Abstract

Purpose

Primary lacrimal canaliculitis (PLC) is a unique disorder which often gets misdiagnosed by the general as well as speciality-trained ophthalmologists. Elderly patients with history of chronic or recurrent epiphora with discharge, often get mislead towards chronic dacryocystitis. The aim of our report is to discuss the misleading diseases in our PLC patients and to revisit this hidden disease.

Methods

The patients of PLC who were previously misdiagnosed were studied. The clinical history, presenting clinical features, misdiagnosis, and final management of the patients is described.

Results

There were 5 misdiagnosed female patients. A history of chronic redness, watering, discharge, and medial canthal region edema lead to the misdiagnosis of chronic dacryocystitis in 3 (60%) and medial marginal chalazion in 2 (40%) cases. Slit-lamp examination revealed localized hyperemia (n = 5), classical pouting of lacrimal punctum (n = 3), and expressible purulent discharge (n = 3). Two patients without punctum pouting had an explicit yellowish hue/discoloration of the canalicular region. Our patients had a mean 4 visits before an accurate diagnosis. Three-snip punctoplasty with canalicular curettage was performed in three while two were managed conservatively. At last follow-up, all patients were symptom-free with punctum and canalicular scarring in three, who underwent surgery.

Conclusion

PLC is a frequently misdiagnosed clinical entity which delays the initiation of appropriate treatment. A succinct magnified examination of punctum and canalicular region can provide sufficient clues pivotal for accurate diagnosis.

Keywords: Primary lacrimal canaliculitis, Misdiagnosis, Lacrimal canaliculus, Lacrimal punctum, Chronic dacryocystitis

Introduction

Lacrimal canaliculitis is a suppurative or non-suppurative inflammation of the canalicular tract.1 A gender preponderance for females and location propensity for inferior canaliculus is often observed.1, 2 Etiologically, suppurative or primary lacrimal canaliculitis (PLC) is mainly caused by Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Actinomyces species.2 Secondary lacrimal canaliculitis (SLC) is associated with the usage of punctum-plugs and lacrimal stents. Hence, this specific history helps ophthalmologists reach an early diagnosis of SLC which is most commonly (46%) caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.3, 4

The chief complaints associated with canaliculitis such as watering, intermittent discharge, and pain often mimic those seen in chronic dacryocystitis. Clinically, presence of medial canthal region edema and expressible purulent discharge further increases the chances for its misdiagnosis as chronic dacryocystitis. In literature, this rate of clinical misdiagnosis ranges from 45 to 100%.5, 6 Prominent local features like pouting of punctum, yellowish hue/discoloration of canalicular region and localized hyperemia point specifically towards lacrimal canaliculitis.

In this article, we report five clinically misdiagnosed patients of PLC and highlight its classical clinical features. We aim to discuss the misleading diseases, revisit this occult disease, and create awareness of PLC misdiagnosis amongst practicing general and speciality-trained ophthalmologists.

Case report

Misdiagnosis as chronic dacryocystitis in 3 patients

Three elderly females, hypertensive (n = 3) and diabetic (n = 2), presented with similar chief complaints of unilateral redness, watering, and constant discharge for mean 13 months (range, 9–18 months). They were first misdiagnosed as infective bacterial conjunctivitis and were treated with topical antibiotics for mean 12.67 months. Later, they were diagnosed as primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (PANDO) by three different ophthalmologists and all were advised a dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) surgery.

At presentation, localised medial eyelid edema, local erythema (superficial dilated vessels), mild conjunctival congestion, and expressible whitish granular discharge was seen in all (Fig. 1, Fig. 2a). Classical pouting of punctum and a yellowish hue/discoloration of canalicular region were universal features (Fig. 1a,c). There was neither any swelling nor any ‘regurgitation on pressing lacrimal sac’ region (ROPLaS). The clinical diagnosis of PLC with canalicular concretions was kept in all, and a 3-snip punctoplasty with canalicular curettage was performed under local anaesthesia.7 Multiple inspissated sulphur-like granular concretions were curetted out (Fig. 1d). Azithromycin ointment was injected into canalicular lumen at the end of surgery, as described by Xu et al.8

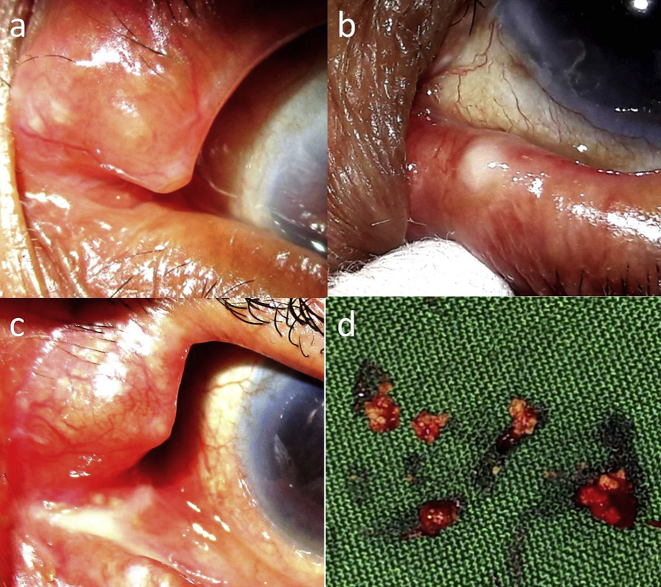

Fig. 1.

Characteristic clinical features of primary lacrimal canaliculitis (PLC): a. Left superior punctum showing characteristic pouting. Prominent local vasculature and yellowish hue/discoloration of canalicular region is distinctively seen. b. The left inferior punctum shows typical whitish granular discharge expressed with a cotton-tip applicator. Punctum pouting and inflamed canalicular region is appreciable. c. Superior inflamed punctum and canalicular region with whitish granular discharge over caruncle. d. Multiple clumps of sulphur-like granular concretions after 3-snip punctoplasty and canalicular curettage.

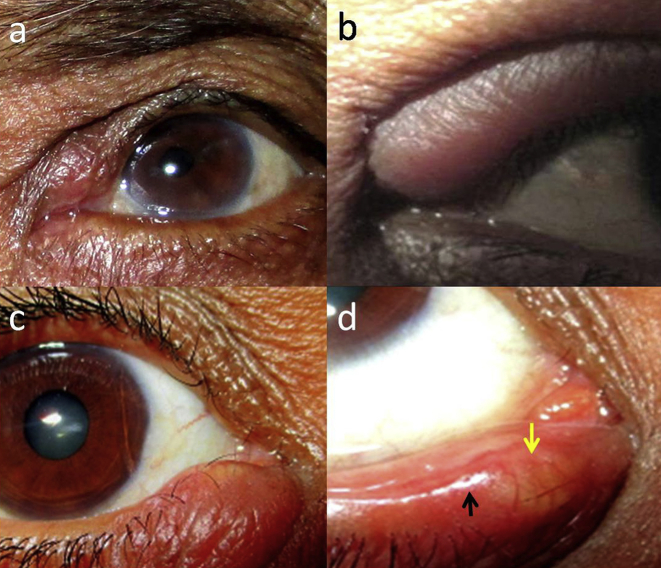

Fig. 2.

Misdiagnosis of primary lacrimal canaliculitis (PLC): a. (Misdiagnosed-chronic dacryocystitis) Left superior inflamed punctum and medial canthal region but the edema is above medial canthal tendon with negative ‘regurgitation on pressing lacrimal sac’ region (ROPLaS). b. (Misdiagnosis – superior medial chalazion) The edema of eyelid extends medially in the non-ciliated or canalicular region of eyelid, making external or internal hordeolum a lower possibility. c. (Misdiagnosis-inferior medial chalazion) The erythema and edema over canalicular region with yellowish hue/discoloration. d. On eyelid eversion, localised erythema and yellowish hue/discoloration (yellow arrow) of canalicular region is seen prominently. The punctum (black arrow) is present laterally and appears stenosed.

Oral azithromycin [500 mg once daily (OD) for 1 week] and fortified cefazolin 5% eye drops [2 hourly for 1 week, followed by four times a day (QID)] was prescribed for 1 month. At mean follow-up of 18 months, all patients were symptom-free but one had an intermittent clear epiphora (Fig. 1d). In all, the functional dye disappearance test (FDDT) & lacrimal irrigation suggested obstructed canaliculi. The microscopy showed Actinomyces Israeli, Staphylococcus aureus and Nocardia asteroids in each specimen.

Misdiagnosis as medial chalazion in 2 patients

Two middle-aged females had history of redness, pain, and intermittent watering from one eye each since 1 year. Both received treatment for bacterial conjunctivitis for mean 6.5 months and were diagnosed as medial chalazion for which an incision and curettage was advised. On presentation to us, both had localised medial eyelid edema and erythema of left upper and right lower eyelid (Fig. 2b,c). On slit-lamp examination, the nodular edema extended medially from the punctum to the canalicular region (Fig. 2d). In both, a yellow hue/discoloration of canalicular region was noticed which is probably due to the presence of sulphur-like granules in canalicular lumen. No localised tenderness, punctum pouting, expressible discharge, or sac swelling was noticed. The ROPLaS was negative.

A conservative management – oral azithromycin (500 mg OD × 2 weeks) and topical fortified cefazolin (5%, 4 hourly for 1 month) was initiated. Localised warm compresses were also advised. At mean follow-up of 13.5 months, both patients were symptom-free without epiphora. The conjunctival swabs were taken before starting antibiotics from the punctum region, showed growth of Staphylococcus aureus (n = 2).

The clinical details, misdiagnosis, microbiology, and follow-up of all patients is mentioned in Table 1. Overall, the patients visited treating ophthalmologists for a mean 4 times before presenting to us. This reflects the quantitative delay before an accurate treatment is started.

Table 1.

Details of misdiagnosed lacrimal canaliculitis patients.

| S. no. | Age/Sex | Chief complaints | Laterality | Duration (months) | Misdiagnosis | Treatment advised outside | Treatment given | Microbiology | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 62/F | Redness, discharge, ± pain | Left, inferior | 9 | Bacterial conjunctivitis, Chronic dacryocystitis | DCR | 3-snip punctoplasty + curettage | Staphylococcus aureus | 15 |

| 2. | 65.5/F | Discharge, redness | Left, superior | 18 | Bacterial conjunctivitis, Chronic dacryocystitis | DCR | 3-snip punctoplasty + curettage | Nocardia asteroids | 13 |

| 3. | 71/F | Watering, redness, discharge | Left, superior | 12 | Bacterial conjunctivitis, Chronic dacryocystitis | DCR | 3-snip punctoplasty + curettage | Actinomyces Israeli | 16 |

| 4. | 58/F | Redness, pain, watering | Left, superior | 12 | Medial chalazion | Incision & curettage | Conservative management | Staphylococcus aureus | 14 |

| 5. | 57.5/F | Redness, pain, watering | Right, inferior | 12 | Medial chalazion | Incision & curettage | Conservative management | Staphylococcus aureus | 13 |

F: Female, DCR: Dacryocystorhinostomy.

Discussion

PLC remains a frequently misdiagnosed pathology even by the speciality-trained ophthalmologists due to its overlapping presenting features. It is commonly misdiagnosed as chronic bacterial conjunctivitis, chronic dacryocystitis/PANDO and rarely as chalazion; hence PLC is often mismanaged. In our series, 2 patients were misdiagnosed as medial marginal chalazion which, to our knowledge, has never been reported in literature.

Despite the availability of sufficient literature, the lacrimal canaliculitis remains one of the most misdiagnosed medical disorders.3 Even though the classical clinical signs of lacrimal canaliculitis are known, the patients are undiagnosed and improperly treated. Previous single or multiple misdiagnosis has been reported by Anand et al.9 in 33–60% of cases, Pavilack5 in 45%, Vecsei et al.1 in 60%, and Briscoe et al.6 in 100%. An atypical location of a routine chalazion (medial to lacrimal punctum, no meibomian glands) should be suspected for a canalicular disorder.

We found classical pouting of punctum, peri-punctum hyperemia, and expressible granular discharge by pressing canaliculus in 3 patients who were misdiagnosed as chronic dacryocystitis/PANDO. To differentiate chronic dacryocystitis/PANDO from canaliculitis, the punctum and surrounding region would typically be normal in the former while the ROPLaS would usually be negative in the latter. In 2 patients, there was no classical pouting of punctum, but a yellowish hue/discolouration of canalicular region was noticed as a unique feature in both. This clinical sign has not been emphasized enough in existing literature and the presence of chalazion medial to punctum is anatomically not possible.

Lacrimal canaliculitis constitutes a mere 2% of the lacrimal pathologies which might be due to undiagnosed and misdiagnosed patients.3 Frequent misdiagnosis (33–100%) suggests a low index of clinical suspicion for primary as compared to the secondary variety.1, 3, 5 Though high-resolution ultrasound can be used as an investigating tool, the diagnosis is principally clinical.3

The medical management of PLC includes oral and topical antibiotics (penicillins, macrolides, tetracyclines etc.), oral antifungals, and hyperbaric 100% oxygen.3 Minimally invasive procedures like intra-canalicular irrigation with antibiotic solution or ointment, and punctum dilatation and reverse canalicular massage (milking), have shown positive results.8 The literature advocates surgical clearance of the canalicular tracts for PLC to provide long-term success with minimum recurrences.2 Punctoplasty and canaliculotomy has been added into the armamentarium to provide greater access to the infected tract by the curette.7 The recurrence rate of conservative treatment is 33% while for surgical management. It ranges from 0 to 20%.6, 9, 10

In conclusion, firstly, ophthalmologists should be aware and have a high index of suspicion for PLC. A meticulous slit-lamp clinical examination of the punctum and canalicular region is vital. Classical pouting of punctum and yellowish hue/discoloration of canaliculus may advocate lacrimal canaliculitis.

Footnotes

Prior presentation – “Poster – challenging cases” at Asia Pacific Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 2014 held at New Delhi (26–28th September, 2014).

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding sources: None.

Peer review under responsibility of the Iranian Society of Ophthalmology.

References

- 1.Vecsei V.P., Huber-Spitzy V., Arocker-Mettinger E., Steinkogler F.J. Canaliculitis: difficulties in diagnosis, differential diagnosis and comparison between conservative and surgical treatment. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208(6):314–317. doi: 10.1159/000310528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaliki S., Ali M.J., Honavar S.G., Chandrasekhar G., Naik M.N. Primary canaliculitis: clinical features, microbiological profile & management outcome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(5):355–360. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31825fb0cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman J.R., Markert M.S., Cohen A.J. Primary and secondary lacrimal canaliculitis: a review of literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(4):336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Y.Y., Yu W.K., Tsai C.C., Kao S.C., Kau H.C., Liu C.J. Clinical features, microbiological profiles and treatment outcome of lacrimal plug-related canaliculitis compared with those of primary canaliculitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(9):1285–1289. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavilack M.A., Frueh B.R. Thorough curettage in the treatment of chronic canaliculitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(2):200–202. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080140056026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briscoe D., Edelstein E., Zacharopoulos I., Keness Y., Kilman A., Zur F. Actinomyces canaliculitis: diagnosis of a masquerading disease. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242(8):682–686. doi: 10.1007/s00417-004-0871-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim U.R., Wadwekar B., Prajna L. Primary canaliculitis: the incidence, clinical features, outcome and long-term epiphora after snip–punctoplasty and curettage. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29(4):274–277. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu J., Liu Z., Mashaghi A., Sun X., Lu Y., Li Y. Novel therapy for primary canaliculitis: a pilot study of intracanalicular ophthalmic corticosteroid/antibiotic combination ointment infiltration. Med Baltim. 2015;94(39) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand S., Hollingworth K., Kumar V., Sandramouli S. Canaliculitis: the incidence of long-term epiphora following canaliculotomy. Orbit. 2004;23(1):19–26. doi: 10.1076/orbi.23.1.19.28985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin S.C., Kao S.C., Tsai C.C. Clinical characteristics and factors associated the outcome of lacrimal canaliculitis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(8):759–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]