Abstract

This article reviews current literature on the role of pharmacists in the transition of care (TOC) for patients with heart failure (HF) and the impact of their contributions on therapeutic and economic outcomes. Optimizing the TOC for patients with HF from the hospital to the community/home is crucial for improving outcomes and decreasing high rates of hospital readmissions, which are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and costs. A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of patients with HF facilitates the transition from the hospital to the ambulatory care setting, allowing for the consideration of medical, pharmacological, and lifestyle variables that impact the care of individual patients. Pharmacist participation on both inpatient and outpatient teams can provide a variety of services that have been shown to reduce hospital readmission rates and benefit patient management and treatment. These include medication reconciliation, patient education, medication dosage titration and adjustment, patient monitoring, development of disease management pathways, promotion of medication adherence, and postdischarge follow-up. In addition, as new pharmacologic treatments for HF become available, pharmacists can raise awareness of optimal drug use by maximizing education related to efficacy (e.g., adherence) and safety (e.g., potential side effects and drug interactions). Improving understanding of HF and its treatment will enable increased pharmacist involvement in the TOC that should lead to improved outcomes and reduced healthcare costs.

Funding: Novartis.

Keywords: Cardiology, Care transitions, Healthcare quality, Heart failure, Medication adherence, Medication reconciliation, Medication therapy management, Multidisciplinary care, Patient care team, Sacubitril/valsartan

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) affects approximately 6 million adults in the USA, with more than $30 billion in associated annual costs; by 2030, these figures are expected to rise to more than 8 million adults and more than $69 billion [1]. From 2012 to 2014, the age-adjusted rate of HF-related deaths per 100,000 people increased from 81.4 to 84.0 [2].

Individuals with HF are broadly classified into two groups based on their left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) values: HF with preserved EF (HFpEF) and HF with reduced EF (HFrEF); the prevalence of each is approximately 50% [3]. The 2013 ACCF/AHA (American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association) Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure defines HFrEF as HF with an EF ≤ 40% and HFpEF as HF with an EF ≥ 50%, with subcategories of HFpEF borderline (EF 41–49%) and HFpEF improved (EF > 40% in patients with previous HFrEF) [3]. Demographics, comorbidities, prognoses, and responses to treatment may differ between HFpEF and HFrEF, leading to distinct treatment and management needs [3].

Direct medical costs account for more than two-thirds of the total cost for HF, with hospital readmissions substantially driving these costs [4, 5]. HF was the leading cause of 30-day readmissions for Medicare patients in 2011, costing $1.75 billion [6]. To reduce the frequency of readmissions, the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a rule in October 2012 that reduces payments to hospitals with excess 30-day readmission rates for HF (among other conditions) [7]. Consequently, healthcare providers are increasing their efforts to ensure that patients with HF receive the correct medications and adhere to treatment regimens following discharge [8]. However, for patients with HF, medication reconciliation can be challenging, mainly because of the complex guidelines for treating HF (and related comorbidities), which can require 6–9 medications at discharge [9–13]. Such complexity may impact medication adherence and introduce the potential for medication errors, both of which may precipitate hospital readmission [12, 14]. Patients with HF and concomitant comorbidities are particularly vulnerable to rehospitalization [15, 16].

Gaps in the transition of care (TOC) for patients with HF must be addressed during the peri- and postdischarge periods. These include provider assessment of the patient prior to discharge (failure to recognize worsening status or evaluate/address comorbidities); provision of information to patients and caregivers on the risks of medication errors and adverse drug events (failure to provide adequate patient/caregiver education); handoff communication between the hospital and the primary care provider (PCP), home healthcare team, and patient (lack of or poor communication); and discharge planning (e.g., medication errors, patient lack of adherence to self-care, lack of or poor follow-up care) [14]. As such, a multidisciplinary team is needed to provide an integrated approach to patient care [14, 17]. Hospital- and clinic-based pharmacists with advanced training in HF, as well as community pharmacists, are important members of this team. The pharmacist’s role in the care of patients with HF includes medication reconciliation and education; medication initiation; dosage titration, adjustment, and monitoring; developing disease management pathways; and posthospital discharge follow-up, clinic, and home visits [18]. The aim of this article is to review strategies to improve HF TOC using pharmacists (and pharmacist-led interventions) as integral members of the multidisciplinary team. This article does not contain any new studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Pharmacist Participation in TOC for Patients with HF Improves Outcomes

Numerous studies have shown that community-based pharmacists, as part of multidisciplinary TOC teams, can improve outcomes for patients with HF [10, 19–25]. The impact of pharmacist intervention was evaluated in a pharmacy-led TOC program for patients with HF from a US hospital [25]. Admission medication reconciliation and discharge medication review were performed to monitor for appropriateness and dosing, duplications, omissions, and drug interactions. Since its initiation, the program has increased compliance with HF core measures (including appropriate medication use) and reduced HF readmissions, 30-day readmissions, all-cause readmissions, and costs [25]. Similarly, implementation of a care-transition pharmacist in a community hospital to address medication-related issues that contributed to readmissions for patients discharged with diagnoses of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or HF showed that receipt of a follow-up phone call from the care-transition pharmacist within 72 h after discharge led to a significantly lower overall 30-day acute care services use rate of 22% (vs 42% for those who did not receive a phone call; P = 0.01) and a 48% lower likelihood of requirement for acute-care services within 30 days of discharge (risk ratio = 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.33–0.82) [26].

In 2007, the impact of active pharmacy intervention (i.e., baseline medication history review; patient-centered counseling; monitoring of adherence, healthcare encounters, and body weight; and as-needed communication with other clinicians) compared with usual care (i.e., rotating pharmacists without specialized training distributing patient medication) was investigated in a 9-month randomized study in outpatients with HF [22]. Intervention significantly improved patient adherence to taking, scheduling, and refilling cardiovascular medications; decreased hospital admissions or emergency department visits; and decreased healthcare utilization and costs [22]. In the randomized, controlled Pharmacist in Heart Failure Assessment Recommendation and Monitoring (PHARM) study, the effects of adding a clinical pharmacist to an HF management team providing outpatient clinic service were explored [19]. Patients who received pharmacist intervention had reduced rates of all-cause mortality and nonfatal HF events (hospitalizations and emergency department visits for HF) compared with patients who received usual follow-up care (4/90 vs 16/91, respectively; odds ratio = 0.22; 95% CI 0.07–0.65; P = 0.005). The intervention group was also closer to the optimal angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) dosage at 6 months of follow-up compared with the usual-care group (P < 0.001) [19]. In an assessment of clinical pharmacist intervention in an outpatient HF clinic, pharmacist-provided assistance with HF medication titrations increased the proportion of patients who achieved optimal ACEI, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), and β-blocker dosages [20].

Community pharmacists can also work successfully with hospitals during TOC of patients with HF [21]. CMS Part D Medication Therapy Management (MTM) programs require prescription drug plan sponsors to optimize medication-related aspects of patient care in collaboration with licensed and practicing pharmacists and physicians; however, pharmacists can bill for counseling patients who have multiple chronic diseases (including HF), take several medications, and pay high costs for their prescriptions [27, 28]. One recent study found that involving a community pharmacist in MTM services at discharge significantly reduced 30-day hospital readmission rates from 20% to 7% (P = 0.017) and improved adherence to medication and self-care [21]. Similar outcomes were observed when pharmacists individualized medication and disease-state counseling, ensured correct medications at discharge, and provided follow-up reminders and counseling [10, 23].

Key Factors in HF TOC Managed by Clinical Pharmacists

Clinical pharmacists are critical team members and are well positioned to be involved in HF TOC in both the inpatient and outpatient settings [17]. As recommended by the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA) and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, clinical pharmacists must routinely identify and resolve common drug-related problems to improve outcomes in patients with HF (Table 1) [5]. In a pharmacist-led medication reconciliation project, an average of seven medication discrepancies were found per patient with HF during hospitalization and at discharge [29]. Incorporating pharmacist review as a standard practice during and after hospitalization can identify errors for correction, thereby reducing the risk of adverse drug events [30–33]. In the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study, which evaluated an intervention consisting of medication reconciliation at admission and discharge, counseling early in hospitalization and at discharge, and a follow-up call after discharge, medication reconciliation was identified as the most important component of the intervention to improve TOC [31]. A pooled analysis of two randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of pharmacist intervention in patients with HF or hypertension showed that the risk of adverse drug events and medication errors was reduced by 35% and 37%, respectively, compared with controls (adverse drug events risk ratio 0.65; 95% CI 0.47–0.90; medication errors risk ratio, 0.63; 95% CI 0.40–0.98) [32].

Table 1.

Common drug-related problems in patients with heart failure.

Reprinted from Journal of Cardiac Failure, 19(5), Milfred-LaForest SK et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, 354–369, Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier [5]

| Problem | Patient indicated for a treatment who |

|---|---|

| Lack of treatment | Is not receiving the treatment |

| Suboptimal treatment | Is receiving the wrong medication |

| Undertreatment | Is receiving a subtherapeutic dose |

| Inaccessible treatment | Is unable to obtain medication |

| Overdose | Is receiving a toxic dose |

| Adverse reaction to treatment | Is receiving an indicated dose and experiences treatment-related side effects |

| Drug interaction | Is receiving an indicated dose and experiences side effects due to interactions with other treatments or dietary components |

| Off-label use | Has no FDA-approved indication for the treatment being used |

FDA Food and Drug Administration

Improper use of medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, calcium channel blockers (in patients with HFrEF), and antiarrhythmic agents, can exacerbate HF symptoms and result in hospitalization [12]. It is important for providers to be aware of medications that are contraindicated in patients with HF (Table 2) and inquire about patient use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and nonprescription therapies [34–37]. One study observed that the rates of CAM use were 31% in women and 12% overall [38]. Another study found rates of herbal medication and other nonprescription therapies of approximately 20% each and over-the-counter medication use of greater than 75% [39]. Furthermore, with the approval of novel medications for HF, such as the ARB/neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) combination therapy, sacubitril/valsartan, and the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel blocker ivabradine, pharmacists must monitor appropriate use of these with other HF medications [40, 41]. ARNIs are recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic HFrEF and to replace ACEIs or ARBs in patients with chronic, symptomatic HFrEF and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II/III [40, 42]. Sacubitril/valsartan cannot be used concomitantly in patients taking ACEIs (requires a washout of ≥ 36 h), in people with diabetes taking aliskiren, and in pregnancy [40]. Ivabradine is recommended to reduce risk of hospitalization in patients with symptomatic (NYHA class II/III), stable, chronic HFrEF (EF < 35%) who are in sinus rhythm with a resting heart rate of ≥ 70 bpm and receiving guideline-directed evaluation and management (GDEM, including a β-blocker at maximum tolerated dose) [41, 42]. The use of ivabradine with other negative chronotropes requires monitoring because of an increased risk for bradycardia, and it cannot be used in patients with blood pressure measurements < 90/50 mmHg, resting heart rates < 60 bpm, or demand pacemakers set to rates ≥ 60 bpm [41]. Pharmacists can also educate the healthcare team about new medications and their uses (e.g., recommendations for starting dosages and dose titration), including how to identify which patients should receive them. Recent guideline updates, such as the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure, provide key information from professional clinical organizations for the appropriate and meaningful incorporation of new agents into routine practice [42, 43].

Table 2.

Medications contraindicated in patients with heart failure.

(Adapted from Amabile 2004 and Page 2016—Source: American Heart Association, Inc) [34–37]

| Medication/medication class | Recommendation | Primary reasons for contraindication/caution |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | Conservative use; lowest doses | Sodium and fluid retention |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Avoid in patients with symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction |

Sodium and water retention Compromise effects of diuretics Increase systemic vascular resistance |

| Antiarrhythmic agents (class I and III, excluding amiodarone) |

Avoid all class I agents Avoid ibutilide and sotalol |

Negative inotropic activity Proarrhythmic effects |

| Antihypertensive agents | ||

| α1-antagonists | Do not use | Cardiac hypertrophy |

| Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | Avoid use |

Negative inotropic activity Neurohormonal activation |

| Minoxidil | Avoid use |

Fluid retention Stimulation of RAAS |

| Antihyperglycemic agents | ||

| Metformin | Avoid use in patients with NYHA class III/IV symptoms and those with previous hospitalization for HF exacerbations; conservative use with monitoring in others | Increased anaerobic glucose metabolism and lactate elevation |

| Alogliptin and saxagliptin | Avoid use in patients who develop signs and symptoms of HF, especially if the patient has CV or renal disease at baseline | Unknown |

| Thiazolidinediones | Avoid use in patients with NYHA class III/IV symptoms; monitor for new or increased HF symptoms in others | Fluid retention |

| Hematologic medications | ||

| Anagrelide | Avoid |

Positive inotropic activity Tachycardia |

| Cilostazol | Do not use | Inhibition of phosphodiesterase III |

| Neurologic and psychiatric medications | ||

| Amphetamines | Avoid use |

Peripheral α- and β-agonist activities Tachycardia, arrhythmia |

| Carbamazepine | Avoid if possible; use other first-line agents |

Negative inotropic and chronotropic effects Suppression of sinus nodal automaticity and atrioventricular conduction Anticholinergic effects |

| Clozapine | Actively monitor for new or increased HF symptoms | Unknown |

| Ergot alkaloids | Avoid use if possible; if used, monitor regularly for new murmurs |

Increased serum norepinephrine Excess serotonin activity |

| Pergolide | Avoid use if possible | Excess serotonin levels |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Avoid if possible; use other first-line agents |

Negative inotropic effects Increase in automaticity Slowing of intracardiac conduction Proarrhythmic |

| Miscellaneous medications | ||

| β2-agonists | Avoid long-term systemic administration |

Direct positive chronotropic effect Hypokalemia |

| Herbal medications | Avoid |

Unknown; lack of data for most Increased risk of bleeding Hypertension Sodium retention |

| Itraconazole | Avoid | Negative inotropic activity |

| Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim | Avoid in patients taking an ACEi or ARB | Risk of hyperkalemia and sudden death |

| Theophylline | Avoid use in decompensated HF | Increased theophylline levels and toxicity |

| TNF-α inhibitors | Avoid if new-onset or worsening HF symptoms develop; infliximab doses of > 5 mg/kg contraindicated | Cytokine-mediated myocardial toxicity |

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, CV cardiovascular, HF heart failure, NYHA New York Heart Association, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor alpha

The pharmacy team should consider several factors during the HF TOC: (1) general patient physical assessment; (2) medication regimens and laboratory test results; (3) pharmacotherapeutic management to ensure that patients receive dose-optimized GDEM with limited adverse effects; (4) potential for drug–drug or drug–condition interactions; (5) other medication-related issues, including perceived versus absolute contraindications; and (6) type (or lack) of insurance coverage and out-of-pocket medication costs, and possible less expensive alternatives [11, 30, 44, 45]. The requirements for MTM programs are generally aligned with these considerations [27]. Overall, the pharmacist should ensure that all prescribed medications are for approved indications and patients receive clear and practical instructions for dosage and administration, including duration of therapy [44].

Impact of Pharmacists Counseling Patients During TOC

In the PILL-CVD study, intervention incorporating early initial inpatient pharmacist consultation was found to be useful for obtaining background and baseline information, building relationships, and facilitating discharge counseling [31]. During an initial consultation, pharmacists can gauge the patient’s level of understanding to individualize education and correct misunderstandings [29]. Discharge counseling can also help patients understand their new medication regimen. In the PILL-CVD study, discharge counseling included reviewing medications, establishing a plan for filling new prescriptions, identifying potential barriers to adherence, provision of adherence aids, and “teach-back” methods to ensure patient understanding [31]. Pharmacists noted the importance of emphasizing the difference between regimens at admission and postdischarge, particularly when using the same drug at a different dosage [31].

Face-to-face interactions with pharmacists can be beneficial for inpatients and outpatients and may lead to reduced readmission rates [12, 21, 46–48]. A pooled data analysis from 10 randomized clinical trials showed that HF management programs which provide in-person communication/education reduced hospital readmissions significantly (2.5%; P < 0.001) compared with usual care [49].

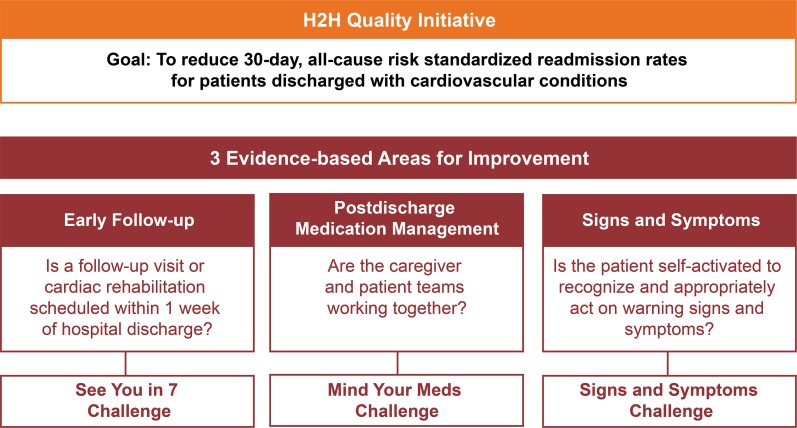

The recently introduced ACC Patient Navigator Program aims to reduce readmission by providing personalized support to patients as they face challenges associated with HF hospitalization and TOC [49]. The ACC also developed the Hospital to Home Initiative (Fig. 1) that provides resources to improve TOC and reduce HF readmission rates [50].

Fig. 1.

Overview of the American College of Cardiology’s Hospital to Home (H2H) Project [66]

Unique Roles of the Pharmacy Team in Improving Patient Health

Collaborative-care models that include pharmacists have been shown to reduce all-cause and HF-related hospitalizations and to improve overall patient health and satisfaction [12, 51]. Studies in inpatient settings have shown positive effects of clinical pharmacist collaborations with HF teams, including improving physician adherence to GDEM [12, 30, 51]. Clinical pharmacists can serve as valuable consultants to providers [30]. Communication delays can be prevented and recommended drug therapy can be implemented effectively via email communication between clinical pharmacists and providers [52]. In our experience, attention to comments made by the inpatient team (e.g., pending laboratory testing and follow-up instruction comments) can be especially helpful to ambulatory care pharmacists when developing patient-specific plans and goals.

Similarly, pharmacist collaboration with outpatient HF clinicians can improve medication recommendations, assessments, and education [51]. Community pharmacists can provide services to facilitate the TOC [53]. A Scottish study found that cognitive HF services by community pharmacists were well received by patients and improved their understanding of the conditions and medications, medication adherence, and self-care [54]. Initial consultation reviewed each HF medication (e.g., how and why taken, adherence issues), patient perceptions and understanding of side effects, identification and assessment of HF symptoms, importance of monitoring weight, and smoking status; answered patient questions; and formulated an action plan to resolve any problems, which included referral to other clinicians if needed. Follow-up consultation assessed HF symptom changes, reviewed previously discussed problems and the actions taken to address them, discussed care outcomes, and referred patients to other clinicians if needed [54]. Team-based care involving a pharmacist is essential to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s patient-centered medical home model [55].

Strategies to Encourage Adherence

The often-complicated HF treatment regimens may compromise adherence, of which pharmacists may promote using various strategies. In a randomized controlled trial that compared 9 months of active pharmacist intervention and 3 months of follow-up assessment with usual care for low-income patients with HF, medication adherence during this timeframe was higher among those who received active intervention compared with patients who did not (78.8%; 95% CI 74.9–82.7 vs 67.9%; 95% CI 63.8–72.1, respectively) [22].

Adherence is significantly worse among patients with inadequate versus adequate health literacy; however, pharmacist intervention that includes patient education, therapeutic monitoring, and communication with PCPs can substantially improve adherence in these patients [56]. Techniques such as determining whether the patient comprehends pill-bottle label instructions can encourage adherence [31]. Available tools that facilitate health literacy assessment throughout the TOC process are listed in Table 3 [57–59].

Table 3.

| Tool | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| REALM | Can be administered in < 3 min | Does not measure understanding |

| Requires minimal training | Estimates may be more affected by response bias than on S-TOFHLA | |

| Most commonly used in clinical settings | Contains 66 items | |

| TOFHLA | Measures health information comprehension | Administration requires up to 22 min |

| Is used as the gold standard for comparison of new tools | ||

| S-TOFHLA | Measures health information comprehension | Categorizes individuals as having “inadequate skills” at almost 2 times the rate of REALM, possibly because it may be less accurate at measuring prior knowledge compared with REALM |

| Administration requires 7–8 min | ||

| Commonly used in clinical settings | ||

| NVS | Has a high sensitivity for detecting limited health literacy | Because of its high sensitivity, it is not as useful as other tests in a research setting, when precision is required |

| Can be administered in < 3 min |

NVS newest vital sign, REALM rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine, S-TOFHLA short test of functional health literacy in adults, TOFHLA test of functional health literacy in adults

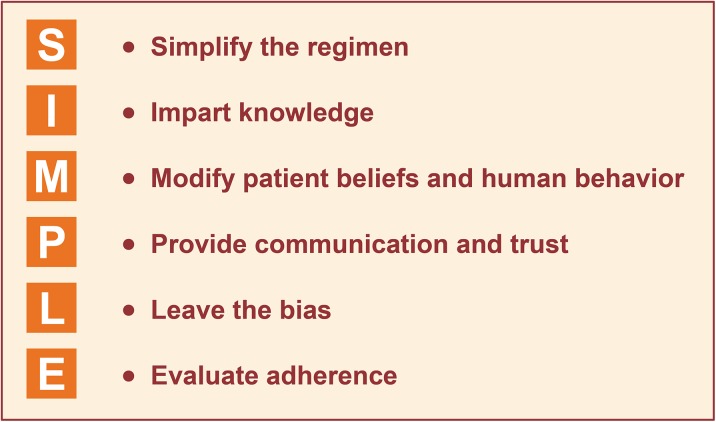

Other predictors of suboptimal adherence of which pharmacists should be aware include nonwhite race, younger age, more-severe HF and comorbidities, depression, smoking status, previous nonadherence, living alone, Medicaid insurance, lack of insurance, and medication regimens that require frequent dosing or disruption of the patient’s daily activities [13, 60]. Addressing adherence issues starts with identifying patients with a history of or risk factors for poor adherence. Pharmacists in the PILL-CVD study reported that the most useful question at initial consultation was how many days the patient missed taking one (or more) of the medications during the week prior to hospitalization, because it helped identify the history, nature, and consequences of nonadherence [31]. Identification of adherence barriers allows for the initiation of strategies to overcome them, as exemplified by the SIMPLE approach (Fig. 2) [61]. Pharmacist interventions, including use of adherence aids, have been shown to substantially improve adherence [56]. In addition, an illustrated medication schedule can help patients fill their pillboxes correctly [31].

Fig. 2.

Strategies to improve adherence: the SIMPLE approach [61]

Strategies to Improve Current Limitations of Treatment Transitions

Mobile health (mHealth) approaches (e.g., the use of instant messaging or text messaging interventions to communicate with patients) can improve self-care following hospital discharge. HF self-management was improved with an intervention in which patients began receiving text messages regarding medication, dietary, and appointment adherence; HF symptom recognition; health management to address symptoms; and healthcare navigation the day after hospital discharge [62]. Mobile health tools have been used in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) to promote medication adherence, improve weight management, increase physical activity, aid smoking cessation, facilitate self-management of diabetes mellitus, and improve hypertension and dyslipidemia care [63]. In addition, the AHA has developed a self-check plan for tracking symptoms, a “Questions to Ask Your Doctor” document, and numerous heart health trackers (e.g., activity, blood pressure, and healthcare team trackers) [64].

Social determinants of health identified as influencing the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of CVD include socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, social support, culture/language, access to care, and residential environment [65]; these factors also impact the success of the TOC process. For example, in the text messaging intervention study described above, almost one-quarter of low-income patients did not have access to personal cell phones and most did not have smartphones; thus, such patients are less likely to benefit from mHealth approaches [62]. It has been suggested that providing low-income patients with cell phones could be cost-effective for improving patient accessibility and outcomes [62].

Conclusions

Heart failure is one of the most common and costly diseases in the USA, and the number of HF-related deaths is increasing. Pharmacists are integral to multidisciplinary TOC teams in HF. During the transition from hospital to ambulatory home- or community-based care, pharmacy services (including medication reconciliation, identification and prevention of adverse drug events, suggestions for improving medication access, and patient education) can improve outcomes and decrease the risk for rehospitalization. Cohesive multidisciplinary team approaches can improve medication adherence and provide a trusted resource for patients’ questions. Novel technologies and expanded access to pharmacy services can improve current limitations of transitional care in HF and other chronic diseases.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The review, article processing charges, and open access fee were funded by Novartis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval to the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Marcel Kuttab, PharmD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Inc. Support for this assistance was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Disclosures

Sarah L. Anderson and Joel C. Marrs have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.5853495.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ni H, Xu JQ. Recent trends in heart failure-related mortality: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS data brief, no 231. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db231.htm. Accessed 13 Oct 2016. [PubMed]

- 3.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–e319. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milfred-Laforest SK, Chow SL, Didomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. J Card Fail. 2013;19:354–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hines AL, Barrett ML, Jiang HJ, Steiner CA. Conditions with the largest number of adult hospital readmissions by payer, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #172. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb172-Conditions-Readmissions-Payer.jsp. Accessed 5 Oct 2016. [PubMed]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

- 8.Kitts NK, Reeve AR, Tsu L. Care transitions in elderly heart failure patients: current practices and the pharmacist’s role. Consult Pharm. 2014;29:179–190. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2014.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray MD. Implementing pharmacy practice research programs for the management of heart failure. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:546–548. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salas CM, Miyares MA. Implementing a pharmacy resident run transition of care service for heart failure patients: effect on readmission rates. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(11 Suppl 1):S43–S47. doi: 10.2146/sp150012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodgers JE, Stough WG. Underutilization of evidence-based therapies in heart failure: the pharmacist’s role. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:18S–28S. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.4part2.18S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalisch LM, Roughead EE, Gilbert AL. Improving heart failure outcomes with pharmacist-physician collaboration: how close are we? Future Cardiol. 2010;6:255–268. doi: 10.2217/fca.09.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MJ, Shaykevich S, Cawthon C, Kripalani S, Paasche-Orlow MK, Schnipper JL. Predictors of medication adherence postdischarge: the impact of patient age, insurance status, and prior adherence. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:470–475. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gheorghiade M, Vaduganathan M, Fonarow GC, Bonow RO. Rehospitalization for heart failure: problems and perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng RK, Cox M, Neely ML, et al. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction in the Medicare population. Am Heart J. 2014;168:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mentz RJ, Kelly JP, von Lueder TG, et al. Noncardiac comorbidities in heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2281–2293. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper LB, Hernandez AF. Assessing the quality and comparative effectiveness of team-based care for heart failure: who, what, where, when, and how. Heart Fail Clin. 2015;11:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng JW, Cooke-Ariel H. Pharmacists’ role in the care of patients with heart failure: review and future evolution. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:206–213. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gattis WA, Hasselblad V, Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM. Reduction in heart failure events by the addition of a clinical pharmacist to the heart failure management team: results of the Pharmacist in Heart Failure Assessment Recommendation and Monitoring (PHARM) Study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1939–1945. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.16.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszczuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70:1070–1076. doi: 10.2146/ajhp120267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luder HR, Frede SM, Kirby JA, et al. TransitionRx: impact of community pharmacy postdischarge medication therapy management on hospital readmission rate. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;2015(55):246–254. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, et al. Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:714–725. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warden BA, Freels JP, Furuno JP, Mackay J. Pharmacy-managed program for providing education and discharge instructions for patients with heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:134–139. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadik A, Yousif M, McElnay JC. Pharmaceutical care of patients with heart failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:183–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunadi S, Upfield S, Pham ND, Yea J, Schmiedeberg MB, Stahmer GD. Development of a collaborative transitions-of-care program for heart failure patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:1147–1152. doi: 10.2146/ajhp140563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fera T, Anderson C, Kanel KT, Ramusivich DL. Role of a care transition pharmacist in a primary care resource center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:1585–1590. doi: 10.2146/ajhp130684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medication Therapy Management. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/MTM.html. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

- 28.Odum L, Whaley-Connell A. The role of team-based care involving pharmacists to improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes. Cardiorenal Med. 2012;2:243–250. doi: 10.1159/000341725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson CA. Integrated pharmacy practice helps reduce heart failure readmission rate. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69:1540–1541. doi: 10.2146/news120066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coons JC, Fera T. Multidisciplinary team for enhancing care for patients with acute myocardial infarction or heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:1274–1278. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haynes KT, Oberne A, Cawthon C, Kripalani S. Pharmacists’ recommendations to improve care transitions. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1152–1159. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray MD, Ritchey ME, Wu J, Tu W. Effect of a pharmacist on adverse drug events and medication errors in outpatients with cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:757–763. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eggink RN, Lenderink AW, Widdershoven JW, van den Bemt PM. The effect of a clinical pharmacist discharge service on medication discrepancies in patients with heart failure. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:759–766. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9433-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amabile CM, Spencer AP. Keeping your patient with heart failure safe: a review of potentially dangerous medications. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:709–720. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Page RL, 2nd, O’Bryant CL, Cheng D, et al. Drugs that may cause or exacerbate heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e32–e69. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentry CA, Nguyen AT. An evaluation of hyperkalemia and serum creatinine elevation associated with different dosage levels of outpatient trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole with and without concomitant medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:1618–1626. doi: 10.1177/1060028013509973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dal Negro R, Turco P, Pomari C, Monici-Preti P. Effect of various disease states on theophylline plasma levels and on pulmonary function in patients with chronic airway obstruction treated with a sustained release theophylline preparation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1987;25:401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez-Sellés M, García Robles JA, Muñoz R, et al. Pharmacological treatment in patients with heart failure: patients knowledge and occurrence of polypharmacy, alternative medicine and immunizations. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dal Corso E, Bondiani AL, Zanolla L, Vassanelli C. Nurse educational activity on non-prescription therapies in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007;6:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Entresto (sacubitril and valsartan) [prescribing information]. East Hanover: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2015.

- 41.Corlanor (ivabradine) [prescribing information]. Thousand Oaks: Amgen; 2015.

- 42.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1476–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136:e137–e161. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bucci C, Jackevicius C, McFarlane K, Liu P. Pharmacist’s contribution in a heart function clinic: patient perception and medication appropriateness. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardioselective β-blockers in patients with reactive airway disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:715–725. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-9-200211050-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doucette D, Goodine C, Symes J, Clarke E. Patients’ recall of interaction with a pharmacist during hospital admission. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66:171–176. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v66i3.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slack LR, Ing L. Prevalence and satisfaction of discharged patients who recall interacting with a pharmacist during a hospital stay. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62:204–208. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morecroft CW, Thornton D, Caldwell NA. Inpatients’ expectations and experiences of hospital pharmacy services: qualitative study. Health Expect. 2015;18:1009–1017. doi: 10.1111/hex.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schell W. A review: discharge navigation and its effect on heart failure readmissions. Prof Case Manag. 2014;19:224–234. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American College of Cardiology. Quality improvement for institution. Hospital to Home. http://cvquality.acc.org/Initiatives/H2H.aspx. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

- 51.Koshman SL, Charrois TL, Simpson SH, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT. Pharmacist care of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:687–694. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lekura J, Tita C, Lanfear DE, Williams CT, Jennings DL. Assessing the potential of e-mail for communicating drug therapy recommendations to physicians in patients with heart failure and ventricular-assist devices. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:478–480. doi: 10.1177/0897190013513618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalista T, Lemay V, Cohen L. Postdischarge community pharmacist-provided home services for patients after hospitalization for heart failure. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;2015(55):438–442. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowrie R, Johansson L, Forsyth P, Bryce SL, McKellar S, Fitzgerald N. Experiences of a community pharmacy service to support adherence and self-management in chronic heart failure. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:154–162. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient Centered Medical Home Resource Center. https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

- 56.Noureldin M, Plake KS, Morrow DG, Tu W, Wu J, Murray MD. Effect of health literacy on drug adherence in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:819–826. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Collins SA, Currie LM, Bakken S, Vawdrey DK, Stone PW. Health literacy screening instruments for eHealth applications: a systematic review. J Biomed Inform. 2012;45:598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Variation in estimates of limited health literacy by assessment instruments and non-response bias. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:675–681. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osborn CY, Weiss BD, Davis TC, et al. Measuring adult literacy in health care: performance of the newest vital sign. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S36–S46. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis EM, Packard KA, Jackevicius CA. The pharmacist role in predicting and improving medication adherence in heart failure patients. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:741–755. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.7.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.American College of Preventive Medicine. Medication adherence—improving health outcomes. http://www.acpm.org/?MedAdhereTTProviders#. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

- 62.Nundy S, Razi RR, Dick JJ, et al. A text messaging intervention to improve heart failure self-management after hospital discharge in a largely African–American population: before-after study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e53. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burke LE, Ma J, Azar KM, et al. Current science on consumer use of mobile health for cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:1157–1213. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.American Heart Association. Heart failure tools and resources. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartFailure/Heart-Failure-Tools-Resources_UCM_002049_Article.jsp#. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

- 65.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:873–898. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.American College of Cardiology. Quality improvement for institutions. About H2H. http://cvquality.acc.org/Initiatives/H2H/About-H2H.aspx. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.