Abstract

Early histopathological studies of diabetic choroids demonstrated loss of choriocapillaris (CC), tortuous blood vessels, microaneurysms, drusenoid deposits on Bruchs membrane, and choroidal neovascularization. The preponderance of histopathological changes were at and beyond equator. Studies from my lab suggest that diabetic choroidopathy (DC) is an inflammatory disease in that leukocyte adhesion molecules are elevated in the choroidal vasculature and polymorphonuclear neutrophils are often associated with sites of vascular loss. There are subretinal and intrachoroidal neovascular formations in diabetic choroid at equator and in peripheral choroid. Modern imaging techniques demonstrate that blood flow is reduced in the subfoveal choroid. Angiography has shown areas of hypofluorescence and late filling that probably represent areas of vascular loss and/or compromise. Perhaps, as a result of vascular insufficiency, the choroid appears to thin in DC unless macular edema is present. EDI-SD OCT and SS OCT have documented the tortuosity and loss in intermediate and large blood vessels in Sattler’s and Haller’s layer seen previously with histological techniques. The risk factors for DC include diabetic retinopathy, degree of diabetic control, and the treatment regimen. In the future, angioOCT could be used to document loss of CC. Because most of the measurement and imaging are in the posterior pole, the severity of DC may be underappreciated in the published accounts of DC assessed with imaging techniques. However, it is now possible to document DC and quantify these changes clinically. This suggests that DC should be evaluated in future clinical trials of drugs targeting DR because vascular changes similar to those in DR are occurring in DC.

Keywords: Choriocapillaris, choroidopathy, diabetes mellitus, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, OCT

A. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) affects all small and large blood vessels in the body. Vascular dysfunction eventually results in tissue injury and degeneration. In the eye, the focus has always been the retinal changes that result in diabetic retinopathy (DR). However, it would seem logical that the choroidal vasculature would also be affected in DM and the choroid itself would degenerate resulting in diabetic choroidopathy.

The first report on diabetic choroidopathy, technically a diabetes-induced non-inflammatory degeneration of choroid, was from Hidayat and Fine (1985) in a small cohort of endstage, blind and painful diabetic eyes (Hidayat and Fine, 1985). In this cohort, there was choriocapillaris (CC) dropout, luminal narrowing, and thickening of basement membranes with arteriosclerotic changes in some arteries. Fryczkowski performed vascular casts of a small cohort of diabetic eyes and analysed the choroidal vasculature with scanning electron microscopy (SEM). (Fryczkowski, 1988; Fryczkowski et al., 1989). Loss of CC, large and intermediate blood vessel tortuousity, vascular hypercellularity and microaneurysms were documented with SEM in the human diabetic choroids.

B. Choroidal vascular loss

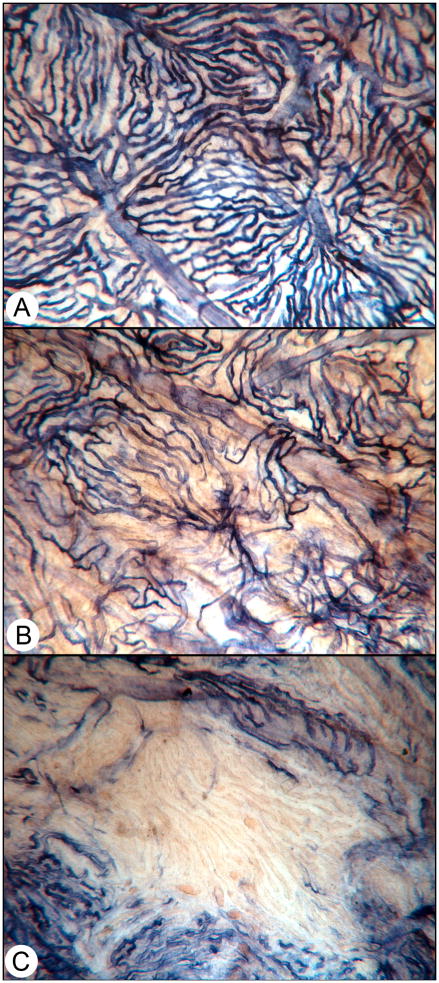

We documented the loss of functional CC in diabetic choroid using endogenous alkaline phosphatase (APase) enzyme histochemical activity. APase is present in the entire choroidal vasculature but it is more prominent in venules and veins than in arterioles and arteries; when enzyme activity is not present, there are no viable endothelial cells (Figure 1) (Lutty and McLeod, 2005; McLeod and Lutty, 1994). Furthermore, choroidal neovascularization (CNV) has the greatest enzyme activity (Figure 2). Large fields of CC were dysfunctional in flat mount preparations of diabetic choroids using this histochemical analysis and the subjects were not endstage but rather represented all stages and types of diabetics, many without retinopathy (Lutty and McLeod, 2005; McLeod and Lutty, 1994). The loss of functional choroidal blood vessels could be quantified using this method and image analysis. There were two types of loss: diffuse and complete. Diffuse loss had capillary segments missing but no defined areas of absolute CC loss, whereas complete loss had a defined border of atrophy with CC segments being APase− (Figure 1). The latter loss was able to be mapped and quantified and it was determined that there was four times more CC loss in diabetics than in older control, nondiabetic subjects (Cao et al., 1998). Probably this significant loss in viable vasculature resulted in hypoxic RPE and outer retina, for which the CC is the sole source of oxygen and nutrients.

Figure 1.

Alkaline phosphatase-incubated choroid from a diabetic choroid. (A) A normal area of choroid where all choriocapillaris are viable, i.e. are APase+. Organized lobules are apparent in this area. (B) An area in the same choroid that has diffuse choriocapillaris loss. (C) An area of complete loss of choriocapillaris. (With permission Figure 2 in Lutty, Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013; 54: ORSF81–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12979)

Figure 2.

Choroidal neovascularization in diabetic choroid. (A) Alkaline phosphatase incubated choroid from an 74 year old type 2 diabetic that has a large CNV formation (arrow). The yellow material is basal laminar deposit, which accumulates non-reduced formazan reaction product, thus the yellow color. The CNV formation is surrounded by areas with severe CC loss. (B) A section through the CNV that was stained with PAS and hematoxylin demonstrates a pink basal laminar deposit over the CNV (arrow) which has grown through a break in Bruchs membrane (Arrowhead).

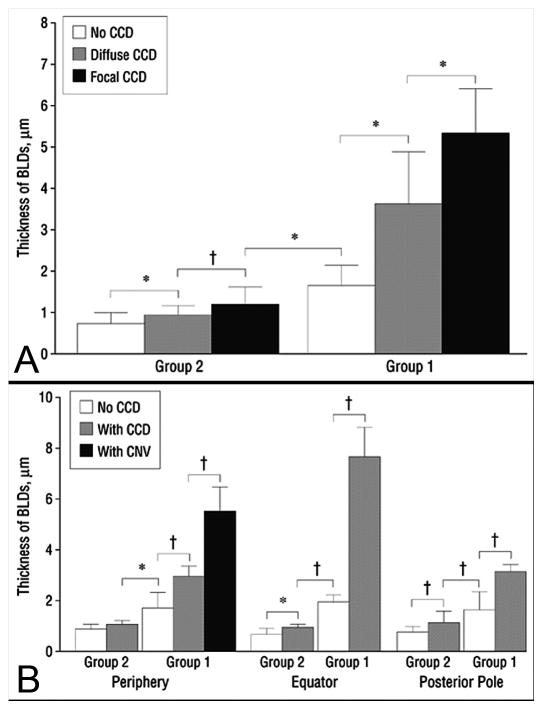

After the analysis of the vasculature in the flat perspective, the choroids were flat-embedded in glycol methacrylate, a transparent polymer from which two micron sections could be cut and then stained with traditional histochemical stains. Using PAS and hematoxylin staining, we observed accumulation of debris on Bruchs membrane (BrMb) that was similar to basal laminar deposits seen in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The height of these deposits was quantified and related to the complete choriocapillaris degeneration (CCD) and choroidal neovascularization (CNV) (Figure 3). The more severe the diabetic choroidopathy the greater the deposit height (Cao et al., 1998), suggesting that vascular insufficiency resulted in accumulation of debris on and in BrMb.

Figure 3.

Thickness of Bruchs membrane basal laminar-like deposits (BLD) in diabetic subjects. The thickness of Bruchs membrane deposits (+/−SD) was assessed in subjects with no choriocapillaris degeneration or dropout (CCD) (white), CCD (Gray), and CCD and/or CNV (black). (A) In group 2, nondiabetic aged control subjects with no measureable CCD, there was very little deposit. In group 1, the diabetic subjects had deposits that increased in thickness as areas with CCD became more severely affected, i.e. diffuse vs complete. (B) BLDs were significantly thicker in CCD areas in periphery, equator, and posterior pole and the thickest areas had CNV. Note only periphery had CNV.(asterisk = 0.05; dagger = , 0.01)

C. Etiology of choriocapillaris loss in diabetes

Diabetes is an inflammatory disease (Adamis, 2002). Elevated levels of TNFα and IL1β had been measured in diabetic sera compared to sera from control subjects, reinforcing DM as an inflammatory disease (Lampeter et al., 1992). Also, there are more activated leukocytes, especially polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), circulating in diabetics than in nondiabetics (Wierusz-Wysocki et al., 1987). It seemed logical that inflammation and inflammatory cells might contribute to loss of choroidal vasculature because Schmid-Schonbein had demonstrated accumulation of macrophages and PMNs in the retinas of diabetic rats (Schröder et al., 1991). In addition, the choroid is the site of many inflammatory pathologies like multifocal and serpighenous choroiditis, bird-shot choroidopathy, uveitis, central serous chorioretinopathy, and Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease.

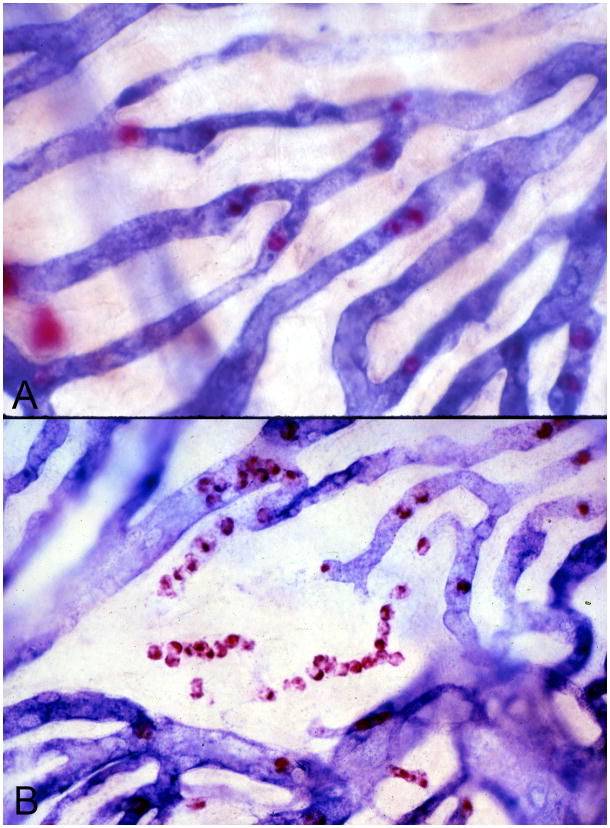

Our focus was PMNs because, once firmly adherent, they can undergo an oxidative burst that can damage endothelial cells (Springer, 1994). PMNs from diabetics exhibit a great oxidative burst than nondiabetic PMNs (Baranao et al., 1987; Freedman and Hatchell, 1992). Diabetic PMNs have a more rigid cytoplasmic membrane than nondiabetic PMNs making them more likely to be trapped in the microvasculature and cause capillary occlusion (Kelly et al., 1993). Human choroids were incubated for APase and nonspecific esterase (NSE; present in granulocytes and Mast cells) enzyme activity to evaluate PMNs and their association with CC loss (Cao et al., 1998; Lutty et al., 1997). PMN numbers were significantly increased in diabetic choroid compared to aged controls and they were often associated with areas of pathology like capillary loss and choroidal neovascularization (CNV) (Figure 4) (Lutty et al., 1997). There was a significant numerical correlation between CCD and the number of PMNs. There were often queues of PMNs in APase− CC and CNV that lacked APase activity. This suggested that PMNs contributed to vaso-occlusive events and endothelial cell injury in diabetic choroid.

Figure 4.

Alkaline phosphatase/nonspecific esterase (APase/NSE) double-labeled flat mounted choroids from nondiabetic subject (A) and an insulin-dependent diabetic subject (B). APase activity (blue reaction product) is localized to viable choroidal blood vessels while NSE activity (red reaction product) labels polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) within choriocapillaris lumens and mast cells, which are larger and out of focus since they found at the levels of Sattler’s and Haller’s layers. Queues of PMNs are present in degenerating segments of capillaries in the diabetic choroid (B). Note that PMNs are present within the choriocapillaris where APase activity ceases.

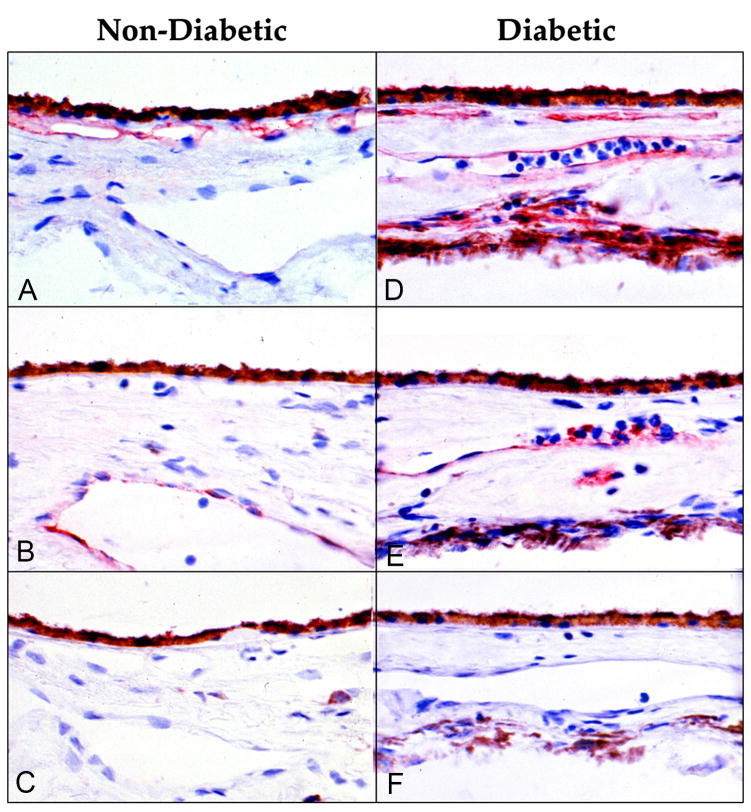

PMNs adhere to the endothelial cell lining of blood vessels after rolling along that surface. P-selectin initiates the rolling and firm adherence occurs when the endothelial cells express intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1); activated PMNs express CD11/CD18 on their surface, which binds to ICAM-1 (Springer, 1994). Both TNFα and IL1β are elevated in diabetic sera (Lampeter et al., 1992) and stimulate endothelial cell upregulation of adhesion molecules like P-selectin and ICAM-1. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that endothelial cells in CC constitutively expressed ICAM-1, making CC perhaps the only capillary system where this adhesion molecule is constitutively expressed (McLeod et al., 1995). In diabetic choroids, ICAM-1 was significantly increased throughout the choroidal vasculature (Figure 5) (McLeod et al., 1995). P-selectin was found in choroidal veins and venules of control subjects whereas it was observed in all choroidal vessels in diabetics. Upregulation of both adhesion molecules in diabetic choroid with elevated activated PMNs circulating in diabetics further supports PMN involvement in vaso-occlusive events in diabetic choroid.

Figure 5.

Immuohistochemical localization of ICAM-1 (A, D) and P-selectin (B, E) in a nondiabetic control subject (left) and insulin dependent diabetic subject (right). (A) ICAM-1 is constitutively made by normal choriocapillaris. (B) P-selectin is localized (red reaction product) only to large veins in control subjects. (C) There is no red reaction product when non-immune IgG is used as the primary antibody. (D) ICAM-1 is elevated in CC and present in all choroid blood vessels in the diabetic subject. (E) P-selectin is present in large and intermediate blood vessels in the diabetic subject. Bright red cells in lumens of blood vessels deep in choroid are platelets. (F) There is no red reaction product in sections of the diabetic incubated with non-immune IgG. The brown cells deep in choroid are melanocytes. (Red AEC reaction product and hematoxylin counter stain) (With permission, Figure 1 from McLeod et al. Am. J. Pathol. 1995; 147:642–653)

It is difficult, however, to demonstrate a causal relationship between PMNs and diabetic choroidopathy using postmortem human tissue. Fortunately, the studies of the Adamis lab demonstrate that the same scenario just proposed in human choroid occurs in diabetic rat retina. First, Lu and associates demonstrated that VEGF increases retinal vascular ICAM-1 expression (Lu et al., 1999). When they blocked ICAM-1 with neutralizing antibodies, leukostasis and vascular leakage were prevented (Miyamoto et al., 1999). Leukostsis was evaluated using the technique of Ogura where nucleated leukocytes are stained with intravenous acridine orange and an SLO was used to visualize them in the retinal and choroidal circulation (Ogura, 1999). When Barouch et al blocked CD18 they also prevented PMN adhesion and leukostasis (Barouch et al., 2000). If they made ICAM-1−/− or CD18−/− mice diabetic, they prevented leukostasis and endothelial cell death normally observed in diabetic retina (Joussen et al., 2004). Blocking TNFα with etanercept (a soluble TNFα receptor) inhibited leukostasis and endothelial cell injury in diabetes. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (high dose aspirin and a COX2 inhibitor, meoxicam) prevented early diabetic retinopathy via suppression of TNF-α (Joussen et al., 2002). Unfortunately, changes in choroidal leukostasis were not studied in these rodent experiments. They concluded from these studies that there is a central role for inflammation in DR (Joussen et al., 2004).

D. Intra and extrachoroidal neovascularization in diabetic choroidopathy

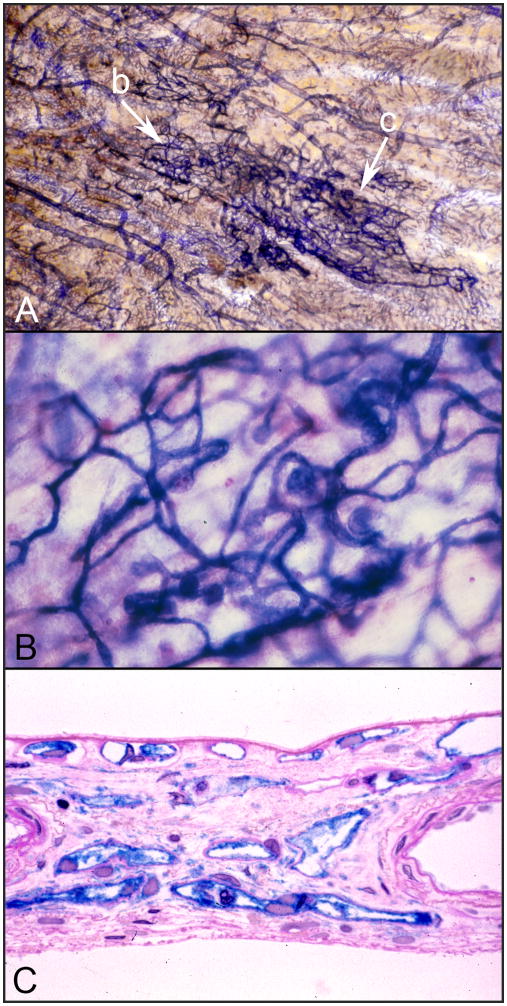

Loss of CC in diabetic choroid could make those areas of choroid and overlying RPE hypoxic. When RPE are hypoxic they upregulate VEGF production, which stimulates angiogenesis (Shima et al., 1995). In our studies of the diabetic choroid, we observed choroidal neovascularization (CNV) that was associated with areas of CC loss (Figure 2A) (McLeod and Lutty, 1994). The CNV was within and above BrMb and often appeared infarcted (tubes were APase−). In both studies that documented CNV in diabetic choroid, the CNV formations were at or peripheral to the equator (Cao et al., 1998; McLeod and Lutty, 1994). We have also observed intrachoroidal neovascularization which we termed intrachoroidal microangiopathy (ICMA) (Fukushima et al., 1997). ICMA are cobweb-like neovascular formations that are deep in choroid, often near lamina fusca, the boundary between choroid and sclera. They have very high APase activity, can be as large as 4.6 mm2 in diameter, and are connected to all levels of the choroidal vasculature (Figure 6). They were observed in 20% of the diabetic subjects studied but their position in choroid was not necessarily related to CC dropout areas. The only microaneurysms we documented in diabetic choroid were in ICMA formations (Fukushima et al., 1997).

Figure 6.

Intrachoroidal neovascularization or microvascular abnormality (ICMA) in the choroid of a 68 year old insulin dependent diabetic. (A) The ICAM formation is the dark blue cobweb like vasculature indicated with arrows. Note that the ICMA blood vessels have the most intense APase activity. (B) Higher magnification of the portion of the ICAM formation shown at arrow “b” in the APase flat mount shown in panel “A”. This area of the formation has bulbous microaneurysms. (C) A section through the dense portion of the ICMA formation indicated by arrow “c” in panel “A”. Notice that these ICMA capillaries are intensely blue and are located in outer choroid at the level of Haller’s layer where there are normally no capillaries. (section in (C) stained with PAS and hematoxylin in addition to APase reaction product.)

F. Clinical evaluation of human diabetic choroidopathy with new imaging modalities

ICG angiography allowed choroidal vascular sufficiency to be evaluated and was the first imaging modality to detect changes in the diabetic choroid. Weinberger and Gaton observed a “salt and pepper” pattern instead of ground glass with large hypofluorescent spots and large and small hyperfluorescent spots in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NDR), which correlated with poor diabetic control (Weinberger et al., 1998). Shiragami and Shiraga saw similar irregularities in diabetic subjects using ICG and fluorescein angiography and the hypofluorescent spots were significantly associated with DR, while hyperfluorescent spots were significantly associated with elevated HbA1c (Shiragami et al., 2002).

The advent of color Doppler imaging in the eye permitted blood flow to be assessed in diabetic eyes. The first study with this technique found that the central ophthalmic artery and vein had decreased flow in nonproliferative and background DR (Dimitrova et al., 2001). Subfoveal measurements demonstrated significantly reduced choroidal blood volume and blood flow in proliferative DR using laser Doppler flowmetry (Schocket et al., 2004). Another laser Doppler flowmetry study demonstrated a significant decrease in subfoveal choroidal blood flow in nonproliferative DR (NDR) (30%) compared with control and even more significantly in NDR with macular edema (ME) (48%) (Nagaoka et al., 2004). The limitation on these studies is that CC flow can only be assessed in subfovea where there is no retinal vascular interference in fovea. Therefore, we only have measurements in a very small area of choroid.

Recent imaging studies have focused on choroidal thickness, certainly a characteristic of diabetic choroidopathy or atrophy, but conclusions about changes in choroidal thickness in diabetics varies. Thinner diabetic choroids were found with increased microalbuminuria (Campos et al., 2016). A significantly thinner subfoveal choroid was found in all groups of type 2 Diabetic eyes compared to healthy eyes using 1060 nm OCT (Esmaeelpour et al., 2011). That study and another a year later found significant reduction in choroidal thickness in diabetic patients without retinopathy (Esmaeelpour et al., 2011; Querques et al., 2012). However, the change in thickness in diabetic macular edema (DME) is still controversial in that both thickening and thinning have been observed. One problem with these recent studies is that treatments were not considered. Both anti-VEGF and panretinal photocoagulation caused a decrease in choroidal thinning perhaps due to reduction in permeability of the choroidal vasculature (Melancia et al., 2016). An in depth discussion of these differences is reviewed by Melancia et al and Campos et al (Campos et al., 2016; Melancia et al., 2016). The consensus from these reviews is that choroid thins in diabetic eyes without DME and treatment of DME with anti-VEGF causes thinning of choroid. Malencia concluded that the majority of the studies suggest thinning of submacular choroid (Melancia et al., 2016). The one exception appears to be untreated DME in which choroid appears thicker in most studies.

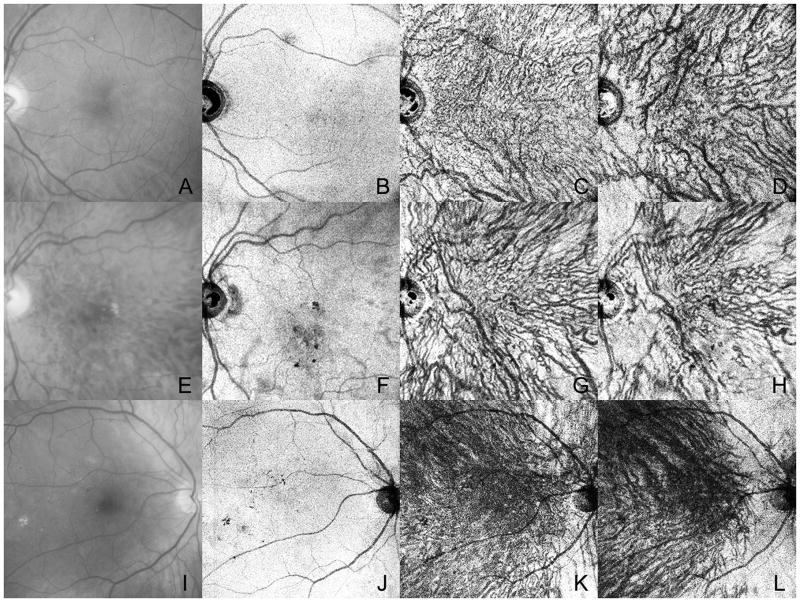

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has also contributed to our understanding of diabetic choroidopathy. Hua and associates used enhanced depth imaging spectral domain OCT (EDI-SD OCT) tomography and ICG angiography to study DC and observed hypofluorescent areas and late choroidal nonperfusion regions (Hua et al., 2013). These areas are potentially areas of choroidal nonperfusion or poor perfusion and, therefore, areas of choroidal hypoxia, which is a risk for DC with DR. Swept source (SS)-OCT has a longer wavelength, faster scanning speed, and invisible scanning light. This achieves better three-dimensional choroidal images and better evaluation of Sattler’s and Haller’s layer blood vessels. Ferrara et al used en face SS-OCT and observed choroidal vascular remodeling in all DM patients corresponding to irregular, tortuous and beaded choroidal vessels with focal dilatations and remodeling (Figure 7) (Ferrara et al., 2016). Enface SS-OCT at 1050 nm demonstrated loss of vessels in Sattler’s layer in 30% of the diabetic choroids and focal narrowing in vessels in Haller’s layer in 51% of the diabetic eyes, vascular stumps and aneurysmal changes in Haller’s layer (Murakami et al., 2016). Loss of vessels was related significantly to increased HbA1c.

Figure 7.

Imaging of three patients with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Red free images (A, E, I) of the subjects have very early changes like lipid and retinal hemorrhage. En face images from a swept source OCT is shown at different levels in the retina and choroid. (B–D) At the level of the RPE there are topographical changes due to loss of RPE (F) or shadowing from changes in sensory retina. At the level of inner choroid (C,G, K), the choriocapillaris is not clearly visible but irregular, tortuous, and beaded vessels can be seen. In outer choroid (D, H, L) enface images show attenuation of some large and intermediate vessels, especially in the subject shown in (H).(With permission, Figure 12 in Ferrara et al. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2016: 52:130–155)

F. Conclusions

Our first insights into DC were from the study of Hidayat and Fine in 1985 (Hidayat and Fine, 1985). Subsequent histopathological studies from my lab (Cao et al., 1998; Lutty, 2000; McLeod and Lutty, 1994) and Fryckowski (Fryczcowski et al., 1988; Fryczkowski, 1988; Fryczkowski et al., 1989) observed loss of choriocapillaris, tortuous blood vessels, microaneurysms, drusenoid deposits on BrM, and choroidal neovascularization. The preponderance of histopathological changes were at and beyond equator. We have also observed that diabetic choroidopathy is an inflammatory disease in that leukocyte adhesion molecules are elevated and PMNs are often associated with sites of vascular loss (Cao et al., 1998; Lutty et al., 1997). Modern imaging techniques, although confined predominantly to subfoveal choroid, have elucidated the extent of choroidopathy clinically and re-affirm the findings of the histopathological studies. Blood flow is reduced in subfoveal choroidal vasculature (Nagaoka et al., 2004; Schocket et al., 2004) and areas of hypofluorescence and late filling undoubtedly represent areas of vascular loss and/or compromise (Shiragami et al., 2002; Weinberger et al., 1998). Perhaps, as a result of vascular insufficiency, the choroid appears to thin in DC unless macular edema is present (Campos et al., 2016; Melancia et al., 2016). EDI-SD OCT and SS OCT have documented the tortuosity and loss in intermediate and large blood vessels in Sattler’s and Haller’s layer (Ferrara et al., 2016; Hua et al., 2013; Murakami et al., 2016) seen previously with histological techniques. The risk factors for DC include diabetic retinopathy, degree of diabetic control, and the treatment regimen (Shiragami et al., 2002). Future studies should also employ angioOCT because loss in CC could be documented with this technique. The severity of DC may be underappreciated in the published accounts of DC assessed with imaging techniques because most of the measurements and imaging are in the posterior pole. However, it is now possible to document DC and quantify these changes clinically. This suggests that DC should be evaluated in future clinical trials of drugs targeting DR because vascular changes similar to those in DR are occurring in DC, which could affect visual function in DR.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge D. Scott McLeod for creation of the figures and his insightful observations on diabetic choroid and Jingtai Cao, Ichiro Fukushima, David Lefer and Carol Merges for their contributions to our studies on diabetic choroidopathy. This work was funded by an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award and a Research to Prevent Blindness Lew Wasserman Merit Award. This study was funded by NIH grants EY023962, EY016151, EY001765, and R01 EY017164.

References

- Adamis AP. Is diabetic retinopathy an inflammatory disease? Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:363–365. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranao RI, Garberi JC, Tesone PA, Rumi RS. Evaluation of neutrophil activity and circulating immune complexes levels in diabetic patients. Horm Metab Res. 1987;19:371–374. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1011827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch F, Miyamoto K, Allport J, Fujita K, Bursell S, LP A, Luscinskas F, Adamis A. Integrin-mediated neutrophil adhesion and retinal leukostasis in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1153–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos A, Campos EJ, Martins J, Ambrosio AF, Silva R. Viewing the choroid: where we stand, challenges and contradictions in diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/aos.13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, McLeod S, Merges CA, Lutty GA. Choriocapillaris degeneration and related pathologic changes in human diabetic eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:589–597. doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova G, Kato S, Tamaki Y, Yamashita H, Nagahara M, Sakurai M, Kitano S, Fukushima H. Choroidal circulation in diabetic patients. Eye (Lond) 2001;15:602–607. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeelpour M, Povazay B, Hermann B, Hofer B, Kajic V, Hale SL, North RV, Drexler W, Sheen NJ. Mapping choroidal and retinal thickness variation in type 2 diabetes using three-dimensional 1060-nm optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5311–5316. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara D, Waheed NK, Duker JS. Investigating the choriocapillaris and choroidal vasculature with new optical coherence tomography technologies. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;52:130–155. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman S, Hatchell D. Enhanced superoxide radical production by stimulated polymorphonuclear leukocytes in a cat model of diabetes. Exp Eye Res. 1992;55:767–773. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90181-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryczcowski A, Sato S, Hodes B. Changes in diabetic choroidal vasculature: scanning electron microscopy findings. Ann Ophthalmol. 1988;20:299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryczkowski AW. Diabetic choroidal involvement: scanning electron microscopy study. Klinika oczna. 1988;90:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryczkowski AW, Hodes BL, Walker J. Diabetic choroidal and iris vasculature scanning electron microscopy findings. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:269–279. doi: 10.1007/BF02280087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima I, McLeod DS, Lutty GA. Intrachoroidal microvascular abnormality, a previously unrecognized form of choroidal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:473–487. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidayat A, Fine B. Diabetic choroidopathy: light and electron microscopic observations of seven cases. Ophthalmology. 1985;67:512–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua R, Liu L, Wang X, Chen L. Imaging evidence of diabetic choroidopathy in vivo: angiographic pathoanatomy and choroidal-enhanced depth imaging. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Le ML, Koizumi K, Esser C, Janicki H, Schraermeyer U, Kociok N, Fauser S, Kirchhof B, Kern TS, Adamis AP. A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Faseb J. 2004;18:1450–1452. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1476fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Mitsiades N, Kirchhof B, Koizumi K, Dohmen S, Adamis AP. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prevent early diabetic retinopathy via TNF-alpha suppression. FASEB J. 2002;16:438–440. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0707fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly LW, Barden CA, Tiedeman JS, Hatchell DL. Alterations in viscosity and filterability of whole blood and blood cell subpopulations in diabetic cats. Exp Eye Res. 1993;56:341–347. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampeter ER, Kishimoto TK, Rothlein R, Mainolfi EA, Bertrams J, Kolb H, Martin S. Elevated levels of circulating adhesion molecules in IDDM patients and in subjects at risk for IDDM. Diabetes. 1992;41:1668–1671. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.12.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Perez V, Ma N, Miyamoto K, Peng H, Liao J, Adamis A. VEGF increases retinal ICAM-1 expression in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1808–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutty GA. Diabetic choroidopathy. Focus on Diabetic Retinopathy. 2000;7:10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lutty GA, Cao J, McLeod DS. Relationship of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) to capillary dropout in the human diabetic choroid. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:707–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutty GA, McLeod DS. Phosphatase enzyme histochemistry for studying vascular hierarchy, pathology, and endothelial cell dysfunction in retina and choroid. Vision Res. 2005;45:3504–3511. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DS, Lefer DJ, Merges C, Lutty GA. Enhanced expression of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin in the diabetic human retina and choroid. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:642–653. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod DS, Lutty GA. High resolution histologic analysis of the human choroidal vasculature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3799–3811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melancia D, Vicente A, Cunha JP, Abegao Pinto L, Ferreira J. Diabetic choroidopathy: a review of the current literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:1453–1461. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K, Khosrof S, Bursell SE, Rohan R, Murata T, Clermont AC, Aiello LP, Ogura Y, Adamis AP. Prevention of leukostasis and vascular leakage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic retinopathy via intercellular adhesion molecule-1 inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10836–10841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T, Uji A, Suzuma K, Dodo Y, Yoshitake S, Ghashut R, Yoza R, Fujimoto M, Yoshimura N. In Vivo Choroidal Vascular Lesions in Diabetes on Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka T, Kitaya N, Sugawara R, Yokota H, Mori F, Hikichi T, Fujio N, Yoshida A. Alteration of choroidal circulation in the foveal region in patients with type 2 diabetes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1060–1063. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.035345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y. In vivo evaluation of leukocyte dynamics in the retinal and choroidal circulation. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;103:910–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querques G, Lattanzio R, Querques L, Del Turco C, Forte R, Pierro L, Souied EH, Bandello F. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography in type 2 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:6017–6024. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schocket LS, Brucker AJ, Niknam RM, Grunwald JE, DuPont J, Brucker AJ. Foveolar choroidal hemodynamics in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Int Ophthalmol. 2004;25:89–94. doi: 10.1023/b:inte.0000031744.93778.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder S, Palinski W, Schmid-Schönbein G. Activated monocytes and granulocytes, capillary nonperfusion, and neovascularization in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:81–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima DT, Adamis AP, Ferrara N, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Allende R, Folkman J, D’Amore PA. Hypoxic induction of vascular endothelial growth factors in retinal cells: identification and characterization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as the mitogen. Mol Med. 1995;1:182–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiragami C, Shiraga F, Matsuo T, Tsuchida Y, Ohtsuki H. Risk factors for diabetic choroidopathy in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:436–442. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger D, Kramer M, Priel E, Gaton DD, Axer-siegel R, Yassur Y. Indocyanine Green angiographic findings in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:238–247. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierusz-Wysocki B, Wysocki H, Siekierka H, Wykretowicz A, Szcaepanik A, Klimas R. Evidence of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) activation in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Leukocyte Biol. 1987;42:519–523. doi: 10.1002/jlb.42.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]