Keloids are an exaggerated response to cutaneous wound healing. They negatively affect patients’ quality of life, and no treatment is guaranteed to prevent occurrence or recurrence. Previous results from the Genetic Causes of Keloid Formation Study (GCKFS), an IRB-approved keloid registry, showed African-Americans with keloids reported having hypertension and obesity at increased rates compared to the general African-American population.1 We formally tested for any association of keloids with these comorbidities using objective measures.

Seventy-five African-American GCKFS participants with keloids were matched to controls obtained from the Dallas Heart Study (DHS)2 at a 7:1 DHS:GCKFS ratio. Participants were categorized into normotensive or hypertensive and into normal weight or obese cohorts using objectively recorded measurements; calculations were made using Mann–Whitney U-test (significance P < 0.05). Among the GCKFS cohort, subanalyses assessed included number of keloids, location, and number of anatomic sites involved.

The gender ratio as well as the mean, median, and age range were similar between the keloid group (GCKFS) and the control group (DHS). Thirty-four of 75 (45.3%) GCKFS participants were hypertensive compared to 169/525 (32.2%) controls (P = 0.02); 41 (54.7%) GCKFS participants were obese compared to 243 (46.3%) controls (P = 0.11). On subanalyses, the association between keloids and hypertension was still signifi-cant with males (P = 0.03) and with individuals under age 30 (P = 0.04) (Table 1). A total of 500 total keloids were distributed among six designated anatomic sites: ears, neck and superior (excluding ears), extremities, trunk, abdomen, and other. Sub-analyses were assessed among the GCKFS cohort using number of keloids, keloid location, and number of keloid-affected anatomic sites; they showed a significant difference in obesity prevalence between ear-inclusive keloids (ears ± other sites) versus ear-exclusive keloids (anywhere but the ears) (P = 0.04) and a trending difference in obesity prevalence between keloids affecting one or two sites versus >2 sites (P = 0.06) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Hypertension and obesity association with keloids by age

| Ages | HTN

|

Obese

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCKFS/total | DHS/total | P value | GCKFS/total | DHS/total | P value | |

| ≤30 | 2/14 | 1/97 | 0.04* | 6/14 | 30/97 | 0.27 |

| 31–40 | 3/15 | 14/105 | 0.36 | 5/15 | 46/105 | 0.85 |

| 41–50 | 13/24 | 70/168 | 0.17 | 16/24 | 88/168 | 0.13 |

| 51–60 | 12/16 | 66/112 | 0.17 | 10/16 | 60/112 | 0.35 |

| 61+ | 4/6 | 18/43 | 0.24 | 4/6 | 19/43 | 0.29 |

| Total | 34/75 | 169/525 | 0.02* | 41/75 | 243/525 | 0.11 |

indicates statistically significant P value of less than 0.05.

Table 2.

GCKFS hypertension and obesity subanalyses based on keloid location and number

| GCKFS keloid location and number subanalyses | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension P value | Obesity P value | |

| <3 Sites vs. >2 Sites | 0.61 | 0.06 |

| 1 Keloid vs. >1 Keloids | 1 | 0.49 |

| Ear only keloids vs. Trunk only keloids | 0.26 | 1 |

| At least ears vs. No ear keloids | 0.93 | 0.04* |

| At least trunk keloids vs. No trunk keloids | 0.47 | 0.5 |

| Ear only keloids vs. no ear keloids | 0.36 | 0.86 |

| Trunk only keloids vs. No trunk keloids | 0.42 | 1 |

indicates statistically significant P value of less than 0.05.

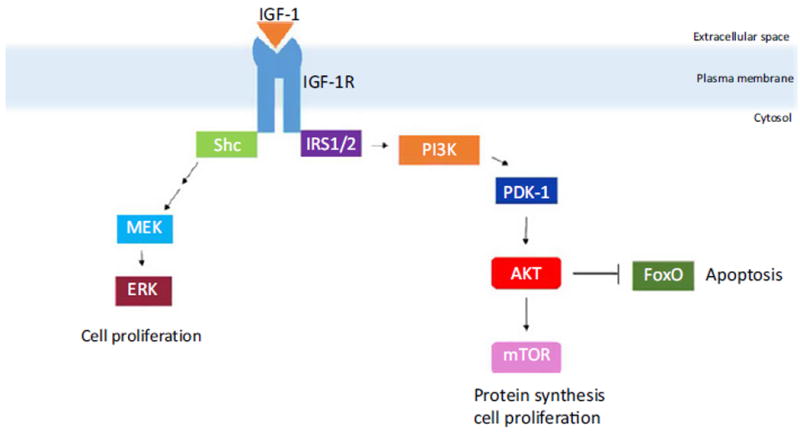

An association between hypertension and keloid formation has been reported in the literature, with hypertension and keloid size/number having a statistically significant positive correlation.3,4 Individuals under age 30 with keloids have a higher incidence of hypertension.5,6 Our results are consistent with previously reported findings and invite further inquiry into the systemic similarities between hypertension and keloid pathogenesis. A significant difference in obesity prevalence was seen between ear-inclusive versus ear-exclusive keloids. This suggests that obesity may play a role in the presence of keloids occurring on the ears. A systemic signaling molecule such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) or leptin may influence obese individuals’ susceptibility to developing keloids. IGF-1 functions as a proliferative and differentiation factor (oftentimes via the MAPK or PI3K signaling pathway) affecting cell survival, protein synthesis, and energy utilization7 (Fig. 1). IGF-1 is also a nutrient sensor, which is modulated by available energy.7 However, little is understood of how precisely IGF-1 upregulates collagen synthesis relative to energy.7 Leptin has been shown to be overexpressed in keloids compared to normal skin; higher leptin levels were associated with positive family history and with axial site involvement.8 From this, leptin overexpression may increase keloid occurrence through modified cytokine production, prolonged healing phase, excessive collagen deposition, and/or delayed collagen degradation. More research is needed to assess these postulations. Limitations of this study include a homogeneous ethnic population and a relatively small cohort size. Future analysis of larger and ethnically distinct cohort sets may confirm our current findings.

Figure 1.

The figure schematically depicts signaling pathways of IGF-1 functioning as a proliferative and differentiation factor. IGF-1 may result in cell proliferation, increased cell survival, and increased protein synthesis, potentially contributing to keloid pathogenesis

Keloids are associated with increased prevalence of hypertension in males and those under age 30. A statistically significant association between obesity and keloids could not be determined overall, but a difference between ear-inclusive versus ear-exclusive keloids was detected from objective measures in this study.

Acknowledgments

Helen Hobbs MD, Jonathan Cohen PhD, Teresa Eversole, Mereeja Varghese (McDermott Center for Human Growth and Development, UT Southwestern Medical Center); Irene Dougherty, An Tran, and Rose Cannon (Department of Dermatology, UT Southwestern Medical Center). This study was supported by the Dedman Family Endowed Program for Scholars in Clinical Care and, the Dermatology Foundation. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23 AR069728, and the UT Southwestern Summer Medical Student Research Program.

References

- 1.Adotama P, Rutherford A, Glass DA. Association of keloids with systemic medical conditions: a retrospective analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;55:38–40. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, et al. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arima J, Huang C, Rosner B, et al. Hypertension: a systemic key to understanding local keloid severity. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:213–221. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa R, Arima J, Ono S, et al. Total management of a severe case of systemic keloids associated with high blood pressure (Hypertension): Clinical symptoms of keloids may be aggravated by hypertension. Eplasty. 2013;13:e25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolery-Lloyd H, Berman B. A controlled cohort study examining the onset of hypertension in black patients with keloids. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:581–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snyder AL, Zmuda J, Thompson P. Keloid associated with hypertension. The. Lancet. 1996;347:465–466. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guntur AR, Rosen CJ. IGF-1 regulation of key signaling pathways in bone. Bonekey Rep. 2013;2:437. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seleit I, Bakry OA, Samaka RM, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of leptin expression in wound healing: a clue to exuberant scar formation. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24:296–306. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]