Abstract

Radiotherapy is one of the major therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment. In the past decade, there has been growing interest in using high Z (atomic number) elements (materials) as radiosensitizers. New strategies in nanomedicine could help to improve cancer diagnosis and therapy at cellular and molecular levels. Metal-based nanoparticles usually exhibit chemical inertness in cellular and subcellular systems and may play a role in radiosensitization and synergistic cell-killing effects for radiation therapy. This review summarizes the efficacy of metal-based NanoEnhancers against cancers in both in vitro and in vivo systems for a range of ionizing radiations including gamma-rays, X-rays, and charged particles. The potential of translating preclinical studies on metal-based nanoparticles-enhanced radiation therapy into clinical practice is also discussed using examples of several metal-based NanoEnhancers (such as CYT-6091, AGuIX, and NBTXR3). Also, a few general examples of theranostic multimetallic nanocomposites are presented, and the related biological mechanisms are discussed.

Keywords: tumor, radiation therapy, metal-based nanoparticles, NanoEnhancers, radiosensitization, synergistic chemo-radiotherapy

Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) is one of the most effective modalities for the treatment of primary and metastatic solid tumors, microscopic tumor extensions, as well as regional lymph nodes. Alone or combined with other modalities, RT is effective at eliminating cancer cells including stem cells 1 and is used in the treatment of more than half of cancer patients. Radiations (X-rays, γ-rays, electrons, neutrons, and charged particles) utilized in RT could damage cells by directly interacting with critical targets or indirectly through free radical production such as hydroxyl radicals 2. The evolving computer-aided and information-based radiotherapy techniques are capable of locally delivering ionizing radiation to the tumor by precise external irradiation or brachytherapy while minimizing normal tissue injury. These techniques include the state-of-the-art 3D-conformal image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT) with in-room imaging, intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with dynamically controlled multileaf collimators (MLCs) and particle therapy (protons and carbon ions) with reverse depth dose profile. The clinical applications of RT can benefit from the technology improvements, but increasing the radiation dose is insufficient to significantly improve tumor control probability (TCP) for many radioresistant tumors. To further widen the therapeutic window, biological and chemical strategies using individual biomarkers to predict, evaluate and manage responsiveness to specific therapies should be properly integrated with the advanced RT techniques 3. Another main challenge of RT is that tumors are often located near normal tissues and organs at risk (OARs), limiting the radiation doses delivered to the target volumes. Therefore, agents preferentially sensitizing tumors to ionizing radiation, termed radiosensitizers, have attracted great interest in radiation oncology 4. Also, radioprotectors, agents that have radioprotective effects, have been employed to reduce normal tissue complication probability (NTCP). Almost all these agents have been developed for interactions with specific biological targets (the pathway/signaling cascade) at levels from molecules to cells to organs to the whole organism, modulating the responses that occur after radiation exposure (Fig. 1). Thus, in the era of precision medicine, new advances in technology and cancer biology will further improve the therapeutic outcome of RT at the individual patient level.

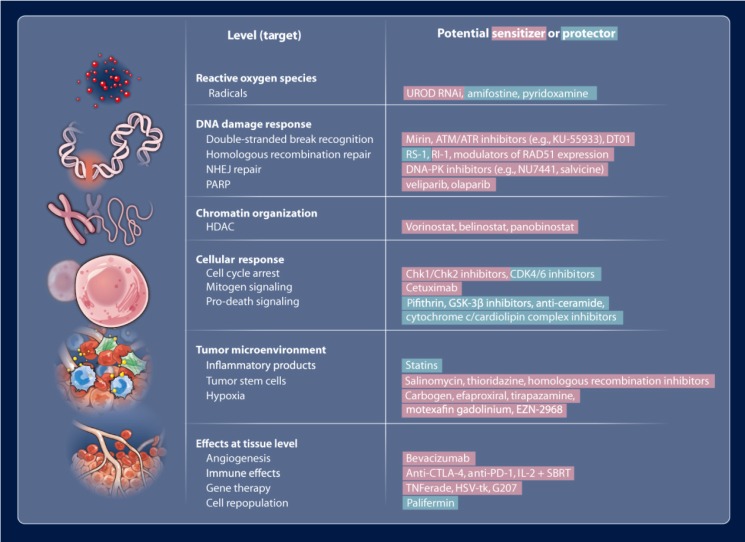

Figure 1.

Potential radiosensitizers (red) and radioprotectors (green) that may be useful in modulating radiation effects. Reproduced with permission from reference 4, copyright 2013 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Nanomedicines can improve therapeutic benefits by reducing systemic side effects and/or increasing drug accumulation inside tumors by using nanomaterials based on organic, inorganic, protein, lipid, glycan compounds, synthetic polymers, and viruses 5. The physicochemical properties (size, shape, coating and functionalization, etc.) of nano-agents influence their pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, biodistribution, as well as targeting and intracellular delivery. The nano-agents can achieve specific tumor targeting via passive targeting utilizing the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect due to the leaky vasculature of cancerous tissues, active targeting (through high-affinity targeting molecules), and stimuli-responsive triggered release to endogenous or exogenous stimuli. However, a variety of real challenges, such as poor biocompatibility and lack of targeting specificity, hamper the development of ideal nanomedicines.

It is of note that high Z (atomic number) materials, especially metals, usually exhibit chemical inertness, which could decrease potential health hazards in cellular and subcellular systems, an attribute that is critical for clinical use 6. Another factor that can help reduce the side effects of nano-agents is local intratumoral or superselective intra-arterial injection and tumor bed deposition during surgery for localized solid tumors, lowering the volume of distribution. In 1980, Matsudaira et al. first demonstrated that iodine contrast medium could sensitize cultured cells to X-rays 7. Subsequently, numerous studies investigating the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of metal-based nanoparticles for radiotherapy, termed “NanoEnhancers”, have been reported in the past decades 8. Photoelectrons and Auger electrons generated from the irradiated metal-based nanoparticles could contribute to the dose enhancement and subsequent radiobiological enhancement 9, 10. The classical radiosensitization processes consist of physical dose enhancement, chemical contribution and biological phase (Fig. 2, lower-left) which cells undergo as the time progresses from nanoseconds to days. Specifically, the electrons, emitted along the primary tracks of the incident ionizing particles, are capable of inducing inner shell ionization of the metal atoms, and the Auger electrons are emitted from the metal-based nanoparticles with the relaxation of the excited core 11. Subsequently, the electrons can damage cells directly through the interactions with critical targets or indirectly through free radical production. Furthermore, adding free radical scavengers such as DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) or NAC (N-acetyl cysteine) in the biological systems would be helpful in evaluating the separate roles for direct and indirect effects in the metal-based NanoEnhancer radiosensitization process. Based on the experimental results, we previously concluded that the production of hydroxyl radical in the radiosensitization processes of metal-based nanoparticles might be attributed to the surface-catalyzed reaction, especially for high-energy charged particles 12-14. Additionally, other pharmacological effects of metal-based nanoparticles cannot be excluded for their radiosensitizing/synergistic effects.

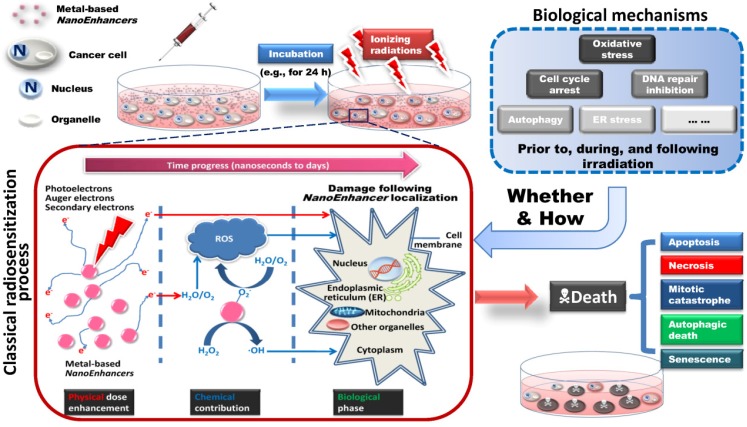

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of metal-based NanoEnhancer radiosensitization process. (Upper-left) Following administration of NanoEnhancers, radiation therapy is carried out after a certain time interval. (Upper-right) Probable biological mechanisms include oxidative stress, cell cycle arrest, DNA repair inhibition, autophagy, ER stress, etc. Besides ionizing radiation-induced fluctuations in biological systems, the metal-based NanoEnhancers internalized by tumor cells can elicit significant cellular biochemical changes prior to, during, and following irradiation. (Lower-left) Classical radiosensitization process, which typically consists of physical dose enhancement, chemical contribution and biological phase, resulting in lethal cellular damage. The primary targets depending on cellular and subcellular distribution and location of metal-based NanoEnhancers include cell membrane, cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and other organelles. Specifically, photoelectrons and Auger electrons generated from the irradiated metal-based nanoparticles could contribute to the dose enhancement directly through the interactions with critical targets or indirectly through free radical production (mostly ROS (reactive oxygen species)), which can be assessed by DCFH-DA (2',7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate) in living cell models and 3-CCA (coumarin-3-carboxylic acid) in aqueous buffered solutions. In addition, the production of hydroxyl radical in the radiosensitization processes of metal-based nanoparticles could be attributed to the catalytic-like mechanism/surface-catalyzed reaction (e.g., in IONs (iron oxide nanoparticles) this is the surface-catalyzed Haber-Weiss cycle and Fenton reaction). (Lower-right) Patterns of cell death in radiosensitization, such as apoptosis, necrosis, mitotic catastrophe, autophagic death, and senescence. Consequently, the enhanced cell-killing effects might result from the complicated physical, chemical and biological effects induced by the complex action of metal-based nanoparticles and ionizing radiation exposure.

In this review, we discuss the advancements in NanoEnhancers to augment the efficacy of radiation therapy in both in vitro and in vivo systems for a range of ionizing radiation types including γ-rays, X-rays, and charged particles based on the type of metallic element. Furthermore, we introduce the potential of translating these preclinical studies of several probable metal-based NanoEnhancers (mainly AGuIX and NBTXR3) into clinical practice. Some general examples of theranostic multimetallic nanocomposites are presented. We also address the underlying biological mechanisms for the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of metal-based nanoparticles. We only briefly discuss the use of gold-based nanoparticles as many review articles are available on this subject, and we mainly focus on other metal-based nanoparticles used for radiotherapy. The metal-based nanoparticles containing unstable radionuclides are excluded from this review.

Metal-based NanoEnhancers for ionizing radiation

Gold-based nanoparticles

Numerous publications have shown the utility of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) for diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer therapy 15, especially in radiotherapy, because gold has a high atomic number, good biocompatibility, and relatively strong photoelectric absorption coefficient 12. In 2000, Herold et al. reported that gold microspheres could produce biologically effective dose enhancement for kilovoltage X-rays 16. And, in 2004, Hainfeld et al. described an improvement in X-ray therapy in tumor-bearing mice following delivery of AuNPs to tumors 17. Thereafter, other studies, using in vitro assays as well as xenografts, focused on the synergistic or sensitizing effect of AuNPs in radiation therapy using X-rays, γ-rays, electron beams and high-energy charged protons/carbon ions 18, 19.

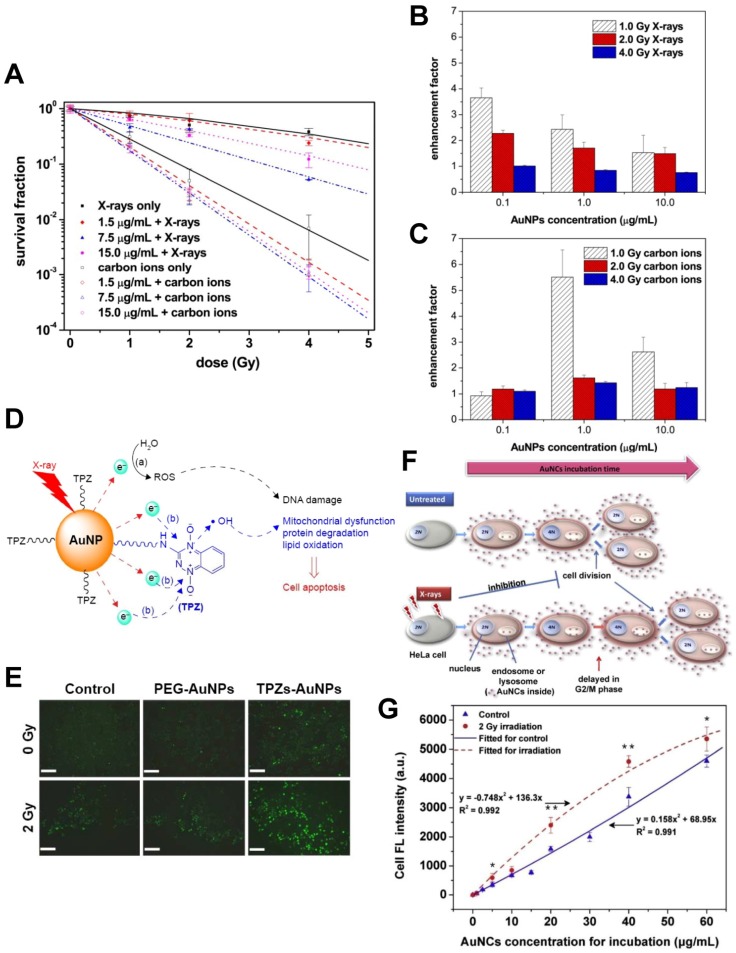

The size, shape, functionalization, concentration, and intracellular distribution of AuNPs can influence their effect on radiation 20-23. Recently, our group published a series of papers in which we presented our studies using gold-based nanoparticles for synergistic chemo-radiotherapy (Fig. 3). We found that AuNPs could significantly improve the hydroxyl radical production and the cell-killing effects of X-rays and fast carbon ions 12. We also synthesized the reductive thioctyl tirapazamine (TPZs)-modified AuNPs (TPZs-AuNPs) and showed their ability for radiation enhancement 24. We further proposed that ionizing radiation exposure was cell cycle phase-dependent for cellular uptake of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs). Additionally, our results demonstrated that the radiation-induced delay of cell division could enhance the retention of AuNCs in the parent tumor cells 25. Koonce et al. also reported that when combined with X-rays, the novel nanomedicine CYT-6091 pegylated AuNPs incorporating tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) (CytImmune, http://www.cytimmune.com/) could inhibit in vivo tumor growth 26. Because CYT-6091 has passed phase 1 trials (NCT00356980 and NCT00436410), the work shows great promise for clinical translation.

Figure 3.

(A-C) Radiation enhancement effect of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) 12. (A) AuNPs improve the cell-killing effects of X-rays and fast carbon ions. (B) AuNPs improve the hydroxyl radical production of X-rays (assessed by 3-CCA). (C) AuNPs improve the hydroxyl radical production of carbon ions (assessed by 3-CCA). (D-E) Synergistic radiosensitizing effect of the reductive thioctyl tirapazamine (TPZs)-modified AuNPs (TPZs-AuNPs) 24. (D) The radiation enhancement mechanism of TPZs-AuNPs proposed in this study. (E) The fluorescence images of ROS with DCFH-DA in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells after X-ray irradiation in the presence of TPZs-AuNPs. Scale bar = 200 μm. (F-G) Dynamically-enhanced retention of gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) in human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells following X-ray exposure 25. (F) Schematic illustration of our strategy for improving cellular uptake of nanoparticles. (G) The fluorescence intensities of cell samples after 24 h incubation with the as-prepared luminescent AuNCs used as both “nano-agents” and fluorescent trafficking probes (control and following 2.0 Gy X-ray irradiation). Reproduced with permission from references: 12, copyright 2015 Elsevier; 24, copyright 2016 Dove Medical Press; 25, copyright 2016 Elsevier.

The biological mechanisms for radiosensitizing and synergistic effects by AuNPs will be further discussed below in section Biological contributions of metal-based NanoEnhancers in RT.

Platinum-based nanoparticles

Platinum-based agents consisting of platinum complexes (cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin, etc.), have been widely used as anticancer drugs in chemotherapy and chemo-radiotherapy 27. However, these compounds are nonselective for tumor cells. Hence, platinum-based nanoparticles (PtNPs) were used for cancer treatment exploiting the EPR effect. Functionalization of these particles could help to lower the volume of distribution and to reduce side effects, thus improving therapeutic efficacy 28.

Relatively few studies have investigated the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of PtNPs for ionizing radiations. Le Sech et al. found that tuning the synchrotron X-ray energy to the LIII edge of the platinum atom bound to DNA could increase the number of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA under dry conditions 29. Also, Kobayashi et al. reported that chloroterpyridine platinum (PtTC) bound to plasmid DNA could enhance the X-ray-induced breaks in DNA in aqueous solution 30. Their results suggested that the enhancement in breaks was mainly mediated by hydroxyl radical (·OH), which originated from the inner-shell excitation of platinum atoms. Corde et al. showed that irradiation above or below the platinum K-shell edge did not enhance the cell death after treating cancer cells with cis-platinum. However, photoactivation of cis-platinum (PAT-Plat) was able to enhance the slowly repairable DSBs while inhibiting the DNA-protein kinase activity, dramatically relocalizing RAD51, hyperphosphorylating BRCA1 (breast cancer 1), and activating the proto-oncogenic cellular Abelson (c-Abl) tyrosine kinase 31, 32. In another study, Porcel et al. presented the prominent radiosensitization of platinum nanoparticles compared to dispersed platinum atoms with fast carbon ions (C6+) where these nanoparticles (NPs) strongly enhanced the breaks in DNA, especially DSBs 33. Furthermore, their results demonstrated that the production of water radicals in the radiosensitization process further damaged DNA as an indirect effect, while the direct effect played a minor role. Also, Porcel et al. reported that platinum nanoparticles could enhance the breaks in DNA with low energy X-rays, γ-rays, and fast helium ions (He2+)34, 35. That platinum nanoparticles were capable of augmenting the radiation effects of fast protons (150 MeV H+) for plasmid DNA was shown by Schlathölter et al. 36. In other studies, Li et al. found that the enhanced carcinostatic effect on human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)-derived cell line, KYSE-70, resulted from apoptosis when the cancer cells were treated with platinum nanocolloid (Pt-nc) in combination with γ-rays, and Pt-nc had an enhancing effect on human normal esophageal epithelial cells (HEEpiC) with irradiation 37, 38.

However, the investigation by Jawaid et al. showed that platinum nanoparticles could greatly decrease the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by X-rays, subsequent Fas expression, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and apoptosis in human lymphoma U937 cells 39. They also found that platinum nanoparticles attenuated the apoptotic pathway, which was mediated by helium-based cold atmospheric plasma-induced ROS 40.

Drug delivery systems (DDS) including liposomes and other lipid-based carriers, macromolecules such as polymer-based nanoparticles, biodegradable materials, and protein-based systems could be used to improve therapeutic benefit by reducing systemic side effects and/or enhancing pharmacological properties 41-44. In this context, Charest et al. reported that LipoplatinTM, a liposomal formulation of cisplatin, improved the cellular uptake of cisplatin and showed a radiosensitizing effect on F98 glioma cells with γ-rays 45. Recently, compared to cisplatin, cisplatin-polysilsesquinoxane (PSQ) nanoparticle (Cisplatin-PSQ NP) comprised of PSQ polymer crosslinked by a cisplatin prodrug was described by Della Rocca et al. that could improve therapeutic efficacy in chemoradiotherapy in a murine model of non-small cell lung cancer 46.

Silver-based nanoparticles

According to previous investigations 47, 48, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exhibit important antimicrobial activity 49 and could also be used as potential anticancer therapeutic agents 50, 51 because of their intrinsic therapeutic properties. In cancer therapy, anti-proliferative effects of AgNPs might result from different underlying mechanisms, including induction of apoptosis 52-54, production of ROS 55, inhibitory action on the efflux activity of drug-resistant cells 56, and reactivity with glutathione (GSH) molecules 57.

Many studies demonstrated that AgNPs could serve as radiosensitizers and enhancers for radiotherapy. Gu's group observed that AgNPs (20 nm and 50 nm) sensitized glioma cells in vitro and concluded that the release of Ag+ cations from the silver nanostructures inside cells might result in the radiosensitizing effect 58. Furthermore, following delivery of AgNPs to tumors, they could improve X-ray therapy for rats bearing C6 glioma 59 and mice bearing U251 glioma 60. Similarly, Huang et al. showed that biocompatible Ag microspheres improved the cell-killing effects of X-rays on gastric cancer MGC803 cells 61. Lu and coworkers synthesized AgNPs using egg white and observed marked X-ray irradiation enhancement on human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells 62. Significant cytotoxic and radiosensitizing effects of AgNPs on triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells in vitro and in vivo were demonstrated by Swanner et al. 63. AgNPs also induced elevated DNA damage, increased expression of Bax/caspase-3 leading to apoptosis, decreased expression of Bcl-2, and reduction of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and total GSH contributing to the enhancement in radiosensitivity of human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells 64. The results indicated no accumulation of cells in the sensitive G2/M phase. Elshawy et al. observed enhancement by AgNPs of the cell-killing effects of γ-rays on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells, which might result from the inhibition of proliferation, increased activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and caspase-3, and altered expression of caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2 genes 65.

The above results illustrate that though silver is cheaper than gold, AgNPs are less inert and biocompatible than AuNPs and the biological mechanisms for radiosensitization and synergistic effects by AgNPs could be more complicated.

Gadolinium-based nanoparticles

Gadolinium (Gd, rare earth (lanthanide) metal) chelates have been commonly used as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents for T1 contrast 66. Hence, for a more precise and accurate irradiation, Gd chelates have been applied in MRI-guided radiotherapy. In 1996, Young et al. found that Gd (III) texaphyrin (Gd-tex2+), a porphyrin-like complex, could serve as an efficient radiosensitizer 67. In tumor-bearing mice, MRI scanning confirmed the selective localization of Gd-tex2+ in tumors. Motexafin gadolinium (MGd), a metallotexaphyrin, can catalyze the oxidation of intracellular reducing metabolites and generate ROS. Several large studies demonstrated that MGd was capable of potentially enhancing the cytotoxic effects of radiation through several mechanisms as well as selectively inhibiting tumor cell growth by itself 68. Consequently, Gd-based agents show great promise for multifunctional theranostic (diagnostic and therapeutic) applications in clinical practice. In addition to its application as a positive MRI T1 contrast agent 69, gadolinium-based nanoparticles (GdNPs) have been identified as valuable theranostic sensitizers for radiation therapy 70, 71(Table 1). More importantly, GdNPs, such as AGuIX (Activation and Guidance of Irradiation by X-ray) 87, exhibit diminished or no toxicity in preclinical studies employing mice and monkeys and are eliminated rapidly via the kidneys 88, 89. In contrast, the release of free Gd (III) from acyclic chelates constituting commonly used conventional Gd-based MRI contrast agents in the acidic conditions of the kidneys can be responsible for the high frequency of serious and sometimes fatal nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) observed in patients with renal failure.

Table 1.

Application of theranostic GdNPs to radiotherapy

| NP/core type | Coating | Size | Functionalization | Radiation/energy | Cells & tumor models | Function | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd-DTPA-loaded-microparticles | Chitosan | 4.1 μm 3.3 μm |

None | Thermal neutron | None | Gd-NCT (in vitro γ-ray emission) | 72 |

| Gd-DTPA-loaded-nanoparticles | Chitosan | 430 nm 452 nm 391 nm 214 nm |

None | Thermal neutron | C57BL/6 mice with B16F10 (malignant melanoma) | Gd-NCT | 73-75 |

| Gd-DTPA-loaded-nanoparticles | Chitosan | 430 nm | None | None | (MFH) Nara-H cells (human sarcoma) | MRI | 76 |

| Gd-DTPA-loaded-nanoparticles | Calcium phosphate-polymeric micelle | 55 nm | None | Thermal neutron | C26 cells (colon adenocarcinoma) BALB/c mice with C26 |

MRI Gd-NCT |

77, 78 |

| Gd2O3 | Polysiloxane shell | sub-45 nm | None | 50 keV monochromatic synchrotron X-ray 45 MeV proton |

CT26 cells (colon adenocarcinoma) | Improve ROS yields | 79 |

| Gd2O3 | Polysiloxane shell | ~7.3 nm | Pentafluorophenyl ester-modified PEG | Thermal neutron | EL4 and EL4-Luc cells (lymphoma) | Fluorescence imaging MRI Gd-NCT |

80 |

| Gd2O3 | Polysiloxane shell | sub-5 nm | DTPA | 660 keV γ-ray (source of 137Cs) 6 MV X-ray X-ray microbeam (~72 Gy s-1 mA-1) |

U87 cells (human glioblastoma) SQ20B cells (human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma) LTH cells (Human T Lymphocytes) Fischer 344 rats with 9L cells (glioma) |

MRI Radiosensitization |

81-83 |

| Gd2O3 | Polysiloxane shell | 3 nm | DOTA | X-ray microbeam (~72 Gy s-1 mA-1) | Fischer 344 rats with 9L | MRI Radiosensitization |

84 |

| Gadoteridol (C17H29GdN4O7) | Coatsome EL-01-N liposome | N/A | None | Thermal neutron | BALB/c mice with C26 | MRI Gd-NCT |

85 |

| Gd2O3 | Withania somnifera extract | 25-35 nm | None | 660 keV γ-ray (source of 137Cs) | Swiss albino mice with EAC cells (Ehrlich ascites carcinoma) | Radiosensitization | 86 |

DOTA: 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N'',N'''-tetraacetic acid; DTPA: diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; Gd-NCT: gadolinium neutron-capture therapy; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PEG: polyethylene glycol; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

Among the lanthanide elements, Gd is of great theoretical and practical interest to researchers focusing on neutron capture therapy (NCT) because of the high neutron capture cross-section of nonradioactive 157Gd 90. Tokumitsu et al. have shown that as-prepared biodegradable gadopentetic acid (Gd-DTPA)-loaded chitosan microparticles could emit γ-rays in the thermal neutron irradiation test, suggesting that the particles could be used in gadolinium neutron-capture therapy (Gd-NCT)72. Subsequent in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that Gd-loaded chitosan nanoparticles were possible agents for Gd-NCT 73-76. Studies evaluating other types of GdNPs, including calcium phosphate-polymeric micelles, Gd2O3 cores/polysiloxane shell, and gadoteridol/liposome, reported similar results 77, 78, 80, 85.

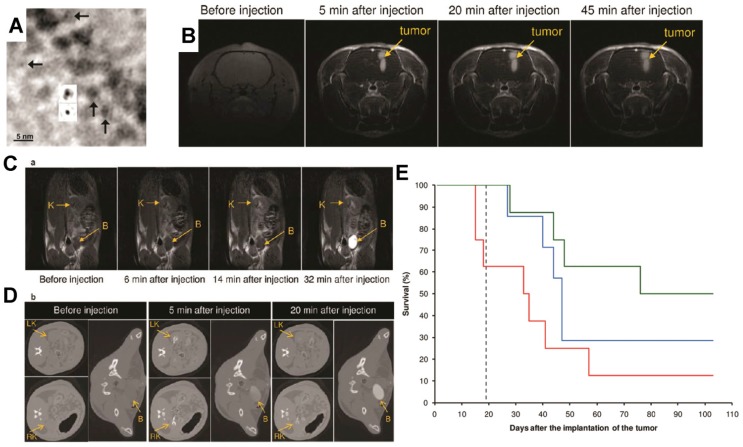

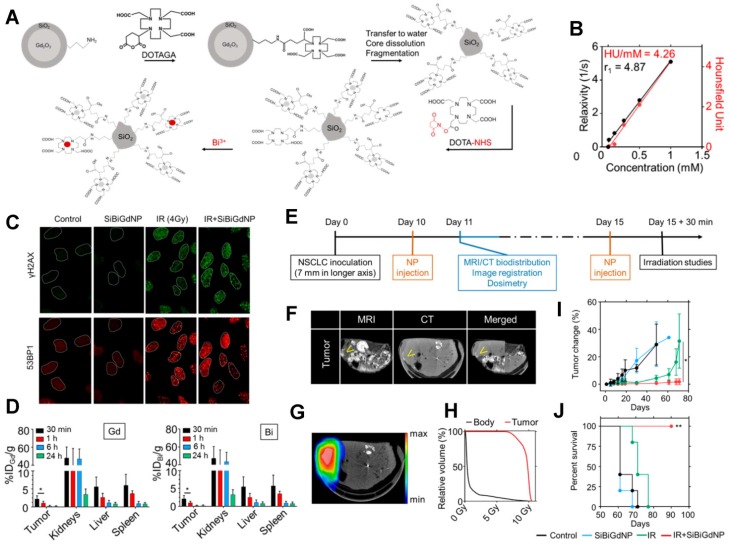

The radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of GdNPs when combined with other ionizing radiation types, such as γ-rays, X-rays, and charged particles (protons and heavy ions), have been well established. Mowat et al. found that Gd2O3-based nanoparticles could be used as sensitizing agents to improve the killing effects of both γ-rays and X-rays 81. Furthermore, Le Duc et al. showed that the GdNP improved the survival of rats bearing aggressive brain tumors by means of microbeam radiation therapy (MRT) while applied to MRI 82(Fig. 4). Therefore, this sub-5 nm GdNP consisting of a polysiloxane network surrounded by Gd chelates (cyclic, not acyclic) was named “AGuIX” 91(Table 2). As described by Mignot et al., these small rigid platforms (SRP) were synthesized by an original top-down process, which consists of gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3) core formation, encapsulation by a polysiloxane shell grafted with DOTAGA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1-glutaric anhydride-4,7,10-triacetic acid) ligands, Gd2O3 core dissolution following chelation of Gd3+ by DOTAGA ligands, and polysiloxane fragmentation 84. AGuIX nanoparticles exhibit potential as a theranostic drug for radiation therapy, including MRI contrast, radiosensitization, and adapted biodistribution due to the EPR effect 93, 94, 96, 99-101. A phase 1 trial (NCT02820454) is in progress in France by the AGuIX group (NH TherAguix, http://nhtheraguix.com/). It was reported that the first in human injection of AGuIX was carried out at Grenoble hospital in July 2016.

Figure 4.

Ultrasmall gadolinium-based nanoparticles (GdNPs) induce both a positive contrast for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a radiosensitizing effect. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) phase-contrast imaging at low spatial resolution of Gd2O3 cores after encapsulation in a polysiloxane shell (insets show projected potential calculations of Gd2O3 after and before polysiloxane formation (top and bottom, respectively)). (B) MRI T1-weighted images of the brain of a 9L glioma-bearing rat before and after intravenous injection of GdNPs. (C) T1-weighted images of a slice including a kidney (K) and the bladder (B) of a rat before and after intravenous injection of GdNPs. (D) Synchrotron radiation computed tomography (SRCT) images of a series of successive transverse slices including the right and left kidneys (RK and LK, respectively) and the bladder (B) of a 9L glioma-bearing rat. The images were recorded before and after the intravenous injection of GdNPs. (E) Survival curve comparison obtained on 9L glioma-bearing rats without treatment (black dashed curve), only treated by microbeam radiation therapy (MRT)(blue curve), and treated by MRT 5 min (red curve) and 20 min (green curve) after GdNP intravenous injection during 103 days after tumor implantation. Reproduced with permission from reference 82, copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

Table 2.

Application of AGuIXa to radiotherapy

| Radiation/energy | Cells & tumor models | Function | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 220 kVp & 6 MV X-ray | HeLa cells (human cervical carcinoma) | Radiosensitization | 91 |

| 250 kV & 320 kV X-ray | SQ20B, FaDu and Cal33 cells (human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma) Athymic nude mice with SQ20B |

Radiosensitization | 92 |

| X-ray microbeam (62 Gy s-1 mA-1) | Fischer 344 rats with 9L | MRI Radiosensitization |

93 |

| 200 keV X-ray | NMRI nude mice with H358-Luc cells (human non-small cell lung cancer) | MRI Radiosensitization |

94 |

| 220 kVp & 6 MV X-ray | Panc1 cells (human pancreatic cancer) | MRI Radiosensitization |

95 |

| 220 kV & 320 kV X-ray | B16F10 cells C57BL/6J mice with B16F10 |

MRI Radiosensitization |

96 |

| 90 keV X-ray | F98 cells (glioma) | Radiosensitization | 97 |

| X-ray microbeam (~72 Gy s-1 mA-1) | Fischer 344 rats with 9L | MRI Radiosensitization |

98 |

| 220 kVp & 6 MV X-ray | Capan-1 cells (human pancreatic adenocarcinoma) CrTac: NCr-Fox1nu mice with Capan-1 Cynomolgus monkeys (macaca fascicularis) |

MRI Radiosensitization |

99 |

| 6 MV X-ray | Fischer 344 rats with 9L-ESRF cells (glioma) | MRI Radiosensitization |

100 |

| 6 MV X-ray | Capan-1 cells CrTac: NCr-Fox1nu mice with Capan-1 |

MRI Radiosensitization |

101 |

| 1.25 MeV γ-ray (source of 60Co) | U87 cells | Radiosensitization | 102 |

| 1.25 MeV γ-ray (source of 60Co) 25-80 keV monochromatic synchrotron X-ray |

F98 cells | Radiosensitization | 103 |

| 150 MeV proton | None | Improve SSB & DSB yields | 104 |

| 150 MeV/uma He2+ (LET = 2.33 keV/μm) 270 MeV/uma C6+ (LET = 13 keV/μm) |

CHO cells (Chinese hamster ovary) | Radiosensitization | 105 |

aAGuIX: Activation and Guidance of Irradiation by X-ray, the sub-5 nm GdNPs based on a polysiloxane network surrounded by Gd chelates.

DSB: double-strand break; SSB: single-strand break.

Iron-based nanoparticles

In addition to GdNPs, iron-based nanoparticles have been investigated as theranostic magnetic nanoparticles 106, 107, including inorganic paramagnetic iron oxide (or magnetite) nanoparticles, or superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) 108. However, instead of T1 contrast like GdNPs, iron oxide nanoparticles (IONs) have been used as negative T2 MRI contrast agents 109. Furthermore, IONs are considered ideal agents for diagnosis, treatment, and treatment monitoring of cancers because of their excellent properties, such as facile synthesis, biocompatibility, and biodegradability 110. In particular, IONs have potential applications not only as MRI contrast agents but also in photothermal therapy (PTT), photodynamic therapy (PDT), magnetic hyperthermia, and chemo/biotherapeutics 111-113.

Another promising application of IONs is as radiosensitizers/enhancers. Although the atomic number of iron (Fe, Z = 26) is relatively low, IONs are mostly used in combination with low-linear energy transfer (LET) kV and MV X-rays. In an orthotopic rat model of prostate cancer following intratumoral injection of an aminosilane-type shell-coated SPION with a core diameter of 15 nm, a combination of thermotherapy and X-ray irradiation was shown to more effectively reduce tumor growth than radiation alone 114. This result might be attributed in part to the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects by magnetic nanoparticles. Other studies also reported notable in vitro radiosensitization of prostate cancer cells by X-rays in conjunction with IONs 115, 116. Also, it has been demonstrated that IONs could sensitize other tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. For instance, Huang et al. showed that cross-linked dextran-coated IONs (CLIONs) were internalized by HeLa cells and EMT-6 mouse breast cancer cells and improved the killing effects of X-ray irradiation 117. Recently, several groups have presented similar results 118 showing the application of IONs together with MRI 119. Other studies indicated that X-ray radiosensitization by IONs might be attributed to the production of ROS owing to IONs' surface-catalyzed Haber-Weiss cycle and Fenton reaction 120-122. Furthermore, in other studies, the IONs-mediated radiosensitization was observed in combination with monoenergetic synchrotron X-ray radiation 123, 124. Kleinauskas et al. reported that IONs enhanced the efficacy of monochromatic Fe K-edge synchrotron X-rays more significantly than conventional broadband X-rays 115. Considering the limitations of conventional proton therapy (PT), Kim et al. evaluated the effect of IONs for PT and demonstrated the radiosensitizing effects of IONs in vitro and in vivo 125. The follow-up studies also provided evidence for this promising application of IONs 126-128. It was also reported that IONs were able to enhance radiation cytotoxicity of γ-rays 129. In addition to IONs, other types of iron based-nanoparticles have shown radiosensitizing effects 130.

Although a number of ION formulations have been approved by the FDA, many studies have shown the toxic effects of IONs 110. To overcome this disadvantage, surface modification and functionalization with various molecules and ligands would be helpful in addressing clearance from the circulation and retention in the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) as well as improving tissue targeting, biocompatibility, and stability 131. Currently, IONs remain as the ideal platform for cancer theranostics.

Hafnium-based nanoparticles

Hafnium oxide (hafnia, HfO2) has been shown to possess photo-luminescent properties 132 and HfO2 nanoparticles (HfO2 NPs) exhibit chemical inertness in cellular and subcellular systems 133-135. Hence, owing to the high atomic number, electron density, and chemical stability of hafnium/hafnia, HfO2 NPs show promising potential as sensitizers for radiation therapy as well as X-ray contrast agents 136.

NBTXR3, the functionalized HfO2 NPs developed by Nanobiotix (http://www.nanobiotix.com/_en/), are 50-nm-sized crystalline nanoparticles bearing a negative surface charge. NBTXR3 were designed for direct local intratumoral injection and subsequent radiosensitization 6, 137. Subsequently, it has been demonstrated by Monte Carlo simulation that NBTXR3 crystalline nanoparticles exposed to high-energy photons could promote a significant radiation dose enhancement, and the obvious radiosensitizing effects of NBTXR3 in vitro and in vivo were presented 138-140. Also, nonclinical toxicology evaluation of this agent showed a good tolerance. Many clinical trials (7 records) were carried out using NBTXR3 crystalline nanoparticles-RT combination (Table 3). The phase 1 trial of NBTXR3 (NCT01433068) started in 2011 and completed in 2015. It was shown that human injection (22 sarcoma patients in France) was well tolerated until 10% of tumor volume with preoperative external beam radiotherapy and did not result in leakage of these nanoparticles into the adjoining healthy tissues, while NBTXR3 NPs were used as a medical device to reduce the tumor size before surgery (performed 6-8 weeks after RT completion) 141-144. Currently, several multinational phase 1/2 trials and one phase 2/3 trial are ongoing and recruiting participants for the treatment of head and neck cancer (squamous cell carcinoma), rectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer), prostate cancer, and adult soft tissue sarcoma.

Table 3.

Clinical trials investigating NBTXR3a crystalline nanoparticle-RT combination (records in https://clinicaltrials.gov/)

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Start year | Phase | Indication | Number of patients | Country & region | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01433068 | 2011 | I | Adult soft tissue sarcoma | 22 | France | Completed |

| NCT01946867 | 2013 | I | Head and neck cancer | 48 | France, Spain | Recruiting |

| NCT02379845 | 2015 | II/III | Adult soft tissue sarcoma | 180 | Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Philippines, Poland, Romania, South Africa, Spain | Recruiting |

| NCT02465593 | 2015 | I/II | Rectal cancer | 42 | Taiwan | Recruiting |

| NCT02721056 | 2015 | I/II | Hepatocellular carcinoma; liver cancer | 200 | France | Recruiting |

| NCT02805894 | 2016 | I/II | Prostate cancer | 96 | United States | Recruiting |

| NCT02901483 | 2016 | I/II | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 42 | Taiwan | Recruiting |

aNBTXR3, 50-nm-sized crystalline HfO2 nanoparticles bearing a negative surface charge.

Chen et al. synthesized hafnium-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (Hf:HAp NPs) by wet chemical precipitation and showed marked γ-ray irradiation enhancement of Hf:HAp NPs, probably resulting from intracellular ROS formation, for human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells using in vitro assay as well as xenografted tumors 145. A rational design of nanoscale metal organic frameworks (NMOFs) composed of hafnium (Hf4+) and tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) was also described with significant radiosensitizing effects of pegylated Hf-TCPP NMOFs exhibiting efficient clearance from the body when combined with X-rays 146.

Other types of metallic element-based nanoparticles

A considerable number of nanoparticles based on other metallic elements have demonstrated efficiency in radiosensitization or synergistic cell-killing effects for radiation therapy with single functionality or multifunctionality. These elements include bismuth, titanium, tantalum, cerium, germanium, zinc, and tungsten and were evaluated in several studies.

Due to the strong absorption of X-rays, bismuth nanoparticles (BiNPs) were employed as contrast agents for X-ray imaging 147. Also, BiNPs led to higher dose enhancement than AuNPs and PtNPs for diagnostic X-rays, attributed to both photoelectrons and Auger electrons with respect to the cell and the nucleus 10. The synthesized NPs mainly comprise Bi2Se3, Bi2S3, and Bi2O3 NPs stabilized by different ligands and molecules. Hossain and coworkers used BiNPs conjugated with folic acid to selectively detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs) combined with collimated X-rays, and showed the improved killing of localized CTCs with the dose of primary X-rays 148. Other investigators also reported that biocompatible Bi2Se3 NPs exhibited diminished toxicity and the potential to function as theranostic agents for radiation therapy, including multimodal imaging, radiosensitization, and PTT 149, 150. Moreover, several studies have revealed that Bi2S3 and Bi2O3 NPs could serve as radiosensitizers and enhancers for radiotherapy 151-156. Alqathami et al. validated and quantified the radiation dose enhancement of Bi2S3 and Bi2O3 NPs using phantom cuvettes and novel 3D phantoms and found that the radiation enhancement was greater when irradiating with kV X-rays compared to MV X-rays 157. Nevertheless, a recent study showed that Bi2Se3 NP, also the catalytic topological insulator, could be used as a potential radioprotective agent due to its ability to scavenge free radicals 158.

Titanium-based nanoparticles can also function as NanoEnhancers. Titanium dioxides (titania, TiO2), sometimes used as a disinfectant, is employed to eradicate cancer cells using photocatalytic chemistry 159. It has been reported that two human glioblastoma cells, SNB-19 and U87MG, were radiosensitized following incubation with titanate nanotubes (TiONts)160. Also, titania nanoparticles modified with polyacrylic acid (PAA) and H2O2 (PAA-TiO2/H2O2 NPs) enhanced the cell-killing effects of X-rays mediated through the generation of ROS/hydroxyl radicals, which was assessed by colony forming assays and xenografts 161. Interestingly, this PAA-TiO2/H2O2 NP was also capable of releasing H2O2 molecules from the NP surface 162. It was suggested that Čerenkov radiation (CR) contributes to the radiation enhancement in the presence of TiO2 NPs 163.

Tantalum-based NPs can play a role in radiosensitizing or synergistic cell-killing effects for radiation therapy. Using plasmid DNA, Cai et al. demonstrated that secondary electrons emitted from the soft X-ray-exposed tantalum surface induced DNA damage more efficiently than X-ray alone 164. Subsequently, it was shown that tantalum pentoxide nanoceramics/ceramic nanostructured particles (Ta2O5 NSPs) exposed to MV X-ray photons could promote an obvious radiation dose enhancement in 9L glioma cells 165. Several relevant follow-up studies concerning Ta2O5 NSP radiosensitization have been published 166-169. Considering the lower oxygen partial pressure (pO2) inside tumors and advantages of multifunctional nanotheranostics, a series of modified and functionalized tantalum oxide nanoparticles (TaOx NPs) have been synthesized, and their diagnostic and therapeutic application in radiotherapy has been demonstrated 170-173.

Numerous studies have investigated cerium (another high-Z lanthanide rare earth element) oxide (ceria, CeO2) nanoparticles and demonstrated their diverse applications, such as radioprotection, radiosensitization, anticancer therapeutics, and antioxidation 174-178. Tarnuzzer et al. found that ceria NPs protected the normal human breast CRL-8798 epithelial cells but not the human breast cancer MCF-7 cells from radiation-induced cell death 179. Subsequently, other groups presented detailed investigations of the effects of CeO2 NPs 180-184. It was also confirmed that CeO2 NPs could enhance the cytotoxic effects of radiation therapy. Cerium oxide nanoparticles could sensitize pancreatic cancer cells to kV X-rays by improving ROS production, as shown by in vitro assays as well as xenografts 185. Other groups also reported similar results when evaluating X-rays, electrons, and protons 186-188. Thus, like PtNPs and Bi2Se3 NPs, CeO2 NPs have dual effects on radiotherapy. These results suggest that metal-based nanoparticles act not only as radiosensitizers but also as radioprotectors in radiation therapy 189. It is, therefore, important to investigate the underlying mechanisms of metal-based nanoparticles-induced dual effects.

In addition to the metallic elements listed above, other nanoparticles also show promise as effective NanoEnhancers for future radiotherapy. For example, inorganic germanium nanoparticles (GeNPs) could enhance the radiosensitivity of cells 190. Similarly, the potential of zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles 191, 192 for radiosensitization is obvious from both in vitro and in vivo studies, and tungsten-based nanoparticles have also been reported as probable radiosensitizers 193-196 (Fig. 5).

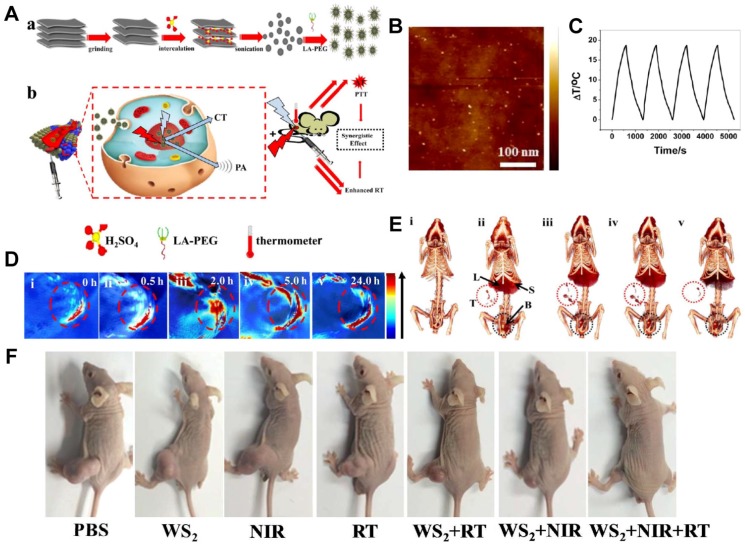

Figure 5.

Tungsten sulfide (WS2) quantum dots (QDs) as multifunctional nanotheranostic agents for in vivo dual-modal image-guided photothermal/radiotherapy synergistic therapy. (A) Schematic illustration of WS2 QDs for dual-mode computed tomography (CT)/photoacoustic (PA) imaging and photothermal therapy (PTT)/radiation therapy (RT) synergistic therapy. (B) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) topography images of the as-prepared WS2 QDs. (C) Temperature change of WS2 QD solution at a concentration of 100 ppm over four laser on/off cycles. (D) PA images of BEL-7402 human hepatocellular carcinoma-bearing mice before and after the intravenous injection of WS2 QDs. (E) CT images of tumor before and after the intravenous injection of WS2 QDs. (F) Representative images of different groups of BEL-7402 human hepatocellular carcinoma-bearing mice after different administrations at the end of PTT and RT. Reproduced with permission from reference 194, copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

Theranostic multimetallic nanocomposites for future RT

As discussed, given the advantages of multifunctional theranostics in radiation oncology, a large number of hybrid nanomaterials based on multimetallic elements (e.g., bimetallic and trimetallic) have been prepared and might help to improve therapeutic benefits for future radiation therapy. In this section, we present some general examples of these theranostic nanoparticles (Table 4), and discuss the advancements in NanoEnhancers.

Table 4.

Multifunctional hybrid metal-based nanomaterials for radiation therapy

| NP type | Metal 1 | Metal 2 | Metal 3 | Coating | Size (nm) | Functionalization & delivered drug | Radiation/energy | Cells & tumor models | Function | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spheres | Au | Pt (cisplatin) | None | None | 50 | MUA | 660 keV γ-ray (source of 137Cs) | S1, S2, and SP56 cells (human glioblastoma multiforme) | Chemotherapy Radiosensitization |

197 |

| Dendrites | Au | Pt | None | PEG | 30 | None | X-ray | 4T1 cells (breast cancer) | CT imaging Radiosensitization PTT |

198 |

| Spheres | Au | Gd (chelates) | None | None | N/A | DTDTPA | 660 keV γ-ray (source of 137Cs) X-ray microbeam (~72 Gy s-1 mA-1) |

U87 cells Sprague-Dawley rats with osteosarcoma Fischer 344 rats with 9LGS cells (glioma) |

MRI Radiosensitization Monitoring and evaluation |

199 |

| Polymeric micelles | Au | Fe (SPIONs) | None | PEG-PCL | 100 | None | 150 kVp X-ray | HT1080 cells (human fibrosarcoma) Nu/nu mice with HT1080 |

MRI Radiosensitization Monitoring and evaluation |

200 |

| Spheres | Au (core) | Mn (MnO2, shell) | None | PEG | ~100 | None | 160 keV X-ray | 4T1 cells BALB/c mice with 4T1 |

MRI Radiosensitization |

201 |

| Spheres | Au (core) | Mn (MnS, shell) | Zn (ZnS, shell) | PEG | ~110 | None | X-ray | 4T1 cells BALB/c mice with 4T1 |

MRI Radiosensitization |

202 |

| Spheres | Pt | Fe | None | Cysteamine | 3 | None | 6 MV X-ray | HEK293T cells (human embryonic kidney) HeLa cells |

Chemotherapy Radiosensitization |

203 |

| Spheres | Ag | Fe (SPIONs) | None | None | ~102 | Epidermal growth factor receptor-specific antibody | X-ray | CNE cells (human nasopharyngeal carcinoma) | MRI Radiosensitization |

204 |

| Flakes | Gd (Gd (III), doped) | W (WS2, base) | None | C18PMH-PEG | ~0.268 | None | X-ray | 4T1 cells BALB/c mice with 4T1 |

CT imaging MRI PA imaging Radiosensitization PTT |

205 |

| Clusters | Gd | W | None | BSA | 3.5 | None | X-ray | BALB/c mice with MDA-MB-231 (human breast adenocarcinoma) BALB/c mice with BEL-7402 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) |

CT imaging MRI Radiosensitization PTT |

206 |

| Particles/fragments | Gd (AGuIX, silica-based) | Bi (Bi (III), entrapped) | None | None | sub-5 | DOTAGA DOTA-NHS |

220 kVp & 6 MV X-ray | A549 cells (human non-small cell lung cancer) Mice with A549 |

CT imaging MRI Radiosensitization |

207 |

| Spheres | Gd/ Eu (doped) |

Zn (ZnO, base) | None | None | 9 | None | 200 kVp X-ray 1.25 MeV γ-ray (source of 60Co) |

PC3 cells (human prostate carcinoma) L929 cells (fibroblast) HeLa cells |

CT imaging MRI Radiosensitization PDT |

208 |

| Spheres | Fe (SPIONs, core) | Zn (ZnO, shell) | None | None | < 200 | Transferrin receptor antibody Doxorubicin |

6 MeV X-ray | SMMC-7721 cells (human hepatocellular carcinoma) BALB/c mice with SMMC-7721 |

MRI Chemotherapy Radiosensitization |

209 |

| “Bullet-like” | Bi (Bi2Se3, shell) | Mn (MnSe, core) | None | PEG | Length: 132 Width: 111 |

None | 140 keV X-ray | 4T1 cells BALB/c mice with 4T1 |

CT imaging MRI Radiosensitization PTT |

210 |

| Sheets | Bi (Bi2S3) | Mo (MoS2) | None | PEG | ~300 | None | X-ray | L929 cells BALB/c mice with 4T1 |

CT imaging PA imaging Radiosensitization PTT |

211 |

BSA: bovine serum albumin; C18PMH: poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene); CT: computed tomography; DOTAGA: 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1-glutaric anhydride-4,7,10-triacetic acid; DTDTPA: dithiolated derivative of the diethylenetriaminepentacetic acid; MUA: mercaptoundecanoic acid; NHS: N-hydroxysuccinimide; PA: photoacoustic; PCL: polycaprolactone; PDT: photodynamic therapy; PTT: photothermal therapy.

Broadly, several factors determine the functions and applications of the multimetallic nanocomposites (Fig. 6) including types of elements, their sizes, structures, shapes, coatings, functionalizations, and drugs to be delivered. As reviewed in previous sections, most high Z metallic elements were applied for radiosensitization including X-ray contrast and computed tomography (CT)198. Magnetic metals, such as Gd and Fe, were utilized for MRI contrast 202, 205, and concurrent chemotherapy was achieved in the presence of Pt and its complexes 197, 203.

Figure 6.

Ultrasmall silica-based bismuth gadolinium nanoparticles (gadolinium-based AGuIX (Activation and Guidance of Irradiation by X-ray) nanoparticles with entrapped Bi (III)) for dual magnetic resonance/CT image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT). (A) These agents were synthesized by an original top-down process, which consists of Gd2O3 core formation, encapsulation by polysiloxane shell grafted with DOTAGA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1-glutaric anhydride-4,7,10-triacetic acid) ligands, Gd2O3 core dissolution following chelation of Gd (III) by DOTAGA ligands, and polysiloxane fragmentation. Moreover, at the final stage of the synthesis, DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N'',N'''-tetraacetic acid)-NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) ligands were grafted to the surface to entrap free Bi3+ atoms into the final complex. (B) MRI (relaxivity) and CT (Hounsfield units) linear relation with concentration of nanoparticles (metal) in aqueous solution. (C) Qualitative representation of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1) foci formation, with and without 4 Gy irradiation, with and without nanoparticles, 15 min post-irradiation. (D) Biodistribution study performed by ICP-MS (inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry) in animals after intravenous injection of nanoparticles. (E) Experimental timeline based on a current clinical workflow for MRI-guided radiotherapy. (F) Fusion of the CT and MRI images. Yellow arrows indicate the inceased contrast in the tumor. (G) Dosimetry study performed for a single fraction of 10 Gy irradiation delivered from a clinical linear accelerator (6 MV). (H) Dose-volume histogram showing the radiation dose distribution in the tumor and in the rest of the body. (I) Mean tumor volume of each group. (J) Overall survival of each treatment cohort. Reproduced with permission from reference 207, copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

Multimetallic nanocomposites are well-designed metal-based hybrid materials with diverse structures and shapes consisting of at least two metals. Besides their radiosensitizing and synergistic effects as well as CT and MR imaging capabilities, multimetallic nanocomposites have exhibited a variety of additional functions in drug delivery 209, PTT 210, 212, PDT 208, PA (photoacoustic) imaging 211, 213, and monitoring and evaluation during treatment 199, 200. In particular, the multimetallic nanocomposites termed upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) containing rare earth elements 214 have attracted great interest in radiation oncology 215. Overall, UCNPs can generate cytotoxic ROS 216. Moreover, it was demonstrated that UCNPs could play a role in PTT 217 and diagnostic imaging 218. Besides the above-mentioned NPs, a variety of metallic, non-metallic, and metallio-organic nanocomposites have been formulated and studied as promising multifunctional theranostic NanoEnhancers 219-221.

Biological contributions of metal-based NanoEnhancers in RT

As described above, the metal-based NanoEnhancers show promising efficacy against cancers in both in vitro and in vivo systems for a range of ionizing radiation types including γ-rays, X-rays, and charged particles. However, the predicted enhancement in physical absorbed doses based on the Monte Carlo simulations often differed from the observed biological enhancement, with the former being less than the latter 222. Hence, the amplification of cell-killing effects for ionizing radiation not only results from the increase in physical dose, but also mainly from other fluctuations or responses in biological systems. In addition to the major role of oxygen radicals in metal-based NanoEnhancer radiosensitization 223, 224, numerous investigations have suggested the existence of complicated processes in the biological phase. It appears that other possible mechanisms underlie the sensitizing and synergistic effects of metal-based NanoEnhancers in radiotherapy, which may vary based on the metallic element of the NanoEnhancer. Moreover, the enhancement depends on cellular and subcellular distribution and location of metal-based NanoEnhancers with respect to the cell and the nucleus 10, 225, 226 (Fig. 2, lower-left). Also, metal-based NanoEnhancers in tumor cells or organelles, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 227, can elicit unidentified cellular biochemical changes 228-230 leading to their radiosensitizing and synergistic effects in combination with ionizing radiations. Thus, the enhanced cell-killing effects might result from the complicated physical, chemical, and biological effects induced by the complex action of metal-based nanoparticles and ionizing radiation exposure 8, 231.

Although a comprehensive understanding of the biological mechanisms involved in radiosensitization of metal-based NanoEnhancer is crucial for their correct design and clinical application, relatively limited information is available on this subject. The existing investigations mainly focused on the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of AuNPs and AgNPs 232, 233. The underlying mechanisms for radiosensitization with conventional chemical and biological agents as well as metal-based NanoEnhancers mainly consist of ROS generation, targeting of DNA damage response and repair, inhibition of cell cycle checkpoint machinery, modification of the tumor microenvironment, antiangiogenesis, and immune modulation 234. As displayed in Fig. 2 (upper-right), probable biological mechanisms mainly consist of oxidative stress, cell cycle arrest, DNA repair inhibition, autophagy, and ER stress, which are discussed separately in this section.

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction

Oxidative stress could damage cells through the interactions between critical biological targets or reducing substances and generated ROS in the presence of ionizing radiations and metal-based NanoEnhancers 235. The primary targets and reducing substances mainly comprise cellular membrane structures, DNA, proteins, lipids, and GSH. Also, pO2 inside tumors has a prominent role during the course of RT and the hypoxic tumor microenvironment weakens ROS production and oxygen fixation reaction, decreasing the RT efficacy 225. Mitochondria are believed to be the amplifiers of radiation-induced ROS production 236 and, as the “energy powerhouse of the cell”, are unavoidable early targets in the design of next generation metal-based NanoEnhancers with organelle-targeting capability 237-239. Mitochondrial dysfunction, which includes mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage, mobilization of cytochrome c, and other significant effects of oxidative stress, could trigger the cell death such as apoptosis. Taggart et al. provided the first evidence for the involvement of mitochondria in the AuNPs-mediated radiosensitizing effect 240. The same group recently identified mitochondria as a probable driver for the radiosensitization by AuNPs outside the nucleus when irradiating cytoplasm with a very low-energy ultrasoft X-ray microbeam (278 eV carbon K-shell X-rays) without causing nuclear damage 241. In addition, protein disulphide isomerase (PDI) residing in or on the ER/nucleus/mitochondria/cytosol/cell surface as well as mitochondrial oxidation were identified as novel targets during radiosensitization by AuNPs 242. Nevertheless, the nucleus has been proven to be one of the most sensitive and major targets for metal-based NanoEnhancers.

Interestingly, in contrast to the above results, some previous studies have demonstrated that metal-based NanoEnhancers could diminish DNA repair efficiency as well as result in accumulation of cells in the sensitive G2/M phase. However, when combined with X-rays, no notable enhancement in ROS production 160, 243 was observed, and even reduction in both endogenous and radiation-generated ROS was reported 187.

Cell cycle arrest/redistribution

Ionizing radiation exposure has been demonstrated to delay mammalian cell cycle progression by inducing G1 or G2 phase arrest 244, 245. As part of the complex cellular responses to DNA damage, these cell cycle checkpoint activations involve DNA repair. Therefore, inhibition of the cell cycle checkpoint machinery is considered a promising way to sensitize tumors to ionizing radiations. The cell cycle phase at the time of irradiation is equally important and can influence the radiosensitivity of cancer cells. The cells in late S phase are most radioresistant, while the cells in G2/M phase are most radiosensitive (radiosensitivity: G2/M > G1 > early S > late S)246, 247. Consequently, chemotherapy (such as paclitaxel (PTX) and docetaxel (DTX)) followed by radiotherapy and multifraction radiotherapy (e.g., conventional fractionation (CF), 1.8-2.5 Gy daily fractions, Monday to Friday treatment), might synchronize cells at sensitive phases (G2/M and G1 phase) for RT, and could partially help to improve the therapeutic benefit.

The metal-based NPs induce cell cycle arrest 248-250, which can be exploited to increase radiosensitivity as well as chemosensitivity of cancer cells. Roa et al. reported that glucose-capped AuNPs played a role in radiosensitizing the radioresistant human prostate carcinoma DU-145 cells 251. Additionally, the authors analyzed the effect of AuNPs on the cell cycle distribution of cancer cells with flow cytometry. The results indicated that pretreatment with AuNPs led to accumulation of cancer cells at the most radiosensitive G2/M phase of the cell cycle due to the activation of the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK). Likewise, data from other groups suggested that AuNPs-induced G2/M phase arrest might contribute to the radiation enhancement when combined with AuNPs 252-256. In contrast, we and several other groups showed that treatment with AuNPs did not result in accumulation of cells in the radiosensitive G2/M phase 12, 225, 257, 258. In this respect, AgNPs 259-262 and GdNPs 103 were also reported to arrest cancer cells at the G2/M phase.

Also, as mentioned earlier in subsection Gold-based nanoparticles, we have previously shown that exposure to ionizing radiation could delay the division of tumor cells, and improved the subsequent cellular uptake of nano-agents in cells.

DNA repair inhibition

Radiotherapy is known to elicit various types of DNA damage 263. After sensing DNA damage, cellular DNA damage-response (DDR) machinery executes DNA repair by homologous recombination (HR), nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) for DSBs, as well as other pathways. Failure to repair the damage would cause cell death. Thus, in combination with RT, inhibition of DNA repair can augment the killing of tumor cells 264.

Typically, ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage modes include single-strand breaks (SSBs), DSBs, DNA-protein cross-links, and base damages. Among them, DSBs are considered the principal lethal type for radiation-induced lesions due to their more irreparable nature 265. Some studies have shown that metal-based NanoEnhancers could increase the number of initial DSBs in DNA following irradiation when employing plasmid DNA and agarose gel electrophoresis 20. In spite of this, along with time progress, the variation in DNA repair (in terms of dynamic changes in DNA damage) during radiosensitization can also be evaluated by comet assay, Western blotting, or immunostaining. Phosphorylated histone variant γ-H2AX (phosphorylation at serine 139) and p53-binding protein 1 (53BP1) (DNA repair protein) are considered to be the earliest sensitive markers of DSBs and the conserved DSBs sensor, respectively 266. Therefore, immunostaining to monitor the dynamic DSBs number, the kinetics of γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci were employed to assess the effect of metal-based NanoEnhancers on the subsequent DNA repair after DSBs damage in RT 267.

As reviewed in previous sections, TiONts and germanium oxide (germania, GeO2) have been shown to decrease efficiency of DNA repair following irradiation, then sensitize cells 160, 243. Quantification of indirect γ-H2AX and 53BP1 foci through immunofluorescence assays revealed the impact of AuNPs on the DNA repair processes following X-ray exposure 225, 268. However, other reports suggested that AuNPs did not influence the DNA repair 258, 269. A recent study indicated that gadolinium-based AGuIX NPs affected neither the level of DSBs nor the kinetics or efficiency of their repair, while eliciting marked radiosensitizing and synergistic effects probably attributed to the NPs' location in the cytoplasm rather than the nucleus 270. Furthermore, repair of X-ray-induced DNA damage in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells was shown to be delayed in the presence of AgNPs, while X-ray-induced initial DNA damage was not affected. 271.

Autophagy, ER stress, and other biological mechanisms

Among the biological mechanisms underlying radiation enhancement in the presence of metal-based NanoEnhancers are autophagy and ER stress.

Autophagy plays a major role during cellular and environmental stress by facilitating nutrient recycling via lysosome-mediated degradation of damaged and dysfunctional organelles, proteins, and other cytoplasmic constituents and helps in maintaining the intracellular homeostasis 272, 273. This conserved catabolic process possesses both positive and negative regulatory capabilities and can promote tumor progression 274. Inhibition of autophagic responses in neoplastic cells induces the antineoplastic effect 275, 276. The inhibitors of autophagy include chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), which are being used in many active and recently completed clinical trials, especially in combination with other therapeutic modalities such as radiotherapy (NCT01469455, NCT01575782, NCT02432417, NCT02378532, and NCT01727531). Others include 3-methyladenine (3-MA) and wortmannin for established tumors. Radiation-induced autophagy represents one of the radioprotective mechanisms in cancer cells, while inducing autophagy in RT can also increase cell death 277. We also found that high-LET carbon ions could induce significant autophagy in tumor cells and CQ or 3-MA sensitized cancer cells to carbon ions, probably through inhibition of autophagic responses 278.

In the past decade, most studies indicated that metal-based NPs could be exploited as efficient activators for autophagy due to the cellular defense mechanism against NPs-induced stress 279. On the other hand, very few studies reported that the metal-based NPs were capable of mediating the inhibitory effects for autophagy. Herein, a few general examples of relevant studies on metal-based NanoEnhancers are presented with regard to inhibition and induction of autophagy.

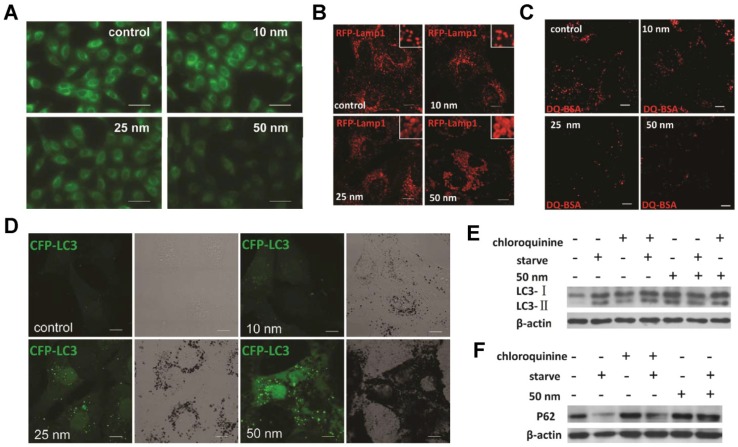

Liang's group reported that, similar to CQ alkalinization of lysosomal pH, AuNPs could block autophagy flux through size-dependent NPs uptake and lysosome impairment resulting in autophagosome accumulation 280(Fig. 7). Later, using in vitro assays and tumor-bearing mice, Wen's group verified that inhibition of AgNPs-induced autophagy in cancer cells improved their antineoplastic effect 281. Most interestingly, Gu's group recently described the important role of AgNPs-induced autophagy in the AgNPs' radiosensitization. Their studies implied that autophagy played a protective role in glioma cells treated with AgNPs, and inhibiting the protective autophagy led to the elevated levels of ROS and cell death (apoptosis)282, 283. These results have important implications for the application of metal-based NanoEnhancers in RT.

Figure 7.

AuNPs induce autophagosome accumulation through size-dependent nanoparticle uptake and lysosome impairment. (A) Effect of AuNPs on lysosome pH (representative fluorescence pictures of NRK cells (normal rat kidney) treated with AuNPs, then stained with LysoSensor Green DND-189 for evaluation of lysosomal acidity). Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Vacuoles induced by AuNP treatment are enlarged lysosomes (inset: close-up of the enlarged lysosomes). Scale bar = 10 μm. (C) DQ-BSA (derivative-quenched bovine serum albumin, a self-quenched lysosome degradation indicator) analysis of lysosomal proteolytic activity. Accumulation of fluorescence signal, generated from lysosomal proteolysis of DQ-BSA, was much lower in AuNP-treated cells. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Formation of CFP (cyan fluorescent protein)-LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3) dots (pseudocolored as green) in CFP-LC3 NRK cells treated with AuNPs. Left, confocal image; right, bright-field image. Scale bar = 10 μm. (E) LC3 turnover assay. The differences in LC3-I and LC3-II levels were compared by immunoblot analysis of cell lysates. (F) Degradation of the autophagy-specific substrate/polyubiquitin-binding protein p62/SQSTM1 (sequestosome 1) was detected by immunoblotting. Reproduced with permission from reference 280, copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

ER stress, originating from the endogenous/exogenous insults resulting in impaired protein folding, is considered another kind of cytoprotective pathway to re-establish ER homeostasis by the activation of unfolded protein response (UPR) 284. If ER stress cannot be reversed, cellular functions often deteriorate, finally leading to cell death 285. Therefore, targeting ER stress is considered a potential approach to cancer therapy 286, 287. Furthermore, the links between ER stress and autophagy have been substantiated 288, 289, and our laboratory has also presented some related data in our recent publications 290, 291.

It has been reported that metal-based NPs such as AuNPs, AgNPs, and zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs could induce ER stress 292-297. Various studies focused on using ER stress as a biomarker for nanotoxicological evaluation. However, Inanami's group evaluated the radiosensitizing potential of PEGylated nanogel containing AuNPs (GNG)298, 299. Their results suggested that GNG, which accumulated in the cytoplasm, sensitized murine squamous cell carcinoma SCCVII cells and human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells to X-rays through induction of apoptosis and inhibition of DSB repair partly as a consequence of GNG-mediated ER stress. Also, in human breast cancer MCF-7 and T-47D cells, AgNPs elicited apoptosis, probably resulting from the irreparable AgNPs-induced ER stress 300. Specifically, AgNPs caused accumulation and aggregation of misfolded proteins leading to ER stress and activation of UPR. On the other hand, non-cancerous human mammary epithelial MCF-10A cells were less sensitive to AgNPs. Also, no remarkable changes in the ER stress signaling pathway were observed in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells following treatment with AgNPs 301.

Recently, Kunjachan et al. reported that vessel-targeted AuNPs were able to disrupt tumor vascular by damaging the neo-endothelium and thus improving therapeutic efficacy of chemoradiotherapy while diminishing the toxicity of radiation and NPs 302. At the tissue level, this is an indirect and superior therapeutic modality. Also, the bystander effect could affect the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of metal-based NanoEnhancers through communication between cells via signaling molecules 233, 303. Of note is the fact that metal-based NanoEnhancers can react with thiols, for instance GSH, decreasing cellular defenses against oxidative stress and resulting in persistent damage 11.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the biological mechanisms for radiosensitization and synergistic effects of metal-based NanoEnhancers promote cell death by a variety of mechanisms, such as apoptosis, necrosis, mitotic catastrophe, autophagy, and senescence. No single process appears to dominate, rather a combination of these biological pathways appears to determine the fate of sensitized cells. Furthermore, metal-based NPs have been shown to also directly modulate cellular activity, function, and behavior 304. Developing innovative techniques and strategies, such as quantitative proteomics based on high-resolution mass spectrometry and systems biology, would be useful in evaluating biological contributions of metal-based NanoEnhancers in RT 305, 306. As an example, at the Emira laboratory of the SESAME (Synchrotron-light for Experimental Science and Application in the Middle East) synchrotron in Jordan, Yousef et al. investigated the cellular biochemical changes in F98 glioma rat cells employing the combination of X-rays and AGuIX NPs 97, 307. They determined the in situ chemical structure of biomolecules inside cells using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) microspectroscopy. In this study, notable spectral signature alterations in DNA, protein, and lipid regions were detected, which indicated changes in cellular function including elevated apoptosis.

Thus, in contrast to conventional chemical and biological agents used as radiosensitizers or for synergistic chemo-radiotherapy with specific biological targets, it is uncertain what the most critical target for the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of (high Z) metal-based nanoparticles/NanoEnhancers would be, because the primary targets depend on cellular and subcellular distribution and location of metal-based NanoEnhancers 118.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Metal-based nanoparticles can be employed to preferentially sensitize tumors to ionizing radiation due to the strong photoelectric absorption coefficient for high atomic number metallic elements and relative chemical inertness in cellular and subcellular systems. Compared to conventional chemical and biological agents such as those containing cisplatin, nitroimidazoles, and iodinated DNA targeting agents, metal-based “NanoEnhancers” are gaining credence as more ideal sensitizing agents 308, 309. The radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of NanoEnhancers are because of a multitude of physical, chemical, and biological parameters, such as the types of elements, the quantity and dose of ionizing radiation, as well as their size, shape, structure, coating, functionalization, concentration, pO2, and localization. Thus, metal-based nanoparticles, especially multimetallic nanocomposites, have shown great promise for multifunctional theranostic applications in radiation oncology.

The physical dose enhancement by the metal-based NanoEnhancers has been well described. However, experimentally observed sensitizer enhancement ratio (SER) and radiation dose enhancement factor (DEF) values for metal-based NanoEnhancers determined by colony forming assays or xenografts are significantly higher than those attributed to photoelectrons and Auger electrons predicted by Monte Carlo simulations. As indicated in Fig. 2, the amplification of radiation dose enhancement is likely mediated by spatio-temporally distributed ROS (mainly ·OH), which are produced in the early stages and can be evaluated by DCFH-DA (2',7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate) in living cell models and 3-CCA (coumarin-3-carboxylic acid) in aqueous buffered solutions. The complex biological processes underlying the sensitizing and synergistic effects of metal-based NanoEnhancers in radiotherapy include oxidative stress, cell cycle arrest, DNA repair inhibition, autophagy, and ER stress. So far, the biological synergies between radiotherapy and metal-based NanoEnhancers have not been well-addressed 310. In the future, elucidation of the role of biological contributions including modification of the tumor microenvironment, immune modulation 311, and cellular biochemical changes elicited only by NanoEnhancers 257 during the radiosensitization process would be helpful in better designing metal-based NanoEnhancers. Additionally, novel simulation methods based on more accurate models should be further developed to better calculate the physical dose enhancement by the metal-based NanoEnhancers 312. Although the excited electrons play a major role in inducing the production of ROS by ionizing water and oxygen molecules 313, the nanoscale mechanisms underlying metal-based NanoEnhancers-induced ROS production remain poorly understood. In recent years, surface-catalyzed reactions, including IONs' Haber-Weiss cycle and Fenton reaction, have been considered important induction mechanisms of the ROS cascade in the radiosensitization process of metal-based nanoparticles.

As for translating metal-based nanoparticles-enhanced radiation therapy into clinical practice, many interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary investigations in both in vitro and in vivo systems have provided promising results. However, at present, only two types of metal-based NanoEnhancers, multifunctional theranostic gadolinium-based AGuIX NPs and hafnia NBTXR3 NPs, are being specifically investigated for cancer radiotherapy in clinical trials. Although it has passed phase 1 trials, CYT-6091 pegylated AuNPs incorporating tumor necrosis factor-α has not been clinically investigated in combination with RT.

As discussed above, development of metal-based NanoEnhancers for clinical RT, especially multifunctional theranostic nanocomposites, is facing numerous challenges 227, 314, 315: physical & chemical characterizations, drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) screening, tissue targeting capability, biocompatibility and stability concerns, and regulatory, manufacturing, and immunogenic issues. For instance, the strategies of passive targeting suffer from some critical defects like the variation in tumor vascularization, vessel porosity, and drug expulsion 25. Additionally, to minimize potential health risks originating from nonspecific accumulation as well as long-term metabolic decomposition in the body, elimination of metal-based NanoEnhancers containing heavy or toxic metals from the body is a serious concern 234. So far, the assessment of metal-based NanoEnhancer toxicity has been inadequate. Detailed studies of biocompatibility and toxicity of these NPs are a must before they can be used in clinical practice 316.

It is increasingly being recognized that the lack of established and systematic experimental approaches is another principal obstacle for application of metal-based NanoEnhancers in cancer radiotherapy 20. Availability of accredited standards and methodologies for assessing the radiosensitizing and synergistic effects of metal-based NanoEnhancers would enable direct comparison of these investigations undertaken by various groups. Furthermore, the ability of metal-based NanoEnhancers to integrate current clinical principles of radiation oncology, such as administration route and frequency during the course of RT, would determine their acceptance by different stakeholders including physicians and patients 6.

Sometimes serendipity, but not luck, may play a role in anti-cancer drug discovery 317. Serendipitous discovery also requires scientific intuition, experience, knowledge, and critical thinking. Furthermore, an approach combining various disciplines of physics, biology, chemistry, pharmacology, medicine, and engineering as needed is necessary to remove the barriers and accelerate the difficult translation of preclinical studies on metal-based NanoEnhancers into new therapeutic strategies that would improve the outcome of RT at the individual patient level. This review was intended to provide an overview of the field as well as identify the areas to focus effort on.We hope that the continued efforts of both researchers and physicians will help design, develop, and apply the metal-based NanoEnhancers in cancer radiotherapy and will have a positive impact on therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

This publication was jointly supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2016YFC0904600, Ministry of Science and Technology of China), the National Key Technology Support Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2015BAI01B11, Ministry of Science and Technology of China), the NSFC-CAS Joint Fund for Research Based on Large-scaled Scientific Facilities (Grant No. U1532264, National Natural Science Foundation of China), and CAS “Light of West China” Program (Grant to Yan Liu, Chinese Academy of Sciences). The authors acknowledge Dr. Iqbal U. Ali for proof reading.

Abbreviations

- 3-CCA

coumarin-3-carboxylic acid

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- 53BP1

p53-binding protein 1

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- AgNPs

silver nanoparticles

- AGuIX

Activation and Guidance of Irradiation by X-ray

- AuNCs

gold nanoclusters

- AuNPs

gold nanoparticles

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma-2

- BiNPs

bismuth nanoparticles

- BRCA1

breast cancer 1

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- C18PMH

poly(maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene)

- c-Abl

cellular Abelson

- CAT

catalase

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinases

- CF

conventional fractionation

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- CLIONs

cross-linked dextran-coated IONs

- CQ

chloroquine

- CR

Čerenkov radiation

- CT

computed tomography

- CTCs

circulating tumor cells

- DCFH-DA

2',7'-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- DDR

DNA damage-response

- DDS

drug delivery systems

- DEF

radiation dose enhancement factor

- DMPK

drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N'',N'''-tetraacetic acid

- DOTAGA

1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1-glutaric anhydride-4,7,10-triacetic acid

- DQ-BSA

derivative-quenched bovine serum albumin

- DSBs

double-strand breaks

- DTDTPA

dithiolated derivative of the diethylenetriaminepentacetic acid

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- DTX

docetaxel

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared

- Gd-DTPA

gadopentetic acid

- Gd-NCT

gadolinium neutron-capture therapy

- GdNPs

gadolinium-based nanoparticles

- Gd-tex2+

Gd (III) texaphyrin

- GeNPs

germanium nanoparticles

- GNG

PEGylated nanogel containing AuNPs

- GSH

glutathione

- HCQ

hydroxychloroquine

- HEEpiC

human normal esophageal epithelial cells

- Hf:HAp NPs

hafnium-doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles

- HR

homologous recombination

- ICP-MS

inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry

- IGRT

image-guided radiotherapy

- IMRT