Abstract

Background

In the Mediterranean basin, Leishmania infantum is a major cause of disease in dogs, which are frequently co-infected with other vector-borne pathogens (VBP). However, the associations between dogs with clinical leishmaniosis (ClinL) and VBP co-infections have not been studied. We assessed the risk of VBP infections in dogs with ClinL and healthy controls.

Methods

We conducted a prospective case-control study of dogs with ClinL (positive qPCR and ELISA antibody for L. infantum on peripheral blood) and clinically healthy, ideally breed-, sex- and age-matched, control dogs (negative qPCR and ELISA antibody for L. infantum on peripheral blood) from Paphos, Cyprus. We obtained demographic data and all dogs underwent PCR on EDTA-blood extracted DNA for haemoplasma species, Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp., Babesia spp., and Hepatozoon spp., with DNA sequencing to identify infecting species. We used logistic regression analysis and structural equation modelling (SEM) to evaluate the risk of VBP infections between ClinL cases and controls.

Results

From the 50 enrolled dogs with ClinL, DNA was detected in 24 (48%) for Hepatozoon spp., 14 (28%) for Mycoplasma haemocanis, 6 (12%) for Ehrlichia canis and 2 (4%) for Anaplasma platys. In the 92 enrolled control dogs, DNA was detected in 41 (45%) for Hepatozoon spp., 18 (20%) for M. haemocanis, 1 (1%) for E. canis and 3 (3%) for A. platys. No Babesia spp. or “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” DNA was detected in any dog. No statistical differences were found between the ClinL and controls regarding age, sex, breed, lifestyle and use of ectoparasitic prevention. A significant association between ClinL and E. canis infection (OR = 12.4, 95% CI: 1.5–106.0, P = 0.022) was found compared to controls by multivariate logistic regression. This association was confirmed using SEM, which further identified that younger dogs were more likely to be infected with each of Hepatozoon spp. and M. haemocanis, and dogs with Hepatozoon spp. were more likely to be co-infected with M. haemocanis.

Conclusions

Dogs with ClinL are at a higher risk of co-infection with E. canis than clinically healthy dogs. We recommend that dogs diagnosed with ClinL should be tested for E. canis co-infection using PCR.

Keywords: Canine leishmaniosis, Leishmania infantum, Ehrlichia canis, Vector-borne pathogen, Co-infection, Cyprus, Anaplasma platys, Mycoplasma haemocanis, Hepatozoon spp., Structural equation model

Background

Canine leishmaniosis, caused by the protozoan parasite Leishmania infantum, is transmitted by a phlebotomine sand fly vector [1] and is endemic in Central and South America, Asia and several countries of the Mediterranean basin. An estimated 2.5 million dogs are infected with L. infantum in south-west Europe alone [2]. This potentially fatal protozoal infection of dogs and humans is an ideal example of the “One Health” approach to disease since dogs are the major reservoir of infection for humans [3]. In addition, an increasing number of canine leishmaniosis cases are being reported in non-endemic European countries, such as the UK and Germany, due to pet travel and importation of dogs from endemic areas, making leishmaniosis an emerging disease in these countries [4–6]. There is a risk that it might become endemic in such countries if future climate conditions support the life-cycle of a suitable vector.

Dogs with clinical leishmaniosis (ClinL) are often concurrently infected with multiple pathogens, which are often vector-borne, such as Ehrlichia canis, the causative agent for canine monocytic ehrlichiosis, Anaplasma platys, Babesia vogeli and Hepatozoon canis, resulting in an unpredictable incubation period, atypical clinical outcome and poorer prognosis, compared with dogs infected with L. infantum alone [7, 8]. These vector-borne pathogens (VBP) are transmitted by different vectors to dogs, such as Rhipicephalus sanguineus (for A. platys, E. canis and H. canis), Ixodes ricinus (for Anaplasma phagocytophilum), Ixodes spp. ticks (for Borrelia burgdorferi) and mosquitoes (for Dirofilaria immitis) [9]. While it has been suggested that leishmaniosis is a predisposing factor for infection with other pathogens in dogs, this has not been investigated to date [8, 10].

The aim of this case-control study was to investigate the hypothesis that dogs with ClinL are at greater risk for VBP infections than clinically healthy dogs. In addition, besides the commonly used logistic regression analyses for case-control studies [11], we performed structural equation modelling (SEM), which is an advancement of traditional regression approaches, allowing direct, indirect and co-variance relationships to be assessed simultaneously. The SEM has recently been employed in veterinary studies [12].

Methods

Study design and populations

Through a case-control study design, we evaluated if dogs with ClinL are at a greater risk than healthy controls for VBP infections including Babesia spp., “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” (CMhp), Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp., Hepatozoon spp., and M. haemocanis. All dogs presented as clinical patients to a veterinary centre in Paphos, Cyprus, an area with high prevalence of L. infantum in dogs [13] and endemic for canine VBPs [14].

Eligible cases included dogs naturally infected with ClinL which were diagnosed based on the presence of clinical signs associated with L. infantum infection, and enrolled in the final statistical analysis if they were positive on both quantitative PCR (qPCR) on peripheral blood and serum antibodies for L. infantum. We attempted to match controls to the cases by age, sex and breed as well as, if possible, by lifestyle and the use of ectoparasitic prevention. For ClinL crossbreed dogs, the controls were dogs of similar size and dog group (e.g. terrier, toy or hound group) to the case dog. The control dogs were apparently clinically healthy, and were enrolled in the final statistical analysis if they were negative by both qPCR and antibody serology for L. infantum on peripheral blood.

Data on age, sex (male or female), breed (pedigree or crossbreed), lifestyle (outdoors or mainly indoors), use of ectoparasitic prevention (use or no use) and clinical signs were recorded for each dog. All dogs were examined by the same veterinarian author (CA) and classified as clinically healthy or suffering from ClinL, following The LeishVet Group Guidelines [15]. Exclusion criteria for enrolment in this study included prior vaccination or treatment for leishmaniosis, dogs undergoing therapy with immunosuppressives/chemotherapeutics or dogs less than 6 months old.

Laboratory tests

We obtained blood samples of approximately 2–4 ml in plain and EDTA blood tubes by venepuncture from each dog. The EDTA blood tubes were centrifuged; plasma samples were obtained and transferred in a separate tube. All tubes were frozen at -20 °C until transported on dry ice to the Department of Pathobiology and Population Sciences, The Royal Veterinary College, University of London, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK. For the PCRs, DNA was extracted from 200 μl of EDTA blood using a commercial kit GenEluteTM Blood Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. During extraction, nuclease-free water was used as a negative extraction control. The DNA was eluted with 50 μl of nuclease free water and stored at -20 °C until transported on dry ice to Diagnostic Laboratories, Langford Vets, University of Bristol, UK, for testing.

In order to assess the presence of amplifiable DNA, the absence of PCR inhibitors and correct assay setup, the qPCRs for Leishmania spp. [16], Babesia spp. [17], CMhp and M. haemocanis [18] were duplexed with an internal amplification control (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene), and a threshold cycle (Ct) value of < 30 was used as a cut-off for indication of acceptable DNA. Any samples with Ct values greater than or equal to 30 were excluded from the study due to insufficient quantity/quality of DNA. Conventional PCR assays, as previously described, were used to detect infection with Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp. [19] and Hepatozoon spp. [20]. For each PCR assay, DNA from known infected dogs and nuclease-free water were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

All samples that yielded positive results with the Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp. PCR assay and 1/3 of the positive Hepatozoon spp. samples (a mixture of ClinL cases and controls) were purified using the NucleoSpin PCR and Gel Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, quantified with a Qubit™ fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Paisley, UK) and submitted for DNA sequencing at DNA Sequencing and Services (College of Life Sciences, University of Dundee, Scotland), in both directions using the same primers as those used for the PCR. The forward and reverse DNA sequences were then assembled, and a consensus sequence was searched against the NCBI database using BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) to identify the infecting species.

For the L. infantum serology, sera from cases and controls were transported on dry ice to the Departament de Medicina i Cirurgia Animals, Facultat de Veterinària, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. A L. infantum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as previously described, was used [21]. Each ELISA also included a calibrator serum sample from a dog infected by L. infantum as confirmed by IFAT (IFI Megascreen FLUOLEISH inf, Diagnostik Megacor, Hörbranz, Austria), a commercially available ELISA (Esteve Veterinary Laboratories, Dr Esteva S.A, Barcelona, Spain) and a rapid immunomigratory test (Speedleish, Virbac, La Seyne sur Mer, France). The ELISA also included a positive control serum sample from a dog with confirmed L. infantum infection by IFAT and demonstrating clinical signs associated with Leishmania infection, as well as a negative control serum sample from a cat that was resident in the UK where L. infantum is not endemic. Results were quantified as ELISA units (EU) relative to the calibrator (arbitrarily set at 100 EU). The positive cut-off value had previously been established at 35 EU (mean + 4 standard deviations of values from 80 dogs from a non-endemic area).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the sample size to allow the identification of risk for VBP co-infection in dogs with ClinL as follows. On the basis of the admission frequencies for VBPs in the study’s veterinary centre and previously published data [14, 22–24] the expected proportion of control dogs being exposed to VBPs was estimated at 5%. The power calculation was performed using the on-line EpiTools epidemiological calculator (http://epitools.ausvet.com.au). A sample size of 50 dogs with ClinL and 50 controls was calculated, when the testing hypothesis was set with an odds ratio of 6, a power of 80% and confidence level at 95%. To strengthen the statistical power, we used approximately a 1:2 ratio for matching. We compared the continuous variable (age) between ClinL cases and controls with the Mann-Whitney test and categorical variables (sex, breed, lifestyle, use of ectoparasitic prevention, positivity for A. platys, positivity for E. canis, positivity for Hepatozoon spp. and positivity for M. haemocanis) with the Chi-square test. Independent variables that yielded P-values of < 0.1 in a univariable analysis were then tested in a multivariable logistic regression analysis. Within the final multivariable models a P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for inclusion. Descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows (version 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

We constructed a SEM that reflected the two hypothesised mechanisms associated with ClinL and VBPs infection statuses in domestic dogs: (i) causal effects of host characteristics; and (ii) pathogen interrelationships. We modelled the host characteristics as variables that predicted VBPs status, except ClinL which was controlled for in the sampling design. To estimate VBP interrelationships, including potential pathogen-facilitation, we included pathogen-pathogen covariance in the model. We followed Kline [25] and Rosseel [26], and more recent package advancements available through the R package lavaan (www.lavaan.ugent.be) to check alignment with SEM assumptions. Model fit was assessed using a chi-square statistic, and additionally scrutinized using a root mean square error of approximation and a comparative fit index, as recommended by Kline [25]. We used a diagonally weighted least squares SEM estimator method, which is appropriate for endogenous categorical variables [25, 26]. We present standardised coefficients and covariances enabling comparison among coefficient effect sizes [25, 26]. All SEM analyses were undertaken in the program R version 3.1.2 (www.r-project.org) using the lavaan [26] package.

Results

From March 2013 to April 2014, 53 dogs with ClinL and 103 dog controls were screened for eligibility. We excluded three dogs with ClinL; two were ELISA-positive but qPCR-negative and one was qPCR-positive but ELISA-negative for L. infantum. From the controls dogs 11 were excluded; nine were qPCR-positive and two were ELISA-positive for L. infantum. The age of the 142 dogs enrolled in the case-control study ranged from 1 to 12 years (median 5.6 years, interquartile range 8 years) and 105 (74%) were pedigree. The most common breeds were Segugio Italiano, Cocker Spaniel, German Shepherd, Beagle and German Shorthair Pointer.

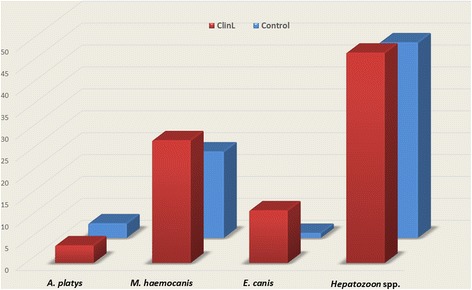

From the 50 enrolled dogs with ClinL, DNA was detected in 24 (48%) for Hepatozoon spp., 14 (28%) for M. haemocanis, 6 (12%) for E. canis and 2 (4%) for A. platys. In the 92 enrolled control dogs, DNA was detected in 41 (45%) for Hepatozoon spp., 18 (20%) for M. haemocanis, 1 (1%) for E. canis and 3 (3%) for A. platys (Fig. 1). Only H. canis was identified following sequencing of Hepatozoon spp. PCR-positive samples. No Babesia spp. or “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” DNA was detected in any dog. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and the PCR results for the VBPs tested.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of VBPs detected by PCR and sequencing between dogs with ClinL (n = 50) and healthy control (n = 92). Abbreviations: VBP, vector-borne pathogen; ClinL, clinical leishmaniosis; A. platys, Anaplasma platys; E. canis, Ehrlichia cani; M. haemocanis, Mycoplasma haemocanis

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study dog groups and PCR/sequencing results for the VBPs tested. All dogs tested negative on quantitative PCR for Babesia spp. and “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum”. The species of A. platys and E. canis were identified following sequencing of PCR products derived from generic Ehrlichia/Anaplasma PCR testing

| Characteristic | No. of cases ClinL (%) (n = 50) | Control (%) (n = 92) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| Median | 3 | 4 |

| Interquartile range | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 (48) | 50 (54) |

| Female | 26 (52) | 42 (46) |

| Lifestyle | ||

| Outoors | 35 (70) | 68 (74) |

| Mainly indoors | 15 (30) | 24 (26) |

| Ectoparasitic prevention | ||

| Used | 17 (34) | 38 (41) |

| Not used | 33 (66) | 54 (69) |

| Breed | ||

| Pedigree | 35 (70) | 70 (76) |

| Crossbreed | 15 (30) | 22 (24) |

| A. platys | ||

| Positive | 2 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Negative | 48 (96) | 89 (97) |

| E. canis | ||

| Positive | 6 (12) | 1 (1) |

| Negative | 44 (88) | 91 (99) |

| Hepatozoon spp. | ||

| Positive | 24 (48) | 41 (45) |

| Negative | 26 (52) | 51 (55) |

| M. haemocanis | ||

| Positive | 14 (28) | 18 (20) |

| Negative | 36 (72) | 74 (80) |

Abbreviations: VBP, vector-borne pathogen; ClinL, clinical leishmaniosis; A. platys, Anaplasma platys; E. canis, Ehrlichia canis; M. haemocanis, Mycoplasma haemocanis

Using multivariable logistic regression analysis, a significant association between ClinL and E. canis infection [odds ratio = 12.4, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.5–106.0, P = 0.022] compared to control dogs was found. We did not identify any association for A. platys, Hepatozoon spp. and M. haemocanis between the two groups. There were no statistically significant differences between the ClinL cases and controls in terms of age, sex, breed, lifestyle, and use of ectoparasitic prevention.

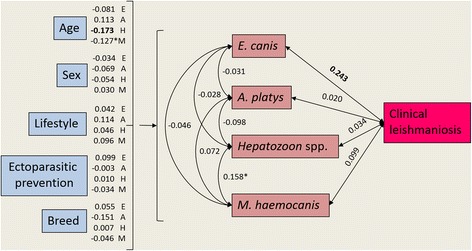

The SEM supported four main associations among variables (Fig. 2, Table 2). Dogs with ClinL were more likely to be co-infected with E. canis, younger dogs were more likely to be infected with each of Hepatozoon spp. and M. haemocanis, although only a trend was identified for the latter, and a trend existed for co-infections between Hepatozoon spp. and M. haemocanis to occur. The SEM showed that there was otherwise negligible evidence of determinants of, or correlations among, VBPs.

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model showing predictors of vector-borne co-infection (except Leishmania infantum), and pathogen covariance (including L. infantum). Values represent standardised coefficients among variables. Single headed arrows represent directional/causal relationships and double headed arrows covariance relationships among pathogens. For image clarity the coefficients of host characteristics predicting pathogens are listed next to each host characteristic. In all cases, except age, variables are binomial (0 or 1) with 1 equal to male, outside, ectoparasitic prevention use, pedigree and positive pathogen status. Significant relationships (P ≤ 0.05) denoted by bold font and trending relationships (P < 0.1) denoted by *. Abbreviations: A. platys, Anaplasma platys; E. canis, Ehrlichia canis; M. haemocanis, Mycoplasma haemocanis. Note: Values represent standardised coefficients among variables. Single headed arrows represent directional/causal relationships and double headed arrows covariance relationships among pathogens. For image clarity the coefficients of host characteristics predicting pathogens are listed next to each host characteristic. In all cases, except age, variables are binomial (0 or 1) with 1 equal to male, outside, ectoparasitic prevention use, pedigree and positive pathogen status. Significant relationships (P ≤ 0.05) denoted by bold font and trending relationships (P < 0.1) denoted by *.

Table 2.

Structural equation model statistical output showing host characteristics predicting infection status for co-infecting pathogens (except Leishmania infantum), and the covariance among pathogens (including L. infantum), in domestic dogs. In all cases, except age, variables are binomial (0 or 1) with 1 equal to male, outside, ectoparasitic prevention use, pedigree and positive pathogen status

| Standardised coefficient/covariance | z-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. canis | |||

| Age | -0.081 | -0.790 | 0.429 |

| Sex | -0.034 | -0.391 | 0.696 |

| Lifestyle | 0.042 | 0.351 | 0.726 |

| Ectoparasite prevention | 0.099 | 0.749 | 0.454 |

| Breed | 0.055 | 0.634 | 0.526 |

| A. platys | |||

| Age | 0.113 | 1.187 | 0.235 |

| Sex | -0.069 | -0.789 | 0.430 |

| Lifestyle | 0.114 | 1.445 | 0.148 |

| Ectoparasitic prevention | -0.003 | -0.028 | 0.978 |

| Breed | -0.151 | -1.161 | 0.246 |

| Hepatozoon spp. | |||

| Age | -0.173 | -1.966 | 0.049 |

| Sex | -0.054 | -0.623 | 0.534 |

| Lifestyle | 0.046 | 0.399 | 0.690 |

| Ectoparasitic prevention | 0.010 | 0.079 | 0.937 |

| Breed | 0.007 | 0.071 | 0.943 |

| M. haemocanis | |||

| Age | -0.127 | -1.650 | 0.099* |

| Sex | 0.030 | 0.348 | 0.728 |

| Lifestyle | 0.096 | 0.921 | 0.357 |

| Ectoparasitic prevention | -0.034 | -0.287 | 0.774 |

| Breed | -0.046 | -0.439 | 0.661 |

| Covariances | |||

| E. canis - Leishmaniosis | 0.243 | 2.303 | 0.021 |

| A. platys - Leishmaniosis | 0.020 | 0.223 | 0.824 |

| Hepatozoon spp. - Leishmaniosis | 0.034 | 0.393 | 0.694 |

| M. haemocanis - Leishmaniosis | 0.099 | 1.115 | 0.265 |

| E. canis - A. platys | -0.031 | -0.889 | 0.374 |

| E. canis - Hepatozoon spp. | -0.028 | -0.312 | 0.755 |

| E. canis - M. haemocanis | -0.046 | -0.598 | 0.550 |

| A. platys - Hepatozoon spp. | -0.098 | -1.130 | 0.258 |

| A. platys - M. haemocanis | 0.072 | 0.647 | 0.517 |

| Hepatozoon spp. - M. haemocanis | 0.158 | 1.761 | 0.078* |

Abbreviations: A. platys, Anaplasma platys; E. canis, Ehrlichia canis; M. haemocanis, Mycoplasma haemocanis

Significant relationships (P ≤ 0.05) denoted by bold font and trending relationships (P < 0.1) denoted by *

Discussion

In this first comprehensive case-control study assessing the risk of VBP co-infection in dogs with leishmaniosis, our key finding shows that dogs with ClinL are 12 times (CI: 1.5–106.0, P = 0.022) more likely to be co-infected with E. canis compared to healthy controls. This further supports the concept of synergism between L. infantum and E. canis during co-infection in dogs in which, as previous studies have suggested, there are more commonly clinical signs (e.g. lymphadenomegaly, splenomegaly, epistaxis, weight loss) [27], more severe haematological changes (e.g. reduced platelet aggregation response, increased activated partial thromboplastin time) [7, 27–29] and hindered clinical improvement during treatment [30] compared to dogs with either ClinL or canine monocytic ehrlichiosis alone.

The pathogenesis behind the speculated synergetic action of L. infantum and E. canis in dogs has not been investigated. Due to the zoonotic nature of canine leishmaniosis there have been extensive studies on the immunopathology of this disease, and it is the best understood canine VBP [9]. It is widely accepted that L. infantum infection promotes a mixed Type 1 T helper (Th1) and Th2 response that will determine the clinical outcome [31], with increased immunosuppressive substances such as interleukin 10, transforming growth factor β and prostaglandin E2 prevailing in dogs with ClinL [32–35]. The suppression of the immune system by these substances could enable reactivation of a previously subclinical E. canis infection or facilitate the establishment of a new E. canis infection in dogs. While little is known regarding the immunopathology of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis, there is evidence of downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules in a macrophage cell line infected with E. canis compared with uninfected macrophages [36]. This downregulation of MHC could impact upon Leishmania infection outcome as MHC class II antigen presentation is likely to be an important mechanism in generating an effective cell mediated response to L. infantum. Furthermore, MHC Class II genotype has been associated with Leishmania specific antibody level and parasite load but not with clinical outcome [37].

In humans there is a well-established synergism between leishmaniasis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [38], with Leishmania causing a more rapid progression to AIDS [39] and HIV increasing the risk of developing fatal visceral leishmaniasis [40]. The immunopathology of this synergistic relationship has been documented to arise due to the co-existence of these two pathogens in macrophages, as well as other cells, triggering complex mechanisms involving cellular-signalling and cytokine production [38, 41, 42]. A similar pathogenesis mechanism could potentially exist between L. infantum and E. canis in dogs, since both microorganisms infect monocytes and macrophages. This hypothetical mechanism is supported by the findings of our clinical case-control study in which an association with ClinL was only found with E. canis co-infection, but not with A. platys, Hepatozoon spp. or M. haemocanis that infect predominantly platelets, neutrophils and erythrocytes, respectively [43–45]. Equally, other mechanisms could orchestrate the pathogenesis of the suspected synergistic relationship between L. infantum and E. canis in dogs. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate how the co-infection of these two pathogens potentially affect the dog’s immune response.

Although, our study is not a cross-sectional epidemiological research project, and the dog population recruited is heavily biased by the inclusion and exclusion criteria, it does provide information for the prevalence of the various VBP tested in the area of Paphos in Cyprus, especially since 65% (92/142) of the samples we collected were from apparently healthy dogs. In the studied population of 142 dogs there is a noticeably high prevalence of Hepatozoon spp. (46%), with H. canis being the only species identified by sequencing, as well as a reasonably high prevalence for M. haemocanis (23%). Similar prevalences have been reported for Hepatozoon spp. and haemoplasmas in the cat population of this island [20], suggesting that the patterns of infection for these two VBP in both the dogs and cats of Cyprus are possibly driven by comparable processes. The prevalence for E. canis of 5% (7/142), and for A. platys of 4% (5/142) in this canine population, are similar to those reported in dogs from other Mediterranean countries [46].

The use of SEM strengthens the findings of our study by confirming the association found between ClinL and E. canis and allowed us to simultaneously investigate the effects of demographic, lifestyle and breed on VBP infection, and the associations between the different VBP. Two additional findings were made. The first one was that dogs infected with Hepatozoon spp. were more likely to be infected with M. haemocanis and, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first time such an association has been reported. This is probably due to the fact that both VBP are suspected to have the same vector R. sanguineus, despite their different routes of transmission: host ingestion of the tick for Hepatozoon spp. transmission and a tick bite for M. haemocanis transmission [44, 47]. Secondly, SEM showed that younger dogs were more likely to be infected with each of Hepatozoon spp. and M. haemocanis, which is in agreement with a previous study on dogs infected with canine haemoplasmas from other Mediterranean countries [48] and could suggest that young animals are more intensively exposed to such VBP.

Limitations of our study include selection and observer bias as this is a case-control study, and the geographical restriction of only including one district of Cyprus. Furthermore, the control dogs were recruited on the basis of being clinically healthy, thus they might not be representative of the general canine population. A multicentre prospective longitudinal study design with follow-up monitoring from birth until death would be ideal, but difficult to implement. Even so, the adequate sample size and conclusions which were based on statistical analysis employing different methodologies should allow some generalisation of our findings to other countries with similar environmental conditions and canine VBP prevalence as Paphos, Cyprus. Studies in the future over longer time periods would be beneficial to investigate the possibility of seasonal effects and to determine if the prognosis of leishmaniosis is different when dogs are also co-infected with E. canis and other VBPs.

Our finding, that dogs with ClinL are at increased risk of E. canis infection compared to healthy dogs, could impact upon the diagnostic and monitoring management of canine leishmaniosis. We recommend that dogs diagnosed with ClinL should be tested for E. canis co-infection using PCR on EDTA peripheral blood [49]. Quantitative serological testing can be considered for the diagnosis of active E. canis infection but should be interpreted appropriately [46]. Whilst we did not perform any follow up on the dogs with ClinL, to further investigate if there is an ongoing increased risk of co-infections during or after the treatment period, we recommend E. canis PCR testing on EDTA peripheral blood if there is clinical or haematological deterioration, such as thrombocytopenia, despite the dog receiving the appropriate anti-Leishmania treatment.

If a dog with ClinL is diagnosed with concurrent E. canis infection, we recommend simultaneous treatment of both infections. For E. canis, the treatment of choice is oral doxycycline at 5 mg/kg twice daily or 10 mg/kg once daily for 4 weeks [46] and for leishmaniosis the appropriate treatment protocol should be based on the clinical stage following The LeishVet Group Guidelines [15]. Furthermore, dogs with ClinL should receive regular and effective protective topical insecticide repellent to prevent infection with E. canis by R. sanguineus and avoid transmission of L. infantum to sand flies.

Conclusions

We showed that dogs with ClinL are 12 times more likely to be co-infected with E. canis than clinically healthy dogs in Cyprus. These findings are of a value in the diagnosis and management of leishmaniosis in dogs. We recommend that dogs diagnosed with ClinL should be tested for E. canis co-infection using PCR. Further studies should be targeted in investigating the underlying pathology of this association.

Acknowledgements

Publication of this paper has been sponsored by Bayer Animal Health in the framework of the 13th CVBD World Forum Symposium. Authors would like to thank the veterinarians Dr Christos Yiapanis and Dr Kyriaki Neofytou from Cyvets Veterinary Centre, Paphos, Cyprus, for aiding in the collection of blood samples.

Funding

This clinical study has been sponsored by a clinical research grant from Langford Vets, University of Bristol. Part of this work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Collaborative Awards in Science and Engineering studentship (BB/1015655/1) in partnership with Zoetis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- ClinL

clinical leishmaniosis

- CMhp

“Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum”

- Ct

threshold cycle

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EU

ELISA units

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- MCH

major histocompatibility complex

- OR

odds ratio

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SEM

structural equation modelling

- VBP

vector-borne pathogen

Authors’ contributions

CA, LSG, KP, CH and ST conceived the study and all participated in its design and coordinated the experiments. CA, LSG and FS designed and performed the collection of the samples. FS extracted the DNA and performed ELISA analysis. CA and DM performed the PCR analysis. Statistical analysis was performed by CA, and SC performed the SEM. CA and ST wrote the manuscript with input from all of the authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was ethically approved by the University of Bristol’s Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Board (Veterinary Investigation number: 15/022) as well as the Royal Veterinary Collage’s Ethics and Welfare Committee (Veterinary Investigation number: 20141292). All procedures were performed in accordance with Cypriot legislation [The Dogs LAW, N. 184 (I)/2002] following written and informed consent being obtained from all dog owners.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DM, ST, KP and CH work for the Diagnostic Laboratories, Langford Vets, University of Bristol. The Laboratories provide a range of commercial diagnostic services including PCR and qPCR testing for VBPs and ELISA testing for Leishmania spp. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Charalampos Attipa, Email: attipacy@gmail.com.

Laia Solano-Gallego, Email: laia.solano@uab.cat.

Kostas Papasouliotis, Email: Kos.Papasouliotis@bristol.ac.uk.

Francesca Soutter, Email: fsoutter@rvc.ac.uk.

David Morris, Email: david.morris@bristol.ac.uk.

Chris Helps, Email: c.r.helps@bristol.ac.uk.

Scott Carver, Email: scott.carver@utas.edu.au.

Séverine Tasker, Email: s.tasker@bristol.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Killick-Kendrick R. The biology and control of phlebotomine sand flies. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17(3):279–289. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(99)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno J, Alvar J. Canine leishmaniasis: epidemiological risk and the experimental model. Trends Parasitol. 2002;18(9):399–405. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F. The prevention of canine leishmaniasis and its impact on public health. Trends Parasitol. 2013;29(7):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasker S. Exotic diseases - a growing concern? J Small Anim Pract. 2013;54(8):393–394. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vrhovec MG, Pantchev N, Failing K, Bauer C, Travers-Martin N, Zahner H. Retrospective analysis of canine vector-borne diseases (CVBD) in Germany with emphasis on the endemicity and risk factors of leishmaniosis. Parasitol Res. 2017;116(Suppl. 1):131–144. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maia C, Cardoso L. Spread of Leishmania infantum in Europe with dog travelling. Vet Parasitol. 2015;213(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Tommasi AS, Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Capelli G, Breitschwerdt EB, de Caprariis D. Are vector-borne pathogen co-infections complicating the clinical presentation in dogs? Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:97. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otranto D, Dantas-Torres F, Breitschwerdt EB. Managing canine vector-borne diseases of zoonotic concern: part one. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25(4):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Day MJ. The immunopathology of canine vector-borne diseases. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:48. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabar M-D, Francino O, Altet L, Sánchez A, Ferrer L, Roura X. PCR survey of vector-borne pathogens in dogs living in and around Barcelona, an area endemic for leishmaniosis. Vet Rec. 2009;164(4):112–6. doi: 10.1136/vr.164.4.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grigg MJ, Cox J, William T, Jelip J, Fornace KM, Brock PM, et al. Individual-level factors associated with the risk of acquiring human Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Malaysia: a case-control study. Lancet Planet Health. 2017;1(3):e97–e104. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carver S, Beatty JA, Troyer RM, Harris RL, Stutzman-Rodriguez K, Barrs VR, et al. Closing the gap on causal processes of infection risk from cross-sectional data: structural equation models to understand infection and co-infection. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:658. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1274-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazeris A, Soteriadou K, Dedet JP, Haralambous C, Tsatsaris A, Moschandreas J, et al. Leishmaniases and the Cyprus paradox. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;8(3):441–448. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attipa C, Hicks CA, Barker EN, Christodoulou V, Neofytou K, Mylonakis ME, et al. Canine tick-borne pathogens in Cyprus and a unique canine case of multiple co-infections. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8(3):341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solano-Gallego L, Miro G, Koutinas A, Cardoso L, Pennisi MG, Ferrer L, et al. LeishVet guidelines for the practical management of canine leishmaniosis. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:86. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw SE, Langton DA, Hillman TJ. Canine leishmaniosis in the United Kingdom: a zoonotic disease waiting for a vector? Vet Parasitol. 2009;163(4):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies S, Abdullah S, Helps C, Tasker S, Newbury H, Wall R. Prevalence of ticks and tick-borne pathogens: Babesia and Borrelia species in ticks infesting cats of great Britain. Vet Parasitol. 2017;244:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barker EN, Tasker S, Day MJ, Warman SM, Woolley K, Birtles R, et al. Development and use of real-time PCR to detect and quantify Mycoplasma haemocanis and “Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum” in dogs. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:167–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Parola P, Roux V, Camicas J-L, Baradji I, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Detection of ehrlichiae in African ticks by polymerase chain reaction. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94(6):707–8. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(00)90243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attipa C, Papasouliotis K, Solano-Gallego L, Baneth G, Nachum-Biala Y, Sarvani E, et al. Prevalence study and risk factor analysis of selected bacterial, protozoal and viral, including vector-borne, pathogens in cats from Cyprus. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:130. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2063-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solano-Gallego L, Villanueva-Saz S, Carbonell M, Trotta M, Furlanello T, Natale A. Serological diagnosis of canine leishmaniosis: comparison of three commercial ELISA tests (Leiscan®, ID screen® and Leishmania 96®), a rapid test (speed Leish K®) and an in-house IFAT. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):111. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chochlakis D, Ioannou I, Sandalakis V, Dimitriou T, Kassinis N, Papadopoulos B, et al. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks in Cyprus. Microb Ecol. 2012;63(2):314–23. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9926-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Gal J, Michel J-F, Rinaldi VE, Spiri D, Moretti R, Bettati D, et al. Association between functional gastrointestinal disorders and migraine in children and adolescents: a case-control study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):114–121. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouzouraa T, Rene-Martellet M, Chene J, Attipa C, Lebert I, Chalvet-Monfray K, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of canine Anaplasma platys infection in 32 naturally infected dogs in the Mediterranean basin. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7(6):1256–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. third. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mekuzas Y, Gradoni L, Oliva G, Foglia Manzillo V, Baneth G. Ehrlichia canis and Leishmania infantum co-infection: a 3-year longitudinal study in naturally exposed dogs. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(Suppl. 2):30–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cardinot CB, Silva JE, Yamatogi RS, Nunes CM, Biondo AW, Vieira RF, et al. Detection of Ehrlichia canis, Babesia vogeli, and Toxoplasma gondii DNA in the brain of dogs naturally infected with Leishmania infantum. J Parasitol. 2016;102(2):275–279. doi: 10.1645/15-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortese L, Pelagalli A, Piantedosi D, Mastellone V, Manco A, Lombardi P, et al. Platelet aggregation and haemostatic response in dogs naturally co-infected by Leishmania infantum and Ehrlichia canis. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2006;53(10):546–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2006.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortese L, Pelagalli A, Piantedosi D, Cestaro A, Di Loria A, Lombardi P, et al. Effects of therapy on haemostasis in dogs infected with Leishmania infantum, Ehrlichia canis, or both combined. Vet Rec. 2009;164(14):433–434. doi: 10.1136/vr.164.14.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baneth G, Koutinas AF, Solano-Gallego L, Bourdeau P, Ferrer L. Canine leishmaniosis - new concepts and insights on an expanding zoonosis: part one. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24(7):324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alves CF, de Amorim IF, Moura EP, Ribeiro RR, Alves CF, Michalick MS, et al. Expression of IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, IL-10 and TGF-beta in lymph nodes associates with parasite load and clinical form of disease in dogs naturally infected with Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;128(4):349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barbieri CL. Immunology of canine leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28(7):329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franca-Costa J, Van Weyenbergh J, Boaventura VS, Luz NF, Malta-Santos H, Oliveira MC, et al. Arginase I, polyamine, and prostaglandin E2 pathways suppress the inflammatory response and contribute to diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(3):426–435. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saha A, Biswas A, Srivastav S, Mukherjee M, Das PK, Ukil A. Prostaglandin E2 negatively regulates the production of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and IL-17 in visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2014;193(5):2330–2339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrus S, Waner T, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Fishman Z, Bark H, Harmelin A. Down-regulation of MHC class II receptors of DH82 cells, following infection with Ehrlichia canis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003;96(3–4):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinnell RJ, Kennedy LJ, Barnes A, Courtenay O, Dye C, Garcez LM, et al. Susceptibility to visceral leishmaniasis in the domestic dog is associated with MHC class II polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 2003;55(1):23–28. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alvar J, Aparicio P, Aseffa A, Den Boer M, Canavate C, Dedet JP, et al. The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):334–359. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00061-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davidson RN. Practical guide for the treatment of leishmaniasis. Drugs. 1998;56(6):1009–1018. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pintado V, Martin-Rabadan P, Rivera ML, Moreno S, Bouza E. Visceral leishmaniasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected patients: a comparative study. Medicine. 2001;80(1):54–73. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olivier M, Badaro R, Medrano FJ, Moreno J. The pathogenesis of Leishmania/HIV co-infection: cellular and immunological mechanisms. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97(Suppl. 1):79–98. doi: 10.1179/000349803225002561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katherine K, Suzanne MC. The role of monocytes and macrophages in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9(21):1893–1903. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ehrlichiosis CLA. Related infections. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33(4):863–884. doi: 10.1016/S0195-5616(03)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baneth G, Samish M, Shkap V. Life cycle of Hepatozoon canis (Apicomplexa: Adeleorina: Hepatozoidae) in the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus and domestic dog (Canis familiaris) J Parasitol. 2007;93(2):283–299. doi: 10.1645/GE-494R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pryor WH, Jr, Bradbury RP. Haemobartonella canis infection in research dogs. Lab Anim Sci. 1975;25(5):566–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sainz A, Roura X, Miro G, Estrada-Pena A, Kohn B, Harrus S, et al. Guideline for veterinary practitioners on canine ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis in Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:75. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seneviratna P, Weerasinghe, Ariyadasa S. Transmission of Haemobartonella canis by the dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Res Vet Sci. 1973;14(1):112–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novacco M, Meli ML, Gentilini F, Marsilio F, Ceci C, Pennisi MG, et al. Prevalence and geographical distribution of canine hemotropic mycoplasma infections in Mediterranean countries and analysis of risk factors for infection. Vet Microbiol. 2010;142(3–4):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrus S, Kenny M, Miara L, Aizenberg I, Waner T, Shaw S. Comparison of simultaneous splenic sample PCR with blood sample PCR for diagnosis and treatment of experimental Ehrlichia canis infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(11):4488–4490. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4488-4490.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusion of this article are included within the article.