Abstract

The high prevalence of gender-based violence (GBV) in armed conflict has been documented in various national contexts, but less is known about the complex pathways that constitute the relation between the two. Employing a community-based collaborative approach, we constructed a community-informed socioecological conceptual model from a feminist perspective, detailing how armed conflict relates to GBV in a conflict-affected rural community in Northeastern Uganda. The research questions were as follows: (1) How does the community conceptualize GBV? and (2) How does armed conflict relate to GBV? Nine focus group discussions divided by gender, age, and profession and six key informant interviews were conducted. Participants’ ages ranged from 9 to 80 years (n =34 girls/women, n = 43 boys/men). Grounded theory was used in analysis. Participants conceptualized eight forms of and 22 interactive variables that contributed to GBV. Armed conflict affected physical violence/quarreling, sexual violence, early marriage, and land grabbing via a direct pathway and four indirect pathways initiated through looting of resources, militarization of the community, death of a parent(s) or husband, and sexual violence. The findings suggest that community, organizational, and policy-level interventions, which include attention to intersecting vulnerabilities for exposure to GBV in conflict-affected settings, should be prioritized. While tertiary psychological interventions with women and girls affected by GBV in these areas should not be eliminated, we suggest that policy makers and members of community and organizational efforts make systemic and structural changes. Online slides for instructors who want to use this article for teaching are available on PWQ’s website at http://journals.sagepub.com/page/pwq/suppl/index

Keywords: gender-based violence, armed conflict, socioecological model, community-based approach, Uganda

Gender-based violence (GBV), which disproportionately affects girls and women, has been called the greatest human rights challenge of our time (Kristof & WuDunn, 2009). In 1979, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, now widely considered an international bill of rights for women, prohibiting discrimination and promoting equal treatment of people regardless of gender. Fourteen years after the ratification of the Convention, the UN General Assembly approved the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, defining violence against women, used interchangeably with “GPV” as:

… any act of gender-based violence [perpetrated by the family, community, or State] that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

(United Nations [UN], 1993, p. 1)

Despite these policy and operationalization advances, almost one in three women globally will experience intimate or non-partner physical or sexual violence in her lifetime (World Health Organization, 2016). Violence against women occurs across intersecting demographics and in countries at all levels of development (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006). Although some variation between national contexts is evident, with countries such as Japan representing the lower range of prevalence (15%) and Ethiopia the higher (71%), most countries’ prevalence rates fall between 25% and 60% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006). Actual rates are likely higher in consideration of the underreporting of GBV due to stigmatization and intimidation (UN, 2015b).

While GBV poses a significant challenge for communities everywhere, variation in prevalence suggests that sociopolitical conditions influence its occurrence, a relation feminist writers have documented in their emphasis on political or national level indicators (e.g., Else-Quest & Grabe, 2012) and legal rights, such as land ownership (Grabe, Grose, & Dutt, 2015). Armed conflict is another relevant sociopolitical condition, during which GBV escalates (Benagiano, Carrara, & Filippi, 2010), and 1 in 113 people are displaced globally (UN Refugee Agency, 2016). In spite of the challenges of collecting robust data on GBV in armed conflict settings (Hynes, Ward, Robertson, & Crouse, 2004), researchers have established the high prevalence of GBV in armed conflict through studies conducted in a number of countries. In Cote d’Ivoire, for instance, 57.1% women reported experiencing physical or sexual violence after age 15 and 20.9% of women reported experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) following armed conflict (Hossain et al., 2014). In Sierra Leone, 9% of women reported experiencing sexual assault during conflict (Amowitz et al., 2002). Researchers have illuminated the high prevalence of GBV in armed conflict in East Timor (Hynes et al., 2004), Ethiopia (Wirtz et al., 2013), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; Peterman, Palermo, & Bredenkamp, 2011). The latter has been characterized by human rights groups (e.g., Human Rights Watch, 2010) and the media as “the worst place on earth to be a woman” (PBS Newshour, 2012, p. 1) because of sexual violence atrocities perpetrated by rebels and soldiers. Among internally displaced women in Uganda, over 50% reported experiencing some form of IPV (Stark et al., 2010).

Sexual violence (Benagiano et al., 2010) and IPV (Hossain et al., 2014; Saile, Neuner, Ertl, & Catani, 2013; Vinck & Pham, 2013) are particularly evident during and following armed conflict. In fact, sexual violence during armed conflict has such a longstanding historical presence that its occurrence has been framed as a troubling, but inevitable, outcome of armed conflict (UN, 1998). Discourse and policy have begun to shift, however, to contest sexual violence as an inevitable outcome of armed conflict and enact accountability measures accordingly. For instance, because sexual violence is often utilized as a deliberate strategy in conflict, it now qualifies as a war crime, most recently highlighted in the conflicts in Rwanda and former Republic of Yugoslavia. In the Rwandan genocide alone, estimates indicate that men sexually assaulted anywhere from 100,000 to 250,000 women within a 3-month span (UN, 2015a).

The sequelae of experiencing the intersection of GBV in armed conflict include mental (Gupta et al., 2014), physical (Campbell, 2002), and social problems (Kelly, Betancourt, Mukwege, Lipton, & Vanrooyen, 2011) for affected individuals across the life span. Experiencing GBV, particularly in armed conflict, has been linked to posttraumatic stress (Gupta et al., 2014), intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, recurrent nightmares, difficulty concentrating, irritability, outbursts of anger (Liebling & Kiziri-Mayengo, 2002), physical pain, feelings of helplessness, suicidal thoughts, and feeling humiliated (Emusu et al., 2009). Moreover, GBV experienced during armed conflict and/or at the hands of intimate partners can induce acute and chronic health problems, including sexually transmitted infections, AIDS/HIV, seizures, convulsions, vaginal infections and bleeding, pelvic pain, backaches, and gastrointestinal problems (Campbell, 2002; World Health Organization, 2013). Social repercussions, such as limited educational and employment opportunities, coupled with stigmatization, constitute additional armed conflict and GBV sequelae. For instance, in the DRC, 29% of raped women’s families viewed the women as contaminated and subsequently rejected them (Kelly et al., 2011). Notably, a mother’s mental health status has a predictive relation to her children’s mental health status (Robertson et al., 2006), reflecting a familial effect.

Children as young as 18 months in any context (Kerker et al., 2015) who have experienced adverse childhood events, such as abuse, neglect, witnessing IPV, and violence associated with armed conflict, manifest developmentally congruent mental and physical outcomes. Demographic and Health Survey data from 29 low- and middle-income countries indicated that witnessing maternal physical or sexual IPV had detrimental effects on children’s growth trajectories and overall physical health (Chai et al., 2016). Ugandan children who were internally displaced because of armed conflict described experiencing several culturally bound categorizations of mental distress: two tam, kumu, par, kwo maraco, ma iwor, and kwo maraca, involving symptoms of crying easily, low self-worth, worry, insomnia, pain in the heart, headaches, stomachaches, and oppositional and antisocial behavior (Betancourt, Speelman, Onyango, & Bolton, 2009; Verdeli et al., 2008). Adolescents who have experienced adverse childhood events in conflict settings are susceptible to high risk drug use and sexual behavior, leading to elevated risk for developing sexually transmitted infections and HIV (UN Population Fund, 2002) as well as becoming perpetrators as they age. For instance, boys in Sri Lanka who experienced adverse childhood events, including experiencing abuse or witnessing IPV, demonstrated a higher risk for adult perpetration of IPV (Fonseka, Minnis, & Gomez, 2015). In adulthood, those who have experienced adverse childhood events in general exhibit increased parental stress (Steele et al., 2016). In sum, experiencing or witnessing GBV has deleterious effects on people across the life span and may be exacerbated in armed conflict.

Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding GBV in Armed Conflict

Feminist theorists assert that GBV in armed conflict is primarily based on, and perpetuated by, patriarchy and heterosexual masculine expectations amplified through militarization and expectations of aggression constructed for men, which are challenged, tested, and provoked by male leaders and peers in armed conflict settings (Banwell, 2012). Social constructivists highlight hegemonic masculinity as an organizing structure of power relations, attained through interactions reflecting authority and dominance of others (Leatherman, 2011). From a constructivist perspective, individuals enact diversified, fluctuating, and modifiable constructed masculinities (e.g., dominant and subordinate) as well as femininities (e.g., victim and combatant), both of which are influenced by cultural conditions, including the culture of armed conflict. The impermanent and flexible expression of gender, coupled with the vying for dominance in armed conflict settings, often encourage various forms of interpersonal violence, including GBV (Leatherman, 2011).

We employed a socioecological framework from a feminist perspective for the present study, as recent IPV researchers have called for the increased use of multifactorial approaches; a more sophisticated integration of intersecting individual, familial, and social factors (Banyard, 2011; Hamby, 2011); and the examination of multiple forms of violence concurrently (Grych & Swan, 2012). Employing a socioecological framework to examine GBV in armed conflict specifically addresses these recommendations. The World Health Organization (2015) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015) have adapted Bronfen-brenner’s (1977) ecological model of human development to conceptualize interpersonal violence. Their models include four levels: individual, relationship (microsystem), community (exosystem), and societal (macrosystem); the latter constitutes the conceptual sphere for a feminist emphasis on societal structures, such as patriarchy (Patton, 2015). We have heeded recommendations that when conceptualizing GBV, feminist attention to patriarchy and gender inequality be integrated with other structural, individual, family, and community variables that critics assert are sometimes downplayed or overlooked in feminist writings (Keating, 2015).

Heise (1998) was one of the first to apply a socioecological framework to violence against women, identifying variables related to the perpetrators and victims of violence against women across all four tiers of the model. More recently, investigators have implemented the socioecological framework to understand GBV, some with populations particularly relevant to the present study. For example, Keygnaert, Vettenburg, and Temmerman (2012) applied the model to refugee women from a variety of countries who experienced sexual violence and GBV in the Netherlands and Belgium. Hatcher et al. (2013) provided a socioecological analysis of GBV among pregnant women in rural Kenya. Laisser, Nystrom, Lugina, and Emmelin (2011) used a similar strategy in their study of IPV in semi-rural Tanzania. Findings have revealed internalized blame or shame on the part of women and alcohol consumption on the part of men at the individual level. At the relationship level, women’s isolation and lack of social support or transgression of gender roles, as well as men’s inability to provide resources and male unemployment or diminished control of resources in the relationship, were related to increased GBV (Laisser, Nystrom, Lugina, & Emmelin, 2011). At the community level, factors such as the lack of responsiveness or active perpetration by police, stigma, and community resistance to addressing GBV were consistent. Societally, inequitable laws and policies, poverty, and pervasive male dominance were central themes related to GBV (Heise & Kotsadam, 2015).

Rationale for the Present Study

Additional work to understand the complexities of GBV in armed conflict is warranted. Previous research using a socio-ecological framework, while informative, has not included armed conflict as a factor, in spite of its widespread occurrence and important relation of armed conflict with GBV, and no study of which we are aware has included voices from across the life span. Moreover, most research in Uganda has been conducted with internally-displaced persons in the Northern region who were displaced primarily because of Lord’s Resistance Army rebel activities (e.g., Akello, Reis, & Richters, 2010; Betancourt et al., 2009), ignoring other areas affected by armed conflict. Employing a feminist perspective, we aimed to fill these gaps by creating a data- and community-informed socioecological conceptual model of the relation between armed conflict and GBV in a conflict-affected, rural community in Northeastern Uganda. One of the aims of transnational feminist research is to increase relevance for local activists and partners (Adomako Ampofo, Beoku-Betts, & Osirim, 2008). Aware of our cultural positioning as outsiders and in agreement that the “global is local” (Marecek, 2012, p. 149), we first sought to provide a meaningful and relevant analysis and to establish a community-generated description of GBV with the following research question: How does the community conceptualize GBV? Second, we asked, how does armed conflict impact GBV? This second question was contextualized by our understanding that women and patriarchy are not monolithic entities across the globe (Mohanty, 1988) and that the relation between these two widespread forms of interpersonal violence—armed conflict and GBV—would reflect the particularities manifested in a community that has been marginalized both globally and locally.

Method

Study Site

The current study examined the intersection of armed conflict and GBV in a rural, conflict-affected community located in Katakwi District of the Teso subregion of Northeastern Uganda. Teso has been affected by armed conflict inflicted most recently by the Karamojong through cattle-rustling raids (armed attacks that include the looting of livestock), which have perpetuated instability in the area. The Karamojong are a nomadic, pastoralist ethnic group who have been conducting cattle raids among their subtribes for decades. However, when the Tanzanian army ousted Idi Amin in 1979, the Karamojong acquired thousands of AK-47s that Amin’s soldiers left behind when fleeing. Wielding the newly acquired weapons, the violent cattle raids spilled over into Teso (Jabs, 2007). The region has also suffered from the Uganda People’s Army’s rebel activities and the Lord’s Resistance Army’s attacks and abductions (Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Uganda, African Network for the Prevention and Protection Against Child Abuse and Neglect, & Dan ChurchAid, 2011). The Ugandan government began a disarmament program in Karamoja in 2006, which has somewhat reduced the cattle raids. However, sporadic cattle rustling activities still occur and several communities, including the one under study, remain increasingly militarized with government (Uganda People’s Defense Force) soldiers and a special task force in the police sector called the Anti-Stock Theft Unit to protect kraals (corrals) against Karamojong cattle rustling. There is a dearth of literature about the GBV related to these raids, which contrasts with our local partners’ anecdotal observations and reporting that GBV is a serious, conflict-related community problem in this area.

Procedure

We employed a community-based collaborative approach, informed by the tenets of participatory approaches (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008), a common method selected to reduce health (including mental health) disparities across racial, ethnic, and class divisions, which consists of co-learning and attending to power imbalances, building local community capacity and participation, and balancing research and action (Fine, 2013; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008). Consistent with feminist theory, we designed our study to share power with our community-based research partners and benefit the communities involved through action and information dissemination (Israel et al., 2008). We also infused our feminist perspective throughout the project by honoring our participants’ voices through our qualitative methodology, attending to emergent patriarchal themes in coding and analysis as it was evidenced locally, attending to our positionality as researchers, and using knowledge engendered to enact change (Patton, 2015).

We collaborated with two local Ugandan-staffed groups: a non-governmental organization (NGO) and a community volunteer group. Prior to this research endeavor, the local NGO had been implementing programming that specifically targeted the prevention of, and response to, GBV in Katakwi District. Due to the applied nature of the NGO’s programming, the directors requested that the research approach be community-based and have an action and information dissemination component incorporated into the study design. The NGO had anecdotal evidence regarding the high rates of GBV in the surrounding communities experiencing armed conflict and denoted that more formal data collection and analyses would be valuable for an improved understanding of the complexities fueling the problem, in order to guide programmatic efforts. Through the NGO’s community-based activities, their staff had previously partnered with, supported, and trained a community volunteer group, consisting of approximately 15 male and female members who had spontaneously organized several years prior to address the high rates of GBV in their community, which the group had observed as escalating in conjunction with the heightened presence of military and police personnel. Together, the first author, the local NGO staff, and members of the community group constructed the study design by determining sampling frames and focus discussion groupings in order to be representative of the community, developing question guides that addressed all partners’ interests, and facilitating the project in order to meet shared goals.

Patton (2015) suggested that qualitative methods are preferable for international work because of the paradigmatic attention to social sensitivity, respect for differences, and desire to understand the participants’ perspectives. The excavation of narratives also is congruent with feminist principles (Patton, 2015). To better understand social experiences and collect data in a social context, we employed focus group discussions and individual interviews with key informants. Focus groups are a culturally sensitive method for groups that value collectivity (Kieffer et al., 2005) through which participants have the opportunity to share perspectives in their native language; the approach is consistent with community-based tenets (Montoya & Kent, 2011; Patton, 2015).

To enhance the quality and credibility of our investigation, we interviewed and conducted focus groups with a variety of sources, constituting source triangulation (Patton, 2015). In consideration of GBV and armed conflict’s widespread and pervasive effects on all those involved, we deliberately included participants across the life span to capture their unique perspectives and experiences (Kieffer et al., 2005). In addition to nine focus groups conducted with participants divided by gender, age, and profession, which were organized based on local social norms related to developmental stages (e.g., over age 55 constitutes an elder) and gender relations (i.e., all groups were gender-segregated with the exception of elders), we conducted semi-structured individual interviews with six key informants identified by our local partners based on their professional work with the community in various capacities related to GBV and armed conflict (Kieffer et al., 2005; Patton, 2015).

Participants

The sample consisted of 77 participants, selected purposively from our partnering agencies to be representative of the diversity of the community (e.g., varied neighborhoods and ethnicities), ranging from 9 to 80 years of age (M = 30.04, SD = 20.13), including 18 girls, 16 boys, 16 women, and 27 men. Of note, Uganda has “the youngest population in the world” (Bwambale, 2012, p. 1) with nearly half of its population under age 15 and roughly 4% of the population age 55 and older (Central Intelligence Agency, 2016), a demographic distribution likely resulting from Ugandan women having the third highest birth rate globally in conjunction with an average Ugandan life span of approximately 50 years. Participants’ ethnicities were Iteso (90.9%), Acholi (5.2%), Langi (2.6%), and Bantu (1.3%). There exist numerous ethnic groups in Uganda with more than 50 languages spoken. The national ethnic breakdown in Uganda is Baganda (16.9%), Banyankole (9.5%), Basoga (8.4%), Bakiga (6.9%), Iteso (6.4%), Langi (6.1%), Acholi (4.7%), Bagisu (4.6%), Lugbara (4.2%), Bunyoro (2.7%), and other (29.6%; Central Intelligence Agency, 2016). The large percentage of Iteso people in this study is due to the geographic area where the study was conducted. Youth’s education levels ranged from primary grade one to primary grade seven (M = 4.5, SD = 1.80). A minority of youth (5.9%) lived with both parents; most (64.7%) lived with a single or widowed mother, whereas only 2.4% lived with their father only. The remaining youth lived with an extended family member, such as grandparent, aunt, or uncle. Adult education levels ranged from having no education to specialized training beyond a high school diploma (M = 7.59, SD = 4.78). The majority of adults (70.7%) were married, with approximately 17% identifying as single or widowed mothers and 12% identifying as single or widowed fathers. Over half of the adults identified as peasant farmers.

Interview Guides

Interview guides provided focus to the groups, while still allowing for flexibility (Kieffer et al., 2005), and they allow the researcher and community partners to determine beforehand the major discussion themes. In collaboration with our community partners, we developed an interview guide for use in the focus groups, utilizing open-ended questions (Krueger, 1998), such as “Which forms of gender-based violence are common in (name of community)?” “Why does gender-based violence happen?” and “How do the Karamajong raids impact gender-based violence, if at all?” to elicit responses representative of participants’ perspectives and focus discussion to address the research questions. We did not define GBV ahead of time to capture the community’s conceptualizations. The guides were implemented flexibly, making alterations as needed to incorporate new information gained from a previous focus group or to revise topic areas that were confusing to focus group participants (Krueger, 1998). Because of the focus group format and related risks associated with confidentiality, questions were designed to assess general perspectives rather than detailed personal experiences. For individual interviews, we used a similar guide with additional questions asking about each key informant’s role in responding to GBV and challenges they face in doing so. The guides were forward translated into Ateso by the GBV Programming Director and back-translated into English by the translator.

The Researchers

The first author (J.M.) shares the same skin color as early missionaries and colonizers of Uganda. She is a muzungu (widely-used term in Uganda for “White person”), middle-class woman from the United States, and had no prior connection to the community in this study, though she had long maintained interest in diverse African women’s issues through research and volunteer activities in the United States and Africa. She initiated a connection to the community through a partnership with the local NGO, a relationship developed between them because of their mutual concern about GBV in armed conflict situations. J.M. twice traveled to the study site. On the first occasion, she worked with local partners to co-create the study’s design and focus. On the second occasion, the local partners and first author collected data over a 2-week period. With qualitative, feminist, and community-based principles in mind, J.M. tried consistently to collaborate with cultural humility and ongoing reflection about her biases, power, and privileges as a researcher. She strove to remain open to feedback about herself and cultural presentation throughout the research process by including methodological tools to elicit observations from community partners. For instance, she observed that when introduced by the local NGO to the community volunteer group, the translator held his hand high up in the air to demonstrate J.M.’s education level, highlighting an area of power imbalance. Thus, in conversations and throughout the data collection process, J.M. emphasized that in spite of her education level, she lacked knowledge about the community’s experience and was enthusiastic about learning from them.

The second author is a White, middle-class, feminist researcher who teaches qualitative research methods in a counseling psychology doctoral program with an explicitly feminist-multicultural perspective. She has experience conducting community-based studies in collaboration with primarily urban, marginalized populations in the United States, including African American youth who have a parent/s with HIV/AIDS, immigrant women, and lesbian, bisexual, and transwomen. She has longstanding interests in international work, having lived abroad in Latin America as a child and being privileged to travel extensively in adulthood. Her primary role in this project was to provide methodological, scholarly, and writing support.

The third author is a White, middle-class, feminist researcher with both qualitative and gender- and multicultural-based scholarship interests and experience but without specialized focus in international issues, which comprises the focus of the article. Her primary role in this project was to provide input and guidance about the methodological and analytic considerations and help prepare, format, and edit the manuscript.

Data Collection

Focus group discussions

Following institutional review board approval, nine focus groups were conducted (see Table 1): younger girls (aged 9–12), older girls (aged 13–17), adult women (aged 18–55), three parallel focus groups with boys and men, a gender-combined elder group (over 55 years), an Anti-Stock Theft Unit group, and a group of police. We conducted focus groups in various confidential outdoor locations identified by our local partners as convenient, and the sessions transpired for approximately 30 (younger children) to 100 (adults) min (M = 60.30, SD = 24.70). Although English is the national language and the language used in education, many people in this rural region have had less access to formal education. Thus, the first author moderated the groups with the assistance of a male bilingual (Ateso and English) social worker from the partnering NGO who simultaneously translated. The social worker shared the same ethnicity (Iteso) as most participants and had a professional relationship with, but was not from, the community. Each focus group began with a translated written consent (adults) or assent (children) form. For children aged 9–17, parental consent was also obtained. The translator orally reviewed the written consent form with the participants to compensate for variations in reading ability. Throughout the discussion, the first author summarized and reflected emerging central themes back to the focus group and members were asked if they wanted to modify those points in any way, a crucial technique for obtaining participant feedback (Krueger, 1998) and strategy for providing an additional form of analyst triangulation (Patton, 2015). All group interviews were audio recorded and demographic information was collected at the conclusion of the groups. Participants were compensated with 3,000 shillings (approximately US$1.50), an amount determined by the NGO to be concordant with local income and not unduly coercive, and were provided with a referral to a local organization in the event that they experienced distress. The first author debriefed with the translator following each focus group, and they collaboratively completed a contact summary form, noting main themes, interpersonal processes, unexpected findings, newly introduced topics, and comparisons and contrasts between other group conversations. They discussed any differences in interpretation until reaching consensus about meaning. For instance, younger children discussed suicide, but adults did not. Debriefing processes addressed the meaning of this discrepancy: namely that suicide was highly stigmatized and a topic that adults “hid,” and children were more likely to talk openly about their observations. Although the first author requested feedback from the translator regarding her interactions, no feedback was provided; the lack of response may be indicative of a power hierarchy, a difference in (in)directness of communication patterns (Hofstede, 2001), or the translator may have had few observations in this domain.

Table 1.

Focus Group Discussion and Individual Interview Characteristics.

| Sample | n | Age Range | Age M (SD) | Education Years M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group discussions | 71 | 9–80 | 30.04 (20.13) | 6.32 |

| Younger girls | 8 | 9–12 | 10.25 (0.89) | 3.13 |

| Younger boys | 9 | 9–12 | 10.56 (1.01) | 3.00 |

| Teenaged girls | 10 | 13–15 | 14.50 (0.71) | 5.90 |

| Teenaged boys | 7 | 13–17 | 14.86 (1.46) | 6.00 |

| Adult women | 8 | 30–43 | 36.75 (5.18) | 4.50 |

| Adult men | 8 | 30–48 | 38.63 (5.71) | 9.75 |

| Elders | 9 | 55–80 | 70.67 (8.35) | 2.67 |

| Anti-Stock Theft Unit | 9 | 25–48 | 43.26 (8.90) | 10.44 |

| Police | 3 | 29–54 | 39.67 (12.90) | 11.33 |

| Individual interviews | 6 | 25–54 | 44.00 (13.24) | 6.53 |

Individual interviews

The individual interviews, conducted by the first author with a Child and Family Protection Unit police officer, Head Nurse and Nursing Assistant of a local clinic, Head Teacher of the primary school (only school in the community), Assistant Community Development Officer of the subcounty, and Local Council 1 Chairperson, began with securing written informed consent, were audiotaped, lasted 30–60 min (M = 40.29, SD = 11.43), were conducted at key informants’ offices, and were facilitated in English at the participants’ request. Participants were likewise given 3,000 shillings for their participation and interviews and were debriefed with the translator who attended each interview, following the previously described contact summary guideline.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was ongoing and commenced at the onset of the research phase (Krueger, 1998). The first author took detailed field notes on her experiences during data collection, reviewed the contact summary forms, and through the routine debriefings with the translator, revised the interview guides as needed. For instance, the translator and first author noted the importance of querying specifically to obtain information about how HIV affects GBV, since the focus group members were not routinely covering these topics in their discussions, and it was an area of interest for the local community volunteer group because of their experiences and observations. In addition, the translator and first author noted that participants spoke minimally about sexual violence and began to query specifically for sexual violence (e.g., “Does sexual violence exist in [name of community]?” and “What kind of sexual violence exists here?”). These amendments likely elevated the reported frequency of HIV and sexual violence as well as enhanced our ability to conceptually document the relation of HIV to armed conflict and GBV and variables associated with sexual violence. Other revisions included altering language (e.g., “impact” to “effect”) for understandability. The first author transcribed the audiotaped, English translations of the focus group discussions and the individual interviews (which were conducted in English) verbatim, which allows for a more rigorous analysis (Krueger, 1998). A research assistant transcribed the debriefings.

The first author coded the transcripts using the grounded theory method of data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) and used open coding to extract categories and subcategories of meaning units, remaining close to the transcribed data. To honor Krueger’s (1998) recommendation that researchers conduct between-group analyses to strengthen results and enhance triangulation (Patton, 2015), the first author applied grounded theory to code each transcript. She then transferred the coding into separate spreadsheets for each focus group and each interview. Next, she conducted within-group and between-group analyses by completing and creating data analysis forms (noting statement context, frequency, extensiveness, specificity, and omission), frequency tables, and conceptual diagrams. She wrote a brief explanation for each focus group and interview, detailing what surfaced throughout the discussions, including notes on convergence and divergence from other focus groups and interviews. To open code the data, she read the transcripts line by line, determining where a complete idea began and ended. The complete idea became a meaning unit and was assigned a code, researcher-generated tags that closely reflect interview content (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Ninety-one open codes were generated which were then examined for clusters of related meanings, comprising 16 axial codes. Axial codes formed the basis for broader themes (selective coding; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The list of codes was shared with the translator, who provided feedback on their thematic and cross-cultural validity as an ongoing source of analyst triangulation (Patton, 2015). Following guidelines for grounded theory analysis, we applied the socioecological model’s four layers (Bronfen-brenner, 1977; Heise, 1998): individual (I), relational (R), community (C), and societal (S) to conceptualize and code the contributing variables to GBV. Contributing variables were labeled “individual” (I) if they occurred within the individual and seemingly in isolation of others (e.g., psychological reaction); “relational” (R) if they reflected an interaction between people (e.g., the wife challenging the husband); “community” (C) if they included perpetrators or survivors outside of the household (e.g., Karamojong raids); and “societal” (S) if they indicated broader cultural attitudes (e.g., patriarchy), policy (e.g., property rights), or conditions (e.g., poverty). In instances in which contributing variables might not be discrete, the variables were coded according to the layer that seemingly held the strongest association to GBV. For example, infidelity was coded as relational, since the GBV seemed to be most closely related to the ruptured relationship or jealousy associated with infidelity.

Dissemination

Disseminating the findings and moving toward action are vital final steps in community-based collaborative work (Kieffer et al., 2005). Immediately following data collection, the first author summarized key findings and submitted a report to the NGO, so that the organization could utilize the findings to apply for additional GBV programmatic funding. Moreover, to bolster action efforts, we collaboratively incorporated the additional research question, “What community-informed prevention and/or intervention strategies for GBV might emerge from the data?” with accompanying interview prompts to elicit community members’ and key informants’ ideas about action strategies as well as document community strengths and challenges to enact prevention and response efforts. Although not the focus of the current article, these data were also analyzed, collated, and written up for our local partners’ use and further dissemination for the community and involved professionals.

Results

Overview of GBV in the Community

Forms of GBV and contributing factors to GBV emerged as interrelated components in the analysis. Participants initially referenced 13 forms of GBV. Of those, we retained eight forms, omitting five due to their infrequent and inconsistent identification among focus group members and key informants (mentioned twice or less). We found that forms of GBV mentioned twice or less had little accompanying descriptive information to support analysis (e.g., lacking discussion around perpetrators and victims, contributing variables, and characterization qualities). In coding forms, we strove to capture participants’ conceptualization (e.g., coding sex work as a form of sexual violence and quarreling as a form of GBV) to enhance attention to context. The retained eight forms of GBV, in order of frequency discussed, were physical violence (80), sexual violence (46), quarreling (25), economic violence (inclusive of abusing rights; 20), early marriage (15), land grabbing (9), poor family relations (6), and failure to disclose HIV status (3).

Participants discussed physical violence (beating, battering, hitting, kicking, boxing, fighting, cutting with a machete, and murder) much more frequently than other forms of GBV. Almost all examples of physical violence were domestic and depicted the husband battering the wife. A key informant said, and several focus group members echoed: “It is one of the most common things here.” In contrast, sexual violence (rape, marital rape, defilement, sex work, and abduction) was rarely described as domestic. Rather, it was framed as occurring between people in the broader community. There was disagreement among the key informants about how common an occurrence of sexual violence is in the community, with most characterizing it as infrequent and one key informant describing it as highly common. Table 2 details the eight forms of GBV and, where possible, documents associations between forms of violence, perpetrators, victims, contributing variables, and how the forms of violence were characterized (e.g., occurring in the home or in the community). Physical violence, sexual violence, quarreling, early marriage, and land grabbing were explicitly associated with the Karamojong raids.

Table 2.

Forms of GBV in a Conflict-Affected Community in Northeastern Uganda.

| Forms of GBV | Perpetrator Terms | Victim Terms | Contributing Variables | Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical violence (beating, battering, hitting, kicking, boxing, fighting, cutting with machete, murder) *80 | Husband, father, men, man, dad, he, brother, gentleman, dad and mom, people, somebody, me, they | Wives, woman, mother, girls, the poor, somebody, you, mother, she | Poverty (S), patriarchy (S), Karamojong raids (C), dowry system (C), resources stolen (C), wife denies husband (R), wife challenges husband (R), poor family relations (R), wife requests from husband (R), perpetrator blames victim (R), infidelity (R), HIV disclosure (R), alcohol use (I), positive HIV status (I), psychological reaction (I), unemployment (I) | Common, often paired with quarreling, in the home |

| Sexual violence (rape, marital rape, defilement, forced sex work, abduction by the Karamojong) *46 | Soldiers, Karamojong warriors, teachers, man, boys, father, male youth with a bad character, drug addicts, they, people/person, group of boys, police, woman, he | Women, girls, orphaned girls, the poor, children, girl children, children of the neighbors, you, young girls, them, widows, orphans, invisible people, psychiatric patients, young boy, my child, she | Poverty (S), power differential (S), Karamojong raids (C), dowry system (C), resources stolen (C), militarization (C), youth not supported (R), alcohol use (I), positive HIV status (I), widow status (I), death (I) | Uncommon, common, occurring in the community, occurring in the home when referencing intent to kill with HIV |

| Quarreling *25 | Someone, one, husband, a person, he, she, dad, people | Mother | Poverty (S), Karamojong raids (C), resources stolen (C), wife denies husband (R), wife challenges husband (R), poor family relations (R), perpetrator blames victim (R), HIV disclosure (R), alcohol use (I) | Bidirectional, often paired with physical violence, in the home |

| Economic violence (abuse of rights) *20 | Heads of households— fathers mostly, head of a family, man, dad, father, husband, both men and women | Widow, mother, children, woman, girl children, the other | Patriarchy (S), power differential (S), poor family relations (R), alcohol use (I) | In the home |

| Early marriage *15 | Soldiers | Girls, girl children, orphaned girls, she, me | Poverty (S), power differential (S), Karamojong raids (C), dowry system (C), resources stolen (C), youth not supported (R), death (I) | In the community |

| Land grabbing *9 | Husbands’ families, husband’s relatives, father’s brothers, young men, men, someone, he, they, you | Widowed women, elderly widowed women, single mothers, women | Patriarchy (S), no property rights (S), Karamojong raids (C), widow status (I), death (I) | Among extended families, in the community |

| Poor family relations *6 | Father, man | Wife, women, children | Patriarchy (S), positive HIV status (I) | In the home |

| Failure to disclose HIV status *3 | Man, men, he, husband | Partner, you, wife | No contributing variables offered | In the home |

Note. GBV = gender-based violence; (S) = societal variable; (C) = community variable; (R) = relational variable; (I) = individual variable.

Frequency mentioned.

Contributing variables are experiences, behaviors, interactions, or cultural conditions the participants described as causally related to the occurrence of GBV. Participants initially identified 40 variables contributing to GBV, either singularly (direct variables) or in conjunction with other variables to interactively contribute to GBV (paired variables). Of these, we retained 22 variables and, consistent with our prior established rule, omitted variables that informants collectively referenced twice or less (e.g., conception problems and personality as contributors to GBV). Table 3 elucidates explicitly identified interactions among contributing variables to GBV. Within each socioecological layer, variables are presented in order of frequency discussed.

Table 3.

Frequency and Type of Interactions Among Variables Contributing to Gender-Based Violence in a Conflict-Affected Community.

| Contributing Variables |

Individual | Alcohol Use |

Positive HIV Status |

Widow Status |

Death | Psychological Reaction |

Unemployment | Relational | W Denies H |

W Challenges H |

Poor Family Relations |

W Requests From H |

P Blames V |

Youth Not Supported |

Infidelity | HIV Disclosure |

Community | Karamojong Raids |

Dowry System |

Resources Stolen |

Militarization | Societal | Poverty | Patriarchy | Power Differential |

No Property Rights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol use *56 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||

| Positive HIV status *10 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Widow status *7 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Death *3 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Psychological reaction *3 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Unemployment *3 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Relational | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| W denies H *18 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| W challenges H *18 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||

| Poor family relations *16 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| W requests from H *12 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| P blames V *11 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Youth not supported *11 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Infidelity *6 | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HIV disclosure *6 | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Community | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Karamojong raids *23 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||

| Dowry system *6 | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resources stolen *4 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||

| Militarization *3 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Societal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poverty *27 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||||

| Patriarchy *20 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | |||||||||||

| Power differential *6 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| No property rights *3 | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Note. W = wife; H = husband; P = perpetrator; V = victim;

■ indicates interaction between variables;

denotes frequency mentioned.

Of note, alcohol use (I), both as a direct and paired contributing variable to GBV, far surpassed the identification of other variables. It was the only variable from the 22 named as a contributing factor in every focus group discussion and key informant interview. A key informant observed, “There is fighting normally when the man is drunk; he comes and beats the woman.” A boy from the group aged 9–12 focus group explained, “If dad goes to drink, it tends to poison him.” The most consistent interaction occurred between alcohol consumption (I) and two relational (R) triggers: the wife denies and/or challenges her husband. The representative narrative demonstrating the interaction between alcohol consumption, with the wife denying her husband, commences with the husband drinking alcohol, returning home, requesting something (usually food or sex), and the wife denying his request. The wife challenging or disagreeing with her husband (e.g., early marriage of their daughter), questioning him about his behavior (e.g., asking where he has been), or attempting to restrict his behavior (e.g., asking him not to drink alcohol or have extramarital affairs) also frequently interacted with alcohol use to contribute to GBV. A man offered his perception of women’s challenging: “If the mother says something to correct him, that is violence on him.”

The number and range of interactions among the varying levels of the socioecological framework are striking, reflecting the complexity of GBV in the context of armed conflict. Although proffering analysis for each socioecological interaction is beyond the purview of this article, we have aimed to provide sufficient detail for a contextual understanding of GBV in this conflict-affected community.

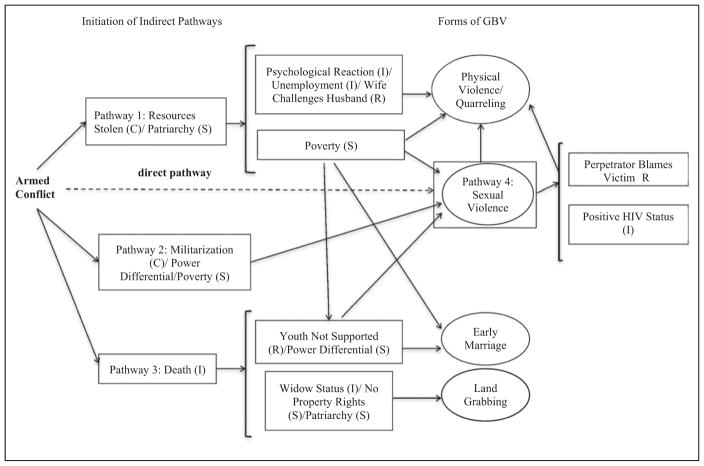

Direct Pathways Between GBV and Armed Conflict

The Karamojong raids (C) were directly connected to GBV in the form of sexual violence, especially rape and abduction (see Figure 1). Most examples depicted stranger rape between the Karamojong warriors and women and girls. A teenaged boy remarked, “The Karamajong warriors tend to come and they also end up raping these girl children in Teso.” A man reiterated, “Even the Karamajong go rape women.” The abduction of girls during the raids for the purpose of marriage and heavy domestic labor also emerged as a subtype of sexual violence. A woman shared the following:

The Karamajong also when they come—raiding hut or raiding cows—they come also and they abduct girl children. And when they take girl children to their place, they tend to turn them to become their housewives and also rape them or even subject them to a heavy kind of workload—to look after their cows from their area.

Figure 1.

Community-informed conceptual diagram of how armed conflict relates to gender-based violence in Northeastern Uganda. Note. (S) = societal variable; (C) = community variable; (R) = relational variable; (I) = individual variable;/= paired with; ▭ = contributing variable; ⬭ = form of GBV; GBV = gender-based violence.

Indirect Pathways Between GBV and Armed Conflict

More often than the direct link noted above, participants described armed conflict as distally connected to GBV via complex interactions with other contributing variables, including poverty (S), patriarchy (S), power differential (S), no property rights (S), resources stolen (C), militarization of the community (C), wife challenges husband (R), perpetrator blames victim (R), youth not supported (R), positive HIV status (I), widow status (I), death (I), psychological reaction (I), and unemployment (I; see Table 2 and Figure 1). The Karamojong raids initiated four discernable indirect pathways of events leading to GBV: (1) through stolen resources and patriarchy; (2) through militarization, power, and poverty; and (3) through death. A unique fourth track begins with sexual violence itself. A key informant stated, “It [Karamajong raids] contributes a lot [to GBV]. There’s killing, raping, looting of property.”

Looting of resources

Several participants spoke about the Karamojong stealing cattle or goats during their raids. For many families in the community, livestock is their primary source of livelihood and looting has profound consequences. Participants most frequently paired the Karamojong raids (C) with resources being stolen (C) and exacerbated poverty (S) as increasing the likelihood of quarreling and domestic physical violence occurring. A police officer explained how the raids increase poverty, offering a glimpse of the severity and extent of the poverty:

If the Karamajong come raiding, they take what you can use for plowing like the cows and oxens, and if the oxens are taken which are used for plowing, now famine will come in. And now, if there’s nothing that you can give to the family as support as something they can depend on to eat, you find now that there will be pollution between the husband and the wife.

Poverty (S), mentioned frequently, often was situated centrally between other contributing variables. The relation between poverty and the Karamojong raids is a good example of poverty’s broad influence. An elder, for example, discussed how poverty might be directly connected to both violence in the community and domestic violence. He stated:

The cause of this violence, one is poverty. When a person is poor, he thinks of so many things and it causes him to start violence in the community. Then also famine. If there’s nothing to eat in the home, there’s violence.

Another elder woman explained, “If you’re left without anything to eat in the family, then that man will approve a form of violence: psychological, physical.” Both examples specifically identify famine as the component of poverty that contributes directly to GBV. Quarreling was mentioned less frequently than physical violence, though quarreling contributed to GBV through poverty also (Pathway #1; Figure 1). A key informant explained:

Animals become property of some families, once they are raided, these are taken off—this one is poverty. Poverty causes violence in families, and mostly women are victim[s] because the man doesn’t provide for the necessities and then the woman is affected. He comes quarreling with the woman.

In addition, in the face of resources being stolen and limited, some women responded to increased poverty by engaging in sex work. A man noted:

If they [the Karamajong] come and uproot and destroy people’s crops, famine now comes in. And when famine comes in, you find that there’ll be nothing that’s provided as food in the home. And women will end up selling their bodies to those ones who have their monies.

We also heard patriarchal narratives (S), including content about men being the head of the household, men dominating the family and familial resources, and explanations about cultural customs (i.e., the dowry system and bride price), wherein women were conceptualized as property of men. Participants described men as the primary holders and executors of resources before their looting. Moreover, participants gave examples of men choosing to remain inside the home, not engaging with the Karamojong. In those instances, if the Karamojong stole the family’s resources (C), the participants spoke about wives challenging husbands (R) for failing to protect their resources and providing for their family. Regarding the Karamojong raids, discourse about wives challenging husbands extended to include challenging masculinity. Some men, then, responded to this relational exchange with physical violence. Making the connection among the raids (C), resources being stolen (C), increased poverty (S), and physical violence, a man observed how patriarchy (S), anger (I), unemployment (I), the loss of resources (C), and the wife challenging the husband (R) intersect:

You find that the animals are owned mostly by the families, and it’s always the heads of the families that own them. If I had a family and I had maybe ten animals, maybe the Karamajongs come and take them. I’ll be so angry. And when I’m so angry, each time something reminds, anything happens to me, as I stay at home, I stay at home with my wife. So when I’m angered, all my anger goes back to the woman, the children, that if it was not my animals are taking, I would not be the way [unemployed and without animals] you are talking that [about] right now. You find that women even say, “You can’t provide for me this or that. You are not a man.” And you find that it reminds me of what I had in possession and what was taken, so it brings violence, and it makes me to begin beating a woman.

Militarization of the community

The second pathway (Pathway #2; Figure 1) connecting the Karamojong raids (C) to sexual violence was initiated through militarization of the community (C). Police (e.g., the Anti-Stock Theft Unit) and soldiers are brought into the community ostensibly for protection from Karamojong raiders. However, the community recognized soldiers and police as perpetrators and both girl children and women as victims. One of our collaborating community partners’ members noted, “More police, more GBV.”

The soldier and police presence introduced a power differential (S) between service members and the community. In contrast with narratives of patriarchal beliefs and practices, narratives containing elements of a power differential exhibited greater emphasis on economic power and economic vulnerability, elucidating the entangled relation between poverty (S), economic power (S), and sexual violence especially. Table 2 shows that perpetrators of sexual violence include men who are in authority and earn a salary.

By contrast, victims were vulnerable children (e.g., low socioeconomic status and orphaned) and disadvantaged women (e.g., widowed or with a mental illness), all of whom one key informant astutely characterized as “invisible people.” Another key informant shared, “They [poor women] don’t have money. They don’t have what [money] and end up becoming victims of violence.” This power differential emerged frequently when referring to sex work as a form of violence. The following police officer’s statement is a cogent example of a narrative depicting a power differential (S) as well as poverty (S) and youth not being supported (R), themes related to sex work:

Because children are vulnerable. They need money. They need to buy their necessities and their parents cannot provide, especially girl children. They need [to buy] sanitary pads, they need books, they need pants, but they cannot provide. So they now go to those ones who have their economic stand. They have money and they are lured into sexual intercourse because of that small money.

Further demonstrating the pathway between militarization and sexual violence, a concerned teenaged girl noticed:

We have these military schools here and the police have their own school now. Because they have some salary, they use that very money for seducing girls and they give some small money to girls in exchange for sex. So, there’s a lot of sexual exploitation here because a girl is vulnerable.

Death of parent(s) or husband

In addition to having resources stolen (C; Pathway #1) and militarization of the community (C; Pathway #2), the impact of the Karamojong raids consists of a gendered component in that raiders tend to murder men and sexually or physically assault women and girls but leave them alive (Pathway #3; Figure 1). A woman explained, “They kill men and leave women. And if you accept to be raped, you are not killed.” Thus, death of a parent in this context usually referenced death of the father.

Having the father (or sometimes both parents) killed in armed conflict (I) lead to youth not being supported by the family (R), which paired with a power differential (S) to result in heightened risk for GBV. For girls, the vulnerability of being orphaned sometimes led to sex work or early marriage, even though marriage before 18 is now illegal by the Ugandan Penal Code Act (Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Uganda, 2010). A woman noted, “If the Karamajong come raiding, one, they come; they kill. And once they kill, they leave orphans. And those orphans are left vulnerable to violence within that community.” The teenaged girls’ focus group centered largely on early marriage, exhibiting their concern about a form of GBV that affects their particular demographic. For example, a teenaged girl observed the following:

If the Karamajong kill the father, she will now drop out of school and remain home for a short time and she will now start talking to the mother, “Let me get somebody who will now take care of me and who will take care of you, too.” That is now a thought of marrying that will support both the family and you as an individual.

The teenaged girls’ narratives demonstrated agency regarding utilizing early marriage as a form of survival. Most, for instance, referred to early marriage as a viable option, given their cultural context.

For wives, Karamojong raids which resulted in the death of their husbands (I) created widow status for such women (I) that paired with a lack of property rights (S) to lead to eviction from property by the husband’s family with consequent violence. Patriarchal themes (S) also permeated these narratives. Participants’ narratives suggested that women in this conflict-affected community have few, if any, rights to property and are often forcefully evicted from the property if their husband dies, a process colloquially known as land grabbing. A key informant expressed, for instance, “There is even a tendency of men denying women their rights—like inheritance of property at home.”

In every instance of land grabbing, women were widowed (I) and had no enforceable rights to their land (S) without their husband present. Husbands’ families strongly encouraged widowed women to marry one of the deceased husband’s relatives, usually a brother, or abandon the home and property. At times, the deceased husband’s family physically abused widowed women to drive them from the property. A key informant shared the following narrative that highlights how patriarchal values (S) influence land grabbing processes:

Definitely if the man is killed, sometimes there’s particular type of woman; you may find the relatives want to own the woman now. You know in our culture, some women are owned as property in the way that once she was married to that man lawfully. Or you have custom marry in my country. You find that when the man has been lost, they will expect that woman—the relatives will take over. So if there’s resistance from the woman—it can also cause violence. They all force her to stay with somebody of their choice. If she refuses, they will just chase her away.

Sexual violence

Descriptions of sexual violence as a form of GBV in armed conflict extended to indicate further complex cascades of GBV in the community and in the home (Pathway #4; Figure 1). For instance, the community observed that if a Karamojong warrior rapes a woman and her husband learns of her rape, he might blame her for the assault and perpetuate physical violence in the home. A woman shared:

And once you’re raped—and your husband now gets to know that you are raped—either in the bush or in the home—where you have hidden—and the man also starts now beating you up. He alleged that you are the one who accepted by the Karamajong, so he’s also beating you.

Other narratives revealed how girls and women performing sex work with soldiers or police (i.e., militarization) can disrupt family relations and lead to domestic physical violence. A key informant shared this, for example:

[There is] mostly the battering of women because also in fact it is almost at that rate because you find that there is a barracks there for soldiers. So as I told you the cause mostly is this poverty. You find that most women will have really gotten involved in a relationship with those soldiers there. And you know those soldiers have money and they can dish money anywhere. So women end up going with them, and you find that this disorganizes their families and that is the most common thing.

Another outcome arising from sexual violence included the contraction of HIV. A man highlighted how women or girls could contract HIV through rape: “Probably he’s (the Karamajong warrior) HIV positive and it [the rape] now results in HIV infection.” Women and girls could also contract HIV through sex work, another avenue contributing to increased domestic physical violence. Another man expressed, “There’s a lot of cross-generational and transactional sex and that will result into HIV/AIDS infection and now those families after discovering one is HIV positive now—there’s a lot of violence.” While participants did not explicitly discuss the perpetrator blaming the victim for contracting HIV related to the Karamojong raids, and thus this relation is not reflected in Figure 1, women did frequently pair these two variables when discussing domestic physical violence more broadly. One woman explained, for example, “The man just says, ‘Go and test. If you test positive, don’t come back here.’ If you come, and you tell him that, ‘I am positive,’ that is again a very harsh retaliation upon you. You are beaten.”

Discussion

To our knowledge, this community-based collaborative study with a rural, under-researched population in Northeastern Uganda is the first to construct a community-informed socioecological conceptual model that elucidates specific pathways and relations between complex mechanisms through which armed conflict affects GBV. We identified eight forms of GBV and 22 interactive contributing variables. Community participants most frequently discussed domestic physical abuse inflicted by husbands against their wives. The finding that domestic physical violence poses a significant challenge for women and girls in conflict-affected communities is consistent with other organizational conclusions (Amnesty International, 2007; Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Uganda et al., 2011) from qualitative work in Northern and Eastern parts of Uganda.

Participants noted that men commonly perpetrate domestic physical violence after consuming alcohol (an individual variable). This relation is well established by research conducted using various national samples (Abbey, Wegner, Pierce, & Jacques-Tiura, 2012; Thomson, Bah, Rubanzana, & Mutesa, 2015). Conditions associated with armed conflict could elevate the frequency and severity of alcohol use; some studies note the high prevalence of substance use with displaced persons, especially men (Ezard, 2012), due to trauma exposure and corresponding depressive and posttraumatic symptoms (Roberts et al., 2014; Weaver & Roberts, 2010). Participants in the current study identified connections among alcohol use, poverty and patriarchy, relational variables, unemployment, and being HIV positive. However, participants did not explicitly identify a connection between armed conflict and alcohol use, suggesting that in this community, if there is a perceived relation between the two, it is distal and likely mitigated by other factors. The evidence base for alcohol use by civilians living in conflict-affected communities remains scant (Ezard, 2012; Roberts et al., 2014). The evidence concerning alcohol use and GBV in armed conflict is even sparser, though initial studies (e.g., Ezard et al., 2011) have confirmed a connection between alcohol use and GBV with internally displaced persons. Because unemployment is high among internally displaced persons, men may feel that they have failed to meet their gender role expectation of provider and may drink alcohol to pass the time (Ezard et al., 2011). Roberts, Ocaka, Browne, Oyok, and Sondorp (2008) surveyed 1,206 internally displaced persons in Northern Uganda about their alcohol use and found that nearly one-third of men and 7.1% of women met the criteria for alcohol disorder. Being male, over the age of 50, and exposed to more than 12 traumatic events increased the likelihood of developing alcohol disorder 7 times more than women, 4 times more than those under 50, and 2 times more than those who had experienced fewer traumatic events, respectively.

The connections among contributing variables at all levels of the socioecological model demonstrated movement, fluidity, and perhaps most critically, interaction. For instance, in the context of domestic physical violence, alcohol consumption as an individual variable frequently was paired with relational triggers that involved resource acquisition or maintenance (e.g., wife denying or challenging the husband) as contributing variables. Other researchers have examined the relational variables of feeling upset with one’s partner, marital distance, forgiveness, social networks, decision-making, distribution of wealth, transgression of gender roles, and perceptions of infidelity (Hatcher et al., 2013; Heise, 1998; Katerndahl, Burge, Ferrer, Becho, & Wood, 2014; Key-gnaert, Vettenburg, & Temmerman, 2012). We surmise that several of these relational variables, such as decision-making, the distribution of wealth, transgression of gender roles, and perceptions of infidelity, correspond to resource acquisition and maintenance as motivating factors of GBV. For example, in many cultures, including the one under study, women themselves are widely perceived as commodities (Poulin, 2003). If the husband suspects infidelity, his claim to his wife as a resource is being threatened, and he inflicts violence to maintain her as a resource. Moreover, the relational exchanges were noticeably influenced by societal variables, such as patriarchy and its associated cultural customs, which organize gender roles and power relations in the household. Our results support other culturally informed research and theory that maintain that gender, power dynamics, and sexism are important contributing variables to GBV (Heise, 1998; Laisser et al., 2011), especially domestic physical violence. It is notable that individual, societal, and community processes routinely intersected with relationship triggers, variables, and couple interactions. Theoretical and statistical approaches should be complex enough to reflect these intersections. Recent studies conducted in the United States (Katerndahl et al., 2014; Miller-Graff & Graham-Bermann, 2014) and Africa (Thomson et al., 2015) have begun examining multidirectional influences on IPV, supporting the associations seen between indicators of poverty, alcohol use, relational dynamics, and GBV.

Armed Conflict and GBV

A benefit of conceptualizing GBV with community variables is that specific cultural variables can help to more fully explain the occurrence of GBV in a particular context. The community variable of the Karamojong raids demonstrated an entangled relation with physical violence/quarreling, sexual violence, early marriage, and land grabbing. Initiated through the armed conflict, we identified four events that perpetuate GBV in the home and community: the community variable of looting resources, the community variable of militarization, the individual variable of death of a person, and sexual violence.

Sexual violence stands apart from the other forms of GBV in that all pathways from armed conflict, direct and indirect, led to it, and the experience of sexual violence engendered further physical violence because of victim blame and the contraction of HIV. Despite its connection to all pathways, most community members and professionals described sexual violence as a rare occurrence. However, armed conflict directly instigated sexual violence in the forms of rape and abduction of girls and women, and considerable academic and media attention has been directed toward these forms of sexual violence in armed conflict (e.g., Leatherman, 2011), even if the experience of sexual violence is sometimes minimized in the context of war and death. Perhaps this attention, while likely still insufficient, is disproportionate considering the finding in this study and others that IPV often poses the largest threat to women and girls in conflict-affected communities in terms of GBV.

More often than a direct relation between armed conflict and sexual violence, an economic power differential frequently co-occurred with sexual violence as well as early marriage. For instance, death of a person, usually the male head of the household figure, triggered vulnerability for girls through loss of financial support, which subsequently paired with an economic power differential that led to sexual violence and early marriage. Militarization, too, instigated a power differential because soldiers and police receive financial remuneration, differentiating them from community residents who do agricultural work. Power differentials were understood as the intersection of economics with gender, with poverty especially affecting girls and women, an important exemplar of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991), a longstanding framework in African feminist writings (Beoku-Betts & Njambi, 2005; Lewis, 2001). Findings such as ours mimic others that show how girls and women are at risk for abuse from aid workers and other persons in power in conflict and emergency humanitarian settings (Ferris, 2007) and continue to be at risk for sexual assault from asylum professionals, such as police, lawyers, and security guards once relocated to host countries (Akhter & Kusakabe, 2014; Keygnaert et al., 2012).

Notably, the experience of sexual violence itself instigated further domestic physical violence through the relational variable of the perpetrator blaming the victim for the violence or through the individual variable of contracting HIV, which created subsequent discord in the family. The contraction of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections is a commonly cited direct (Kouyoumdjian et al., 2013) and indirect outcome of sexual violence due to increased risky sexual behavior, such as inconsistent condom use, for women with sexual violence histories (Stockman et al., 2013). HIV is less commonly studied as a risk factor for GBV, though some pioneering research examining the bidirectional relation between HIV contraction and IPV has begun. In a Kenyan study, for instance, women reported hiding HIV testing and status from partners because of fear of abusive reprisal (Hatcher et al., 2013). In a meta-analysis of 13 studies (12 from the United States and 1 from Haiti), women who experienced IPV were less likely to adhere to HIV treatment (Hatcher, Smout, Turan, Christofides, & Stockl, 2015). Despite recommendations from the World Health Organization (2004) regarding the dual training of medical personnel and integration of IPV and HIV services, enacting these recommendations has been slow to emerge with the exception of some recent work in Uganda detailing both the conceptualization of integrated services and testing integrated HIV and IPV intervention efficacy (Wagman et al., 2015). The contraction of HIV as a result of sexual violence, and the connection of sexual violence to a power differential, suggests that Rosenthal and Levy’s (2010) conceptualization of HIV risk in women from a Social Dominance Theory and the four bases of gendered power (force, resource control, social obligations, and consensual ideologies) framework could be conceptually useful in the designing of integrated HIV/IPV interventions. Women and girls with less power could present with restricted abilities to negotiate behavior change for themselves or their partners, which in turn could weaken integrated HIV/IPV interventions designed based on the assumption that women and girls be active change agents.

All of the societal variables of poverty, patriarchy, power differential, and lack of property rights connected with armed conflict and the various forms of GBV. Kazdin (2011) has argued that social problems related to interpersonal violence, including GBV, should be conceptualized as “wicked problems” (p. 171), which he characterized as complicated, involving numerous stakeholders and participants, resulting from intersecting trends, being embedded in other wicked problems, and eluding easy solutions. This study highlights the complexity of GBV and its embeddedness in other societal- and community-level wicked problems, including, but not limited to, armed conflict. Others have likewise referenced GBV’s complexity and its non-linear relations with other variables with which it is embedded (Katerndahl et al., 2014). We have found that the utilization of a socioecological framework from a feminist perspective in conjunction with a qualitative methodology acknowledges the complexity, embeddedness, and non-linearity of GBV in armed conflict. The finding that armed conflict is distally related to the various forms of GBV through numerous interactive contributing variables supports assertions that armed conflict does not characteristically induce GBV but, rather, exacerbates it (Torres, 2002). Community members’ articulation of their lived experience explicates the mechanisms through which the process of exacerbation occurs.

Practice Implications

The results hold numerous implications for practice. First, because of HIV’s connection to escalated domestic physical violence, the findings of this study indicate that increased energies directed toward encouraging men to test for HIV will be helpful (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010). Specifically, community awareness activities and attention to men’s cognitions about the contraction of HIV and partners’ roles in that contraction, as well as strengthening men’s coping skills and abilities to regulate emotion, will be productive areas of future research and in the designing of direct service clinical components. Moreover, the wicked problems (Kazdin, 2011) verified in the current study (e.g., armed conflict, poverty, and patriarchy) call for intervention efforts which aim beyond the individual in the elimination of GBV (Miller-Graff & Graham-Bermann, 2014). For example, (1) continued support of policy and governments that uphold peaceful negotiation and diplomacy over war and armed conflict, (2) advocacy and education to contest women’s and girls’ secondary status and unequal access to resources, (3) support for women’s and girls’ education and economic advancement to weaken economic power differentials, (4) legal protections for women’s ownership of land, and (5) widespread integration of IPV programming into NGO community development and emergency humanitarian responses that might prioritize assistance for those with intersectional vulnerabilities (e.g., orphaned girls) could help reduce GBV in armed conflict. In addition, host countries would be remiss to develop immigration restrictions based on economic standing, given women’s disadvantaged lack of access to resources in conflict settings. Finally, policy-level and organizational consideration from a gendered perspective for how those in power distribute money and other resources in conflict and humanitarian states is needed. These data serve as a reminder to continue to consider how to reconfigure gender roles within their cultural contexts: some of the constructed protectors of this community (e.g., soldiers and fathers/husbands) functioned also as aggressors.

Positionality Revisited