Abstract

Purpose of Review

Adolescents, in particular those that are most disenfranchised, are increasingly at risk of acquiring HIV and, when acquiring HIV, have worse outcomes than adults. This article reviews the recent approaches to combination prevention aiming to optimize the HIV Prevention and HIV Treatment Continua.

Recent Findings

There are dramatic sociodemographic differences in the HIV epidemics in low and middle income countries (young women in sub-Saharan Africa) compared to high income countries (predominantly gay, bisexual, transgendered youth, especially Black and Latino youth). Researchers and clinicians are designing developmentally-tailored interventions that anticipate youths’ engagement with mobile technologies and build on the common features of evidence-based interventions that pre-date the use of antiretroviral therapies (ARV) for prevention and treatment.

Summary

Evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment programs that are cost-effective need to be broadly-diffused globally. Substantial investments must be made in understanding how to implement programs which have clinically-meaningful impact and continuously monitor intervention quality over time.

Keywords: HIV, adolescents, interventions, treatment and prevention

Introduction

Overview of the epidemiology of HIV among adolescents and key outcome markers

There are 36 million persons living with HIV (PLH) and 1.9 million new HIV cases annually [1]. About 34% of these are among adolescents aged 15 to 24 years, reflecting a 50% higher relative risk of infection than older adults [2]. There are now 2.1 million infected adolescents and young adults and young people reflect the only group in which the rate of infection continues to rise. Since 2005, there has been a 35% reduction in overall HIV-related mortality, yet among young people HIV mortality rates have increased by 50% from 2005 to 2012 [3].

Similar to adults, the pattern of the adolescent HIV epidemic is quite different in low and middle income countries (LMIC), compared to high income countries. However, in both LMIC and high income countries, those most disenfranchised are those most likely to be infected. In all countries, poverty is consistently linked to HIV, as is homelessness, survival sex, and intimate partner violence [4, 5].

Overwhelmingly, adolescent HIV is most prevalent in Africa, representing 66% of the HIV cases globally [6]. There, young women experience sexual debut earlier and often in relationships with older men. As a result, they are typically two to eight times more likely to be HIV infected compared to their same-age male peers [7]. Young women now reflect 72% of the epidemic among those aged 15–24 years old in Africa.

In contrast, adolescent HIV in high income countries is concentrated among gay, bisexual, and transgendered youth (GBTY) in large urban inner-cities. In the United States, among the highest risk subgroup, GBTY, it is Black and Latino youth who are most likely to become infected. In fact, more than 50% of Black gay, bisexual, and transgendered men can expect to become infected in the U.S. [8] – these are the only populations in high income counties experiencing a generalized HIV epidemic. Although to a lesser extent than in LMIC, adolescent women are at risk in high income countries. In the United States, women who live in poor, inner-city neighborhoods with high rates of substance abuse or who barter sex for survival, remain at risk. In other high income countries, refugee women, especially those without family supports, are also at high risk for HIV

Young HIV positive women, both in LMIC and in high income countries, face additional challenges. More than half of all babies are born to young women under the age of 24 years old (54%), and in LMIC, only about 44% of those who are seropositive are identified [1]. Perinatal transmission has plummeted with broad diffusion of strategies to Prevent-Mother-To-Child-Transmission (PMTCT), including access to lifelong ARV therapies – a policy adopted by the World Health Organization in 2013 [9] and greater HIV testing and treatment among young women in Africa [10]. Yet, pregnant women must also disclose their HIV status at childbirth, adhere to ARV to ensure viral suppression, get their infant tested for HIV at birth or within 10 weeks, use one feeding method for six months, and maintain their own adherence to HIV care and ARV lifelong. These are significant challenges and fewer than 25% complete these tasks [11]. Until a vaccine becomes available, PMTCT will continue to rely on adolescent women to adhere to a series of tasks.

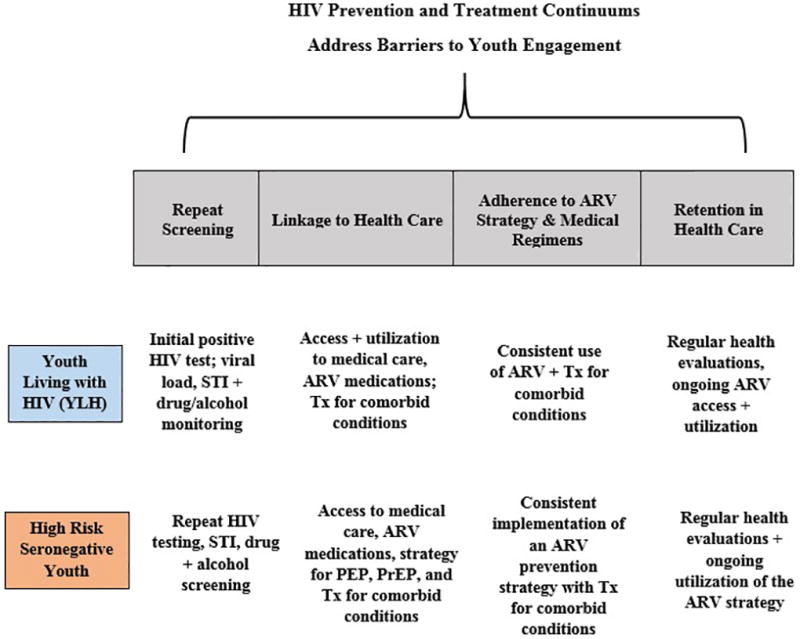

Similarly, the global HIV community has set the goal of stopping HIV by having 90% of persons living with HIV (PLH) knowing their serostatus, 90% of persons living with HIV linked to HIV care and receiving antiretroviral medications (ARV), and 90% of those infected becoming virally suppressed. We are far from reaching these goals, and youth living with HIV (YLH) are far less likely to achieve these goals than are adults [12, 13]. Progress is monitored globally by examining the HIV Treatment Continuum and the HIV Prevention Continuum. The tasks required for each of these Continuum have become increasingly similar over time, since ARV have now been demonstrated effective both for reducing infections among both seropositive and seronegative persons. Figure 1 summarizes the steps on both continua. While the specific screening measures and ARV regimens vary, the steps are similar for seropositive and seronegative youth. Both must be linked to health care on an ongoing basis; both must be tested repeatedly (one for viral load and the other tested for HIV), and ARV have advantages for both seronegative and seropositive young people. To stop HIV, these Continua must be optimized for young women in LMIC and for young GBTY in high income countries.

Figure 1.

Similarity of the HIV Prevention Continuum + HIV Treatment Continuum for Seropositive Youth Living with HIV (YLH) and High Risk Seronegative Youth (HRSY))

For HIV prevention, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is available for those at highest risk [14] and Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) – taking ARV after an exposure to HIV- is available for those who have been exposed to HIV. Yet, there have been few studies examining if adolescents will utilize or adhere to the medical care required to stop HIV transmission. There have been five demonstration projects in South Africa of PrEP which have found that adolescents need monthly health appointments, not quarterly, more ongoing support, and adherence is a challenge and remains low. Low adherence among seronegative persons creates the opportunity for treatment-resistant strains of HIV to be generated. Recent analyses with adolescents have demonstrated that either PrEP or PEP can be efficacious [15]. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is advocating use for young men at high risk of acquiring HIV.

Youth struggle with the HIV Treatment Cascade as well. In high income countries, about 70% of persons living with HIV know their HIV status and 44% are virally suppressed [16]. Using the United States as a prototype among high income countries, YLH are far less likely to link or be retained in care, compared to adults [17]. Only 36%–62% of YLH who know their serostatus are linked to medical care within 12 months of diagnosis [13, 18]. Young people are also more likely to drop-out from care than adults 25 years old and older [18, 19]. Existing studies suggest that few YLH remain in medical care more than a year, ensuring that ARV treatment adherence will also be low [20–22]. Retention in care and adherence to ARV are related, but adherence to ARV is the far more difficult task. Among one sample of YLH (atypically 72% female), initial ARV adherence was 69%; but by one year, ARV adherence was negligible as only 30% were retained in care [23]. In one ATN study of YLH, ARV adherence appeared to be about 50% [24]. While adherence rates as low as 70% may lead to viral suppression [25], youth are failing to hit that target.

Barriers to protecting adolescents from HIV risk and building resiliency

The subpopulations at highest risk for HIV, GBTY, experience great stigma. Uganda, Malaysia, and Singapore hang young men who are identified as having engaged in same-gender sexual contact [26, 27]. In Asian countries, shame is brought to the families of young GBTY. Fear of being ostracized, physical harm, and the desire to keep a strong social network are motivations which keep young men hiding their sexual orientation from their families and their friends. As the lifestyles of GBTY have become more accepted within a culture, it has been expected that there would be a similar reduction in stigma and prejudice against those at highest risk of acquiring HIV. For example, there are quasi-experimental data which indicate that in states with policies accepting of GBTY lifestyles, there are fewer mental health problems and less utilization of behavioral health care services [28, 29]. With less stigma associated with being GBTY, it may be easier to seek preventative services or treatment for HIV.

Risk behaviors typically cluster among youth in adolescents. Young people at risk for HIV are likely to also be at risk for mental health disorders, substance abuse disorders, interpersonal partner violence, and incarceration [30–33]. The risk concentrates among the low income inner city communities within high income nations. Some of these risks are a direct failure of policy initiatives. For example, the United States is currently coping with 1.2 million new opioid addicts; these addicts were created when new medications for pain control (OxyContin) were encouraged, with few regulations regarding use. As the street value of OxyContin has risen to more than $120 per pill, more and more drug addicts have been created – typically low income, white workers with chronic conditions. Without substantial interventions, the healthy development of addicted youth will be derailed. It will take many years for these young people to abandon or work their way out of a lifestyle characterized by risk into a life of building healthy daily routines.

Interventions likely to be effective

School is the typical setting which is able to reach all adolescents with preventive and therapeutic programs, at least up to ninth grade. After that, drop-out rates in inner-city schools require community-based approaches for contacting the youth at highest risk of acquiring HIV. Universal sex education and substance abuse prevention are interventions which may deter up to 15% of youth from experimenting or acquiring negative health habits that place them at risk for HIV. Consistently, the most successful school-based programs address adolescents at multiple levels: offering services at a school-based clinic, providing universal sex education, and building social support networks to stop stigma towards YLH and GBTY. In high-income countries, multi-faceted behavioral programs with both structural and intensive evidence-based health education classes have been demonstrated to delay sexual debut about six months and significantly increase condom use [34]. Yet, school-based programs have not been able to reduce sexually transmitted infections (STI) [35]. These programs are being phased out in high income countries, as these countries begin to rely upon PrEP and PEP and focus on the concentrated populations most affected by HIV: GBTY, homeless youth, incarcerated youth, youth with mental health problems and those bartering sex.

Even when receiving evidence-based prevention programs, the majority of adolescents experiment with sexual risk and drug abuse. Experimentation is a developmentally appropriate behavior for adolescents. This is a challenge for prevention programmers – should all experimenting youth be targeted or only those whose experimentation develops into a habit?

In addition, most prevention programs are based on female models of intervention. Counseling is an intervention model based on how women cope with stress - by tending and befriending others [36]. Men deal with stress with fighting or fleeing. As a result, HIV prevention programs based on counseling models have a much higher uptake of HIV prevention among young women than men. We need far more experimentation in our implementation models if we are to reach young men. Some examples of programs for young men focus on sports and vocational training [37].

In contrast to school-based approaches, HIV prevention has moved increasingly towards medical settings. However in the United States, 40% of adolescents do not utilize health care during adolescence, even when sick [38]. Black and Latino adolescents are even less likely to utilize medical care [39]. Furthermore, providers are often uncomfortable bringing up sexuality, even among GBTY. In fact, 40% of providers are uncomfortable bringing up getting the HPV vaccine, even with parents [40]. There are substantial number of training programs and materials targeted to physicians to increase their comfort in addressing sexuality, especially the needs of GBTY in medical settings. For youth at highest risk, adherence interventions to increase the uptake of PrEP and PEP are needed [41]. Yet, youth will need to be engaged in medical care in order to access these programs – a challenge given current patterns of medical care among adolescents.

The Centers for Disease Control and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration have identified the HIV intervention programs which have demonstrated efficacious [42]. Our group has rated the manuals of five, successful adolescent HIV interventions certified efficacious by the CDC to identify the common features of evidence-based interventions [43, 44]. All HIV evidence-based interventions accomplish the following tasks:

frame an issue (PrEP is a like a daily vitamin; live with HIV, not die);

communicate knowledge regarding HIV (e.g., PrEP can stop HIV acquisition) which must be implemented successfully in a youth’s life;

remove barriers to reaching your goal; and

build social support to sustain the behavior.

These functions can be accomplished through many different technologies and interpersonal strategies. By focusing on the common features of EBI, researchers, policy makers and community providers have one strategy to guide their tailoring, adaptation, and adoption of the EBI that must be fit to their community’s context. Both technological and interpersonal approaches should be now available to execute these common functions.

Technology provides an excellent vehicle for promoting health and connecting adolescents to the health care system [45]. Recent research shows that 80% of youth own a personal media device, 98% go online daily, and 78% prefer cell phones as their mode of communication [46–48]. Most youth own a cell phone and the percentage increases with age [49]. Many of today’s interventions support YLH to receive automated intervention strategies as a low intensity and a relatively low cost intervention. Mobile and social media strategies are used to support YLH to become virally suppressed and seronegative GBTY adhere to a strategy to protect themselves and others. We call the approach an Automated Messaging and Monitoring Intervention (AMMI): the intervention has a set of core functions, multiple delivery formats, and is tailored to meet the goals outlined in either the HIV Prevention Continuum or the HIV Prevention Continuum. Youth receive a daily email or text message which is theoretically-based and aimed to encouraging the targeted outcomes. There is substantial evidence that technology-based interventions are valid and useful [50]. For example, in the US, 89% of adolescents use text messages and the monthly average number of text messages sent and received is 2,899 texts [45] . The rates of texting are similar across income, ethnic and racial backgrounds, reducing health disparities in intervention uptake [50]. Reviews of text interventions have found that text messages increase ARV adherence [50–54] as well as adherence to other chronic disease medical regimens [55]. Text messages are efficacious to change both the health-seeking and adherence behaviors of YLH and to reduce sexual and drug use behaviors of high-risk youth [56–59].

Weekly, a probe asks for habits of daily living that week – this automated query is a way to encourage self-management – again, an evidence-based strategy [60–63]. Self-management of daily routines between clinical visits is a basic skill necessary for every chronic health condition. Monitoring one’s own behavior, in particular, is a strategy that has been repeatedly found to improve self-management [64–66]. Self-monitoring includes active observation and recording of behaviors, emotional states, and their determinants and effects-a core element of self-regulation [66–68]. Finally, social media is an additional component of our AMMI strategy. Social media is used by 73% of American youth, with 24% of youth posting daily [45]. Multiple studies of the social networks of adolescents indicate that youth can be engaged with mobile strategies [69–71]. This is just one potential vehicle to harness technology for improving HIV outcomes among youth: apps, social media accounts, geo-fenced events which focus on promoting health, and games are alternative technology strategies which can be useful and are currently being studied.

Conclusion

In summary, there are many efficacious approaches to enhancing the HIV Prevention and Treatment Continua, however, the evidence of efficacy of HIV interventions with adolescents remains in the era prior to PrEP and PEP. Novel intervention strategies must be identified, especially those that are likely to reach young men to expand our understanding of how to improve the reach and impact of HIV interventions to address PrEP, PEP, and to optimize the HIV Prevention and the HIV Treatment Continua.

Key points.

Adolescents continue to become infected at increasingly higher rates, unlike adults.

Fewer adolescents with HIV are linked to care and fewer are adherent to medications.

Girls in Africa, but gay, bisexual, and transgendered youth in high income countries are at highest risk for HIV.

Lessons from early HIV prevention and treatment interventions should be applied in the era of PEP, PrEP, and mobile technologies.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support and Sponsorship: Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Research Program Grant (NIH grant U19HD089886), NIH grants R24AA022919, R01DA038675, R01MH111391, R01AA017104, P30MH058107, and CFAR (5930AI028697)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.WHO, Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. World Health Organization Geneva; Switzerland: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Preventing HIV/AIDS in Young People: A systematic Review of the Evidence From Developing Countries. World Health Organization Geneva; Switzerland: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **3.Wood SM, Dowshen N, Lowenthal E. Time to Improve the Global Human Immunodeficiency Virus/AIDS Care Continuum for Adolescents: A Generation at Stake. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):619–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.58. This article discusses the youth HIV care continuum in the United States and the importance of addressing the HIV epidemic among adolescents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauermeister JA, et al. Where You Live Matters: Structural Correlates of HIV Risk Behavior Among Young Men Who Have Sex with Men in Metro Detroit. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(12):2358–2369. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatcher AM, et al. Bidirectional links between HIV and intimate partner violence in pregnancy: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:19233. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health & Human Services. The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; Washington, D.C.: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.UN Women. World AIDS Day Statement: For young women, inequality is deadly. United Nations: New York, NY: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lifetime Risk of HIV Diagnosis. Atlanta, GA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. World Health Organization Geneva; Switzerland: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson LF, et al. Rates of HIV testing and diagnosis in South Africa: successes and challenges. AIDS. 2015;29(11):1401–9. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.le Roux IM, et al. Outcomes of Home Visits for Pregnant Mothers and their Infants: a Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1461. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283601b53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner EM, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanoni BC, Mayer KH. The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: exaggerated health disparities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(3):128–35. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States - 2014. Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thigpen MC, et al. IAS. Rome, Italy: 2011. Daily oral antiretroviral use for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active young adults in Botswana: results from the TDF2 study. [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS. Ending AIDS: Progress Towards the 90-90-90 Targets. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner E, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall HI, Holtgrave DR, Maulsby C. HIV transmission rates from persons living with HIV who are aware and unaware of their infection. Aids. 2012;26(7):893–896. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328351f73f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner JM, et al. Zinc supplementation and psychosocial stimulation: Effects on the development of undernourished Jamaican children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82(2):399–405. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belzer ME, et al. Antiretroviral adherence issues among HIV-positive adolescents and young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25(5):316–319. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrand R, Ford N, Kranzer K. Maximising the benefits of home-based HIV testing. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(1):E4–E5. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garofalo R, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Personalized Text Message Reminders to Promote Medication Adherence Among HIV-Positive Adolescents and Young Adults. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy DA, et al. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence among adolescents infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(8):764–70. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez MI, et al. Profiles of Risk Among HIV-Infected Youth in Clinic Settings. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):918–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0876-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(7):939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A Bill for an Act Entitled the Anti Homosexuality Act. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Human Rights Watch. Discrimination Based on Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity. 2017 Available from: https://www.hrw.org/

- 28.Raifman J, et al. Difference-in-Differences Analysis of the Association Between State Same-Sex Marriage Policies and Adolescent Suicide Attempts. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(4):350–356. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Badgett MVL, et al. The Relationship between LGBT Inlcusion and Economic Development: An Analysis of Emerging Economies. Los Angeles: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- *30.Woollett N, et al. Identifying risks for mental health problems in HIV positive adolescents accessing HIV treatment in Johannesburg. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2017;29(1):11–26. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2017.1283320. This study identifies risks for mental health problems in HIV positive adolescents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burton P, Ward CL, Artz L. The Optimus Study on child abuse, violence and neglect in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: The Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- *32.Mutumba M, et al. Changes in Substance Use Symptoms Across Adolescence in Youth Perinatally Infected with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1117–1128. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1468-9. This longitudinal study examines changes in substance use among perinatally HIV infected and perinatally exposed but HIV uninfected youth as they travel through adolescence. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *33.Abram KM, et al. Disparities in HIV/AIDS Risk Behaviors After Youth Leave Detention: A 14-Year Longitudinal Study. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0360. This longitudinal study demonstrates that prevalence of sex risk behaviors are much higher among deliquint youth after leaving denetion compared to the general public. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma ZQ, Fisher MA, Kuller LH. School-based HIV/AIDS education is associated with reduced risky sexual behaviors and better grades with gender and race/ethnicity differences. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(2):330–9. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirby D, Laris BA. Effective Curriculum-Based Sex and STD/HIV Education Programs for Adolescents. Child Development Perspectives. 2009;3(1):21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor SE. Tend and befriend biobehavioral bases of affiliation under stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(6):273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. Feasibility of Using Soccer and Job Training to Prevent Drug Abuse and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(9):1841–50. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irwin CE, et al. Preventive Care for Adolescents: Few Get Visits and Fewer Get Services. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):E565–E572. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilkey MB, et al. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Idele P, et al. Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS among adolescents: current status, inequities, and data gaps. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;(66 Suppl 2):S144–53. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Efforts to Address HIV, AIDS, and Viral Hepatitis. SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rotheram-Borus M, Ingram B, Swendeman D, Flannery D. Common Principles Embedded in Effective Adolescent HIV Prevention Programs. AIDS and Behavior. 2009 Febuary; doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9531-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swendeman D, Ingram BL, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: an integrative framework. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1321–34. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenhart A, et al. Social medica & mobile internet use among teens and young adults. In: P.R. Center, editor. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, D.C: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calear AL, et al. Adherence to the MoodGYM program: outcomes and predictors for an adolescent school-based population. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):338–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zullig LL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of providing personalised cardiovascular risk information to modify health behaviour. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2014;20(3):147–152. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14528446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montero-Marin J, et al. Expectations Among Patients and Health Professionals Regarding Web-Based Interventions for Depression in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2015;17(3) doi: 10.2196/jmir.3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Victoria R. Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8–18 Year-olds. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lester RT, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9755):1838–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belzer ME, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of a Cell Phone Support Intervention for Youth Living with HIV with Nonadherence to Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(6):338–45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horvath KJ, et al. Strategies to retain participants in a long-term HIV prevention randomized controlled trial: lessons from the MINTS-II study. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):469–79. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9957-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pop-Eleches C, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. Aids. 2011;25(6):825–834. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834380c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Finitsis DJ, Pellowski JA, Johnson BT. Text message intervention designs to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **55.Mbuagbaw L, et al. Mobile phone text messaging interventions for HIV and other chronic diseases: an overview of systematic reviews and framework for evidence transfer. BMC health services research. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0654-6. This article examines the global evidence supporting the use of text messaging as a tool to improve adherence to medication and attendance at scheduled appointments. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ybarra ML, et al. Iteratively Developing an mHealth HIV Prevention Program for Sexual Minority Adolescent Men. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dowshen N, et al. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: a pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levine D, et al. SEXINFO: a sexual health text messaging service for San Francisco youth. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):393–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kachur R, et al. In: Adolescents, technology and reducing risk for HIV, STDs and pregnancy. U.S.D.o.H.a.H. Services, editor. CDC; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60.DiClemente CC, Nidecker M, Bellack AS. Motivation and the stages of change among individuals with severe mental illness and substance abuse disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Berg CA, et al. Parental involvement and adolescents' diabetes management: the mediating role of self-efficacy and externalizing and internalizing behaviors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(3):329–39. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo J, Whittemore R, He GP. The relationship between diabetes self-management and metabolic control in youth with type 1 diabetes: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(11):2294–2310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mlunde LB, et al. A call for parental monitoring to improve condom use among secondary school students in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2012;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramanathan N, et al. Identifying preferences for mobile health applications for self-monitoring and self-management: Focus group findings from HIV-positive persons and young mothers. Int J Med Inform. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Free C, et al. The Effectiveness of Mobile-Health Technology-Based Health Behaviour Change or Disease Management Interventions for Health Care Consumers: A Systematic Review. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swendeman D, et al. Smartphone self-monitoring to support self-management among people living with HIV: perceived benefits and theory of change from a mixed-methods randomized pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;(69 Suppl 1):S80–91. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker A, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioural intervention for HIV prevention among injecting drug users. Aids. 1993;7(2):247–256. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199302000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snyder M, Gangestad S. On the Nature of Self-Monitoring - Matters of Assessment, Matters of Validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(1):125–139. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rice E, Barman-Adhikari A. Internet and Social Media Use as a Resource Among Homeless Youth. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2014;19(2):232–247. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Pro-social and problematic social network influences on HIV/AIDS risk behaviours among newly homeless youth in Los Angeles. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2007;19(5):697–704. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rice E, Milburn NG, Monro W. Social Networking Technology, Social Network Composition, and Reductions in Substance Use Among Homeless Adolescents. Prevention Science. 2011;12(1):80–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]