Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to analyze the effects of culture on the creative and stylistic features children employ when producing narratives based on wordless picture books.

Method

Participants included 60 first- and second-grade African American, Latino American, and Caucasian children. A subset of narratives based on wordless picture books collected as part of a larger study was coded and analyzed for the following creative and stylistic conventions: organizational style (topic centered, linear, cyclical), dialogue (direct, indirect), reference to character relationships (nature, naming, conduct), embellishment (fantasy, suspense, conflict), and paralinguistic devices (expressive sounds, exclamatory utterances).

Results

Many similarities and differences between ethnic groups were found. No significant differences were found between ethnic groups in organizational style or use of paralinguistic devices. African American children included more fantasy in their stories, Latino children named their characters more often, and Caucasian children made more references to the nature of character relationships.

Conclusion

Even within the context of a highly structured narrative task based on wordless picture books, culture influences children’s production of narratives. Enhanced understanding of narrative structure, creativity, and style is necessary to provide ecologically valid narrative assessment and intervention for children from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Keywords: narrative, cross-cultural, wordless picture book

Storytelling is a means by which people across cultures communicate information; reveal personal events; express emotions; teach lessons; and transmit history, traditions, thoughts, and beliefs from one generation to another. Moreover, storytelling provides an important venue for entertainment. From an early age, children are immersed in various types of storytelling activities, including oral narratives at home, at school, in their communities, and through television, movies, and books. Children describe routine events through scripts, narrate play through event-casts, talk about past experiences through personal narratives, and eventually narrate events that include fictional elements through stories (Hudson & Shapiro, 1991). The relative emphasis on these experiences within narratives is related in part to cultural expectations and experiences.

The importance of storytelling ability also extends to children’s academic achievement. Research indicates that narrative skill is a robust predictor of school success (Feagans & Appelbaum, 1986; Hedberg & Westby, 1993; Westby, 1984). Consequently, speech-language pathologists (SLPs) often incorporate narrative tasks, typically using fictional stories based on pictures or picture books, into assessment and intervention practices (Finestack, Fey, Sokol, Ambrose, & Swanson, 2006; Gillam, McFadden, & van Kleeck, 1995; Gillam & Pearson, 2004; Hayward & Schneider, 2000; Justice et al., 2006; L. Miller, Gillam, & Peña, 2001; Swanson, Fey, Mills, & Hood, 2005). Given the predominance of using storybook tasks in clinical practice, it is important to develop an understanding of the potential influence of culture on children’s storybook narration.

Cultural Infusion

Despite the universality of storytelling, narrative content, structural organization, and functions vary between and within cultural communities (Berman & Slobin, 1994; Heath, 1982; McGregor, 2000). In this context, content refers to the ideas, goals, and themes children use in narration; structural organization refers to the flow, construction, and macro-level patterns of stories; and function focuses on the intent or purpose of the narrative.

Content

Children develop event knowledge through social interactions and repeated experiences, and they learn acceptable conventions for relating this content in their discourse (Gutiérrez-Clellen & Quinn, 1993; Hudson & Shapiro, 1991). A socioconstructivist view of learning considers that children internalize input from social activities and interactions in the form of words, images, and patterns (Rogoff, 2003). For example, children whose mothers include more elaboration when reminiscing also use a more elaborative style to relate past events than their peers do (Haden, Haine, & Fivush, 1997).

Narrative content also reflects important sociocultural ideas and perspectives. Themes that emerge in fictional and personal narratives reflect the distinct goals of the narrators’ culture and are illustrative of Hofstede’s (1986, 2001) individualism–collectivism framework. Wang and Leichtman (2000), for example, found that Chinese children’s narratives focused more on themes related to social engagement, morals, and authority than those of American children. The stories of Chinese children included instances of characters providing help to one another, story endings featuring positive relationships between characters, and references to the protagonist’s proper behavior and moral character. Many of these themes are consistent with a collectivistic orientation. In contrast and consistent with individualism, American children showed a somewhat stronger orientation to character autonomy, making many references to the protagonist’s personal needs, preferences, dislikes, and avoidances.

Consistent with the notion of collectivism, the emphasis on family (familismo) and family relationships has emerged as a dominant theme in the personal narratives of preschool and kindergarten Latino children of Caribbean, Mexican, Central, and South American descent (Cristofaro & Tamis-LeMonda, 2008; McCabe & Bliss, 2004–2005). Of particular interest is that in these co-constructed stories, the parents often chose the topic. Approximately 80% of the narratives were shared stories about a family-centered event or experience. Scaffolding questions often included naming family members present at the event and helping the child understand how family members were related. As a subtheme, helpful and appropriate behavior toward family members often emerged.

From a collectivistic perspective, expression of knowledge focuses on social relationships. In contrast, in an individualistic perspective, expression of knowledge focuses on scientific facts and description (see Greenfield, Quiroz, & Raeff, 2000). In narrative expression, we propose that these perspectives may also be manifested in the creative content of the narrative, and to some extent, the organizational style.

Structural organization

Structural organization is influenced by both context and culture. Although children bring their individual experiences to a narrative task, the context influences how much structural variability one might observe in children’s stories. Personal narratives are relatively less constrained in terms of content and construction compared to books, which constrain the topic and order of narrative elements. Thus, in evaluation of cultural influences on children’s narratives, it is critical to consider the story context.

Michaels (1981) first identified topic-associating (TA) and topic-centered (TC) stories based on her investigation of first-grade African American and Caucasian children’s personal narratives during classroom sharing time. She defined TA stories as being organized around a series of episodes implicitly linked to some person or theme. In these stories, narrators focus on events as related to social interactions and engage their listeners by using an interactional style (consistent with collectivism). In contrast, TC stories are structured around a single topic or closely related topics and focus on the facts of the story in the order in which they occur (consistent with individualism). Michaels observed that African American children in her sample typically produced TA narratives, whereas Caucasian children typically produced TC narratives. Although these descriptions of story types were developed to identify differences in personal narratives, there is some evidence for cultural differences in structural organization of fictional narratives. For example, Celinska (2009) found that although African American and Caucasian students produced fictional narratives with similar length and structure, differences emerged between the groups depending on narrative context. For example, the episodes of the African American students’ personal narratives were shorter, yet their personal and fictional stories included more episodes overall, which Celinska interpreted as being more closely tied to a TA style.

Studies of Latino children’s personal narratives have also suggested variation in narrative structure in comparison to other cultural groups (Berman & Slobin, 1994; Gutiérrez-Clellen & Heinrichs-Ramos, 1993; Melzi, 2000; Silva & McCabe, 1996). Recognizing that the pan-Latino population consists of diverse groups who merit individual regional, linguistic, and sociocultural considerations, some core discourse patterns have been observed in the literature. Generally, these styles of narration are consistent with Michaels’ (1981) description of topic association (McCabe, 1996). For example, Melzi (2000) found that Central American mothers focused on scaffolding their preschoolers’ personal narratives into an opportunity for conversation, whereas European American mothers guided their children toward accurate sequential organization. In a comparison of chronicity in the personal narratives of Spanish-speaking Andean children and U.S. Midwestern English-speaking children, Uccelli (2008) found that the Andean children deviated from a sequential chain of events. This deviation served to highlight a point, include retrospection or flashback, or foreshadow an event. These findings were consistent with Rodino, Gimbert, Perez, Craddock-Willis, and McCabe (1991; in Uccelli, 2008, and Bliss & McCabe, 2008), who reported that Central American and Caribbean Latino children in New York used more evaluation and description than event sequences in their personal narratives.

Function

The purposes narratives serve are also influenced by culture. Bloome, Katz, and Champion (2003) classified narratives as text and narratives as performance. There are parallels between TC and narratives as text, and between TA and narratives as performance; however, Michaels’ (1981) classification system has a particular emphasis on structural organization, whereas Bloome and colleagues’ system has a stronger focus on narrative function. Analysis of narratives as performance considers the narrator’s delivery style as valued by the listeners and the cultures and institutions into which they are socialized (Bauman & Briggs, 1990; Bauman & Sherzer, 1975; Cortazzi, 1992). For example, Nichols’ (1989) study of upper elementary African American children’s fictional narratives documented the inclusion of characters’ quotations and a strong interactional component between the audience and narrator, consistent with a narrative as performance style of storytelling.

High-point analysis, although concerned with the resolution of the point of the story, also considers the expression of personal perspective (Labov, 1972). The evaluative stance and “expressive elaboration” of the narrator help the audience engage with the story (Ukrainetz & Gillam, 2009). Discourse devices such as direct speech and intonational changes may be used to create drama in narratives rated as high quality (Ulatowska, Streit-Olness, Samson, Keebler, & Goins, 2004). Bloome et al. (2003) pointed out that a coherent, orderly narrative text is not necessarily delivered in an engaging performance. Likewise, an engaging narrative may not constitute a strong narrative text. Yet, narrative text and performance are highly interdependent. Multiple approaches to narrative analysis have begun to capture some of the complexities of diverse narrative styles. As a result, when analyzing microstructural differences in narratives across cultural groups, it is also important to consider the impact of story genre on children’s stories.

Effects of context/genre

Research indicates that the narrative context/genre impacts the content, structure, and style of children’s stories. Relative to children from culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) backgrounds, context appears to influence the infusion of culture into stories. Most cross-cultural research has investigated children’s personal and fictional narration. At the macrostructural level, a TC style has been observed in the personal narratives of both African American and Caucasian children (Champion, Seymour, & Camarata, 1995; Hyon & Sulzby, 1994; C. Peterson & McCabe, 1983). In fact, Hyon and Sulzby (1994) conducted a study similar to Michaels’ (1981) and found that, although some African American kindergartners produced TA narratives during uninterrupted sharing time, this was not the dominant style. Approximately one-third of the personal narratives were classified as TA, and slightly more than half were classified as TC. The remaining children’s narratives did not fall into either category.

In a more detailed microstructural analysis comparing African American and Caucasian children’s personal and fictional stories, Celinska (2009) found that both culture and genre impacted children’s stories. When recounting personal stories, African American children elaborated on internal responses to an initiating event more often than their Caucasian counterparts, although this was not the case in fictional stories. The elaboration served to emphasize motivating factors in characters’ actions. In another study with African American children, Champion (1998) found that different types of story prompts elicited different story structures within the category of personal narratives. For example, children were more likely to produce a linear story after the examiner first modeled a short story than when the examiner elicited the story with a prompt.

It is important to note that children’s narrative skills may differ across narrative genres. In a developmental study of children’s fictional versus personal narratives, C. Peterson and McCabe (1983) found that children produced more goal-directed episodes in their personal compared to fictional narratives across different age groups. Allen, Kertoy, Sherblom, and Pettit (1994) observed that children produced more action sequences and multiple-episode structures in fictional stories, with more reactive sequences and complete episodes during personal event narratives. Looking at children with language impairment, McCabe, Bliss, Barra, and Bennett (2008) noted that the quality of children’s fictional narratives was minimally related to the quality of their personal narratives. Consequently, extant research has revealed a dynamic relationship between context/genre and children’s narration.

Current Practice

Narratives as text is the style that is highly valued in mainstream school culture (Bloome et al., 2003). As a result, the predominant style currently targeted in language assessment and intervention is narrative as text, which is frequently elicited with fictional storybook narratives. One rationale for this predominance is academic. School is an environment that emphasizes decontextualized discourse (Gillam, Peña, & Miller, 1999; Greenhalgh & Strong, 2001). Given that narration involves more distancing and generalization from reality than in-time conversation, narration is a task that taps decontextualized discourse (Kaderavek, Gillam, Ukrainetz, Justice, & Eisenberg, 2004). Skilled narrators integrate their knowledge of the world, narrative structure, and conventional lexical and grammatical markers—also known as literate language—all while evaluating their audience and the social and cultural context (Fang, 2001; Kaderavek et al., 2004). Children who begin school with poor narrative skills relative to these goals more often fail to make the critical connections between spoken language and literacy (Gillam & Johnston, 1992; Gillam et al., 1999; McCabe, 1997; Snow, 1991). Consequently, narratives as text serve as a predictive tool for academic outcomes.

The importance of narrative language skills has driven efforts toward a systematic evaluation and quantification of narrative measures for both mainstream and CLD children (Justice, Bowles, Pence, & Gosse, 2010; J. Miller et. al., 2006; D. Peterson, Gillam, & Gillam, 2008). The elicitation of narratives as text in the context of pictures or picture books often provides for such systematic evaluation and quantification. Current best practice in narrative assessment recommends analysis of narrative macrostructure and microstructure, which are often areas of difficulty for children with language impairment and learning disability (Gillam et al., 1995; Hansen, 1978; Owens, 1999; Roth & Spekman, 1986).

Clinical interpretation

Culture is embedded not only in the narrator’s production of stories, but also in the listener’s interpretation of stories (Minami, 2000), with the potential to affect clinical decision making. Perez and Tager-Flusberg (1998) studied how clinicians judged the oral narrative skills of African American, Latino American, and European American children. They found that despite the clinician’s ethnicity, Latino children, and to some extent African American children, were penalized for using a narrative structure that was different from the European American structure. Clinicians trained in the United States appeared to adopt a European American standard for comparing narrative style. Thus, clinicians may misinterpret or underrate stories that do not conform to the norms of mainstream culture (Bliss & McCabe, 2008; Heath, 1982; McGregor, 2000).

Although several studies have examined the narrative macrostructure and microstructure of children from CLD backgrounds based on wordless picture books, the potential influence of culture on children’s storybook narrative production, including how children make these stories engaging, has not yet been investigated. There is need, however, for such investigation, for as Gutiérrez-Clellen and Quinn (1993) stated, “Knowledge of the influence of both contextual and cultural factors on the production of narratives will allow clinicians to distinguish narrative differences from impaired narrative skills” (p. 2).

PURPOSE

Research to date indicates that there is a dynamic interaction between culture, context/genre, and children’s narration. Prior research has documented numerous cultural differences, predominately in the context of personal stories. In clinical practice, wordless picture books have become a predominant context for narrative language assessment and intervention due to academic expectations and beliefs that this structured context reduces cultural bias inherent in many other tasks.

The purpose of this study was to examine the narratives of African American, Latino, and Caucasian children to analyze the effects of culture and genre on the content and structural organization of narratives based on wordless storybooks. In appreciation of the rich experiences and ideas that children bring to this task, we refer to these two categories of analysis as creative and stylistic devices. Such cross-cultural research will enhance clinicians’ understanding of diversity in discourse styles, which will promote more effective assessment and culturally relevant intervention practices.

METHOD

Participants

Language samples were drawn from a database containing language samples of children who had participated in a dynamic assessment study in which narratives were elicited before and after mediated learning (Peña et al., 2006). Of the 96 African American, Latino, and Caucasian children from working-class families who participated in the initial study, 60 were included in this analysis. For the current analysis, pretest samples were drawn from children who were English-speaking, typical language learners. Participants were then matched by ethnicity, sex, and age, resulting in 20 children, 10 boys and 10 girls, in each ethnic group. Participants had a mean age of 91.9 months (80–101 month range) and were attending first- and second-grade classrooms in Central Texas (see Table 1). Differences in age between ethnic groups were not significant, F(2, 57) =.094, p = .910, .

Table 1.

Ethnicity, sex, and age (in months) of study participants.

| African American | Latino | Caucasian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total # participants | 20 | 20 | 20 | |||

| 1st graders | 12 | 7 | 7 | |||

| 2nd graders | 8 | 13 | 13 | |||

| Age range | 80–95 | 85–100 | 83–101 | |||

| Mean age | 91.95 | 91.6 | 92.25 | |||

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| 1st graders | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 2nd graders | 2 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Age range | 85–98 | 80–98 | 85–97 | 87–100 | 85–95 | 83–101 |

| Mean age | 91.7 | 92.2 | 91.1 | 92.1 | 91.2 | 93.3 |

Children’s language status was evaluated using several measures, including classroom observation of peer interaction (Patterson & Gillam, 1995), teacher report and/or parent report (Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, 2003), and performance on the Test of Language Development—Primary, 3rd Edition (TOLD–P:3; Newcomer & Hammill, 1997) or the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL; Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999). Children were classified as normal language learners if they met at least three of the following conditions: (a) school reports indicated no history of speech or language impairment; (b) teachers and/or parents expressed no concerns with language expression or comprehension; (c) speech-language pathologists expressed no concerns with language expression, comprehension, or peer interaction following classroom observation; or (d) performance within 1 SD from the mean on the TOLD–P:3 or the CASL. Peña et al. (2006) detailed the specific teacher and parent reports and observations of classroom interaction used in the larger study. Note that the speech-language pathologists who completed the classroom observations were not those who collected the baseline language samples.

Procedure

Our analysis focused on the stories that were collected before mediated learning. Wordless picture books were used to elicit fictional narratives. Clinicians presented each participant with one of two wordless picture books, Bird and His Ring or Two Friends (L. Miller, 2000a, 2000b), which were designed to be culturally nonbiased and balanced for the number of pictures, events, characters, and episodes. The two books are centered on a basic search theme and are 12 pages in length. The basic premise of each is that a main character loses something that is important to him; they make attempts to find the object (Bird) or person (Friends); and they finally find what they are looking for. Abstract color drawings represent the characters, place, and time. Validity studies indicate that children’s narratives based on these books yield comparable scores for story elements and story productivity (Peña et al., 2006). In the present study, children first looked at all of the pictures in the book and then generated a story about the book while looking at the pictures a second time. Stories were audio-recorded using a Marantz audio recorder and were later transcribed using Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; J. Miller & Chapman, 2002; J. Miller & Iglesias, 2005) software.

Coding and Analysis

The purpose of the narrative analysis was to identify creative and stylistic conventions children employ when narrating stories based on wordless picture books. Storybook narratives were analyzed for organizational style, and each utterance was analyzed to identify creative features that have been documented in previous studies of children’s personal and fictional stories. In addition, these stories were analyzed to explore whether any additional stylistic features could be identified (e.g., story conclusions, paralinguistic devices, references to conflict). Ultimately, the creative features clustered into four categories: use of dialogue, reference to character relationships, embellishment, and use of paralinguistic devices.

Organizational style

As discussed previously, numerous researchers have documented culturally influenced organizational styles in children’s personal and fictional stories. Wordless picture books are often used in the language assessment protocol to elicit the production of a TC narrative. To investigate the degree to which the storybook narrative context accomplished this goal with children from three ethnic backgrounds, stories were first coded as TC if they met four criteria based on Michaels’ (1981) classification system: (a) They had a clear beginning, middle, and end; (b) they focused on a single topic or closely related topics; (c) there were explicit referential, temporal, and spatial relationships; and (d) there were no major shifts in focus. If a story did not meet these criteria, it was classified as non-topic centered (Non-TC). Non-TC stories often consisted of descriptions of the illustrations.

During the coding process, the authors observed the emergence of two different types of conclusions. Consequently, a second organizational analysis focusing on the story conclusion was performed to explore if such story endings were influenced by ethnicity. Many children’s stories concluded following the linear sequence of beginning, middle, and end, as is generally anticipated in TC stories. Such stories were coded as linear (L). Many other children concluded their stories by bringing the story full circle, with a direct reference to how the story began. These stories were coded as cyclical (Cyc). If a story conclusion did not follow an L or Cyc structure, it was coded as neither (N). With the two categories for coding body and conclusion, many stories received two codes (e.g., TC-L, TC-Cyc). By definition, no stories that were coded as Non-TC could be classified as L. Cyc conclusions were observed in both TC and Non-TC stories.

Creative features

For the remaining analyses, utterances were coded for the number of times the following creative and stylistic features from the following four categories were evident: dialogue, character relationships, embellishment, and paralinguistic devices. Utterances could include multiple instances of the same feature and/or more than one feature in each category. To avoid inflation, utterances and ideas that children repeated were coded as repetitions. A description of each device is as follows.

Dialogue

Direct dialogue. The child puts him- or herself in the character’s role to quote a character in the story. For example, the child says, “Look, I found a ring” or frames the quotation as “The bird said, ‘Look, I found a ring.’”

Indirect dialogue. The child indicates character dialogue with verbs such as talk, say, tell, and ask. For example, “He asked the dragon if he had seen his friend.”

Relationships

Nature of a relationship. The child indicates how characters are related or acquainted using words such as mother, baby, and friend.

Character naming. In both Bird and His Ring (L. Miller, 2000a) and Two Friends (L. Miller, 2000b), all characters resemble animals rather than people, yet the child may invent specific names for the characters, such as Miranda and Sam.

Conduct in relationships. The child refers to ways of behaving or treating others appropriately in relationships, using words such as help, apologize, and polite.

Embellishment

Fantasy. The child creates interest by transcending what is evident in the pictures with original ideas. For example, “He was dreaming about soccer balls and the planets and stuff.”

Suspense. The child creates ambiguity by intentionally leaving out information, asking a question, or hinting at something the listener does not know. For example, “And all of the sudden the cat was gone.” “Where could the cat be?” “Then the hungry tiger started following the dog” (the tone suggestive of an imminent attack on the dog to satisfy the tiger’s hunger).

Conflict. The child captures listener interest by creating conflict in which characters create problems, such as being mean, stealing, and pushing.

Paralinguistic devices

Expressive sounds. The child produces nonword sounds or sound effects such as “wooosh” and “zzzzzzz.”

Exclamatory utterances. The child produces an emphatic sentence or interjection using high volume such as “There it is!” and “Watch out!”

Reliability

Seventy-five percent of the original transcriptions were verified by a second transcriber against the original audio recordings, achieving 95% transcription agreement. Initial coding was completed by the first author. To obtain intercoder reliability for language and stylistic features, 20% of narrative samples, four in each ethnic group, were randomly selected and were coded by a second coder, the fourth author. Interrater agreement was 100% for organizational style and 94% for total creative features. Specifically, agreement was 100% for direct dialogue, 96% for indirect dialogue, 91% for nature of a relationship, 100% for character naming, 89% for conduct in relationships, 90% for fantasy, 90% for suspense, 86% for conflict, 100% for expressive sounds, and 100% for exclamatory utterances. An example of a coded transcript is provided in the Appendix.

Because our study sample was drawn from a larger study, to obtain an equal number of age-matched boys and girls in each ethnic group required unequal numbers of children who narrated Bird and His Ring (BR, n = 15) or Two Friends (TF, n = 45) in each group (African American BR = 7, TF = 13; Latino BR = 3, TF =17; Caucasian BR = 5, TF = 15). Thus, we compared broad measures of productivity, including the number of utterances and total number of words, to ensure that the two books yielded comparable results. These analyses indicated that the two books yielded comparable language productivity, consistent with findings in the larger sample (see Peña et al., 2006). For the stories in the current analysis, children who narrated Bird and His Ring produced a mean of 19.0 utterances per story (SD = 7.13) and a mean of 145.93 words per story (SD = 70.47). Children who narrated Two Friends produced a mean of 18.78 utterances (SD = 6.32) and 119.31 words (SD = 49.74). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the number of utterances across stories was not significant, F(1, 58) = .013, p = .909, . An ANOVA comparing the total number of words across stories also was not significant, F(1, 58) = 2.57, p = .115, , indicating negligible differences.

Next, we wanted to determine if there were group differences in language productivity that could affect each group’s opportunities to use the features studied. The mean number of utterances produced per story by the African American children was 20.15 (SD = 7.03), Latino M = 19.2 (SD = 7.74), and Caucasian M = 17.15 (SD = 4.0). The mean number of words used per story by the African American children was 137.15 (SD = 67.15), Latino M = 121.40 (SD = 56.41), and Caucasian M = 119.35 (SD = 44.88). A one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to determine the effect of ethnicity (African American, Latino, Caucasian) on the two dependent variables, the total number of utterances, and the total number of words. No significant differences in productivity between groups were found, Wilks’s ˄ = .916, F(4, 112) = 1.25, p = .294, .

Statistical Design

To evaluate whether there were significant Organization × Ethnicity effects, Pearson chi-square (χ2) analyses were conducted, and Cramér’s V was used to determine the strengths of association. To determine whether there were significant Creative Feature × Ethnicity effects, a one-way multivariate analysis of variance using number of words as a covariate (MANCOVA) was conducted for each category (i.e., dialogue, character relationships, embellishment, and paralinguistic devices). Follow-up tests were conducted using analyses of variance with the number of words used as a covariate (ANCOVA). Finally, follow-up pairwise comparisons were conducted using the least significant difference (LSD) procedure, which, according to Green and Salkind (2007), is a powerful method to control for Type I errors when a factor has three levels.

RESULTS

The goal of this study was to investigate how culture influences children’s use of creative and stylistic features when narrating wordless picture books. Based on previous research, we focused on organizational style and creativity involving the use of dialogue, reference to character relationships, embellishment, and use of paralinguistic devices to enhance narrative performance and listener engagement. Numerous similarities and differences between groups were found on these features.

Organizational Style

Recall that TC narratives are those that have a tight structure centered on a single topic or closely related topics, with a clear beginning, middle, and end. In our study, all stories were coded as TC or Non-TC. Results are shown in Table 2. The relationship between organization and ethnicity was not significant, Pearson χ2(2, N = 60) = 9.60, p = .619, Cramér’s V = .126. All three groups of children produced predominately TC narratives, with 65% of African American, 60% of Latino, and 50% of Caucasian children using this style.

Table 2.

Organizational style by ethnicity.

| African American | Latino | Caucasian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Story organization | |||

| Topic centered | |||

| Count | 13 | 12 | 10 |

| % within ethnic | 65.0 | 60.0 | 50.0 |

| % within organization | 37.1 | 34.3 | 28.6 |

| % of total | 21.7 | 20.0 | 16.7 |

| Non-topic centered | |||

| Count | 7 | 8 | 10 |

| % within ethnic | 35.0 | 40.0 | 50.0 |

| % within organization | 28.0 | 32.0 | 40.0 |

| % of total | 11.7 | 13.3 | 16.7 |

| Story conclusion | |||

| Linear | |||

| Count | 9 | 8 | 7 |

| % within ethnic | 45.0 | 40.0 | 35.0 |

| % within conclusion | 37.5 | 33.3 | 29.2 |

| % of total | 15.0 | 13.3 | 11.7 |

| Cyclical | |||

| Count | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| % within ethnic | 20.0 | 35.0 | 25.0 |

| % within conclusion | 25.0 | 43.8 | 31.3 |

| % of total | 6.7 | 11.7 | 8.3 |

| Neither | |||

| Count | 7 | 5 | 8 |

| % within ethnic | 35.0 | 25.0 | 40.0 |

| % within conclusion | 35.0 | 25.0 | 40.0 |

| % of total | 11.7 | 8.3 | 13.3 |

Because we wanted to probe the manner in which children concluded their stories, a second analysis for L or Cyc structure was conducted. Recall that L narratives concluded following the linear sequence of beginning, middle, and end, and Cyc narratives concluded with a direct reference to how the story began. In our study, stories were coded as L, Cyc, or N (see Table 3 for descriptive results). Story conclusion and ethnicity were not significantly related, Pearson χ2(4, N = 60) = 1.83, p = .768, Cramér’s V = .12. All three groups of children produced predominately L narratives, with 45% of African American, 40% of Latino, and 35% of Caucasian children using this style. Twenty percent of African American, 35% percent of Latino, and 25% of Caucasian children produced Cyc narratives. Overall, although many children did not produce TC stories, these results suggest that storybook narratives provide a culturally nonbiased context for analyzing children’s ability to produce sequentially organized narratives as text.

Table 3.

Creative features by ethnicity.

|

African American

|

Latino

|

Caucasian

|

F | p |

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||||

| Dialogue | 2.51 | .046* | .08 | |||||||

| Direct | 4.70 | 5.83 | 2.45 | 3.73 | 1.10 | 1.59 | 3.49 | .037* | .11 | |

| Indirect | 1.85 | 1.69 | 3.10 | 2.17 | 2.65 | 2.46 | 1.85 | .167 | .06 | |

| Character relationships | 3.02 | .019* | .14 | |||||||

| Nature | .95 | 1.88 | .50 | .69 | 2.05 | 2.50 | 3.93 | .025* | .12 | |

| Naming | .05 | .22 | 1.85 | 4.74 | .00 | 3.58 | .035* | .11 | ||

| Conduct | .25 | .72 | .35 | .88 | .25 | .55 | .20 | .817 | .01 | |

| Embellishment | 2.59 | .022* | .13 | |||||||

| Fantasy | 1.25 | 1.41 | .10 | .31 | .75 | 1.00 | 5.93 | .005* | .18 | |

| Suspense | 1.30 | 1.03 | .70 | .92 | .70 | .87 | 2.34 | .106 | .08 | |

| Conflict | .40 | .75 | .35 | .81 | .35 | .59 | .00 | 1.000 | .00 | |

| Paralinguistic devices | 1.47 | .216 | .05 | |||||||

| Expressive | .70 | 2.16 | .45 | 1.19 | .00 | |||||

| Exclamation | .45 | .69 | .25 | .64 | .05 | .22 | ||||

Statistical significance at the p < .05 level.

Creative Features

For the remaining analyses, utterances were coded for the number of times the following creative and stylistic features from the following four categories were evident: dialogue, character relationships, embellishment, and paralinguistic devices. Utterances could include multiple instances of the same feature and/or more than one feature in each category. Table 3 contains the means and standard deviations of the dependent variables for each ethnic group.

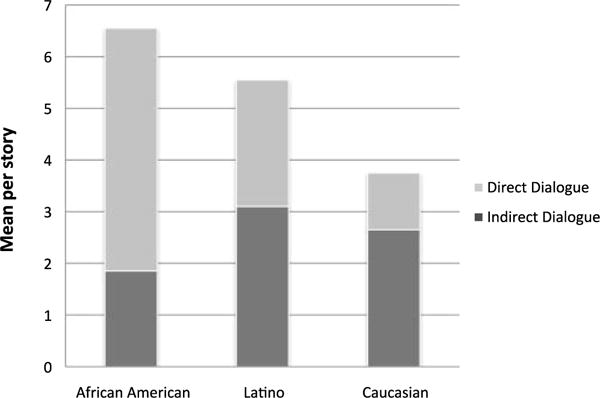

Dialogue

A MANCOVA revealed a statistically significant Dialogue × Ethnicity effect, Wilks’s ˄ = .84, F(4, 110) = 2.51, p = .046, . A follow-up ANCOVA indicated a significant difference between groups on the use of direct dialogue, F(2, 56) = 3.49, p = .037, , but not indirect dialogue, F(2, 56) = 1.85, p = .167, . Pairwise comparisons indicated that the African American children used significantly more direct dialogue than the Caucasian children (p = .011). African American and Latino children demonstrated comparable use of direct dialogue (p = .145), as did Latino and Caucasian children (p = .246). Figure 1 displays average dialogue use by ethnic group.

Figure 1.

Dialogue use by ethnicity.

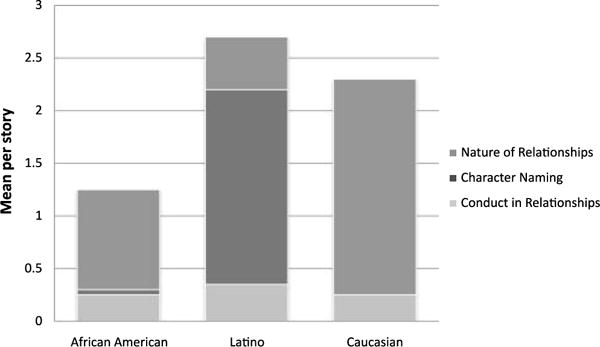

Character relationships

A MANCOVA indicated a significant difference among ethnic groups in children’s reference to character relationships, Wilks’s ˄ = .73, F(6, 108) = 3.02, p = .019, . Follow-up ANOVAs indicated statistically significant differences between groups for reference to the nature of relationships, F(2, 56) = 3.93, p = .025, , and the use of character naming, F(2, 56) = 3.58, p = .035, . The ANCOVA on conduct in relationships was not significant, F(2, 56) = .20, p = .817, . Pairwise comparisons indicated that the Caucasian children referred to the nature of relationships significantly more than did the African American (p = .046) and Latino (p = .010) children. African American and Latino children produced comparable references to the nature of relationships (p = .535). Latino children named their characters more often than both African American (p = .019) and Caucasian children (p = .033). There were no significant differences in character naming between African American and Caucasian children (p = .804). Figure 2 depicts reference to character relationships by ethnic group.

Figure 2.

Character relationships by ethnicity.

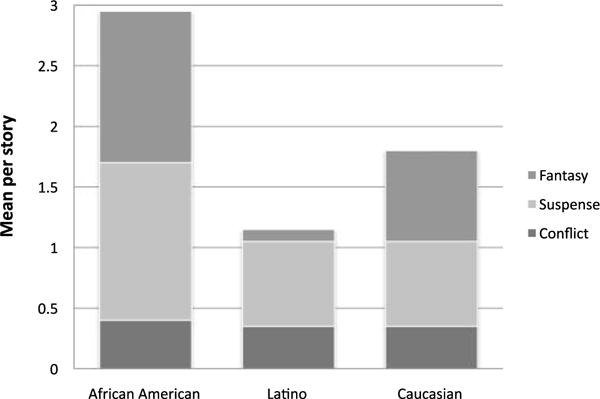

Embellishment

A MANCOVA revealed a significant Embellishment × Ethnicity effect, Wilks’s ˄ = .76, F(6, 108) = 2.59, p = .022, . ANCOVAs indicated significant differences between groups for the use of fantasy F(2, 56) = 5.94, p = .005, . The ANCOVAs on suspense, F(2, 56) = 2.34, p = .106, , and conflict, F(2, 56) = .00, p = 1.00, , were not significant. Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that African American and Caucasian children incorporated significantly more fantasy in their stories than did Latino children (p = .047 and p = .001, respectively). African American and Caucasian children’s use of fantasy was comparable (p = .166). See Figure 3 for a display of embellishment usage by ethnic group.

Figure 3.

Embellishment by ethnicity.

Paralinguistic devices

African American and Latino children occasionally used expressive sounds to enhance their stories, whereas Caucasian children did not. All groups occasionally used exclamatory utterances. A MANCOVA indicated that differences between groups were not statistically significant, Wilks’s ˄ = .90, F(4, 110) = 1.47, p = .216, .

DISCUSSION

The focus of this study was to explore children’s use of culturally infused creative and stylistic features in their storybook narratives. Overall, although the children from the three ethnic groups in this sample used a similar organizational style, there was evidence of culturally based influences on the creative features they employed, which reflected an integration of both individualistic and collectivistic perspectives in children’s narration during a structured storybook narrative task.

Organizational Style

TC stories represented the most commonly used organizational style in all three ethnic groups. This finding supports the appropriateness of storybook narration as a culturally less-biased language assessment task for early elementary-age children (Craig, Washington, & Thompson-Porter, 1998; L. Miller et al., 2001). Whereas earlier research indicated cultural differences in narrative organization, including the use of topic association by some African American children and greater description than event sequencing by some Latino children (e.g., Michaels, 1981; Rodino et al., 1991; Silva & McCabe, 1996), all ethnic groups in our study produced predominately TC-L stories. Therefore, in contrast with other studies, group differences in story organization according to Hofstede’s (1986, 2001) individualism–collectivism framework were not apparent in our study. One explanation for the divergence of our results from those documented by past research may involve the role of schooling in shaping narrative style. Current first-grade curriculum guidelines include engaging children in comparing and predicting events in stories as well as developing an understanding of story characters (Burns, Griffin, & Snow, 1999). Consequently, it is possible that a trend toward increased intentionality in teaching narrative structure may have contributed to the predominance of TC story organization in the current study. Recall that in our sample, 50% to 65% of children across ethnic groups produced TC narratives, a finding that contributes to the literature on narrative organization of children from various ethnic backgrounds and also to our understanding of narratives as text style development of first and second graders in general.

Another compelling explanation for our findings lies in the nature of the narrative genre and elicitation method we used. Numerous researchers have indicated that both genre and prompt impact children’s story production; therefore, the influence of culture on narrative performance may also depend on the genre and prompt (e.g., Champion, 1998, 2003; Champion et al., 1995; Horton-Ikard, 2009; Katz & Champion, 2009; Mainess, Champion, & McCabe, 2002). Personal narratives are less subject to organizational constraints than storybook narratives. Therefore, one would expect that elicitation using a wordless picture book depicting a predetermined chronological sequence would minimize variability in structural organization. Our data indicating that more than half of the children in our sample produced TC stories support this idea. It is interesting to compare our findings with those of Hyon and Sulzby (1994), who analyzed the stories of African American kindergartners during a personal narrative task unconstrained by visual cues. They found that 58% of the children sampled produced TC personal narratives. Coincidentally, this percentage is equivalent to the percentage (58%) of the slightly older first- and second-grade children in our sample who produced TC stories during the structured narrative task. Given the contextual constraints on story organization in our narrative task, one might have expected that a higher percentage of children in our sample than in Hyon and Sulzby’s sample would have produced TC stories. Another sample of children with different experiential and educational backgrounds may yield different results.

Although there were no significant differences between groups in children’s story conclusions, it was noted that many children produced what we called a Cyc narrative, in which their story ending included a direct reference to how the story began. To our knowledge, this type of story conclusion has not been reported in the literature. Bidell, Hubbard, and Weaver (1997) previously used the term “cyclical” to refer to multiple cycles of repetition within the narrative, a technique they observed elementary-age African American children use to engage the audience and amplify the story before its culmination. In contrast, we noted only one cycle that served to conclude the story rather than to amplify or elaborate on the theme, reminiscent of the manner in which some well-known storybooks conclude, such as If You Give a Mouse a Cookie (Numeroff, 1985) and If You Give a Pig a Pancake (Numeroff, 1998). In fact, given that Cyc structure is not directly taught, this phenomenon may be attributed to children’s familiarity with and internalization of this pattern in such stories.

Creative Features

Although the majority of children produced TC-L stories as consistent with mainstream school expectations, there were differences by ethnicity in the children’s use of creative features. We propose that the differential use of creative features is reflective of children’s home cultures and sociocultural expectations. Specifically, differences were seen in the areas of dialogue, relationships, and embellishment.

With respect to analysis of dialogue, differences were observed in direct dialogue but not indirect dialogue. African American children produced the most direct dialogue. These results are intriguing because they underscore an area of narration that clinicians may overlook as an important feature of storytelling. A “good” narrative may be one that not only contains a well-organized representation of events, but also captures the listener’s attention and interest. Bloome et al. (2003) described this difference as narrative as text or narrative as performance. In their evaluation of what makes a good story, Ulatowska et al. (2004) indicated that direct speech serves to engage the listener by making events more immediate and realistic. These features of text as performance are complex in structure and may not be included in a traditional repertoire of narrative evaluation, including evaluative, moral-centered, and performative aspects of narration. However, in a storytelling tradition that heavily emphasizes the relationship between narrator and audience, we might expect a sociocultural contribution to greater usage of direct dialogue in African American children’s narratives. Latino children produced the most indirect dialogue, although results did not reach statistical significance. Through the use of both direct and indirect dialogue, children demonstrate their ability to interpret how the story characters might be relating and communicating with each other.

Analysis of reference to relationships revealed that Caucasian children referred to the nature of relationships significantly more than the other two groups did. The references expressed most frequently were friend, mother, and baby. These results were surprising, as Cristofaro and Tamis-Lemonda (2008) found a tendency for Latino parents to use personal stories as opportunities to teach children about the nature of family relationships. In contrast, Latino children in our study named their characters more than the other groups did. This tendency may be linked to the sociocultural tradition of naming family members in personal narratives to teach children about nuclear and extended family as consistent with a collectivistic world view. Cristofaro and Tamis-Lemonda observed that Latino parents often encouraged their children to recite family members’ names during their personal stories and observed keen interest in their children’s ability to do so. In a narrative context, naming characters in a story provides the listener with a more definite referent, which contributes to story cohesion. The use of character names provides more than a description of actions produced by a generic agent (e.g., “the girl”) and individualizes the characters. Clinicians may anticipate that children who are good storytellers will name characters. In a study of the expressive elaboration of children with and without language impairment, children with typical language were more likely than their peers with language impairment to name characters in a fictional story using picture prompts (Ukrainetz & Gillam, 2009). Results documenting the variability of naming characters across cultures are important because little information currently exists about the sociocultural contribution to children’s structured text-like narratives such as those elicited in the current study.

Analysis of embellishment indicated that African American children included the most fantasy and suspense in their stories compared to the other children. This difference was somewhat unexpected in light of the finding that children from all three groups produced predominantly TC-L narratives. Because TC-L narratives are generally thought to emphasize factual and sequential description of events, one might expect that differences in embellishment between ethnic groups would be minimized. This task, however, did not appear to significantly limit children’s tendency to infuse embellishment into their stories. It is important to note that fantasy and suspense enhance the performative aspect of storytelling, neither of which is currently part of the typical repertoire of quantitative narrative assessment analyses (notable exceptions include Ukrainetz & Gillam, 2009). Because additional features of good stories include their uniqueness and their ability to engage the audience (Bloome et al., 2003; Ulatowska et al., 2004), embellishment merits consideration for qualitative analysis of storybook narratives.

Finally, we found minimal use of paralinguistic devices in children’s stories, and thus, no statistically significant differences between groups. This finding is in contrast to Champion’s (2003) description of personal narratives, in which African American children occasionally used a wide range of paralinguistic devices to engage their audience. In the present study, we attribute this to the effect of genre, such that the structured storybook narratives task may have limited children’s infusion of paralinguistic devices in their stories. This would reaffirm the well-supported notion that storybook narrative tasks tap children’s decontextualized discourse skills. This finding of nonsignificance may also highlight children’s narrative flexibility between genres and audiences (Hester, 1996), reinforcing the dynamic relationship between culture, genre, and narration.

Overall, the contribution of our analysis of stylistic and creative features yields a view of narration that goes beyond the idea of narratives as exact reproductions of what the pictures portray. We examined unique sociocultural contributions that impact children’s interpretation of the how and why of storytelling. Additionally, by including new lenses on what we examined in children’s narratives, we were able to view particular sociocultural strengths in an academic task that is traditionally examined with an eye on episodic and chronological structure as the standard (Uccelli, 2008). This analysis uncovered unique sociocultural patterns on an academic task where children may be learning a new standard of storytelling involving school peers and teacher as both model and audience.

Clinical Implications

According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2010), culturally competent service delivery includes the ability to recognize cultural differences in narrative style and to plan culturally relevant intervention. As such, results from this study have implications for both narrative assessment and intervention for children from diverse backgrounds. Recently, Ukrainetz and Gillam (2009) found less expressive elaboration of 6- to 8-year-old children with specific language impairment when narrating stories elicited using the Test of Narrative Language (TNL; Gillam & Pearson, 2004). Among other expressive elaborations examined, children used fewer character names and relations, repetitions for emphasis, orientations, and dialogue. Clinicians may be beginning to look beyond traditional narrative structures using stories elicited to help diagnose children with impairment.

Clinicians should be aware that their interpretations may be biased toward their own preference for what constitutes a good narrative, in part, perhaps, because current literature focuses almost exclusively on the story structure over the performative aspects of storytelling. Therefore, an enhanced understanding of the potential sociocultural influences on children’s use of stylistic and creative features in their narratives is integral to both nonbiased interpretation and identification of children’s strengths in narrative performance and stylistic flexibility across discourse genres.

When planning ecologically valid narrative intervention, clinicians should keep in mind that narratives serve many functions, including to inform and to entertain. Clinicians should be able to foster narrative skills as valued by children’s culture (Bliss, McCabe, & Mahecha, 2001). Because effective intervention promotes academic and social functioning, clinicians should consider targeting children’s effective delivery of narratives as text to promote academic achievement and narratives as performance to promote social development.

We conclude with a critical caveat: Although research illuminates some cultural differences, it is critical that clinicians also acknowledge that significant individual differences exist within cultural groups. As Uccelli (2008) stated:

On the one hand, broad guidelines for understanding the narrative development of children from different cultural/linguistic backgrounds are extremely helpful. On the other hand, it is necessary to remember that each child is unique and reflects diverse experiences not always easily classifiable as those of one discrete cultural group. (p. 203)

Consequently, alternative models for assessment and intervention such as the one we have presented should serve as options based on careful consideration of each client as a unique individual.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant K23 DC00141 awarded to the third author. We also give our sincerest thanks to Ronald B. Gillam for his valuable input.

APPENDIX. SAMPLES OF NARRATIVE CODING

| Child 1 |

| C Once there lived a bird who saw a ring on a cactus. |

| C He took it off there and carried it home. |

| C He saw a bird on the way. |

| C The bird asked him if he could have the ring [ID]. |

| C So he said, “Yes, very well” [D]. |

| C And he walked back home thinking of it. |

| C Soon he came back to ask the bird for his ring back [ID]. |

| C The bird said “No” [D]. |

| C But he took it anyways [Con]. |

| C And then the bird started to cry. |

| C So he let him have it [RC]. |

| C But he went back home and told his friends about the ring [ID][RN]. |

| C He told his friend the rooster [ID][RN]. |

| C And he told his friend the lizard [ID][RN]. |

| C He told his friend the ostrich while his friend the lizard was beside him [ID][RN][RN]. |

| C So him and his friend the lizard walked back to the bird’s nest [RN]. |

| C Then they saw the ring lying below the tree. |

| C And then the bird went to ask a little bird if he could have the ring [ID]. |

| C And the bird said “Sure” [D]. |

| C And he said “Thank you” [D][RC]. |

| C The End [TC][L]. |

| Child 2 |

| C One day dragon and bird were playing outside. |

| C And dragon saw bird’s ring. |

| C One day dragon caught the ring when bird was asleep. |

| C He brung it to mama bird [RN]. |

| C Mama bird said, “Where did you find the ring” [D][RN]? |

| C That morning mama bird said, “Have you ever stolen a ring like this of bird’s” [D][RN][Con]? |

| C Lizard and dragon said to bird, “I am sorry that I stole your ring” [D][RC][Con]. |

| C And one day mama bird gave up the ring [RN]. |

| C She flew out and brung bird the ring. |

| C “I am so sorry that dragon stole your ring” [D][RC][Con]. |

| C They caught mama bird without any ring [RN]. |

| C Lizard said, “So where is the ring” [D][Sus]? |

| C Dragon said, “Where is it” [D][Sus]? |

| C And then dragon ran along. |

| C One day dragon ask water hose, “Where did you get the ring” [D][Fan]? |

| C And he told him in front of bird that “I stole the ring from bird” [D][Con]. |

| C Bird heard him. |

| C One day they passed by. |

| C Baby bird said, “How come you stole it” [D][RN][Con]? |

| C “That’s not polite” [D][RC]. |

| C “You are mean [D][Con]. |

| C “Hey there is somewhere we can go” [D][Sus][Exc]! |

| C And lizard asked, “Would you go get the ring” [D]? |

| C “And we will steal it from bird again” [D][Con][Exc]! |

| C And one day it was lying by mama’s bird nest [RN]. |

| C “We found the ring mama bird” [D][RN]. |

| C “I threw it out because that’s not polite” [D][RC]. |

| C One winter night it was a stormy month. |

| C The end [Non-TC][N]. |

Note. C = child utterance, [D] = direct dialogue, [ID] = indirect dialogue, [RN] = nature of a relationship, [N] = naming, [RC] = conduct in relationships, [F] = fantasy, [Sus] = suspense, [Con] = conflict, [Exp] = expressive sounds, [Exc] = exclamatory utterance, [TC] = topic centered, [Non-TC] = non-topic centered, [L] = linear, [N] = neither.

References

- Allen MS, Kertoy MK, Sherblom JC, Pettit JM. Children’s narrative productions: A comparison of personal event and fictional stories. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1994;15:149–176. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Cultural competence checklist: Service delivery. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/practice/multicultural/self.htm.

- Bauman R, Briggs C. Poetics and performance as critical perspectives on language and social life. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1990;19:59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman R, Sherzer J. The ethnography of speaking. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1975;4:95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Berman RA, Slobin DI. Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidell TR, Hubbard LJ, Weaver M. Story structure in a sample of African-American children: Evidence for a cyclical story schema. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Washington, DC. 1997. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Bliss LS, McCabe A. Personal narratives: Cultural differences and clinical implications. Topics in Language Disorders. 2008;28:162–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss LS, McCabe A, Mahecha NR. Analyses of narratives from Spanish-speaking children. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders. 2001;28:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bloome D, Katz L, Champion T. Young children’s narratives and ideologies of language in classrooms. Reading & Writing Quarterly. 2003;19:205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Burns MS, Griffin P, Snow CE, editors. Starting out right: A guide to promoting children’s reading success. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Carrow-Woolfolk E. Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language. Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Celinska DK. Narrative voices of early adolescents: Influences of learning disability and cultural background. International Journal of Special Education. 2009;24:150–172. [Google Scholar]

- Champion TB. “Tell me somethin’ good”: A description of narrative structures among African American children. Linguistics and Education. 1998;9:251–286. [Google Scholar]

- Champion TB. Understanding storytelling among African-American children: A journey from Africa to America. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Champion TB, Seymour H, Camarata S. Narrative discourse of African American children. Journal of Narrative and Life History. 1995;5:333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Cortazzi M. Narrative analysis. London, England: Falmer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Craig HK, Washington JA, Thompson-Porter C. Average C-unit lengths in the discourse of African American children from low-income, urban homes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1998;41:433–444. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4102.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofaro TN, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Lessons in mother–child and father–child personal narratives in Latino families. In: McCabe A, Bailey AL, Melzi G, editors. Spanish-language narration and literacy: Culture, cognition and emotion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 54–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z. The development of schooled narrative competence among second graders. Reading Psychology. 2001;22:205–223. [Google Scholar]

- Feagans L, Appelbaum M. Validation of language subtypes in learning disabled children. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1986;78:358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Finestack LH, Fey ME, Sokol SB, Ambrose S, Swanson LA. Fostering narrative and grammatical skills with “syntax stories”. In: van Kleeck A, editor. Sharing books and stories to promote language and literacy. San Diego, CA: Plural; 2006. pp. 319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Gillam RB, Johnston JR. Spoken and written language relationships in language/learning-impaired and normally achieving school-age children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:1303–1315. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3506.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam RB, McFadden TU, van Kleeck A. Improving narrative abilities: Whole language and language skills approaches. In: Fey ME, Windsor J, editors. Language intervention: Preschool through the elementary years. Vol. 5. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1995. pp. 145–182. (Communication and language intervention series). [Google Scholar]

- Gillam RB, Pearson NA. Test of Narrative Language. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gillam RB, Peña ED, Miller L. Dynamic assessment of narrative and expository discourse. Topics in Language Disorders. 1999;20(1):33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Green SB, Salkind NJ. Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and understanding data. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM, Quiroz B, Raeff C. Cross-cultural conflict and harmony in the social construction of the child. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2000;87:93–108. doi: 10.1002/cd.23220008708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh KS, Strong CJ. Literate language features in spoken narratives of children with typical language and children with language impairments. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2001;32:114–125. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2001/010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, Heinrichs-Ramos L. Referential cohesion in the narratives of Spanish-speaking children: A developmental study. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:559–567. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3603.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, Kreiter J. Understanding child bilingual acquisition using parent and teacher reports. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24(2):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, Quinn R. Assessing narratives in diverse cultural/linguistic populations: Clinical implications. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1993;24(1):2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Haden CA, Haine RA, Fivush R. Developing narrative structure in parent–child reminiscing across preschool years. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:295–307. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen C. Story retelling used with average and learning disabled readers as a measure of reading comprehension. Learning Disability Quarterly. 1978;1:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward D, Schneider P. Effectiveness of teaching story grammar knowledge to pre-school children with language impairment. An exploratory study. Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 2000;16:255–284. [Google Scholar]

- Heath SB. What no bedtime story means: Narrative skills at home and school. Language in Society. 1982;11(1):49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg NL, Westby CE. Analyzing story skills: Theory to practice. Tucson, AZ: Communication Skills Builders; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hester EJ. Narratives of young African American children. In: Kamhi AG, Pollock KE, Harris JL, editors. Communication development and disorders in African American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1996. pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1986;10:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Horton-Ikard R. Cohesive adequacy in the narrative samples of school-age children who use African American English. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2009;40:393–402. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2009/07-0070). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson J, Shapiro L. From knowing to telling: The development of children’s scripts, stories and personal narratives. In: McCabe A, Peterson C, editors. Developing narrative structure. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 89–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hyon S, Sulzby E. African American kindergartners’ spoken narratives: Topic associating and topic centered styles. Linguistics and Education. 1994;6:121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Justice LM, Bowles RP, Kaderavek JN, Ukrainetz TA, Eisenberg SL, Gillam RB. The index of narrative microstructure: A clinical tool for analyzing school-age children’s narrative performances. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2006;15:155–191. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2006/017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice LM, Bowles R, Pence K, Gosse C. A scalable tool for assessing children’s language abilities within a narrative context: The NAP (Narrative Assessment Protocol) Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25:218–234. [Google Scholar]

- Labov W. Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English vernacular. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kaderavek JN, Gillam RB, Ukrainetz TA, Justice LM, Eisenberg SN. School-age children’s self-assessment of oral narrative production. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2004;26(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L, Champion T. Affirming students’ right to their own language: Bridging language policies and pedagogical practices. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. There’s no “1” way to tell a story; pp. 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Mainess K, Champion T, McCabe A. Telling the unknown story: Complex and explicit narration by African American preadolescents: Preliminary examination of gender and socioeconomic issues. Linguistics and Education. 2002;13(2):151–173. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe A. Chameleon readers: Teaching children to appreciate all kinds of good stories. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe A. Developmental and cross-cultural aspects of children’s narration. In: Bamberg M, editor. Narrative development: Six approaches. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 137–174. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe A, Bliss LS. Narratives from Spanish-speaking children with impaired and typical language development. Imagination, Cognition and Personality. 2004–2005;24(4):331–346. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe A, Bliss L, Barra G, Bennett M. Comparison of personal versus fictional narratives of children with language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2008;17:194–206. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2008/019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor KK. The development and enhancement of narrative skills in a preschool classroom: Towards a solution to clinician–client mismatch. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2000;9:55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Melzi G. Cultural variations in the construction of personal narratives: Central American and European American mothers’ elicitation style. Discourse Processes. 2000;30:153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels S. “Sharing time”: Children’s narrative and differential access to literacy. Language in Society. 1981;10:423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Chapman RS. SALT for Windows (Research Version 7.0) [Computer software] Madison: University of Wisconsin–Madison: Waisman Center, Language Analysis Laboratory; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Iglesias A. Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (Version 9.0) [Computer software] Madison: University of Wisconsin–Madison: Waisman Center, Language Analysis Laboratory; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Iglesias A, Heilman J, Fabiano L, Nockerts A, Francis D. Oral language and reading in bilingual children. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2006;21:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. Bird and his ring. Austin, TX: Neon Rose Productions; 2000a. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. Two friends. ustin, TX: Neon Rose Productions; 2000b. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Gillam RB, Peña ED. Dynamic assessment and intervention: Improving children’s narrative skills. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Minami M. The relationship between narrative identity and culture. Narrative Inquiry. 2000;10(1):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer P, Hammill D. Test of Language Development—Primary. Third. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols P. Storytelling in Carolina: Continuities and contrasts. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 1989;20:232–245. [Google Scholar]

- Numeroff L. If you give a mouse a cookie. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Numeroff L. If you give a pig a pancake. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Owens RE. Language disorders: A functional approach to assessment and intervention. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson S, Gillam RB. Team collaboration in the evaluation of language of students above the primary grades. In: Tibbits D, editor. Language intervention: Beyond the primary grades. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1995. pp. 137–181. [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED, Gillam RB, Malek M, Felter R, Resendiz M, Fiestas C, Sabel T. Dynamic assessment of children from culturally diverse backgrounds: Applications to narrative assessment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:1037–1057. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/074). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C, Tager-Flusberg H. Clinicians’ perceptions of children’s oral personal narratives. Narrative Inquiry. 1998;8(1):181–201. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, McCabe A. Developmental psycholinguistics: Three ways of looking at a child’s narrative. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson D, Gillam SL, Gillam RB. Emerging procedures in narrative assessment: The Index of Narrative Complexity. Topics in Language Disorders. 2008;28:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rodino AM, Gimbert C, Perez C, Craddock-Willis K, McCabe A. Getting your point across: Contractive sequencing in low-income African-American and Latino children’s personal narratives. Paper presented at the 16th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development; Boston, MA. 1991. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. Cultural nature of human development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roth FP, Spekman NJ. Narrative discourse: Spontaneously generated stories of learning-disabled and normally achieving students. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1986;51:8–23. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5101.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MJ, McCabe A. Vignettes of the continuous and family ties: Some Latino American traditions. In: McCabe A, editor. Chameleon readers: Teaching children to appreciate all kinds of good stories. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1996. pp. 116–136. [Google Scholar]

- Snow CE. The theoretical basis for relationships between language and literacy development. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. 1991;6:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LA, Fey ME, Mills CE, Hood LS. Use of narrative-based language intervention by children who have specific language impairment. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2005;14:131–145. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2005/014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli P. Beyond chronicity: Evaluation and temporality in Spanish-speaking children’s personal narratives. In: McCabe A, Bailey AL, Melzi G, editors. Spanish-language narration and literacy: Culture, cognition and emotion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 175–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ukrainetz TA, Gillam RB. The expressive elaboration of imaginative narratives by children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:883–898. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0133). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulatowska HK, Streit-Olness G, Samson AM, Keebler MW, Goins KE. On the nature of personal narratives of high quality. Advances in Speech-Language Pathology. 2004;6:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Leichtman MD. Same beginnings, different stories: A comparison of American and Chinese children’s narratives. Child Development. 2000;71:1329–1346. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westby CE. Development of narrative language abilities. In: Wallach G, Butler K, editors. Language and learning disabilities in school-age children. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 103–127. [Google Scholar]