Abstract

Failure to rescue (FTR) is an outcome metric that reflects a center’s ability to prevent mortality after a major complication. Identifying the timing and location of FTR events could help target efforts to reduce FTR rates. We sought to characterize the timing and location of FTR occurrences at our center, hypothesizing that FTR rates would be highest early after injury and in settings of lower intensity of care. We used data, prospectively collected from 2009 to 2013, on patients ≥16 years old with minimum Abbreviated Injury Score ≥2 from a single institution. Major complications (per Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation definitions), mortality, and FTR rates were examined by location [prehospital, emergency department, operating room, intensive care unit (ICU), and interventional radiology] and by day post admission. Kruskal-Wallis and chi-squared tests were used to compare variables (P = 0.05). Major complications occurred in 899/6150 (14.6%) of patients [median age: 42, interquartile range (IQR): 25–57; 56% African American, 73% male, 76% blunt; median Injury Severity Score: 10, IQR: 5–17]. Of 899, 111 died (FTR = 12.4%). Compared with non-FTR cases, FTR cases had earlier complications (median day 1 (IQR: 0–4) versus 5 (IQR: 2–8), P < 0.001). FTR rates were highest in the prehospital (55%), emergency department (38%), and operating room (36%) settings, but the greatest number of FTR cases occurred in the ICU (52/111, 47%). FTR rates were highest early after injury, but the majority of cases occurred in the ICU. Efforts to reduce institutional FTR rates should focus on complications that occur in the ICU setting.

Failure to rescue (FTR) is the conditional probability of death after a major complication. Although this metric was originally defined in a cohort of patients undergoing elective surgery,1 FTR has since been studied in a number of surgical settings including emergency surgery2 and trauma.3–5 Consistent with FTR literature in other patient populations, Glance et al. found that although adjusted major complication rates did not vary significantly between high- and low-mortality centers, FTR rates were significantly higher at high-mortality trauma centers.4 This finding suggests that how centers respond to the occurrence of complications may have a greater influence on mortality than the absolute rates of complications alone. FTR rates are a particularly attractive target for quality improvement efforts as they appear to be influenced by structures and processes of care that may be subject to modification,6, 7 whereas the occurrence of complications is most strongly associated with patient-level factors that are beyond the control of trauma centers, such as age and comorbidities.

Despite the attractive properties of FTR as a metric, most of the literature on this subject has focused on the relationship between outcome metrics across populations of medical centers, with less attention paid to the occurrence of FTR events at individual centers. The location and timing of both deaths and complications8–12 have been well studied in trauma centers for many decades, but little information exists specific to FTR events. Understanding the breakdown and rates of specific complications that comprise the composite endpoint of FTR is important in the planning of countermeasures. A basic description of the epidemiology of FTR events would therefore be useful in informing efforts to reduce FTR rates in trauma.

Using prospectively collected data from an urban trauma center, we set out to describe the timing, location, and nature of FTR events. Under the assumption that increased monitoring might facilitate earlier recognition of complications, we hypothesized that complications leading to mortality would occur more frequently in settings with lower intensity of monitoring (such as the surgical wards) than in settings with higher intensity of monitoring [such as the surgical intensive care unit (ICU)]. Because mortality in trauma cohorts occurs most frequently within the first 48 hours,13 we also hypothesized that the majority of complications leading to death would occur in this period. Finally, to understand which complications were the largest drivers of the overall FTR rate at our institution, we sought to identify which groups of complications made the largest fractional contributions to the FTR rate.

Materials and Methods

Data collected prospectively for the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcomes Study from a single Level I trauma center, 2009 to 2013, were used. Inclusion criteria were age ≥16 years and a minimum Abbreviated Injury Scale score of ≥2 (moderate injury). Because elements of care may differ between trauma and nontrauma centers, transfers (both emergency department and inpatient) from outside hospitals were excluded. Additionally, patients with burn injury were excluded. Complications and pre-existing conditions (PEC) were defined according to Pennsylvania Trauma Systems Foundation definitions, available online at http://www.ptsf.org/index.php/resources. The admission Revised Trauma Score (RTS) was used as a proxy of physiologic derangement upon presentation. Major complications were defined as those used in the original published FTR work1 and those found to be associated with mortality in univariate logistic regression analysis with P < 0.1. This definition includes adult respiratory distress syndrome, acute respiratory failure, aspiration pneumonia, atelectasis, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), arrhythmia, coagulopathy, pleural effusion, hypothermia, postoperative hemorrhage, cardiopulmonary arrest, adverse drug reaction, acute kidney injury, hepatic failure, stroke, empyema, sepsis, septicemia, esophageal intubation, gastrointestinal bleeding, organ/nerve/vessel injury, decubitus ulcer, urinary tract infection, or wound infection. These complications were defined by the Pennsylvania Trauma Outcomes Study data dictionary definitions, and the occurrence, timing, and location of each complication was ascertained prospectively by trained nurse abstractors. FTR was defined as death after a major complication, and FTR rates were calculated with patients who suffered one or more major complications as the denominator. Patients who did not died after developing major complications were defined as “non-FTR” cases. As in the original FTR work by Silber et al. for patients sustaining more than one complication, the index complication was used to define entry into the FTR subset.1

Major complications, mortality, and FTR rates were calculated and examined by location [prehospital, emergency department, operating room (OR), ICU, interventional radiology suite, step-down unit, and ward] and by day post admission. To facilitate analysis, major complications were grouped into infectious (sepsis, septicemia, urinary tract infection, wound infection, empyema), cardiac (myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, cardiopulmonary arrest), pulmonary (adult respiratory distress syndrome, acute respiratory failure, atelectasis, aspiration pneumonia, pneumonia, pleural effusion), iatrogenic (pneumothorax, hypothermia, postoperative hemorrhage, adverse drug reaction, esophageal intubation, organ/nerve/vessel damage), hematologic (pulmonary embolism, DVT, coagulopathy), or other (stroke, acute kidney injury, acute hepatic failure, gastrointestinal bleeding) categories.

Baseline variables consisting of demographic variables (age, sex, race), mechanism of injury, physiologic derangement (as measured by RTS), and injury severity [as measured by Injury Severity Score (ISS)] were compared between FTR and non-FTR cases. The fractional contribution of each group of major complications to mortality was calculated as the overall number of complications in the group multiplied by the group-specific mortality. The distribution of the timing of the first major complication was examined graphically using histograms and statistically using the Mann-Whitney test. The overall number of FTR events as well as the FTR rate was examined by location. Categorical variables were compared using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, with two-sided P values set at ≤0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata IC 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 6081 patients meeting inclusion criteria with no exclusion criteria over the 3-year study period were as follows: median age 43 [interquartile range (IQR): 25–57], 56 per cent African American, 73 per cent male, 77 per cent blunt, and median ISS 10 (IQR: 5–17). In total, 420 deaths occurred during the study period, of which 309 (76%) occurred without preceding complications. Major complications occurred in 893/6081, for a major complication rate of 14.7 per cent. Of 893, 111 died, for an FTR rate of 12.4 per cent. Baseline variables between non-FTR and FTR patients are shown in Table 1. FTR patients were significantly more likely to be older, Caucasian, physiologically deranged by RTS, and have higher ISS relative to non-FTR patients. There was a greater preponderance of cardiac complications in FTR patients than in non-FTR patients, whereas non-FTR patients tended to have more infectious major complications.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Complications Grouped by Failure to Rescue

| Major Complications | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Non-FTR (n = 782) | FTR(n = 111) | ||

| Age (years) | 44 (27–63) | 51 (30–75) | 0.009 |

| Male gender | 585 (75%) | 85 (76%) | 0.70 |

| Race | 0.005 | ||

| African American | 414 (53%) | 47 (43%) | |

| Caucasian | 345 (45%) | 54 (50%) | |

| Asian | 15 (2%) | 7 (6%) | |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Blunt mechanism | 565 (72%) | 75 (68%) | 0.31 |

| RTS | 7.8 (7.1–7.8) | 6.9 (2.8–7.8) | <0.001 |

| ISS | 21 (11–30) | 26 (19–38) | <0.001 |

| Major complication category | <0.001 | ||

| Pulmonary | 273 (35%) | 31 (28%) | |

| Infectious | 198 (25%) | 4 (4%) | |

| Hematologic | 158 (20%) | 26 (23%) | |

| Cardiac | 79 (10%) | 37 (33%) | |

| Iatrogenic | 55 (7%) | 11 (10%) | |

| Other | 22 (3%) | 2 (2%) | |

Nonparametric continuous values expressed as median (IQR); categorical values are expressed as n (%). P values for Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables) or Mann-Whitney test (continuous variables).

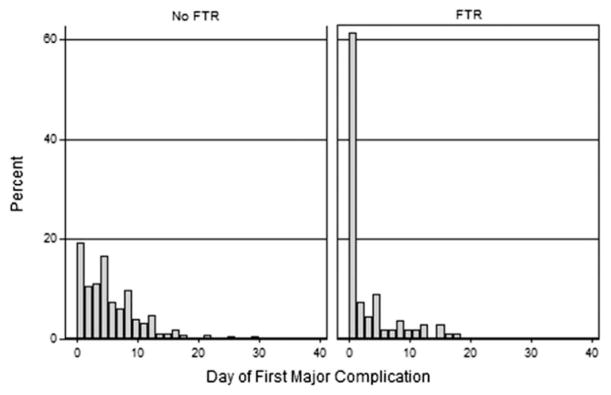

A histogram of the timing of the first major complication by FTR versus non-FTR patients is shown in Figure 1. In both groups, the distribution of the complications showed a heavy right skew, indicating that the majority of complications occurred early after admission. However, compared with non-FTR cases, FTR cases had earlier major complications (median day 1 (IQR: 0–4) versus 5 (IQR: 2–8), P < 0.001), with 60 per cent of FTR cases having the first major complication on the first day.

Fig. 1.

Day of the first major complication in patients suffering FTR versus no FTR.

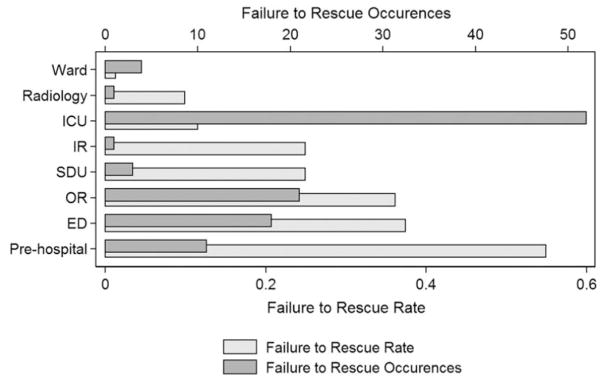

With respect to location of complications, ~50 per cent of index major complications occurred in the ICU in both the non-FTR and FTR groups. Cases of FTR were significantly more likely to have the antecedent major complication in the prehospital, emergency department, or OR setting (Fig. 2). Although the ICU was the most common location for a major complication leading to FTR, the overall rate of FTR after a major complication in the ICU was only 11.6 per cent. The highest rates of FTR followed major complications occurring in the prehospital setting (39%), the emergency department (36%), and the OR (42%).

Fig. 2.

FTR occurrences and rates by location of first major complication. ED, emergency department; IR, interventional radiology; SDU, step-down unit.

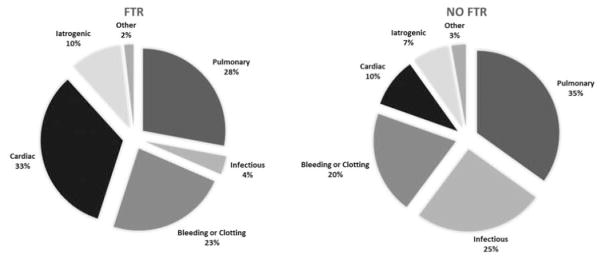

When considered by category (infectious, cardiac, pulmonary, iatrogenic, hematologic, and other causes) and location, several informative patterns emerged (Table 2). Mortality was high for cardiac complications in nearly all settings (mean: 33% mortality), ranking as the first or second most lethal complication in any specific setting. By contrast, infectious complications carried a relatively low risk of mortality in all settings and carried the lowest average risk of mortality (overall 1.9%). Pulmonary complications were by far the most common type of complication and generally conferred a relatively low risk of mortality (overall 10.2%). The fractional contributions of complications (by group) to the overall FTR rate are shown in Figure 3; together, pulmonary and cardiac complications were responsible for 68/111 (61%) of all FTR cases.

Table 2.

Rates of Failure to Rescue by Category and Location of First Major Complication

| Category | ICU (n = 447) | Ward (n = 294) | Operating Room (n = 58) | Trauma Bay (n = 46) | Other (n = 44) | Overall (n = 893) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Lived | Died | FTR Rate (%) |

Lived | Died | FTR Rate (%) |

Lived | Died | FTR Rate (%) |

Lived | Died | FTR Rate (%) |

Lived | Died | FTR Rate (%) |

Lived | Died | FTR Rate (%) |

|

| Pulmonary | 201 | 22 | 7.5 | 52 | 2 | 9.1 | 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 | 2 | 18.2 | 7 | 5 | 42.0 | 273 | 31 | 10.2 |

| Infectious | 60 | 2 | 8.8 | 128 | 1 | 1.2 | 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 1 | 14.3 | 198 | 4 | 1.9 |

| Hematologic | 60 | 10 | 14.3 | 77 | 0 | 0.0 | 12 | 12 | 50.0 | 4 | 2 | 33.3 | 5 | 2 | 28.6 | 158 | 26 | 14.2 |

| Cardiac | 34 | 15 | 30.6 | 17 | 1 | 5.6 | 7 | 5 | 41.7 | 12 | 10 | 45.5 | 6 | 6 | 50.0 | 76 | 37 | 32.7 |

| Iatrogenic | 25 | 1 | 3.9 | 10 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 4 | 28.6 | 3 | 4 | 57.0 | 7 | 2 | 22.2 | 55 | 11 | 16.7 |

| Other | 15 | 2 | 11.8 | 6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 22 | 2 | 8.3 |

| Total | 395 | 52 | 11.6 | 290 | 4 | 1.4 | 37 | 21 | 36.2 | 28 | 18 | 39.3 | 32 | 16 | 36.4 | 782 | 111 | 12.4 |

Because of the small overall numbers of occurrences, complications occurring in radiology, step-down units, interventional radiology, and prehospital setting were combined into an “other” category.

Fig. 3.

Classification of major complications in patients who survived (no FTR) and died (FTR).

Discussion

In this single-institution study of FTR deaths, we found that rates of death after major complications vary by time, location, and category of complication. Our findings are similar to previous findings on the timing of death in an analysis of ~2700 trauma patients by Demetriades et al., which demonstrated a high percentage of prehospital deaths (~37%) and deaths within the first 24 hours of admission (20.4% between 1 and 6 hours after arrival and 14.0% between 6 and 24 hours).13 Our methods differ from this study in that we only examined those deaths preceded by complications. In theory, our cohort of patients may offer more insight into targets for quality improvement because patients who die early after admission in the absence of complications may simply die because of overwhelming injury. Although we found that FTR rates were highest in the earliest settings after injury (prehospital, trauma bay, and OR), the greatest overall number of FTR events occurred in the ICU. Though the ICU had the largest absolute number of FTR events, its FTR rate (11.6%) was relatively low as many nonfatal complications also occurred in the ICU.

Certain types of complications are more likely to result in death than others. Considered by group, cardiac and pulmonary complications had the highest overall fractional contributions to FTR and together accounted for nearly two-thirds of all cases. Pulmonary complications were more common and less lethal, whereas cardiac complications were less common but more lethal. This finding is consistent with the work of Wakeam et al., which demonstrated a seven-fold increase in mortality rates after index complication of acute myocardial infarction compared with matched controls who did not suffer acute myocardial infarction.14 A better understanding of the dynamics between the nature of index complications and FTR is thus relevant in improving rescue in both elective surgery and trauma patients alike.

The FTR rate has been established as a key metric in understanding the relationship between mortality and complications across a wide variety of patient populations.1, 15–18 In elective surgical populations, rates of risk-adjusted major complications are similar between centers with high and low rates of mortality, whereas centers with higher mortality have been demonstrated to have higher rates of FTR.15 Early research on the use of FTR in trauma by Glance et al. demonstrated a similar phenomenon in the trauma population; although rates of major complications were similar between high- and low-mortality centers, centers with the lowest risk-adjusted mortality had similarly low FTR rates.4 In a similar study using the same dataset with different inclusion and exclusion criteria, Haas et al. found that both lower complication rates and lower FTR rates were associated with lower than expected mortality after severe injury.3

Although it seems intuitive that the best way to reduce mortality attributable to complications is to reduce the occurrence of complications in the first place, some evidence suggests that the answer may not be so simple. First, the occurrence of complications is strongly linked to patient factors such as age, injury severity, and comorbidities. Theses variable are not subject to modification by trauma centers, and as such at least some complications may be beyond the power of trauma centers to prevent. Second, even when risk factors for specific complications are both well understood and subject to modification, efforts to reduce rates of complications through quality improvement efforts do not always yield expected results. For example, timely and appropriate administration of prophylactic antibiotics is known to reduce the risk of surgical site infections, yet the results of compliance with Surgical Care Improvement Program measures directed at this target have been inconsistent.19–21 Likewise, pharmacologic prophylaxis is known to reduce the rates of venous thromboembolism after injury, but even “defect-free” pharmacoprophylaxis may still result in significant numbers of venous thromboembolism.22 Thus, at least some proportion of complications are not preventable, and expanding the focus to enhance the detection and management of complications may represent a higher yield approach to reducing mortality than trying to reduce complication rates alone.

Conceptually, two factors contribute to FTR: time (e.g., early recognition, early intervention) and appropriateness (e.g., appropriate treatment of the complication).15 Although this framework is useful in categorizing where to target efforts, such efforts cannot succeed without an understanding of the physical space in which they should be implemented. Because the majority of trauma FTR cases occur in the ICU, with only a minority occurring in the surgical wards, our findings suggest that increased vigilance on the surgical wards, via automated mechanisms such as Early Warning Systems (EWS), is unlikely to yield substantial reductions in the FTR rate. Failure to target EWS to settings with the highest likelihood of FTR events could in part explain why the use of EWS has not consistently been shown to reduce mortality.23, 24

Our study has several limitations. First, the results of this study are based on data from a single institution, and thus may not be broadly generalizable to other centers with differing patient populations and hospital characteristics. Larger, multi-institutional studies are necessary to confirm our findings. As in other FTR work, only the index major complication was used to define FTR, regardless of whether this complication was directly responsible for mortality. This practice is standard methodology for FTR research but may not fully account for the complex interplay between the initial complication, subsequent complications, and mortality. Although the data used for this study were collected in real time by trained nurse abstractors for the express purpose of studying complications and mortality after trauma, it is possible that some of the data may not accurately reflect the physiological process of developing a complication. For instance, the diagnosis of DVT is often made after a venous duplex is performed. In such a case, the DVT would be attributed to the time and location that the DVT was diagnosed, which may not in actuality reflect when and where it occurred. The gap between the development of a complication and the recognition of said complication is a known limitation of using complications as an endpoint of outcomes research, and reflects the clinical uncertainty inherent in the diagnosis of some of these events. It is also noteworthy that only 111/430 (24%) of deaths that occurred during the study period had complications before death and thus met the definition of FTR cases. Because injured patients may die because of injury before the occurrence of complications, the precedence rate (number of deaths preceded by complications) is expected to be lower than the nearly 100 per cent that would be expected in elective surgical cohorts in which the metric was described.25 The optimum method for handling these nonprecedented deaths is not currently defined.

In conclusion, we found significant variations in the location and timing of FTR events at our institution. Cardiac and pulmonary complications had the highest fractional contributions to FTR rate, with the majority of events occurring in the ICU. We believe that quality improvement initiatives to reduce institutional FTR rates should be informed by knowledge of the local epidemiology of FTR events. Based on our center’s epidemiology, efforts to reduce cardiac and pulmonary complications in the ICU would be expected to lead to the greatest overall reductions in the FTR rate.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by award number K12 HL 109009 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

The abstract for this manuscript was presented at the American Association of Surgery for Trauma 2015 Annual Meeting, September 10, 2015, Las Vegas, NV.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

J.J.C., E.C.E.-R., and D.N.H. contributed to the literature search, study design, data collection, data interpretation, writing, and critical revision. M.K.D., J.L.P., P.M.R., and D.J.W. contributed to the study design, writing, and critical revision.

References

- 1.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, et al. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care. 1992;30:615–29. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheetz KH, Krell RW, Englesbe MJ, et al. The importance of the first complication: understanding failure to rescue after emergent surgery in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haas B, Gomez D, Hemmila MR, et al. Prevention of complications and successful rescue of patients with serious complications: characteristics of high-performing trauma centers. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2011;70:575–82. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820e75a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glance LG, Dick AW, Meredith JW, et al. Variation in hospital complication rates and failure-to-rescue for trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2011;253:811–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318211d872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukur M, Habib F, Catino J, et al. Does unit designation matter? A dedicated trauma intensive care unit is associated with lower postinjury complication rates and death after major complication. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:920–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakeam E, Asafu-Adjei D, Ashley SW, et al. The association of intensivists with failure-to-rescue rates in outlier hospitals: results of a national survey of intensive care unit organizational characteristics. J Crit Care. 2014;29:930–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, et al. Hospital teaching intensity, patient race, and surgical outcomes. Arch Surg. 2009;144:113–20. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker CC, Oppenheimer L, Stephens B, et al. Epidemiology of trauma deaths. Am J Surg. 1980;140:144–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(80)90431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cales RH, Trunkey DD. Preventable trauma deaths. A review of trauma care systems development. JAMA. 1985;254:1059–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.254.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holbrook T, Hoyt D, Anderson J. The impact of major in-hospital complications on functional outcome and quality of life after trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:91–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mondello S, Cantrell A, Italiano D, et al. Complications of trauma patients admitted to the ICU in level I Academic Trauma Centers in the United States. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:473419. doi: 10.1155/2014/473419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoyt D, Coimbra R, Potenza B, et al. A twelve-year analysis of disease and provider complications on an organized level I trauma service: as good as it gets? J Trauma. 2003;54:26–36. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demetriades D, Murray J, Charalambides K, et al. Trauma fatalities: time and location of hospital deaths. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyder JA, Wakeam E, Adler JT, et al. Comparing preoperative targets to failure-to-rescue for surgical mortality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:1096–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Complications, failure to rescue, and mortality with major inpatient surgery in Medicare patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:1029–33. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e3181bef697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed EO, Butler R, Novick RJ. Failure-to-rescue rate as a measure of quality of care in a cardiac surgery recovery unit: a five-year study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menendez ME, Ring D. Failure to rescue after proximal femur fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29:e96–el02. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sammon JD, Pucheril D, Abdollah F, et al. Preventable mortality after common urological surgery: failing to rescue? BJU Int. 2015;115:666–74. doi: 10.1111/bju.12833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Billmoria KY, et al. Association of surgical care improvement project infection-related process measure compliance with risk-adjusted outcomes: implications for quality measurement. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:705–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholas LH, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD, et al. Hospital process compliance and surgical outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Surg. 2010;145:999–1004. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim LT. Surgical site infection: still waiting on the revolution. JAMA. 2011;305:1478–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haut ER, Lau BD, Kraus PS, et al. Preventability of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:912–5. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alam N, Hobbelink EL, van Tienhoven AJ, et al. The impact of the use of the Early Warning Score (EWS) on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2014;85:587–94. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith ME, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1454–65. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201403-102OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holena DN, Earl-Royal E, Delgado MK, et al. Failure to rescue in trauma: coming to terms with the second term. Injury. 2016;47:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]