Short abstract

Background

No evidence of disease activity (NEDA; defined as no 12-week confirmed disability progression, no protocol-defined relapses, no new/enlarging T2 lesions and no T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions) using a fixed-study entry baseline is commonly used as a treatment outcome in multiple sclerosis (MS).

Objective

The objective of this paper is to assess the effect of ocrelizumab on NEDA using re-baselining analysis, and the predictive value of NEDA status.

Methods

NEDA was assessed in a modified intent-to-treat population (n = 1520) from the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II studies over various epochs in patients with relapsing MS receiving ocrelizumab (600 mg) or interferon beta-1a (IFN β‐1a; 44 μg).

Results

NEDA was increased with ocrelizumab vs IFN β-1a over 96 weeks by 75% (p < 0.001), from Week 0‒24 by 33% (p < 0.001) and from Week 24‒96 by 72% (p < 0.001). Among patients with disease activity during Weeks 0‒24, 66.4% vs 24.3% achieved NEDA during Weeks 24‒96 in the ocrelizumab and IFN β-1a groups (relative increase: 177%; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Superior efficacy with ocrelizumab compared with IFN β-1a was consistently seen in maintaining NEDA status in all epochs evaluated. By contrast with IFN β-1a, the majority of patients with disease activity early in the study subsequently attained NEDA status with ocrelizumab.

Keywords: NEDA, disease activity, relapse, disability progression, MRI activity

Introduction

No evidence of disease activity (NEDA) is a composite measure of the absence of confirmed disability worsening (as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)) and of clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures of disease activity in relapsing multiple sclerosis (RMS). NEDA was originally described in a post-hoc analysis of the placebo-controlled, two-year Phase III pivotal trial for natalizumab.1 NEDA has since been widely used in analyses of other disease-modifying therapies (DMTs),2‒9 and has been adopted as an outcome measure in RMS clinical trials.10–13 NEDA may provide a more sensitive and comprehensive measure of capturing overall treatment benefit and has been proposed as a primary endpoint in future pivotal Phase III clinical studies.14,15 NEDA is increasingly recognized as an important treatment goal for patients with RMS16 and has been shown to be informative in the prediction of long-term disability progression both independent of DMT type17 (cohort study) and in the core and extension periods of clinical trial patient populations.18

As a binary outcome, NEDA status and its failure are often driven by MRI components of the measure and hence are particularly influenced by the frequency of MRI assessments.8,14 The analysis of NEDA is also affected by the pharmacodynamics of the particular therapy assessed. Re-baselining, wherein a post-study baseline time point is utilized as the new baseline reference for subsequent assessment of disability worsening and disease activity, therefore may reflect a truer representation of a DMT’s steady state of efficacy16 unconfounded by any initial disease activity carried over from baseline and recent pre-baseline disease state.

B cells are a significant contributor to the pathogenesis of MS.19,20 CD20 is a cell-surface antigen expressed on pre-B cells, mature B cells and memory B cells, but not lymphoid stem cells and plasma cells.21‒23 Ocrelizumab is a recombinant, humanized monoclonal antibody that selectively depletes CD20-expressing B cells24,25 while preserving the capacity for B-cell reconstitution and maintaining pre-existing humoral immunity.26,27 In the two identical Phase III trials, OPERA I and OPERA II, ocrelizumab significantly reduced all individual components of NEDA compared with high-dose, high-frequency interferon beta-1a (IFN β‐1a) at Week 96 in patients with RMS.28 The objective of the current analyses was to assess the effect of ocrelizumab on the proportion of patients with NEDA and determine the predictive value of NEDA over time in multiple epochs across the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II studies.

Patients and methods

Trial design and patients

NEDA was determined in the pooled population of the two identical Phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group OPERA I and OPERA II trials (OPERA I/NCT01247324 and OPERA II/NCT01412333). The study protocol was approved by each center’s independent ethics committee. The study design was written in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all enrolled patients provided written informed consent. The OPERA I and OPERA II trials were deemed poolable based on their identical protocols and according to formal poolability testing results.28 Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were not different within each study arm or between studies. Study details have been reported previously.28 Key eligibility criteria included an age of 18 to 55 years, diagnosis of RMS (2010 revised McDonald criteria)29 and an EDSS score of 0 to 5.5 at screening. Patients were randomized (1:1) to receive either ocrelizumab 600 mg by intravenous infusion every 24 weeks or subcutaneous IFN β-1a three times per week at a dose of 44 μg throughout the 96-week treatment period (including a per-label incremental titration scheme in the first four weeks). Patients were stratified by region (United States (US) vs rest of world (ROW)) and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 and ≥4.0) in the randomization for OPERA I and OPERA II.

Clinical and MRI endpoints, including NEDA

EDSS scores were determined at screening, baseline and every 12 weeks: Confirmed disability progression (CDP) was defined as a ≥1-point increase in EDSS score from a baseline EDSS score of 0–5.5, or a 0.5-point increase in EDSS score from a baseline EDSS score greater than 5.5, sustained for at least 12 weeks (12-week CDP). Protocol-defined relapses were new or worsening neurological symptoms attributable to MS: Symptoms must (i) persist for greater than 24 hours, should not be attributable to confounding clinical factors, and be immediately preceded by a stable or improving neurological state for at least 30 days; and (ii) be accompanied by objective neurological worsening consistent with an increase of at least half a step on the EDSS scale, or two points on at least one of the appropriate Functional Systems Scores (FSSs), or one point on two or more of the appropriate FSSs. Brain MRI was performed at baseline and Weeks 24, 48 and 96; new or enlarging T2 lesions and/or T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions on any scan during the epoch investigated were considered evidence of MRI disease activity. NEDA status was defined as the combined absence of: protocol-defined relapses; 12-week CDP; new or enlarging T2 lesions; and T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions.

Statistical analyses

NEDA outcome was primarily assessed in a modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population over the controlled treatment phase (baseline to 96 weeks),28 which included all patients in the intent-to-treat population, but patients who discontinued treatment early for reasons other than lack of efficacy or death and had NEDA before early discontinuation were excluded. Further analyses evaluated the proportion of patients with NEDA for several epochs, including: Weeks 0–48; Weeks 48–96 (where all components of NEDA including 12-week CDP were re-baselined to Week 48); Weeks 0–24; Weeks 24–48 (where all components of NEDA including 12-week CDP were re-baselined to Week 24); and Weeks 24–96 (where all components of NEDA including 12-week CDP were re-baselined to Week 24). NEDA and its components were compared in patients treated with ocrelizumab with those receiving IFN β-1a in a post-hoc analysis using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by study, geographic region (US vs ROW) and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 vs ≥4.0). Patients who discontinued treatment early with at least one event (i.e. protocol-defined relapse, 12-week CDP, new or enlarging T2 lesion or T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesion) before early discontinuation were considered as having evidence of disease activity (EDA). Even if a patient did not report an event before early discontinuation, the patient was considered as having EDA if the reason for early discontinuation was lack of efficacy or death.

Probability of attaining or maintaining NEDA relative to earlier EDA or NEDA status, and the predictive value of NEDA status

Subgroups of patients by NEDA status in Weeks 0–24 were assessed for subsequent NEDA status in Weeks 24–96 and in Weeks 24–48. Similarly, subgroups of patients by NEDA status in Weeks 24–48 were assessed for subsequent NEDA status in Weeks 48–96. Using the pooled treatment arms, NEDA status in Weeks 0–48 was used to predict time to (i) first protocol-defined relapse, and (ii) first 12-week and 24-week CDP in Weeks 48–96, and was evaluated based on the Cox proportional hazard regression model which included the NEDA during Weeks 0–48 as a factor, stratified by study, geographical region (US vs ROW) and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 vs ≥4.0).

Results

Patient demographics and disease characteristics

In the OPERA I and OPERA II trials, the pooled intention-to-treat population comprised 1656 patients (IFN β-1a, n = 829; ocrelizumab, n = 827). The mITT reference population used for the NEDA analysis comprised 759 and 761 patients randomized to high-dose, high-frequency IFN β-1a and ocrelizumab, respectively. Detailed baseline demographics and disease characteristics of (i) the mITT population and (ii) patients with EDA and NEDA over 96 weeks are presented by treatment arm in Table 1. All major baseline covariates were balanced between treatment groups in the mITT population. Compared with patients who maintained NEDA over 96 weeks, patients with EDA across treatment groups had slightly more relapses recorded in the 12 months prior to baseline, a greater number of T1 gadolinium-enhanced lesions and a higher T2 lesion burden at baseline. The age and proportion of female patients were slightly lower in the EDA group. Baseline EDSS score, disease duration and normalized brain volume were similar between patients who maintained NEDA or experienced EDA events.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographics and disease characteristics of the total pooled mITT patient population, and of patients maintaining NEDA vs having EDA over 96 weeks.

| Baseline demographics and disease characteristics | Pooled mITT population |

Patients with NEDA |

Patients with EDA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFN β-1aN = 759 | OcrelizumabN = 761 | IFN β-1aN = 206 | OcrelizumabN = 363 | IFN β-1aN = 553 | OcrelizumabN = 398 | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 37.1 (9.2) | 37.2 (9.1) | 39.4 (9.3) | 38.4 (9.0) | 36.2 (9.0) | 36.1 (9.1) |

| Female, % (n) | 66.8 (507) | 64.8 (493) | 72.8 (150) | 67.5 (245) | 64.6 (357) | 62.3 (248) |

| Time since MS symptom onset, mean (SD), years | 6.4 (6.1) | 6.6 (6.1) | 6.1 (6.1) | 6.8 (6.3) | 6.5 (6.1) | 6.4 (5.9) |

| Time since MS diagnosis, mean (SD), years | 3.9 (4.8) | 3.9 (4.9) | 3.5 (4.8) | 4.1 (5.1) | 4.0 (4.9) | 3.8 (4.6) |

| Number of relapses in previous 12 months, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.7)a | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.7)b | 1.4 (0.7) |

| EDSS score, mean (SD) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.3) |

| MRI | ||||||

| Number of T1 Gd+ lesions, mean (SD) | 2.0 (5.2)c | 1.8 (4.7)d | 0.4 (1.4)e | 0.7 (1.8)f | 2.6 (5.9)g | 2.8 (6.1)h |

| Brain T2 hyperintense lesion volume, median (range), cm3 | 6.2 (0–76.1)i | 5.4 (0–96.0)j | 3.8 (0–60.2)k | 3.8 (0–96.0)l | 7.2 (0.1–76.1)m | 7.5 (0–83.2)n |

| Normalized brain volume, mean (SD), cm3 | 1499.8 (88.3)o | 1501.7 (88.1)p | 1502.3 (84.1)q | 1502.3 (90.3)r | 1498.9 (89.8)s | 1501.3 (86.2)t |

EDA: evidence of disease activity; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; Gd+: gadolinium-enhancing; IFN β-1a: interferon beta-1a; mITT: modified intent-to-treat; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MS: multiple sclerosis; NEDA: no evidence of disease activity; SD: standard deviation.

an = 757; bn = 551; cn = 752; dn = 753; en = 205; fn = 357; gn = 547; hn = 396; in = 754; jn = 756; kn = 205; ln = 359; mn=549; nn = 397; on = 749; pn = 754; qn = 204; rn = 357; sn = 545; tn = 397.

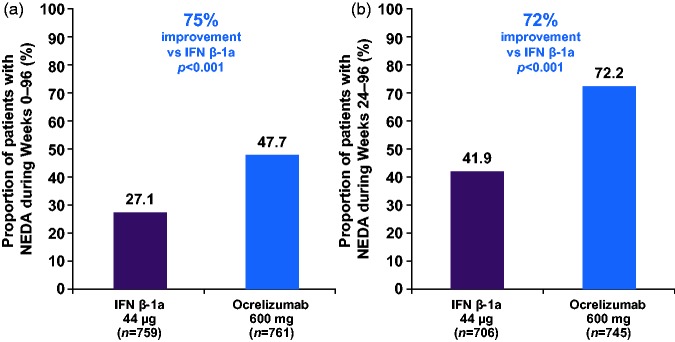

Overall NEDA (Week 0–96) and re-baselined NEDA (Weeks 24–96) status in the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II studies

In the pooled analyses of OPERA I and OPERA II, the relative proportion of patients with NEDA was increased by 75% (47.7% vs 27.1%; p < 0.001) with ocrelizumab compared with IFN β-1a over 96 weeks (Figure 1(a)).28 Following re-baselining at Week 24, the relative proportion of patients with NEDA was 72% higher (72.2% vs 41.9%; p < 0.001) with ocrelizumab compared with IFN β-1a during Weeks 24–96 (Figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with NEDA during (a) Weeks 0–96, and (b) during Weeks 24–96, re-baselined to Week 24.

Compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by study, geographic region (United States vs rest of world) and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 vs ≥4.0). Weeks 24–96: MRI at Week 48, Week 96 and unscheduled post-Week 24 scans prior to Week 96 are used in the definition of NEDA; this implies that analysis of the Week 24–96 epoch is based on two MRI scans. Weeks 24–96: Data were re-baselined to Week 24, i.e. all components of NEDA including 12-week CDP are defined relative to Week 24.

CDP: confirmed disability progression; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; IFN β-1a: interferon beta-1a; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NEDA: no evidence of disease activity.

During the 96-week epoch, a significant difference in the proportion of patients without disease activity was seen for each individual component of NEDA, including 12-week CDP, with ocrelizumab compared with IFN β-1a (p < 0.001; Table 2). This was reflected in the proportion of patients with no disability worsening and clinical disease activity (no 12-week CDP and no relapses: ocrelizumab 73.8% vs IFN β-1a 59.4%; p < 0.001) and no brain MRI measures of disease activity (no new or enlarging T2 lesions and no T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions: ocrelizumab 62.2% vs IFN β-1a 37.6%; p < 0.001; Table 2). Following re-baselining at Week 24, similar results were seen during Weeks 24–96 for the individual components of NEDA and the pairwise combination of clinical and MRI measures (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of patients with NEDA (and its individual components) in all epochs of the pooled OPERA I and OPERA II studies (mITT population).

| Study epoch (weeks) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–96 |

0–24 |

0–48 |

24–48a |

24–96a |

48–96b |

|||||||

| IFN β-1a | OCR | IFN β-1a | OCR | IFN β-1a | OCR | IFN β-1a | OCR | IFN β-1a | OCR | IFN β-1a | OCR | |

| Proportion of patients with NEDA, % | 27.1 | 47.7 | 45.7 | 60.8 | 34.9 | 54.6 | 59.0 | 85.8 | 41.9 | 72.2 | 57.3 | 81.8 |

| (n/N)c | (206/759) | (363/761) | (356/779) | (478/786) | (268/769) | (424/777) | (429/727) | (662/772) | (296/706) | (538/745) | (388/677) | (602/736) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.75 (1.53–2.01) | 1.33 (1.21–1.46) | 1.56 (1.39–1.76) | 1.45 (1.36–1.55) | 1.72 (1.56–1.90) | 1.43 (1.33–1.54) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with no CDP and no relapses, % | 59.4 | 73.8 | 83.2 | 88.9 | 70.8 | 81.8 | 81.1 | 89.1 | 66.2 | 76.5 | 76.3 | 83.3 |

| (n/N) | (431/726) | (556/753) | (624/750) | (676/760) | (522/737) | (619/757) | (579/714) | (673/755) | (461/696) | (569/744) | (514/674) | (613/736) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.25 (1.16–1.34) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 1.16 (1.09–1.22) | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | 1.16 (1.08–1.24) | 1.10 (1.04–1.15) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with no relapses, % | 67.3 | 80.0 | 87.3 | 92.5 | 77.4 | 87.6 | 87.2 | 94.4 | 75.1 | 85.4 | 83.9 | 89.4 |

| (n/N) | (511/759) | (609/761) | (680/779) | (727/786) | (595/769) | (681/777) | (634/727) | (729/772) | (530/706) | (636/745) | (568/677) | (659/737) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.19 (1.12–1.26) | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) | 1.08 (1.05–1.12) | 1.14 (1.08–1.20) | 1.07 (1.02–1.11) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with no CDP, % | 82.4 | 88.7 | 95.3 | 96.1 | 91.2 | 92.9 | 93.0 | 94.6 | 86.0 | 89.1 | 90.5 | 92.8 |

| (n/N) | (625/759) | (675/761) | (742/779) | (755/786) | (701/769) | (722/777) | (676/727) | (730/772) | (607/706) | (664/745) | (613/677) | (683/736) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.08 (1.03–1.12) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p = 0.42 | p = 0.18 | p = 0.19 | p = 0.057 | p = 0.082 | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with no brain MRI activity, % | 37.6 | 62.2 | 51.6 | 66.1 | 43.8 | 63.7 | 67.8 | 95.2 | 53.6 | 92.7 | 69.9 | 97.0 |

| (n/N) | (279/742) | (469/754) | (389/754) | (502/760) | (328/749) | (484/760) | (485/715) | (720/756) | (376/701) | (688/742) | (472/675) | (713/735) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.65 (1.48–1.84) | 1.28 (1.17–1.39) | 1.45 (1.32–1.60) | 1.40 (1.33–1.48) | 1.73 (1.61–1.86) | 1.39 (1.32–1.46) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with no new or enlarging T2 lesions, % | 39.1 | 62.8 | 54.0 | 67.4 | 46.7 | 64.9 | 69.7 | 95.9 | 56.1 | 94.5 | 71.5 | 98.2 |

| (n/N) | (297/759) | (478/761) | (421/779) | (530/786) | (359/769) | (504/777) | (506/727) | (740/772) | (396/706) | (704/745) | (484/677) | (723/736) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.60 (1.44–1.78) | 1.25 (1.15–1.35) | 1.39 (1.27–1.52) | 1.38 (1.31–1.45) | 1.68 (1.57–1.80) | 1.37 (1.31–1.44) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Proportion of patients with no T1 Gd+ lesions, % | 69.7 | 95.0 | 84.7 | 97.7 | 78.0 | 96.9 | 86.1 | 98.8 | 78.6 | 98.5 | 86.7 | 99.5 |

| (n/N) | (529/759) | (723/761) | (660/779) | (768/786) | (600/769) | (753/777) | (626/727) | (763/772) | (555/706) | (734/745) | (587/677) | (733/737) |

| Relative risk (CI) | 1.36 (1.30–1.43) | 1.15 (1.12–1.19) | 1.24 (1.19–1.29) | 1.15 (1.11–1.18) | 1.25 (1.21–1.30) | 1.15 (1.11–1.18) | ||||||

| p value | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||

CDP: confirmed disability progression; CI: confidence interval; Gd+: gadolinium-enhancing; IFN β-1a: interferon beta-1a; mITT: modified intent-to-treat; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NEDA: no evidence of disease activity; OCR: ocrelizumab.

aWeeks 24–48 and 24–96: Data were re-baselined to Week 24, i.e. all components of NEDA including 12-week CDP are defined relative to Week 24. bWeeks 48–96: Data were re-baselined to Week 48, i.e. all components of NEDA including 12-week CDP are defined relative to Week 48. cn/N: n is the number of patients maintaining “no event” status for respective endpoints in the table; proportions are based on N.

NEDA status analysis in all epochs of OPERA studies

Irrespective of the various epochs studied, a favorable outcome was seen with ocrelizumab compared with IFN β-1a; the relative proportion of patients with NEDA was 56% higher (54.6% vs 34.9%) with ocrelizumab during Weeks 0–48, 43% higher (81.8% vs 57.3%) during Weeks 48–96, 33% higher (60.8% vs 45.7%) during Weeks 0–24 and 45% higher (85.8% vs 59.0%) during Weeks 24–48 (all comparisons p < 0.001; Table 2). Sensitivity analyses of the relative proportion of patients with NEDA during Weeks 0–48 excluding T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at Week 24 revealed similar results to the original analysis (Supplementary Materials Table S1).

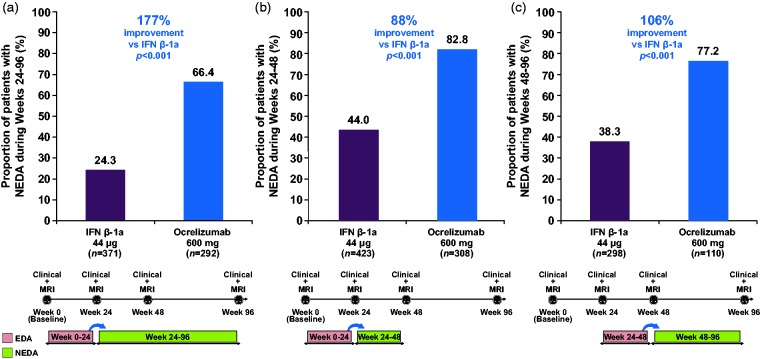

Probability of attaining or maintaining NEDA relative to earlier EDA or NEDA status

In the ocrelizumab and IFN β-1a groups respectively, 66.4% vs 24.3% of patients with EDA during Weeks 0–24 subsequently attained NEDA status during Weeks 24–96 (relative increase with ocrelizumab: 177%; p < 0.001, Figure 2(a)), and 82.8% vs 44.0% attained NEDA status during Weeks 24–48 (relative increase: 88%; p < 0.001, Figure 2(b)). Among patients with NEDA during Weeks 0–24, the proportion of patients who maintained NEDA during Weeks 24–96 was 75.9% vs 61.5% in the ocrelizumab and IFN β-1a groups, respectively (relative increase with ocrelizumab: 23%; p < 0.001), and during Weeks 24–48 the proportion was 87.6% vs 75.7% (relative increase with ocrelizumab: 16%; p < 0.001). Of patients with EDA during Weeks 24–48, in the ocrelizumab and IFN β-1a groups respectively, 77.2% vs 38.3% subsequently attained NEDA status during Weeks 48–96 (relative increase with ocrelizumab: 106%; p < 0.001, Figure 2(c)); among those patients with NEDA during Weeks 24–48, the proportion of patients who maintained NEDA during Weeks 48–96 was 82.5% vs 69.9% (relative increase with ocrelizumab: 18%; p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with NEDA during (a) Weeks 24–96, (b) Weeks 24–48 among patients with EDA in Weeks 0–24 and (c) Weeks 48–96 among patients with EDA in Weeks 24–48.

All components of NEDA including 12-week CDP are defined relative to Week 24 (a) and (b), and relative to Week 48 (c). Comparison using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by study, geographic region (United States vs rest of world) and baseline EDSS score (<4.0 vs ≥4.0).

CDP: confirmed disability progression; EDA: evidence of disease activity; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; IFN β-1a: interferon beta-1a; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NEDA: no evidence of disease activity; EDA: evidence of disease activity.

Predictive value of first-year NEDA status for subsequent risk of relapse and disability progression

When the treatment arms were pooled, patients with NEDA during Weeks 0–48 had a subsequent (Weeks 48–96) 53% risk reduction (hazard ratio (HR): 0.47; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.35–0.65; p < 0.001) in time to first relapse, a 36% risk reduction (HR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.44–0.94; p = 0.023) in time to first 12-week CDP, and a 39% risk reduction (HR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.39–0.95; p = 0.028) in time to first 24-week CDP, compared with those patients with EDA during Weeks 0–48.

Discussion

A higher proportion of patients had NEDA with ocrelizumab at the first MRI at Week 24 and in all epochs of the OPERA studies compared with high-dose, high-frequency IFN β-1a. Over two years, 48% of patients treated with ocrelizumab had NEDA, and as many as 72% had NEDA in Weeks 24–96 and 82% in Weeks 48–96, which is greater than that observed with other high-efficacy therapies in similar epochs.1,30,31 Absolute proportions of patients maintaining NEDA status should be considered in the context of the existence of a certain level of inherent background noise in the binary assessment of NEDA status because of potential false-positive detection of clinical EDA events, particularly for relapses, which may yield a treatment ceiling effect. Pairwise combinations of disease parameters in the clinical and MRI components of NEDA showed the consistent overall benefit of ocrelizumab compared with IFN β-1a, which was further reflected in all the individual components of NEDA, including confirmed disability progression. Compared with patients who maintained NEDA over 96 weeks, the patients with EDA across treatment groups had higher brain MRI activity at baseline as measured by T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions and higher T2 lesion burden, while no sizable difference was seen in pre-baseline relapse rate, and baseline EDSS score, disease duration and brain atrophy.

The early impact of ocrelizumab on MS disease activity was shown in a Phase II, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in patients with relapsing–remitting MS, in which ocrelizumab demonstrated a robust effect on MRI activity as early as Week 8 after initiating treatment.32 However, in order to represent the full efficacy of a DMT unconfounded by disease activity carried over during the first four to eight weeks from treatment initiation, particularly MRI related, a re-baselining approach at first available MRI has been suggested.3,14,33,34 Re-baselining MS disease parameters to Week 24 showed a 72% relative increase in the proportion of ocrelizumab-treated patients with NEDA from Weeks 24 to 96 compared with IFN β-1a-treated patients. Moving into the clinical practice setting, the optimal timing of re-baselining should reflect the anticipated timing for reaching complete DMT efficacy, to give a more reliable indication of subsequent drug failure. Conclusions from cross-trial comparisons are limited because of differences including comparators, patient populations, MRI techniques, frequency of assessments, analysis methods and definitions of NEDA. Nevertheless, irrespective of the epoch chosen (including baseline–Week 24, baseline–Week 48 and Weeks 24–96), greater absolute proportions of patients with NEDA were observed in the present analysis compared with those reported with other high-efficacy therapies for RMS.1,8,10,33

As noted above and reported in other studies,14,35 the lower frequency of MRI scans during Weeks 48–96 compared with the other epochs described may have influenced the proportions of patients maintaining NEDA. However, despite the longer duration and the additional (Week 48) scan within the NEDA analysis of the Week 24–96 epoch, the proportion of patients maintaining NEDA in the ocrelizumab group was higher (72%) from Weeks 24–96 than from Weeks 0–24 (61%), while the reverse was seen in the IFN β-1a group.

The majority of patients with EDA in Weeks 0–24 or Weeks 24–48 subsequently attained NEDA in Weeks 24–96 and Weeks 48–96 with ocrelizumab treatment, whereas such patients mainly continued to experience disease activity with IFN β‐1a. Delayed conversion to NEDA status in patients with EDA in the first few months of treatment has been similarly reported for other high-efficacy DMTs,1,31,33 findings that argue against the immediate discontinuation of such therapies based on early signs of EDA, although longer-term confirmation of maintenance of NEDA beyond Week 96 warrants further investigation in the open-label extension study.

When pooling treatment arms, NEDA status in the first year (Weeks 0–48) predicted a lower risk of relapse (Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to first relapse) and a lower risk of disability progression (as measured by 12- and 24-week CDP) in the second year (Weeks 48–96). The lower risk of subsequent relapse and disability worsening in patients with NEDA during the first year, combined with the high proportion of patients receiving ocrelizumab treatment maintaining NEDA in Year 2 in those patients with NEDA in Year 1, suggest NEDA status over the short term may predict longer-term benefits. Contradictory data have been reported on the prognostic value of NEDA status over two years in predicting future disability progression up to 10 years, at least in patient cohorts from real-world settings where the majority of patients were treated with self-injectable DMTs (interferons or glatiramer acetate).17,36,37 Few patients maintained NEDA over the long term in studies in which self-injectable DMTs were used (7.9% over seven years;17 0% over 10 years9). Conversely, NEDA was enhanced in patients over the long term in studies in which more effective DMTs were used (34% over seven years with natalizumab;38 40% over five years with alemtuzumab39). These data support the notion that, balanced with any risk associated with a particular DMT, NEDA may be a realizable long-term treatment goal for patients with RMS in the era of higher-efficacy therapies. Furthermore, re-baselining of NEDA status especially during the first year of DMT initiation might have value in clinical practice to assess early treatment response, and inform longer-term therapeutic decisions to optimize the control of MS disease activity.

Further evolution of the NEDA concept may include the future integration of brain volume loss, and research is ongoing to determine the optimal threshold(s) of annualized rates that may discriminate pathological atrophy at the individual patient level, while accounting for the effect of aging.9,40 Similarly, the incorporation of cognitive, ambulation and upper extremity function measures may enable a more comprehensive ascertainment of the absence of disability progression when assessing NEDA.

Overall, ocrelizumab consistently resulted in a profound reduction of clinical and subclinical disease activity compared with IFN β-1a in patients with RMS, as measured by NEDA across various epochs. Understanding the associations between NEDA and patient-reported outcomes is warranted to better inform the day-to-day relevance of maintaining NEDA status. Data from open-label extension studies will help determine whether NEDA maintained in the two-year OPERA studies will translate into sustained NEDA and enhanced protection against accrual of disability over the long term.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for No evidence of disease activity (NEDA) analysis by epochs in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with ocrelizumab vs interferon beta-1a by Eva Havrdová, Douglas L Arnold, Amit Bar-Or, Giancarlo Comi, Hans-Peter Hartung, Ludwig Kappos, Fred Lublin, Krzysztof Selmaj, Anthony Traboulsee, Shibeshih Belachew, Iain Bennett, Regine Buffels, Hideki Garren, Jian Han, Laura Julian, Julie Napieralski, Stephen L Hauser and Gavin Giovannoni in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and all the investigators for making the OPERA I and OPERA II trials possible; Stephen C. Reingold, Magnhild Sandberg-Wollheim, Scott Evans, Henry F. McFarland, Israel Steiner, Thomas Dörner and Frederik Barkhof for serving as members of the independent data and safety monitoring committee; Douglas Arnold, Amit Bar-Or, Giancarlo Comi, Gavin Giovannoni, Hans-Peter Hartung, Stephen Hauser, Bernhard Hemmer, Ludwig Kappos, Fred Lublin, Xavier Montalban, Kottil Rammohan, Krzysztof Selmaj, Anthony Traboulsee and Jerry Wolinsky for serving as members of the Study Steering Committee; and Gisèle von Büren for additional critical review of this manuscript and technical advice. Writing and editorial assistance for this manuscript was provided by Terence Smith of Articulate Science, UK, and funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: OPERA I/NCT01247324 and OPERA II/NCT01412333. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01247324https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01412333

Conflict of Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

Eva Havrdová has received honoraria/research support from Biogen, Czech Ministry of Education project PROGRES Q27/LF1, Sanofi Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis, Roche and Teva; and has participated in advisory boards for Actelion, Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Merck Serono, Novartis and Celgene.Douglas L Arnold reports personal fees for consulting from Acorda, Biogen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, MedImmune, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Receptos and Sanofi-Aventis; grants from Biogen and Novartis; and an equity interest in NeuroRx Research.Amit Bar-Or has received personal fees for consulting from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Genentech Inc, Biogen Idec, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck/EMD Serono, MedImmune, Mitsubishi Pharma, Ono Pharma, Receptos, Sanofi-Genzyme and Guthy-Jackson/GGF. He has also received research support from Novartis and Sanofi-Genzyme.Giancarlo Comi, in the past year, has received compensation for consulting services from Roche, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Genzyme, Merck, Excemed, Almirall, Chugai, Receptos and Forward Pharma, and received compensation for speaking activities from Roche, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Genzyme, Merck, Excemed, Almirall and Receptos.Hans-Peter Hartung has received honoraria for consulting, serving on steering committees and speaking at scientific symposia with approval by the Rector of Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf from Bayer, Biogen, GeNeuro, Genzyme, Merck Serono, MedImmune, Novartis, Octapharma, Opexa, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Teva and Sanofi.Ludwig Kappos’ institution, the University Hospital Basel, has received research support and payments that were used exclusively for research support for Prof Kappos’ activities as principal investigator and member or chair of planning and steering committees or advisory boards in trials sponsored by Actelion, Addex, Almirall, Bayer Health Care Pharmaceuticals, CLC Behring, Genentech Inc, GeNeuro SA, Genzyme, Merck Serono, Mitsubishi Pharma, Novartis, Octapharma, Ono Pharma, Pfizer, Receptos, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi, Santhera, Siemens, Teva, UCB and XenoPort; license fees for Neurostatus products; and research grants from the Swiss MS Society, the Swiss National Research Foundation, the European Union, the Gianni Rubatto Foundation, the Novartis Research Foundation and the Roche Research Foundation.Fred Lublin reports funding of research from Biogen Idec, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Teva Neuroscience Inc, Genzyme, Sanofi, Celgene, Transparency Life Sciences, the National Institutes of Health and National Multiple Sclerosis Society; consulting agreements/advisory boards/DSMB for Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono Inc, Novartis, Teva Neuroscience, Actelion, Sanofi, Acorda, Questcor/Mallinckrodt, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Genentech Inc, Celgene, Genzyme, MedImmune, Osmotica, XenoPort, Receptos, Forward Pharma, BBB Technologies and Akros; is co-chief editor for Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders; and has current financial interests/stock ownership in Cognition Pharmaceuticals Inc.Krzysztof Selmaj has received honoraria for advisory boards from Biogen, Novartis, Teva, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Merck, Synthon, Receptos and Genzyme.Anthony Traboulsee reports grants from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd during the conduct of the study; and grants and personal fees from Biogen, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi Genzyme and Chugai, outside the submitted work.Shibeshih Belachew is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.Iain Bennett is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.Regine Buffels is an employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.Hideki Garren is an employee and shareholder of Genentech Inc.Jian Han is an employee and shareholder of Genentech Inc.Laura Julian is an employee and shareholder of Genentech Inc.Julie Napieralski is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.Stephen L Hauser serves on the board of trustees for Neurona, and on scientific advisory boards for Annexon, Symbiotix and Bionure. He has also received travel reimbursement and writing assistance from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd for CD20-related meetings and presentations.Gavin Giovannoni has received honoraria from AbbVie, Bayer HealthCare, Biogen, Canbex Therapeutics, Five Prime Therapeutics, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, GW Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Merck Serono, Novartis, Protein Discovery Laboratories, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Synthon, Teva Neuroscience, UCB and Vertex; research grant support from Biogen, Ironwood, Merck Serono, Merz and Novartis; and compensation from Elsevier.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by financial support from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland for the study, data analysis and publication of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available for this article online.

References

- 1.Havrdová E, Galetta S, Hutchinson M, et al. Effect of natalizumab on clinical and radiological disease activity in multiple sclerosis: A retrospective analysis of the Natalizumab Safety and Efficacy in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis (AFFIRM) study. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovannoni G, Cook S, Rammohan K, et al. Sustained disease-activity-free status in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets in the CLARITY study: A post-hoc and subgroup analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prosperini L, Gianni C, Leonardi L, et al. Escalation to natalizumab or switching among immunomodulators in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2012; 18: 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovannoni G, Gold R, Kappos L, et al. Analysis of clinical and radiological disease activity-free status in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis treated with BG-12: Findings from the DEFINE study. J Neurol 2012; 259: S106. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lublin FD, Cofield SS, Cutter GR, et al. Randomized study combining interferon and glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2013; 73: 327–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nixon R, Bergvall N, Tomic D, et al. No evidence of disease activity: Indirect comparisons of oral therapies for the treatment of relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther 2014; 31: 1134–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Havrdová E, Giovannoni G, Stefoski D, et al. Disease-activity-free status in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis treated with daclizumab high-yield process in the SELECT study. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kappos L, De Stefano N, Freedman MS, et al. Inclusion of brain volume loss in a revised measure of ‘no evidence of disease activity’ (NEDA-4) in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2016; 22: 1297–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uher T, Havrdová E, Sobisek L, et al. Is no evidence of disease activity an achievable goal in MS patients on intramuscular interferon beta-1a treatment over long-term follow-up? Mult Scler 2017; 23: 242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen JA, Coles AJ, Arnold DL, et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: A randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1819–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ClinicalTrials.gov. Clinical disease activity with long term natalizumab treatment, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02677077 (2017, accessed 9 May 2017).

- 12.ClinicalTrials.gov. Plegridy observational program (POP), https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02230969 (2017, accessed 9 May 2017).

- 13.ClinicalTrials.gov. A study of ocrelizumab in comparison with interferon beta-1a (Rebif) in participants with relapsing multiple sclerosis, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01247324 (2016, accessed 9 May 2017).

- 14.Bevan CJ andCree BA.. Disease activity free status: A new end point for a new era in multiple sclerosis clinical research? JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 269–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beelke ME Antonini P andMurphy MF.. Evolving landscapes in multiple sclerosis research: Adaptive designs and novel endpoints. Mult Scler Demyelinating Disord 2016; 1: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovannoni G, Turner B, Gnanapavan S, et al. Is it time to target no evident disease activity (NEDA) in multiple sclerosis? Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015; 4: 329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotstein DL, Healy BC, Malik MT, et al. Evaluation of no evidence of disease activity in a 7-year longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72: 152–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappos L, De Stefano N, Chitnis T, et al. Predictive value of NEDA for disease outcomes over 6 years in patients with RRMS. In: 31st Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 October 2015, abstract no. 116.

- 19.Hauser SL. The Charcot Lecture | beating MS: A story of B cells, with twists and turns. Mult Scler 2015; 21: 8–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinzel S andWeber MS.. B cell-directed therapeutics in multiple sclerosis: Rationale and clinical evidence. CNS Drugs 2016; 30: 1137–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stashenko P, Nadler LM, Hardy R, et al. Characterization of a human B lymphocyte-specific antigen. J Immunol 1980; 125: 1678–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loken MR, Shah VO, Dattilio KL, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of human bone marrow. II. Normal B lymphocyte development. Blood 1987; 70: 1316–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tedder TF andEngel P.. CD20: A regulator of cell-cycle progression of B lymphocytes. Immunol Today 1994; 15: 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein C, Lammens A, Schäfer W, et al. Response to: Monoclonal antibodies targeting CD20. MAbs 2013; 5: 337–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genovese MC, Kaine JL, Lowenstein MB, et al. Ocrelizumab, a humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A phase I/II randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 2652–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin F andChan AC.. B cell immunobiology in disease: Evolving concepts from the clinic. Annu Rev Immunol 2006; 24: 467–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiLillo DJ, Hamaguchi Y, Ueda Y, et al. Maintenance of long-lived plasma cells and serological memory despite mature and memory B cell depletion during CD20 immunotherapy in mice. J Immunol 2008; 180: 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hauser SL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, et al. Ocrelizumab versus interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 221–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011; 69: 292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cree BAC, Kappos L, Freedman MS, et al. Long-term effects of fingolimod on NEDA by year of treatment. In: 31st Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 October 2015, abstract no. P627.

- 31.Prosperini L, Gianni C, Barletta V, et al. Predictors of freedom from disease activity in natalizumab treated-patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2012; 323: 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kappos L, Li D, Calabresi PA, et al. Ocrelizumab in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: A phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2011; 378: 1779–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kappos L, Havrdová E, Giovannoni G, et al. No evidence of disease activity in patients receiving daclizumab versus intramuscular interferon beta-1a for relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis in the DECIDE study. Mult Scler 2017; 23: 1736–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold DL, Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, et al. Effect of peginterferon beta-1a on MRI measures and achieving no evidence of disease activity: Results from a randomized controlled trial in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyle PK, Reder AT, Freedman MS, et al. Early MRI results and odds of attaining ‘no evidence of disease activity’ status in MS patients treated with interferon β-1a in the EVIDENCE study. J Neurol Sci 2017; 379: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Stefano N, Stromillo ML, Giorgio A, et al. Long-term assessment of no evidence of disease activity in relapsing–remitting MS. Neurology 2015; 85: 1722–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.University of California, San Francisco MS-EPIC Team, Cree BA, Gourraud PA, et al. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol 2016; 80: 499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prosperini L Fanelli F andPozzilli C.. Long-term assessment of no evidence of disease activity with natalizumab in relapsing multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2016; 364: 145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Havrdová E, Arnold DA, Cohen JA, et al. Durable efficacy of alemtuzumab on clinical outcomes over 5 years in treatment-naive patients with active relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis with most patients not receiving treatment for 4 years: CARE-MS I extension study. In: 31st Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 October 2015, oral presentation no. O152.

- 40.De Stefano N, Stromillo ML, Giorgio A, et al. Establishing pathological cut-offs of brain atrophy rates in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for No evidence of disease activity (NEDA) analysis by epochs in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with ocrelizumab vs interferon beta-1a by Eva Havrdová, Douglas L Arnold, Amit Bar-Or, Giancarlo Comi, Hans-Peter Hartung, Ludwig Kappos, Fred Lublin, Krzysztof Selmaj, Anthony Traboulsee, Shibeshih Belachew, Iain Bennett, Regine Buffels, Hideki Garren, Jian Han, Laura Julian, Julie Napieralski, Stephen L Hauser and Gavin Giovannoni in Multiple Sclerosis Journal – Experimental, Translational and Clinical