Abstract

Recent crystallographic structures of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) have greatly advanced our understanding of the recognition of their diverse agonist and antagonist ligands. We illustrate here how this applies to A2A adenosine receptors (ARs) and to P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors (P2YRs) for ADP. These X-ray structures have impacted the medicinal chemistry aimed at discovering new ligands for these two receptor families, including receptors that have not yet been crystallized but are closely related to the known structures. In this Chapter, we discuss recent structure-based drug design projects that led to the discovery of: (i) novel A3AR agonists based on a highly rigidified (N)-methanocarba scaffold for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain and other conditions, (ii) fluorescent probes of the ARs and P2Y14R, as chemical tools for structural probing of these GPCRs and for improving assay capabilities, and (iii) new more drug-like antagonists of the inflammation-related P2Y14R. We also describe the computationally enabled molecular recognition of positive (for A3AR) and negative (P2Y1R) allosteric modulators that in some cases shown to be consistent with structure-activity relationship (SAR) data. Thus, computational modeling has become an essential tool for the design of purine receptor ligands.

Keywords: adenosine receptor, P2Y receptor, structure-based drug design, X-ray crystallography, nucleosides, nucleotides

1. Introduction

GPCR ligands represent 33% of the small-molecule drugs that target major protein families [1]. The study of GPCR structure and function has been revolutionized as a result of new X-ray crystallographic findings and correlation with the structure activity relationships (SAR) and pharmacology of their ligands [2–5]. We present purine receptors as examples of GPCR families that have benefited enormously from these new high-resolution receptor structures. Purinergic signaling is an element in the control of many human physiological functions. The signaling interactions associated with extracellular purines and pyrimidines, loosely referred to as the “purinergic signalome”, consists of twelve G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), i.e. activated by adenosine (four adenosine receptors, ARs) and nucleotides (eight P2YRs), and seven distinct subunits of multimeric ATP-gated P2X ion channels [6,7]. Among the GPCRs, the ARs respond principally to adenine nucleosides and the P2YRs respond to adenine and uracil nucleotides. These receptors can be activated or blocked with small molecule modulators, some of which have entered clinical trials or been approved as diagnostic probes and agents for treating chronic diseases. In addition to orthosteric ligands, i.e. binding in the same site as native ligand, allosteric modulators, which bind at a separate site, are being explored for the purine receptors.

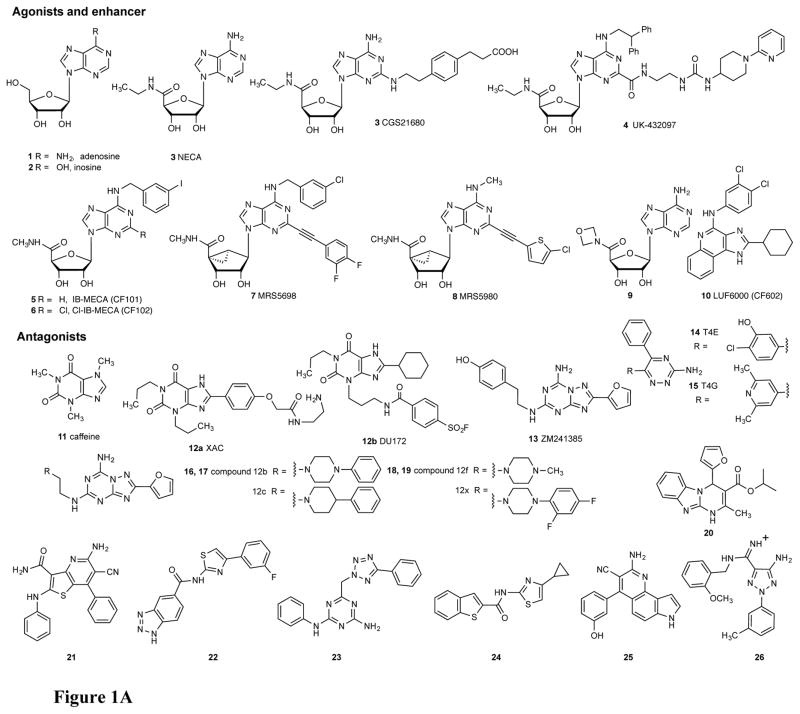

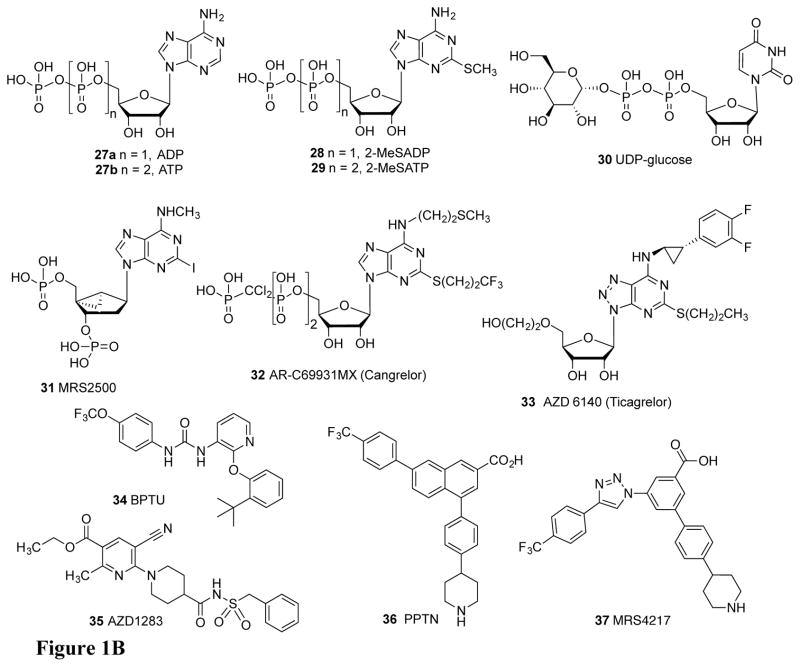

Furthermore, inhibition, by small molecules, of the enzymes that regulate the levels of the native AR agonists (Figure 1A) and native P2YR agonists (Figure 1B) and inhibitors of nucleoside transporters add another dimension to the exogenous control of this system [8]. Some of these extracellular enzymes are: CD39 (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1, ENTPD1), which hydrolyzes ATP 27b to ADP 27a and to AMP; CD73 (ecto-5′-nucleotidase, 5′-NT), which hydrolyzes AMP to adenosine 1, and adenosine deaminase, which converts adenosine to inosine 2. Adenosine kinase that forms AMP is an intracellular enzyme, but it tends to reduce the pool of available adenosine both inside and outside the cell, because of nucleoside transporters such as the equilibrative ENT1 that allow adenosine to cross the cell membrane [9]. The overall importance of the purinergic signalome is consistent with its being well-conserved throughout evolution as indicated by the phylogenetic relationships of the receptor family members [10,11]. We use convergent approaches, i.e. medicinal chemical, pharmacological, and structural, to discover new agonists, antagonists and inhibitors to modulate the purinergic signalome (Figure 1) [12–14]. There are four subtypes of ARs: Gi-coupled A1 and A3ARs and Gs-coupled A2A and A2BARs. Caffeine 11, the most widely consumed psychoactive drug, acts as a competitive, nonselective inhibitor of adenosine binding at the ARs. There are two subfamilies of P2YRs: five Gq-coupled P2Y1-like receptors (P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, P2Y11) and three Gi-coupled P2Y12-like receptors (P2Y12, P2Y13, P2Y14). However, the diversity of endogenous nucleotide agonists does not follow the division of subtypes based on G protein coupling. P2Y2, P2Y4, P2Y6, and P2Y14Rs can be activated by uracil nucleotides, while P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y11, P2Y12, and P2Y13 are activated by adenine nucleotides. The only subtype that is associated with well-validated therapeutics is P2Y12R, for which antagonists act as antithrombotic agents by blocking the action of ADP 27a on platelets [15].

Figure 1.

Structures of ligands described in the text for the: A) AR and B) P2YR families. The native agonists are adenosine (1) and inosine (2), to a lesser extent, for ARs and ADP (26), ATP (27), UDP-glucose (30), and UDP and UTP (not shown) for the P2YRs.

Since 2007, numerous high-resolution X-ray structures of the human (h) A2AAR and P2Y1 and P2Y12Rs have been reported (Table 1) [16–23]. Recently, the structure of the hA1AR was also solved [24]. These structural advances have opened new opportunities to rationally design ligands, both by structural enhancement of known agonists and antagonists and through the in silico screening and modeling of novel chemotypes. Research based on these GPCR X-ray structures has also led to advances regarding the other two AR subtypes that have not yet been crystallized but are closely related to the known A2AAR and A1AR structures. Similarly, closely related homology models are predictive of ligand recognition at P2YR subtypes other than P2Y1 and P2Y12Rs. Chemical tools for the crystallized receptors and related subtypes, such as high affinity fluorescent probes, were designed with the aid of molecular modeling and applied to drug discovery, including homology modeling, docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The importance of molecular modeling in the discovery of new purinergic ligands has therefore increased in recent years.

Table 1.

Reported X-ray crystal structures of purine receptors (all human) and methods used in the determination.

| Receptor, Ligand | Method,a Resolution (Å) | PBD ID: | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine A2AAR agonists | |||

| adenosine (1) | StaR (5), 3.0 | 2YDO | Lebon et al [18] |

| NECA (3) | StaR (5), 2.6 | 2YDV | Lebon et al [18] |

| UK432097 (4) | T4L(IL3)-ΔC, 2.71 | 3QAK | Xu et al [17] |

| CGS21680 (3) | StaR (5), 2.6 | 4UG2 | Lebon et al [46] |

| StaR (5), 2.6 | 4UHR | Lebon et al [46] | |

| Adenosine A1AR antagonist | |||

| DU172 (12b) | bRIL(IL3)-ΔC (9)b, 3.2 | 5UEN | Glukhova et al [24] |

| Adenosine A2AAR antagonists | |||

| ZM241385 (13) | T4L(IL3), 2.6 | 3EML | Jaakola et al [16] |

| StaR (8), 3.3 | 3PWH | Doré et al [30] | |

| Fab2838 (1), 2.7 | 3VG9 | Hino et al [100] | |

| Fab2838 (1), 3.1 | 3VGA | Hino et al [100] | |

| bRIL(IL3)-ΔC (3), 1.8 | 4EIY | Liu et al [19] | |

| StaR2-bRIL(IL3) (11), 1.72 | 5IU4 | Segala et al [70] | |

| caffeine (11) | StaR (8), 3.6 | 3RFM | Doré et al [30] |

| XAC (12a) | StaR (8), 3.31 | 3REY | Doré et al [30] |

| T4E (14) | StaR (8), 3.34 | 3UZC | Congreve et al [63] |

| T4G (15) | StaR (8), 3.27 | 3UZA | Congreve et al [63] |

| 12c (17) | StaR2-bRIL(IL3) (10), 1.9 | 5IU7 | Segala et al [70] |

| 12f (18) | StaR2-bRIL(IL3) (12), 2.0 | 5IU8 | Segala et al [70] |

| 12b (16) | StaR2-bRIL(IL3) (12), 2.2 | 5IUA | Segala et al [70] |

| 12x (19) | StaR2-bRIL(IL3) (10), 2.1 | 5IUB | Segala et al [70] |

| Cmpd-1 (26) | bRIL(IL3), 3.5 | 5UIG | Sun et al [53] |

| Adenosine A2AAR - other | |||

| engineered G protein | StaR (18), 3.4 | 5G53 | Carpenter et al [49] |

| na | SAD/XFEL (3), 2.5 | 5K2A | Batyuk et al [43] |

| na | MR/XFEL (3), 2.5 | 5K2B | Batyuk et al [43] |

| na | SAD/XFEL (3), 1.9 | 5K2C | Batyuk et al [43] |

| na | MR/XFEL (3), 1.9 | 5K2D | Batyuk et al [43] |

| P2Y1R antagonists | |||

| MRS2500 (31) | rub(IL3) (1), 2.7 | 4XNW | D. Zhang et al [22] |

| BPTU (34) | bRIL(N-term) (1), 2.2 | 4XNV | D. Zhang et al [22] |

| P2Y12R antagonist | |||

| AZD1283 (35) | bRIL(IL3) (4), 2.62 | 4NTJ | K. Zhang et al [20] |

| P2Y12R agonists | |||

| 2-MeSADP (28) | bRIL(IL3) (4), 2.5 | 4PXZ | K. Zhang et al [21] |

| 2-MeSATP (partial agonist, 29) | bRIL(IL3) (4), 3.1 | 4PY0 | K. Zhang et al [21] |

Construct or stabilization method. Number of mutations, if present, is given in parentheses, and if StaR or fusion construct (protein and location). T4L, cysteine-free phage T4 lysozyme; bRIL, thermostabilized apocytochrome b562RIL (e.g. A23-L128); ΔC, truncated C-terminus. Fab, antibody Fab fragment; N-term, N-terminus; rub, M1–E54 of rubredoxin; XFEL, X-ray free-electron laser; MR, molecular replacement method; sulfur phasing with SAD, single-wavelength anomalous dispersion; na, not applicable.

Construct is substituted with N159A (glycosylation site) and residues of the A2AAR at 220–228 (“to optimize bRIL insertion sites”) [24].

2. Materials

2.1. X-ray structures of complexes of purine receptors

The pace of reports on X-ray crystallographic GPCR structures, which are membrane-bound, has recently accelerated due to methodological advances [25–29]. Although it is not yet a routine process, and not amenable to the high-throughput methods applied to X-ray crystallography of soluble proteins, the several hundred structures, corresponding to dozens of GPCRs in different complexes, have already turned the tide in drug discovery approaches for this important superfamily of drug targets. We analyze the current state of knowledge of purine receptors as an illustration.

2.1.1. X-ray structures of the A1AR and A2AAR

The first structure of any purine receptor was an A2AAR complex with potent antagonist 4-[2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-yl-amino]ethyl]phenol (ZM241385, 13) reported in 2007 [16]. The overall ligand arrangement was roughly perpendicular to the membrane plane, in contrast to other GPCR structures. This general orientation of the various ligands as stretching from the pharmacophore binding site toward the outer surface applies to various ligands, such as the A2AAR structure in complex with the high affinity xanthine amine congener (XAC, 12a) antagonist [30]. This ligand arrangement – roughly parallel to the TMs (transmembrane domains) - was anticipated by earlier modeling and by the many chain-functionalized analogues of agonists and antagonists, which suggested that the distal tethered portions of the molecules were exposed to the medium. There is more freedom of substitution on the distal portions, because they are not limited by the steric constraints of the pharmacophore binding site [14,31,32].

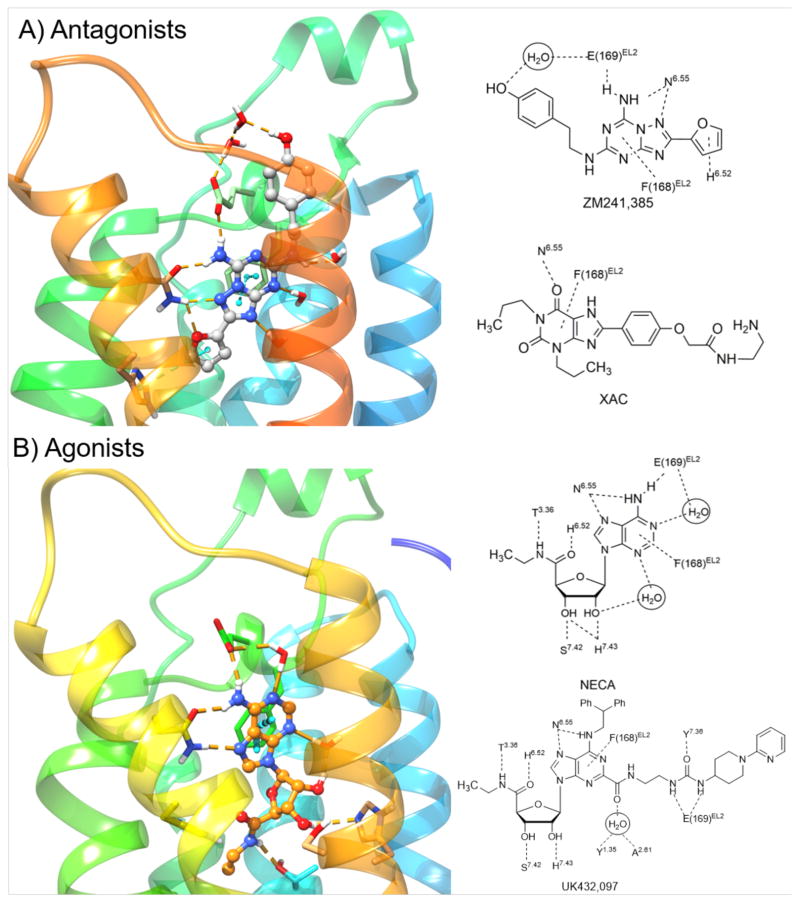

Coordination of triazolo-triazine ZM241385 13 and other antagonists in the A2AAR binding site (Figure 2A) occurs through both H-bonding and interactions with hydrophobic side chains, such as Leu6.51 (using Ballesteros-Weinstein convention for amino acid numbering in the TMs [33]). The heterocyclic ring forms π-π stacking with Phe168 (EL2). A conserved Asn6.55 (Asn253 in the A2AAR) forms bidentate H-bonds with the exocyclic amine and a triazole ring nitrogen atom, and the exocyclic amine also H-bonds with Glu169 in EL2 (Figure 2B). There are differences in the position of the 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl side chain of ZM241385 between different reported structures [16,30], which suggests that this moiety, which approaches the receptor’s exofacial side, has more conformational freedom than the heterocyclic pharmacophore. This is consistent with greater flexibility expected for the EL region of the receptor.

Figure 2.

Left panel: High-resolution X-ray crystallographic structures of the hA2AAR [19] with A) ZM241385 (13) and B) NECA [18] (3). Right panel: Contacts between four co-crystallized ligands and the hA2AAR are depicted on the right.

The highest resolution structure (1.8 Å) of an A2AAR in complex with ZM241385 13 was recently reported and shows unprecedented detail of bound water molecules and the conserved site for sodium ion binding at Asp2.50 in TM2 [19]. This sodium ion is proposed to act as a negative allosteric modulator of agonist binding at GPCRs in general [75]. This structural knowledge has been recently exploited to design new 5′-substituted amiloride analogues binding at the sodium site that resulted potent hA2AAR allosteric modulators [34]. Moreover, the role of the energetic contributions of water molecules in A2AAR antagonist binding had been anticipated in a study aimed at rationalizing the SAR of triazolylpurine analogues using the WaterMap software package [35]. The role of waters in GPCR ligand recognition represents a challenge for accurate prediction of ligand binding mode during virtual screening campaigns [36].

GPCRs with numerous stabilizing mutations (StaRs) have been developed as a core technology for structural biology and drug discovery [37]. These mutations are usually placed outside the binding site to avoid disruption of the drug-receptor interaction. Using multiple stabilizing mutations, many GPCRs can be crystallized with a wide range of agonist and antagonist ligands. Separate mutation sets were found to stabilize the conformation needed for binding either agonist or antagonist; thus, the StaRs can be customized for discovery of each ligand type. Furthermore, biophysical mapping of the binding site contour for a given class of congeneric ligands, such as chromones and triazines, can be performed [23,38,39]. Biophysical mapping has led to the structure-based optimization of new A2AAR antagonists, such as a 1,2,4-triazine T4E 14, of which the most advanced analogues are on a translational path for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and cancer. This effort has resulted in a candidate molecule for cancer co-therapy HTL1071 (AZD4635, structure not disclosed) that is in a Phase 1 trial in combination with durvalumab, targeting programmed death ligand-1, in patients with advanced solid malignancies (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02740985). The StaRs are sufficiently stable to be studied in biophysical experiments at room temperatures, including incorporation into HDL particles for biosensor studies [40] or covalently immobilization on gold surfaces or in a lipid bilayer for measuring binding using surface plasmon resonance [41]. StaRs may also be used for NMR studies, specifically target-immobilized NMR screening (TINS) for fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) of very small molecules that bind to the A2AAR with relatively low affinity [42]. These biophysical techniques have been useful in the discovery of new A2AAR ligands, despite the presence of mutations in the receptor. Other A2AAR antagonists are being developed for treating Parkinson’s disease (PD) [16].

An advanced crystallographic technique that was recently applied to the A2AAR in the absence of bound ligand is native phasing of X-ray data determined with a pulsed free-electron laser (XFEL) [43]. The data is collected using serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) using microcrystals that are delivered in a continuous hydrated stream and subsequently destroyed by the beam.

The conformational differences between the multiple agonist-bound and antagonist-bound structures of the A2AAR presents a consistent picture of the reorganization of the orthosteric site to accommodate nucleosides [17,18]. Furthermore, the predicted binding of nucleosides that vary greatly in efficacy at the A3AR, particularly after ribose modification [44,45], provides insights into residues implicated in the activation process.

We have collaborated with Ray Stevens and colleagues in the structural characterization of an agonist-bound A2AAR structure, antagonist-bound P2Y1R structures as well as agonist- and antagonist-bound P2Y12R structures containing stabilizing fusion proteins in the third intracellular loop (IL3) or at the N-terminus [17,20–22]. The receptor constructs contain few if any mutations in the TM regions, so they tend to preserve the native structures.

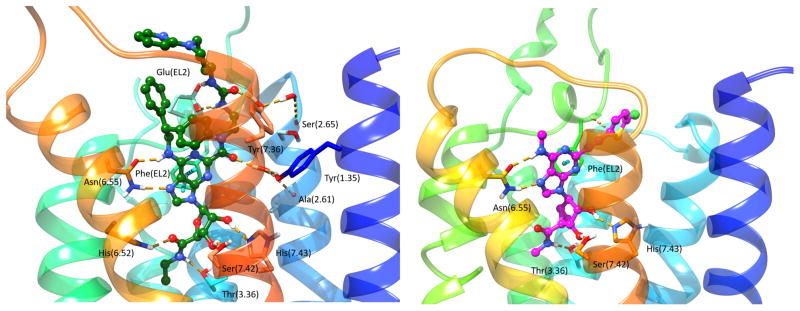

This first X-ray structure of an agonist-bound A2AAR used a bulky adenosine agonist with extended C2 and N6 groups on the adenine moiety (UK432097, 6-(2,2-diphenylethylamino)-9-((2R,3R,4S,5S)-5-(ethylcarbamoyl)-3,4-dihydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-N-(2-(3-(1-(pyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)ureido)ethyl)-9H-purine-2-carboxamide, 4) [17]. This substituent combination on the adenine and ribose moieties sufficiently stabilized the receptor complex as indicated by a rise in Tm (melting temperature). The 4-A2AAR structure and a subsequent report on structurally simpler agonists, 1 and 3, bound to A2AAR StaRs [18,46] feature a deep hydrophilic pocket. This forms the ribose moiety’s binding site, while the upper regions of the binding site where the nucleobase resides are largely surrounded by hydrophobic residues (Figure 2B). The hydrophobic regions accommodate the adenine moiety and its typically bulky hydrophobic substituents at the C2 and N6 positions (Figure 2B and Figure 3 left).

Figure 3.

High-resolution X-ray crystallographic structure of the hA2AAR with high affinity agonist UK432097 (4) bound (left, green carbon atoms) [17], and comparison with a hybrid homology model of the hA3AR with potent C2-arylethynyl agonist MRS5980 (8) bound (right, magenta carbon atoms) [79].

Among the interactions that stabilize the bound nucleobase is a π-π interaction between Phe168 (EL2) and the heterocyclic ring, which is conserved for diverse AR ligands (Figure 2B). However, the adenine moiety also has polar interactions with the A2AAR; similar to the coordination of ZM241385, the side chain of conserved Asn6.55 is H-bonded to both the adenine exocyclic secondary amine and N7. The various adenine substitutions, particularly at C2 and N6 positions, are often responsible for the subtype selectivity of the nucleosides, and the ribose with its multiple H-bonding groups is required for AR activation. His7.43 acts as an H-bond donor to the ribose 2′-hydroxyl group (Figure 2B). The latter interaction and the proximity of the A2AAR residue Thr3.36 to the ribose moiety of bound agonists were determined earlier using a neoceptor approach, which is based on complementary structural changes of the ligand and its targeted receptor [47,48], having now been confirmed in the X-ray structures. Both of these residues and the residues coordinating the adenine ring have identical or homologous functionality among the ARs. Thus, there is much conservation of the recognition pattern for agonists across the AR family.

However, there are some differences in interactions of nucleoside ligands between the A2AAR and A3AR that account for pharmacological differences of such ligands, with respect to their affinity, selectivity and efficacy. For example, His6.52 in A2AAR, which H-bonds to the 5′-carbonyl group of NECA 3 (Figure 2B) is replaced with Ser6.52 and is not in direct contact with docked nucleosides in the A3AR. The role of Thr3.36 in A2AAR, which H-bonds to the 5′-amide NH group of NECA, is maintained in the A3AR. The chemical “removal” of this NH, by alkylation or truncation of the amide, leads to A3AR nucleoside antagonists, possibly suggesting a role for TM3 in A3AR activation [17,49]. Some water molecules deep in the binding site of the antagonist-bound A2AAR are displaced by the ribose moiety of agonists when bound, which contributes to the favorable energetics of agonist binding. Unlike various other GPCRs, the native agonist binds to the several subtypes (except A2BAR) with near nanomolar affinity. AR activation by agonists is thought to involve a side chain rotation of Trp6.48, which, however, has not been captured in the X-ray structures [18,49,50]. The agonist-bound and agonist-bound A2AAR structures, including the surrounding membrane, were subjected to unbiased molecular dynamics and metadynamics simulations to predict conformational transitions upon activation, including rotamers of Trp6.48 [51].

In general the ribose or ribose-like moiety of adenosine is involved in AR activation and increase affinity at the four ARs, and the substituted adenine moiety mainly determines the subtype selectivity. These two domains – hydrophilic for ribose and hydrophobic for adenine were recognized even in early AR modeling based on rhodopsin [52]. This suggests that the binding site of adenosine derivatives in the ARs can ben divided into separate functional domains: ribose as the message (facilitating the receptor activation) moiety and adenine (directing the ligand to a receptor or receptor subtype) as the address moiety [31]. The same distinction has been applied to peptide GPCR ligands, i.e. they are conceptually divided into separate address and message sequences.

An engineered G protein segment (mini-Gs) was used to stabilize the A2AAR (NECA 3 complex) in an active-like state [49]. The observed conformational changes associated with binding of the mini-Gs as a GDP complex were similar to but not identical to those observed for the β2 adrenergic receptor active state, which was stabilized by a nanobody mimic of Gs protein. The most dramatic change in the overall structure in the NECA-A2AAR-mini-Gs complex was a shift of the cytoplasmic end of TM6 away from the receptor core by 14 Å with respect to the inactive state, with only slight changes for TMs 5 and 7. Furthermore, TMs 3, 5 and 7 underwent rotations. Thus, in the earlier active-intermediate state with only bound agonist UK432097 4, the conformational changes in the overall receptor structure, with respect to the cytosolic side, were underestimated [17]; in opsin, the corresponding outward movement of TM6 was 6–7 Å.

Most of the above approaches help define the recognition of ligands in the orthosteric binding site. In addition, allosteric modulators are well-explored for A1AR and A3AR, but the case for A2AAR remains unresolved [53]. Bitopic ligands of the A1AR that bridge the allosteric and orthosteric binding site have been reported. At the A2AAR, a bitopic antagonist 26, which additionally antagonizes the N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subtype 2B, was cocrystallized with the hA2AAR and shown to access the orthosteric site as well as a distal binding region on A2AAR (potentially an allosteric site) [54]. This defined a previously uncharacterized binding pocket of the A2AAR that could be exploited for allosteric modulation. Antagonizing both A2AAR and NMDA2BRwith a single compound might be a fruitful approach to treating PD.

Until recently, the A2AAR was the only AR with a structure determined. However, a recent report featured the A1AR structure in complex with an irreversibly bound antagonist DU172 (12b) [24]. The ligand’s reactive fluorosulfonyl group was linked to the hydroxyl group of Tyr7.36. The extracellular cavity was more exposed than in the A1AR due to a distinct conformation of EL2, and a secondary binding pocket suggests that it could accommodate both orthosteric and allosteric ligands.

2.1.2. X-ray structures of the P2Y1R and P2Y12R

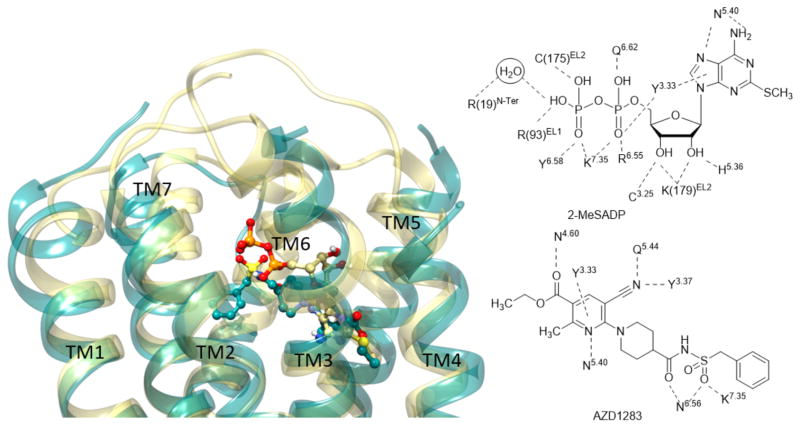

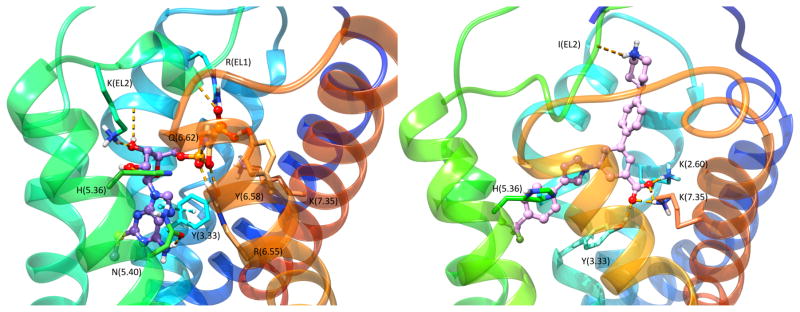

Unlike AR molecular modeling, early P2YR molecular modeling based on the structure of bovine rhodopsin and other templates was less successful in predicting the position and key interactions of agonists and antagonists [55]. Ligands that have been co-crystallized in P2YR X-ray structures include both agonists and antagonists (Figure 1B). The subsequent P2Y1 and P2Y12R X-ray structures [20–22], representing each of the two P2YR subfamilies, brought many surprises, i.e. features that were unlike any GPCR structures previously determined (Figures 3 and 4). Comparison of agonist-bound and antagonist-bound P2Y12R indicates unprecedented structural plasticity in the outer TM portions and the extracellular loops (Figure 4). There is a major difference in conformation needed to bind nonnucleotide antagonists (AZD1283, ethyl 6-(4-((benzylsulfonyl)carbamoyl)piperidin-1-yl)-5-cyano-2-methylnicotinate, 35) [56] and nucleotide partial agonists (such as 2-methylthio-ATP, 2-MeSATP 29) [20,21]. One of the most unusual features of the AZD1283-P2Y12R complex is the apparent lack of a disulfide bridge between EL2 and TM3 (otherwise conserved), but the presence of a disulfide between EL3 and the N-terminus (conserved for P2YRs). The outer TM portions and the ELs are also rich in positively charged Lys and Arg residues. Consequently, these residues close around the nucleotide ligands in both complexes with 2-methylthio-ADP (full agonist, 28) and 2-methylthio-ATP, and the conserved disulfide bridge (TM3 to EL3) is present. The variation in the presence of this disulfide bond between different complexes suggests that this bond is dynamic in the P2Y12R.

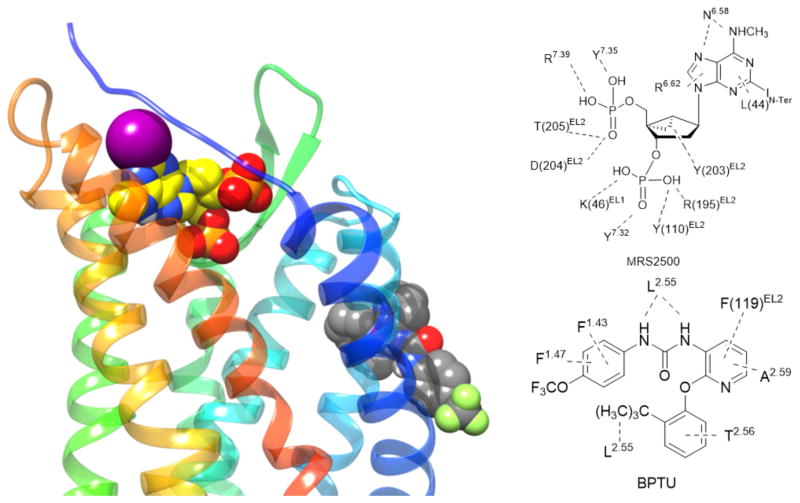

Figure 4.

Left panel: High-resolution X-ray crystallographic structures [22] of the hP2Y1R showing the binding sites for orthosteric antagonist MRS2500 (31) (yellow carbon atoms) and allosteric antagonist (NAM) BPTU (34) (grey carbon atoms). Right panel: Contacts between two co-crystallized ligands and the hP2Y1R.

Although P2Y1R, like P2Y12R, is activated by ADP, it belongs to a structurally distinct subset of the rhodopsin-like GPCR δ-branch. Structural comparison of the P2Y1R with bound nucleotide (orthosteric) and nonnucleotide (allosteric) antagonist indicates that a completely different residue sets are involved, i.e. no amino acids were shared by the two sites (Figure 5) [22]. The orthosteric nucleotide antagonist MRS2500 31 binds at a location involving the ELs that is more external than most small molecule orthosteric ligands of other GPCRs. Positively charged EL residues coordinate the phosphate groups at the 5′ and 3′-positions of the bisphosphate antagonist (Figure 5). The overall effect of bound MRS2500 31 is to constrain two receptor domains, i.e. TM1–TM4 and TM5–TM7, which would be expected to have a relative movement during activation. The negative allosteric modulator BPTU (1-(2-(2-(tert-butyl)phenoxy)pyridin-3-yl)-3-(4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl)urea, 34) [57] surprisingly bound to the outer P2Y1R surface in contact with the hydrophobic phospholipid membrane components and with residues in TMs 1–3. The binding site was shallow with the urea group of BPTU forming H-bonds with a TM2 backbone carbonyl group (Figure 5). The placement of this allosteric antagonist would constrain relative TM3 movement with respect to TM2, which is also characteristic of GPCR activation [17]. The mechanism for propagation of the conformational effects of 34 binding to other P2Y1R regions might involve the characteristic interactions of conserved hydrophobic and aromatic residues in TMs 3, 5 and 6 of various GPCRs [58]. The molecular recognition of other negative P2Y1R allosteric modulators can be modeled and is shown to be consistent with SAR data [22]. Curiously, the P2Y1R conformations present in complexes with the allosteric and the orthosteric antagonists are nearly identical, and no agonist-bound structure is yet reported.

Figure 5.

Left panel: Superimposition between X-ray crystallographic structures of the hP2Y12R in complex with 2-MeSADP (28) (yellow ribbon representation for the receptor and yellow carbon atoms for the ligand) [21] and AZD1283 (35) (dark cyan ribbon representation for the receptor and dark cyan carbon atoms for the ligand) [20]. Right panel: Contacts between two co-crystallized ligands and the hP2Y12R.

3. Methods

3.1. Structure-based medicinal chemistry of the ARs

Early molecular modeling and site-directed mutagenesis of the ARs based on the bovine rhodopsin structure was relatively successful in predicting the position of agonists and antagonists in the orthosteric binding site and their interacting residues, as was subsequently validated in the X-ray structures of antagonist-bound and later agonist-bound A2AARs. The ARs are members of Family A rhodopsin-like GPCRs, which is very close in overall structure to rhodopsin itself, although the sequence homology is low. Consequently, AR molecular modeling based on a rhodopsin template gave favorable results prior to and during the initial A2AAR structural determination [31,48,50,59]. The binding mode of nucleosides observed in the agonist-bound A2AAR structures was generalized to be consistent with the SAR of other known ligands, leading to their structural modification guided by predicted favorable interactions with the receptor [60].

3.1.1. Medicinal chemistry of the A2AAR

The A2AAR structures have been utilized for virtual screening (VS) campaigns to discover novel chemotypes that bind to the ARs [61–65] and to modify known ligands [65–67]. Previous efforts to model GPCR ligands were focused on an overlay of common structures in different ligands to generate a pharmacophore hypothesis of the molecular features needed for binding [68], and these hypotheses often did not take into account the receptor structure. Docking of 751 known antagonists in the A2AAR structure to create a refined pharmacophore model improved the predictive ability of subsequent quantitative SAR statistical models [69]. The pharmacophore hypothesis was validated with new test set of 29 A2AAR antagonists related to ZM241385 13.

Kinetic parameters of binding, as well as affinity, may be studied using modeling approaches. The dissociation kinetics of antagonists derived from ZM241385, i.e. 16 – 19, has been studied by X-ray crystallography of A2AAR StaRs [70]. A salt bridge involving EL residues of the A2AAR controlled the antagonist dissociation kinetics of analogues that had chemical modifications at the terminal phenol, as is present in ZM241385. Metadynamics investigations revealed that the salt bridge was readily broken in the simulations for ligands exhibiting short residence times, whereas it was maintained for ligands with longer residence times. X-ray structures of the ligand-receptor complexes highlighted that long residence time ligands established stabilizing interactions with His264 (EL3) that were not detected instead for ligands with shorter residence times.

The EL structure of a given GPCR is not only important for ligand affinity and binding kinetics, but can be utilized as the site of covalent modification by reactive, bitopic ligands. A2AAR agonists that modify the receptor irreversibly by acylating a specific residue, Lys153, in EL2 were designed through docking to the agonist-bound receptor structure [71]. The terminal position of the C2 chain contained a chemically reactive group, i.e. an active ester, and its proximity to Lys153 (EL3) facilitated this covalent modification of the receptor. A2AAR structures have guided the design of A3AR agonists and antagonists as well.

3.1.2. Medicinal chemistry of the A3AR

Originally, it was thought that A3AR antagonists might have broader application in the clinic than agonists, because of proinflammatory effects associated with acute agonist administration [73]. A3AR antagonists have been proposed for treatment of glaucoma or kidney fibrosis [73,76,77]. However, it is now recognized that A3AR agonists have shown efficacy in various animal models of inflammatory disease, cancer and chronic neuropathic pain [72–74]. Thus, the improvement of the affinity and selectivity of A3AR agonists has clear clinical relevance. Furthermore, prototypical agonists IB-MECA 5 and Cl-IB-MECA 6 have demonstrated safety and efficacy in Phase 2 and 1/2 clinical trials, respectively, and are now progressing to more advances trials in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, hepatocellular carcinoma and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [72,73].

The three-dimensional GPCR structures and related homology models have been used for improving the affinity and selectivity of known ligands as needed. For example, the design of A3AR agonists has benefited from iterative cycles of ligand docking to A3AR homology models followed by synthesis of new ligand analogues and model refinement. Differences between the structures of the AR subtypes are identified in the modeling process and can be used advantageously to increase selectivity.

The ribose moiety is the core of AR agonists that establishes the spatial relationship of important ligand recognition elements. We have substituted ribose in A3AR agonists with a variety of sterically constrained, bicyclic rings, to mimic the conformation of native tetrahydrofuryl ring of ribose when bound to the receptor. In particular, novel A3AR agonists are being refined, based on a highly rigidified (N)-methanocarba (a [3.1.0]bicyclohexane) scaffold, with computational approaches based on A2AAR X-ray structures as essential components, leading to nM binding affinities, exceptionally high selectivities and improved in vivo efficacy [13]. For example, MRS5698 7 is one such selective agonist that maintains consistent affinity across species (Ki = 3 nM at hA3AR and mouse A3AR). A hybrid A3AR model, based on the active or active-like structures of different GPCRs, was found most suitable for these new agonists [13]. High specificity (~10,000 fold selectivity for the A3AR) and clean ADME-tox and off-target properties were achieved.

In addition to the ongoing clinical trials of A3AR agonists for cancer and inflammation, they also have potential in pain treatment [74]. Novel A3AR agonists for pain control were designed and screened using an in vivo phenotypic model, which reflected both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. This close coupling of structure-based ligand design and in vivo testing permitted multiple parameters to be enhanced during the choice of synthetic target molecules. Activation of the A3AR in peripheral neurons, spinal cord and brain by highly specific C2-arylalkynyl agonists, e.g. MRS5980 8, as well as less selective A3AR agonists was found to reduce chronic neuropathic pain in vivo. This protection was dependent on GABAA receptor modulation, oxidative pathways, astrocytic activation, and cytokine levels in the spinal cord.

Although the AR binding site has two domains for ribose and adenine, there are examples of compensation for the loss of an otherwise important recognition element in one domain by features of a different domain of the ligand. For 4′-truncated A1AR agonists, a particular N6-dicyclopropylmethyl bound precisely in two subpockets of the N6 region to compensate for the absence of receptor binding stabilization at the 5′ position and activated the receptor [78]. In the MRS5980 8 chemical series of A3AR agonists, the N6 methylamino group could be group truncated to H or substituted with CH3 with retention of high affinity [79]. Thus, the exocyclic amine of adenosine derivatives was not essential for high affinity and selectivity at the A3AR, although the Asn6.55 side chain in A3AR models is similar to its position with more conventional agonists docked (Figure 3) [79]. The other stabilizing groups on these truncated analogues of MRS5980, e.g. at 5′ and C2, could partly compensate for the lack of H-bond stabilization between the exocyclic amine and this residue.

Biased agonists for a given GPCR display a preference for one or more signaling pathways [80,81], and such action has been explored for AR agonists. Biased agonism is based on the concept that a GPCR active state is associated with multiple conformations, and different activated conformations a given GPCR depend on which agonist is bound. More importantly, each conformation in theory has its own profile of preferred signaling, such as G-protein dependent vs. arrestin-dependent signaling. This is based on a particular receptor conformation resulting from agonist binding that is more effective in the preferred pathway compared to others. Biased A3AR agonism was detected in (N)-methanocarba analogues [82]. Conformational plasticity of the A3AR, especially with respect to the orientation of TM2, was proposed to accommodate bulky groups and correlate with signaling bias within this agonist class. Within a set of rigid C2-arylalkynyl and C2-polyarylalkynyl derivatives, the degree of bias for A3AR-dependent cell survival was directly proportional to the length of this substituent on the agonist. Hypothetically, this bias would correspond to the degree of outward displacement of the upper TM2 portion in the A3AR agonist-bound state. Thus, conformational A3AR plasticity was proposed to accommodate bulky groups and correlate with signaling bias within this class of agonists. However, it is to be noted that nucleoside A3AR antagonists with extended C2 substituents would also require TM2 displacement in the inactive receptor state [76]. Consistent with the prediction of an outward movement of TM2 to accommodate known A3AR ligands, the recently-determined structure of an antagonist-bound A1AR features TM2 displaced in the same direction by ~5 Å [24], relative to the A2AAR structure. Like the A3AR, the A1AR has only one disulfide bridge in the EL region; thus, TM2 is not constrained as in the A2AAR.

3.1.3. Virtual screening to discover AR ligands in general

In silico screening of diverse chemical libraries has identified numerous novel chemotypes for GPCR modulation. In silico screening has identified chemically diverse ligands at each of the AR subtypes. This structure-based drug design approach has been applied using the A2AAR X-ray structures resulting in typical hit rates of up to 40% with Ki values ≤ 10 μM [61,64,65]. In many cases, the hits displayed not only A2AAR affinity but also affinity at the closely related A1AR and/or A3AR. Thus, VS is a means of discovering novel chemotypes for binding to other AR family members because of the close structural homology.

Furthermore, nearly all of the hit molecules in VS of ARs were found to be AR antagonists, using as a template either an antagonist-bound A2AAR structure (as expected) or an agonist-bound structure (unexpected) [61,62,64]. This illustrated the close structural tolerance needed for AR activation and that nonribosides were highly unlikely to be suitable. Instead, the challenge of discovering novel agonists for the AR family was approached by screening within a set of ~7000 diverse nucleobases available commercially [65]. The screening was accomplished by first virtually attaching the ribose moiety before docking in an agonist-bound A2AAR structure – and finally by chemically synthesizing the ribosides from the nucleobase hits. In this manner, the pool of candidate molecules in the database was greatly expanded. Because the number of pre-formed ribosides in the databases was quite limited, the resulting hit rate for riboside products that activated one or more AR subtypes was greatly enhanced.

Modeling approaches have also facilitated the design of tool compounds for drug discovery, such as high affinity fluorescent ligands. Selective fluorescent agonist and antagonist probes of the A3AR have been reported [83]. For example, agonist MRS5218 (structure not shown) binds to the A3AR with high affinity (Ki 17 nM). The fluorophore (AlexaFluor488), attached through a functionalized alkynyl chain at C2, is thought to participate in the recognition when bound to the receptor’s outer loop region. Thus, the same functionalized AR ligand can vary enormously in affinity, with both increases and decreases with respect to the parent ligand. The affinity can depend strongly on the nature of the tethered fluorophore, because this moiety can contribute to the affinity by interacting with the receptor’s EL region.

Agonist discovery at other AR subtypes has also benefited from the high resolution A2AAR structures, in some cases unexpectedly through lateral hits. The structure-guided chemical modification of AR agonists at the adenosine 5′-amide position resulted in an oxetane derivative 9 that achieved high affinity at the A1AR instead of the A2AAR, and this gain of function was interpreted in terms of a different A1AR geometry in the ribose region that allowed H-bonding of conserved Asn5.42 to the oxetane ether [66]. The bulky presence of the Trp5.46 side chain in A1AR, compared to Cys5.42 in A2AAR, creates a cavity for the oxetane ring to lodge between TM5 and TMs 3 and 4. The binding region of the A1AR around the N6 group was predicted to accommodate two hydrophobic groups, e.g. dicyclopropyl, consistent with the previously explored recognition of α-branched substituents demonstrating a diastereomeric preference [78].

Ligand docking at an A2BAR homology model based on an antagonist-bound A2AAR structure has aided the design of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones, such as 20 (Ki hA2BAR = 3.49 nM), as novel antagonist chemotypes that display high selectivity [84]. Compounds 21 and 24 arose from A2AAR screens and were found to bind selectively to the A1AR [61,85]. Compounds 22 and 23 were identified in a screen using A1AR homology models and bound selectively to the A3AR [64]. Compound 25 was identified using the agonist-bound A2AAR, but was found to be a mixed antagonist at the A1AR and A2AAR [86]. Thus, there is considerable activity of screening hits at related receptors. In silico screening and structure-based design strategies have also led to the identification of nonnucleoside atypical partial agonists of the ARs based on a 7-prolinol-thiazolo[5,4-d]-pyrimidine scaffold [87]. 2-Amino-3-cyanopyridines appeared as hits in VS based on agonist-bound A2AARs, but they were AR antagonists [86], unlike related 2-amino-3,5-dicyanopyridines that act as atypical AR agonists [88]. Docking studies helped in rationalizing the binding of these compounds at the A2AAR and in identifying surrogates for the ribose ring that afforded receptor activation. Indeed, a 2-furylmethanol moiety in the 2-amino-3-cyanopyridine series was predicted to establish H-bond interaction with Ser(7.42), whereas the 2-hydroxylmethyl pyrrolidine moiety in the 7-prolinol-thiazolo[5,4-d]-pyrimidine series was predicted to establish H-bond interaction with His(7.43).

3.1.4. A3AR allosteric modulators

Nearly all of the AR X-ray structures reported contained orthosteric ligands, but modeling has been applied to the binding of allosteric ligands as well. Several classes of nitrogen heterocyclic molecules have been shown to be positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) for the A3AR, but no X-ray structures to firmly establish their binding site on the receptor. One such allosteric enhancer is N-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-2-cyclohexyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine (LUF6000, 10). Nevertheless, site-directed mutagenesis and modeling approaches, including Supervised Molecular Dynamics (SuMD), have attempted to determine the residues involved in their allosteric binding vs. the residues needed for orthosteric binding [89]. In the SuMD study, LUF6000 was found to engage in interactions with a putative meta-binding site located at the interface between EL2 and the upper region of TM5 and TM6, prior reaching the orthosteric site. A π-π stacking interaction established with Phe168 (EL2) triggered the allosteric modulator to reach the orthosteric binding site occupied by the agonist adenosine (1). In the final ternary complex, LUF6000 established hydrophobic contacts with residues in the upper region of the orthosteric binding site, thus acting as “pocket cap”.

3.2. Structure-based medicinal chemistry of the P2YRs

P2Y12R antagonists display potent anti-thrombotic activity by preventing the action of ADP on the platelet surface, which is the basis of blockbuster drugs such as clopidopgrel. P2Y1R antagonists, such as the orthosteric antagonist MRS2500 31 of nM affinity, also have potent anti-thrombotic activity by antagonizing ADP at platelet receptors, but this therapeutic concept has not yet resulted in clinical trials [90]. Thus, there is continuing interest in designing ligands of the ADP-activated P2Y1R and P2Y12R as antithrombotic agents and also to explore clinical potential of other P2YR ligands. Although there is not yet an X-ray structure for any of the other P2YRs, much insight can be gained from homology modeling, as we illustrate below for the P2Y14R. We have used P2YR structures to understand the recognition of numerous antagonists at these receptors [91,92].

3.2.1. Medicinal chemistry of the P2Y1R

Because there is no agonist-bound P2Y1R structure, the extension of the P2YR structures to binding of diverse agonists is best justified for the P2Y12R. Nevertheless, a P2Y1R nucleotide agonist 2-MeSADP 28 was found to dock in a similar position, at least with respect to adenine and ribose moieties, as the nucleotide orthosteric antagonist 31. For allosteric antagonists, such as BPTU 34, the docking of other urea and related derivatives [15] that were reported to have the same antagonistic effect on P2Y1R explains some observed SAR in this series. These allosteric antagonists are predominantly hydrophobic molecules, consistent with the required passage through the phospholipid bilayer in order to reach the structurally defined binding site. Attempts to introduce polar groups while retaining P2Y1R affinity were only partially successful [93].

The environments surrounding the hydrophilic nucleotide MRS2500 31 binding site of the P2Y1R structure and the hydrophobic allosteric binding site have very different properties and would require separate treatment in VS. An in silico screen was performed using the MRS2500-P2Y1R structure to identify compounds from medicinal plants related to Chinese traditional medicines that might have potential as antithrombotic drugs [94].

3.2.2. Medicinal chemistry of the P2Y12R

The first step in extending the reported P2YR structures to novel ligands and subsequently to other P2YR subtypes was an effort to explain the known ligand SAR. Representative P2Y12R ligands from different chemical classes were docked in the structures [54]. The P2Y12R X-ray structures with nucleotides bound (2-MeSADP and the corresponding triphosphate) differ greatly in conformation from the complex with nonnucleotide antagonist AZD1283 35 bound (Figure 4). Therefore, the question arose as to which structure could best serve as a suitable template for modeling the binding of various known P2Y12R ligands. The nucleotide complex(es) were found to be a suitable template for various agonists and diverse antagonists, many of which contain negatively charged groups. These diverse anionic groups were predicted to interact with Lys7.35 – similar to its interaction with the partial negative charge of a sulfonyl oxygen of 35 in its P2Y12R complex (Figure 4). The binding of nucleotide Cangrelor 32, which is now an approved antithrombotic drug, was well accommodated in the same orientation as 2-MeSADP 28 in its P2Y12R complex (Figure 6 left). The adenine moiety forms π-π stacking with Tyr3.33, suggesting that nonaromatic nucleobase substitution is not possible at P2Y12R (Figure 4). Although bulkier than the corresponding substitutions in 28, the C2 and N6 substituents fit in small pockets delimited, respectively, by TMs 3, 4 and 5 and at the base of the binding site toward TM6. The binding of Ticagrelor 33, which was the first competitive P2Y12R antagonist [95] to be approved as an antithrombotic drug, required a P2Y12R hybrid model to accommodate the extended C2 and N6 groups. However, SuMD simulation did not predict the proposed position of 33 in the orthosteric binding site of P2Y12R [54].

Figure 6.

High-resolution X-ray crystallographic structures of the hP2Y12R with agonist 2-MeSADP (28) bound (purple carbon atoms, left), and comparison with a homology model of the hP2Y14R with potent nonnucleotide antagonist MRS4217 (37) bound (pink carbon atoms, right) [14].

3.2.3. Medicinal chemistry of the P2Y14R

The P2Y14R is activated by UDP-sugars and is the focus of structure-based ligand design studies. Homology modeling based on the closely related nucleotide-P2Y12R structure (with 45% sequence identity), docking and MD predicted the position of the nucleotide P2Y14R agonists [96]. The uridine moiety of UDP-glucose 30 is bound in the same region as the adenosine moiety of ADP 27a in the P2Y12R (Figure 6 left), and a similar analogy applies to the 5′-diphosphate moieties. The uracil ring is located in a smaller hydrophobic region of the binding site than the corresponding region in P2Y12R, which is consistent with this receptor’s strong preference for uracil nucleotides. The glucose moiety is predicted to bind in the second subpocket of the bifurcated orthosteric binding site of P2Y14R, which is present yet vacant in the P2Y12R. Because of its predicted position facing the ELs, this glucose moiety is amenable to structural modification without impairing receptor binding and is used as an attachment site to produce a high affinity fluorescent agonist of P2Y14R, MRS4183 (structure not shown) [96]. In that fluorescent analogue, a boron-dipyrromethene TR (BODIPY TR) fluorophore is coupled by amide linkage to the distal carboxylate of UDP-glucuronic acid. These new advances in understanding P2Y14R structure, based on P2Y12R X-ray structures and computational approaches, are now being applied to the synthesis of more drug-like antagonists. 4-(4-(Piperidin-4-yl)phenyl)-7-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-naphthoic acid (PPTN, 36) [97,98] is a naphthoic acid derivative that was determined to be highly potent and selective for the P2Y14R. PPTN was originally prepared by a pharmaceutical industrial laboratory based on a high throughput screening hit [97], and later demonstrated a high potency and selectivity for P2Y14R [98]. This compound has poor physical properties and low bioavailability, but was used as a lead compound for the structure-based design of novel antagonists in which the naphthalene moiety was substituted with less hydrophobic bioiosteres [14]. A computational pipeline was used to compare P2Y14R recognition of proposed analogues and led to the identification of 4′-(piperidin-4-yl)-5-(4-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid (MRS4217, 37), which was only 6-fold less potent than PPTN in a fluorescence-based binding assay in whole cells. Docking and MD simulation suggested that the compound was able to establish an H-bond network with Lys2.60, Lys7.35 and Tyr3.33 along with a π-π tacking interaction with His5.36 (Figure 6 right). These interactions were stably maintained during 30 ns of MD simulations.

Chemical tools for structural probing of these GPCRs and improving assay capabilities, such as fluorescent probes of the inflammation-related P2Y14R [96,99], were designed with the aid of docking and MD. This was especially important for drug discovery at the P2Y14R, because there are no high affinity radioligands. The high affinity fluorescent antagonist MRS4174 (structure not shown, Ki 0.08 nM) was designed as a PPTN analogue, in which a fluorophore (AlexaFluor488) is strategically tethered through alkylation of the piperidine ring’s amino group. The location of the functionalized chain was planned at this position based on a prediction from docking of the parent antagonist, which featured the piperidine moiety exposed to the extracellular medium. The affinity gain with respect to PPTN is predicted to be from polar interactions of the charged fluorophore moiety with specific amino acids of the P2Y14R ELs.

4. Notes

Recent breakthroughs in computational modeling approaches have impacted the medicinal chemistry aimed at discovering new ligands for adenosine and P2Y receptors. Purine receptor structures and an interdisciplinary approach have enabled the elucidation of their biological role, the conceptualization of future therapeutics and novel ligand discovery. Computational approaches based on A2AAR X-ray structures guided the identification and refinement of novel A3AR agonists for treating chronic neuropathic pain, on the basis of a highly rigidified (N)-methanocarba scaffold. Molecular docking and MD aided the design of fluorescent AR and P2Y14R probes as chemical tools for structural exploration of these GPCRs and for improving assay capabilities. Computational approaches based on P2Y12R structures guided the design of more drug-like antagonists of the inflammation-related P2Y14R. The molecular recognition of positive (for A3AR) and negative (P2Y1R) allosteric modulators has also been modeled to shed light on ARs and PYRs allosteric modulation. Thus, computational modeling based on physically determined structures is now an essential tool for GPCR ligand design.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the NIDDK, NIH Intramural Research Program.

References

- 1.Santos R, Ursu O, Gaulton A, et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;16:19–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason JS, Bortolato A, Weiss DR, et al. High end GPCR design: crafted ligand design and druggability analysis using protein structure, lipophilic hotspots and explicit water networks. Silico Pharmacol. 2013;1:23. doi: 10.1186/2193-9616-1-23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tautermann CS. GPCR structures in drug design, emerging opportunities with new structures. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:4073–4079. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez D, Ranganathan A, Carlsson J. Discovery of GPCR Ligands by Molecular Docking Screening: Novel Opportunities Provided by Crystal Structures. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15:2484–2503. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150701112853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kooistra AJ, Vischer HF, McNaught-Flores D, et al. Function-specific virtual screening for GPCR ligands using a combined scoring method. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28288. doi: 10.1038/srep28288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnstock G. Short- and long-term (trophic) purinergic signalling. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016;371:20150422. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronstein BN, Sitkovsky M. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the pathogenesis and treatment of rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;13:41–51. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Sträter N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boison D. Adenosine Kinase: Exploitation for Therapeutic Gain. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:906–943. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.006361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schöneberg T, Hermsdorf T, Engemaier E, et al. Structural and functional evolution of the P2Y12-like receptor group. Purinergic Signal. 2007;3:255–268. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9064-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verkhratsky A, Burnstock G. Biology of purinergic signalling: Its ancient evolutionary roots, its omnipresence and its multiple functional significance. BioEssays. 2014;36:697–705. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toti KS, Osborne D, Ciancetta A, et al. South (S)- and North (N)-methanocarba-7-deazaadenosine analogues as inhibitors of human adenosine kinase. J Med Chem. 2016;59:6860–6877. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tosh DK, Deflorian F, Phan K, et al. Structure-guided design of A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides: Combination of 2-arylethynyl and bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane substitutions. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4847–4860. doi: 10.1021/jm300396n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junker A, Balasubramanian R, Ciancetta A, et al. Structure-based design of 3-(4-aryl-1 H -1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-biphenyl derivatives as P2Y14 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2016;59:6149–6168. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conroy S, Kindon N, Kellam B, Stocks MJ. Drug-like antagonists of P2Y receptors—from lead identification to drug development. J Med Chem. 2016;59:9981–10005. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaakola V-P, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, et al. The 2.6 Angstrom Crystal Structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu F, Wu H, Katritch V, et al. Structure of an agonist-bound human A2A adenosine receptor. Science. 2011;332:322–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1202793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebon G, Warne T, Edwards PC, et al. Agonist-bound adenosine A2A receptor structures reveal common features of GPCR activation. Nature. 2011;474:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Chun E, Thompson AA, et al. Structural basis for allosteric regulation of GPCRs by sodium ions. Science. 2012;337:232–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1219218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K, Zhang J, Gao Z-G, et al. Structure of the human P2Y12 receptor in complex with an antithrombotic drug. Nature. 2014;509:115–118. doi: 10.1038/nature13083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Zhang K, Gao Z-G, et al. Agonist-bound structure of the human P2Y12 receptor. Nature. 2014;509:119–122. doi: 10.1038/nature13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D, Gao Z-G, Zhang K, et al. Two disparate ligand-binding sites in the human P2Y1 receptor. Nature. 2015;520:317–321. doi: 10.1038/nature14287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jazayeri A, Andrews SP, Marshall FH. Structurally enabled discovery of adenosine A2A receptor antagonists. Chem Rev. 2017;117:21–37. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glukhova A, Thal DM, Nguyen AT, et al. Structure of the adenosine A1 receptor reveals the basis for subtype selectivity. Cell. 2017;168:867–877. e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou Y, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. N-Terminal T4 lysozyme fusion facilitates crystallization of a G protein coupled receptor. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katritch V, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure-function of the G protein–coupled receptor superfamily. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:531–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-032112-135923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steyaert J, Kobilka BK. Nanobody stabilization of G protein-coupled receptor conformational states. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warne T, Serrano-Vega MJ, Baker JG, et al. Structure of a β1-adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2008;454:486–491. doi: 10.1038/nature07101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh E, Kumari P, Jaiman D, Shukla AK. Methodological advances: the unsung heroes of the GPCR structural revolution. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:69–81. doi: 10.1038/nrm3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doré AS, Robertson N, Errey JC, et al. Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure. 2011;19:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivanov AA, Barak D, Jacobson KA. Evaluation of homology modeling of G-protein-coupled receptors in light of the A2A adenosine receptor crystallographic structure. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3284–3292. doi: 10.1021/jm801533x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobson KA. Functionalized congener approach to the design of ligands for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1816–1835. doi: 10.1021/bc9000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Methods Neurosci. Elsevier; 1995. [19] Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors; pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massink A, Louvel J, Adlere I, et al. 5′-Substituted Amiloride Derivatives as Allosteric Modulators Binding in the Sodium Ion Pocket of the Adenosine A2A Receptor. J Med Chem. 2016;59:4769–4777. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgs C, Beuming T, Sherman W. Hydration site thermodynamics explain SARs for triazolylpurines analogues binding to the A2A receptor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2010;1:160–164. doi: 10.1021/ml100008s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenselink EB, Beuming T, Sherman W, et al. Selecting an optimal number of binding site waters to improve virtual screening enrichments against the adenosine A2A receptor. J Chem Inf Model. 2014;54:1737–1746. doi: 10.1021/ci5000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magnani F, Serrano-Vega MJ, Shibata Y, et al. A mutagenesis and screening strategy to generate optimally thermostabilized membrane proteins for structural studies. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:1554–1571. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langmead CJ, Andrews SP, Congreve M, et al. Identification of novel adenosine A2A receptor antagonists by virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1904–1909. doi: 10.1021/jm201455y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gutiérrez-de-Terán H, Sallander J, Sotelo E. Structure-based rational design of adenosine receptor ligands. Curr Top Med Chem. 2017;17:40–58. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160719164207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segala E, Errey JC, Fiez-Vandal C, et al. Biosensor-based affinities and binding kinetics of small molecule antagonists to the adenosine A2A receptor reconstituted in HDL like particles. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1399–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bocquet N, Kohler J, Hug MN, et al. Real-time monitoring of binding events on a thermostabilized human A2A receptor embedded in a lipid bilayer by surface plasmon resonance. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2015;1848:1224–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen D, Errey JC, Heitman LH, et al. Fragment screening of GPCRs using biophysical methods: Identification of ligands of the adenosine A2A receptor with novel biological activity. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:2064–2073. doi: 10.1021/cb300436c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Batyuk A, Galli L, Ishchenko A, et al. Native phasing of x-ray free-electron laser data for a G protein-coupled receptor. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600292–e1600292. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao ZG, Kim SK, Biadatti T, et al. Structural determinants of A3 adenosine receptor activation: Nucleoside ligands at the agonist/antagonist boundary. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4471–4484. doi: 10.1021/jm020211+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toti KS, Moss SM, Paoletta S, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of N6-substituted apioadenosines as potential adenosine A3 receptor modulators. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22:4257–4268. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lebon G, Edwards PC, Leslie AGW, Tate CG. Molecular determinants of CGS21680 binding to the human adenosine A2A receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87:907–915. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.097360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao Z-G, Duong HT, Sonina T, et al. Orthogonal activation of the reengineered A3 adenosine receptor (neoceptor) using tailored nucleoside agonists. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2689–2702. doi: 10.1021/jm050968b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobson KA, Ohno M, Duong HT, et al. A neoceptor approach to unraveling Microscopic interactions between the human A2A adenosine receptor and its agonists. Chem Biol. 2005;12:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carpenter B, Nehmé R, Warne T, et al. Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an engineered G protein. Nature. 2016;536:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature18966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim S-K, Gao Z-G, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Docking studies of agonists and antagonists suggest an activation pathway of the A3 adenosine receptor. J Mol Graph Model. 2006;25:562–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, Jonsson AL, Beuming T, Shelley JC, Voth GA. Ligand-Dependent Activation and Deactivation of the Human Adenosine A2A Receptor. J Am Chem Soc. 2103;135:8749–8759. doi: 10.1021/ja404391q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JH, Wess J, van Rhee AM, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis identifies residues involved in ligand recognition in the human A2a adenosine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13987–13997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Allosteric modulators of adenosine, P2Y and P2X receptors. In: Doller D, editor. Chapter 11 in Allosterism in Drug Discovery. 2017. pp. 247–270. (RSC Drug Discovery Series No. 56) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun B, Bachhawat P, Chu MLH, et al. Crystal structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an antagonist reveals a potential allosteric pocket. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:2066–2071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621423114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paoletta S, Sabbadin D, von Kügelgen I, et al. Modeling ligand recognition at the P2Y12 receptor in light of X-ray structural information. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2015;29:737–756. doi: 10.1007/s10822-015-9858-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bach P, Boström J, Brickmann K, et al. Synthesis, structure–property relationships and pharmacokinetic evaluation of ethyl 6-aminonicotinate sulfonylureas as antagonists of the P2Y12 receptor. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;65:360–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chao H, Turdi H, Herpin TF, et al. Discovery of 2-(Phenoxypyridine)-3-phenylureas as small molecule P2Y1 antagonists. J Med Chem. 2013;56:1704–1714. doi: 10.1021/jm301708u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenbaum DM, Zhang C, Lyons JA, et al. Structure and function of an irreversible agonist-β2 adrenoceptor complex. Nature. 2011;469:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim S-K, Jacobson KA. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship of nucleosides acting at the A3 adenosine receptor: Analysis of binding and relative efficacy. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:1225–1233. doi: 10.1021/ci600501z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deflorian F, Kumar TS, Phan K, et al. Evaluation of molecular modeling of agonist binding in light of the crystallographic structure of an agonist-bound A2A adenosine receptor. J Med Chem. 2012;55:538–552. doi: 10.1021/jm201461q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katritch V, Jaakola V-P, Lane JR, et al. Structure-based discovery of novel chemotypes for adenosine A2A receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2010;53:1799–1809. doi: 10.1021/jm901647p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carlsson J, Yoo L, Gao Z-G, et al. Structure-based discovery of A2A adenosine receptor ligands. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3748–3755. doi: 10.1021/jm100240h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Congreve M, Andrews SP, Doré AS, et al. Discovery of 1,2,4-triazine derivatives as adenosine A2A antagonists using structure based drug design. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1898–1903. doi: 10.1021/jm201376w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kolb P, Phan K, Gao Z-G, et al. Limits of ligand selectivity from docking to models: in silico screening for A1 adenosine receptor antagonists. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodríguez D, Chakraborty S, Warnick E, et al. Structure-based screening of uncharted chemical space for atypical adenosine receptor agonists. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:2763–2772. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tosh DK, Phan K, Gao Z-G, et al. Optimization of adenosine 5′-carboxamide derivatives as adenosine receptor agonists using structure-based ligand design and fragment screening. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4297–4308. doi: 10.1021/jm300095s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paoletta S, Tosh DK, Finley A, et al. Rational design of sulfonated A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides as pharmacological tools to study chronic neuropathic pain. J Med Chem. 2013;56:5949–5963. doi: 10.1021/jm4007966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jacobson KA, Costanzi S, Paoletta S. Computational studies to predict or explain G protein-coupled receptor polypharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bacilieri M, Ciancetta A, Paoletta S, et al. Revisiting a receptor-based pharmacophore hypothesis for human A2A adenosine receptor antagonists. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:1620–1637. doi: 10.1021/ci300615u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Segala E, Guo D, Cheng RKY, et al. Controlling the dissociation of ligands from the adenosine A2A receptor through modulation of salt bridge strength. J Med Chem. 2016;59:6470–6479. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moss SM, Jayasekara PS, Paoletta S, et al. Structure-based design of reactive nucleosides for site-specific modification of the A2A adenosine receptor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5:1043–1048. doi: 10.1021/ml5002486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fishman P, Bar-Yehuda S, Liang BT, Jacobson KA. Pharmacological and therapeutic effects of A3 adenosine receptor agonists. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Borea PA, Varani K, Vincenzi F, et al. The A3 adenosine receptor: History and perspectives. Pharmacol Rev. 2014;67:74–102. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.008540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Janes K, Symons-Liguori A, Jacobson KA, Salvemini D. Identification of A3 adenosine receptor agonists as novel non-narcotic analgesics. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:1253–1267. doi: 10.1111/bph.13446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Katritch V, Fenalti G, Abola EE, et al. Allosteric sodium in class A GPCR signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tosh DK, Paoletta S, Phan K, et al. Truncated nucleosides as A3 adenosine receptor ligands: Combined 2-arylethynyl and bicyclohexane substitutions. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:596–601. doi: 10.1021/ml300107e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nayak A, Chandra G, Hwang I, et al. Synthesis and anti-renal fibrosis activity of conformationally locked truncated 2-hexynyl-N6-substituted-(N)-methanocarbanucleosides as A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1344–1354. doi: 10.1021/jm4015313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tosh DK, Paoletta S, Deflorian F, et al. Structural sweet spot for A1 adenosine receptor activation by truncated (N)-methanocarba nucleosides: receptor docking and potent anticonvulsant activity. J Med Chem. 2012;55:8075–8090. doi: 10.1021/jm300965a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tosh DK, Ciancetta A, Warnick E, et al. Purine (N)-methanocarba nucleoside derivatives lacking an exocyclic amine as selective A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2016;59:3249–3263. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strachan RT, Sun JP, Rominger DH, et al. Divergent transducer-specific molecular efficacies generate biased agonism at a G Protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14211–14224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.548131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Galandrin S, Onfroy L, Poirot MC, et al. Delineating biased ligand efficacy at 7TM receptors from an experimental perspective. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;77:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baltos J-A, Paoletta S, Nguyen ATN, et al. Structure-activity analysis of biased agonism at the human adenosine A3 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2016;90:12–22. doi: 10.1124/mol.116.103283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kozma E, Gizewski ET, Tosh DK, et al. Characterization by flow cytometry of fluorescent, selective agonist probes of the A3 adenosine receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1171–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.El Maatougui A, Azuaje J, González-Gómez M, et al. Discovery of potent and highly selective A2B adenosine receptor antagonist chemotypes. J Med Chem. 2016;59:1967–1983. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ranganathan A, Stoddart LA, Hill SJ, Carlsson J. Fragment-Based Discovery of Subtype-Selective Adenosine Receptor Ligands from Homology Models. J Med Chem. 2015;58:9578–9590. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rodríguez D, Gao Z-G, Moss SM, et al. Molecular docking screening using agonist-bound GPCR structures: Probing the A2A adenosine receptor. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:550–563. doi: 10.1021/ci500639g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bharate SB, Singh B, Kachler S, et al. Discovery of 7-(prolinol-N-yl)-2-phenylaminothiazolo[5,4-d]pyrimidines as novel non-nucleoside partial agonists for the A2A adenosine receptor: Prediction from molecular modeling. J Med Chem. 2016;59:5922–5928. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Louvel J, Guo D, Soethoudt M, et al. Structure-kinetics relationships of Capadenoson derivatives as adenosine A1 receptor agonists. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;101:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deganutti G, Cuzzolin A, Ciancetta A, Moro S. Understanding allosteric interactions in G protein-coupled receptors using Supervised Molecular Dynamics: A prototype study analysing the human A3 adenosine receptor positive allosteric modulator LUF6000. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:4065–4071. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wong PC, Watson C, Crain EJ. The P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS2500 prevents carotid artery thrombosis in cynomolgus monkeys. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:514–521. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Conroy S, Kindon N, Kellam B, Stocks MJ. Nucleotides acting at P2Y receptors: Connecting structure and function. J Med Chem. 2016;59:9981–10005. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jacobson KA, Paoletta S, Katritch V, et al. Nucleotides acting at P2Y receptors: Connecting structure and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;88:220–230. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.095711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hu CH, Qiao JX, Han Y, et al. 2-Amino-1,3,4-thiadiazoles in the 7-hydroxy-N-neopentyl spiropiperidine indolinyl series as potent P2Y1 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:2481–2485. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yi F, Sun L, Xu L-j, Peng Y, et al. In silico Approach for Anti Thrombosis Drug Discovery: P2Y1R Structure-Based TCMs Screening. Front Pharmacol. 2017;7:531. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hoffmann K, Lutz DA, Straßburger J, et al. Competitive mode and site of interaction of ticagrelor at the human platelet P2Y12 -receptor. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1898–1905. doi: 10.1111/jth.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kiselev E, Balasubramanian R, Uliassi E, et al. Design, synthesis, pharmacological characterization of a fluorescent agonist of the P2Y14 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:4733–4739. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gauthier JY, Belley M, Deschênes D, et al. The identification of 4,7-disubstituted naphthoic acid derivatives as UDP-competitive antagonists of P2Y14. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2836–2839. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barrett MO, Sesma JI, Ball CB, et al. A selective high-affinity antagonist of the P2Y14 receptor inhibits UDP-glucose-stimulated chemotaxis of human neutrophils. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:41–49. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.085654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kiselev E, Barrett MO, Katritch V, et al. Exploring a 2-naphthoic acid template for the structure-based design of P2Y14 receptor antagonist molecular probes. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:2833–2842. doi: 10.1021/cb500614p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hino T, Arakawa T, Iwanari H, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor inactivation by an allosteric inverse-agonist antibody. Nature. 2012;482:237–240. doi: 10.1038/nature10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]