor cell injection or tumors was harvested, fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Two independent pathologists, blinded to the experimental design, examined H&E sections for the presence of B16 melanoma cells and immune infiltrates.

Statistical analysis

In vivo experimental data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software). Survival data from the animal studies were analyzed using the log-rank test and the Mann–Whitney U test, and data were assessed using Kaplan–Meier plots. One-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVAs were applied for in vitro assays as appropriate. Statistical significance was determined at the level of P < 0.05.

Results

Model of MRD

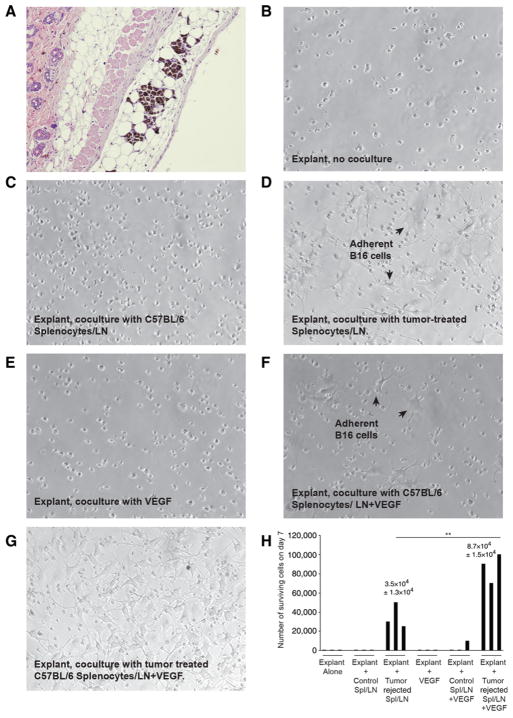

We have previously shown that established subcutaneous B16 tumors can be treated with either prodrug chemotherapy, oncolytic viro-immunotherapy, or adoptive T-cell therapy (21, 34, 36, 43–45). Irrespective of the first-line treatment, histology at the site of initial tumor injection after tumor regression often showed residual melanoma cells in mice scored as tumor free (Fig. 1A). In one experiment, 6 of 10 mice cleared of B16tk tumors by treatment with ganciclovir (using a regimen in which 100% of tumors regressed macroscopically followed by ~50%–80% of the mice undergoing later local recurrence; ref. 43) had histologic evidence of MRD 80 days after tumor seeding. Although parental B16tk cells grow rapidly in tissue culture, no viable B16tk cells were recovered from separate skin explants 75 days following tumor seeding from 15 mice that had undergone complete macroscopic regressions following ganciclovir (Fig. 1B and H). The very low frequency of regrowth of B16 cultures from skin explants was reproducible from mice in which primary B16tk or B16ova tumors were rendered nonpalpable by oncolytic virotherapy with either reovirus (36), adoptive T-cell therapy with Pmel (34), or OT-I T cells (see Table 1 for cumulative summary; ref. 21).

Figure 1.

Model of minimal residual disease. A–G, Histologic sections. A, Skin at the site of B16 cell injection from a C57BL/6 mouse treated with Pmel adoptive T-cell therapy with VSV-gp100 viro-immunotherapy (34). B–D, Skin explants from the site of B16tk cell injection from mice treated with ganciclovir (no palpable tumor after regression) were left untreated (B), cocultured with 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from normal C57BL/6 mice (C), or cocultured with 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice cleared of B16tk tumors after ganciclovir treatment (D). Seven days later, wells were inspected for actively growing tumor cells. Images are representative of nine independent experiments with explants from different primary treatments. E–H, Skin from the sites of cleared B16tk tumors were explanted and treated as in B and were cocultured with VEGF (E; 12 ng/mL), VEGF and 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from normal C57BL/6 mice (F), or VEGF and 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice cleared of B16tk tumors after ganciclovir treatment (G). Three separate explants per treatment were counted. H, Quantitation of B–G.

Table 1.

Tumor outgrowth mediated by activated immune cells

| Culture conditions | Rate of outgrowth >104 cells on d7 |

|---|---|

| Explant alone | 2/19 |

| Explant + Control Spl/LN | 0/7 |

| Explant + Tumor rejected Spl/LN | 4/6 |

| Explant + VEGF | 0/4 |

| Explant + Control Spl/LN + VEGF | 2/5 |

| Explant + Tumor rejected Spl/LN + VEGF | 4/4 |

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

MRD explants from any of 4 different primary treatments.

When C57BL/6 splenocytes from tumor- naïve mice were cocultured with skin explants containing MRD B16 cells, no tumor cells were recovered after in vitro culture (Fig. 1C and H). However, when splenocyte and lymph node cells from mice that had previously cleared B16 tumors were cocultured with skin explants, actively proliferating B16 cultures could be recovered in vitro (Fig. 1D and H). These data suggest that splenocyte and lymph node cells from mice previously vaccinated against primary tumor cells secrete a factor that promotes growth of MRD B16 cells. In this respect, systemic VEGF can prematurely induce early recurrence of B16 MRD following first-line therapy that cleared the tumors (43). Although in vitro treatment of MRD B16 explants with VEGF did not support outgrowth of B16 cells (Fig. 1E and H), coculture of splenocytes and lymph nodes from control nontumor-bearing mice with VEGF supported outgrowth at low frequencies (Fig. 1F and H). However, coculture of splenocytes and lymph nodes from mice that cleared B16 primary tumors with VEGF consistently supported outgrowth of MRD B16 cells with high efficiency (Fig. 1G).

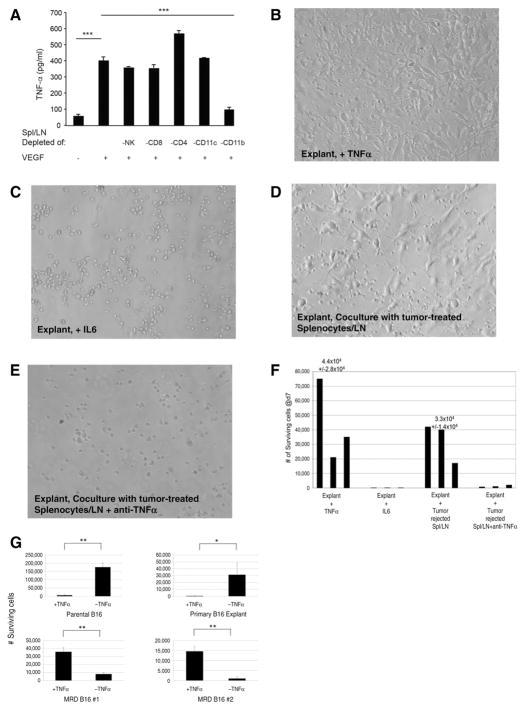

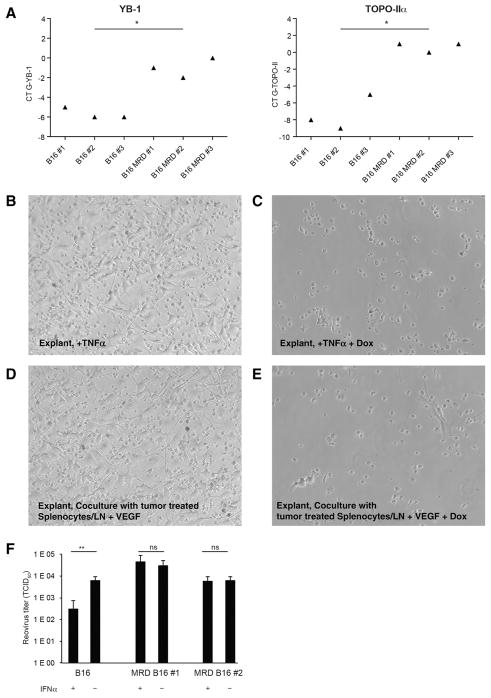

TNFα supports outgrowth of MRD

VEGF-treated splenocyte and lymph node cells from mice that cleared B16 tumors showed rapid upregulation of TNFα, derived principally from CD11b+ cells (Fig. 2A). Depletion of CD4+ T cells enhanced TNFα production from VEGF-treated splenocyte and lymph node cells (Fig. 2A). Outgrowth of MRD B16 cells from skin explants following different first-line therapies was actively promoted by TNFα (Fig. 2B and F) but not by IL6 (Fig. 2C and F) or other cytokines such as IFNγ (Fig. 2B–F). Antibody-mediated blockade of TNFα significantly inhibited the ability of splenocyte and lymph node cells from mice that cleared B16 tumors to support outgrowth of MRD B16 cells (Fig. 2D–F). In contrast to the growth-promoting effects of TNFα on MRD B16 cells, culture of parental B16 cells with TNFα significantly inhibited growth (Fig. 2G). Consistent with Fig. 2A, monocytes and macrophages were the principal source of the growth-promoting TNFα in VEGF-treated splenocyte and lymph node cells from mice that cleared B16 tumors (Fig. 2G). Similarly, outgrowth of MRD TC2 murine prostate cells following first-line viro-immunotherapy was also actively promoted by TNFα, whereas TNFα was highly cytotoxic to the parental tumor cells (Fig. 2I). Therefore, in two different cell types, TNFα changes from an antitumor effector against primary tumors into a growth promoter for MRD. B16 MRD cultures maintained in TNFα for up to 6 weeks retained their dependence upon the cytokine for continued in vitro proliferation. Withdrawal of TNFα did not induce cell death but prevented continued proliferation. Finally, we did not observe reversion to a phenotype in which TNFα was growth inhibitory within a 6-week period.

Figure 2.

MRD cells use TNFα as a growth factor. A, A total of 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice cleared of B16tk tumors (after ganciclovir) were depleted of asialo GM-1+(NKs), CD4+, CD8+, CD11c+, or CD11b+cells by magnetic bead depletion and plated in the presence or absence of VEGF165 (12 ng/mL) in triplicate. Cell supernatants were assayed for TNFα by ELISA after 48 hours. Mean and SD of triplicate wells are shown. Representative of two separate experiments.***, P < 0.0001 (t test). B and C, Skin from the B16tk cell injection site from mice treated with ganciclovir (no palpable tumor after regression) was treated with TNFα (B; 100 ng/mL) or IL6 (C; 100 pg/mL). Seven days later, wells were inspected for actively growing tumor cell cultures. Images are representative of 15 skin explants over five different experiments. D and E, Skin explants from the site of B16tk cell injection of mice treated with ganciclovir (no palpable tumor) cocultured with 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice cleared of B16tk tumors after ganciclovir treatment alone (D) or in the presence of anti-TNFα (E; 0.4 μg/mL). Seven days later, wells were inspected for actively growing tumor cells. Images are representative of 5 separate explants. F, Quantitation of B–E. Three separate explants per treatment were counted. G, A total of 104 parental B16 cells, explanted B16 cells from a PBS-treated mouse, or cells from two MRD B16 cultures (expanded in vitro in TNFα for 72 hours) were plated in triplicate and grown in the presence or absence of TNFα for 4 days. Surviving cells were counted. Mean and SD of triplicates are shown. Representative of three experiments. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 (ANOVA). H, Splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice cleared of B16tk tumors after ganciclovir treatment were treated with no antibody or with depleting antibodies specific for CD8, CD4, asialo GM-1 (NK cells), monocytes and macrophages, or neutrophils. Skin samples from regressed tumor sites were cocultured with 105 depleted or nondepleted splenocytes and lymph node cultures in the presence of VEGF165 (12 ng/mL). Seven days later, wells were inspected for actively growing tumor cell cultures. The percentage of cultures positive for active MRD growth (wells contained >104 adherent B16 cells) is shown. I, A total of 104 explanted TC2 tumor cells from a PBS-treated mouse or cells from two MRD TC2 cultures (expanded in vitro in TNFα for 72 hours) were plated in triplicate and grown in the presence or absence of TNFα for 4 days. Surviving cells were counted. Mean and SD of triplicates are shown. *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001 (ANOVA).

We did not observe any reduction in the ability of cultures to support outgrowth of MRD cells when depleted of neutrophils, CD4 cells, or NK cells, whereas depletion of Ly6G+ cells (completely) and CD8+ T cells (partially) inhibited outgrowth (Fig. 2H). Therefore, taken together with the dependence of TNFα αproduction on CD11b+ cells, our data suggest that CD11b+ monocytes and macrophages are the principal cell type responsible for the TNFα-mediated outgrowth of B16 MRD recurrences, although CD8+ T cells also play a role.

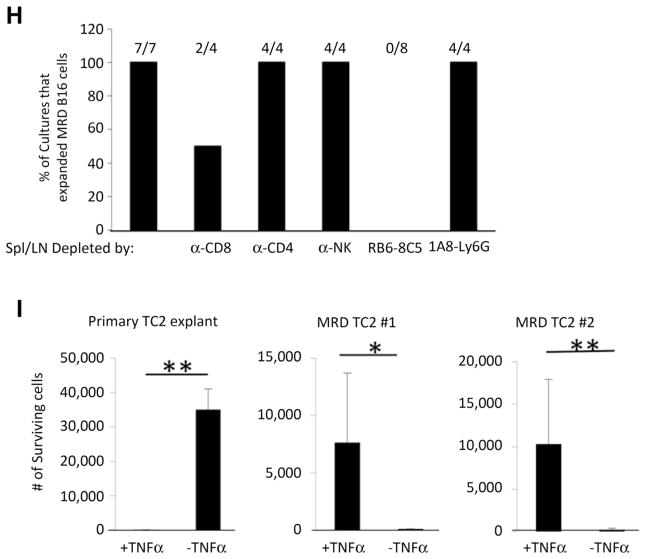

TNFα-expanded MRD acquires a recurrence-competent phenotype

The recurrence-competent phenotype (RCP) of B16 cells emerging from a state of MRD is associated with transient high expression of topoisomerase IIα (TOPO-IIα) and YB-1 (44) and acquired insensitivity to innate immunosurveillance (43). Therefore, we investigated whether the B16 MRD cultures, which we could induce with TNFα, resembled this same phenotype to validate their identity as recurrent tumors. MRD B16 cells expanded in vitro with TNFα overexpressed both Topo-IIα and YB-1 compared with parental B16, consistent with their acquisition of the RCP (Fig. 3A). Coculture of skin explants with TNFα or splenocyte and lymph node cultures induced outgrowth of MRD B16 cells (Fig. 3B and D), which were sensitive to the Topo-IIα–targeting drug doxorubicin (Fig. 3C and E). MRD B16 cells expanded in TNFα were also insensitive to the antiviral protective effects of IFNα upon infection with reovirus and supported more vigorous replication of reovirus than parental B16 cells (Fig. 3F), consistent with acquisition of the RCP (43). In contrast, IFNα protected parental B16 cells from virus replication.

Figure 3.

TNFα-expanded MRD cells acquire the recurrence-competent phenotype. A, A total of 5 × 104 B16 cells or MRD B16 cells (expanded from a site of tumor injection for 72 hours in TNFα) were plated in triplicate. Twenty-four hours later, cDNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR for expression of YB-1 or TOPO-IIα. Relative quantities of mRNA were determined. *, P < 0.05; mean of the triplicate is shown. Representative of two separate experiments with two different B16 MRD recurrences. B–E, Skin explant from theB16tk cell injection site from mice treated with ganciclovir was plated with TNFα (B; 100 ng/mL), TNFα plus doxorubicin (C; 0.1 mg/mL), or cocultured with VEGF and 105 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice cleared of B16tk tumors after ganciclovir treatment without (D) or with doxorubicin (E). Seven days later, wells were inspected for actively growing tumor cells. Representative of three B16 MRD explants. F, A total of 103 B16 cells or MRD B16 cells (expanded from a site of tumor injection for 72 hours in TNFα) were plated in triplicate. Cells were infected with reovirus (MOI 1.0) in the presence or absence of IFNα (100 U) for 48 hours and titers of reovirus determined. Mean and SD of triplicates are shown, **, P < 0.001 (ANOVA).

MRD cells lose sensitivity to NK immunosurveillance

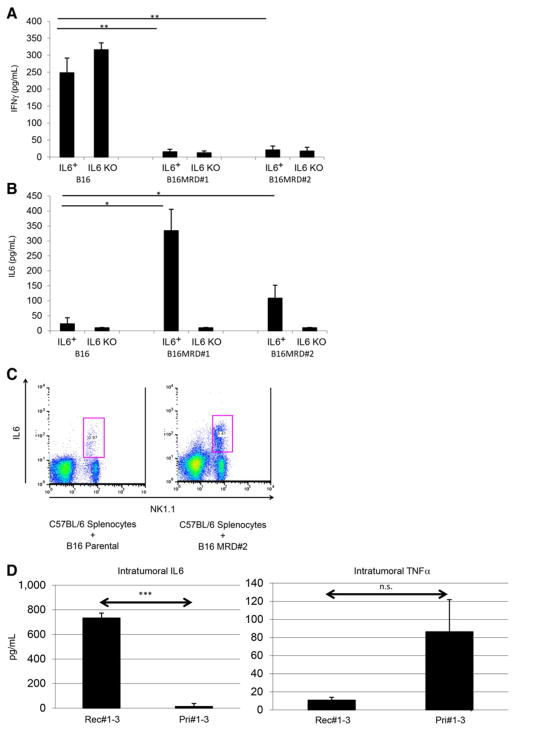

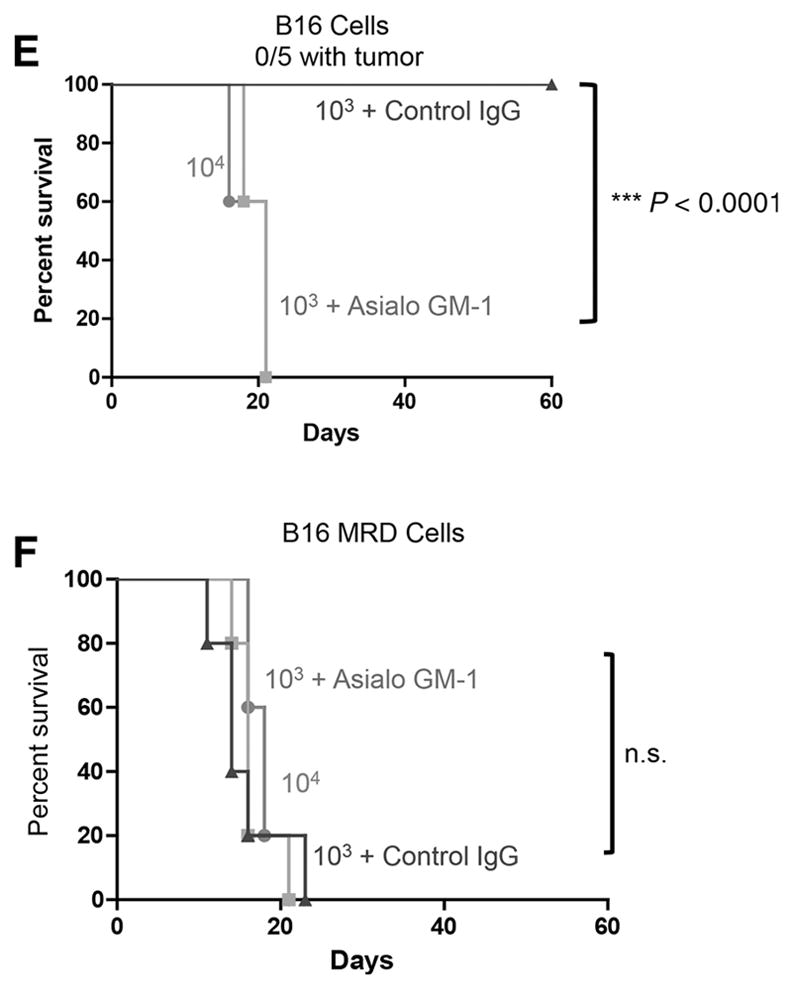

The RCP is also associated with an acquisition of an insensitivity to innate immune effectors (44). Therefore, we next investigated whether NK cells, a major effector of innate immunosurveillance of tumors, differentially recognized primary B16 compared with their B16 MRD derivatives. For the following experiments, a homogenous population of untouched splenic NK1.1hi CD49bhi CD3εlo NK cells was isolated from spleens of C57BL/6 mice. Although purified NK cells secreted significant amounts of IFNγ upon coculture with parental B16 cells, TNFα-expanded MRD B16 cultures did not stimulate IFNγ from NK cells (Fig. 4A). Consistent with reports of a spike in serum IL6 just prior to the emergence of tumor recurrences (43), cocultures of purified NK cells from wild-type mice, but not from IL6 knockout mice, produced IL6 in response to MRD B16 but not parental B16 cells (Fig. 4B). Intracellular staining confirmed that an NK1.1+ cell population within wild-type splenocytes differentially recognized parental B16 and B16 MRD cells through IL6 expression (Fig. 4C). IL6 was detected in excised small recurrent tumors but not in small primary tumors, whereas TNFα could not be detected in recurrent tumors but was present at very low amounts in some primary tumors (Fig. 4D). Although subcutaneous injection of 103 MRD B16 cells generated tumors in 100% of mice, a similar dose of parental B16 cells did not generate tumors in any of the 5 animals (Fig. 4E and F). However, when mice were depleted of NK cells prior to tumor challenge, 103 parental B16 cells became tumor-igenic in 100% of the animals (Fig. 4E). NK-cell depletion had no effect on the already high tumorigenicity of the same dose of MRD B16 cells (Fig. 4F). Therefore, MRD B16 cells expanded in TNFα were significantly more tumorigenic than parental B16 cells, in part, because they were insensitive to NK-cell recognition.

Figure 4.

Parental and MRD cells are differentially recognized by NK cells. B16 or MRD B16 cells (105/well) were cocultured in triplicate with purified NK cells from either wild-type C57BL/6 (IL6+) or IL6 KO mice at an effector:target ratio of 20:1. Seventy-two hours later, supernatants were assayed for IFNγ (A) or IL6 (B) by ELISA. Mean and SD of triplicates are shown, *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 (ANOVA). Representative of three separate experiments. C, Splenocytes and lymph node cells from wild-type C57BL/6 mice were plated with B16 or B16 MRD #2 cells and grown for 72 hours in TNFα at an effector:target ratio of 50:1. Seventy-two hours later, cells were harvested and analyzed for expression of NK1.1 and IL6. D, Three small primary B16ova tumors (<0.3 cm diameter, Pri#1-3) from PBS-treated C57BL/6 mice or three small recurrent B16ova tumors from mice were excised, dissociated, and plated in 24-well plates overnight and then supernatants were assayed for IL6 and TNFα by ELISA. Mean and SD of triplicates are shown; ***, P < 0.0001, for IL6 between primary and recurrent tumors (T-test). E and F, C57BL/6 mice (n = 5 mice/group) were challenged subcutaneously with parental B16ova cells (E) or B16ova MRD cells (F; expanded from a regressed B16ova tumor site for 72 hours in TNFα) at doses of 103 or 104 cells per injection. Included in E and F is a group of mice depleted of NK cells using anti-asialo GM-1 and challenged with 103 B16 or B16 MRD cells. Representative of two separate experiments. Survival analysis was conducted using log-rank tests. The threshold for significance was determined by using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Differential recognition of primary and MRD cells by NK cells

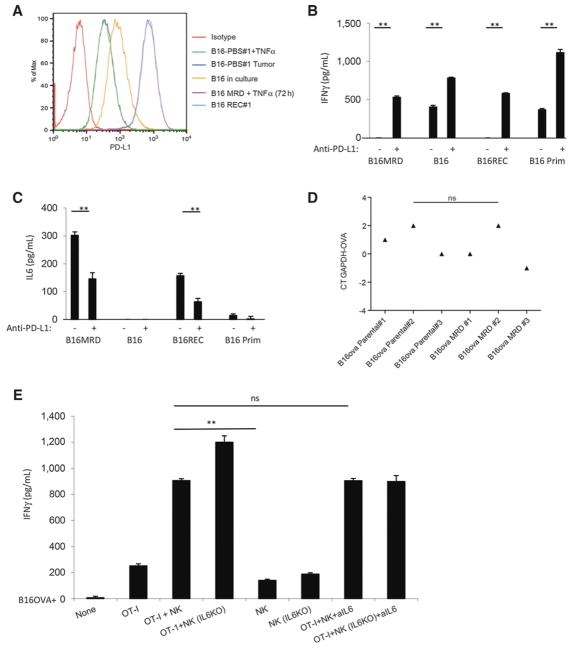

Both MRD B16 cells expanded in TNFα and a freshly resected tumor upregulated the T-cell checkpoint inhibitory molecule PD-L1 (48, 49), whereas PD-L1 expression was low on parental B16 cells and lower on a freshly resected primary tumor, whether or not it was treated with TNFα (Fig. 5A). Although purified NK cells did not secrete IFNγ in response to TNFα-expanded MRD B16 cells or to early recurrent B16 tumor explants (Fig. 4A), they did produce IFNγ in the presence of parental B16 cells and primary B16 tumors (Fig. 5B). Blockade of PD-L1 on MRD B16 cells increased NK cell–mediated IFNγ secretion and also significantly enhanced NK-cell response to parental B16 cells (Fig. 5B). Conversely, NK cell–mediated IL6 secretion in response to MRD B16 cells was significantly decreased by blockade of PD-L1 (Fig. 5C). However, PD-L1 blockade did not alter the inability of parental B16 cells to stimulate IL6 secretion from purified NK cells (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

PD-L1 expression on MRD inhibits immunosurveillance through IL6. A, Expression of PD-L1 was analyzed by flow cytometry on parental B16 cells in culture. Cells from a small (~0.3 cm diameter) B16tk tumor explanted from a PBS-treated mouse were cultured for 72 hours in vitro alone (B16-PBS#1; dark blue) or with TNFα (B16-PBS#1 + TNFα; green). B16 MRD cells recovered from the site of B16tk cell injection after regression were treated with TNFα for 72 hours (B16 MRD + TNFα 72 hours; purple). Cells from a small recurrent B16tk tumor (~0.3 cm diameter) explanted following regression after ganciclovir treatment was cultured for 72 hours without TNFα (B16 REC#1; light blue). Representative of three separate experiments. B and C, MRD B16 cells expanded for 72 hours in TNFα, parental B16 cells, explanted B16tk recurrent tumor cells, or explanted primary B16 tumors were plated (104 cells/well). Twenty-four hours later, 105 purified NK cells from C57BL/6 mice were added to the wells with control IgG or anti–PD-L1. Forty-eight hours later, supernatants were assayed for IFNγ (B) or IL6 (C) by ELISA. Means of triplicates per treatment are shown. Representative of three separate experiments (ANOVA). D, cDNA from three explants of PBS-treated B16ova primary tumors (~0.3 cm diameter) and three MRD B16ova cultures (derived from skin explants after regression with OT-I T-cell therapy and growth for 72 hours in TNFα) were screened by qRT-PCR for expression the ova gene. Relative quantities of ova mRNA were determined (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all experiments. E and F, A total of 104 parental B16ova cells (E) or MRD B16ova cells (F; derived as previously stated) were cocultured with purified CD8+ OT-I T cells and/or purified NK cells from either wild-type C57BL/6 or from IL6 KO mice (OT-I:NK:tumor 10:1:1) in triplicate in the presence or absence of anti-IL6. Seventy-two hours later, supernatants were assayed for IFNγ by ELISA. Mean and SD of the triplicates are shown. Representative of three separate experiments. **, P < 0.01 (ANOVA). G, A total of 104 B16ova MRD cells (derived as already described) were cultured in triplicates, as in F. Seventy-two hours later, cells were harvested and analyzed for intracellular IFNγ. H, After 7 days of coculture, cDNA was screened by qRT-PCR for expression of the ova gene. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 (ANOVA); mean of each treatment is shown.

NK cell–mediated IL6 inhibits T-cell recognition of MRD

MRD B16ova cells recovered from skin explants of B16ova primary tumors rendered to a state of MRD by adoptive OT-I T-cell therapy (21) still retained high expression of the target OVA antigen, suggesting that antigen loss is a later event in the progression to recurrent tumor growth (Fig. 5D). As expected, OT-I T cells secreted IFNγ upon coculture with B16ova cells in vitro, which was augmented by coculture with NK cells from either wild-type or IL6 KO mice (Fig. 5E). Anti-IL6 had no effect on OT-I recognition of parental B16ova cells irrespective of the source of the NK cells (Fig. 5E). Although TNFα-expanded MRD B16ova cells still expressed OVA (Fig. 5D), they elicited significantly lower IFNγ from OT-I and NK cells alone (Fig. 5F). Coculture of OT-I T cells with wild-type, but not with IL6 KO, NK cells abolished IFNγ production in response to MRD B16ova cells (Fig. 5F and G) and was reversed by IL6 blockade (Fig. 5F). After 7 days of coculture with OT-I and NK cells, surviving parental B16ova cells had lost OVA expression, irrespective of IL6 presence (Fig. 5H). However, only in the presence of IL6 blockade did MRD B16ova cells rapidly lose OVA expression (Fig. 5G). These data suggest that NK-mediated IL6 expression in response to TNFα-expanded MRD cells can inhibit T-cell recognition of its cognate antigen expressed by tumor targets and, thereby, slow the evolution of antigen loss variants.

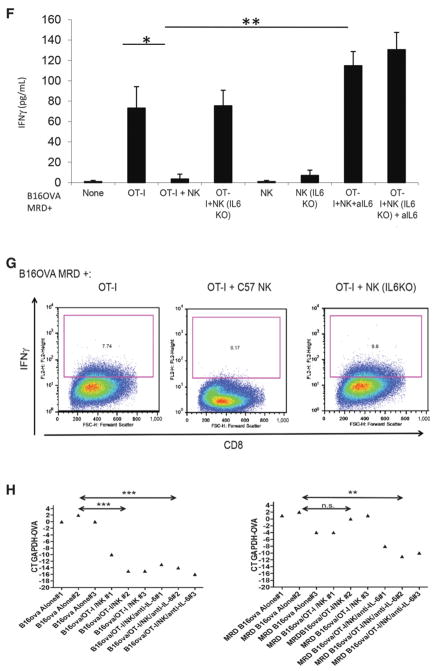

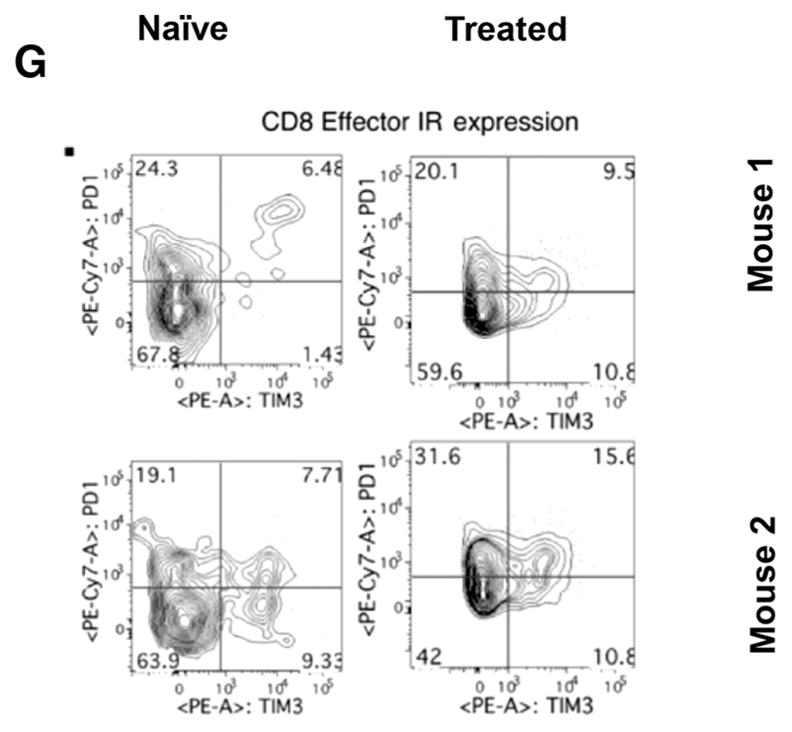

Phenotypic analysis of the lymphoid cells from tumor- naïve mice compared with those from mice cleared of tumor showed minimal differences in subsets of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6A–D). In addition to a nonsignificant trend toward an increase in circulating CD8+ effector cells (CD44hi CD62Llo) in mice cleared of tumor (Fig. 6E), effector cells expressing both inhibitory receptors PD-1 and TIM-3 were also consistently higher compared with tumor- naïve mice (Fig. 6F). These data suggest that mice with tumors that have been treated successfully through immunotherapeutic first-line treatments contain populations of antitumor effector cells that may be functionally impaired to some degree due to elevated expression of checkpoint inhibitor molecules.

Figure 6.

Phenotyping of T cells. Circulating lymphocytes from a tumor-naïve C57BL/6 mice (left column) were compared with those from C57BL/6 mice treated and cleared of B16 primary tumors (right column) (n = 2 mice/group, representative of four independent experiments). Multiparametric flow cytometry for live CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (A), the fraction of CD4+ or CD8+ cells that are CD62Lhi or effector (CD62Llo CD44hi) phenotype (B and E), the fraction of CD62Lhi CD4+ or CD8+ cells expressing the inhibitory receptors (IR) PD-1 and TIM-3, the fraction of CD62Llo CD44hi effector cells expressing the IRs PD-1 and TIM-3 (D and G). To analyze quantitative flow cytometry data, one-way ANOVA testing was conducted with a Tukey posttest; P values reported from these analyses were corrected to account for multiple comparisons.

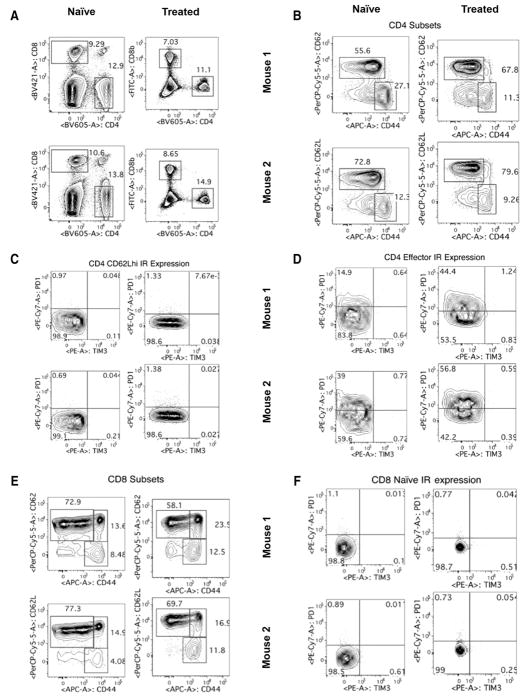

Inhibition of tumor recurrence

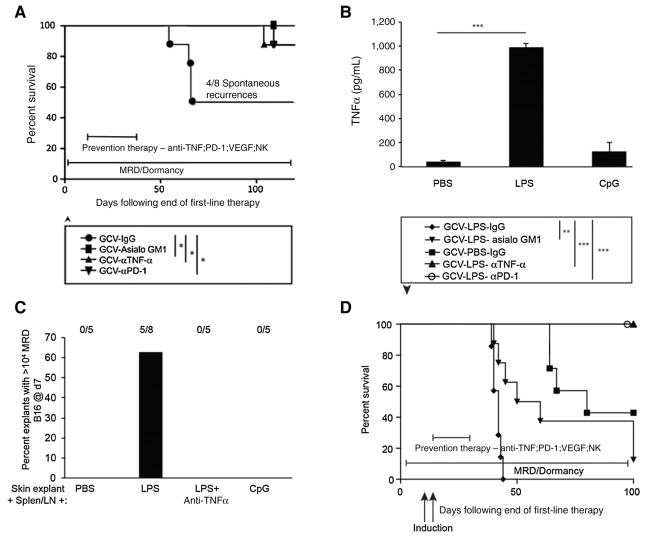

On the basis of these data, several molecules and cells, VEGF, CD11b+ cells, TNFα, PD-L1, NK cells, would be predicted to play an important role in mediating the successful transition from MRD to actively expanding recurrence. After primary B16tk tumors had regressed following chemotherapy with ganciclovir (43), about half of the mice routinely developed recurrences between 40 and 80 days following complete macroscopic regression of the primary tumor (Fig. 7A). However, long-term treatment with antibody-mediated blockade of either PD-1 or TNFα effectively slowed or prevented recurrence (Fig. 7A). The depletion of NK cells also prevented recurrence of B16tk tumors (Fig. 7A), consistent with their secretion of T-cell inhibitory IL6.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of tumor recurrence in vivo. A, Five-day established subcutaneous B16tk tumors were treated with ganciclovir intraperitoneally on days 6 to 10 and 13 to 17. On day 27, mice with no palpable tumors were treated with control IgG, anti-asialo GM-1 (NK depleting), anti-TNFα, or anti–PD-1 every other day for 3 weeks and survival was assessed. Survival analysis was conducted using log-rank tests. The threshold for significance was determined by using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Mice that developed a recurrent tumor were euthanized when the tumor reached a diameter of 1.0 cm. Eight mice per group, except for the ganciclovir/anti-asialo GM-1 group n = 9. *, P < 0.01 Representative of two separate experiments. B, Triplicate cultures of 106 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice were incubated with PBS, LPS (25 ng/mL), or CpG for 48 hours, and supernatants were assayed for TNFα by ELISA. Mean and SD of triplicates are shown; ***, P < 0.0001 PBS versus LPS (t test). C, Cumulative results from skin explants at the sites of tumor from tumor-regressed mice treated with ganciclovir (B16tk tumors), reovirus therapy (B16tk cells), or OT-I adoptive T-cell therapy (B16ova cells). Explants were cocultured with 106 splenocytes and lymph node cells from C57BL/6 mice in the presence of PBS, LPS, CpG, or LPS plus anti-TNFα (0.4 μg/mL). Seven days later, adherent B16 tumor cells were counted and wells containing >104 cells were scored for active growth of MRD cells. P < 0.001 LPS versus all other groups (ANOVA). D, Five-day established subcutaneous B16tk were treated with ganciclovir intraperitoneally on days 6 to 10 and 13 to 17. On days 27 and 29, mice with no palpable tumors were treated with LPS (25 μg/injection). Mice were treated in-parallel with control IgG, anti-asialo GM-1, anti-TNFα, or anti-PD-1 every other day for 3 weeks. Mice with recurrent tumors were euthanized when the tumors reached a diameter of 1.0 cm. Survival of mice with time is shown. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Survival analysis was conducted using log-rank tests. The threshold for significance was determined by using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Representative of two experiments.

Our data would also predict that systemic triggers that induce VEGF (43) and/or TNFα from host CD11b+ cells would accelerate tumor recurrence. In vitro, LPS stimulation of splenocyte and lymph node cultures induced high TNFα (Fig. 7B) and also supported the outgrowth of 5/8 MRD B16 skin explants, an effect that was eradicated by blockade of TNFα (Fig. 7C). Therefore, we tested systemic treatment with TNFα-inducing LPS as a mimic of a trauma or infection that may induce recurrence. Primary tumors that macroscopically regressed into a state of MRD were prematurely induced to recur in 100% of mice following treatment with LPS, consistent with an LPS/TNFα–induced mechanism of induction of recurrence from a state of MRD (Fig. 7D). Under these conditions, depletion of NK cells significantly delayed recurrence but did not prevent it (Fig. 7D), unlike in the model of spontaneous recurrence (Fig. 7A). Prolonged treatment with antibody-mediated blockade of either PD-1 or TNFα successfully prevented long-term recurrence, even when mice were treated with LPS (in 100% of mice in the experiment of Fig. 7D, and in 7/8 mice in a second experiment).

Discussion

We have developed models in which several different first-line therapies reduced established primary tumors to a state of MRD with no remaining palpable tumor (43–45). However, in a proportion of mice in this study, first-line therapy was insufficient to eradicate all tumor cells, leaving histologically detectable disease. Explants of skin at the site of tumor cell injection following regression rarely yielded actively proliferating B16 cells, even though >50% of samples contained residual tumor cells. The frequency with which cultures of MRD cells were recovered following explant was significantly increased by coculture with splenocytes and lymph node cells from mice previously treated for tumors, and this effect was enhanced by VEGF, which induced TNFα from CD11b+ cells. Taken together, we believe that CD11b+ monocytes and macrophages are the principal cell type responsible for the VEGF-mediated induction of TNFα and for the TNFα-mediated outgrowth of B16 MRD recurrences. Although we showed TNFα was highly cytotoxic to parental B16 cells and primary tumor explants, TNFα supported expansion of MRD cells from skin explants at high frequency, irrespective of the primary treatment. As shown previously, splenocytes from mice with cleared B16 tumors after ganciclovir treatment killed significantly higher numbers of target B16 cells in vitro than did splenocytes from control, tumor- naïve mice, confirming the generation of an effective antitumor T-cell response (42). In contrast, here, we show no significant difference between killing of B16MRD cells expanded for 120 hours in TNFα in vitro by splenocytes from mice that cleared a B16 tumor compared with splenocytes from control, tumor- naïve mice. We are currently investigating the molecular mechanisms by which B16MRD cells effectively evade the antitumor T-cell responses induced by first-line treatment (such as ganciclovir, T-cell therapy, or oncolytic virotherapy).

TNFα-mediated expansion of MRD B16 cells induced the RCP (43, 44), shown by de novo expression of recurrence-associated genes (YB-1 and topoisomerase IIα; ref. 44). Reactivation of metastatic cells lying latent in the lungs has been associated with expression of the Zeb1 transcription factor, which mediates the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (50). NK cells are major innate effectors of immunosurveillance of tumors and responded differently to recurrent competent MRD B16 cells compared with primary B16 cells. We show NK cells were activated by parental B16 cells to secrete IFNγ and were major effectors of in vivo tumor clearance. In contrast, TNFα-expanded MRD B16 cells induced NK cells to secrete IL6 instead of IFNγ, which was not seen for parental B16 cells, effects mediated, in part, through PD-L1. IL6 produced by NK cells in response to TNFα-expanded MRD B16ova cells also inhibited OT-I T-cell recognition of OVA+ tumor targets. TNFα-expanded MRD cells still retained OVA expression, despite using first-line OVA-targeted T-cell therapy. Only upon prolonged coculture of OVA+ MRD cells with OT-I+ NK cells with IL6 blockade was significant antigen loss observed, consistent with the long-term, but not early, loss of OVA antigen expression from B16ova recurrences following OT-I adoptive T-cell therapy (21, 43). Therefore, antigen loss in MRD cells is not an essential prerequisite for the emergence of tumor recurrences (21) and may occur through powerful selective pressure on very early antigen-positive recurrent tumors as they expand in vivo in the presence of ongoing antigen-targeted T-cell pressure.

Our data here are consistent with a model in which the transition from quiescent MRD to actively expanding recurrence is promoted by the acquisition of a phenotype in which TNFα changes from being a cytotoxic growth inhibitor (against primary tumors), to promoting the survival and growth of one, or a few, MRD cells. It is not clear whether these TNFα-responsive clones exist within the primary tumor population, perhaps as recurrence-competent stem cells (31), or whether this RCP is acquired by ongoing mutation during the response to first-line therapy (9, 14, 29, 30). As established primary B16 and B16 MRD tumors both have low intratumoral NK infiltration, we hypothesize that the differential recognition of B16 or B16 MRD cells by NK cells occurs at very early stages of tumor development. Therefore, it may be that different subsets of NK cells mediate the differential recognition of primary B16 (rejection) or B16 MRD (growth stimulation). However, in our experiments here, a homogenous population of untouched splenic NK1.1hi CD49bhi CD3εlo NK cells differentially recognized parental B16 and B16 MRD cells, suggesting that the basis for these different NK responses are, in large part, due to tumor–cell intrinsic properties. These recurrence-competent MRD cells are insensitive to both innate and adaptive immunosurveillance mechanisms, in part, through expression of PD-L1. With respect to escape from adaptive immunosurveillance, we show both that the MRD cells express high PD-L1 and that the fraction of effector cells expressing both inhibitory receptors PD-1 and TIM-3 was consistently higher in tumor-experienced mice than tumor- naïve mice. Integral to both innate and adaptive immune evasion, TNFα-expanded MRD tumor cells induced an anti-inflammatory profile of IL6hi and IFNγlo expression from NK cells, the opposite of the profile of NK recognition (IL6lo IFNγhi) induced by parental primary tumor cells. This altered role of NK cells as prorecurrence effectors, as opposed to antitumor immune effectors, was due to impaired killing of MRD cells and recurrent tumor cells plus the secretion of IL6. This NK-derived IL6, in turn, inhibited T-cell responses against recurrent tumors, even when they continued to express T cell–specific antigens.

This model showed several molecules and cells, VEGF, CD11b+ cells, TNFα, PD-1/PD-L1, NK cells, can be targeted for therapeutic intervention to delay recurrence. In our model of spontaneous recurrence, depletion of NK cells or antibody-mediated blockade of either TNFα or PD-1 significantly inhibited tumor recurrence following first-line ganciclovir. Our data suggest that a systemic trigger, such as VEGF-induced by trauma or infection, promotes TNFα release from host CD11b+ cells, leading to growth stimulation of MRD cells. Consistent with this, LPS both induced TNFα from splenocytes and lymph node cells and mimicked TNFα in the generation of expanding MRD cultures from skin explants. Recurrence could be induced prematurely by LPS, as a mimic of a systemic infection/trauma, consistent with a report in which LPS treatment reactivated intravenously injected disseminated tumor cells preselected for properties of latency (50). These results suggest that patients in a state of MRD may be at significantly increased risk of recurrence following infections and/or trauma, which induce the release of systemic VEGF and/or TNFα. However, blockade of PD-1 or TNFα following this trauma-like event prevented tumor recurrence. We are currently investigating when, and for how long, these potentially expensive recurrence-blocking therapies will be required to be administered in patients. This is especially relevant for those patients in whom MRD may be present over several years before recurrence is triggered. Transcriptome analysis of MRD and early recurrences, compared with parental tumor cells, is underway in both mouse models (B16 and TC2) as well as in patient samples where matched pairs of primary and treatment failed recurrence tumors are available. These studies will identify the signaling pathways that differ between the cell types to account for their differential responses to TNFα signaling and IFNγ and IL6 production by NK cells. Future studies will focus on identifying which cells become recurrent tumors, the mutational and selective processes involved in the transition, identification of the biological triggers for recurrence (1, 32), and the time over which recurrence-inhibiting therapies must be administered.

In summary, we show here that the transition from MRD to recurrence involves the subversion of normal innate immunosurveillance mechanisms. In particular, TNFα produced in response to pathologic stimuli becomes a prorecurrence, as opposed to antitumor, growth factor. Simultaneously, NK cells, which normally restrict primary tumor growth, fail to kill expanding recurrent tumor cells and produce IL6 that helps to suppress adaptive T-cell responses, even with continued expression of T cell–targetable antigens. Finally, our data show that therapies aimed at blocking certain key molecules (PD-1, TNFα) and cell types (NK cells) may be valuable in preventing this transition from occurring in patients.

Table 2.

TNFα-mediated tumor outgrowth

| Viable cultures of B16 MRD

|

||

|---|---|---|

| First-line therapy inducing MRD | −TNFα | +TNFα |

| B16tk/GCV | 0/7 | 5/5 |

| B16tk/i.t. Reovirus | 1/9 | 4/4 |

| B16ova/OT-I | 0/7 | 5/7 |

| B16tk/Pmel/VSV-hgp100 | 1/4 | 3/3 |

| Total | 2/27 (7%) | 17/19 (89%) |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Toni L. Higgins for expert secretarial assistance.

Grant Support: This work was supported by The European Research Council, The Richard M. Schulze Family Foundation, the Mayo Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the NIH (R01 CA175386 and R01 CA108961), the University of Minnesota and Mayo Clinic Partnership, and a grant from Terry and Judith Paul.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

M. Coffey is the president and chief executive officer at and has ownership interest in Oncolytics Biotech, Inc. A. Melcher is a consultant/advisory board member for Amgen and Bristol-Myers Squibb. No potential confiicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Authors' Contributions: Conception and design: M. Coffey, P. Selby, K. Harrington, R. Vile

Acquisition of data (provided animals, acquired and managed patients, provided facilities, etc.): T. Kottke, K.G. Shim, N. Boisgerault, J. Thompson, R. Vile

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis): T. Kottke, L. Evgin, H. Pandha, K. Harrington, R. Vile, D. Rommelfanger, S. Zaidi, R.M. Diaz

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: L. Evgin, K.G. Shim, E. Ilett, M. Coffey, P. Selby, H. Pandha, K. Harrington, A. Melcher, R. Vile

Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases): P. Selby, R. Vile

Study supervision: J. Thompson, P. Selby, R. Vile

References

- 1.Yeh AC, Ramaswamy S. Mechanisms of cancer cell dormancy–another hallmark of cancer? Cancer Res. 2015;75:5014–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Models, mechanisms and clinical evidence for cancer dormancy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:834–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss PE, Chambers AF. Does tumour dormancy offer a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:871–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hensel JA, Flaig TW, Theodorescu D. Clinical opportunities and challenges in targeting tumour dormancy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGowan PM, Kirstein JM, Chambers AF. Micrometastatic disease and metastatic outgrowth: clinical issues and experimental approaches. Future Oncol. 2009;5:1083–98. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pantel K, Alix-Panabieres C, Riethdorf S. Cancer micrometastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:339–51. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Bragado P, Sosa MS. Metastasis awakening: targeting dormant cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:276–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polzer B, Klein CA. Metastasis awakening: the challenges of targeting minimal residual cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:274–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxevanis CN, Perez SA. Cancer dormancy: a regulatory role for endogenous immunity in establishing and maintaining the tumor dormant state. Vaccines. 2015;3:597–619. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3030597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albini A, Tosetti F, Li VW, Noonan DM, Li WW. Cancer prevention by targeting angiogenesis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:498–509. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almog N, Ma L, Raychowdhury R, Schwager C, Erber R, Short S, et al. Transcriptional switch of dormant tumors to fast-growing angiogenic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2009;69:836–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Indraccolo S, Stievano L, Minuzzo S, Tosello V, Esposito G, Piovan E, et al. Interruption of tumor dormancy by a transient angiogenic burst within the tumor microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4216–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–31. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blatter S, Rottenberg S. Minimal residual disease in cancer therapy–Small things make all the difference. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;21–22:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karrison TG, Ferguson DJ, Meier P. Dormancy of mammary carcinoma after mastectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:80–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs AF, Ghahremani MT, Stefenelli U, Bitter K. Postoperative chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in cancer of the oral cavity and the oropharynx–long-term results. J Chemother. 2003;15:495–502. doi: 10.1179/joc.2003.15.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Retsky MW, Demicheli R, Hrushesky WJ, Baum M, Gukas ID. Dormancy and surgery-driven escape from dormancy help explain some clinical features of breast cancer. Apmis. 2008;116:730–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drake CG, Jaffee EM, Pardoll DM. Mechanisms of immune evasion by tumors. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:51–81. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrido F, Cabrera T, Aptsiauri N. "Hard" and "soft" lesions underlying the HLA class I alterations in cancer cells: implications for immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:249–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberger O, Volovitz I, Machlenkin A, Vadai E, Tzehoval E, Eisenbach L. Exuberated numbers of tumor-specific T cells result in tumor escape. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3450–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaluza KM, Thompson J, Kottke T, Flynn Gilmer HF, Knutson D, Vile R. Adoptive T cell therapy promotes the emergence of genomically altered tumor escape variants. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:844–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu K, Caldwell SA, Greeneltch KM, Yang D, Abrams SI. CTL adoptive immunotherapy concurrently mediates tumor regression and tumor escape. J Immunol. 2006;176:3374–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu VC, Wong LY, Jang T, Shah AH, Park I, Yang X, et al. Tumor evasion of the immune system by converting CD4+CD25- T cells into CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells: role of tumor-derived TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2007;178:2883–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagaraj S, Gupta K, Pisarev V, Kinarsky L, Sherman S, Kang L, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13:828–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Perez L, Kottke T, Diaz RM, Thompson J, Holmen S, Daniels G, et al. Potent selection of antigen loss variants of B16 melanoma following inflammatory killing of melanocytes in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2009–17. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uyttenhove C, Maryanski J, Boon T. Escape of mouse mastocytoma P815 after nearly complete rejection is due to antigen-loss variants rather than immunosuppression. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1040–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.3.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, et al. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16168–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multi-region sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:323–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawson DA, Bhakta NR, Kessenbrock K, Prummel KD, Yu Y, Takai K, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals a stem-cell program in human metastatic breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;526:131–5. doi: 10.1038/nature15260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giancotti FG. Mechanisms governing metastatic dormancy and reactivation. Cell. 2013;155:750–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaluza K, Kottke T, Diaz RM, Rommelfanger D, Thompson J, Vile RG. Adoptive transfer of cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting two different antigens limits antigen loss and tumor escape. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23:1054–64. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rommelfanger DM, Wongthida P, Diaz RM, Kaluza KM, Thompson JM, Kottke TJ, et al. Systemic combination virotherapy for melanoma with tumor antigen-expressing vesicular stomatitis virus and adoptive T-cell transfer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4753–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wongthida P, Diaz RM, Pulido C, Rommelfanger D, Galivo F, Kaluza K, et al. Activating systemic T-cell immunity against self tumor antigens to support oncolytic virotherapy with vesicular stomatitis virus. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22:1343–53. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kottke T, Chester J, Ilett E, Thompson J, Diaz R, Coffey M, et al. Precise scheduling of chemotherapy primes VEGF-producing tumors for successful systemic oncolytic virotherapy. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1802–12. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kottke T, Hall G, Pulido J, Diaz RM, Thompson J, Chong H, et al. Antiangiogenic cancer therapy combined with oncolytic virotherapy leads to regression of established tumors in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1551–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI41431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kottke T, Errington F, Pulido J, Galivo F, Thompson J, Wongthida P, et al. Broad antigenic coverage induced by viral cDNA library-based vaccination cures established tumors. Nat Med. 2011;2011:854–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulido J, Kottke T, Thompson J, Galivo F, Wongthida P, Diaz RM, et al. Using virally expressed melanoma cDNA libraries to identify tumor-associated antigens that cure melanoma. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:337–43. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melcher AA, Todryk S, Hardwick N, Ford M, Jacobson M, Vile RG. Tumor immunogenicity is determined by the mechanism of cell death via induction of heat shock protein expression. Nat Med. 1998;4:581–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Perez L, Gough M, Qiao J, Thanarajasingam U, Kottke T, Ahmed A, et al. Synergy of adoptive T-cell therapy with intratumoral suicide gene therapy is mediated by host NK cells. Gene Ther. 2007;14:998–1009. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vile RG, Castleden SC, Marshall J, Camplejohn R, Upton C, Chong H. Generation of an anti-tumour immune response in a non-immunogenic tumour: HSVtk-killing in vivo stimulates a mononuclear cell infiltrate and a Th1-like profile of intratumoural cytokine expression. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:267–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<267::aid-ijc23>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kottke T, Boisgerault N, Diaz RM, Donnelly O, Rommelfanger-Konkol D, Pulido J, et al. Detecting and targeting tumor relapse by its resistance to innate effectors at early recurrence. Nat Med. 2013;19:1625–31. doi: 10.1038/nm.3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boisgerault N, Kottke T, Pulido J, Thompson J, Diaz RM, Rommelfanger-Konkol D, et al. Functional cloning of recurrence-specific antigens identifies molecular targets to treat tumor relapse. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1507–16. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaidi S, Blanchard M, Shim K, Ilett E, Rajani K, Parrish C, et al. Mutated BRAF emerges as a major effector of recurrence in a murine melanoma model after treatment with immunomodulatory agents. Mol Ther. 2014;23:845–56. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Health WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonistic peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Overwijk W, Theoret M, Finkelstein S, Surman D, de Jong L, Vyth-Dreese F, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Francisco LM, Sage PT, Sharpe AH. The PD-1 pathway in tolerance and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:219–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Cock JM, Shibue T, Dongre A, Keckesova Z, Reinhardt F, Weinberg RA. Inflammation triggers Zeb1-dependent escape from tumor latency. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6778–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]