Abstract

Purpose

To examine attitudes toward tobacco control policies among older African American homeless-experienced smokers.

Approach

A qualitative study.

Setting

Oakland, California.

Participants

Twenty-two African American older homeless-experienced smokers who were part of a longitudinal study on health and health-related outcomes (Health Outcomes of People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle Age Study).

Method

We conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with each participant to explore beliefs and attitudes toward tobacco use and cessation, barriers to smoking cessation, and attitudes toward current tobacco control strategies including raising cigarette prices, smoke-free policies, and graphic warning labels. We used a grounded theory approach to analyze the transcripts.

Results

Community social norms supportive of cigarette smoking and co-use of tobacco with other illicit substances were strong motivators of initiation and maintenance of tobacco use. Self-reported barriers to cessation included nicotine dependence, the experience of being homeless, fatalistic attitudes toward smoking cessation, substance use, and exposure to tobacco industry marketing. While participants were cognizant of current tobacco control policies and interventions for cessation, they felt that they were not specific enough for African Americans experiencing homelessness. Participants expressed strong support for strategies that de-normalized tobacco use and advertised the harmful effects of tobacco.

Conclusion

Older African American homeless-experienced smokers face significant barriers to smoking cessation. Interventions that advertise the harmful effects of tobacco may be effective in stimulating smoking cessation among this population.

Keywords: cigarette smoking, homeless adults, smoking cessation, graphic warning labels, smoke-free policies

Purpose

The prevalence of tobacco use among populations experiencing homelessness is between 60% and 80%, almost 5-fold higher than the general population.1,2 High rates of co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders, lack of smoke-free living environments, lack of access to smoking cessation services, and vulnerability to tobacco industry marketing are some of the reasons for the high rates of tobacco use among homeless-experienced adults.3,4 Population-wide tobacco control efforts have yielded declines in the prevalence of smoking in the general population, but these efforts have not led to similar declines among persons who have experienced homelessness, have mental illness and/or substance use disorders, have low educational attainment, or who belong to racial/ethnic minority groups.5 Homeless persons are 2 to 3 times more likely to die prematurely than nonhomeless persons because of factors that contribute to homelessness such as poverty, substance use, tobacco use, and mental illness.6,7 Among these causes, tobacco-related morbidity and mortality are the leading causes of death among persons aged 50 and older.8

In the past 3 decades, there has been a substantial increase in the number of homeless persons aged 50 and older.9–11 The median age of homeless adults increased from 37 years in 1990 to almost 50 years in 2010.9,11 Racial/ethnic minorities are overrepresented in the homeless population, with African Americans comprising 30% to 40% of the population despite making up less than 15% of the general population.12–14

The burden of tobacco use is disproportionately concentrated among racially/ethnically diverse aging populations.15 In particular, older African Americans have a high prevalence of tobacco-related morbidity16,17 and are more likely to die from these diseases compared to non-Hispanic whites.16 In the general population, older smokers are less supportive of anti-tobacco norms and are less successful at quitting despite making similar number of quit attempts as younger smokers.18 Older persons from racial/ethnic minority groups are particularly susceptible to tobacco industry marketing that has normalized the use of tobacco and minimized harms related to smoking.19,20 In our previous study among racially/ethnically diverse older homeless adults, the quit attempt rate was similar to the general population, but the rate of successful cessation was much lower.2

Population-wide tobacco control strategies such as clean indoor air laws and cigarette taxes have been effective in reducing tobacco use in the general population by reducing initiation and increasing cessation, but the beneficiaries of these policies have been persons who belong to higher socioeconomic status.21,22 Graphic warning labels have been shown to be effective in communicating the health effects of tobacco,23 changing attitudes and beliefs related to tobacco use,23 and promoting cessation.24 Clinical interventions that include the provision of behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy have also been effective in reducing tobacco use in the general population.25 Although cigarette taxes have been shown to reduce smoking-related health disparities, other policies and interventions have not shown to reduce health disparities among smokers.26 There is a need for improved understanding of attitudes toward current tobacco control policies and interventions among racially/ethnically diverse older homeless adults’ in order to develop interventions that increase the efficacy of quit attempts among this population. Thus, in this qualitative study, we sought to examine older African American homeless-experienced adults’ perceptions of tobacco use and cessation behaviors and attitudes toward current tobacco control policies and interventions. We focused on how the experience of homelessness, experience related to being a racial/ethnic minority group living in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods, and experience with substance use could influence tobacco use and cessation behaviors.

Approach

This is a qualitative study exploring perceptions of tobacco control policies among older African American homeless-experienced adults.

Setting

The Health Outcomes of People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle Age (HOPE HOME) Study is a longitudinal study of life course events, geriatric conditions, and their associations with health-related outcomes among 350 older homeless adults recruited using population-based sampling14 from homeless encampments, recycling centers, overnight homeless shelters, and free and low-cost meal centers serving at least 3 meals a week in Oakland, California.2

Participants

Participants were eligible if they were English speaking, aged 50 years and older, defined as homeless as outlined in the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act,15 and able to provide informed consent, as determined by a teach-back method.16 The institutional review board of University of California, San Francisco, reviewed and approved all study protocols.

The HOPE HOME study included an enrollment visit, and 6 follow-up visits at 6-month intervals for 3 years. For this substudy on tobacco, we invited African American study participants who had completed their 18-month or 24-month follow-up interviews and who were current smokers (defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and having smoked in the past 30 days) to enroll in the study. We used a purposive sampling technique, based on age, sex, and quit attempts to recruit eligible participants into the study. We informed all eligible participants that this study on tobacco use was independent of the parent HOPE HOME study, and participation was voluntary. We asked participants to return at another time to complete the in-depth interview, and during the interview, staff offered participants breaks to minimize the burden from having to complete lengthy study procedures. Although all participants were homeless at the time of recruitment into the HOPE HOME study, some had obtained permanent supportive housing for formerly homeless adults at the time of the current interview (homeless experienced). After verifying eligibility, trained research staff obtained written informed consent and conducted 60 to 90 minutes, in-depth, semistructured interviews at a community-based site between October 2015 and April 2016. We stopped recruiting participants once we achieved thematic saturation in the interviews. Participants received a $20 gift card to a major retailer for their participation.

Methods

Data Collection

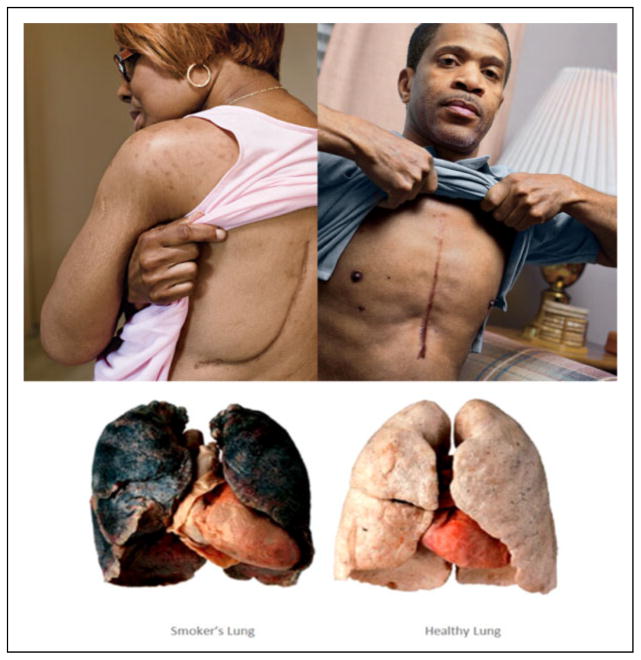

The principal investigator (M.V.) and a multidisciplinary research team familiar with tobacco use in homeless populations developed the in-depth, semistructured interview guide. We relied on the social cognitive theory (SCT) to provide a theoretical framework for the study.27 We adapted constructs from the SCT to identify environmental, behavioral, and personal factors that influenced tobacco use and cessation and perceptions of current tobacco control strategies among older, African American homeless-experienced smokers. We focused on the following topics in the interviews: beliefs related to tobacco use and cessation, barriers to cessation, perceptions of current tobacco control strategies, and strategies to increase interest, self-efficacy, and confidence to quit smoking. We asked about how experiences related to homelessness, with living in poverty, and being part of a racial/ethnic minority group influenced tobacco initiation and maintenance. We asked participants to report their attitudes toward 3 tobacco control policies: raising cigarette prices, graphic warning labels, and smoke-free policies. We presented graphic warning labels that depicted the negative effects of tobacco on the body developed by the Food and Drug Administration (image of damaged lungs) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention Tips from Former Smokers’ Campaign (pictures and stories of Annette and Roosevelt; Figure 1). Participants also reported their attitudes toward individually tailored strategies for cessation including the use of medications or nicotine replacement therapy for cessation, one-on-one or group counseling, Internet-/text-based interventions, or incentives for cessation.

Figure 1.

Images from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tips from Former Smokers’ Campaign (copied from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tips from Former Smokers’ Campaign; http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/stories/stories-by-disease-condition.html) and the Food and Drug Administration graphic warning labels. presented to participants (copied from 2012 Food and Drug Administration proposed Graphic Warning Labels; http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ucm259214.htm).

Participants self-reported age and sex at the enrollment visit for the parent HOPE HOME Study. We extracted information about participants’ tobacco use and cessation history from their most recent structured interviews. We asked current daily smokers to report the number of cigarettes smoked daily.28 For current nondaily smokers, we estimated average daily cigarette consumption based on self-reported numbers of cigarettes smoked on smoking days in the past 30 days. Participants reported how soon they had smoked their first cigarette after waking, which we dichotomized as greater or less than 30 minutes. We asked current smokers about their intentions to quit smoking (never expect to quit, may quit but not in the next 6 months, expect to quit within the next 6 months, and expect to quit within the next month). We asked current smokers to report whether they had stopped smoking for 1 day or longer in the past 6 months because they were trying to quit smoking.

Data Analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis

Audiotaped, in-depth, semistructured interviews were transcribed verbatim by a contracted professional transcription service, and transcribed texts were redacted of any personal identification data. We used Atlas.ti.7 qualitative data analysis software to facilitate efficient coding. We analyzed qualitative data using a grounded theory approach.29 We used the theoretical framework from the SCT and prior research to identify research questions,2 and through iterative processing of the transcripts developed a framework to understand responses to current tobacco control strategies among older African American homeless adults. The objective of the framework was to identify promising interventions for the future.

The 2 interviewers (P.O. and J.W.) coded each other’s transcripts. A secondary coder (K.M.) independently coded all transcripts, and the P.I. (M.V.) reconciled the codes. After independently coding the first 4 transcripts, the research team met to develop the first iteration of the codebook. We used the initial codebook to code subsequent transcripts and met regularly during the coding process to refine the codebook by resolving disagreements in assignment or description of codes. The Cohen Kappa score for inter-rater reliability for agreement in coding among the 4 coders was .61. We further refined and reduced the number of overall codes by grouping them into a short list of inclusive categories and themes and identified linkages between themes to develop a conceptual framework.

Quantitative Data Analysis

We used means (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables for all descriptive variables. We conducted all analyses using Stata, version 11.

Results

We conducted interviews with 22 participants who had completed either their 18-month or 24-month follow-up interviews. The mean age of the participants was 57.2 (SD 3.8) years and 63.6% were male (Table 1). The average daily cigarette consumption was 9.9 cigarettes per day, and 50% (n = 11) reported needing to smoke within 30 minutes of waking. The majority of smokers reported an intention to quit smoking, but few had a plan to do so within the next month. One-third of the participants had made a quit attempt in the past 6 months. In comparison, average daily cigarette consumption for the overall cohort was 8.3 cigarettes per day, 39.4% reported having to smoke within 30 minutes of waking, and 40.2% reported having made a quit attempt in the past year.

Table 1.

Demographic and Smoking Characteristics of Participants.a

| Total n = 22 | |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

| Age | 57.3 (3.7) |

| Male | 14 (63.6) |

| Smoking behaviors | |

| Every day smokers | 14 (63.7) |

| Someday smokers | 6 (27.3) |

| Average daily cigarette consumptionb | 8.8 (6.4) |

| Time to first cigarette in the morning <30 min | 10 (45.5) |

| Quit attempt in the past 6 monthsc | 8 (36.4) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

n = 22

Average daily cigarette consumption is the number of cigarettes smoked on smoking days in the past month.

Intentional quit attempt lasting for 24 hours in the past month.

Qualitative Themes

We identified 7 major themes from the in-depth semistructured interviews: social norms leading to smoking initiation, substance use as a trigger to cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence as a barrier to cessation, homelessness as a barrier to cessation, fatalism as a barrier to smoking cessation, tobacco industry marketing to marginalized populations, and benefits of tobacco policy and interventions. We chose quotes that were illustrative of the themes we identified (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected Quotes Representing Themes.

| Social norms leading to smoking initiation | Interviewer: You started at 4 or 5 [years]. Tell me what that was all about. |

| Participant: My father smoked, my older brother smoked, then all the neighbors smoked and then you’re walking down the street, everybody was smoking so they’d throw a cigarette down and … we’d pick them up and get smoking too … It wasn’t an everyday thing but that’s actually the first time I started picking up cigarettes. But, by 12–14, I was a full fledged smoker, buying my own packs of cigarettes. —Male participant (150) | |

| Substance use as a trigger for cigarette smoking | Participant: I started when I was, maybe 21, we used to smoke marijuana and everybody would light up a cigarette [after]. —Male participant (316) |

| Interviewer: What is good about using cocaine and smoking cigarettes? What is it that is kind of – meshes for you? | |

| Participant: I don’t know. It’s just after I take a hit. The first thing I think about is a cigarette. With cigarettes, you blow out more smoke. You get a lot more than with the crack. It’s also a different taste. It’s definitely a different feeling. Now, I have hit a cigarette and it made me dizzy. But when I hit the crack it’s different cause it gives you like a rush, if it’s decent crack. So I’m out there, I need a cigarette, to kind of mellow it out. Or some weed. | |

| Interviewer: Does the crack intensify or kind of mellow the cigarette smoke? | |

| Participant: The cigarette kind of mellows out the high. | |

| Interviewer: And then what about smoking weed? | |

| Participant: Weed gives me – not a very strong urge for a cigarette, but it does. And they go hand in hand … So I usually want to hit a cigarette after I smoke weed. —Female participant (406) | |

| Nicotine dependence as a barrier to cessation | Participant: I’ve been [smoking daily] for so long. And I’m starting to believe that it’s the nicotine that’s got me addicted because I used to think that I could just quit any time I want to but I find it’s not that easy. |

| Interviewer: How old were you when you first started smoking? | |

| Participant: About maybe 14 or 15. —Male participant (283) | |

| Interviewer: You were talking about the anxiety thing and that [cigarettes] do help people think better? | |

| Participant: Right. So that would be just like a heroin addict, when I get my first [cigarette] in the morning, it helps me think better … and if I’m out of cigarettes and when I wake up in the morning I have to have one. I should’ve kept one cigarette for the morning, so I won’t have to try to run to the store or go to my neighbor and ask for a cigarette … Sometimes I [say] I’m just going to do without and it don’t work … it can mess up a good calm day for me because it just stay in my head —Male participant (152) | |

| Homelessness as a barrier to cessation | Interviewer: What makes it so hard to stop? |

| Participant: Because of where I’m living at. [Crying.] If I weren’t living there I would not be smoking because every time I have my own place I don’t smoke cigarettes. Every apartment I’ve had I didn’t smoke cigarettes because I was comfortable, I was relaxed, I was independent because I was in a normal living environment. Now I’m in this environment [single room occupancy hotel] and I hate it and I can’t do anything about it, and that cigarette be calling me. —Female participant (348) | |

| Interviewer: So as soon as you get a place you think that’s going to be— | |

| Participant: I think that it’s going to benefit me a lot as far as stopping smoking, I really do because I won’t be running the streets, you know, I won’t be worried about what the next day is going to bring. … Yeah, I would be so much more at ease and I could really work on my quitting. —Male participant (283) | |

| Interviewer: Let’s say you got into housing, you were able to get into housing, and they had a no- smoking policy. | |

| Participant: Oh, I can respect that. I’d just be having’ me a place – I would quit cold, like yesterday. I really would, but I’d be so thankful to have me a place of my own. When I do, just keep it. It wouldn’t be a problem in the world. —Female participant (252) | |

| Fatalism as a barrier to cessation | Participant: I don’t know, they say don’t bother something that isn’t bothering you, it might get worse if I stop. My body be so used to it, then my body going to go through this thing, “What’s up? Where’s my smoke at?” you know, and it haven’t made me feel bad, I don’t have lung cancer or, you know, basically mine is in my old bones and my back, so it never caused me a problem that is apparent to me, and I’m 67. —Female participant (193) |

| Participant: They told me if I keep smoking it’s going to hurt me in the long run but I feel like the damage might be already done … I’ve known people who were, alcoholics and drug addicts and smoked cigarettes, and the minute all that was taken away from them they got [more ill]. —Male participant (316) | |

| Tobacco industry marketing to poor African American populations | Interviewer: And do you feel like advertising or anything is being targeted in a different way, or in any way, at the African-American community? |

| Participant: They used to advertise Kool’s for the African-American – they know a lot of black folks smoke Kool’s. They smoke Salems. Now we smoke Newports. But I don’t see those advertisements up too much. They may sneak ‘em in in the movie. ‘Cause I know Samuel Jackson smokes Newports. So they figure hey, since he smokes Newports, they must be a pretty good brand, so everybody smokes Newports. —Female participant (438) | |

| Participant: If they would do less advertising in the mom and pop corner markets, in the corner liquor stores … So with less advertising and these cigarette companies stop putting that, especially in the ghetto or in lower income [neighborhoods], that would help a great deal. —Female participant (353) | |

| Participant: It’s like with the alcohol and the cigarettes and all that, okay, they make their money more with people that live in the ghetto, that, you know, it’s a diverse community, but they’re selling the liquor, they’re selling the wraps, they’re selling the cigarettes, and all that, it’s like, okay, and it’s always going to be the people that can’t really afford it. Now you can go to where you get middle class to rich class, okay, now you’re going to see less liquor stores, less advertisement because it’s a “Keep America Beautiful” thing so they don’t want to make that color and they don’t want to see a liquor store on the corner of, where the mansions are. —Female participant (353) | |

| Impacts of tobacco policy and cessation interventions | Interviewer: How do you feel about raising the cigarette prices to levels where it’s really high, would that be helpful to help people quit or would they still find ways to— |

| Participant: They’ll still find ways, people who smoke, they’ll go out there and pick up a butt on the street. They’re going to find a way no matter what. —Male participant (145) | |

| Interviewer: So the first is a side by side on two sets of lungs, ones a smoker’s lungs and the others a healthy lung. | |

| Participant: Well, naturally … you can tell how unhealthy that is, and that tells me right there that this person doesn’t have a long time to live. Your lungs got to do with everything, and if that’s what tobacco is doing to them then more people need to see these pictures. It scares the hell out of me when I look at it. More people need to see it. | |

| Interviewer: Why? | |

| Participant: Because maybe it will wake them up, let them know, “Hey, I really need to quit smoking because all,” I look at all the years I’ve been smoking and my doctor tells me my lungs are good but that doesn’t mean that they’re not getting bad because, you know, looking at this, that’s really terrible, man, that scares the hell out of me when I look at it … There’s a lot of people, that should be a wakeup call … | |

| Interviewer: So you think people aren’t really that aware what they’re doing to themselves or they just need to see the visual. | |

| Participant: No, I don’t think that they really give it a second thought, you know, but if they seen stuff like this, that would give them something more to think about. Especially the younger generation, yeah, I would recommend putting that on a pack of cigarettes … They definitely need more advertisement on what cigarettes can do to you. —Male participant (283) Participant: … If they advertise more things like the pictures you were showing, I think that’d do a lot, I really do. | |

| Interviewer: Where would we advertise those pictures? | |

| Participant: Probably on TV and the newspaper. … at the recycle center because everybody [that] goes there just about smokes cigarettes. I know they had an effect on me. —Male participant (154) | |

| Interviewer: And how do you feel about policies like that, do you think they’re a good idea or not, that you can’t smoke within certain areas and you got to go outside? | |

| Participant: Yeah, I think it’s a good idea because it makes a smoker realize that he can’t just light up anywhere he wants to, now he have to look around and see, “Can I light up here?” And that give you more time to think, “Oh, well, I can wait for a cigarette until later.” So that could probably help [to cut down]. —Male participant (247) | |

| Interviewer: If you had a choice, and you’re staying in a van right now, if you could get into senior housing … But they did have a really strict no smoking policy, but you could get in if you’d get out of the van. | |

| Participant: Well, you know what the thing about that is, in that instance, I would be okay with it because, yeah, it would get me off the streets, at least I’ll be indoors permanently, I’d find a way to deal with [smoking] —Male participant (316) |

Social Norms Leading to Tobacco Initiation

The consensus among participants was that community social norms during their childhood supported smoking. Almost all participants reported initiating smoking before they were 18. The majority of participants reported that seeing family members smoking, especially a parent, was one of the primary reasons for initiating cigarette smoking (Table 2). A few participants reported the influence of peer pressure, referring to the camaraderie associated with social smoking as one of the other reasons for initiating tobacco use. Three participants reported initiating tobacco use at an early age during their time in the military.

Substance Use as a Trigger for Cigarette Smoking

Participants described the use of illicit substances, in particular marijuana use, during adolescence or young adulthood as serving as a gateway for tobacco use (Table 2). Almost all participants reported that the co-use of tobacco with other illicit substances such as heroin, cocaine, alcohol, or marijuana was a significant reason for maintaining tobacco use. Alcohol use or heroin use were often a cue for cigarette smoking, and participants who reported drinking alcohol or smoking heroin not only had an increased urge to smoke but also increased consumption. Participants who reported using cocaine discussed the effects of nicotine as “mellowing” the “high” from cocaine use (Table 2). Marijuana smoking was common, and most participants reported that cigarette smoking “intensified the high” from marijuana smoking and vice versa. One participant reported that the use of other substances was her only trigger for cigarette smoking, and if she were not getting “high” from cocaine or marijuana, she would not be smoking cigarettes.

Nicotine Dependence as a Barrier to Cessation

Participants reported heavy nicotine dependence as a trigger for continued tobacco use and as a barrier to cessation. Several participants described changes to cigarette composition (eg, the use of filters, increased nicotine) that made smoking cessation more challenging now compared to a few decades ago. Almost all participants reported smoking daily and many reported having the need to smoke within 30 minutes of waking, indicators of heavy nicotine dependence. Many participants reported that initiating smoking at a young age and daily smoking were some of the barriers to cessation (Table 2). Several participants reported strong withdrawal symptoms as a trigger for smoking maintenance and likened tobacco’s effects to that of “a drug” that they “needed to have” (Table 2).

Homelessness as a Barrier to Cessation

The majority of participants described stress as a normative experience of homelessness and a common barrier to smoking cessation. Participants expressed the need to smoke to cope with financial stressors, stressful interactions with family or friends, anxiety or other mental health disorders, death of family members or friends, and severe pain. Several participants discussed the stress associated with staying in emergency shelters or unstable housing as one of the primary reasons for continuing to smoke. Some participants who had been permanently housed but who were living in suboptimal conditions also described poor housing conditions as a barrier to cessation (Table 2). Participants reported that having access to smoke-free housing would be a strong motivator for tobacco cessation.

Fatalism as a Barrier to Cessation

Overall, participants exhibited strong motivation to quit smoking but were not ready to take action. Participants reported receiving advice to quit from friends, family, and health-care providers, but few acted on the advice. A few participants exhibited fatalistic views around smoking cessation because they had smoked for decades without experiencing any adverse effects (Table 2). Some participants reported continuing to smoke in spite of having tobacco-related chronic diseases including emphysema, asthma, or cardiovascular disease. These participants expressed cognitive dissonance when recognizing the harm that tobacco smoking caused while remaining unable or unwilling to quit smoking.

Tobacco Industry Marketing to Poor African American Populations

Almost all participants reported smoking menthol cigarettes, with “Kools,” “Newports,” “Fortunas,” or “Mavericks” being the most common brands. Participants reported that their preference for menthol cigarettes was a reflection of the heavy marketing of these products by the tobacco industry toward the African American community (Table 2). Participants reported that exposure to marketing for tobacco products was much more prevalent in their low-income communities compared to higher income communities, which created a significant barrier to cessation (Table 2).

Impacts of Tobacco Policy and Interventions

In response to questions on raising cigarette prices, the consensus among participants was that people would find a way to continue smoking irrespective of the price. To circumvent the high price of cigarettes, participants reported having to rely on low cost, generic cigarettes or roll-your-own tobacco, and many resorted to high-risk practices like smoking cigarette butts. Several participants reported having to recycle bottles or cans in order to generate income to purchase cigarettes. “Bumming” or sharing cigarettes with friends was considered a normative behavior. Participants reported that they had thought about quitting smoking when the price of cigarettes in California was much lower than the current price, but they had continued to smoke despite the price increase by reducing consumption and inhaling more deeply from each cigarette or not sharing cigarettes with friends (Table 2).

Almost all participants reported that if they were exposed to graphic warning labels regularly, it would motivate them to reduce their smoking or quit completely. Participants had a preference for warning labels that depicted the negative effects of smoking on the body and had more of a “shock value” compared to the less provocative warning labels. Two participants reported that the graphic warning labels did not trigger their own interest to quit smoking; however, they did see the value of using these labels on cigarette packs and wide dissemination of the images to minimize initiation of tobacco products by youth and young adults (Table 2).

Participants reported that these warning labels needed to be more widely advertised including on billboards, on packs of cigarettes, at the point of sale, in smoke shops, in liquor stores, in grocery stores, and in low-income communities where there was a higher density of convenience stores that sell alcohol and tobacco products (Table 2).

The consensus among participants was that smoke-free policies were important to protect nonsmokers and children from the harms of secondhand smoke. Most participants reported that if they had access to housing that was smoke-free, they would modify their smoking behaviors (eg, smoke outside) to keep their housing. Some participants acknowledged that the policy itself would not lead to smoking cessation but could potentially lead to reduced consumption. Participants were knowledgeable about smoke-free ordinances in their communities and also the fines that were levied for littering public spaces with cigarette butts or for smoking in nonsmoking zones. A few participants discussed the effects of the policy on reducing smoking behaviors. One of the participants reported that when he was staying in an emergency shelter that restricted smoking at night, he had no desire to smoke because he was not “in a smoking environment” (Table 2).

Participants were more enthusiastic about tobacco policies that addressed tobacco effects on the society than individually tailored strategies for cessation. There were mixed opinions about whether nicotine replacement therapy or medications were helpful in aiding cessation. A minority of participants who had used nicotine replacement therapy or medications in a prior quit attempt acknowledged that they had found the medications unhelpful because they had not used them as prescribed. Some participants were unwilling to use these medications because of fear of being exposed to additional chemicals or being more addicted to nicotine. Most participants were not enthusiastic about attending group or one-on-one counseling sessions or receiving Internet-based counseling or text messages for cessation. However, a few participants did report that they would find group counseling helpful because they could learn from other people’s experiences on quitting smoking. Opinions were also mixed regarding receiving financial incentives for smoking cessation. Some participants believed that incentives could trigger a change in smoking and others reported that they would use the extra money to buy more cigarettes. Despite these differences of opinion about the efficacy of individually tailored strategies for cessation, there was consensus that more needed to be done to promote existing policies and interventions for cessation in this population.

Framework to Understand Response to Current Tobacco Control Strategies

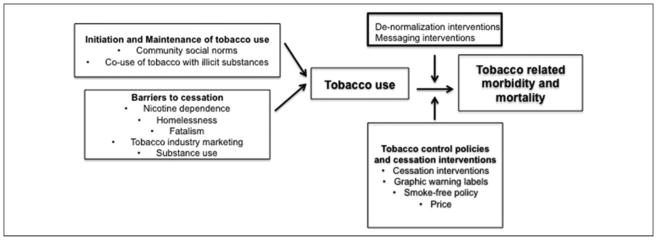

Findings from our study suggested that initiation and maintenance of tobacco use were in large part due to community social norms supportive of smoking and the co-use of tobacco with illicit substances. Barriers to cessation included nicotine dependence, homelessness, fatalistic attitudes toward cessation, substance use, and exposure to tobacco industry marketing. Although current tobacco control policies and interventions aimed at reducing tobacco-related morbidity and mortality are effective for the general population, messages and interventions targeting homeless populations are needed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Framework to understand response to current tobacco control strategies among older African American homeless-experienced adults.

Conclusion

In this study among older African American adults who had experienced homelessness, strong community social norms supportive of smoking, experiences related to homelessness, high levels of nicotine dependence, co-use of illicit substances and tobacco use, exposure to tobacco industry marketing, and fatalism were some of the factors that led to tobacco initiation and maintenance. The lack of targeted, individually tailored cessation strategies and limited exposure to tobacco control policies may have contributed to the increased rates of tobacco use among older homeless-experienced African American smokers.

Participants reported that the normative experiences of belonging to a racial/ethnic minority group and being homeless were strong motivators of initiating and maintaining tobacco use. Despite the fact that African American smokers are lighter smokers than white smokers, African Americans are less successful at quitting smoking.30 Exposure to tobacco industry marketing of menthol products played a significant role in promoting tobacco use among participants in our study. Over 80% of African American smokers consume menthol cigarettes.31 Over the past 3 decades, the tobacco industry has selectively targeted low-income, predominantly African American communities for concentrated menthol cigarette marketing.32,33 Aside from marketing specifically to low-income African Americans, the tobacco industry also has a history of marketing to homeless adults in order to hold on to a clientele that they perceived to be susceptible to marketing tactics because of underlying mental health and substance use disorders.4 Although participants in our study did not report being targeted by the industry because of being homeless or having a mental health disorder or substance use disorder, they did acknowledge the industry’s efforts in making tobacco products more addictive over their life span. This was evidenced by the fact that a vast majority of participants initiated smoking during their childhood and continued to smoke despite awareness of the harms related to tobacco use.

Almost all participants reported living in socioeconomically deprived communities where tobacco use was normalized. Participants discussed the absence of smoke-free policies and the increased tobacco outlet density in low-income communities where they had spent their childhood or young adulthood as other barriers to cessation. These findings highlight the need for interventions that de-normalize tobacco use in low-income communities. Smoke-free policies in homeless shelters, low-income public housing or supportive housing for formerly homeless adults,34 structural interventions that minimize the pervasiveness of tobacco industry marketing at the point of sale, and regulatory policies that restrict the marketing and sales of menthol cigarettes could reduce initiation and maintenance of tobacco use among homeless adults. Cessation interventions that account for tobacco outlet density in low-income communities22,35,36 also hold promise as de-normalizing interventions for homeless populations. Although the provision of smoke-free policies in shelters or supportive housing is an integral component of smoking cessation care, providing treatment for cessation in the form of medications and counseling could help people adhere to these policies and minimize risk of evictions.

Consistent with previous studies,14,37,38 our findings suggested that substance use during childhood or adolescence was associated with the initiation and maintenance of tobacco use during adulthood. Participants demonstrated “cue-induced craving” for cigarettes after using specific substances or after exposure to the sight or smell of cigarettes.39,40 Participants also demonstrated a learned memory of the physiologic and emotional experience of co-using other substances and cigarettes, which not only served as a trigger for smoking but also posed challenges to quitting smoking without also quitting other substances.41 The findings from our study and others42–44 highlight the importance of understanding the role of substance use in prequit intentions and postquit success in order to develop interventions for smoking cessation.

Participants expressed skepticism that cigarette prices would motivate cessation behaviors, despite evidence that suggests that cigarette taxes are among the most effective policies to encourage smoking cessation.45 This skepticism may stem from the fact that raising cigarette prices may increase financial burden without leading to a change in smoking behaviors among a population with limited financial resources.46

Participants expressed enthusiasm for increased exposure to graphic warning labels as a motivator for smoking cessation. Participants suggested placing these labels on cigarette packs and in their immediate environments as cues for cessation. Warning labels and anti-tobacco media campaigns are effective strategies to inform smokers about the harms of tobacco use and to encourage smokers to quit smoking.47 Graphic warning labels are more effective than text-only messages in communicating the health effects of tobacco,23,48 in increasing quit intentions,23 and in promoting successful cessation.24,49 A study among older adults in the general population suggested that positively framed messages that outlined the long-term benefits of cessation were more appealing than negatively framed messages that depicted the harms of smoking.20 In our study, participants believed that messages that depicted the negative effects of tobacco on the body could be more effective than those that emphasized the positive effects of smoking cessation. Future studies should explore perceptions around positively framed messages and graphic warning labels. These findings highlight the potential for anti-tobacco graphic warning labels and messages as primary or adjunctive interventions for cessation in this population.

Although participants expressed mixed sentiments about the efficacy of individually tailored strategies for cessation such as medications for cessation or counseling, participants also acknowledged inconsistent use of these treatment modalities. Some participants expressed a preference for group counseling, and this may be due to prior experiences with attending group counseling for substance use treatment. As in previous studies among African American smokers,50,51 participants expressed concerns about the safety of nicotine replacement therapy and were suspicious of interventions promoted by the medical community. Clinical practice guidelines highlight the importance of medications and behavioral counseling as the mainstay of tobacco use treatment.52 One of the primary reasons for the lack of efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy or counseling is incomplete adherence to treatment.52 Our findings suggest the need for consistent access to both medications and counseling and for increased education on the efficacy and safety of treatment modalities for smoking cessation in this population.

Our study had several limitations. Findings from our study were specific to older African American homeless adults and may not be generalizable to other populations of homeless adults or to other participants in the HOPE HOME cohort. The views of the research-engaged participants in this study may not be representative of the research-naive public. We used a purposive sampling technique to recruit participants, increasing the likelihood of selection bias. We did not show positively framed messages and were not able to assess participants’ views on these types of messages. Although there could have been bias in the coding of the interviews, we minimized bias by having independent coders and found good agreement in these code selections.

Our study is timely because it suggests several ways in which implementation and dissemination efforts can more effectively reach a seriously underserved subgroup, namely homeless-experienced African Americans.53 Our findings suggest that de-normalization and messaging interventions that recognize the larger social and environmental context of tobacco use may play a role in reducing tobacco use among racially/ethnically diverse older homeless-experienced adults.

SO WHAT?

What is already known on this topic?

The homeless population is aging. Approximately 70% of older homeless adults are smokers. African American adults are overrepresented in the aging homeless population and bear a disproportionate burden of tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. Prior research has shown that racially/ethnically diverse older adults who have experienced homelessness are interested in quitting smoking.

What does this article add?

Little is known about attitudes toward tobacco control policies among older African American homeless-experienced adults. Our study found that older African American homeless-experienced adults are supportive of interventions that advertise the harmful effects of tobacco use. Participants were also supportive of smoke-free policies in shelters and in permanent supportive housing or low-income, multi-unit housing that de-normalize tobacco use.

What are the implications for health promotion or practice or research?

Smoke-free policies that reduce exposure to tobacco use and graphic warning labels that depict the negative effects of tobacco on the individual and society are potential implementation and dissemination strategies for successfully reaching homeless-experienced African Americans.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff at St Mary’s Center and the HOPE HOME Community Advisory Board for their guidance and partnership.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (P30AG015272 [Vijayaraghavan, Weeks], K24AG046372 [Kushel], R01AG041860 [Ponath, Olsen]).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

These funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Baggett TP, Rigotti NA. Cigarette smoking and advice to quit in a national sample of homeless adults. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(2):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vijayaraghavan M, Tieu L, Ponath C, Guzman D, Kushel M. Tobacco cessation behaviors among older homeless adults: results from the HOPE HOME study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(8):1733–1739. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apollonio DE, Malone RE. Marketing to the marginalised: tobacco industry targeting of the homeless and mentally ill. Tob Control. 2005;14(6):409–415. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pampel FC. The persistence of educational disparities in smoking. Soc Probl. 2009;56(3):526–542. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, O’Campo PJ, Dunn JR. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b4036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, et al. Mortality among homeless adults in Boston: shifts in causes of death over a 15-year period. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):189–195. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baggett TP, Chang Y, Singer DE, et al. Tobacco-, alcohol-, and drug-attributable deaths and their contribution to mortality disparities in a cohort of homeless adults in Boston. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1189–1197. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culhane DP, Metraux S, Byrne T, Stino M, Bainbridge J. The age structure of contemporary homelessness: evidencen and implications for public policy. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy. 2013;13(1):228–244. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kushel M. Older homeless adults: can we do more? J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):5–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1925-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn JA, Kushel MB, Bangsberg DR, Riley E, Moss AR. BRIEF REPORT: the aging of the homeless population: fourteen-year trends in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):775–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285(2):200–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(7):1326–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuyemi KS, Goldade K, Whembolua GL, et al. Smoking characteristics and comorbidities in the power to quit randomized clinical trial for homeless smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):22–28. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaCroix AZ, Omenn GS. Older adults and smoking. Clin Geriatr Med. 1992;8(1):69–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health disparities experienced by black or African Americans – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(1):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. CMAJ. 2001;164(2):229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Messer K, Trinidad DR, Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation rates in the United States: a comparison of young adult and older smokers. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):317–322. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce JP. Tobacco industry marketing, population-based tobacco control, and smoking behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(6 suppl):S327–S334. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cataldo JK, Hunter M, Petersen AB, Sheon N. Positive and instructive anti-smoking messages speak to older smokers: a focus group study. Tob Induc Dis. 2015;13(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12971-015-0027-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce JP, Gilpin EA, Emery SL, et al. Has the California tobacco control program reduced smoking? JAMA. 1998;280(10):893–899. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierce JP, White VM, Emery SL. What public health strategies are needed to reduce smoking initiation? Tob Control. 2012;21(2):258–264. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond D, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM, McNeill A, Driezen P. Text and graphic warnings on cigarette packages: findings from the international tobacco control four country study. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(3):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mead EL, Cohen JE, Kennedy CE, Gallo J, Latkin CA. The role of theory-driven graphic warning labels in motivation to quit: a qualitative study on perceptions from low-income, urban smokers. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:92. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1438-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiore MCBW, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: A Quick Reference Guide for Clinicians. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown T, Platt S, Amos A. Equity impact of interventions and policies to reduce smoking in youth: systematic review. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e98–e105. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Delaimy WK, Edland S, Pierce JP, et al. California Tobacco Survey. UC San Diego Library Digital Collections; 2015. [Accessed August 31, 2017]. California Tobacco Survey (CTS) 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.6075/J0KW5CX7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss ALCJ. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, White MM, Emery SL, Messer K. A nationwide analysis of US racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):699–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caraballo RS, Asman K. Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Tob Induc Dis. 2011;9(suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardiner PS. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(suppl 1):S55–S65. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4 suppl):10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vijayaraghavan M, Hurst S, Pierce JP. A qualitative examination of smoke-free policies and electronic cigarettes among sheltered homeless adults. Am J Health Promot. 2017;31(3):243–250. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.150318-QUAL-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cantrell J, Anesetti-Rothermel A, Pearson JL, Xiao H, Vallone D, Kirchner TR. The impact of the tobacco retail outlet environment on adult cessation and differences by neighborhood poverty. Addiction. 2015;110(1):152–161. doi: 10.1111/add.12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson NA, Lowe JB, Reid RJ. Tobacco outlet density, cigarette smoking prevalence, and demographics at the county level of analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(11):1627–1635. doi: 10.1080/10826080500222685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi HY. Early adolescent patterns of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana polysubstance use and young adult substance use outcomes in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Vittinghoff E, Bangsberg DR, Mias-kowski C, Kushel MB. Smoking behaviors in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):535–543. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0576-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erblich J, Montgomery GH. Cue-induced cigarette cravings and smoking cessation: the role of expectancies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(7):809–815. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drummond DC. Theories of drug craving, ancient and modern. Addiction. 2001;96(1):33–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363–371. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1511480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Businelle MS, Ma P, Kendzor DE, et al. Predicting quit attempts among homeless smokers seeking cessation treatment: an ecological momentary assessment study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(10):1371–1378. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lam CY, Businelle MS, Cofta-Woerpel L, McClure JB, Cincir-ipini PM, Wetter DW. Positive smoking outcome expectancies mediate the relation between alcohol consumption and smoking urge among women during a quit attempt. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(1):163–172. doi: 10.1037/a0034816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reitzel LR, Kendzor DE, Nguyen N, et al. Shelter proximity and affect among homeless smokers making a quit attempt. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(2):161–169. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffman SJ, Tan C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:744. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2041-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baggett TP, Tobey ML, Rigotti NA. Tobacco use among homeless people – addressing the neglected addiction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):201–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1301935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20(5):327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noar SM, Hall MG, Francis DB, Ribisl KM, Pepper JK, Brewer NT. Pictorial cigarette pack warnings: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):341–354. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):905–912. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carpenter MJ, Ford ME, Cartmell K, Alberg AJ. Misperceptions of nicotine replacement therapy within racially and ethnically diverse smokers. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(9–10):885–894. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30444-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yerger VB, Wertz M, McGruder C, Froelicher ES, Malone RE. Nicotine replacement therapy: perceptions of African-American smokers seeking to quit. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(2):230–236. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiore MCJC, Baker T, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knudsen HK. Implementation of smoking cessation treatment in substance use disorder treatment settings: a review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(2):215–225. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1183019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]