Abstract

This study measured the effects of vitamin D (VD) supplementation on the underlying molecular pathways involved in renal and testicular damage induced by lead (Pb) toxicity. Thirty two adult male Wistar rats were divided equally into four groups that were treated individually or simultaneously, except the negative control, for four weeks with lead acetate in drinking water (1,000 mg/L) and/or intramuscular VD (1,000 IU/kg; 3 days/week). Pb toxicity markedly reduced serum VD and Ca2+, induced substantial renal and testicular injuries with concomitant significant alterations in the expression of VD metabolising enzymes, its receptor and binding protein, and the calcium sensing receptor. Pb also significantly promoted lipid peroxidation and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4 and TNF-α) in the organs of interest concomitantly with declines in several anti-oxidative markers (glutathione, glutathione peroxidase and catalase) and the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10. The co-administration of VD with Pb markedly mitigated renal and testicular injuries compared with positive controls. This was associated with restoration of the expression of VD related molecules, promotion of anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory markers, but tissue Pb concentrations were unaffected. In conclusion, this report is the first to reveal potential protective effects for VD against Pb-induced renal and testicular injuries via anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mechanisms.

Introduction

Lead (Pb) is a non-essential element that could result in serious health problems due to toxicity arising from environmental pollution1–3. The risk is significant with the World Health Organisation (WHO) reporting 853,000 deaths related to Pb toxicity in 20134. Ingesting contaminated food and water is the route of lead intoxication for the general population, while inhalation of polluted dust and fumes is more common in the occupational setting2. Accumulation of Pb in tissues induces cellular damage through oxidative stress following overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduction in the activities of cellular antioxidant system5–8. The metal also inhibits cellular energy production and induces apoptosis subsequent to mitochondrial impairment and DNA damage9,10. Additionally, Pb simultaneously upregulates and inhibits the production of several pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines11,12.

Pb poisoning provokes severe multiorgan damage, with chronic exposure increasing the risk of developing renal diseases1–3, and adverse reproductive consequences5,13. In this context, blood Pb levels greater than 60 μg/dL were shown to induce nephropathies characterised by tubular dysfunction and decreased creatinine clearance2,3,14. Prolonged exposure to Pb has also been reported to cause abnormal sex hormones levels and significantly lower sperm count that were morphologically abnormal and immotile15,16. The standard clinical management of lead poisoning encompasses the administration of chelators (e.g. succimer) and ensuring the avoidance of further exposure to contaminated sources4,17. However, controversies still surround the efficacy of chelators, since they are mainly capable of eliminating the metal from circulation, with little effects on tissue precipitates18–20. Therefore, there is still a compelling need to develop more potent chelators that could efficiently protect against Pb-induced tissue damage18–20.

Vitamin D (VD) is a steroid hormone that is mainly synthesised as a prohormone in the skin following exposure to sunlight and the production of active VD (VD3) occurs in renal proximal tubular cells by the actions of 1α hydroxylase (Cyp27b1) enzyme21,22. The transportation of VD in circulation is achieved by its binding protein (VDBP) and the hormone activities are mainly controlled by its catabolising enzyme, Cyp24a121. VD receptor (VDR) is located in the cytoplasm, and once activated, the receptor forms a complex with other nuclear receptors known as retinoid X receptors (RXR)23. The VDR/RXR complex then interacts with VD responsive elements on target genes to control their expression23. VD has a wide range of cytoprotective actions that include anti-fibrotic, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects, in addition to its known skeletal effects22,24. The classical actions of VD on Ca2+ homeostasis involve the regulation of several cellular proteins including the cell membrane calcium sensing receptor (CaSR)25. The activation of this receptor, which is coupled with G-protein, regulates the balance between intra- and extracellular Ca2+25. CaSR has been localised in several tissues, including kidney and testis, and its cellular expression has been shown to be regulated by VD26.

Little is currently known about the links between VD and Pb toxicity, and the available data is controversial. While polymorphisms in VDR gene have been associated with increases in blood Pb levels27,28, others have also reported significant negative correlations between blood levels of Pb and VD29,30. Additionally, numerous studies suggested that Pb enters the cytoplasm through Ca2+ channels31,32 and that Ca2+ channel blockers resulted in lower levels of Pb in renal tissues31. In contrast, Ca2+ consumption above the Dietary Reference Intake was associated with lower blood Pb levels30. The present study, was therefore designed to measure the effects VD3 supplementation on renal and testicular damage during chronic lead intoxication in rats together with the expression profiles of VD related molecules, oxidative stress markers and a panel of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the tissues of interest.

Results

Lead concentrations in renal and testicular tissues

The concentrations of Pb in renal tissues were markedly elevated in the positive control (PC) group (8.05 ± 3.12 µg/g) and the group treated simultaneously with both Pb and VD3 (P-VD) (7.12 ± 2.98 µg/g) compared with the negative control group (NC) (0.124 ± 0.04 µg/g; P = 0.02 × 10−16 and P = 0.03 × 10−11, respectively) and the normal animals treated with VD3 alone (N-VD) (0.094 ± 0.03 µg/g; P = 0.01 × 10−17 and P = 0.02 × 10−13, respectively). Similarly, testicular specimens form the PC (5.45 ± 2.32 µg/g) and P-VD (4.92 ± 2.18 µg/g) groups had significantly higher concentrations of lead than the NC (0.114 ± 0.03 µg/g; P = 0.04 × 10−8 and P = 0.05 × 10−6, respectively) and N-VD (0.088 ± 0.04 µg/g; P = 0.02 × 10−10 and P = 0.03 × 10−7, respectively) groups. However, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) between the PC and P-VD groups in renal and testicular Pb concentrations.

Biochemical Findings

The N-VD group had significantly higher levels of serum 25-OH VD (28.5 ± 5.20 ng/mL; P = 0.03) compared with the NC (23.05 ± 3.08 ng/mL). However, the serum concentrations of urea (38.66 ± 3.8 vs. 37.16 ± 3.6 mg/dL), creatinine (0.49 ± 0.04 vs. 0.55 ± 0.1 mg/dL), calcium (10.30 ± 0.38 vs. 9.90 ± 0.64 mg/dL) and total testosterone (4.40 ± 1.44 vs. 3.95 ± 0.91 ng/dL) were comparable between the N-VD and NC groups. The PC group showed markedly elevated serum creatinine (P = 0.0001) and urea (P = 0.00006), together with significantly lower levels of serum 25-OH vitamin D (P = 0.01), calcium (P = 0.005) and total testosterone (P = 0.009), compared with the NC group (Table 1). The simultaneous administration of VD3 with Pb significantly alleviated the effects of the heavy metal on serum creatinine (P = 0.007), urea (P = 0.03), 25-OH VD (P = 0.01), Ca2+ (P = 0.02) and total testosterone (P = 0.009) compared with the PC group. Additionally, the serum levels of all biochemical parameters were comparable between the P-VD and NC groups, except for urea, which was significantly higher in the former group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean ± SD of serum renal function parameters, calcium, 25-OH VD and total testosterone in the different study groups.

| Serum Parameters | Study Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NC (n = 8) | PC (n = 8) | P-VD (n = 8) | |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 37.16 ± 3.6 | 55.83 ± 5.7b | 45.80 ± 4.1b,c |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 0.78 ± 0.09b | 0.59 ± 0.07d |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.90 ± 0.64 | 8.63 ± 0.58a | 9.72 ± 0.48c |

| 25-OH VD (ng/mL) | 23.05 ± 3.08 | 15.33 ± 4.13b | 20.16 ± 2.04c |

| Testosterone (ng/mL) | 3.95 ± 0.91 | 2.38 ± 0.48b | 3.60 ± 0.61d |

(aP < 0.05 compared with the NC group; bP < 0.01 compared with the NC group; cP < 0.05 compared with the PC group and dP < 0.01 compared with the PC group).

Serum concentrations of targeted cytokines

Lead poisoning induced significant increases in serum IL-4 (P = 0.0008) and TNF-α (P = 0.001) that coincided with a significant decrease in serum IL-10 concentrations (P = 0.0003) compared with the NC group (Table 2). TNF-α and IL-10 were restored in the P-VD group to the levels observed in the NC group, and both cytokines were significantly different compared with the PC animals (P = 0.003 and P = 0.005, respectively). Although the serum concentrations of IL-4 were also significantly decreased in the P-VD compared with the PC group (P = 0.02), they remained significantly higher in this group (P = 0.0004) than the NC group (Table 2). The administration of VD3 in normal rats did not alter the levels of IL-4 (7.51 ± 1.04 pg/mL), TNF-α (23.66 ± 3.62 pg/mL) and IL-10 (11.51 ± 1.51 pg/mL) compared with the NC rats (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Mean ± SD of serum TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-10 in the different study groups.

| Serum cytokines (pg/mL) | Study Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NC (n = 8) | PC (n = 8) | P-VD (n = 8) | |

| TNF-α | 25.01 ± 3.73 | 37.33 ± 7.14b | 27.51 ± 4.81c |

| IL-4 | 7.83 ± 1.60 | 15.66 ± 2.33b | 11.16 ± 2.04b,c |

| IL-10 | 12.66 ± 2.22 | 7.01 ± 1.78b | 10.33 ± 1.86d |

(aP < 0.05 compared with the NC group; bP < 0.01 compared with the NC group; cP < 0.05 compared with the PC group and dP < 0.01 compared with the PC group).

Renal and testicular lipid peroxidation and antioxidant markers

There was no significant difference in the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in renal and testicular tissues between the NC and N-VD groups. However, The administrations of VD3 to normal animals induced significant elevations in renal and testicular levels of glutathione (GSH) (12.9%; P = 0.03 and 21.4%; P = 0.02, respectively) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) (44.5% ± 4.4; P = 0.009 and 72.9% ± 11.9; P = 0.0005, respectively) compared with the control group.

Prolonged exposure to Pb, within the PC group compared to the NC group, resulted in significant increases in renal (P = 0.0001) and testicular (P = 0.00005) tissues levels of MDA by 36% and 53%, respectively (Table 3). The levels of MDA in the kidney (P = 0.001) and testis (P = 0.03), obtained from the P-VD group and compared with PC, were significantly reduced by 22.8% and 16%, respectively. Although renal MDA concentrations were similar between the P-VD and NC groups, the lipid peroxidation marker remained significantly higher (P = 0.01) in the P-VD testicular tissues (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean ± SD of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant markers in renal and testicular tissue homogenates from all study groups.

| Tissue Parameters | Study Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC (n = 8) | PC (n = 8) | P-VD (n = 8) | ||

| MDA (nmol/g) | Kidney | 33.16 ± 4.75 | 45.10 ± 4.97b | 34.81 ± 3.85d |

| Testis | 25.16 ± 3.97 | 38.66 ± 5.61b | 32.50 ± 3.10b,c | |

| GSH (mg/g) | Kidney | 38.82 ± 5.31 | 29.65 ± 3.32b | 36.34 ± 4.54d |

| Testis | 24.17 ± 3.37 | 19.02 ± 3.78b | 22.16 ± 3.31 | |

| GPx (µg/mg) | Kidney | 3.93 ± 0.95 | 1.82 ± 0.70b | 3.52 ± 0.41d |

| Testis | 2.63 ± 0.98 | 1.58 ± 0.30a | 2.40 ± 0.48c | |

| CAT (U/mg) | Kidney | 245.8 ± 34.9 | 175.1 ± 17.8b | 222.6 ± 15.4d |

| Testis | 95.33 ± 16.9 | 65.50 ± 14.8a | 92.30 ± 9.8d | |

| SOD (U/mg) | Kidney | 103.2 ± 9.8 | 97.66 ± 16.2 | 104.51 ± 10.11 |

| Testis | 12.1 ± 2.28 | 10.66 ± 1.96 | 11.33 ± 2.71 | |

(aP < 0.05 compared with the NC group; bP < 0.01 compared with the NC group; cP < 0.05 compared with the PC group and dP < 0.01 compared with the PC group).

In contrast, the PC group showed prominent reductions in renal levels of GSH (23.6%; P = 0.002), GPx (53.7%; P = 0.001) and CAT (28.7%; P = 0.0009) than the NC group. Similarly, testicular levels of GSH (P = 0.04), GPx (P = 0.01) and CAT (P = 0.03) were also significantly decreased by 22.3%, 40% and 31.2%, respectively, in the PC group compared with the NC rats. However, there was no significant difference in the levels of SOD in both tissues between both groups (Table 3). The simultaneous administration of VD3 with Pb rescued the observed decreases in renal and testicular antioxidant markers, and the levels were then comparable to the NC group. All markers were significantly higher than the PC group, except for testicular GSH, which showed a non-significant decrease (Table 3).

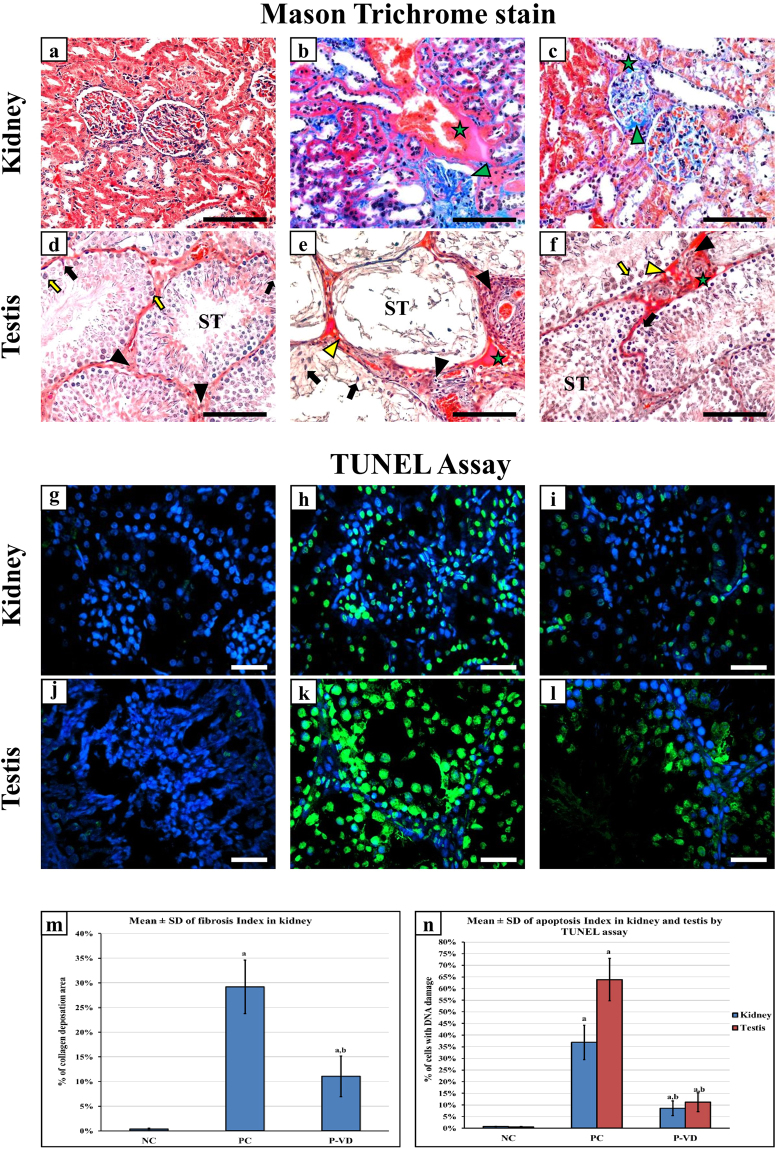

Effects of vitamin D3 on lead induced renal and testicular cell damage

Renal (Fig. 1a) and testicular (Fig. 1d) tissues from the NC group showed normal architecture with minimal/negligible collagen type I deposition by Mason trichrome stain. Coherently, a handful scattered apoptotic bodies were observed in normal kidney (Fig. 1g) and testis (Fig. 1j) using the TUNEL assay. Pb intoxication induced interstitial necrosis in kidneys and testicles of the PC group and was observed to be more pronounced in the testicular specimens. In more detail, renal tissue damage showed several areas of interstitial necrosis, glomerular and inter-tubular fibrosis, widening of tubular lumens and protrusion of tubular cell nuclei (Fig. 1b) with a significant increase in cell DNA damage (Fig. 1h). Pb-induced testicular damage showed severe interstitial hyaline degeneration, seminiferous tubule atrophy with almost complete loss of both germ and Sertoli cells (Fig. 1e), and many cells were also positive for apoptotic bodies (Fig. 1k).

Figure 1.

Histopathological features by Mason’s trichrome stain of renal and testicular tissues of the NC (a & d), PC (b & e), and P-VD (c & f) groups (40× objective, scale bar = 8 µm; green star = interstitial necrosis; green arrow head = collagen type I deposition in glomerulus; yellow arrow head = hyaline droplets; ST = seminiferous tubule; black arrow = Sertoli cell; black arrow head = Leydig cell and yellow arrow = spermatogonia). Cellular DNA damage was detected by TUNEL assay (Green fluorescent dye) in kidney and testis from the NC (a & g), PC (b & h), and P-VD (c & i) groups (40× objective; scale bar = 10 µm; positive nuclei are stained in green). Additionally, the renal fibrosis index (m) and renal and testicular apoptosis/necrosis index (n) are shown as bar graphs for the study groups. (a = P < 0.05 compared with NC group and b = P < 0.05 compared with PC group).

VD3 significantly decreased the amount of renal fibrosis (Fig. 1c) and the numbers of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 1i) in the P-VD group. Similar effects were also seen in testicular specimens, and the degeneration of interstitial tissue was significantly decreased with preservation of seminiferous tubule morphology, salvation of Sertoli and germ cells (Fig. 1f) and a significantly lower number of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 1l). Renal fibrosis index (Fig. 1m) and apoptosis/necrosis index of renal and testicular tissues (Fig. 1n) from all groups are shown as graph bars.

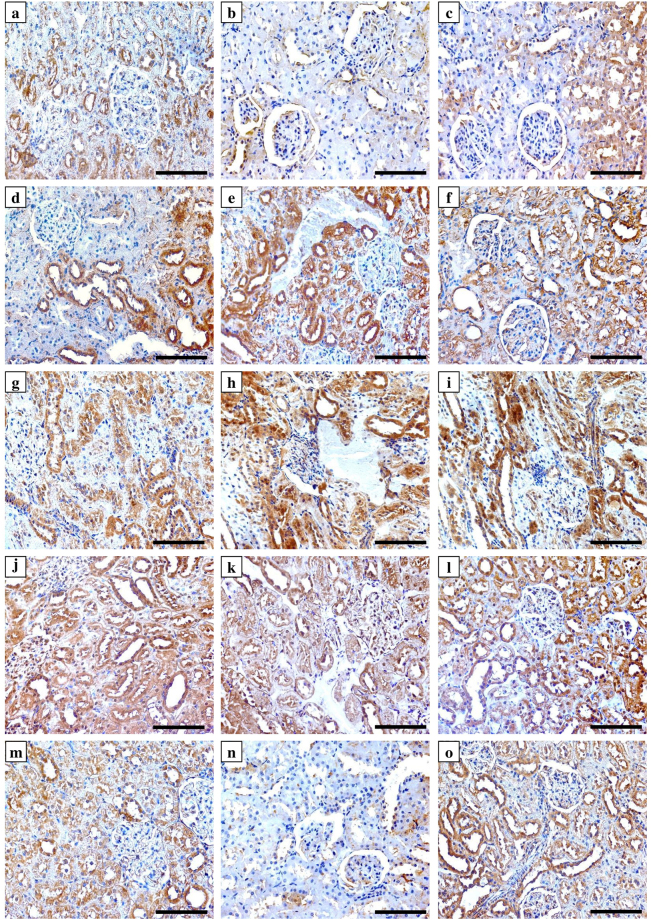

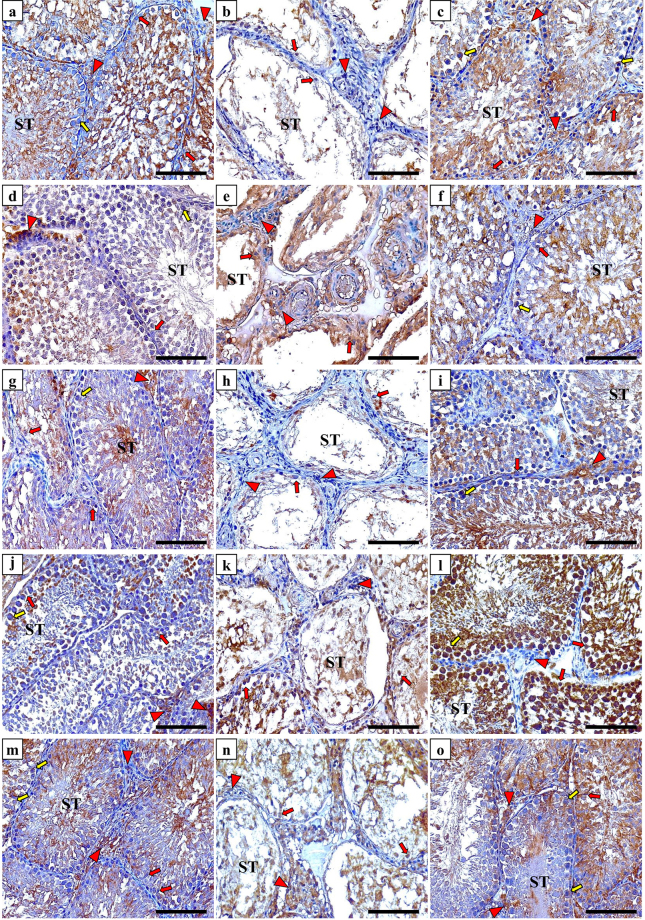

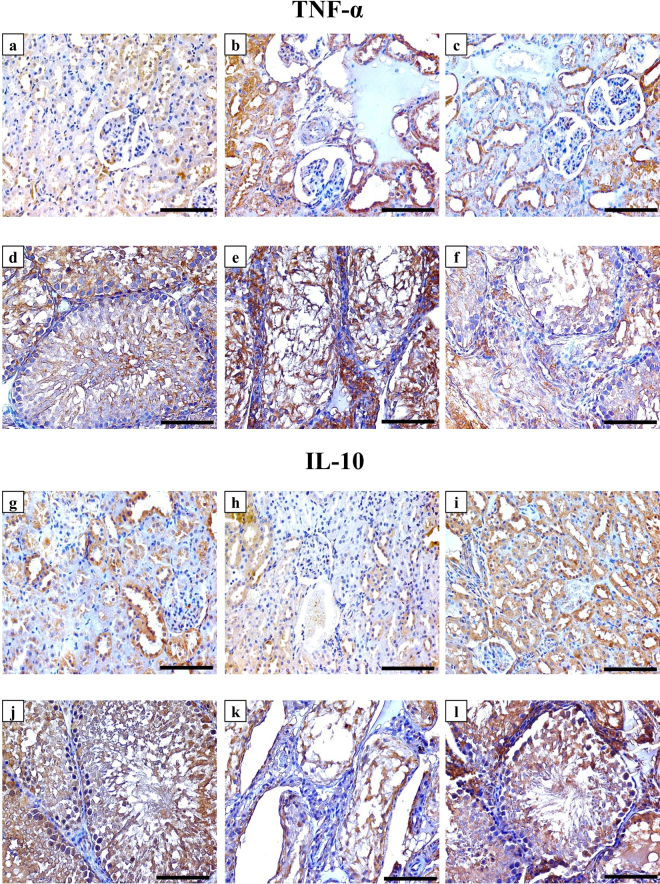

Immunohistochemistry of vitamin D related proteins and targeted cytokines

All target molecules were detected and the expression was localised in the renal and testicular tissues of the NC group. The antibodies against Cyp27b1 (Fig. 2a), Cyp24a1 (Fig. 2d), VDBP (Fig. 2g) and CaSR (Fig. 2m) clearly labelled the cytoplasm and apical border of renal tubular cells of the NC animal tissues, except for VDR, which showed nuclear localisation in glomerular and tubular cells (Fig. 2j). All VD related proteins (Fig. 3; left column) were also expressed by Sertoli cells and spermatogonium, in addition to primary and secondary spermatocytes within the seminiferous tubules of the NC group tissues. Furthermore, positive immunostain for Cyp27b1 (Fig. 3a), VDR (Fig. 3j) and CaSR (Fig. 3m) was also observed in Leydig cells. The expression of TNF-α and IL-10 was also detected in renal (Fig. 4, panels a & g) and testicular (Fig. 4, panels d & j) specimens of the NC group.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical expression of Cyp27b1 enzyme (upper row), Cyp24a1 enzyme (2nd row from top), VDBP (3rd row from top), VDR (4th row from top) and CaSR (bottom row) in kidney sections from the NC (left column), PC (middle column) and P-VD (right column) groups (40× objective, scale bar = 8 µm).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical expression of Cyp27b1 enzyme (upper row), Cyp24a1 enzyme (2nd row from top), VDBP (3rd row from top), VDR (4th row from top) and CaSR (bottom row) in testicular sections from the NC (left column), PC (middle column) and P-VD (right column) groups (40× objective; scale bar = 8 µm; ST = seminiferous tubule; red arrow = Sertoli cell; red arrow head = Leydig cell and yellow arrow = spermatogonia).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical expression of TNF-α and IL-10 in renal (1st and 3rd rows from top) and testicular (2nd and 4th rows from top) sections from the NC (left column), PC (middle column) and P-VD (right column) groups (40× objective, scale bar = 8 µm).

The PC group showed significant decreases than the NC group in the renal tissue expression of Cyp27b1 enzyme (Fig. 2b), VDR (Fig. 2k), CaSR (Fig. 2n) and IL-10 (Fig. 4b), especially around the damaged areas. Furthermore, there was a significant increase in renal Cyp24a1 (Fig. 2e), VDBP (Fig. 2h) and TNF-α (Fig. 4b) compared with the NC group (Table 4). Moreover, Pb poisoning also induced similar effects in testicular tissues in relation to the expression of VD synthesising (Fig. 3b) and catalysing (Fig. 3e) enzymes, VDR (Fig. 3k), CaSR (Fig. 3n), TNF-α (Fig. 4e) and IL-10 (Fig. 4h) compared with controls. However, there was a significant decrease in the expression of testicular VDBP (Fig. 3h) in the PC group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean ± SD of immunohistochemistry scores for Cyp27b1, Cyp24a1, VDBP, VDR, CaSR, TNF-α and IL-10 in renal and testicular specimens from the different study groups.

| Immunohistochemistry arbitrary scores | Study Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC (n = 8) | PC (n = 8) | P-VD (n = 8) | ||

| Cyp27b1 | Kidney | 148.2 ± 28.7 | 100.7 ± 31.1a | 174.6 ± 30.1c |

| Testis | 423.8.2 ± 52.6 | 89.3 ± 24.8b | 516.3.6 ± 52.3a,c | |

| Cyp24a1 | Kidney | 167.3 ± 34.4 | 354.5 ± 39.2b | 292.3 ± 27.2a,c |

| Testis | 108.4 ± 23.9 | 169.2 ± 33.3a | 365.7 ± 34.9a,c | |

| VDBP | Kidney | 319.7 ± 28.5 | 363.7 ± 37.6a | 314.2 ± 37.3b |

| Testis | 319.8 ± 46.4 | 159.3 ± 28.9b | 448.8 ± 51.7a.c | |

| VDR | Kidney | 471.6 ± 40.1 | 277.6 ± 23.1b | 394.7 ± 22.6a,d |

| Testis | 501.7 ± 57.4 | 350.1 ± 51.6a | 732.4 ± 61.1a,d | |

| CaSR | Kidney | 202.8 ± 29.4 | 62.8 ± 24.2b | 264.2 ± 29.6a,d |

| Testis | 479.8 ± 43.9 | 334.6 ± 22.2a | 462.8 ± 34.1c | |

| TNF-α | Kidney | 88.1 ± 19.2 | 215.9 ± 33.6b | 152.7 ± 24.6a,c |

| Testis | 243.6 ± 25.1 | 455.6 ± 37.7b | 173.5 ± 21.9a,c | |

| IL-10 | Kidney | 153.9 ± 26.9 | 76.8 ± 27.1a | 241.2 ± 22.9b,d |

| Testis | 527.2 ± 42.3 | 168.3 ± 19.8a | 510.4 ± 30.2d | |

(aP < 0.05 compared with the NC group; bP < 0.01 compared with the NC group; cP < 0.05 compared with the PC group and dP < 0.01 compared with the PC group).

The abnormal expression of VD associated molecules were restored in the P-VD group renal (Fig. 2; right column) and testicular (Fig. 3; right column) tissues compared with the PC group and the scores were comparable to control tissues (Table 4). Additionally, VD3 significantly downregulated the expression of TNF-α (Fig. 4; panels c & f) and promoted the expression of IL-10 (Fig. 4; panels i & l) in the kidney and testis (Table 4).

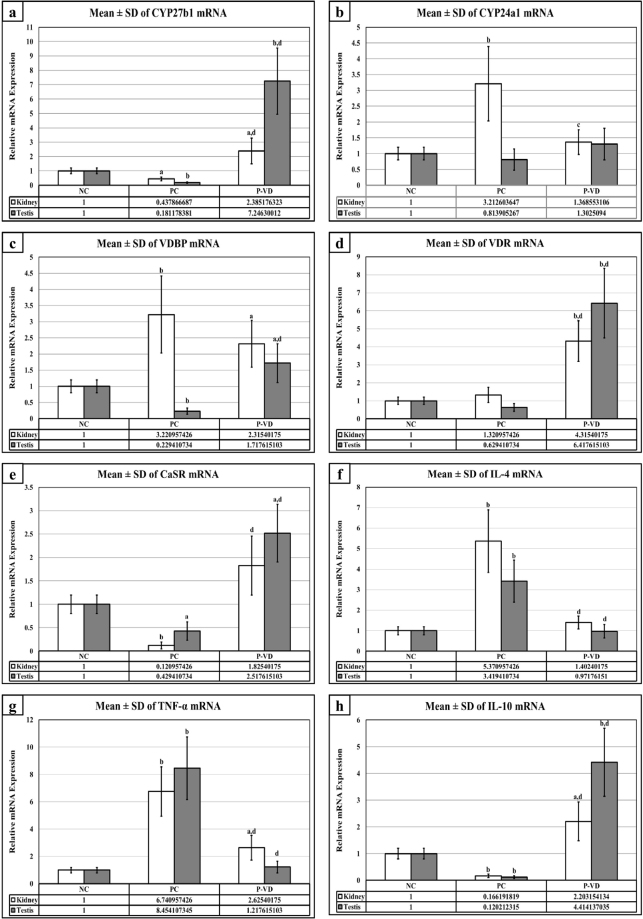

Renal and testicular gene expression of targeted molecules

In agreement with the immunohistochemistry results, the gene expression experiments revealed a significant decrease in the mRNAs of Cyp27b1 (2 folds), CaSR (10 folds) and IL-10 (10 folds) in kidney specimens from the PC group compared with NC. Additionally, there was a significant increase in the renal gene expression of Cyp24a1 (3 folds), VDBP (3 folds), IL-4 (5 folds) and TNF-α (7 folds) following Pb intoxication (Fig. 5). This was not, however, associated with any significant changes in the mRNA of VDR in renal tissues. Furthermore, similar observations were also detected in the gene expression of all candidate molecules by the testicular tissues following Pb intoxication, except for the catalysing enzyme, which showed no significant alteration together with a significant inhibition of VDBP gene (Fig. 5). Up-regulation in the mRNA of Cyp27b1, VDR, CaSR, and IL-10 with simultaneous decreases in the mRNA expression of IL-4 and TNF-α in both renal and testicular tissues of the P-VD group, were significantly different compared with the PC group. The results of all genes are illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Mean ± SD of messenger RNA relative expression of (a) Cyp27b1, (b) Cyp24a1, (c) VDBP, (d) VDR, (e) CaSR, (f) IL-4, (g) TNF-α and (h) IL-10 in the different study groups. (a = P < 0.05 compared with the NC group; b = P < 0.01 compared with the NC group; c = P < 0.05 compared with the PC group and d = P < 0.01 compared with the PC group).

Discussion

This study measured the reciprocal interactions between chronic lead intoxication and serum VD concentrations concomitantly with the effects of VD3 supplementation on several molecular pathways associated with Pb-induced tissue damage in kidneys and testes. The results showed that animals, chronically exposed to Pb, had significantly higher tissue contents of the heavy metal that coincided with significantly lower concentrations of serum 25-OH VD and Ca2+. Moreover, the mRNA and protein expression levels of VD synthesising enzyme, VDR and CaSR were downregulated with simultaneous marked increases in VDBP and Cyp24a1 in the kidney and testis of positive control animals.

Our results are in agreement with the findings of numerous earlier human studies that have reported inverse correlations between blood lead levels and the serum concentrations of both VD29,30,33 and Ca2+ 34–36. Skin exposure to ultraviolet rays is the main source of VD in the prohormone form, which is later transported to the liver to undergo the first hydroxylation step. Pb poisoning is known to provoke hepatotoxicity, and therefore, lead-induced liver damage could intervene with VD biogenesis14. Alternatively, the observed reduction in circulatory VD and the abnormal cellular expression of its machinery could also be related to Pb-induced nephrotoxicity1,14, since the active form of VD is produced in renal proximal tubular cells21,22. Therefore, we suggest that excess Pb deposition is tissues could result in abnormal cellular metabolism of VD by concurrently upregulating Cyp24a1 and inhibiting Cyp27b1 enzymes, especially in the major organs responsible for the production of VD, thus resulting in lower blood levels. However, more studies that involve skin and liver specimens are still required to support our proposals regarding the biological interactions between Pb toxicity and VD metabolising system.

Lead poisoning is a worldwide public health hazard and several studies have indicated the deleterious effects of Pb on kidney and testis12,17. Studies in humans have shown that high blood Pb level increases the risk of developing kidney diseases by affecting transportation in proximal tubules and diminishing creatinine clearance14. Experimental studies have also shown that prolonged exposure to lead resulted in renal cell injury, interstitial necrosis, tubular dysfunction and fibrosis of renal tissues7,8. Similarly, humans chronically exposed to Pb had impaired testicular functions in the form of low sperm count and the majority of sperm had abnormal morphology and were immotile15,16. Additionally, animal studies have revealed similar effects following chronic administration of Pb, and the testicular tissue showed interstitial degeneration and lower numbers of viable Sertoli, Leydig and germ cells together with significantly lower serum testosterone37–40.

The present study correlates with the abovementioned findings, since chronic ingestion of Pb induced the deposition of the toxic element in the kidney and testis, resulting in significant injuries of both organs and showed similar histopathological characteristics reported by earlier studies7,8,37–40. Our results also showed a significant increase in the lipid peroxidation marker, MDA, and significant decreases in anti-oxidant markers, GSH, GPx and CAT, in the tissues of interest. Additionally, the PC group had significantly higher levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-4, as well as lower level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, in serum and tissues. These findings provide further support to the notion that excess accumulation of Pb in renal and testicular tissues induces damages by increasing cellular ROS, oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory responses6–8.

In general, the interrelations between oxidative stress and inflammation are complex since one of them could alternatively be a cause and the other a consequence41. Additionally, the currently available data on Pb-induced tissue pathologies suggests that the metal upregulates several pro-inflammatory molecules together with elevations in oxidative stress markers6–8. In this context, a variety of human and experimental reports have demonstrated that Pb induces lipid peroxidation and accumulations of ROS in affected tissues, including kidney and testis5–7. Pb also promotes several pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-4, in serum and tissues6,42. Furthermore, the heavy metal have been shown to inhibit the expression of IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, in tissues and serum following chronic toxicity6,43. On the other hand, VD is currently regarded as a nutraceutical agent characterised by anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory actions in addition to its well-established roles in skeletal and calcium homeostasis22,24.

VD metabolising and signalling molecules have all been identified in renal tissues as well as male and female reproductive organs from different species21,44. The endogenous VD endocrine system has been shown to regulate vital functions in each organ including suppression of inflammation and oxidative stress44,45. In this regard, experimental studies have demonstrated that VD simultaneously promoted several anti-oxidant enzymes (e.g. Gpx1, and Prdx1) and downregulated a panel of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, TNF-α) in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy46. Consistently, others have also reported that chronic kidney disease induced by indoxyl sulfate in rats resulted in marked oxidative stress and inflammation through the up-regulation of VD catabolising enzyme47. Similar results have also been observed in testicular tissues following treatment of diabetic rats with VD45,48. Hence, we speculate that the observed pathological alterations in cellular VD system following Pb poisoning could be an additional mechanism by which the heavy metal promotes oxidative stress, inflammation and subsequently damages kidney and testis tissues47. In support with our suggestion above, VD3 in our study resulted in significant alleviations in renal and testicular tissue injuries observed in animals exposed to Pb-only. VD3 also restored and/or preserved the expression of its cellular endogenous molecules compared with positive controls, suggesting a positive feedback regulation, a common phenomenon previously reported by many studies following treatment with VD49–51.

Remarkably, none of the earlier studies measured the effects of VD supplementation on the adverse events associated with Pb poisoning. Our findings demonstrated that VD3 significantly diminished Pb-induced tissue damage in the kidney and testis. Tissue restoration/preservation was associated with significant increases in anti-oxidative markers, upregulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, and a marked decline in the levels of IL-4 and TNF-α. Similar observations have been previously reported for VD on oxidative stress markers and the expression of IL-10, IL-4 and TNF-α in chronic renal diseases and testicular dysfunction44,45. Hence, the present findings advocate that VD, through its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties, could negate the toxic effects of excess Pb on renal and testicular cells. However, the hormone had no effects on the tissue Pb concentration, since tissue specimens from the PC and P-VD groups displayed comparable levels of Pb in kidney and testicular specimens. Additionally, the applied VD dose in our study did not provoke hypercalcemia as shown by the biochemistry results. We, therefore, propose that future studies should include Ca2+ supplementation with or without higher doses of VD3, in order to measure and compare the potential effects of both agents on Pb precipitation in tissues, since the interconnections between VD and Pb could be calcium-dependent36. Furthermore, sperm count and morphology should also be included in future studies to affirm full restoration of testicular functions and fertility preservation.

In conclusion, this study is the first to display molecular mutual interactions between vitamin D and Pb toxicity. Additionally, this report demonstrated for the first time that VD3 has potential protective effects against Pb-induced renal and testicular injury through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant pathways. Nevertheless, more studies using calcium supplementation, alongside with exogenous VD3, are compulsory to explore the protective and therapeutic values of the VD endocrine system against toxicity induced by heavy metals.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and chemicals

Lead acetate trihydrate, Pb(CH3CO2)2·3H2O, purity 99.99% was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (MO, USA) and vitamin D3 intramuscular ampoules (100,000 IU/mL) were from Memphis Co. for Pharm. & Chem. Ind. (Cairo, Egypt).

Study Design and treatment protocols

All the experiments were approved by the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at Umm Al-Qura University and were in accordance with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments.

A total of 32 male Wister rats of 12 weeks of age and 220–250 gm of body weight each were housed in clean and sterile polyvinyl cages (4 rats/cage), maintained on a standard laboratory pellet diet and water ad libitum; and kept in a temperature-controlled air-conditioned at 22–24 °C and 12 h dark/light cycle. The animals were allocated randomly and equally into four groups (8 rats/group): NC group, PC group included animals that only received lead acetate, N-VD group consisted of normal rats injected with VD3, and the P-VD group simultaneously received lead acetate and VD3. Lead acetate was dissolved in drinking water (1,000 mg/L) and was given for 4 weeks to induce chronic toxicity as previously described52,53. VD3 was diluted in sterile saline and then given every other day for a total duration of 4 weeks (1,000 IU/Kg; 3 days/week) according to the previously published protocols by Abdelghany et al24. and Farhangi et al.54. However, VD3 was administrated intramuscularly in the present study to prevent any potential effect on the absorption rate of lead and/or VD3 if both were administrated orally.

Types of Samples

The animals were anaesthetised using diethyl ether (Fisher Scientific UK Ltd, Loughborough, UK) and 3 ml of blood were obtained from each animal in a plain tube from the middle canthus of the eye just before euthanasia. All blood samples were centrifuged and the serum was stored in −20 °C. The right kidney and testis were collected from each animal, cut in halves and a part from each organ was processed by conventional methods and finally embedded in paraffin. Another piece (0.5 gm) from the remaining half of each organ was digested with 6:1 wet acid ultrapure concentrated nitric acid: Perchloric acid using a Microwave Digestion System. The digested samples were then diluted with ultrapure deionised water and stored at −4 °C till processed to measure the concentrations of Pb.

The remaining left kidney and testis were cut in halves and one piece from each organ was immediately processed for protein extraction using 3 ml of RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA, USA) and electrical homogeniser. Following centrifugation, small aliquots (0.5 ml) of the resultant supernatant from each sample was placed in Eppendorf tube and the concentrations of total proteins were measured on Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA). All extracted renal and testicular total protein samples were then diluted with normal sterile saline for a final concentration of 500 µg/ml and stored in −20 °C.

The residual renal and testicular tissues were immersed in RNALater (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored in −80 °C. The extraction of total RNA was done using the Paris kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of RNA was assessed on a BioSpec-nano machine (Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and typically had an A260/A280 ratio of 1.7 to 1.9. The quantities of Total RNA samples were measured on Qubit Fluorometer and then aliquoted in 20 ng/µl and stored at −80 °C.

Lead tissue concentrations

The concentrations of renal and testicular Pb were measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 800, MA, USA) with hollow cathode lamp of Pb at wavelength of 283.3 nm as previously described42.

Serum Biochemical Parameters Assay

The serum levels of renal function markers (creatinine and urea), 25-OH vitamin D and calcium were measured using Cobas e411 (Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Enzyme linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Serum TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-10 were measured using specific rat ELISA kits (R&D systems, MN, USA). All samples were processed in duplicate on a fully automated ELISA system (Human Diagnostics, Germany) according the manufacturer’s guidelines. As reported by the manufacturer, the lowest detection ranges of TNF-α, IL-4 and IL-10 were 3.1 pg/mL, ≤3 pg/mL and 3 pg/mL, respectively. The levels of renal and testicular tissue antioxidant markers GSH, SOD, CAT, GPx and the lipid peroxidation marker, MDA, were also measured by ELISA (Cayman Chemical Co., MI, USA).

Histology Studies

Sections of 5 μm thickness from each tissue block were stained with Mason’s trichrome (Abcam, MA, USA) to assess fibrosis in the organs of interest. Two expert histopathologists and who were blind to the source group evaluated and scored renal and testicular fibrosis in all sections on an EVOS XL Core microscopy (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 10 random non-overlapping fields from each slide at ×400 magnification. Additionally, quantitative measurement of collagen deposition (fibrosis index %) was done using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) as previously described24 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

TUNEL Assay

Cell DNA damage and cell apoptosis/necrosis were assessed in the collected tissue specimens using the Click-iT™ TUNEL Alexa Fluor™ 488 Imaging Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and by following the manufacturer’s protocol. Stained slides were examined on an EVOS FL microscopy (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at ×400 magnifications. DNA damage was indicated by the emission of green fluorescence dye and the apoptotic/necrotic cells were counted using the cell counter tool provided with the microscope software (Supplementary Fig. 2). Apoptosis/necrosis index was measured by calculating the percentage of damaged cells in 15 random non-overlapping fields from each tissue section.

Immunohistochemistry

The primary polyclonal IgG antibodies (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) against VDR, CaSR, and VDBP were raised in rabbit, while those against Cyp27b1, Cyp24a1, IL-10 and TNF-α were raised in goat. An avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase technique using the Elite Vectastain Rabbit or Goat ABC kits (Vector Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) was applied to localise the target proteins by following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The concentrations were 1:200 for all primary antibodies. Negative control slides containing a section from each tissue block under investigation were treated identically to all other slides, but the primary antibodies were replaced with their corresponding primary normal goat or rabbit IgG antibodies (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) to control for non-specific staining.

The sections were observed on an EVOS XL Core microscope at ×400 magnification to evaluate the immunostain by two blinded expert observers. The images for each individual protein of interest were captured from 15 random non-overlapping fields from each tissue section. Captured images were later processed for digital image analysis with ImageJ software. Quantification of immunostain colour intensity together with the percentage of area of distribution for each molecule were identified and measured by the Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Image Analysis Toolbox in the software (supplementary Fig. 3) followed by reciprocal immunostain calculation as previously described55,56.

Quantitative RT-PCR

A high capacity RNA-to-cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for the synthesis of cDNA from 200 ng of total RNA and by following the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR was executed in triplicate wells on ABI® 7500 system using power SYBR Green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each PCR well included 10 µl SYBR Green, 7 µl DNase/RNase free water, 1 µl of each primer (5 pmol; supplementary table 1) and 1 µl cDNA (25 ng) and 40 cycles (95 °C/15 s and 60 °C/1 min) of amplification were performed as previously described24. Negative controls included one minus-reverse transcription control from the previous RT step and another minus-template PCR, in which nuclease free water was used as a template. The 2−∆∆Ct method was used to perform relative quantitative gene expression of rat CYP27B1, CYP24A1, VDR, VDBP, CaSR, IL4, IL10 and TNF-α genes. Rat β-actin gene showed the most consistent results among the three tested reference genes and was used to normalise the Ct values of the genes of interest. The results are expressed as fold-change compared with the NC group.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 16 was used for statistical analysis. All data were assessed for normality and homogeneity by the Kolmogorov and Smirnoff test and Levene test, respectively. One way ANOVA followed by the LSD post hoc test were used to compare between the study groups. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Availability of materials and data

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Akhmed Aslam, Assistant Professor of immunology, Laboratory Medicine Department, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Umm Al-Qura University, for proof-editing the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors read and approved the submitted manuscript. M.A.B. was involved in study design, supervision of laboratory experiments, analysis of data and drafting the manuscript. A.H.A. shared in the study design, collection of samples, supervision of histopathology and immunohistochemistry experiments, analysis of data and writing of manuscript. M.E.B. participated in the study design, treatment of animals and collection of samples, supervision of biochemical studies and ELISA, analysis of data and drafting the manuscript. J.A. participated in the treatment of animals, acquisition of data and molecular laboratory and ELISA experiments. S.I. helped in animal treatment, conduction of gross and microscopic experiments and processing of immunohistochemistry. B.R. conceived the study, participated in the supervision of laboratory experiments, analysis and interpretation of the results and writing of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-23258-w.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Caito, S., Lopes, A., Paoliello, M. M. B., & Aschner, M. Toxicology of Lead and Its Damage to Mammalian Organs. 2017/07/22 ed. Met Ions Life Sci. Vol. 17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Ericson B, et al. The Global Burden of Lead Toxicity Attributable to Informal Used Lead-Acid Battery Sites. Ann Glob Health. 2016;82:686–699. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haryanto B. Lead exposure from battery recycling in Indonesia. Rev Environ Health. 2016;31:13–6. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2015-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). Lead poisoning and health. 2016; Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs379/en/ [Accessed 2017 28/09].

- 5.Gandhi J, et al. Impaired hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis activity, spermatogenesis, and sperm function promote infertility in males with lead poisoning. Zygote. 2017;25:103–110. doi: 10.1017/S0967199417000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gargouri M, et al. Immunomodulatory and antioxidant protective effect of Sarcocornia perennis L. (swampfire) in lead intoxicated rat. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2017;27:697–706. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2017.1351018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, et al. The Protective Effect of Baicalin Against Lead-Induced Renal Oxidative Damage in Mice. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;175:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang, Y. S. et al Accumulation of methylglyoxal and d-lactate in Pb-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Biomed Chromatogr; 31: p. (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Liu J, et al. Mitochondria defects are involved in lead-acetate-induced adult hematopoietic stem cell decline. Toxicol Lett. 2015;235:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobrakowski M, et al. Oxidative DNA damage and oxidative stress in lead-exposed workers. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2017;36:744–754. doi: 10.1177/0960327116665674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirivarasai J, et al. Association between inflammatory marker, environmental lead exposure, and glutathione S-transferase gene. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:474963. doi: 10.1155/2013/474963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Machon-Grecka A, et al. The influence of occupational chronic lead exposure on the levels of selected pro-inflammatory cytokines and angiogenic factors. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2017;36:467–473. doi: 10.1177/0960327117703688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigeh M, Smith DR, Hsu PC. How does lead induce male infertility? Iran J Reprod Med. 2011;9:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matovic V, Buha A, Ethukic-Cosic D, Bulat Z. Insight into the oxidative stress induced by lead and/or cadmium in blood, liver and kidneys. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;78:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Telisman S, Colak B, Pizent A, Jurasovic J, Cvitkovic P. Reproductive toxicity of low-level lead exposure in men. Environ Res. 2007;105:256–66. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meeker JD, et al. Environmental exposure to metals and male reproductive hormones: circulating testosterone is inversely associated with blood molybdenum. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohl, H. R., Ingber, S. Z., & Abadin, H. G. Historical View on Lead: Guidelines and Regulations. Met Ions Life Sci. Vol. 17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kosnett MJ. Chelation for heavy metals (arsenic, lead, and mercury): protective or perilous? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:412–5. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith D, Strupp BJ. The scientific basis for chelation: animal studies and lead chelation. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:326–38. doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0339-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersen O, Aaseth J. A review of pitfalls and progress in chelation treatment of metal poisonings. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2016;38:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Refaat B, et al. Characterisation of vitamin D-related molecules and calcium-sensing receptor in human Fallopian tube during the menstrual cycle and in ectopic pregnancy. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;368:201–213. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Refaat B, El-Shemi AG, Ashshi A, Azhar E. Vitamin D and chronic hepatitis C: effects on success rate and prevention of side effects associated with pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:10284–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlberg C, Campbell MJ. Vitamin D receptor signaling mechanisms: integrated actions of a well-defined transcription factor. Steroids. 2013;78:127–36. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelghany AH, BaSalamah MA, Idris S, Ahmad J, Refaat B. The fibrolytic potentials of vitamin D and thymoquinone remedial therapies: insights from liver fibrosis established by CCl4 in rats. J Transl Med. 2016;14:281. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1040-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Fernandez I, Schepelmann M, Brennan SC, Yarova PL, Riccardi D. The calcium-sensing receptor: one of a kind. Exp Physiol. 2015;100:1392–9. doi: 10.1113/EP085137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow EC, Quach HP, Vieth R, Pang KS. Temporal changes in tissue 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, vitamin D receptor target genes, and calcium and PTH levels after 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E977–89. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00489.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Liu JW, Zhao JX, Cui J, Tian W. Influence of vitamin D receptor haplotypes on blood lead concentrations in environmentally exposed children of Uygur and Han populations. Biomarkers. 2010;15:232–7. doi: 10.3109/13547500903444880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pawlas N, et al. Modification by the genes ALAD and VDR of lead-induced cognitive effects in children. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang L, et al. Association of 25-hydroxyvitamin D with Hb and lead in children: a Chinese population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:827–32. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson LW, Cromer BA, Panneerselvamm A. Association between bone turnover, micronutrient intake, and blood lead levels in pre- and postmenopausal women, NHANES 1999-2002. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1590–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, et al. Nephroprotective effect of calcium channel blockers against toxicity of lead exposure in mice. Toxicol Lett. 2013;218:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang H, Li W, Xue Y, Zou F. TRPC1 is involved in Ca(2)(+) influx and cytotoxicity following Pb(2)(+) exposure in human embryonic kidney cells. Toxicol Lett. 2014;229:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y, et al. Relation of nutrition to bone lead and blood lead levels in middle-aged to elderly men. The Normative Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:1162–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zentner LE, Rondo PH, Duran MC, Oliveira JM. Relationships of blood lead to calcium, iron, and vitamin C intakes in Brazilian pregnant women. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:100–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ettinger AS, et al. Effect of calcium supplementation on blood lead levels in pregnancy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:26–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groleau V, et al. Blood lead concentration is not altered by high-dose vitamin D supplementation in children and young adults with HIV. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:316–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182758c4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Priya PH, Reddy PS. Effect of restraint stress on lead-induced male reproductive toxicity in rats. J Exp Zool A Ecol Genet Physiol. 2012;317:455–65. doi: 10.1002/jez.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayinde OC, Ogunnowo S, Ogedegbe RA. Influence of Vitamin C and Vitamin E on testicular zinc content and testicular toxicity in lead exposed albino rats. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;13:17. doi: 10.1186/2050-6511-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reshma Anjum M, Sreenivasula Reddy P. Recovery of lead-induced suppressed reproduction in male rats by testosterone. Andrologia. 2015;47:560–7. doi: 10.1111/and.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jegede AI, Offor U, Azu OO, Akinloye O. Red Palm Oil Attenuates Lead Acetate Induced Testicular Damage in Adult Male Sprague-Dawley Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:130261. doi: 10.1155/2015/130261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rath E, Haller D. Inflammation and cellular stress: a mechanistic link between immune-mediated and metabolically driven pathologies. Eur J Nutr. 2011;50:219–33. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasperczyk A, Dobrakowski M, Czuba ZP, Horak S, Kasperczyk S. Environmental exposure to lead induces oxidative stress and modulates the function of the antioxidant defense system and the immune system in the semen of males with normal semen profile. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;284:339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasten-Jolly J, Pabello N, Bolivar VJ, Lawrence DA. Developmental lead effects on behavior and brain gene expression in male and female BALB/cAnNTac mice. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:1005–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mansouri L, et al. Vitamin D receptor activation reduces inflammatory cytokines and plasma MicroRNAs in moderate chronic kidney disease - a randomized trial. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:161. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0576-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding C, et al. Vitamin D supplement improved testicular function in diabetic rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;473:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agharazii M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species as mediators of chronic kidney disease-related vascular calcification. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:746–55. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Gao Z, Wang L, Gao Y. Upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB activity mediates CYP24 expression and reactive oxygen species production in indoxyl sulfate-induced chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2016;21:774–81. doi: 10.1111/nep.12673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamden K, et al. Inhibitory effects of 1alpha, 25dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Ajuga iva extract on oxidative stress, toxicity and hypo-fertility in diabetic rat testes. J Physiol Biochem. 2008;64:231–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03216108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahearn TU, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the effects of supplemental calcium and vitamin D3 on markers of their metabolism in normal mucosa of colorectal adenoma patients. Cancer Res. 2011;71:413–23. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milczarek M, Filip-Psurska B, Swietnicki W, Kutner A, Wietrzyk J. Vitamin D analogs combined with 5-fluorouracil in human HT-29 colon cancer treatment. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:491–504. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carvalho JTG, et al. Cholecalciferol decreases inflammation and improves vitamin D regulatory enzymes in lymphocytes in the uremic environment: A randomized controlled pilot trial. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Velaga MK, Yallapragada PR, Williams D, Rajanna S, Bettaiya R. Hydroalcoholic seed extract of Coriandrum sativum (Coriander) alleviates lead-induced oxidative stress in different regions of rat brain. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;159:351–63. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-9989-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manoj Kumar V, et al. Protective effect of Allium sativum (garlic) aqueous extract against lead-induced oxidative stress in the rat brain, liver, and kidney. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2017;24:1544–1552. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7923-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farhangi MA, Nameni G, Hajiluian G, Mesgari-Abbasi M. Cardiac tissue oxidative stress and inflammation after vitamin D administrations in high fat- diet induced obese rats. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:161. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0597-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen, D., Zhou, T., Shu, J., & Mao, J. Quantifying chromogen intensity in immunohistochemistry via reciprocal intensity. Cancer InCytes; 2: p. e (2013).

- 56.Shu, J., Qiu, G., & Mohammad, I. A Semi-automatic Image Analysis Tool for Biomarker Detection in Immunohistochemistry Analysis. In 2013SeventhInternationalConferenceonImageandGraphics (2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.