Abstract

Theories suggest that political ideology relates to cooperation, with conservatives being more likely to pursue selfish outcomes, and liberals more likely to pursue egalitarian outcomes. In study 1, we examine how political ideology and political party affiliation (Republican vs. Democrat) predict cooperation with a partner who self-identifies as Republican or Democrat in two samples before (n = 362) and after (n = 366) the 2012 US presidential election. Liberals show slightly more concern for their partners’ outcomes compared to conservatives (study 1), and in study 2 this relation is supported by a meta-analysis (r = .15). However, in study 1, political ideology did not relate to cooperation in general. Both Republicans and Democrats extend more cooperation to their in-group relative to the out-group, and this is explained by expectations of cooperation from in-group versus out-group members. We discuss the relation between political ideology and cooperation within and between groups.

Keywords: political ideology, in-group favoritism, cooperation, trust, social dominance orientation, right-wing authoritarianism

Conflict between political coalitions is a hallmark of vibrant democracies. To maintain a well-functioning democratic republic, individuals must negotiate with members of different political coalitions, make concessions, and ultimately cooperate. This process often unfolds in a suboptimal manner that can result in dramatic negative consequences to society, even to the point of government collapse. Indeed, coordinating and cooperating with individuals who have different goals, ideologies, and interests is one of the greatest challenges for politicians.

Given how critical cooperation between individuals of different ideologies is to a well-functioning government, surprisingly little research has examined cooperation between individuals of different political parties. Here we aim to contribute to this literature by examining how political ideology relates to (a) concern for others’ outcomes, (b) trust in others, (c) willingness to sacrifice self-interest to cooperate with others, and (d) in-group favoritism in terms of cooperation. Moreover, we consider the role of individual differences—social dominance orientation (SDO; Pratto et al. 1994) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA; Altemeyer 1998)—in cooperation within and between political coalitions. Below we outline ideas about when and how political ideology and coalitional membership may influence cooperation with in-group and out-group political coalition members.

Political Ideology and Cooperation

Political ideology is a “set of beliefs about the proper order of society and how it can be achieved” (Erikson and Tedin 2003, 64). An abundance of research finds that ideology varies on a left (liberal)–right (conservative) dimension (Bobbio 1996; for a review, see Jost, Federica, and Napier 2009). Liberals tend to support progressive change and egalitarianism, while conservatives support stability and find hierarchy acceptable. Consequently, ideology relates to desired behavioral options and outcomes during social decision making, with liberals preferring more egalitarian outcomes and conservatives accepting more unequal outcomes.

Political ideology may relate to cooperation via concerns about equality. Desire for equality (inequality aversion) can promote a willingness to cooperate with others (Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Van Lange 1999). Given that concern for equality is one of the defining features of liberal ideologies (Wetherell, Brandt, and Reyna 2013), liberals might be more motivated to sacrifice their own self-interest to establish equal and mutually beneficial outcomes in social interactions. Additionally, since conservative ideologies are associated with individualism and self-reliance (Feldman 1988; Sheldon and Nichols 2009), and these values promote individual concerns over collective concerns (e.g., Feldman and Zaller 1992), we expect that conservatives, compared to liberals, will be less concerned about others’ outcomes (in general) and so less willing to cooperate.

This reasoning has been examined in past research by considering how political ideology relates to social value orientation (SVO). SVO is a dispositional concern for self and others’ outcomes during interdependent decisions, and it has been found to predict cooperation across a wide range of situations (Balliet, Parks, and Joireman 2009; Van Lange et al. 1997). Previous research using United States (Sheldon and Nichols 2009) and Dutch and Italian (Van Lange et al. 2012) samples suggests that conservatives pursue more proself goals, while liberals pursue more prosocial goals. We provide an additional test of the hypothesis that liberals, compared to conservatives, will show greater concern for others’ outcomes (Hypothesis 1).

If political ideology relates to concern for others’ outcomes, then it should also predict a willingness to sacrifice self-interest to cooperate with others (see Van Lange, Schippers, and Balliet 2011). No research has yet tested this possibility, especially in situations where self-interest conflicts with collective interests, such as social dilemmas (see Dawes 1980). In a social dilemma, people are interdependent, and each person’s outcomes depend on both their own and others’ behavior. In social dilemmas, everyone receives a better outcome if each person cooperates, compared to when each person chooses not to cooperate. However, each person can gain the most for themselves by noncooperation and gaining the benefits from other’s cooperation (see Van Lange et al. 2014). Previous research has found that greater concern for equality and others’ outcomes positively relates to cooperation in social dilemma situations (Balliet, Parks, and Joireman 2009). Thus, liberals, compared to conservatives, are expected to cooperate more in social dilemmas (Hypothesis 2).

Mediating Processes: Egalitarianism and Trust

Political ideology may relate to both a general concern for others’ outcomes and cooperation through two mechanisms: (1) motivation to achieve equal outcomes and/or (2) (dis)trust that others will cooperate (see Pruitt and Kimmel 1977). As noted above, liberal ideologies promote egalitarian outcomes (Jost, Federica, and Napier 2009), and so egalitarian motives could mediate the relation between political ideology and concern for others’ outcomes (i.e., SVO; Hypothesis 3a). Similarly, the relation between political ideology and cooperation may be mediated by an egalitarian motive (Hypothesis 3b).

Since conservative ideology is characterized by beliefs that others are self-interested and competitive (i.e., the world is a competitive jungle) and that other people are dangerous and potentially harmful (i.e., belief in a dangerous world), conservatives might not expect that others will behave in a manner that promotes collective interests (Duckitt 2001; Duckitt and Parra 2004). In a social dilemma context, expectations of others’ cooperation can be considered a measure of trust in others, and these expectations strongly relate to one’s own cooperation (Balliet and Van Lange 2013). Thus, we predict that conservatives, compared to liberals, will expect less cooperation from others (Hypothesis 4a) and that expectations mediate the relation between political ideology and cooperation (Hypothesis 4b).

Political Coalitions and In-group Favoritism in Cooperation

People with common political ideologies cluster together to form political coalitions. In the contemporary US political landscape, individuals who are more ideologically liberal cluster into the Democratic coalition, and individuals who are more ideologically conservative cluster into the Republican coalition. Based on the arguments above, we would expect Democrats to be, on average, more cooperative than Republicans. However, previous theory and research suggest that people cooperate more with in-group members relative to out-group members and that this can largely be explained by expectations that other in-group members, compared to out-group members, are more willing to cooperate (Balliet, Wu, and De Dreu 2014; Yamagishi, Jin, and Kiyonari 1999). Therefore, we expect Democrats to be more cooperative with Democrats than with Republicans, and Republicans to be more cooperative with Republicans than with Democrats (Hypothesis 5a). We also predict that both Democrats and Republicans expect greater amounts of cooperation from in-group members than from out-group members (Hypothesis 5b) and that these expectations mediate in-group favoritism in cooperation (Hypothesis 5c). Thus, we expect that Democrats will discriminate in favor of in-group members to a similar extent as Republicans, despite the fact that Democrats may embrace more liberal ideologies, self-report relatively stronger concern for equality, and even be more cooperative with others in general, compared to Republicans.

SDO, RWA, and Cooperation

Political ideology may also relate to a tendency to discriminate in cooperation with in-group and out-group members. SDO is defined as “the basic desire to have one’s own primary in-group (however defined) be considered better than, superior to, and dominant over relevant out-groups” (Sidanius, Pratto, and Mitchell 1994, 153). This has been referred to as preference for egalitarian versus hierarchical relations between groups. Prior research has found that people high in SDO are more likely to discriminate between in-group and out-group members (Jost and Thompson 2000; Sidanius, Pratto, and Mitchell 1994). For example, Sidanius, Pratto, and Mitchell (1994) found that individuals high, compared to low, in SDO delivered greater rewards to in-group members, compared to out-group members. Thus, we predict that people high in SDO will show greater tendencies to cooperate with in-group members, compared to out-group members (Hypothesis 6).

RWA is characterized by authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism (Altemeyer 1981). People high on RWA tend to submit to authority and support aggressive actions toward out-groups (e.g., Benjamin 2006; Blass 1995). Moreover, RWA involves a motive to maintain social order, stability, cohesion, and security (e.g., Duckitt and Fisher 2003). Given that people from a different political coalition can pose a threat to social order—especially during a national presidential election—we also expect that people high in RWA will be more inclined to cooperate with in-group members, compared to out-group members (Hypothesis 7). Hence, directional predictions for both SDO and RWA (Hypotheses 6 and 7) are identical.

Overview of Studies

In study 1, we tested the hypotheses detailed above during the 2012 US presidential election, which pitted Democratic candidate Barak Obama against Republican candidate Mitt Romney. Past findings suggest that discrimination between groups is increased when individuals perceive that their group is threatened by an out-group (Campbell 1965; Sherif 1966). Here we study discrimination between members of different political coalitions in a time of intergroup conflict: during a national presidential election. Presidential elections can be largely considered as a type of zero-sum, a competitive context that involves a winner and a loser. Therefore, observing social interactions during a national election will allow us to study intergroup discrimination in cooperation in the context of intergroup conflict.

During the study, participants stated their political party affiliation and then interacted sequentially with four different partners (two Democratic partners and two Republican partners) in a social dilemma (i.e., a dyadic prisoner’s dilemma). They were told that both they and their partner were aware of each other’s party affiliation. Prior to each interaction, participants were asked how much cooperation they expected from their partner—this is commonly used as a measure of trust in others (see Balliet and Van Lange 2013). Afterward, we assessed SDO, RWA, and SVO. We conducted the study with two samples, one collected three days before the 2012 US presidential election and one collected three days after.

Study 2 further examines the relation between political orientation and concern for other’s outcomes during social interactions (i.e., SVO). Specifically, the meta-analysis can integrate the existing literature to provide an additional test of the hypothesis that individuals with liberal ideologies are generally more concerned about others’ outcomes, compared to individuals with conservative ideologies.

Study 1: Political Ideology, Trust, and Cooperation

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited in two waves through Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online labor market.1 The entire sample included 728 participants (M age = 32 years, SD age = 11; 45% Female). Wave 1 (n = 362) was conducted three days before the 2012 US national presidential election (Mitt Romney vs. Barak Obama), and wave 2 (n = 366) was conducted three days after the election. Most of the participants reported being White (78.8%), Asian (9.6%), or Black (6.5%). Across both samples, more participants identified as being Democrat (59.3%, n = 432) than Republican (20.5%, n = 149). Some participants reported identifying with a different political party or being politically independent (i.e., not having a party affiliation; 20.2%, n = 147). These sample characteristics are in line with previous research suggesting that Democrats are overrepresented among MTurk workers. The survey took less than twelve minutes on average to complete, and all participants were paid US$0.80 for their participation.

After enrolling in the study on MTurk, participants were directed to a website where they first read a brief description of the study and gave consent to participate. Next, they answered several questions about their political affiliation and ideology. Then they read a description of the prisoner’s dilemma and were told that they would interact with others currently online. Each participant answered four questions about their understanding of the prisoner’s dilemma. If they answered these questions incorrectly, they were redirected to the question and asked to give the correct response. Participants were allowed to proceed only if they answered the questions correctly.

Next, participants made a series of four decisions. Each participant interacted with two partners who were presented as conservative Republicans who would vote or voted for Romney and two partners who were presented as liberal Democrats who would vote or voted for Obama. Partner group membership (Republican vs. Democrat) was a counterbalanced within-subject manipulation. After making a decision in the prisoner’s dilemma with each partner, participants completed the three personality measures (SVO, SDO, and RWA) and answered a few demographic questions (age and ethnicity). Lastly, participants were debriefed about the purpose of the study.

Materials

Political ideology

Political ideology was measured with three items. Two items asked participants their agreement with the statements “when it comes to politics, I consider myself politically conservative” and “when it comes to politics, I consider myself politically liberal” on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly agree, 7 = strongly disagree). A third question asked, “how would you describe your political orientation” (1 = extremely left, 7 = extremely right). After reverse coding the first item, these three items were averaged to create an index of political ideology, with higher scores indicating a more conservative ideology (M = 3.23, SD = 1.61, α = .87). All means, standard deviations, and αs are reported in Table 1 and calculated from the entire sample (N = 728).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics, Alphas, and Zero-order Correlations.

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SVO | −689.83 | 997.48 | — | ||||||||

| 2. SDO | 2.29 | 1.27 | −.28 | .92 | |||||||

| 3. RWA | −1.11 | 1.29 | −.14 | .39 | .93 | ||||||

| 4. Political ideology | 3.23 | 1.61 | −.13 | .41 | .55 | .87 | |||||

| 5. Rep. versus Dem. | — | — | .08 | .39 | −.42 | −.63 | — | ||||

| 6. Exp. cooperation | 170.97 | 87.32 | .10 | .03 | .08 | .07 | −.11 | .73 | |||

| 7. Own cooperation | 192.90 | 108.55 | .30 | −.08 | −.03 | .02 | −.03 | .71 | .86 | ||

| 8. Diff. expect | −41.12 | 72.78 | −.09 | .29 | .33 | .43 | −.56 | .06 | −.03 | — | |

| 9. Diff. cooperation | −26.40 | 66.36 | −.05 | .25 | .28 | .38 | −.50 | .06 | .08 | .70 | — |

Note: N = 728 (N = 580 for correlations with Rep. vs. Dem.). The values at the diagonal line (if any) are the interitem correlations (αs) of the target scale. Correlations over r = .08 are significant at p < .05. SVO = social value orientation; SDO = social dominance orientation; RWA = right-wing authoritarianism; Rep. versus Dem. = Republicans (coded 1) versus Democrats (coded 2); Exp. cooperation = the total amount of expected cooperation from partner summed across all four trials of the prisoner’s dilemma; Own cooperation = the total amount of own cooperation summed across the four trials of the prisoner’s dilemma; Diff. expect = difference in the expected cooperation from Republican partner versus Democrat partner (a positive value indicates greater expected cooperation from a Republican, than Democrat, partner); Diff. cooperation = difference in one’s cooperation toward a Republican partner versus a Democrat partner (a positive value indicates greater cooperation with a Republican partner than Democrat partner).

We also asked participants what political party they identified with (Republican, Democrat, or other), whom they would prefer to be president, and whom they voted for in the election (Mitt Romney, Barak Obama, or did not vote). In the sample of participants before the election, we asked whom they intended to vote for. In the sample after the election, we also asked participants to indicate who won the election. All participants answered this correctly.

Prisoner’s dilemma

Participants made decisions in a two-person prisoner’s dilemma that has been used in previous research (e.g., Van Lange and Kuhlman 1994). For each decision, participants were given an endowment of 100 points and were asked how many points they would give to their interaction partner. Any points given to the other person were doubled. However, any points kept for themselves retained the same value. They were told that their partner was also endowed with the same amount of points and would make the same decision. This is a social dilemma because it is in each participant’s best interest to keep their points and to take any points that the other gives them. However, if each participant keeps their points, then each participant receives a worse outcome (100 points) compared to if each participant gives their entire endowment to their partner (200 points). Participants were asked to imagine that the points were valuable to both themselves and their interaction partners and that the more points they accumulated the better. They were also told to imagine that their partner felt the same way about these points.

Each participant made this decision for four trials, each of which involved an ostensibly different interaction partner (i.e., one of the two Democrats and one of the two Republicans). They were not told how many trials they would make the decision. For each trial, they were reassigned to a new partner (actually simulated) and were told this partner’s political ideology (Conservative or Liberal), political party affiliation (Republican or Democrat), and whom they voted for (or intended to vote for) in the 2012 presidential election (Romney or Obama). Each participant interacted with (a) two partners who were conservative, Republican, and voted for Romney; and (b) two partners who were liberal, Democrat, and voted for Obama. This information was provided at the top center of the screen. On the same screen including this information about their partner, participants reported how much they expected to receive from their partner (0 to 100 points) and then indicated how much they would give to their partner (0 to 100 points). These items were treated as measures of expected cooperation and own cooperation, respectively. Participants were not given feedback about their partner’s behavior. At the end of the study, participants were debriefed and paid for their participation.

SVO

Participants completed the nine-item triple dominance measure of SVO (Van Lange et al. 1997). For each item, participants indicate their preferred distribution of points allocated between themselves and another person. Each item contains three options that correspond to different social motives: (a) maximizing joint gain and equality (prosocials), (b) maximizing individual outcomes (individualists), and (c) maximizing relative outcomes between self and others (competitors). For example, in one item participants have a choice between (a) 510 points for self and 510 for the other (prosocials), (b) 560 points for self and 300 for the other (individualists), and (c) 510 points for self and 110 for the other (competitors). Traditionally, this scale has been used to categorize participants as prosocials or proselfs (individualists and competitors) if participants choose six or more options that either maximized joint gain and equality (prosocials) or maximized own outcomes or maximized relative outcomes between self and other (proselfs). Applying this procedure, the sample contained 70.1% prosocials and 23.6% proselfs (6.3% were unclassified). An alternative approach to using this scale is to compute the difference between the amount of points allocated to others and the amount of points allocated to self (see Balliet, Li, and Joireman 2011), with higher scores indicating more concern for others’ outcomes. This continuous measure of SVO correlates strongly with the dichotomous measure within the classifiable subsample (r = .96, p < .001) and will be used in the analyses reported below.

SDO

We used an eight-item measure of SDO (Jost and Thompson 2000; Pratto et al. 1994). Example items include “we should do what we can to equalize conditions for different groups” and “to get ahead in life, it is sometimes necessary to step on other groups.” Responses were given on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = very negative to 7 = very positive). After reverse scoring negatively keyed items, the overall scale had adequate internal reliability (α = .92). The SDO total score was computed by averaging across the eight items and higher scores indicate higher SDO.

RWA

This was measured with a fourteen-item scale (Altemeyer 1998). Example items include “our country desperately needs a mighty leader who will do what has to be done to destroy the radical new ways and sinfulness that are ruining us” and “everyone should have their own lifestyle, religious beliefs, and sexual preferences, even if it makes them different from everyone else”. Participants responded on a seven-point Likert-type scale (−3 = totally disagree, 3 = totally agree). After reverse coding the negatively keyed items, the total scale had adequate internal reliability (α = .93). Total RWA was computed by averaging across the fourteen items and higher scores indicate higher RWA.

Results

Political Ideology, Trust, and Cooperation (Hypotheses 1 to 4)

We first examined zero-order correlations between political ideology and SVO, trust in others (as measured by expectations of partner cooperation), and the total amount of cooperation across all trials in the prisoner’s dilemma. These correlations are displayed in Table 1. In support of Hypothesis 1, there was a small negative correlation between political ideology and SVO, r(725) = −.13, p < .001, meaning that higher levels of ideological conservatism were associated with lower concern with others’ outcomes. However, contrary to Hypothesis 2, this relation did not generalize to our measure of cooperation across the four trials of the prisoner’s dilemmas. Conservatives, compared to liberals, did not display different amounts of cooperation across the four trials of the prisoner’s dilemma, r(726) = .02, p = .58.

We expected that the relation between political ideology and concern for others’ outcomes (SVO) may be mediated by concern about equality in outcomes. We can use SDO as an index of concern about equality in outcomes, because SDO measures support for equality among individuals and groups. Consistent with existing theory and research, we observed a positive relation between political ideology and SDO, r(725) = .41, p < .001, which supports the notion that, with increasing conservatism, concern for equality in outcomes decreases. We examined if SDO mediated the relation between political ideology and SVO. Providing support for Hypothesis 3a, we found that the relation between political ideology and SVO was mediated by SDO (indirect effect = 69.32, 95% confidence interval [CI]: [45.32, 94.65]).2 Additionally, we hypothesized that the relation between political ideology and cooperation could be mediated by concern about equality in outcomes. However, given the null bivariate relationship between political ideology and cooperation, we found no support for Hypothesis 3b. Similarly, we did not find support for Hypotheses 4a and 4b, which suggested that conservatives would expect less cooperation from others and thus would be less cooperative themselves; that is, political ideology and expectations of partner cooperation were largely unrelated, r(724) = .07, p = .07.

Political Coalitions and In-group Favoritism (Hypothesis 5)

Cooperation

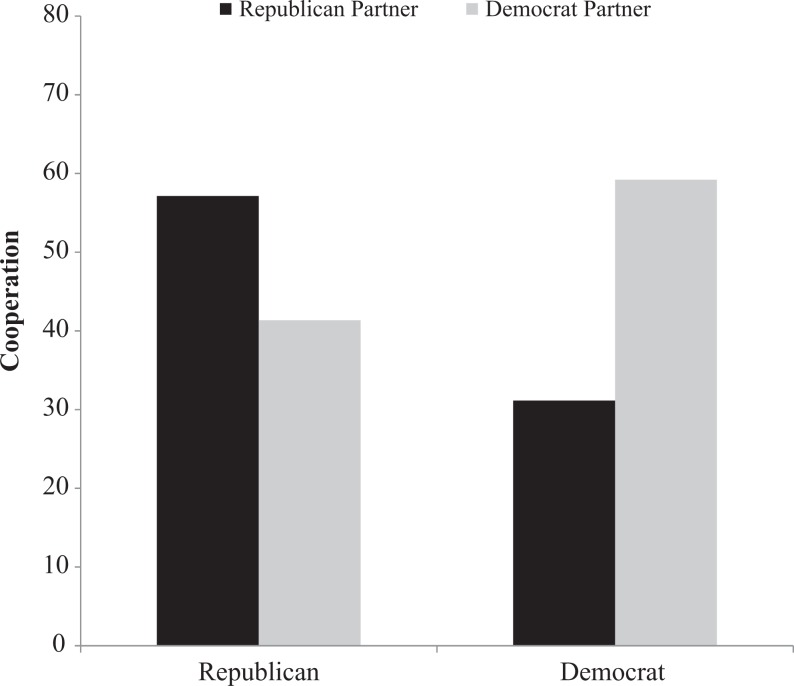

We next examined whether self-identified Democrats and Republicans tend to cooperate more with members of their in-group than their out-group. To do so, we conducted a mixed-model analysis of variance, including partner party affiliation (Republican vs. Democrat) as a within-subject factor and participant’s party affiliation (Republican vs. Democrat) as a between-subjects factor (see Table 2). When testing hypotheses about in-group favoritism in cooperation, we used participant’s self-identified party affiliation instead of political orientation (liberal vs. conservative), because some individuals hold liberal and conservative ideologies but identify with different political parties, such as Green or Libertarian, respectively. In support of Hypothesis 5a, we found a significant interaction between participant party affiliation and partner party affiliation, F(1, 579) = 193.05, p < .001, ηp 2 = .25. The interaction is displayed in Figure 1. Simple effect tests revealed that self-identified Republicans were more cooperative with a Republican partner (M = 57.13, SD = 31.37), compared to a Democrat partner (M = 41.36, SD = 33.03), F(1, 579) = 40.70, p < .001, d = 0.48. Similarly, self-identified Democrats were more cooperative with a Democrat partner (M = 59.21, SD = 28.85), compared to Republican partner (M = 35.15, SD = 31.61), F(1, 579) = 274.69, p < .001, d = −0.83.3 Additionally, Table 1 displays the correlation between political orientation and the difference score in one’s cooperation toward a Republican partner versus a Democrat partner. The significant positive correlation (r = .38, p < .001) indicates that politically conservative individuals display greater cooperation with a Republican partner than Democrat partner, while liberals tend to cooperate more with Democrats than Republicans.

Table 2.

Analysis of Variance Models Testing the Interaction between Own Political Party Affiliation and Partner Political Party Affiliation Predicting Cooperation (Model 1) and Expected Partner Cooperation (Model 2).

| Predictor | Cooperation (model 1) | Expected partner cooperation (model 2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ηp 2 | F | p | ηp 2 | |

| Own party affiliation | 0.65 | .419 | .00 | 7.22 | .007 | .01 |

| Partner party affiliation | 8.36 | .004 | .01 | 46.06 | <.001 | .07 |

| Own party × partner party | 193.05 | <.001 | .25 | 260.16 | <.001 | .31 |

Figure 1.

Participant political party affiliation and partner political party affiliation predicting own cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemmas.

Expectations of partner cooperation

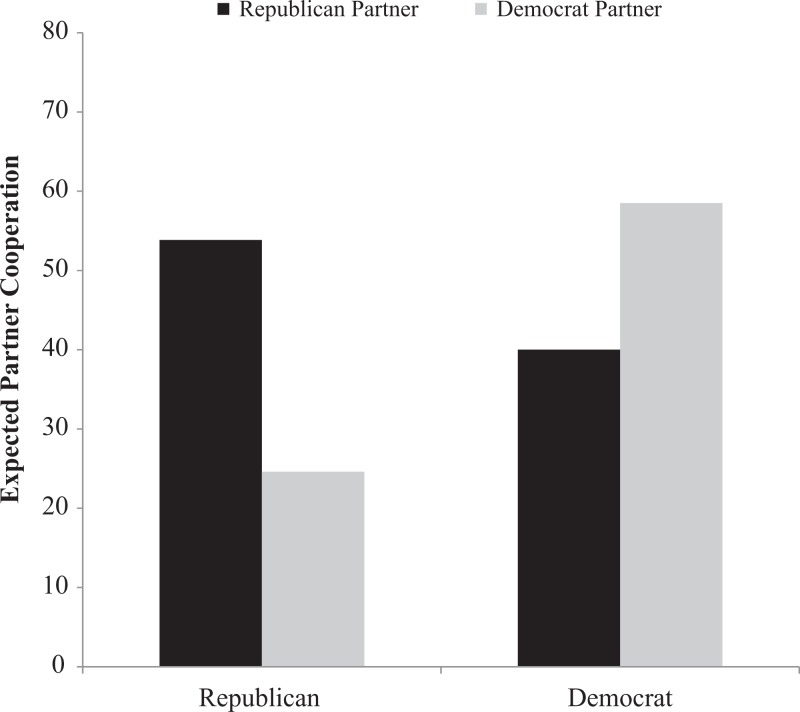

We tested the same model described above on expectations of partner cooperation. As displayed in Table 2, we found a similar pattern of results. Even controlling for whether participants identified as Democrats or Republicans, participants expected more cooperation from Democrats (M = 53.76, SD = 27.32) than from Republicans (M = 32.12, SD = 29.21), F(1, 578) = 46.05, p < .001, ηp 2 = .07.

We also found support for Hypothesis 5b, that people tended to expect more cooperation from members of their political party, F(1, 578) = 260.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .31 (Figure 2). Further simple effect analyses revealed that Republicans expected more cooperation from fellow Republicans (M = 53.85, SD = 28.54) compared to Democrats (M = 40.02, SD = 30.84), F(1, 578) = 29.37, p < .001, d = 0.37, and Democrats expected more cooperation from fellow Democrats (M = 58.50, SD = 24.28) compared with Republicans (M = 24.60, SD = 25.46), F(1, 578) = 29.37, p < .001, d = −1.19. Thus, both Democrats and Republicans tend to expect greater cooperation from their in-group compared to out-group.4

Figure 2.

Participant political party affiliation and partner political party affiliation predicting expected partner cooperation in the prisoner’s dilemmas.

We also hypothesized that expectations of partner cooperation would mediate the relation between participant political coalition identification and cooperation with in-group and out-group members (Hypothesis 5c). Applying the Preacher and Hayes (2004) method of testing mediation, we regressed the difference score in cooperation with a Republican partner and Democrat partner on self-identified own political party affiliation (Republican or Democrat; total effect = −40.09, p < .001). This effect was reduced when entering a mediating variable, the difference score in expected cooperation from a Republican partner and Democrat partner, to the model (direct effect = −13.24, p < .001). Specifically, we found that the difference score in expected cooperation from a Republican partner and Democrat partner partially mediated this relation (indirect effect = −26.85, 95% CI [−33.16, −21.10]). Results were unaffected when including individual differences (i.e., SVO, SDO, and RWA) as control variables. Thus, we find support for Hypothesis 5c that in-group favoritism in cooperation among political party members is mediated by trust in in-group, compared to out-group, members.

Table 1 also displays the correlation between political orientation and the difference score in expected partner cooperation from a Republican partner versus a Democrat partner. The significant positive correlation (r = .43, p < .001) indicates that politically conservative individuals expect greater cooperation from a Republican partner than Democrat partner, while liberals tend to expect more cooperation from Democrats than Republicans.

Political Ideology and In-group Favoritism (Hypotheses 6 and 7)

We hypothesized that both people high in SDO (Hypothesis 6) and RWA (Hypothesis 7) would display stronger in-group favoritism in cooperation. To test these hypotheses, we regressed the difference score in cooperation between Republicans and Democrats on participants’ political party identification, mean centered SDO and RWA, and the interaction between RWA and SDO with political party identification. If higher SDO and RWA relate to stronger discrimination in favor of the in-group, then these variables should interact with political party identification in predicting the difference score in cooperation. In this model, we only observed a significant effect of participant’s own political party identification, β = −.42, p < .001. Hence, SDO, RWA, and each of their interactions with the participant’s party identification did not have a significant relation with discrimination between Republicans and Democrats. Thus, we found no support for Hypotheses 6 and 7.

Study 2: Meta-analysis on Political Ideology and Concern for Others’ Outcomes

Study 1 replicates prior research that has found that political ideology relates to concern for others’ outcomes, as measured by SVO (e.g., Van Lange, Bekkers, Chirumbolo, and Leone 2012). Yet, the relation between ideology and SVO was small (r = −.13) and we did not find that this relation generalized to cooperation in the social dilemma. Therefore, we decided to conduct a meta-analysis of the known research on political orientation and SVO to get a more accurate assessment of the direction and magnitude of the effect size.

Methods

We searched for all studies that measured political orientation and SVO using PsycINFO and Google Scholar. We were only able to find five studies that examined this relation. Our first criterion is that each study included a measure of political orientation. Four studies measured political orientation (from conservative to liberal ideologies) and one study measured political party identification in the United States (Democrat vs. Republican). We also include the latter study in the overall meta-analysis, because in the United States political party identification relates strongly to political orientation. For example, in our study, Republicans were much more conservative than Democrats (r = −.63, p < .001). Importantly, excluding this study from the meta-analysis does not change the outcome of the meta-analysis. Our second criterion for inclusion was that all studies have a measure of SVO (Van Lange et al. 1997).

We use the correlation as the standardized effect size. A positive correlation indicates that liberals are more concerned with others’ outcomes. We analyze the overall effect size using a random effects approach. This is because we do not assume that we have collected the entire population of studies that have examined the relation between political orientation and SVO and that there may be both systematic and random variation in the effect size distribution (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). We conducted this analysis by using comprehensive meta-analysis software.

Results

The overall analysis is based on five studies (n = 3,068) conducted in three different countries. Table 3 displays each study and the corresponding coded effect size. As displayed in Table 3, each study found a small positive correlation between political ideology and SVO, ranging from .09 to .22. Indeed, the random effects analysis revealed a statistically significant positive relation between political ideology and SVO, r = .15, 95% CI [.09, .20]. As displayed in Table 3, across these studies individuals with liberal ideologies display greater concern for others’ outcomes, compared to individuals with conservative ideologies.

Table 3.

Meta-analysis Examining the Relation between Political Ideology and Social Value Orientation.

| Study name | N | Country | r | LL | UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balliet et al. (current study) | 728 | US | .13 | .06 | .20 |

| Sheldon and Nichols (2009) study 4 | 135 | US | .19 | .00 | .36 |

| Van Lange et al. (2012) study 1 | 238 | IT | .19 | .06 | .31 |

| Van Lange et al. (2012) study 2 | 497 | IT | .22 | .06 | .30 |

| Van Lange et al. (2012) study 3 | 1,470 | NL | .09 | .04 | .14 |

| Overall effect size | 3,068 | .15 | .09 | .20 |

Note: A positive correlation indicates that left-wing (vs. right-wing) ideologies relate to more concern for others’ outcomes. US = United States; IT = Italy; NL = Netherlands; LL/UL = lower limit/upper limit of a 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

A prevailing perspective in the contemporary research on the psychology of ideology is that individuals with liberal ideologies care more about equality, while individuals with conservative ideologies accept hierarchies and inequalities between individuals and groups (Carney et al. 2008; Thorisdottir et al. 2007), and that these ideological differences may result in conservatives being less willing to cooperate and more willing to take advantage of others. Consistent with this perspective, conservatives tend to support policies that promote self-interest, whereas liberals support policies that invest in collective outcomes and/or equality in outcomes, such as social welfare programs and addressing unemployment issues (Bastedo and Lodge 1980; Feldman and Zaller 1992). Moreover, conservatives (in Germany) self-report less concern and kindness toward others (Zettler and Hilbig 2010; Zettler, Hilbig, and Haubrich 2011).

These studies have often focused on countries outside the United States and used self-report of preferences or behaviors. The US political party system may be especially interesting to consider in research on conflict and cooperation, because it is dominated by two coalitions. Surprisingly, little research to date has examined how political ideology and members of different US political parties are more or less willing to cooperate both within and between political coalitions. Indeed, we are aware of only one study that has observed altruistic behavior between and within political coalitions: it found no difference between Democrats and Republicans in their display of altruistic behaviors (Fowler and Kam 2007)—although each party tended to show in-group favoritism. Here we extend this prior work by examining how US political ideology and political party affiliation predict (a) a general concern for others’ well-being, (b) a willingness to cooperate with others, (c) trust that others will cooperate, and (d) in-group favoritism in an interdependent cooperative decision making task. Table 4 provides a list of hypotheses and the support (or not) of these hypotheses in the present research.

Table 4.

Hypotheses Tested in Study 1 and Support (or not) for the Hypotheses.

| No. | Hypotheses | Support |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | People with liberal, compared to conservative, ideologies will show greater concern for others’ outcomes. | + |

| 2 | People with liberal, compared to conservative, ideologies will cooperate more in social dilemmas. | − |

| 3a | The relation between political ideology and concern for others’ outcomes is mediated by an egalitarian motive. | + |

| 3b | The relation between political ideology and cooperation is mediated by an egalitarian motive. | − |

| 4a | Conservatives, compared to liberals, will trust others less in social dilemmas (i.e., expected cooperation). | − |

| 4b | The relation between political ideology and cooperation is mediated by trust in others (i.e., expected cooperation). | − |

| 5a | Democrats are more cooperative with Democrats than with Republicans; and Republicans are more cooperative with Republicans than with Democrats (i.e., in-group favoritism). | + |

| 5b | People will show greater trust in in-group, than out-group, members. | + |

| 5c | Trust in in-group members will mediate in-group favoritism in cooperation. | + |

| 6 | People high in SDO will cooperate more with in-group, than out-group, members. | − |

| 7 | People high in RWA will cooperate more with in-group, than out-group, members. | − |

Note: SDO = social dominance orientation; RWA = right-wing authoritarianism.

+indicates rejecting the null hypothesis in support of the hypothesis.

− indicates failure to reject the null hypothesis and no support for this hypothesis.

We found that a unidimensional measure of political ideology (liberal vs. conservative) predicted a general concern for others’ outcomes, as measured by SVO. Specifically, liberals were more concerned about others’ outcomes than conservatives. As found in the meta-analysis, the positive correlation was consistently small in magnitude across five studies (see Van Lange et al. 2012). Besides generalizing these findings to a US sample, we were also able to find support for the theoretical perspective that this relation is the result of liberal, compared to conservative, ideologies’ relatively stronger concern for equality in outcomes. Specifically, concern for equality (as indexed by SDO) mediated the relation between political ideology and concern for others’ outcomes.

However, we did not find that liberals’ relatively greater concern for others’ outcomes translated into higher levels of cooperation across interaction partners. Instead, we found that both groups strongly favored individuals from their in-group compared to individuals from an out-group when deciding to cooperate. This in-group favoritism was also explained by greater amounts of expected partner cooperation from in-group members, compared to out-group members. Thus, although liberals were generally more concerned with equality in outcomes, this does not prevent them from discrimination in favor of their in-group, compared to the out-group, in terms of cooperation. Although this finding may contrast with the prevailing perspective that liberals, due to their egalitarian values, should discriminate less than conservatives, it is consistent with recent work that finds that both conservatives and liberals can discriminate against an out-group who is perceived to violate in-group values (Wetherell, Brandt, and Reyna 2013). Despite an emphasis on egalitarian values, liberals still discriminate in favor of in-group members. Such an observation fits with a general perspective that in-group favoritism in cooperation is a universal strategy to gain the indirect benefits of reciprocity from in-group members and reduce the possibility of exclusion from the group (Yamagishi, Jin, and Kiyonari 1999; see also Balliet, Wu, and De Dreu 2014; De Dreu, Balliet, and Halevy 2014). In support for this perspective, we found that people discriminated in favor of their in-group due to increased expectations of cooperation from in-group compared to out-group members.

SDO and RWA

Prior research suggests that SDO and RWA may lead to intergroup discrimination, but that this discrimination will occur for groups that are either considered competitors or a threat to a moral order (see Duckitt 2001; Duckitt and Sibley 2009, 2010). In the context of intergroup competition between political coalitions, it seems reasonable to assume that the out-group can be viewed as a competitor in the zero-sum game of political elections, and hence competitors in shaping the types of policies that are in those groups’ interests (e.g., as related to gay marriage, abortion, and gun policy). Yet, it is important to note that we did not observe an interaction between RWA (and SDO) and participants’ political party identification in predicting discrimination between Republicans and Democrats in cooperation. Instead, the data revealed a general pattern to discriminate, regardless of individual differences in ideological variables.

US Political Parties and Stereotypes about Cooperation

The present research also uncovered a novel finding that deserves brief comment. In particular, participants overall expected significantly more cooperation from Democrats than from Republicans. This finding is noteworthy for two reasons. First, it suggests that people tend to hold general beliefs about differences between Republicans and Democrats and that such beliefs may well guide expectations about specific behaviors. It is true that this main effect needs to be considered in light of the interaction with own political ideology: Republicans did not expect more cooperation from Democrats than from Republicans. Nevertheless, we observed an overall tendency to expect more cooperation from Democrats than from Republicans. Second, it is interesting that the overall tendency to expect more cooperation from Democrats did not translate into a tendency to extend greater cooperation toward Democrats. Future research is required to uncover the meaning of and explanation for this pattern. Future research could also illuminate general beliefs that people hold about Democrats and Republicans and explore how these beliefs might underlie cooperative behavior.

Limitations

The present study had a few limitations. First, it is possible that the manipulation of partner group membership attenuated variation in cooperation that could be uniquely explained by political ideology. Follow-up research would benefit from also observing cooperation with an unclassified stranger—perhaps differences in ideology are most pronounced in contexts in which coalitional membership is not salient. Second, we measured our mediating variables (SVO, SDO, and RWA) after participants made their cooperation decisions. Therefore, participant’s cooperation decisions could have influenced responses to the measure of SVO. However, this is unlikely because we replicate the exact same correlation found in a meta-analysis of eighty-two studies on the relation between SVO and cooperation (r = .30; Balliet, Parks, and Joireman 2009).

Third, we used a dyadic social dilemma task to study cooperative interactions between individuals that belong to different political coalitions. Such social dilemma tasks can be criticized for being abstract and lacking ecological validity. However, a strength of social dilemma tasks is that they have high internal validity in establishing a social interaction that contains a conflict of interests. This conflict of interests can characterize many forms of negotiations, group projects, and intergroup exchanges which politicians can face (see De Dreu 2010). Moreover, research has found that behavior in these social dilemma tasks do predict cooperation in real-world situations that involve a conflict of interests (see Van Lange et al. 2014).

Lastly, the methods involved hypothetical decisions and each participant interacted with both in-group members and out-group members. Prior researchers have suggested that people may positively discriminate in favor of their in-group when discrimination is relatively costless (Yamagishi, Jin, and Kiyonari 1999). Moreover, it could be that discrimination in cooperation was the result of merely a contrast effect with the use of a within-subject experimental design. However, a recent meta-analysis on intergroup discrimination in cooperation finds that the amount of discrimination between in-group and out-group members is unaffected by participation payment (or not) or between-subjects (vs. within-subject) experimental designs (Balliet, Wu, and De Dreu 2014). Thus, we believe our findings are not an artifact of these features of the experimental design.

Concluding Remarks

Trust and cooperation are essential to a healthy, vibrant, well-functioning democracy. We find that cooperation and trust are strongly attenuated when people interact with another person from a rival political party. Even though we find some evidence that people with liberal, compared to conservative, ideologies tend to display greater concern for others’ outcomes and equality in outcomes, both liberals and conservatives tended to cooperate more with in-group, compared to out-group, members. This evidence is consistent with the position that in-group favoritism is a human universal that overrides the impact of political ideology on social behavior. Thus, both liberals and conservatives fall prey to the same discriminatory tendency to favor the in-group. Moreover, we obtained evidence supporting the mediation role of expected partner cooperation in accounting for this in-group favoritism in cooperation. Both Democrats and Republicans expected greater cooperation from in-group than out-group members, and this is what accounted for their tendency to cooperate more with in-group members.

Our findings suggest that political party affiliation may undermine cooperation with others, such as among neighbors, employees, and community members. And importantly, this may undermine the all-too-often lack of cooperation that occurs among elected government officials. Indeed, a well-functioning democratic government requires trust and cooperation to reach agreements and advance policy. A fruitful next step would be to gain greater insight into how people respond to information about other people’s ideology and political affiliation, and ultimately, how one can overcome the undermining effect of such information on trust and cooperation. This is perhaps as much a societal challenge as it is a scientific challenge. After all, in-group favoritism is a pervasive feature of human psychology, and any institutional measures developed to encourage trust and cooperation among people with different ideologies and political coalitions must address this basic phenomenon.

Notes

We did not have a priori predictions about how cooperation and intergroup discrimination in cooperation would differ before or after the 2012 US presidential election. When we included time of survey in all of the statistical tests of our hypotheses, time of survey did not influence the conclusions we draw from the tests of our hypotheses. Time of survey only had a statistically significant effect in one model, so we decided to exclude time of survey from all the models reported in the article and to report the one statistically significant effect in a footnote (see Note 4).

The Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) Scale has been found to have two dimensions: opposition to equality and group-based dominance (Pula, McPherson, and Parks 2012). Both opposition to equality and group-based dominance had adequate internal reliability (α = .90 and .95, respectively) and the subscales had a strong positive correlation, r = .61, p < .001. We examined if the two dimensions of SDO differentially mediated the relation between political ideology and social value orientation (SVO). We found that while support for group-based dominance hierarchies did mediate the relation between political ideology and SVO (indirect effect = 45.19, 95% CI [24.34, 70.56]), opposition to equality did not significantly mediate this relation (indirect effect = 11.56, 95% CI [−18.86, 83.36]).

In an additional model predicting cooperation where we added time of survey (before or after the 2012 US national election) as a between-subjects factor and three additional individual differences measures—SVO, overall SDO, and overall right-wing authoritarianism (RWA). People showed a slight tendency to be less cooperative before (M = 44.98, SD = 27.70), than after (M = 50.37, SD = 25.68), the election, F(1, 573) = 4.25, p = .04, ηp 2 = .01. SVO significantly related to cooperation, F(1, 573) = 52.21, p < .001, ηp 2 = .08. Hence, people who display greater concern for others’ outcomes were more willing to cooperate. However, SDO and RWA did not relate to cooperation (ps > .1), and this model did not affect results testing our hypotheses.

We tested an additional model predicting expected cooperation that included time of survey and three individual difference variables (SVO, SDO, and RWA). Participants who care more about others’ outcomes, as measured by SVO, tended to expect more cooperation from others, F(1, 571) = 8.81, p = .003, ηp 2 = .02. However, own party affiliation, time of survey (before or after the election), RWA, and SDO did not relate to expected partner cooperation. Participants’ party affiliation interacted with time of survey in predicting expectations of cooperation, F(1, 571) = 4.31, p = .038, ηp 2 = .01. Further simple effect analysis revealed that before the election, Democrats (M = 39.59, SD = 20.61) expected less cooperation compared to Republicans (M = 49.30, SD = 24.44), F(1, 577) = 12.76, p < .001, ηp 2 = .02. However, after the election, there was no difference between Democrats (M = 43.67, SD = 19.97) and Republicans (M = 45.11, SD = 21.67) in expected partner cooperation, F(1, 577) = 0.32, p = .57, ηp 2 = .0005.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Altemeyer Bob. 1981. Right-wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer Bob. 1998. “The Other ‘Authoritarian Personality’” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by Zanna Mark, 47–92. San Diego, CA: Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Balliet Daniel, Li Norman P., Joireman Jeff. 2011. “Relating Trait Self-control and Forgiveness within Prosocials and Proselfs: Compensatory versus Synergistic Models.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101:1090–105. doi:10.1037/a0024967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balliet Daniel, Parks Craig, Joireman Jeff. 2009. “Social Value Orientation and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas: A Meta-analysis.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12:533–47. doi:10.1177/1368430209105040. [Google Scholar]

- Balliet Daniel, Lange Paul A. M. Van. 2013. “Trust, Conflict, and Cooperation: A Meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 139:1090–112. doi:10.1037/a0030939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balliet Daniel, Wu Junhui, De Dreu Carsten K. W. 2014. “In-group Favoritism in Cooperation: A Meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 140:1556–81. doi: 10.1037/a0037737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastedo Ralph W., Lodge Milton. 1980. “The Meaning of Party Labels.” Political Behavior 2 (3): 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin Arlin James. 2006. “The Relationship between Right-wing Authoritarianism and Attitudes towards Violence: Further Validation of the Attitudes towards Violence Scale.” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 34:923–26. doi:10.2224/sbp.2006.34.8.923. [Google Scholar]

- Blass Thomas. 1995. “Right-wing Authoritarianism and Role as Predictors of Attributions about Obedience to Authority.” Personality and Individual Differences 19:99–100. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00004-P. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbio N. 1996. Left and Right. Cambridge, UK: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Donald T. 1965. “Ethnocentric and Other Altruistic Motives” In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, edited by Daniel Levine, vol. 13, 283–311. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carney Dana R., Jost John T., Gosling Samuel D., Potter Jeff. 2008. “The Secret Lives of Liberals and Conservatives: Personality Profiles, Interaction Styles, and the Things They Leave Behind.” Political Psychology 29:807–40. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00668.x. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes Robyn M. 1980. “Social Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Psychology 31 (1): 169–93. [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W. 2010. “Social Conflict: The Emergence and Consequences of Struggle and Negotiation” In Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by Fiske Susan T., Gilbert Daniel T., Lindzey Gardner, 983–1023. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; doi:10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy002027. [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W., Balliet Daniel, Halevy Nir. 2014. “Parochial Cooperation in Humans: Forms and Functions of Self-sacrifice in Intergroup Conflict” In Advances in Motivational Science, edited by Elliot Andrew, 1–44. New York: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt John. 2001. “A Dual-process Cognitive-motivational Theory of Ideology and Prejudice” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol 33, edited by Zanna Mark, 41–113. San Diego, CA: Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt John, Fisher Kirstin. 2003. “The Impact of Social Threat on Worldview and Ideological Attitudes.” Political Psychology 24:199–222. doi:10.1111/0162-895x.00322. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt John, Parra Cristina. 2004. “Dimensions of Group Identification and Out-group Attitudes in Four Ethnic Groups in New Zealand.” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 26 (4): 237–47. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt John, Sibley Chris G. 2009. “A Dual-process Motivational Model of Ideology, Politics, and Prejudice.” Psychological Inquiry 20:98–109. doi:10.1080/10478400903028540. [Google Scholar]

- Duckitt John, Sibley Chris G. 2010. “Personality, Ideology, Prejudice, and Politics: A Dual-process Motivational Model.” Journal of Personality 78:1861–93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson R. S., Tedin K. L. 2003. American Public Opinion. 6th ed New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr Ernst, Schmidt Klaus M. 1999. “A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 114: 817–68. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman Stanley. 1988. “Structure and Consistency in Public Opinion: The Role of Core Beliefs and Values.” American Journal of Political Science 32:416–40. doi:10.2307/2111130. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman Stanley, Zaller John. 1992. “The Political Culture of Ambivalence: Ideological Responses to the Welfare State.” American Journal of Political Science 36:268–307. doi:10.2307/2111433. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler James H., Kam Cindy D. 2007. “Beyond the Self: Social Identity, Altruism, and Political Participation.” Journal of Politics 69 (3): 813–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jost John T., Federico Christopher M., Napier Jaime L. 2009. “Political Ideology: Its Structure, Functions, and Elective Affinities.” Annual Review of Psychology 60:307–37. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost John T., Thompson Erik P. 2000. “Group-based Dominance and Opposition to Equality as Independent Predictors of Self-esteem, Ethnocentrism, and Social Policy Attitudes among African Americans and European Americans.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 36 (3): 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey Mark W., Wilson David B. 2001. Practical Meta-analysis. London, UK: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto Felicia, Sidanius Jim, Stallworth Lisa M., Malle Bertram F. 1994. “Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67:741–63. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher Kristopher J., Hayes Andrew F. 2004. “SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models.” Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 36 (4): 717–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt Dean G., Kimmel Melvin J. 1977. “Twenty Years of Experimental Gaming: Critique, Synthesis, and Suggestions for the Future.” Annual Review of Psychology 28:363–92. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.28.020177.002051. [Google Scholar]

- Pula Kacy, McPherson Sterling, Parks Craig D. 2012. “Invariance of a Two-factor Model of Social Dominance Orientation across Gender.” Personality and Individual Differences 52 (3): 385–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon Kennon M., Nichols Charles P. 2009. “Comparing Democrats and Republicans on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Values.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 39:589–623. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00452.x. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif Muzafer. 1966. Common Predicament: Social Psychology of Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin comp. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius Jim, Pratto Felicia, Mitchell Michael. 1994. “In-group Identification, Social Dominance Orientation, and Differential Intergroup Social Allocation.” The Journal of Social Psychology 134:151–67. doi:10.1080/00224545.1994.9711378. [Google Scholar]

- Thorisdottir Hulda, Jost John T., Liviatan Ido, Shrout Patrick E. 2007. “Psychological Needs and Values Underlying Left-right Political Orientation: Cross-national Evidence from Eastern and Western Europe.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 71:175–203. doi:10.1093/poq/nfm008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange Paul A. M. 1999. “The Pursuit of Joint Outcomes and Equality in Outcomes: An Integrative Model of Social Value Orientation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77 (2): 337–49. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange Paul A. M., Balliet Daniel, Parks Craig, Vugt Mark Van. 2014. Social Dilemmas: Understanding the Psychology of Human Cooperation. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange Paul A. M., Bekkers René, Chirumbolo Antonio, Leone Luigi. 2012. “Are Conservatives Less Likely to Be Prosocial than Liberals? From Games to Ideology, Political Preferences and Voting.” European Journal of Personality 26:461–73. doi:10.1002/per. 845. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange Paul A. M., Bruin Ellen M. N. De, Otten Wilma, Joireman Jeffrey A. 1997. “Development of Prosocial, Individualistic, and Competitive Orientations: Theory and Preliminary Evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73:733–46. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange Paul A. M., Michael Kuhlman D. 1994. “Social Value Orientations and Impressions of Partner’s Honesty and Intelligence: A Test of the Might versus Morality Effect.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (1): 126–41. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lange Paul A. M., Schippers Michaéla, Balliet Daniel. 2011. “Who Volunteers in Psychology Experiments? An Empirical Review of Prosocial Motivation in Volunteering.” Personality and Individual Differences 51:279–84. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.038. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell Geoffrey A., Brandt Mark J., Reyna Christine. 2013. “Discrimination Across the Ideological Divide: The Role of Value Violations and Abstract Values in Discrimination by Liberals and Conservatives.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 4:658–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi Toshio, Jin Nobuhito, Kiyonari Toko. 1999. “Bounded Generalized Reciprocity: Ingroup Boasting and Ingroup Favoritism.” Advances in Group Processes 16:161–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zettler Ingo, Hilbig Benjamin E. 2010. “Attitudes of the Selfless: Explaining Political Orientation with Altruism.” Personality and Individual Differences 48:338–42. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- Zettler Ingo, Hilbig Benjamin E., Haubrich Julia. 2011. “Altruism at the Ballots: Predicting Political Attitudes and Behavior.” Journal of Research in Personality 45:130–33. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2010.11.010. [Google Scholar]