Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that results in severe disability. Very few studies have explored changes in daily physical activity patterns during early stages of AD when components of physical function and mobility may be preserved.

Methods

Patients with mild AD and controls (n=92) recruited from the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center Registry, wore the Actigraph GT3X+ for seven days, and provided objective physical function (VO2 max) and mobility data. Using multivariate linear regression, we explored whether individuals with mild AD had different daily average and diurnal physical activity patterns compared to controls independent of non-cognitive factors that may affect physical activity, including physical function and mobility.

Results

We found that mild AD was associated with less moderate-intensity physical activity (p<0.05), lower peak activity (p<0.01), and lower physical activity complexity (p<0.05) particularly during the morning. Mild AD was not associated with greater sedentary activity or less lower-intensity physical activity across the day after adjusting for non-cognitive covariates.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that factors independent of physical capacity and mobility may drive declines in moderate-intensity physical activity, and not lower-intensity or sedentary activity, during the early stage of AD. This underscores the importance of a better mechanistic understanding of how cognitive decline and AD pathology impact physical activity. Findings emphasize the potential value of designing and testing time-of-day specific physical activity interventions targeting individuals in the early stages of AD, prior to significant declines in mobility and physical function.

Keywords: physical fitness, Alzheimer disease, motor activity, physical conditioning, physical exertion

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease associated with loss of cognitive and physical function. Although cognitive symptoms are primary, studies have shown that walking difficulties and motor dysfunction are also common [1, 2]. These mobility impairments may have a common cause with cognitive decline [3] and may be closely associated with neurodegeneration and AD pathology AD, including gray matter degeneration, white matter damage, and amyloid-beta accumulation [4, 5].

Physical activities, including activities of everyday living (ADLs), leisure-time activities, and exercise, are dependent on mobility and cognitive functioning [3]. While very few studies have explored changes in physical activity during the early stages of AD, gross motor function and certain domains of cognition [6] are largely preserved, suggesting that many daily physical activities may also be maintained [7]. As AD progresses from the mild stage to more moderate and severe stages, declines in cognition and physical function lead to a significant reduction in physical activities due to the inability to function independently [7] and severe disability [8].

In addition to functional declines, AD is also associated with a breakdown of the normal sleep-wake or rest-activity cycle [9]. Sleep disturbance, reduced quality of sleep, and increased daytime sleep are common in AD [10, 11], and worsen gradually with increasing disease severity [12]. These disturbances may significantly impact total physical activity as well as diurnal patterns of physical activity across the day. These changes may also reflect neurodegenerative processes, indicating potential targets for modification through intervention.

The mild stage of AD is critical for physical activity interventions that have the potential to slow the disease course [13], reduce functional dependence, and increase quality of life [14, 15]. Individuals with mild AD, compared to those with moderate and severe AD, may have the physical and cognitive capacity to engage in a broad range of activities, and may have more intact circadian rhythms. Thus, they are an important target group for interventions, including aerobic exercise [16] and multimodal interventions [17, 18] that have been shown to improve cognition and increase brain health.

Prior to testing these interventions, it is critical to better understand how physical activity may change due to mild AD when only subtle declines in physical function and mobility are observed [19, 20]. Very few studies have explored how mild AD may alter physical activity levels, and none have explored how physical activity patterns across the day are impacted. Considering changes in circadian rhythms due to AD, and the potential impact of those change on physical activity, it is critical to explore both daily average and diurnal patterns of activity, which may provide important insights for the design of tailored physical activity interventions.

We measured physical activity continuously for seven days using body-worn accelerometers in older adults with mild AD and cognitively normal older adult controls. We were interested in describing diurnal physical activity profiles among individuals with mild AD compared to controls to better understand how AD may affect physical activity in the earliest disease stage, independent of the effects of non-cognitive factors including physical function and age.

Materials and Methods

Study Sample

Participants were recruited from the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center Registry (KU-ADC), a large registry of well-characterized AD patients and older adult controls without cognitive impairment. KU-ADC recruitment and evaluation have been described previously [21]. Registry participants receive cognitive testing and clinical examinations annually. Experienced study clinicians trained in dementia assessment and clinical research provide consensus diagnoses through a comprehensive clinical research evaluation and review of medical records. Diagnostic criteria for AD follow NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [22].

Participants who had undergone full physical and neurological examinations and a review of medical history were recruited into this study. The study sample included individuals with mild AD based on a clinical dementia rating (CDR; [23]) scale scores of 0.5 (very mild) or 1 (mild) or older adult controls with CDR scores of 0 (normal). Participants with AD were required to have a study partner who spends at least 10 hours per week with the participant, who would be with the participant every day during the data collection procedures (detailed below). Participants with mobility disability, including those confined to a bed or wheel chair, as well as participants with sensory impairment, including those with inadequate visual or auditory capacity were excluded. The KU-ADC registry excludes individuals with active (<2 years) ischemic heart disease (myocardial infarction or symptoms of coronary artery disease) or uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes mellitus.

A total of 100 community dwelling older adults with and without mild AD were recruited. Of those, N=92 had valid actigraphy data (n = 39 mild AD; n = 53 controls). Demographic details are in Table 1. The study protocol was approved by the KU Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Participants, and/or their legally acceptable representative, provided written, informed consent.

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics

| Mild AD (N=39) |

Controls (N=53) |

Total Sample (N=92) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 73.5 (7.9) | 73.2 (6.5) | 73.4 (7.1) |

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 21.6 (5.2) | 22.2 (5.4) | 22.1 (5.3) |

| Body Mass Index | 27.3 (5.0) | 26.4 (4.1) | 26.8 (4.5) |

| Total physical activity (vm)* | 378119.0 (32004.3) |

514326.3 (25877.24) |

456586.2 (203818.1) |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Mobility impairment (% indicating any impairment) | 6 (10.5%) | 4 (11.3%) | 10 (11.0%) |

| Female* | 11 (28.2%) | 37 (69.8%) | 48 (52.2%) |

| Race (% white) | 34 (87.2%) | 51 (96.2%) | 85 (92.4%) |

Difference between Mild AD and Control:

p < 0.01

SD = standard deviation; V02max = maximal oxygen consumption; ml/kg/min = milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body mass per minute; vm = vector magnitude

Physical activity measure

Body-worn accelerometers are designed to measure total physical activity, incorporating a variety of activities including ADLs (e.g., housework), lifestyle activities (e.g., walking for pleasure), and exercise. These measures indicate the total amount of movement across the period of data collection within an individual’s natural daily environment. In this study, total physical activity was measured using a hip-worn accelerometer (Actigraph GT3X+, Pensacola FL; Actigraph, 2012). The GT3x+ is a compact, light-weight, and unobtrusive triaxial accelerometer that has been validated across a range of community dwelling older adult samples [24]. Hip placement was chosen because this placement has greater sensitivity and specificity for measuring sedentary and low-intensity activities [25].

Participants were instructed to wear the unit on their dominant hip, secured by an elastic waist belt, 24 hours a day for seven days. Participants kept a wear-time diary used to determine compliance (identifying periods of device removal) as well as wake and sleep time. For participants with mild AD, study partners were asked to assist with completing the wear-time diaries and compliance as needed. After the data collection period, participants attended a follow-up visit where they returned the monitors, reviewed activity logs and completed additional questionnaires and maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) testing (described below).

The data cleaning protocol followed a three-step process. First vector magnitude data across three axes (medio-lateral (front-to-back), antero-posterior (side-to-side), and vertical (rotational)) collected every second was aggregated into one minute data. A single, tri-axial composite metric, or average vector magnitude (VM) was calculated for every minute of aggregated data ( ;[26]). As opposed to any uni-axial metric, average, VM provides a proximal metric of total body movement over a minute. Second, we excluded any data collection days where participants reported removing the device, other than during sleep time and while bathing. Third, we utilized the wear and non-wear time classification algorithm developed by Choi et al (freely available as an R package; “Physical Activity” downloadable at http://www.r-project.org/) [27, 28]. Briefly, this algorithm identifies wear and non-wear time based on patterns of zero and non-zero counts within each 24-hour period. We excluded all days with < 10 hours of wear time [29]. Participants provided on average 5.9 valid days of accelerometer data (range: 5–11 days).

As we were primarily interested in waking activity, or the activity phase of the daily diurnal cycle, accelerometry derived measures of physical activity were calculated during waking hours. Waking hours were defined as the interval of time between participant self-reported wake and sleep times recorded in wear-time diaries. Daily waking activity measures included daily averaged intensity metrics, and diurnal pattern metrics. Intensity metrics included amount of low-intensity and moderate-intensity activity per day, and number of minutes of sedentary activity per day. Intensity thresholds were based on previously published cut points for vector magnitude data derived from the Actigraph GT3X+ [30, 31], and included 0–149 counts/min for sedentary; 150–2689 counts/min for light-intensity; and 2690+ counts/min for moderate- to vigorous-intensity.

Diurnal pattern metrics were developed to describe how activity changed over the day. Rather than fitting a traditional cosine model (which may not approximate diurnal activity rhythms, particularly among diseased groups [32]) and estimating standard parameters, we directly calculated the following metrics: peak activity, or the maximum activity/minute during waking hours, and time of peak activity, or the time at which the peak activity minute occurred. To explore fluctuations in physical activity over the day relative to average activity, we calculated the root mean square deviation (RMSD), or standard deviation of all minute-to-minute physical activity intervals during waking hours. Prior evidence indicates that time dependent measures of variability, including RMSD, may provide an indication of an individual’s ongoing physical interaction with the environment including response to external demands [33]. This measure has also been previously used to measure the complexity of physiologic systems [33, 34], and indicates the extent to which an individual’s activity over a time period deviates from a flat, non-varying rhythm.

Covariates

Cardiorespiratory capacity, declines with age [35, 36], and is associated with the ability to complete ADLs and function independently [37]. Furthermore, the association between physical activity and cognition may be mediated by cardiovascular fitness [38]. We explored group differences in physical activity independent of cardiorespiratory capacity to better understand how AD may affect daily physical activity independent of the capacity to complete those activities. We measured maximal oxygen consumption, or VO2 max, by a graded treadmill exercise test using the modified Bruce protocol [39] designed for older adults. Briefly, participants began walking at a pace of 1.7 miles per hour at 0% incline; the grade and/or speed was increased at each subsequent two minute interval. Expired gases were collected continuously and oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide production were averaged at 15-second intervals (TrueOne 2400. Parvomedics, Sandy UT). VO2 max was calculated as the maximum milliliters of oxygen consumed in 1 minute per body weight in kilograms.

Variables that have also been shown previously to be associated with physical activity include body mass index (BMI), mobility impairment, age, sex, and race. We measured whole body mass using a digital scale accurate to ±0.1kg (Seca Platform Scale, Seca Corp., Columbia, MD), and height (in cm) was measured by stadiometer with shoes off—body mass index (BMI; weight (kg)/height (m2)) was then calculated from these measures. Self-report measures, including physical function and mobility, age, sex, and race, were reported by either the participant or study partner. Physical function and mobility measures (Yes/No) included 1) Difficulty using stairs; 2) Physical difficulty getting around the house independently; and 3) Use of a walking aid (cane or walker). We generated a summary score for mobility impairment defined as “yes” to any of the three mobility impairment measures or “no” to all three measures. Mobility impairment was included as a binary variable (Yes/No).

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline physical function, mobility, and socio-demographic differences between the mild AD and normal control groups, with a particular emphasis on factors that have been previously shown to be related to physical activity, as detailed above. We included total physical activity at baseline for descriptive purposes. We used t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables. We confirmed associations between VO2 max and daily low-intensity, moderate-intensity, and sedentary activities (vm) using Pearson correlations. For descriptive purposes, we explored percentage of waking minutes spent in sedentary, light-, and moderate-intensity physical activity across the two groups. We log-transformed moderate-intensity physical activity (log vm) due to its skewed distribution. This transformed variable was used in subsequent analyses.

Our main objective was to explore differences in physical activity between participants with mild AD and controls, independent of non-cognitive factors that may drive differences in physical activity, including VO2 max. We used multiple linear regression to model the relationship between physical activity intensity and diurnal patterns (dependent variables) and the main predictor of interest, group status (mild AD vs control). We first modeled the associations (Model 1) including covariates described above. Next, we explored the times of day when activity patterns between mild AD participants and controls diverged. We tested differences in physical activity metrics (Model 2) that were significant in Model 1 across the day, including the following time periods: morning (7:00am – 12:00pm), afternoon (12:00pm – 5:00pm), and evening (5:00pm – 10:00pm). Averaged participant self-reported wake (7:00 am) and sleep (10:00 pm) times were used to determine intervals for wake hours. These diurnal multivariate analyses included the same covariates used in Model 1. We plotted differences in physical activity over the day by group status to visualize results from Model 2. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp. 2013 Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Regression diagnostics for outliers and normality of distributions were performed by visual inspection.

Results

Table 1 presents characteristics of the study sample, comparing Mild AD and control groups. Groups did not vary on the majority of covariates potentially related to physical activity including age, VO2 max, body mass index, and race. Groups did vary significantly by sex. Mild AD participants were majority male while control participants were majority female. Mild AD participants had lower total physical activity compared to control participants. This study sample was very well suited to exploring physical activity differences independent of V02 max and other covariates considering the lack of significant differences across the majority of relevant covariates.

Supplementary figure 1 indicates correlations between physical activity intensity metrics and VO2 max. As expected, all metrics were significantly associated with VO2 max (ps < 0.01), with the strongest correlation for moderate-intensity physical activity (r = 0.605; p < 0.001). Supplementary figure 2 describes percentage of waking minutes spent within each intensity. Both the mild AD and control groups spent less than 3.2% of waking physical activity in the moderate-intensity range; the majority of physical activity was in the sedentary and low-intensity ranges.

Table 2 presents Model 1 results exploring differences in physical activity intensity and diurnal patterns by group (Mild AD vs control), controlling for covariates. Among intensity metrics, only moderate-intensity physical activity was significantly different between groups. Mild AD participants had less log vm daily moderate-intensity physical activity compared to controls. Among diurnal pattern metrics, peak activity and RMSD were both significantly different between groups. Mild AD participants had a lower peak activity. They also had a lower RMSD, a measure of physical activity complexity, compared to control participants suggesting that mild AD participants have less deviation from a flat, non-varying rhythm.

Table 2.

Model 1 results

| Metrics | Difference (Mild AD - Control) |

SE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | |||

| Low-intensity PA (vm) | −39,538.380 | 28,931.13 | 0.176 |

| Moderate-intensity PA (log vm) | −0.679* | 0.299 | 0.026 |

| Sedentary minutes | −5.738 | 26.691 | 0.830 |

| Diurnal pattern | |||

| Peak activity (vm) | −753.129** | 264.279 | 0.006 |

| Time of peak activity (min) | 59.877 | 36.284 | 0.103 |

| RMSD | −119.873* | 50.413 | 0.020 |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01; all models included the following covariates (in addition to group status): body mass index (BMI), age, race, V02 max, and mobility impairment.

PA = physical activity; vm = vector magnitude; β = beta coefficient from multiple regression model; SE = standard error; min = minutes; RMSD = root mean squared deviation

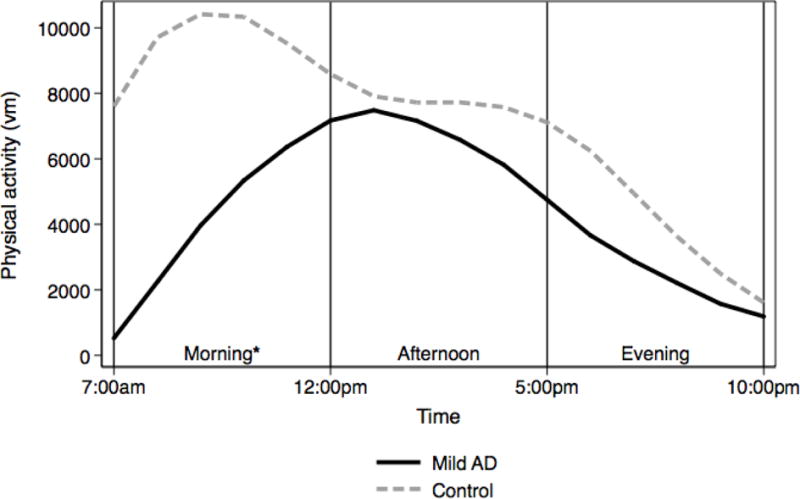

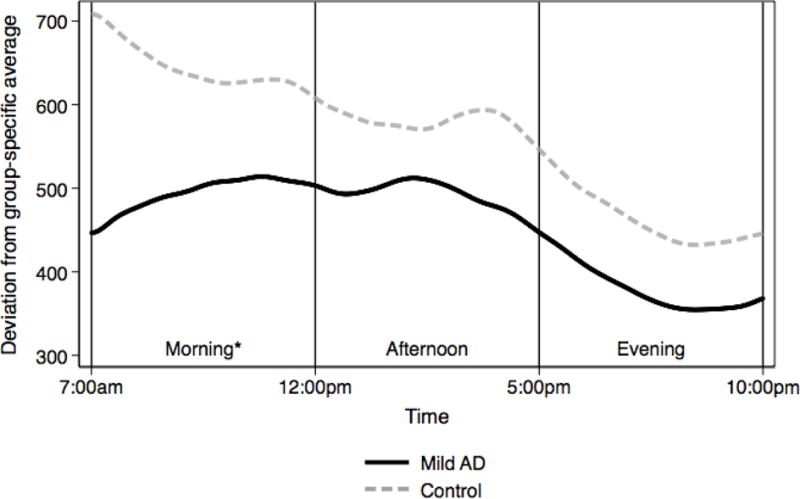

Table 3 presents Model 2 results exploring differences in metrics significant in Model 1 by time of day. We found that for all physical activity metrics, differences were greatest during the morning period (7am – 12pm). During this period, Mild AD participants had lower log vm moderate-intensity physical activity, lower vm peak activity and lower RMSD. Mild AD participants had lower vm peak activity in the afternoon but did not significantly differ from control participant on any metrics during the evening time period. We present plots of differences in moderate-intensity PA and peak activity by time period in Figures 1 and 2, which reflect results from Model 2. Figure 1 indicates that for moderate-intensity PA, individuals with mild AD have a unimodal diurnal shape, compared to a bimodal shape for controls, and show the greatest difference from controls in the morning. Figure 2 indicates that for RMSD, individuals with mild AD show the greatest difference during the morning, and have a generally flat pattern throughout the morning and afternoon followed by a decline in the evening. Controls show a gradually declining RMSD over the entire day with a peak at wake time.

Table 3.

Model 2 results

| Morning (7am – 12pm) | Afternoon (12pm – 5pm) | Evening (5pm – 10pm) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Difference (Mild AD - Control) | SE | p-value | Difference (Mild AD - Control) | SE | p-value | Difference (Mild AD - Control) | SE | p-value | |

| Moderate-intensity PA (log vm) | −0.566* | 0.253 | 0.028 | −0.43 | 0.254 | 0.094 | −0.329 | 0.212 | 0.124 |

| Peak activity | −625.736* | 270.305 | 0.023 | −389.725* | 192.751 | 0.047 | −104.200 | 181.184 | 0.567 |

| RMSD | −152.215* | 71.771 | 0.037 | −76.556 | 55.76 | 0.174 | −63.63 | 40.348 | 0.119 |

Note:

p < 0.05; all models included the following covariates (in addition to group status): body mass index (BMI), age, race, V02 max, and mobility impairment.

AD = Alzheimer’s disease; SE = standard error; PA = physical activity; vm = vector magnitude; RMSD = root mean squared deviation

Figure 1.

* difference significant at p < 0.05

Figure 2.

* difference significant at p < 0.05

Discussion

Our study compared daily patterns of physical activity in mild AD and a sample of cognitively normal older adults well-matched on non-cognitive factors that are strongly associated with physical activity including VO2 max. Independent of those factors, individuals with mild AD had significantly lower moderate-intensity physical activity, lower physical activity complexity (RMSD), and lower peak activity, particularly during the morning compared to cognitively normal controls. We did not find differences in low-intensity physical activity or sedentary activity across the entire day. These findings suggest that despite having similar physical function and capacity, individuals within the early stage of AD, compared to controls, show declines in moderate-intensity physical activity. This emphasizes the importance of a better mechanistic understanding of how cognitive decline and AD pathology impact components of physical activity including intensity and diurnal patterns across the day. It also highlights the potential value of designing and testing physical activity interventions targeting individuals in the early stages of AD, prior to significant declines in mobility and physical function.

Significant differences in moderate-intensity physical activity, physical activity complexity, and peak activity suggest that individuals with mild AD participate in less physically demanding and less physically complex activities particularly in the morning. Prior evidence indicates that cognitive decline and AD are associated with constricted life space and greater time spent at home [40]; Individuals with mild AD may spend less time in complex environments outside the home that may be more conducive to higher intensity physical activities [41, 42]. Our findings indicate that differences in moderate-intensity physical activity levels are not driven by differences in aerobic capacity (VO2 max), BMI, or other physical factors that may limit activity. This suggests that cognitive decline in the early stage of AD may limit physical activities particularly within the moderate-intensity range. Many moderate physical activities (e.g., dancing, mowing the lawn, sports, heavy cleaning) may be both more physically demanding and more cognitively complex than lower-intensity physical activities (e.g., sweeping, watering plants) and therefore may be more challenging for individuals with mild AD. These individuals may also be more cognitively dependent on a caregiver or other adult to facilitate or plan morning activities such as self-care or travel outside the home. However, the morning period may be the time of day when individuals with AD are the most alert [9, 43]. Therefore, the declines we observed in physical activity during this time period may be successfully buffered by well-designed interventions.

While moderate-intensity physical activity differed significantly between groups, low-intensity and sedentary activity, which comprised greater than 95% of daily waking activity, were not significantly different between the mild AD and control groups. This is consistent with evidence indicating that many daily activities may be preserved during the earliest stage of AD [7], and suggests that cognitive decline early in the disease course may not affect the majority of daily physical activities. Prior evidence indicates that sedentary behavior is associated with cognitive and physical function decline [44], and achievable and modest increases in physical activity within the low-intensity range may have health benefits [45–47]. Results of this study suggest that individuals with mild AD are an important target group for low-intensity physical activity interventions that modestly increase daily physical activity and reduce sedentary time. Future research should consider implementing multimodal low-intensity physical activity interventions (e.g., [17, 18]) that include both social and cognitive components and have been appropriately modified for individuals with cognitive decline.

While evidence suggests that fragmented sleep, daytime napping and other circadian disruptions are common in AD [9], less is known about how those disruptions may affect daily physical activity patterns, intensity, and peak activity times. This is one of the first studies to our knowledge to explore how physical activity during waking hours may be affected by mild AD. Future studies should bridge disciplines focused on circadian rhythms with physical activity to better understand how changes to the sleep-wake cycle may be associated with physical activity decline and how AD pathology may influence both.

This study has several limitations. First, the use of a hip worn accelerometer excludes certain physical activities, including swimming, cycling, and upper body activities, and may therefore underestimate total physical activity. Second, because the study is cross sectional, we cannot draw causal conclusions about the effect of mild AD on physical activity. While our study suggests that physical activity differences are not driven mainly by physical factors associated with mild AD, we did not directly test the hypothesis that cognitive or brain changes may be responsible. It is also possible that group differences in structural factors (i.e., neighborhood characteristics, presence of a caregiver) and psychological characteristics (i.e., self-efficacy, depressive symptoms) may contribute to results. Future longitudinal and mechanistic studies building on this work will help us better understand how cognitive decline and brain pathology associated with AD may directly impact patterns of physical activity. This study has a number of strengths including a study design that allowed us to specifically explore physical activity differences associated with mild AD in two groups approximately matched on VO2 max, age, and other non-cognitive factors associated with physical activity. We compared both intensity and diurnal pattern metrics derived from objective measures of physical activity that went beyond total average activity to more specifically characterize daily physical activity differences between groups. These analytic methods provide a more detailed profile of how physical activity may decline during early stages of the disease. Future studies exploring physical activity declines and physical activity interventions among individuals with AD should consider measuring diurnal variations in physical activity.

This study is among the first to use objective measures of physical activity and physical function to explore physical activity in the early stages of AD. Results provide support for exploring the effects of specifically timed physical activity interventions across intensities that may help slow the disease course and preserve independent function among AD patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (NIA 5P30AG035982-3) and a Clinical Translational Science Award grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences awarded to the University of Kansas Medical Center for Frontiers: The Heartland Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (#UL1TR000001; formerly #UL1RR033179). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NCATS.

References

- 1.Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Motor dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(12):1763–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.12.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Loss of motor function in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(5):665–76. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosso AL, Studenski SA, Chen WG, Aizenstein HJ, Alexander NB, Bennett DA, Black SE, Camicioli R, Carlson MC, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Hausdorff JM, Kaye J, Launer LJ, Lipsitz LA, Verghese J, Rosano C. Aging, the central nervous system, and mobility. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(11):1379–86. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olazaran J, Hernandez-Tamames JA, Molina E, Garcia-Polo P, Dobato JL, Alvarez-Linera J, Martinez-Martin P, A.D.R.U. Investigators Clinical and anatomical correlates of gait dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(2):495–505. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Campo N, Payoux P, Djilali A, Delrieu J, Hoogendijk EO, Rolland Y, Cesari M, Weiner MW, Andrieu S, Vellas B, M.D.S. Group Relationship of regional brain beta-amyloid to gait speed. Neurology. 2016;86(1):36–43. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baudic S, Barba GD, Thibaudet MC, Smagghe A, Remy P, Traykov L. Executive function deficits in early Alzheimer’s disease and their relations with episodic memory. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;21(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stages of Alzheimer’s. 2016 [cited 2016 April 28]; Available from: http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_stages_of_alzheimers.asp.

- 8.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1173–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musiek ES, Xiong DD, Holtzman DM. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e148. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran M, Lynch CA, Walsh C, Coen R, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Sleep disturbance in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med. 2005;6(4):347–52. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonanni E, Maestri M, Tognoni G, Fabbrini M, Nucciarone B, Manca ML, Gori S, Iudice A, Murri L. Daytime sleepiness in mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease and its relationship with cognitive impairment. J Sleep Res. 2005;14(3):311–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehrman P, Marler M, Martin JL, Shochat T, Corey-Bloom J, Ancoli-Israel S. The relationship between dementia severity and rest/activity circadian rhythms. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(2):155–63. doi: 10.2147/nedt.1.2.155.61043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolland Y, Abellan van Kan G, Vellas B. Physical activity and Alzheimer’s disease: from prevention to therapeutic perspectives. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(6):390–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, Kukull WA, LaCroix AZ, McCormick W, Larson EB. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2015–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santana-Sosa E, Barriopedro MI, Lopez-Mojares LM, Perez M, Lucia A. Exercise training is beneficial for Alzheimer’s patients. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29(10):845–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Heo S, Alves H, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Mailey E, Vieira VJ, Martin SA, Pence BD, Woods JA, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried LP, Carlson MC, Freedman M, Frick KD, Glass TA, Hill J, McGill S, Rebok GW, Seeman T, Tielsch J, Wasik BA, Zeger S. A social model for health promotion for an aging population: initial evidence on the Experience Corps model. J Urban Health. 2004;81(1):64–78. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park DC, Lodi-Smith J, Drew L, Haber S, Hebrank A, Bischof GN, Aamodt W. The impact of sustained engagement on cognitive function in older adults: the Synapse Project. Psychol Sci. 2013;25(1):103–12. doi: 10.1177/0956797613499592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettersson AF, Olsson E, Wahlund LO. Motor function in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19(5–6):299–304. doi: 10.1159/000084555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobol NA, Hoffmann K, Vogel A, Lolk A, Gottrup H, Hogh P, Hasselbalch SG, Beyer N. Associations between physical function, dual-task performance and cognition in patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1063108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graves RS, Mahnken JD, Swerdlow RH, Burns JM, Price C, Amstein B, Hunt SL, Brown L, Adagarla B, Vidoni ED. Open-source, Rapid Reporting of Dementia Evaluations. J Registry Manag. 2015;42(3):111–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguilar-Farias N, Brown WJ, Peeters GM. ActiGraph GT3X+ cut-points for identifying sedentary behaviour in older adults in free-living environments. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(3):293–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleland I, Kikhia B, Nugent C, Boytsov A, Hallberg J, Synnes K, McClean S, Finlay D. Optimal placement of accelerometers for the detection of everyday activities. Sensors (Basel) 2013;13(7):9183–200. doi: 10.3390/s130709183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ActiLife 6 User’s Manual. Pensacola, FL: ActiGraph Software Department; 2012. Actigraph. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi L, Liu Z, Matthews CE, Buchowski MS. Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(2):357–64. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ed61a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi L, Ward SC, Schnelle JF, Buchowski MS. Assessment of wear/nonwear time classification algorithms for triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(10):2009–16. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318258cb36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masse LC, Fuemmeler BF, Anderson CB, Matthews CE, Trost SG, Catellier DJ, Treuth M. Accelerometer data reduction: a comparison of four reduction algorithms on select outcome variables. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S544–54. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185674.09066.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr LJ, Mahar MT. Accuracy of intensity and inclinometer output of three activity monitors for identification of sedentary behavior and light-intensity activity. J Obes. 2012;2012:460271. doi: 10.1155/2012/460271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kozey-Keadle S, Libertine A, Lyden K, Staudenmayer J, Freedson PS. Validation of wearable monitors for assessing sedentary behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1561–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31820ce174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Refinetti R. Non-parametric procedures for the determination of phase markers of circadian rhythms. Int J Biomed Comput. 1992;30(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/0020-7101(92)90061-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavanaugh JT, Kochi N, Stergiou N. Nonlinear analysis of ambulatory activity patterns in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(2):197–203. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein PK, Bosner MS, Kleiger RE, Conger BM. Heart rate variability: a measure of cardiac autonomic tone. Am Heart J. 1994;127(5):1376–81. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawkins S, Wiswell R. Rate and mechanism of maximal oxygen consumption decline with aging: implications for exercise training. Sports Med. 2003;33(12):877–88. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Betik AC, Hepple RT. Determinants of VO2 max decline with aging: an integrated perspective. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33(1):130–40. doi: 10.1139/H07-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shephard RJ. Maximal oxygen intake and independence in old age. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(5):342–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kramer AF, Erickson KI, Prakash R. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference: Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline. NIH Consensus Development Program; Bethesda, MD: 2010. Risk reduction factors for Alzheimer’s Disease and cognitive decline in older adults: physical activity. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hollenberg M, Ngo LH, Turner D, Tager IB. Treadmill exercise testing in an epidemiologic study of elderly subjects. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(4):B259–67. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.4.b259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.James BD, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Life space and risk of Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(11):961–9. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318211c219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Troped PJ, Wilson JS, Matthews CE, Cromley EK, Melly SJ. The built environment and location-based physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):429–38. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis MG, Fox KR, Hillsdon M, Sharp DJ, Coulson JC, Thompson JL. Objectively measured physical activity in a diverse sample of older urban UK adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(4):647–54. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181f36196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A. Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):704–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thyfault JP, Du M, Kraus WE, Levine JA, Booth FW. Physiology of sedentary behavior and its relationship to health outcomes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(6):1301–5. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watts AS, Vidoni ED, Loskutova N, Johnson DK, Burns JM. Measuring Physical Activity in Older Adults with and without Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin Gerontol. 2013;36(4):356–374. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2013.788116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Varma VR, Chuang Y, Harris GC, Tan EJ, Carlson MC. Low-intensity daily walking activity is associated with hippocampal volume in older adults. Hippocampus. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hipo.22397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varma VR, Tan EJ, Wang T, Xue QL, Fried LP, Seplaki CL, King AC, Seeman TE, Rebok GW, Carlson MC. Low-Intensity Walking Activity is Associated with Better Health. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33(7):870–887. doi: 10.1177/0733464813512896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.