Abstract

Introduction

Heart rate (HR) reduction is an integral part of antianginal therapy, but many patients do not reach the guideline-recommended target of less than 60 bpm despite high use of beta-blockers (BB). Failure to uptitrate BB doses may be partly to blame. To explore other options for lowering HR and improving angina control, CONTROL-2 was initiated to compare the efficacy and tolerability of the combination of BBs with ivabradine versus uptitration of BBs to maximal tolerated dose, in patients with stable angina.

Methods

This multicenter, open, randomized study included 1104 patients with Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class II or III stable angina, in sinus rhythm, and on background stable treatment with non-maximal recommended doses of BBs. Consecutive patients were allocated to ivabradine + BB or BB uptitration in a 4:1 ratio.

Results

At the end of the study (week 16), addition of ivabradine to BB treatment and BB uptitration resulted in reduction in HR (61 ± 6 vs. 63 ± 8 bpm; p = 0.001). At week 16, significantly more patients on ivabradine + BB were in CCS class I than with BB uptitration (37.1% vs. 28%; p = 0.017) and significantly more patients were angina-free (50.6% vs. 34.2%; p < 0.001). Patient health status based on the visual analogue scale (VAS) was also better in the ivabradine + BB group. Adverse events (AEs) were significantly more common with BB uptitration than with the ivabradine + BB combination (18.4% vs. 9.4%, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In patients with stable angina, combination therapy with ivabradine + BB demonstrated good tolerability, safety, and more pronounced clinical improvement, compared to BB uptitration.

Trial Registration

ISRCTN30654443.

Funding

Servier.

Keywords: Beta-blockers, Cardiology, Ivabradine, Patient health status, Stable angina, Treatment

Introduction

In 2015, coronary artery disease (CAD) was the leading cause of death worldwide [1] and, although many patients now survive acute myocardial infarction (AMI), a significant proportion are left with angina pectoris [2]. Indeed, angina due to CAD affects around 112 million people worldwide [3]. Although annual mortality from angina is relatively low [4, 5], symptoms are often disabling and adversely affect patient quality of life. In a global study, the highest rates of CAD disability were found in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, and stable angina made the largest contribution to CAD disability, with smaller contributions from ischemic heart failure and nonfatal AMI [6]. Angina also has a significant impact on healthcare costs, and it has been demonstrated that, following acute coronary syndrome, healthcare resource utilization in patients with angina is double that of patients without symptoms [7].

The treatment of patients with stable angina is focused primarily on relief of symptoms, improvement of quality of life, and prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events [8]. HR reduction is an integral part of antianginal therapy; the target rate is below 60 bpm [8, 9] and BB, calcium channel blockers, and ivabradine are recommended to reduce HR and symptoms [8]. Data from the large international CLARIFY registry demonstrated that despite high BB usage, patients with stable angina often had a resting HR greater than 70 bpm, and this was associated with more frequent angina and ischemia [10]. This may be related, in part, to failure to increase doses of BBs and discontinuation of therapy [11], and there is a clear need for further lowering of HR in many patients with stable angina.

Ivabradine is the first selective inhibitor of the cardiac pacemaker If current that controls spontaneous diastolic depolarization in the sinus node and reduces HR [12]. It is indicated for the symptomatic treatment of chronic stable angina in adults with CAD with normal sinus rhythm and HR of at least 70 bpm as well as for management of chronic heart failure patients.

Ivabradine improves coronary blood flow through different mechanisms compared with BBs and this raises the opportunity for combination treatment in patients who remain symptomatic with BB therapy alone. In a small study of patients with stable angina, combination treatment with ivabradine and bisoprolol reduced angina symptoms and improved exercise capacity compared with an increased dose of bisoprolol [13]. In the larger placebo controlled ASSOCIATE study, addition of ivabradine to atenolol treatment resulted in significant improvements in exercise capacity in patients with stable angina [14].

To improve our understanding about the broader potential for combination treatment with ivabradine and BBs, we initiated the CONTROL-2 study in a large population of patients in Russia with stable angina on submaximal doses of BBs. The study compared the effects of adding ivabradine to BBs versus uptitration of BBs on HR, angina attacks, nitroglycerin use, and patient health status. The research has been previously published in Russian [15].

Methods

The CONTROL-2 study was a multicenter, open, randomized, prospective study with the inclusion of consecutive patients. A total of 389 doctors from 72 cities of the Russian Federation (RF) participated in the study, including cardiologists (232; 60.6%), general practitioners (GPs) (121; 31.6%), and internal medicine physicians (30; 7.8%).

Study participants were adult patients (≥ 18 years) with documented angina of effort, CCS class II–III, which had been stable for at least 3 months, with at least three attacks per week. Patients were in sinus rhythm with HR of at least 60 bpm and were undergoing regular treatment of stable angina with a BB in a dose which was below the maximum for angina treatment. Exclusion criteria included chronic heart failure of NYHA class III–IV, non-sinus rhythm, blood pressure greater than 180/100 mmHg at rest, and treatment with verapamil or diltiazem.

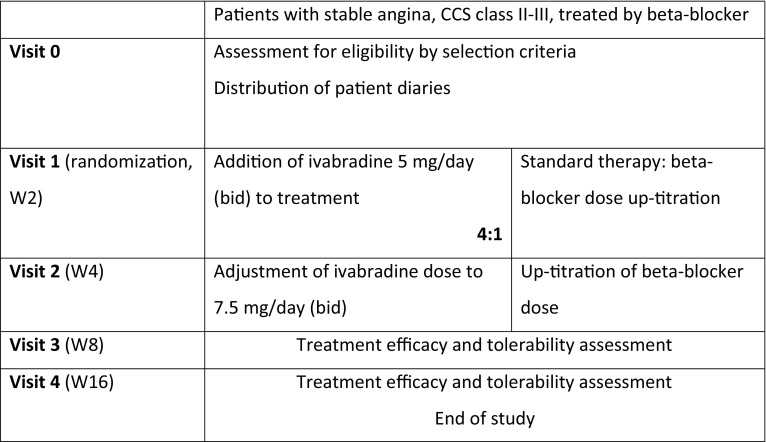

The study design is outlined in Fig. 1. Consecutive patients were allocated to standard therapy with BB uptitration to the maximal tolerated dose or ivabradine was added to their current BB dose, in a 1:4 ratio of patients. This treatment allocation ratio was used to increase the chance of detecting any tolerability problems related to combination of ivabradine with BB. Uptitration of BB was carried out according to achieved resting HR and tolerability as, in contrast to heart failure, there is no recommended target dose or recommended BB molecule in treating stable angina, and thus a wide variety of agents and doses are commonly used: atenolol 25–100 mg/day [16], bisoprolol 2.5–10 mg/day [16, 17], betaxolol 5–20 mg/day [16], carvedilol 6.25–100 mg/day [16], nebivolol 2.5–5 mg/day [16, 17], metoprolol 50–200 mg/day [16, 17], and propranolol 40–320 mg/day [16].

Fig. 1.

Design of the CONTROL-2 study

Five clinic visits were performed: at baseline (visit 0), at 2 weeks (visit 1), at 4 weeks (visit 2), at 8 weeks (visit 3), and finally at 16 weeks (visit 4).

Clinical outcomes were change in HR during the 16-week treatment period, change in CCS class of angina, number of angina attacks with standard therapy vs. ivabradine, proportion of patients who were angina-free between study visits, and patient self-reported health status (visual analog scale, VAS). The quantitative parameters are presented as the mean arithmetic value and standard deviation, if values were normally distributed, or as the median with 25th and 75th percentiles, if values were not normally distributed. Differences in the quantitative variables between groups were analyzed using a Student’s t test for independent samples with parametric distribution of values, or the Mann–Whitney test when samples demonstrated non-parametric distribution. Changes in the quantitative variables during the treatment were analyzed using a Student’s t test for paired samples or a Wilcoxon test for nonparametric parameters. Differences in the categorical variables between the groups were analyzed using a Pearson’s Chi squared test with Yates’ correction. Changes in the categorical variables during treatment were analyzed using a McNemar’s test. Differences were considered as statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national), the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013, and the European Independent Ethics Committee. The CONTROL-2 protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry (no. 18/2 dd. 22/09/2009; Moscow). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The study has been registered at ISRCTN registry with study ID ISRCTN30654443.

Results

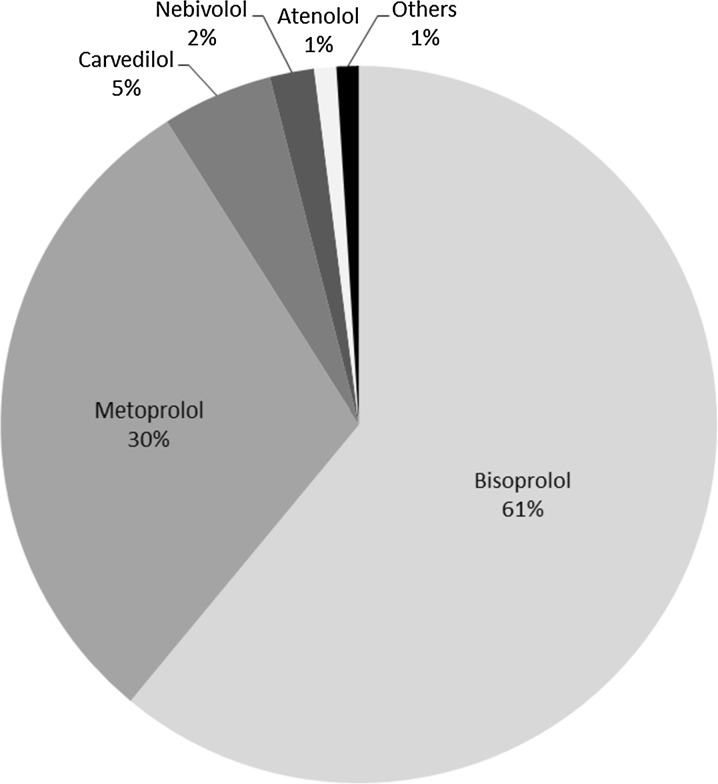

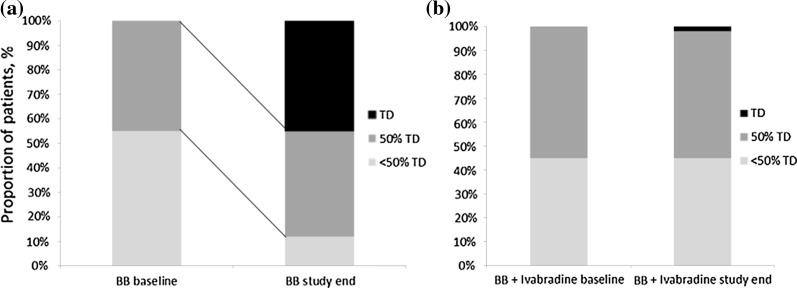

During the period from November 2009 to April 2010, 1104 patients were enrolled into the study (BB uptitration: 228 patients, 20.7%; ivabradine + BB: 876 patients, 79.3%). Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups, except for HR which was significantly higher in the ivabradine + BB group (Table 1). The most frequently used BBs were bisoprolol and metoprolol (Fig. 2). Both groups, received adequate doses of standard therapy with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) (> 80%), statins (75%), and antiplatelet therapy (> 90%) (Table 2). At baseline, no patients had achieved maximal doses of BB, though a higher proportion of patients in the ivabradine + BB group were prescribed BBs at 50% or more of the recommended maximal dose than those in the BB uptitration group (55% vs. 45%) (Fig. 3 and Table 3). At the end of the study (week 16), treatment with BB was reported in 227 (99.6%) of patients in the BB uptitration group and 863 (98.5%) of patients in the ivabradine + BB group (p = 0.323). Forty-five percent of patients had achieved the maximal therapeutic BB dosage in the BB uptitration group but, as might be expected, there was little change in BB dose in patients taking ivabradine + BB (Fig. 3). The rates of administration of individual BBs by the end of the study were similar in both groups, but the doses were significantly different. By the end of the study, the daily dose of ivabradine was 5 mg (bid) in 220 (25.2%) patients and 7.5 mg (bid) in 654 (74.8%) patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the CONTROL-2 study (n = 1075)

| Parameter | Standard therapy group, n = 228 | Ivabradine group, n = 876 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | |||

| Age, years | 61.2 ± 9.3 | 60.0 ± 9.6 | 0.097 |

| ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 70 (31.5) | 248 (29.6) | 0.633 |

| Female, n (%) | 105 (46.1) | 437 (49.9) | 0.339 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.9 ± 4.4 | 28.7 ± 5.1 | 0.603 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, n (%) | 76 (33.3) | 275 (31.4) | 0.638 |

| Medical history | |||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 202 (88.6) | 745 (85.0) | 0.207 |

| Previous MI, n (%) | 91 (39.9) | 320 (36.5) | 0.387 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 18 (7.9) | 41 (4.7) | 0.079 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 15 (6.6) | 38 (4.3) | 0.216 |

| CHF, class I/II NYHA, n (%) | 56 (24.6)/107 (46.9) | 163 (18.6)/412 (47.0) | 0.078 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (14.9) | 130 (14.8) | 1.000 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 28 (12.3) | 107 (12.2) | 1.000 |

| Stroke or TIA, n (%) | 16 (7.0) | 37 (4.2) | 0.113 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 17 (1.9) | 0.394 |

| COPD, n (%) | 19 (8.3) | 89 (10.2) | 0.483 |

| Depression, n (%) | 17 (7.5) | 80 (9.1) | 0.506 |

| Erectile dysfunction, n (%) | 24 (19.5) | 87 (19.8) | 1.000 |

| Clinical findings | |||

| Number of angina attacks per week | 7 (4; 12) | 7 (4; 10) | 0.818 |

| Number of nitroglycerin tablets per week | 7 (4; 11) | 7 (4; 10) | 0.846 |

| Angina of class III, n (%) | 67 (29.5) | 279 (31.9) | 0.538 |

| SBP, mmHg | 144.9 ± 15.6 | 143.0 ± 17.5 | 0.115 |

| DBP, mmHg | 86.8 ± 8.6 | 86.5 ± 8.9 | 0.409 |

| HR, bmp | 83.2 ± 10.9 | 85.1 ± 10.4 | 0.015 |

| LVEF, % | 55.3 ± 7.7 | 56.0 ± 8.4 | 0.588 |

| Coronary angiography, n (%) | 48 (21.1) | 139 (15.9) | 0.078 |

| Positive stress echo test, n (%) | 10 (4.4) | 48 (5.5) | 0.622 |

| Positive exercise tolerance test, n (%) | 123 (53.9) | 480 (54.8) | 0.877 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation, or mean (25th; 75th percentiles)

BMI body mass index, bpm beats per minute, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CHF chronic heart failure, MI myocardial infarction, TIA transient ischemic attack, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Fig. 2.

Beta-blocker treatment at baseline

Table 2.

Treatment prior to study inclusion

| Treatments | Prescription rate, n (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard therapy group, n = 228 | Ivabradine group, n = 876 | ||

| Aspirin or other antiplatelet drugs | 210 (92.1) | 811 (92.6) | 0.919 |

| Long-acting nitrates | 110 (48.2) | 443 (50.6) | 0.582 |

| Lipid lowering drugs | 169 (74.1) | 655 (74.8) | 0.908 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 39 (17.1) | 149 (17.0) | 1.000 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 161 (70.6) | 639 (72.9) | 0.536 |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonists | 26 (11.4) | 84 (9.6) | 0.490 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 45 (19.7) | 130 (14.8) | 0.089 |

| Trimetazidine | 36 (15.8) | 123 (14.0) | 0.573 |

Fig. 3.

Change in beta-blocker dosages in the study in BB uptitration group (a) and in BB + ivabradine group (b)

Table 3.

Change in beta-blocker dosages in the study

| Range of dosages of BB | Baseline, N (%) | p value | Study end, N (%) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard therapy, n = 228 | Ivabradine, n = 876 | Standard therapy, n = 228 | Ivabradine, n = 876 | |||

| ≥ 50% of maximal dosage (but less than maximal dosage) | 102 (44.7) | 481 (54.9) | 0.008 | 95 (41.6) | 453 (52.6) | 0.001 |

| Maximal dosage | – | – | 103 (45.1) | 24 (2.8) | 0.005 | |

| < 50% of maximal dosage | 126 (55.3) | 395 (45.1) | 0.028 | 30 (13.1) | 385 (44.6) | 0.001 |

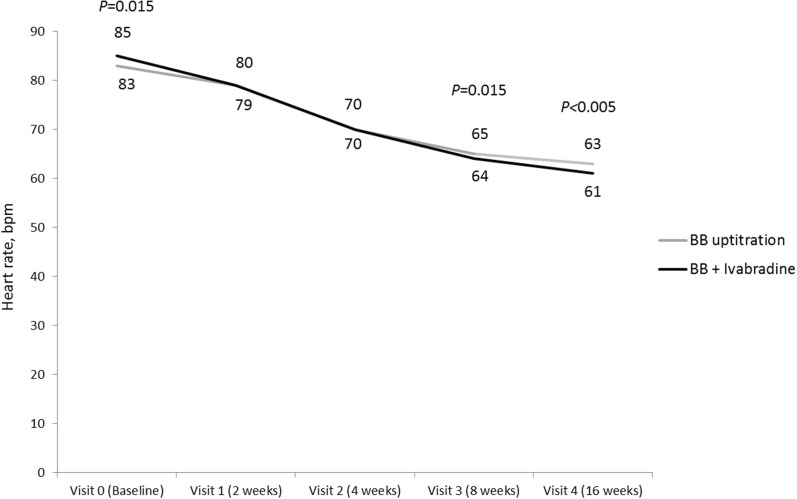

HR was reduced substantially in both groups from 83.2 ± 10.9 to 63 ± 8 bpm in the BB uptitration group and from 85.1 ± 10.4 to 61 ± 6 bmp in the ivabradine + BB group (Fig. 4). In both groups, the target HR (55–60 bpm) was achieved in approximately half of the patients with stable angina.

Fig. 4.

Change in HR during the 16-week treatment period

Comparable reductions in blood pressure were seen for the two groups, from 145/87 to 125/78 mmHg in the BB uptitration group and 143/87 to 126/78 mmHg in the ivabradine + BB group.

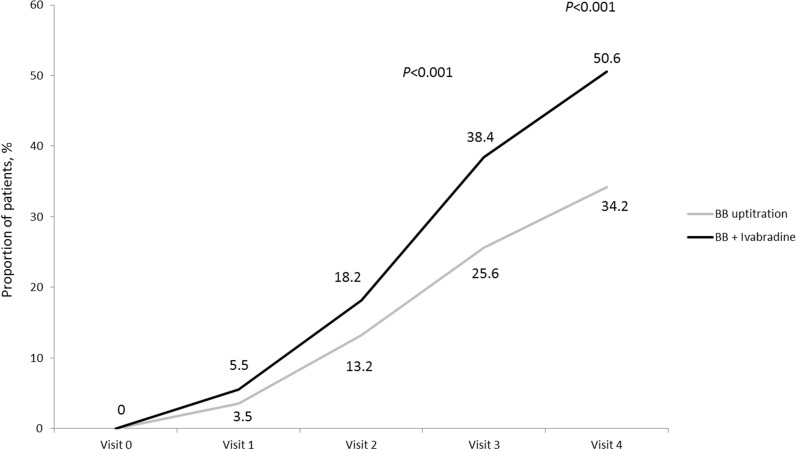

The optimization of treatment resulted in a substantial antianginal effect in both groups. However, by the end of 16-week treatment the proportion of patients with CCS class I angina was significantly higher in the ivabradine + BB group than with BB uptitration (37.1% vs. 28%, respectively; p = 0.017), while at the beginning of the study there were no patients with CCS class I angina in either group. The proportion of patients who were free of angina after week 8 and week 16 of the study was significantly greater with ivabradine + BB than with BB uptitration (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Proportion of patients free of angina in the period between visits

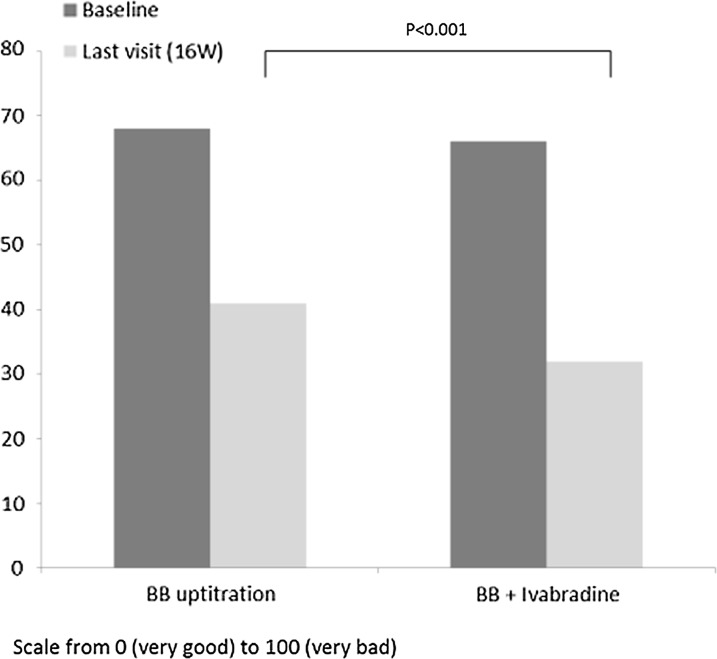

Analysis of patient diaries showed that there was a reduction in the rate of angina attacks and nitroglycerin consumption in both groups (Table 4). However, by the end of the study, the need for nitroglycerin in the BB + ivabradine group was significantly lower: 1 (0; 2) vs. 2 (1; 3), p = 0.015 s. Patient health status, based on the results of the VAS, improved in both groups, from 67 (51; 78) to 41 (29; 65) in the BB uptitration group and from 65 (48; 78) to 32 (18; 47) in the ivabradine + BB group. This improvement was higher in the ivabradine + BB group than in the uptitration group (p = 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Table 4.

Changes in angina attacks and SAN use (median (IQR))

| Number of angina attacks per week | SAN use per week | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (standard therapy) | Group 2 (addition of ivabradine) | p | Group 1 (standard therapy) | Group 2 (addition of ivabradine) | p | |

| Baseline | 5 (3; 7) | 4 (2; 8) | 0.31 | 4 (2; 8) | 4 (2; 8) | 0.71 |

| W2 | 3 (2; 6) | 3 (2; 5) | 0.83 | 3 (1; 5) | 2 (1; 5) | 0.67 |

| W4 | 2 (1; 5) | 2 (1; 5) | 0.75 | 2 (1; 5) | 2 (1; 4) | 0.05 |

| W8 | 2 (1; 4) | 2 (1; 3) | 0.87 | 2 (1; 3) | 1 (0; 3) | 0.06 |

| W16 | 2 (1; 4) | 2 (1; 3) | 0.33 | 2 (1; 3) | 1 (0; 2) | 0.01 |

Fig. 6.

Change in patient health status (VAS) with treatment

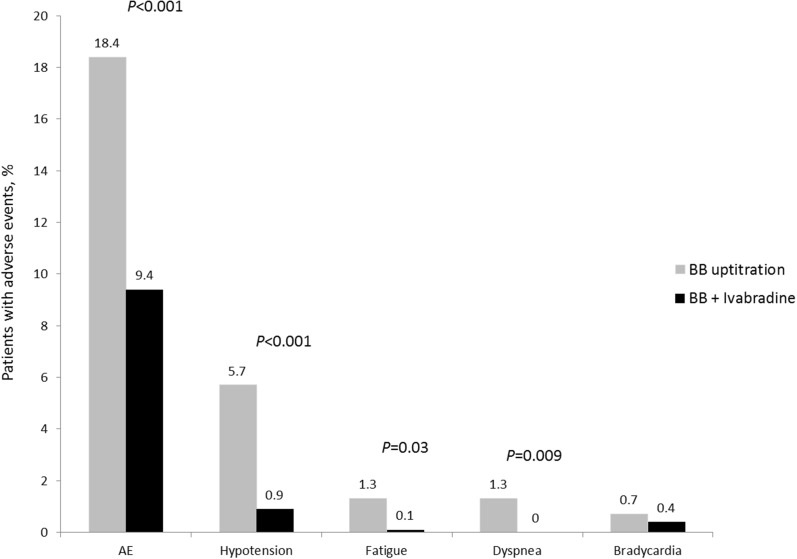

Adverse Events

AEs were significantly more common in the BB uptitration than the ivabradine + BB group (18.4% vs. 9.4%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 7). The rates of asthma, dyspnea, hypotension, and fatigue were all significantly higher in the BB uptitration group (Table 5). Hospital admissions (for any reason) were reported more often in the standard therapy group [6 cases (2.6%) vs. 8 cases (0.9%), p = 0.083]. Death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke were reported in 3 (1.3%) and 2 (0.2%) cases, respectively (p = 0.063). HR less than 50 bmp was registered on at least one visit (1–4) in 7 patients: 1 (0.4%) from the BB uptitration group and 6 (0.7%) from the ivabradine + BB group (p = 1.000).

Fig. 7.

Selected adverse events

Table 5.

Adverse events, n (%)

| Group 1 (standard therapy) | Group 2 (addition of ivabradine) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphenes | 0 (0) | 10 (1.1) | 0.230 |

| Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, constipation) | 1 (0.4) | 8 (0.9) | 0.695 |

| Cough | 0 (0) | 5 (0.6) | 0.590 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | 0.501 |

| Asthma, dyspnea | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0.009 |

| Bradycardia | 2 (0.9) | 11 (1.3) | 1.000 |

| Hypotension | 13 (5.7) | 8 (0.9) | 0.001 |

| Headache | 3 (1.3) | 7 (0.8) | 0.440 |

| Dizziness | 6 (2.6) | 10 (1.1) | 0.172 |

| Weakness | 8 (3.5) | 16 (1.8) | 0.195 |

| Fatigue | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0.030 |

| Seizures, pain in the muscles of the legs | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 1.000 |

| Sleep disorders | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0.371 |

Discussion

In the CONTROL-2 trial, we found that combination treatment with ivabradine and BBs resulted in significantly more pronounced antianginal efficacy for patients than uptitration of BBs, with a higher proportion of patients becoming angina-free: half of the patients receiving combination therapy with ivabradine and BBs became angina-free, compared with approximately one-third of the patients receiving standard uptitration with BBs.

The addition of ivabradine to BB therapy was also better tolerated than uptitration of BBs, and the enhanced efficacy and tolerability were reflected in a greater improvement in patient health status in the ivabradine + BB group.

Factors which may have contributed to the superiority of combination treatment with ivabradine + BB over uptitration of BBs include the failure of over half of the patients in the uptitration group to reach maximal therapeutic doses of BB, and complementary effects of ivabradine on coronary flow. BBs act directly on the heart to reduce HR, also affecting myocardial contractility and atrioventricular conduction [8]. They increase perfusion of ischemic areas by prolonging diastole and increasing vascular resistance in non-ischemic areas [8] but also impair isovolumic ventricular relaxation and thus offset part of the benefit in terms of the diastolic pressure–time integral [18]. Unlike BBs, ivabradine has no negative inotropic and lusitropic effects for a comparable reduction in HR, resulting in more prolonged diastolic duration than with BBs [19]. In addition, ivabradine does not unmask alpha-adrenergic vasoconstriction and, unlike BBs, therefore maintains coronary dilatation during exercise [19]. Compared to BBs, ivabradine also increases coronary flow reserve and collateral perfusion, promoting the development of coronary collaterals [19]. There is also evidence from experimental and clinical studies that ivabradine may reduce myocardial ischemia and its consequences not only through HR reduction but also through additional pleiotropic mechanisms which could include attenuated formation of reactive oxygen species in cardiomyocyte mitochondria [20–22]. Some data from clinical studies also support some heart rate-independent benefit from ivabradine. For example the improved coronary flow velocity reserve was reported with ivabradine in patients with stable CAD when HR reduction was abrogated by atrial pacing [23]. In another study in patients with stable CAD, ivabradine improved coronary flow velocity reserve to a significantly greater extent than bisoprolol despite the same HR reduction [24]. Together, these additional properties of ivabradine may help to explain the beneficial antianginal effects of combination therapy with BBs compared with BB uptitration.

The advantages of combination treatment with ivabradine + BBs for patients with stable angina that we have seen in CONTROL-2 are supported by data from previous randomized studies [13, 14]. In a study of 24 patients with stable angina, comparable reductions in mean resting HR were seen after 2 months with ivabradine in combination with bisoprolol 5 mg vs. bisoprolol uptitrated from 5 to 10 mg. There was a significantly greater reduction in weekly number of angina attacks requiring sublingual nitrate consumption with combination therapy (p = 0.041) [13]. In the ASSOCIATE study, addition of ivabradine (5–7.5 mg bid) to atenolol 50 mg od resulted in significant improvements in exercise capacity at 4 months, relative to placebo, in patients with stable angina pectoris receiving BB therapy [25].

In the REDUCTION study carried out in everyday clinical practice, significant reductions in HR (p < 0.0001) and angina episodes (p < 0.0001) were seen at 4-month follow-up in a cohort of 344 patients treated with both ivabradine and BBs [26]. Efficacy and tolerance were graded as “very good/good” for 96% and 99% of the patients treated [26]. Further support for the ivabradine + BB combination approach in stable angina comes from pooled data from three large observational studies with a total of 8555 patients in which ivabradine therapy for 4 months was associated with a significant reduction in the frequency of angina attacks (p < 0.0001) and consumption of short-acting nitrates (p < 0.0001), irrespective of age, comorbidities, and BB use [27]. HR was reduced by 16% during ivabradine treatment, and 85% of patients achieved an HR of less than 70 bpm or a reduction of at least 10 bpm. Improvements were also seen in clinical status and QoL [27].

Clinical Implications

Given the potential for synergistic effects between BBs and ivabradine, the results of CONTROL-2 suggest that, in patients who remain symptomatic while taking BBs, combining ivabradine and BBs provides better efficacy than uptitrating the BB dose.

The data on better efficacy of the combination of ivabradine and BB support the rationale for a fixed-dose combination of ivabradine and metoprolol which is now available for use in clinical practice and could be beneficial in terms of adherence to treatment, which could further improve the antianginal effects of this combination therapy.

Limitations

The HR threshold for entry into CONTROL-2 (≥ 60 bpm) was below the HR threshold of at least 70 bpm currently recommended for ivabradine treatment. However, as the population characteristics at baseline clearly show (Table 1), all of the patients in the study had an HR greater than 70 bpm. Indeed, patients in the ivabradine + BB group had a significantly higher baseline HR than those in the BB uptitration group, owing to the open design of the study. Although randomization of patients in CONTROL-2 was not computer generated, the use of consecutive patient randomization in a 4:1 ratio for ivabradine + BB versus BB uptitration should have eliminated the potential for investigator bias, resulting in patients being assigned to study treatments according to perceived disease severity.

The proportion of patients who had undergone surgery/procedures for stable angina (coronary artery bypass grafting and percutaneous coronary intervention) was lower than would be expected in many European and US populations. In CONTROL-2, less than 8% of patients in the BB uptitration group and less than 5% of those on ivabradine + BB had had CABG, and less than 7% and less than 5%, respectively, had had PCI. This compared with 22% and 59% in the REDUCTION study carried out in Germany [26]. However, the findings in CONTROL-2 are typical of practice in Russia, where access to such interventions is limited.

CONTROL-2 underlined the challenge of reducing HR and improving angina symptoms with BBs alone, and the difficulty of uptitration of BB owing to tolerability problems. Previous data from the CLARIFY registry in stable CAD showed that 41% of patients taking BB had a HR of at least 70 bpm, and only 22% of those with angina symptoms had an HR of 60 bpm or less [9]. In a UK study of 500 patients undergoing PCI for chronic stable angina, 78% were receiving BBs, at a mean equivalent dose of bisoprolol of 3.1 mg [28]—at the lower end of the recommended dose range [16, 17] In the CONTROL study in patients with stable angina, carried out previously, mean BB doses were also low (bisoprolol 5 mg, metoprolol 50 mg, nebivolol 5 mg) [29].

Conclusions

In patients with stable angina, combination therapy with ivabradine and BBs demonstrated more pronounced clinical improvement in patient health status compared to BB uptitration. Treatment was well tolerated and effectively addressed the current failure to optimize angina and HR control with BBs alone owing, at least in part, to inability to reach satisfactory doses.

Acknowledgements

The research was previously published in Russian and has been translated to English with permission from the original publisher.

Funding

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access fee for this study were provided by Servier, France. The study was supported by a research grant from Servier, Russia. The funding source had no role in the study design, in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication but did assist with the setup, data collection, and management of the study in each country. The sponsor funded editorial support for editing and revision of the manuscript and received the manuscript for review before submission.

Medical Writing and Assistance

Writing assistance was provided by Jenny Bryan and funded by Servier, France.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Thanking Investigators

The authors would like to thank all participating investigators for their contribution to the study.

Disclosures

Yuri Karpov received honoraria as scientific coordinator of this study and for lectures from “Servier”, Moscow, Russian Federation. Yuri Vasyuk received honoraria for lectures from “Servier”, Moscow, Russian Federation. Maria Glezer received honoraria for lectures from “Servier”, Moscow, Russian Federation.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national), the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013, and the European Independent Ethics Committee. The CONTROL-2 protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry (no. 18/2 dd. 22/09/2009; Moscow). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.5903644.

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maddox TM, Reid KJ, Spertus JA, et al. Angina at 1 year after myocardial infarction: prevalence and associated findings. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1310–1316. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dargie HJ, Ford I, Fox KM. Total Ischemic Burden European Trial (TIBET). Effects of ischaemia and treatment with atenolol, nifedipine SR and their combination on outcome in patients with chronic stable angina. The TIBET Study Group. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:104–112. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2805–2816. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, et al. The global burden of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Circulation. 2014;129(14):1493–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold SV, Morrow DA, Lei Y, et al. Economic impact of angina after an acute coronary syndrome: insights from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(4):344–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.829523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(38):2949–3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tendera M, Fox K, Ferrari R, et al. Inadequate heart rate control despite widespread use of beta-blockers in outpatients with stable CAD: findings from the international prospective CLARIFY registry. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(1):119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steg PG, Ferrari R, Ford I, et al. Heart rate and use of beta-blockers in stable outpatients with coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalra PR, Morley C, Barnes S, et al. Discontinuation of beta-blockers in cardiovascular disease: UK primary care cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167(6):2695–2699. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiFrancesco D. Funny channels in the control of cardiac rhythm and mode of action of selective blockers. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53(5):399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amosova E, Andrejev E, Zaderey I, Rudenko U, Ceconi C, Ferrari R. Efficacy of ivabradine in combination with beta-blocker versus uptitration of beta-blocker in patients with stable angina. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2011;25(6):531–537. doi: 10.1007/s10557-011-6327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tardif JC, Ponikowski P, Kahan T, et al. Effects of ivabradine in patients with stable angina receiving β-blockers according to baseline heart rate: an analysis of the ASSOCIATE study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(2):789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karpov YuA, Glezer MG, Vasyuk YuA, Saygitov RT, Shkolnik EL. Antianginal effectiveness and tolerability of ivabradine in patients with stable angina: CONTROL-2 study results. Cardiovasc Ther Prev. 2011;10(8):83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez-Sendon J, Swedberg K, McMurray J, et al. Expert consensus document on beta-adrenergic receptor blockers. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1341–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heusch G. Heart rate in the pathophysiology of coronary blood flow and myocardial ischaemia: benefit from selective bradycardic agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(8):1589–1601. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camici PG, Gloekler S, Levy BI, et al. Ivabradine in chronic stable angina: effects by and beyond heart rate reduction. Int J Cardiol. 2016;15(215):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heusch G, Skyschally A, Schulz R. Cardioprotection by ivabradine through heart rate reduction and beyond. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2011;16(3–4):281–284. doi: 10.1177/1074248411405383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heusch G, Skyschally A, Gres P, Van Caster P, Schilawa D, Schulz R. Improvement of regional myocardial blood flow and function and reduction of infarct size with ivabradine: protection beyond heart rate reduction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2265–2275. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinbongard P, Gedik N, Witting P, Freedman B, Klocker N, Heusch G. Pleiotropic, heart rate-independent cardioprotection by ivabradine. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:4380–4390. doi: 10.1111/bph.13220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skalidis EI, Hamilos MI, Chlouverakis G, Zacharis EA, Vardas PE. Ivabradine improves coronary flow reserve in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tagliamonte E, Cirillo T, Rigo F, et al. Ivabradine and bisoprolol on doppler-derived coronary flow velocity reserve in patients with stable coronary artery disease: beyond the heart rate. Adv Ther. 2015;32:757–767. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tardif JC, Ponikowski P, Kahan T, ASSOCIATE Study Investigators Efficacy of the I(f) current inhibitor ivabradine in patients with chronic stable angina receiving beta-blocker therapy: a 4-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(5):540–548. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koester R, Kaehler J, Ebelt H, Soeffker G, Werdan K, Meinertz T. Ivabradine in combination with beta-blocker therapy for the treatment of stable angina pectoris in every day clinical practice. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99(10):665–672. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werdan K, Perings S, Köster R, et al. Effectiveness of ivabradine treatment in different subpopulations with stable angina in clinical practice: a pooled analysis of observational studies. Cardiology. 2016;135(3):141–150. doi: 10.1159/000447443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder DH, Pauriah M, Lang CC, et al. Is there a Failure to Optimize theRapy in anGina pEcToris (FORGET) study? QJM. 2010;103(5):305–310. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glezer MG, Saygitov RT. Antianginal efficacy and tolerability of ivabradine in the treatment of patients with stable angina: results of CONTROL study. Kardiologia. 2010;11:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.