Abstract

Background

Multimorbidity, the presence of two or more non-communicable diseases (NCD), is a costly and complex challenge for health systems globally. Patients with NCDs incur high levels of out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE), often on medicines, but the literature on the association between OOPE on medicines and multimorbidity has not been examined systematically.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted via searching medical and economics databases including Ovid Medline, EMBASE, EconLit, Cochrane Library and the WHO Global Health Library from year 2000 to 2016. Study quality was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. PROSPERO: CRD42016053538.

Findings

14 articles met inclusion criteria. Findings indicated that multimorbidity was associated with higher OOPE on medicines. When number of NCDs increased from 0 to 1, 2 and ≥3, annual OOPE on medicines increased by an average of 2.7 times, 5.2 times and 10.1 times, respectively. When number of NCDs increased from 0 to 1, 2, ≥2 and ≥3, individuals spent a median of 0.36% (IQR 0.15%–0.51%), 1.15% (IQR 0.62%–1.64%), 1.41% (IQR 0.86%–2.15%), 2.42% (IQR 2.05%–2.64%) and 2.63% (IQR 1.56%–4.13%) of mean annual household net adjusted disposable income per capita, respectively, on annual OOPE on medicines. More multimorbidities were associated with higher OOPE on medicines as a proportion of total healthcare expenditures by patients. Some evidence suggested that the elderly and low-income groups were most vulnerable to higher OOPE on medicines. With the same number of NCDs, certain combinations of NCDs yielded higher medicine OOPE. Non-adherence to medicines was a coping strategy for OOPE on medicines.

Conclusion

Multimorbidity of NCDs is increasingly costly to healthcare systems and OOPE on medicines can severely compromise financial protection and universal health coverage. It is crucial to recognise the need for better equity and financial protection, and policymakers should consider health system financial options, cost sharing policies and service patterns for those with NCD multimorbidities.

Keywords: public health

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Patients with multimorbidity are disproportionately financially burdened due to complex health needs and high healthcare utilisation.

Medicines constitute the largest proportion of out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) for patients with multimorbidity.

Current health systems fail to provide sufficient financial protection for OOPE on medicines.

What are the new findings?

There was an association between level of multimorbidity in patients and out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) on medicines. More multimorbidities were associated with higher OOPE on medicines as a proportion of total healthcare expenditures by patients.

Even with the same number of non-communicable diseases (NCD), certain specific combinations of chronic conditions yielded higher OOPE on medicines.

The elderly were more vulnerable to higher OOPE on medicines, while some evidence suggested medicine OOPE accounted for a greater proportion of income for low-income groups.

In patients with multimorbidity, non-adherence was a coping strategy for OOPE on medicines, with adverse health consequences.

Recommendations for policy.

It is crucial to recognise the need for better equity and financial protection, and policymakers should consider health system financial options, cost sharing policies and service patterns for those with NCD multimorbidities.

Policymakers should move from a single-disease framework to one that takes into account multimorbidity, when allocating funds and when designing policies aimed at financial protection.

Targeted government funding and support programmes should take into account multimorbidity status of individuals, particularly for the elderly and low-income groups who are most vulnerable to OOP hardships.

Policy measures could include exemptions from certain costs for the elderly and low socioeconomic status groups, lower caps on copayments and subsidies for vital drugs.

Prescription drug cost sharing benefit plans must be designed to provide enhanced and broadened coverage for multimorbidities, particularly for certain NCD combinations.

A crucial clinical implication relates to the need for better clinical prescription guidelines to prevent prescription of unessential medicines and generic drugs for chronic illness which may cause unwarranted expenditures on medicines by patients.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally.1 The United Nations and the World Health Organization(WHO) have established coordinated responses to address NCDs worldwide.2 3 A particular challenge with NCDs is multimorbidity, the presence of two or more NCDs.4 Patients with multimorbidity are disproportionately burdened with illness, and economically, due to complex needs and high healthcare utilisation.5 A study of six low-middle income countries (LMIC) found that the highest contribution to out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) in patients with multimorbidity was on medicine.6 Using nationally representative data, a study in the USA found that elderly patients with three or more NCDs used five or more prescription drugs, revealing that medicines contributed to high healthcare expenditure by patients.7

Given the scale of the healthcare and financial burden of NCDs, understanding the financial burden on patients with multimorbidity, particularly on medicines, is crucial when developing strategies towards universal health coverage (UHC), which aims to provide access to health services, including medicines, without financial hardship, and in order to ensure equity in financial protection.8 A review on the global impact on NCDs on impoverishment revealed that OOP medical expenditures drive households into financial catastrophe and impoverishments.5 In many LMICs, health systems fail to protect individuals from OOPE on medicines due to inequitable financing, where insurance schemes or benefits packages do not cover all essential medicines, or patients have to incur substantial copayments.6 9 A study in rural India found medicines accounted for 49% of total aggregate OOPE for illnesses.10 Patients in developed countries also incur large OOPE for medicines. A 2003 survey of Medicare beneficiaries in the USA aged above 65 years showed that more than one-quarter had no prescription coverage, and almost half of low-income seniors in selected states lacked coverage for medicines.7 Inadequate insurance that covers inpatient and outpatient services but not costs of medicines is likely to worsen access to medicines.11

This review contributes to the existing literature by investigating evidence on the relationship between multimorbidities and OOPE on medicines. To date, existing reviews have only examined the overall economic burden of NCDs in countries, but not OOPE incurred by individuals.5 12 13 Other studies have investigated total OOPE on healthcare overall, but not on medicines alone specifically.14 15 To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a systematic review of published studies and synthesised current literature on OOPE on medicines by patients with NCD multimorbidities.

Methodology

We followed the methods detailed in a peer-reviewed systematic review protocol that is registered with PROSPERO (registration CRD 42016053538). We systematically searched electronic databases (Ovid Medline, Cochrane Library, EconLIT, EMBASE, WHO Global Health Library) in January 2017 for articles published from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2016. We only included studies from year 2000 onwards to concentrate on recent relevant studies. Bibliographies of included articles were searched for additional articles that met inclusion criteria.

Search strategy involved keywords and Medical Subject Headings. Search strategies were tailored to each database. Online supplementary appendix pp 1–4 describes detailed search strategies for each database. In summary, keywords used for identifying NCD multimorbidity included ‘Chronic disease’, ‘Chronic condition’, ‘Chronic illness’, ‘Multimorbid’, ‘Multimorbidity’ and ‘Non-communicable’; keywords for identifying medicines were ‘Prescription drug’, ‘Medicine’, ‘Drug’, ‘Pharmaceutical’ and ‘Polypharmacy’; and keywords for identifying outcome measure of OOPE were ‘Out-of-pocket’, ‘Financial’, ‘Utilisation’, ‘Health expenditures’, ‘Health care cost’ and ‘Drug cost’.

bmjgh-2017-000505supp001.pdf (477.8KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 1 shows our detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for reviewed studies

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Study design | |

| We included articles from the year 2000 to 31 Dec 2016, without any restriction on study design. We only included original primary studies published in peer-reviewed journals. Only studies in English were included. | We excluded reviews, commentaries, letters, issue briefs, editorials, poster presentations, or conference papers. |

| Populations and settings | |

| We included articles without any restriction on populations and settings (ie, included low-middle income countries, developed countries, any age groups, etc). | NA |

| Intervention | |

| Subjects with non-communicable disease (NCD) multimorbidity. | Subjects with single chronic diseases and/or infectious diseases. |

| Comparator | |

| Not applicable in this review. | |

| Outcome: OOPE on medicines for multimorbidity | |

| 1. First, we ensured the type of expenditure studied in the article was OOPE borne by patients. We defined OOPE as spending that was not reimbursed, but directly incurred by the patient from their income, as a proportion of household expenditures, or from cost sharing from insurance. OOPE did not include expenditure on insurance premiums. | 1. Articles not on OOPE were excluded: for example, articles on national healthcare spending, or expenditure by insurance companies, instead of OOPE by individuals. |

| 2. Second, we ensured OOPE was for medicines. Medicines could be for treatment of chronic conditions, including prescription drugs, non-prescription drugs, medications, pharmaceuticals, alternative medicines, and complementary medicines. | 2. Articles that only studied total inpatient costs, or total outpatient costs, even though it incorporated costs of medicines, were excluded. |

| 3. Thirdly, we ensured OOPE on medicines was compared for different numbers of multimorbidities. Articles must specify OOPE on medicines for different numbers of NCDs, or different combinations of NCDs that consisted of different numbers of NCDs. For example, article compares OOPE on medicines for 0, 1, 2–3, 4–6 NCDs, or article compares OOPE on medicines for diabetes (ie, 1 NCD) and diabetes with arthritis and depression (ie, 3 NCDs). | 3. OOPE on medicines not studied in association with specific numbers of NCDs. For example, OOPE was studied in associated with Charlson-comorbidity Index instead of number of NCDs. |

OOPE, out-of-pocket expenditure.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers reviewed titles and abstracts. Subsequently, article full texts were screened for eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Information extracted from articles included reference information, population and study settings, study design and data sources, key findings on relationship between OOPE for medicines and multimorbidity, and other secondary outcomes including medicine utilisation for multimorbidity, coping strategies for OOPE on medicines and OOPE for other healthcare services.

Currency of OOPE

For comparability, all OOPE on medicines was converted to 2015 US$. This was done by using Purchasing Power Parity Indices to convert costs from one country to another (in this case, the USA), and subsequently the overall US Consumer Price Index (CPI) was used to convert historical costs to 2015 US$.16 17 If the year of OOPE was not specified in the article, we calculated OOPE based on the year of data collection (eg, survey year). OOPE was reported to the nearest dollar.

Calculations of OOPE as a proportion of mean annual national average wages

All selected articles had results on OOPE on medicines, but a few did not clearly specify absolute amounts (eg, OOPE reported as percentage of income). Hence, we contacted authors of the latter subset of articles. As a result, we had absolute amounts of OOPE on medicines (for different numbers of multimorbidities) for 11 of our 14 included studies. One of these 11 of 14 studies reported absolute OOPE on medicines for last outpatient visit, and the remaining 10 of 14 studies reported absolute annual OOPE on medicines.

We obtained annual national average wages (2015) (calculated by OECD: average wages are obtained by dividing the national-accounts-based total wage bill by the average number of employees in the total economy, which is then multiplied by the ratio of the average usual weekly hours per full-time employee to the average usual weekly hours for all employees) from the OECD,18 and mean annual household net disposable income per capita from OECD.19 Subsequently, using the 10 studies that reported annual OOPE on medicines, we calculated OOPE on medicines as a proportion of annual national average wages, and OOPE on medicines as a proportion of mean annual household net adjusted disposable income per capita, to allow comparability between settings and years.

Quality evaluation

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) is a well-established quality assessment tool for observational studies,20 21 which we used to evaluate the quality of studies included in this review. We modified the tool to suit our specific purposes by designing questions directly addressing OOPE and NCDs (online supplementary appendix pp 5–6). We assessed quality of articles in three categories—population selection, comparability and outcome measures. Under population selection, we assessed if population studied was nationally representative, how NCDs were measured (eg, self-reported) and how multimorbidities were classified (eg, 0 NCD, 1 NCD, 2–3 NCDs, 4–6 NCDs). For comparability, we assessed if studies might have incurred bias as a result of study design and analysis. For outcome measures, we assessed if measurement of OOPE for medicines was reliable (eg, self-reported or verified with administrative data).

We measured six items in the NOS quality assessment tool: four items for population selection, one item for comparability, one item for outcome. A maximum of 1 point can be awarded for each item. The NOS scale can have a maximum of 6 points total. A score was computed by adding the number of points. Studies were categorised into high (4–6 points), moderate (3 points) and satisfactory (0–2 points) quality.

Statistical methods

Due to considerable heterogeneity of studies for OOPE on medicines, meta-analysis of OOPE on medicines was precluded. We discussed our findings narratively and presented median and IQR of absolute OOPE on medicines calculated from our included studies, stratified by number of NCDs.

In addition, for each study that provided absolute mean annual OOPE on medicines for different numbers of NCDs, we calculated the ratios of absolute mean annual OOPE on medicines across groups with different numbers of NCDs, relative to the group with the fewest NCDs, for comparability within studies. For example, for an article that reported absolute mean annual OOPE for 0 NCD, 1–2 NCDs and ≥3 NCDs, we calculated the ratio of absolute mean annual OOPE on medicines for ≥3 NCDs to absolute mean OOPE on medicines to 0 NCD, as well as the ratio of absolute mean annual OOPE on medicines for 1–2 NCDs to absolute mean annual OOPE on medicines for 0 NCD.

Results

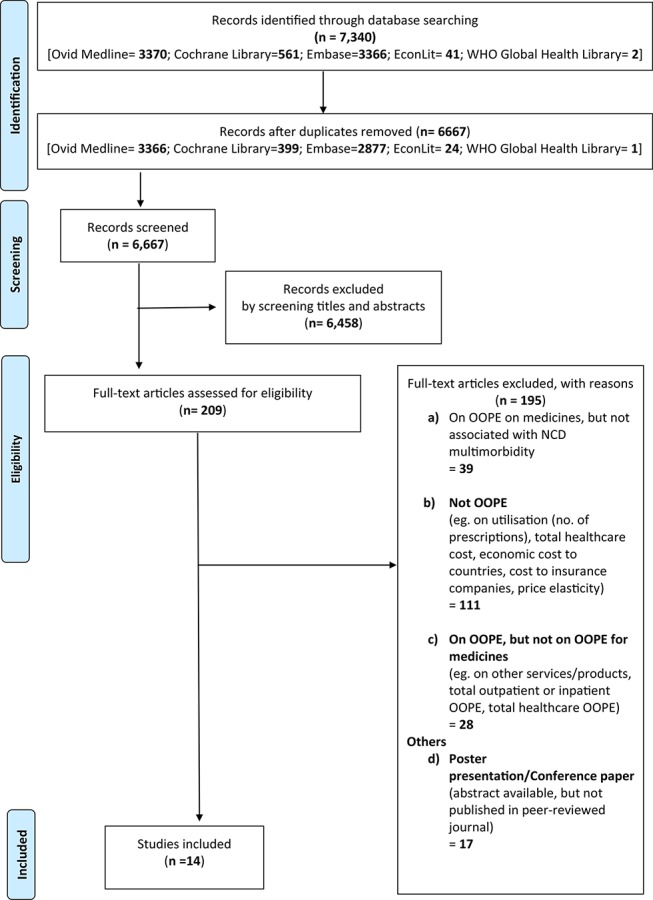

A total of 7340 records were identified from database searches. After removing duplicates, there were 6667 records, which were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 209 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart. Fourteen primary articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review.22–35

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart. NCD, non-communicable disease; OOPE, out-of-pocket expenditure.

Characteristics of included articles

Characteristics of the 14 selected studies are summarised in table 2.22–35 Eight of 14 articles were published between 2011 and 2016, three between 2006 and 2010, and three between 2000 and 2005. Six studies were conducted in the USA, two in Canada, one in Australia, four in South Korea and one in India. All articles were observational. Three articles studied populations of all ages, four studied elderly populations ≥65 years and seven studied those aged between 18 and 64 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of selected articles (n=14)

| No. of papers | n=6 | n=2 | n=1 | n=4 | n=1 | n=14 |

| Characteristic | USA | Canada | Australia | Korea | India | Total |

| Publication year | ||||||

| 2000–2005 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| 2006–2010 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 2011–2013 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2014–2016 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | |

| Population age (years) | ||||||

| ≥65 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| 15–64 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| All | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Study design | ||||||

| Cross-sectional | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 13 |

| Pooled cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | ||||

| How multimorbidity was studied | ||||||

| By number of NCDs | 6 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 13 | |

| Specific combinations of NCDs | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Secondary outcomes for multimorbidity | ||||||

| (a) Impact of multimorbidity on medicine utilisation | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||

| No | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| (b) Coping strategies for OOPE for Medicines | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | 2 | ||||

| No | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 12 | |

| c) OOPE for other healthcare services | ||||||

| Yes | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||

| No | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | |

| Quality assessment | ||||||

| High | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Moderate | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Satisfactory | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

NCD, non-communicable disease; OOPE, out-of-pocket expenditure.

Thirteen of 14 articles studied multimorbidity based on number of NCDs, while the remaining one article studied specific combinations of NCDs. In general, articles studied OOPE on medicines for zero, one, two and three or more NCDs. The majority (11 of 14 papers) of studies referred to NCDs as ‘chronic conditions’ or ‘medical conditions’. Two studies defined NCDs as conditions that had lasted, or were expected to last, 12 or more months and resulted in functional limitations, and/or a need for ongoing medical care. One study defined them as chronic conditions that lasted or expected to last 3 or more months. Four of 14 articles did not specify the list of NCDs studied; for the remaining 10 papers, five papers included a full list of self-reported NCDs that were studied, while five papers stated the most prevalent self-reported NCDs. The most common NCDs studied were diabetes, hypertension, stroke, arthritis and respiratory disease.

Quality of included articles

Online supplementary appendix p 7 shows the scoring for quality assessment, where studies were categorised into high (4–6 points), moderate (3 points) or satisfactory (0–2 points) quality. Median and mean quality scores for eligible studies were 3.5 and 3.4, respectively, with 50% of articles categorised as high quality. All papers, except the three papers classified as satisfactory quality, were nationally representative. Eleven of 14 papers (80%) only measured NCDs with self-reporting. Six of 14 papers did not compare results with a reference group without NCDs (ie, they examined OOPE for different numbers of multimorbidities (eg, 2 NCDs, 3–5 NCDs, and so on) but did not compare with patients with 0 NCD).

Out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines

Table 3 summarises key results on OOPE on medicines by numbers of multimorbidities.

Table 3.

Primary outcomes

| Ref | Study design, data, population, settings |

Primary outcomes | Quality assessment |

||

| Annual absolute amounts of OOPE on medicines (Ratios of OOPE) |

OOPE on medicines as a proportion of (i) Annual national average wages (ii) Mean annual household net adjusted disposable income per capita | OOPE on medicines as a proportion of total healthcare/medical services expenditure | |||

| Crystal et al

22

USA |

Cross-sectional. Data: 1995 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). No. of subjects: 7886 Age:≥65 |

0 NCDs: $103 (reference) 1 NCD: $254 (2.5) 2 NCDs: $379 (3.7) 3–5 NCDs: $581 (5.6) >5 NCDs: $791 (7.7) |

(i)

0 NCDs: 0.18% 1 NCD: 0.43% 2 NCDs: 0.65% 3–5 NCDs: 0.99% >5 NCDs: 1.35% (ii) 0 NCDs: 0.25% 1 NCD: 0.62% 2 NCDs: 0.92% 3–5 NCDs: 1.41% >5 NCDs: 1.93% |

0 NCDs: 17.1% 1 NCD: 27.3% 2 NCDs: 33.2% 3–5 NCDs: 36.6% >5 NCDs: 35.6% |

High |

| Hwang et al

23

USA |

Cross-sectional. Data: 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). No. of subjects: 22 326 individuals and 8605 families. Age: All |

Aged<65

0 NCDs: $62 (reference) 1 NCD: $166 (2.7) 2 NCDs: $345 (5.6) ≥3 NCDs: $669 (10.8) Aged≥65 0 NCDs: $171 (reference) 1 NCD: $354 (2.1) 2 NCDs: $661 (3.9) ≥3 NCDs: $1006 (5.9) |

(i)

Aged<65 0 NCDs: 0.12% 1 NCD: 0.28% 2 NCDs: 0.59% ≥3 NCDs: 1.14% Aged≥65 0 NCDs: 0.29% 1 NCD: 0.60% 2 NCDs: 1.13% ≥3 NCDs: 1.71% (ii) Aged<65 0 NCDs: 0.15% 1 NCD: 0.40% 2 NCDs: 0.84% ≥3 NCDs: 1.63% Aged≥65 0 NCDs: 0.42% 1 NCD: 0.86% 2 NCDs: 1.61% ≥3 NCDs: 2.45% |

Aged<65

0 NCDs: 17.1% 1 NCD: 27.0%, 2 NCDs: 33.8% ≥3 NCDs: 46.3% Aged≥65 0 NCDs: 24.9%, 1 NCD: 39.4%, 2 NCDs: 50.6% ≥3 NCDs: 50.5% |

High |

| Sambamoorthi et al

24

USA |

Cross-sectional. Data: Medicare beneficiaries from 1997 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Cost and Use files. No. of subjects: 8, 814 individuals. Age:≥65 |

0 NCDs: $147 (reference) 1 NCD: $284 (1.9) 2–3 NCDs: $516 (3.5) 4–6 NCDs: $833 (5.7) >6 NCDs: $1316 (9.0) |

(i)

0 NCDs: 0.25% 1 NCD: 0.48% 2–3 NCDs: 0.88% 4–6 NCDs: 1.42% >6 NCDs: 2.24% (ii) 0 NCDs: 0.36% 1 NCD: 0.69% 2–3 NCDs: 1.26% 4–6 NCDs: 2.03% >6 NCDs: 3.20% |

NIL | High |

| Gellad et al

25

USA |

Cross-sectional. Data: 1996–2000 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC). No. of subjects: 5996 individuals Age:≥65 |

0 NCDs: $407 (reference) 1 NCD: $898 (2.2) 2 NCDs: $1377 (3.4) ≥3 NCDs: $2083 (5.1) |

(i)

0 NCDs: 0.69% 1 NCD: 1.53% 2 NCDs: 2.34% ≥3 NCDs: 3.55% (ii) 0 NCDs: 0.99% 1 NCD: 2.19% 2 NCDs: 3.35% ≥3 NCDs: 5.07% |

NIL | Moderate |

| Ruger et al

26

Korea |

Cross-sectional. Data: 1998 Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (KHNS). No. of subjects: 13 523 households and 39 060 household members. Age: All |

OOPE on medicines burden ratio

(Income quintile 0%–20%) 0 NCDs: 6 1 NCD: 22.6 2 NCDs: 27.4 ≥3 NCDs: 37.7 OOPE on medicines burden ratio (Income quintile 80%–100%) 0 NCDs: 1.4 1 NCD: 3.3 2 NCDs: 4.9 ≥3 NCDs: 3.9 |

NIL | NIL | High |

| Paez et al

27

USA |

Pooled cross-sectional Cross-sectional Data: 2005 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Longitudinal Data: 1996 and 2005 MEPS. No. of subjects: Unspecified, weighted to represent 292 million civilian non-institutionalised US population. Age: All. |

Aged<65

0 NCDs: $54 (reference) 1 NCD: $255 (4.7) 2 NCDs: $557 (10.3) ≥3 NCDs: $1153 (21.4) Aged≥65 0 NCDs: $210 (reference) 1 NCD: $547 (2.6) 2 NCDs: $958 (4.6) ≥3 NCDs: $1566 (7.4) |

(i)

Aged<65 0 NCDs: 0.092% 1 NCD: 0.43% 2 NCDs: 0.95% ≥3 NCDs: 2.0% Aged≥65 0 NCDs: 0.36% 1 NCD: 0.93% 2 NCDs: 1.63% ≥3 NCDs: 2.67% (ii) Aged<65 0 NCDs: 0.13% 1 NCD: 0.62% 2 NCDs: 1.36% ≥3 NCDs: 2.81% Aged≥65 0 NCDs: 0.51% 1 NCD: 1.33% 2 NCDs: 2.33% ≥3 NCDs: 3.81% |

Aged<65

0 NCDs: 13.8% 1 NCD: 34.8% 2 NCDs: 48.3% ≥3 NCDs: 59.5% Aged≥65 0 NCDs: 31.5% 1 NCD: 50.5% 2 NCDs: 63.5% ≥3 NCDs: 63.0% |

High |

| Kemp et al

28

Australia |

Cross-sectional. Data: 2 Australian Bureau of Statistics' (ABS) surveys: the Household Expenditure Survey and Survey of Income and Expenditure 2009–2010. No. of subjects: 9774 households and 17 995 individuals. Age:≥15 |

1 NCD: Diabetes = $513 (reference) 3 NCDs: Diabetes+gastro-oesophageal reflux disease+depression = $1536 (3.0) 1 NCD: Acute coronary syndrome = $2290 (reference) 3 NCDs: Acute coronary syndrome+asthma + osteoarthritis =$3151 (1.4) |

(i)

1 NCD: Diabetes =1.02% 3 NCDs: Diabetes+gastro-oesophageal reflux disease+depression =3.06% 1 NCD: Acute coronary syndrome =4.57% 3 NCDs: Acute coronary syndrome+asthma + osteoarthritis =6.28% (ii)1 NCD: Diabetes=1.55% 3 NCDs: Diabetes+gastro-oesophageal reflux disease+depression =4.64% 1 NCD: Acute coronary syndrome =6.91% 3 NCDs: Acute coronary syndrome+asthma + osteoarthritis =9.51% |

NIL | Satisfactory |

| Campbell et al

29

Canada |

Cross-sectional. Data: Survey designed by the interdisciplinary Chronic Disease Collaboration- Barriers to Care for People with Chronic Health Conditions (BCPCHC), Feb 1-March 31, 2012. No. of subjects: 1849 individuals. Age:≥40 |

Aged<65

1 NCD: $418 (reference) ≥2 NCDs: $624 (1.5) Aged≥65 1 NCD: $549 (reference) ≥2 NCDs: $806 (1.5) |

(i)

Aged<65 1 NCD: 0.87% ≥2 NCDs: 1.30% Aged≥65 1 NCD: 1.15% ≥2 NCDs: 1.68% (ii) Aged<65 1 NCD: 1.37% ≥2 NCDs: 2.05% Aged≥65 1 NCD: 1.80% ≥2 NCDs: 2.64% |

NIL | Satisfactory |

| Park et al

30

Korea |

Cross-sectional. Data: 2008 Korea Health Panel Survey (KHPS). No. of subjects: 2342 individuals. Age:≥65 |

OOPE on medicines cost ratio

0 NCDs: 1.00 1 NCD: 2.11 ≥2 NCDs: 4.18 |

NIL | NIL | High |

| Pati et al

31

India |

Cross-sectional. Data: WHO study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) wave 1 survey of India, 2007. Subjects: 12 198 individuals. Age:≥18 |

(Not annual OOPE, OOPE in last outpatient visit) 0 NCDs: $6 1 NCD: $7 ≥2 NCDs: $8 |

NIL | 0 NCDs: 73.55% 1 NCD: 66.23% ≥2 NCDs: 61.05% |

High |

| Park et al

32

Korea |

Cross-sectional (from three waves) Data: 2008 first-wave survey, 2008 second-wave survey, 2009 third-wave survey from Korea Health Panel Survey. No. of subjects: 5640 individuals Age:≥20 |

OOPE on medicines OR for financial burden

1 NCD: 1.00 2 NCDs: 3.49 ≥3 NCDs: 8.61 |

NIL | NIL | Moderate |

| Thorpe et al

33

USA |

Cross-sectional. Data: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) 2012, and Health Insurance Exchange Compare dataset 2014. No. of subjects: Unspecified Age: 18–64 years |

1 NCD: $396 (reference) 2 NCDs: $595 (1.5) 3 NCDs: $795 (2.0) ≥4 NCDs: $1145 (2.9) |

(i)

1 NCD: 0.67% 2 NCDs: 1.01% 3 NCDs: 1.35% ≥4 NCDs: 1.95% (ii) 1 NCD: 0.96% 2 NCDs: 1.45% 3 NCDs: 1.94% ≥4 NCDs: 2.79% |

NIL | Moderate |

| Hennessy et al

34

Canada |

Cross-sectional. Data: Survey designed by the interdisciplinary chronic disease Collaboration- Barriers to Care for People with Chronic Health Conditions (BCPCHC), Feb 1-March 31, 2012. No. of subjects: 1849 individuals Age:≥40 |

1 NCD: $474 (reference) ≥2 NCDs: $736 (1.6) |

(i)

1 NCD: 1.00% ≥2 NCDs: 1.54% (ii) 1 NCD: 1.56% ≥2 NCDs: 2.42% |

NIL | Satisfactory |

| Jung et al

35

Korea |

Cross-sectional. Data: 2008 Korea Health Panel Survey (KHPS). No. of subjects: 8103 individuals. Age:≥20 |

1 NCD: $82 (reference) 2 NCDs: $156 (1.9) ≥3 NCDs: $260 (3.2) |

(i)

1 NCD: 0.25% 2 NCDs: 0.45% ≥3 NCDs: 0.79% (ii) 1 NCD: 0.42% 2 NCDs: 0.81% ≥3 NCDs: 1.34% |

Moderate | |

NCD, non-communicable disease; OOPE, out-of-pocket expenditure.

Absolute OOPE on medicines

Ten of 14 articles provided absolute amounts of annual OOPE on medicines. In all 10 studies, a greater number of NCDs were associated with a larger absolute annual OOPE on medicines, and hence, as a proportion of annual national average wages, and proportion of mean annual household net adjusted disposable income per capita.

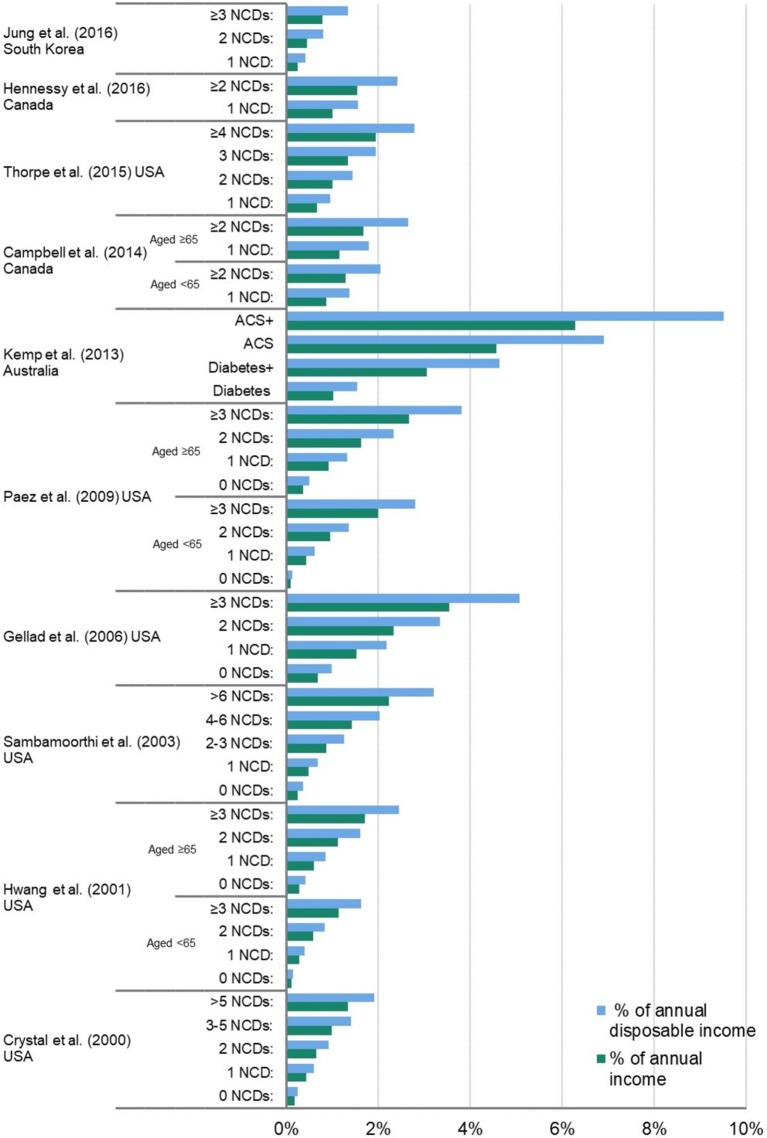

Figure 2 shows the associations between numbers of multimorbidities, and OOPE on medicines as a proportion of annual national average wages, and proportion of mean annual household net adjusted disposable income per capita.

Figure 2.

OOPE on medicines as a proportion of annual national average wages, and mean annual household net disposable income per capita, by numbers of multimorbidities, for studies with absolute annual OOPE on medicines 1Population aged <65 2 Population aged ≥65 ACS Acute Coronary Syndrome ACS+Acute Coronary Syndrome with asthma and osteoarthritis Diabetes+ Diabetes with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and depression. NCD, non-communicable disease; OOPE, out-of-pocket expenditure.

When number of NCDs increased from 0 to 1, 2 and ≥3, annual OOPE on medicines increased by an average of 2.7 times, 5.2 times and 10.1 times, respectively. When number of NCDs increased from 0 to 1, 2, ≥2 and ≥3, individuals spent a median of 0.36% (IQR 0.15%–0.51%), 1.15% (IQR 0.62%–1.64%), 1.41% (IQR 0.86%–2.15%), 2.42% (IQR 2.05%–2.64%) and 2.63% (IQR 1.56%–4.13%) of mean annual household net adjusted disposable income per capita, respectively, on annual OOPE on medicines.

The magnitude of OOPE increment as number of NCDs increased varied among studies. In Crystal et al’s study,22 a high-quality paper from the USA on a nationally representative survey on Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and above, annual OOPE on medicines was 2.5 times (US$254), 3.7 times (US$379), 5.6 times (US$581) and 7.7 times higher (US$791) for those with 1, 2, 3–5 and >5 NCDs, respectively, compared with those with no NCDs (US$103). Jung et al’s study,35 a moderate-quality paper from Korea on a nationally representative population aged 20 and above, reported that absolute amounts of annual OOPE on medicines, compared with those with 1 NCD (US$82), were 1.9 times (US$156) and 3.2 times higher (US$260) for those with 2 and ≥3 NCDs, respectively.

One study, by Kemp et al 28 from Australia, ranked in the satisfactory-quality category, which conducted a nationally representative survey of households and individuals across Australian states and territories, examined multimorbidity by specific disease clusters, in addition to examining number of NCDs. With the same number of NCDs, certain combinations of NCDs had higher OOPE on medicines than others. The article compared patients with diabetes only (one NCD) with those with three NCDs (diabetes with depression and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease), and compared patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (one NCD) with those with three NCDs (ACS with asthma and osteoarthritis). Those with ACS (either alone or in conjunction with others) experienced greater OOPE compared with patients with diabetes (either alone or in conjunction with others).

OOPE on medicines as proportion of total healthcare expenditure by patients

Four papers studied the share of OOPE on medicines in total healthcare expenditure by individuals and households. In general, patients with more multimorbidities experienced higher OOPE on medicines, as a proportion of total OOPE on healthcare and medical services by patients. Paez et al 27 studied elderly subjects aged more than 65 years in the USA and reported that annual OOPE on medicines as a proportion of total healthcare expenditures by patients increased from 31.5% (zero NCD) to 50.5%, and to 63.5%, for one and two NCDs, respectively.

Impact of age on OOPE on medicines

Three articles by Hwang et al,23 Paez et al 27 and Campbell et al 29 (two high-quality category and one satisfactory-quality category, respectively) investigated differences in OOPE on medicines among elderly and the young. All three studies consistently showed absolute annual OOPE on medicines for subjects aged older than 65 years was higher than those aged less than 65 years, at every multimorbidity level. In Hwang et al’s study23 for subjects aged less than 65 years, annual OOPE on medicines was US$62, US$166, US$345 and US$669 for zero, one, two, and three or more NCDs, respectively, whereas for those aged above 65 years, annual OOPE on medicines was higher at US$171, US$354, US$661 and US$1006 for zero, one, two, and three or more NCDs, respectively.

Increased financial burden of lower income groups

Ruger and Kim’s study,26 a paper ranked as high quality, using the Korean National Health and Nutrition survey, found that patients from lower income quintiles suffered greater OOPE burden ratios (ratio of average OOPE to individual’s share of household income). The authors reported that OOPE burden ratios for subjects of the lowest income quintile were 6.0, 22.6, 27.4 and 37.7 for patients with zero, one, two, and three or more NCDs, respectively. OOPE burden ratios for subjects from the highest income quintile experienced lower burdens of 1.4, 3.3 and 4.9 for zero, one and two NCDs, respectively, and even dropped to 3.9 for those with ≥3 NCDs.

Secondary outcomes

Online supplementary appendix pp 8–11 summarises secondary outcomes. Five papers studied the association of multimorbidity with medicine utilisation. Consumption of medicines increased with multimorbidity. In Hennessy et al’s study,34 as the proportion of household income spent on OOPE on medicines increased from 0 to 0%–5% to >5%, mean number of medications used increased from 4.0 to 3.9 to 6.9, respectively. Two papers, both ranked as satisfactory quality, studied coping strategies for OOPE on medicines. Non-adherence to medicines was the coping strategy for high OOPE incurred by patients. Campbell et al 29 found 37.7% of respondents who reported financial barriers to medications stopped taking their prescribed medications. Hennessy et al 34 found that 5.2% of individuals spending less than 5% of their income on OOPE on medicines, and 21.5% of individuals spending more than 5% of their income on OOPE on medicines, reported non-adherence.

Online supplementary appendix pp 12–13 displays which primary and secondary outcomes were reported by each of the 14 papers.

Discussion

Summary and interpretation of findings

A greater number of multimorbidities were associated with higher OOPE on medicines. This finding could be explained by polypharmacy worsening with more NCDs, which gives rise to higher OOPE on medicines. The problem of polypharmacy may be a result of single-disease guidelines applied to multimorbid patients, even though such guidelines were designed based on frameworks that excluded patients with multimorbidities.4 6 Some evidence from our results suggested that with the same number of NCDs, specific combination of NCDs yielded higher OOPE on medicines. This is likely due to certain NCDs requiring more medicines or more expensive medicines than others. A greater number of multimorbidities were also associated with higher OOPE on medicines as a proportion of total healthcare expenditures by patients, which may have implications that multimorbid patients with higher OOPE on medicines had to allocate less resources to other medical services.

We also found that absolute OOPE on medicines for the elderly was higher than the young, at every multimorbidity level, indicating that being older is associated with being more vulnerable to higher OOPE on medicines, consistent with other studies showing that the elderly tend to suffer from higher medicine utilisation and healthcare expenditures.36 Some evidence from our study also suggested that OOPE on medicines accounted for a substantially greater proportion of income for low-income groups. Our results are consistent with findings from other systematic reviews on high susceptibility of household impoverishment from poor management of NCDs in low-income group.5

Non-adherence to medicines was found as a common coping strategy for OOPE on medicines and polypharmacy, a finding consistent with other papers, which will have adverse consequences on patient outcomes.37

Strengths and limitations

Our paper is the first systematic review examining OOPE on medicines for multiple chronic conditions. We conducted an extensive search via medical and economic databases, including grey literature, through the use of precise search terms and application of stringent inclusion criteria.

A limitation was OOPE on medicines not being studied specifically with multimorbidity (eg, in association with Charlson Comorbidity Index, an indication of NCD severity, but not number of NCDs). Hence, there is a need to address these gaps in future studies by examining OOPE specifically, and how OOPE is associated with different numbers and types of NCDs. Another limitation was that most eligible articles examined numbers of NCDs without reporting the exact chronic conditions. Future studies should examine specific NCDs with a view to understanding which NCDs may yield higher OOPE on medicines.28 The number of NCDs and OOPE were mostly self-reported and may be subject to greater under-reporting of NCDs in persons from lower socioeconomic background.

Regarding quality assessment of included articles, the NOS is an established and well-used quality assessment tool for non-randomised studies. The NOS has potential limitations as questions over the validity of the scale have been raised,38 and we adjusted the NOS to meet our analysis, specifically altering the grading categories to match NCD measurement rather than a specific exposure, and remove questions relating to follow-up. Nonetheless, with a descriptive analysis, the NOS is very useful in providing comparison between studies reported, and our adjustments to the NOS are in line with assessing the key biases potentially present (including selection, measurement and representativeness).

Policy implications

Individuals suffering from multimorbidities may have greater OOPE on medicines due to their complex treatment needs. Despite increasing prevalence of multimorbidity, current health policies and clinical practices rely on a single-disease specific approach. This may suggest to policymakers to move from a single-disease framework to one that takes into account multimorbidity, when allocating funds and when designing policies aimed at financial protection. Low socioeconomic status groups whose high rate of NCDs and low incomes result in more price-sensitive behaviour, as well as being more sensitive to the ill effects of high cost sharing, may need priority attention.5 In addition to NCD multimorbidity, vulnerable groups may experience a double burden from NCDs and infectious diseases, which may drive patients into further impoverishment.39 Targeted government funding and support programmes should take into account multimorbidity status of individuals, particularly for the elderly and low-income groups who are most vulnerable to OOP hardships.

In considering a policy response to the financial burden and impoverishment from OOPE on medicines for multimorbidity, there may be a need for policy interventions to account for the underestimation of the problem in standard measures, owing to the impact of coping strategies (eg, non-adherence). For example, vulnerable and marginalised groups may not even seek healthcare and hence will not be prescribed medicines, resulting in the under-representation of the true extent of multimorbidity and potential implications for OOPE on medicines.40 Policy measures could include exemptions from certain costs for the elderly and low socioeconomic status groups, lower caps on copayments and subsidies for vital drugs. Prescription drug cost sharing benefit plans must be designed to provide enhanced and broadened coverage for multimorbidities, particularly for certain NCD combinations.

There are also important clinical implications of OOPE in patients with multimorbidity. The literature shows a trend that multimorbidity in family practice is now the norm rather than the exception.41 Clinicians need to consider the financial burden incurred by patients with multimorbidity due to polypharmacy, and the risks of non-adherence and foregoing medicines as coping strategies. Another crucial clinical implication relates to the need for better clinical prescription guidelines to minimise prescription of unnecessary medicines for chronic illness which may cause unwarranted expenditures on medicines by patients.6 42

Conclusion

Multimorbidity of NCDs is increasingly costly to healthcare systems and OOPE on medicines can severely compromise financial protection and UHC. The evidence reviewed here shows the relationship between multimorbidity and OOPE on medicines. It is crucial to recognise the need for better equity and financial protection, and policymakers must examine health system financial options, cost sharing policies and service patterns for those with NCD multimorbidities.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr Deirdre Hennessy and Dr Anna Kemp for providing additional study information.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: JTL, CM, and GS contributed to the conception and design of this research. GS performed the literature search and extracted data from individual studies. GS and TH conducted the data analysis and interpreted the data. GS wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors revised the first and subsequent drafts. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding: GS is funded by the President’s Graduate Fellowship, National University of Singapore. JTL is funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) Tier 1 Grant, Singapore. CM is funded by NIHR Research Professorship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Lancet NCD Action Group NCD Alliance. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet 2011;377:1438–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The United Nations. 2011 high-level meeting on prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. http://www.un.org/en/ga/ncdmeeting2011/ (accessed 15 Jan 2017).

- 3. World Health Organisation. Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013-2020. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-action-plan/en/ (accessed 15 Jan 2017).

- 4. Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ 2015;350:h176 10.1136/bmj.h176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaspers L, Colpani V, Chaker L, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:163–88. 10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JT, Hamid F, Pati S, et al. Impact of noncommunicable disease multimorbidity on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures in middle-income countries: cross sectional analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127199 10.1371/journal.pone.0127199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Safran DG, Neuman P, Schoen C, et al. Prescription drug coverage and seniors: findings from a 2003 national survey. Health Aff 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives:W5-152–w5-66. 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organisation. Universal Health Coverage and health financing. http://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/ (accessed 13 Jan 2017).

- 9. Kankeu HT, Saksena P, Xu K, et al. The financial burden from non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:31 10.1186/1478-4505-11-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dror DM, van Putten-Rademaker O, Koren R. Cost of illness: evidence from a study in five resource-poor locations in India. Indian J Med Res 2008;127:347–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wagner AK, Graves AJ, Reiss SK, et al. Access to care and medicines, burden of health care expenditures, and risk protection: results from the World Health Survey. Health Policy 2011;100:151–8. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muka T, Imo D, Jaspers L, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on healthcare spending and national income: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:251–77. 10.1007/s10654-014-9984-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bommer C, Heesemann E, Sagalova V, et al. The global economic burden of diabetes in adults aged 20-79 years: a cost-of-illness study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:423–30. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30097-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lehnert T, Heider D, Leicht H, et al. Review: health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev 2011;68:387–420. 10.1177/1077558711399580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valtorta NK, Hanratty B. Socioeconomic variation in the financial consequences of ill health for older people with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Maturitas 2013;74:313–33. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Federal Reserve Bank. Foreign Exchange Rates (annual). https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g5a/current/

- 17. U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Consumer Price Index. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables.htm

- 18. OECD Data. Average wages. https://data.oecd.org/earnwage/average-wages.htm (accessed 28 April 2017).

- 19. OECD better life index. Income. http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/income/ (accessed 11 May 2017).

- 20. Wells BS GA, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed 28 Jan 2017).

- 21. Higgins JP GS. Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crystal S, Johnson RW, Harman J, et al. Out-of-pocket health care costs among older Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000;55:S51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, et al. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff 2001;20:267–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sambamoorthi U, Shea D, Crystal S. Total and out-of-pocket expenditures for prescription drugs among older persons. Gerontologist 2003;43:345–59. 10.1093/geront/43.3.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gellad WF, Huskamp HA, Phillips KA, et al. How the new medicare drug benefit could affect vulnerable populations. Health Aff 2006;25:248–55. 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruger JP, Kim HJ. Out-of-pocket healthcare spending by the poor and chronically ill in the Republic of Korea. Am J Public Health 2007;97:804–11. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Aff 2009;28:15–25. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kemp A, Preen DB, Glover J, et al. Impact of cost of medicines for chronic conditions on low income households in Australia. J Health Serv Res Policy 2013;18:21–7. 10.1258/jhsrp.2012.011184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Campbell DJ, King-Shier K, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Self-reported financial barriers to care among patients with cardiovascular-related chronic conditions. Health Rep 2014;25:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park EJ, Sohn HS, Lee EK, et al. Living arrangements, chronic diseases, and prescription drug expenditures among Korean elderly: vulnerability to potential medication underuse. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1284 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pati S, Agrawal S, Swain S, et al. Non communicable disease multimorbidity and associated health care utilization and expenditures in India: cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:451 10.1186/1472-6963-14-451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park E-J, Kwon J-W, Lee E-K, et al. Out-of-pocket medication expenditure burden of elderly Koreans with chronic conditions. Int J Gerontol 2015;9:166–71. 10.1016/j.ijge.2014.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thorpe KE, Allen L, Joski P. Out-of-pocket prescription costs under a typical silver plan are twice as high as they are in the average employer plan. Health Aff 2015;34:1695–703. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hennessy D, Sanmartin C, Ronksley P, et al. Out-of-pocket spending on drugs and pharmaceutical products and cost-related prescription non-adherence among Canadians with chronic disease. Health Rep 2016;27:3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jung Y, Byeon J, Chung H. Prescription drug use among adults with chronic conditions in South Korea: dual burden of health care needs and socioeconomic vulnerability. Asia Pac J Public Health 2016;28:39–50. 10.1177/1010539515612906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu AZ, Jiang JZ, Reeves JH, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use and healthcare expenditures in the US community-dwelling elderly. Med Care 2007;45:472–6. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254571.05722.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA 2007;298:61–9. 10.1001/jama.298.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bygbjerg IC. Double burden of noncommunicable and infectious diseases in developing countries. Science 2012;337:1499–501. 10.1126/science.1223466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Devoe JE, Baez A, Angier H, et al. Insurance + access not equal to health care: typology of barriers to health care access for low-income families. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:511–8. 10.1370/afm.748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann Fam Med 2005;3:223–8. 10.1370/afm.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organisation. Promoting rational use of medicines: core components. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67438/1/WHO_EDM_2002.3.pdf (accessed 29 May 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2017-000505supp001.pdf (477.8KB, pdf)