Abstract

Introduction

In 2013, the Zambian Correctional Service (ZCS) partnered with the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia on the Zambian Prisons Health System Strengthening project, seeking to tackle structural, organisational and cultural weaknesses within the prison health system. We present findings from a nested evaluation of the project impact on high, mid-level and facility-level health governance and health service arrangements in the Zambian Correctional Service.

Methods

Mixed methods were used, including document review, indepth interviews with ministry (11) and prison facility (6) officials, focus group discussions (12) with male and female inmates in six of the eleven intervention prisons, and participant observation during project workshops and meetings. Ethical clearance and verbal informed consent were obtained for all activities. Analysis incorporated deductive and iterative inductive coding.

Results

Outcomes: Improved knowledge of the prison health system strengthened political and bureaucratic will to materially address prison health needs. This found expression in a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Health (MOH) and Ministry of Community Development, and in the appointment of a permanent liaison between MOH and ZCS. Capacity-building workshops for ZCS Command resulted in strengthened health planning and management outcomes, including doubling ZCS health professional workforce (from 37 to78 between 2014 and 2016), new preservice basic health training for incoming ZCS officers and formation of facility-based prison health committees with a mandate for health promotion and protection. Mechanisms: continuous and facilitated communication among major stakeholders and the emergence of interorganisational trust were critical. Enabling contextual factors included a permissive political environment, a shift within ZCS from a ‘punitive’ to ‘correctional’ organisational culture, and prevailing political and public health concerns about the spread of HIV and tuberculosis.

Conclusion

While not a panacea, findings demonstrate that a ‘systems’ approach to seemingly intractable prison health system problems yielded a number of short-term tactical and long-term strategic improvements in the Zambian setting. Context-sensitive application of such an approach to other settings may yield positive outcomes.

Keywords: health systems, health policy, public health, health systems evaluation

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

The Zambian prison health system is in a state of chronic emergency.

Previous research has identified a series of governance, financing and capacity-related health system weaknesses that undermine both access to, and quality of, healthcare in Zambian prison facilities.

A health system strengthening project addressing macro, meso and microlevel reform was conducted in partnership with the Zambian Corrections Service between 2013 and 2016.

What are the new findings?

Framing this endeavour as a ‘health systems strengthening’ endeavour created space to address structural, particularly governance, factors that underpinned poor health system outcomes.

While not a panacea, findings demonstrate that the combination of strategic and tactical activities enabled modest progress to be made against overwhelmingly large and seemingly intractable problems.

The study further provides an example of how a pragmatic evaluation that draws on aspects of theory-driven design can be used to shed light on the outcomes of complex health system interventions.

Recommendations for policy

Context-sensitive application of these principles to other settings may yield positive outcomes by helping policy makers and corrections officials imagine possibilities for addressing entrenched barriers to improving prisoner health, including governance challenges at the macro level, and facility-level water and sanitation issues, poor inmate health literacy, and monitoring and follow-up for care and treatment.

Introduction

There is good evidence to demonstrate that the health of incarcerated populations globally is worse than that of the wider (non-incarcerated) community.1 These disparities in physical, mental and social health have been linked to socioeconomic and behavioural factors, including poverty, higher rates of alcohol and substance abuse, and higher rates of infectious disease and mental illness, with the last contributing to increased risk of crime and repeat offending.2 However, most evidence relating to the health of incarcerated people, and the state of health services in prisons, comes from high-income settings. International and national policy makers are now paying more attention to incarcerated populations in low-income and middle-income settings.3–5 A recent review of tuberculosis (TB), HIV and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) in sub-Saharan African prisons highlighted a series of common weaknesses relating to prison health systems in the region. These weaknesses included lack of financing, cursory or absent policy frameworks, inadequate infrastructure, overcrowding linked to dysfunctional criminal justice processes, absent health information management systems, inadequate infection-control procedures, lack of transport to off-site clinics and profound fragmentation of care, among others.6 7 From a human rights and a public health perspective, there is an urgent need to address these issues, yet descriptions or empirical evaluations of interventions to improve health in low-income and middle-income prison settings remain rare.

In 2013, the Zambian Correctional Service (ZCS) partnered with the Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia (CIDRZ) on the Zambian Prisons Health System Strengthening (ZaPHSS) project.8 The project aimed to strengthen structural, organisational and operational weaknesses within the prison health system.9 Project aims were underpinned by formative and cooperative research conducted by ZCS and CIDRZ prior to the start of the project, which explored and elaborated on the health and health service conditions in Zambian prisons. Findings from that work highlighted a series of profound and systemic challenges, including weak or absent governance processes for prison health, limited health management capacity, chronic under-resourcing and the regular breakdown of basic health service availability for inmates.10–12 A ‘systems’ approach, which recognised the complex interaction between structural, environmental, organisational and personal factors driving health behaviours and health service outcomes, was thus deemed appropriate for the project.

The aim of this paper is to present the results of an overarching evaluation of the achievements and shortfalls of the ZaPHSS project. While not resourced to be able to carry out a fully fledged, theory-driven evaluation testing and retesting programme theory,13 14 we tried to move beyond a purely instrumental log-frame matrix approach, in seeking evidence of both project achievements or ‘outcomes’, as well as reflecting on the contextual enablers and barriers and the catalytic mechanisms that underpinned those achievements.15 Such an approach has gained recognition as a more nuanced alternative to instrumental evaluations in circumstances where the intervention and the setting are complex. Such methods help enable programmers, policy makers and reviewers to collect data on what was achieved, and to help answer questions about how and why certain outcomes were observed in that setting.16–18

Project background

A broad-reaching description of the Zambian prison system has been published elsewhere.10 The overarching goal of the ZaPHSS project was to strengthen the health system by improving the capacity of the ZCS to deliver quality healthcare for prison inmates.

The project sought outcomes at three levels—policy, management and prison facility level. Due to the project’s initial 3-year duration, change at the facility level was sought within 11 of Zambia’s 87 stand-alone prisons, which included both male and female holding facilities, and the largest and most overcrowded prisons in Zambia. Specifically, the project sought to do the following:

support the formation of high-level, multisectoral prison health governance mechanisms capable of providing strategic guidance and investments in prison health

strengthen the capacity of existing mid-level (ZCS) governance structures, including the ZCS Health Directorate, to plan, implement and monitor prison health services

support the formation of facility-level structures capable of advocating for, maintaining accountability of, and supporting front-line prison health services.

Although there was inevitable overlap during implementation, the project was conceptualised in three phases that broadly mapped onto the three objectives listed above. The first phase of the project was devoted to a series of knowledge-generating and capacity-building opportunities (eg, workshops, meetings and high-level fora) to strengthen awareness, and motivate and mobilise a core group of high-level stakeholders from within key ministries (Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), Ministry of Health (MOH), Ministry of Community Development (MCD)) and ZCS. The project envisaged these key stakeholders would be responsible for carrying out important, often complex actions, including negotiating a Memorandum of Understanding, coproducing strategic plans and redirecting finite prison resources to health-related activities.

In the second phase, the focus was on strengthening management structures and strategic planning within ZCS, via a series of targeted workshops to build capacity in (among other things) health needs assessment, monitoring and evaluation in a low-resource environment, budgeting, and media training. These processes culminated in a series of prioritisation and action-planning exercises to identify key areas of health system weakness (eg, recruitment and retention of human resources for health) and options for strengthening facility-level health services (eg, via formation of facility-based health committees). The final phase saw the project shift focus to prison facilities, specifically the establishment and development of systems of support for establishing prison health committees (PrHCs). These were new bodies constituted at the facility level in 11 target prisons, with approval from ZCS and other key stakeholders during the first two phases of the project.

The total funding for this project was £660 000 disbursed over 4 years. In keeping with its focus on building capacity rather than developing parallel structures or investing in short-term services that could not be maintained post project, the ZaPHSS project team consisted of three full-time employees (a project manager, project coordinator and driver), and a director and technical advisor whose contributions were largely in kind. The project manager and coordinator were responsible for organising a continual series of awareness-raising forums and dissemination events across both phases of the project. In contrast to many health-related projects whose focus is on service and training outputs, the core of the project manager’s role was day-to-day engagement and relationship building with, and between, key prison stakeholders in government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). This relationship building and strengthening of communication and trust were essential since many of the project’s ‘outputs’—such as the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) or terms of reference for the PrHCs (discussed further below)—were not within the project’s direct control. Emphasis was thus on strengthening both hard and soft aspects of prison health governance that would enable ZCS to better leverage existing resources, while strengthening capacity to advocate for improved resourcing for prison health.

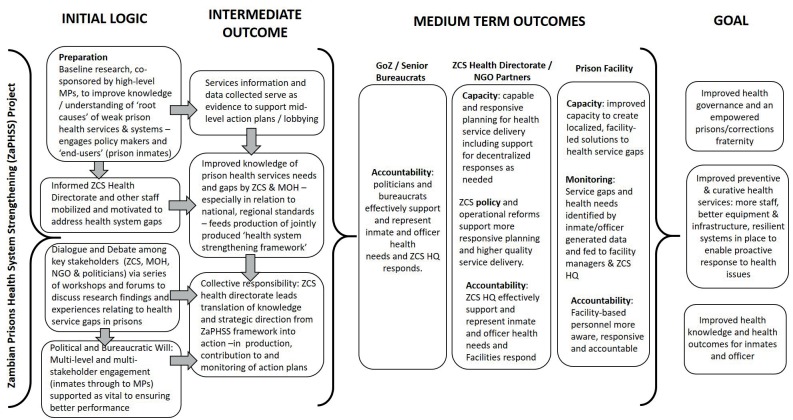

The basic project logic is outlined in figure 1. Phase 1 was focused on building key stakeholders’ understanding of the parlous state of inmate health, and relationship building among high- and mid-level stakeholders who had authority to influence those outcomes in various domains. This ‘awareness raising’ was intended to feed into more structured efforts to prioritise prison health system improvements by senior ZCS and MOH officials (eg, planning for human resources of health). Project staff aimed to facilitate this improved understanding and provide opportunities to discuss and formulate reform plans by hosting workshops, meetings and forums that provided space and opportunities for discussion and collaboration, which had previously been absent. Agreement by high-level officials in different ministries and units regarding their respective responsibilities for prison health, and priorities for improving the prison health system, would be documented in instruments such as a Memorandum of Understanding and a prison health system strengthening framework. In planning the project, ZaPHSS staff aimed to strengthen aspects of government stakeholders’ accountability, by ensuring that decisions and commitments made by senior decision makers at the various forums were transparent (available in public documents) and through promoting follow-up of those commitments by diverse stakeholders. The documents were also seen as forming a road map to guide the development of action plans that incorporated both prison headquarters and facility-based interventions during phases 2 and 3. Interventions would be determined in part by the identified priorities, but would revolve around capacity-building for health service planning and management among key ZCS personnel (eg, training in rapid health needs assessment and monitoring and evaluation in phase 2) and the design and implementation of instruments to strengthen facility-level health services (eg, the formation and training of PrHCs in phase 3). These activities would simultaneously establish a more robust chain accountability from inmates and front-line health service providers through to the ZCS Director of Health. Iterative improvements in environmental and health service arrangements achieved at the facility level would be complemented by improved planning and resourcing achieved by advocacy and management contributing to overall improvements in access to quality care, health knowledge and health outcomes among inmates and officers.

Figure 1.

ZaPHSS programme logic. GoZ, Government of Zambia; HQ, Head Quarters; MOH, Ministry of Health; MP, Member of Parliament; NGO, non-governmental organisation; ZCS, Zambian Correctional Service; ZPS, Zambian Prison Services.

Methods

Evaluation framework

This evaluation collected data on project outcomes, and sought information on the catalytic mechanisms and the enabling (or otherwise) contextual factors that influenced those outcomes. While the project lacked resources to invest in a fully fledged, theory-driven evaluation that would have required testing the project’s action and causal models and translating findings into a refined programme theory,13 14 we drew on principles of this method to design a feasible cross-sectional evaluation that sought to answer not just whether the project had impact, but what tangible and intangible factors contributed. Using the programme logic in figure 1 as the basis for assessing project impact, we additionally sought information on the ‘mechanisms’ and ‘context’ that enabled such impact. Drawing on theory-driven evaluation literature, we understood ‘mechanisms’ as distinct from activities, rather representing the underlying processes that operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes.15 19 Specifically, we adopted Mukumbang et al’s20 characterisation of mechanisms as having three main characteristics, namely they are usually invisible, sensitive to variations in context and responsible for generating outcomes. Context was understood as both proximate and distal factors influencing the behaviours, decisions and actions of key stakeholders in the project.

Study procedures

For this evaluation we used a combination of document review and qualitative methodologies to reconstruct stakeholders' experiences and perceptions of ZaPHSS, and to identify factors contributing to project successes and shortcomings. Project documentation, including the project logic diagram, was used as a point of reference to better understand implementation fidelity and to evaluate success against the project’s own objectives. Complementary data were sought in the form of indepth interviews and focus group discussions to obtain the views and experiences of key stakeholders from every level of the prison health system, and are outlined in table 1 and below.

Table 1.

Data collection summary

| Study population | Activity | Respondents (n) |

| ZCS headquarters | IDI | 7 |

| Ministry officials (health, home affairs) | IDI | 3 |

| NGO, other community stakeholders | IDI | 2 |

| Facility officers in charge | IDI | 3 female 4 male |

| PrHC members | FGD | 21 female 51 male |

| Non-PrHC members | FGD | 23 female 46 male |

Exclusion criteria for all categories were a respondent <18 years old and/or a known history of mental illness.

NGO, non-governmental organisations; PrHC, prison health committee; ZCS, Zambian Correctional Service.

Participant and non-participant observations were recorded in research memos as part of the ongoing ZaPHSS programme monitoring. Observations incorporated memos from prison visits, including observations regarding interactions, decision processes and relationship development related to prison health planning. Research memos were created as electronic files and coded for date, location and theme. Researchers also reviewed publicly available ZCS planning documents and coded information relating to documented priorities, plans and processes for health system strengthening.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) were carried out with corrections officers, officials from the MHA, MOH and MCD, and key stakeholders from civil society groups. Sampling was purposive and based on identification of respondents’ knowledge of, and involvement in, prison health policy or service delivery. Separate focus group discussions (FGDs) were carried out with members (comprising inmates and officers) and non-members (inmates only) of the PrHCs. FGDs were held in both male and female wings of all study facilities. Recruitment for FGDs was on a first come, first served basis with a minimum of eight participants in each case. In conjunction with the Officer In Charge, a study investigator issued an open invitation to attend one of two FGD sessions—one for PrHC members and non-members, respectively. Separate sessions were held for PrHC members and non-members in order to compare and cross-check experiences and perceptions of members and non-members. The Officer In Charge, or their delegate, at each of the six facilities provided an overview of the study to potential participants and referred those who were interested to a room designated for the FGD. At the meeting, a multilingual Zambian study investigator provided more detail about the study, invited and answered questions, and asked if the participant(s) were still willing to participate. Verbal informed consent was then sought in the participant’s language of choice (Bemba, English, Nyanja, Tonga).

IDI and FGD question guides were specific to the type of participant. Participants were interviewed or participated in focused discussions for approximately 1 hour. All IDI and FGD participants permitted audio recording for later transcription and analysis. No payments were made for involvement in any of the activities.

Data management and analysis

All audio recordings were transcribed directly into English in Microsoft Word along with expanded field notes. A research assistant fluent in all four languages compared the transcripts with audio recordings and assessed them for accuracy, completeness and compliance with formatting requirements. Any anomalies were addressed by the interviewer or facilitator supported by field notes. The principal investigator consulted the team to develop a thematic framework for data analysis using both inductive reasoning based on emerging themes and deductive reasoning based on a priori themes. A codebook was developed per the thematic framework to capture text related to different types of project outcome—material, relational and knowledge-based—and the mechanisms and contextual factors contributing to those outcomes. The principal investigator transformed the transcripts into projects for analysis and interpretation on QSR NVivo, and coded the documents and transcripts refining themes through inductive reasoning and judgements about the relevance, meaning and implicit connections. Indexed data were put into matrices corresponding to the a priori research enquiries on outcomes, mechanisms and context, clearly identifying the source of the data.

Ethical considerations

All project staff were trained in fundamental ethical principles and good research practices. The need to respect persons and their privacy was emphasised and constituted part of the standard operating procedures. Inmate identifiers were not collected. All written and digital records were kept in a secured and locked area. All computer entry and networking programmes were on password-protected servers with encrypted data. Analysis data sets were identified by study identifiers. Completed IDI and FDG transcriptions, notes and audio recording are kept confidential.

Findings

We present findings in the categories of ‘outcomes’ ‘mechanisms’ and ‘context’. Within the ‘outcomes’ section, and in order to facilitate reflection on the health system strengthening impacts of the project, we grouped findings according to three health system components21 of (1) governance, leadership and management; (2) human resources for health, and (3) health service and environmental health outcomes. A final component of the outcomes category additionally reflects on project challenges and shortcomings.

Project outcomes

I think this project is unique because it is there to stay. It is not a temporal program. It is there to stay […] It is forming a system where even if today the Officer In Charge is changed and someone comes in, the system remains the same. It will be there forever. (Official 1, Zambian Prison Service)

Governance, leadership and management

A number of outcomes related to governance, leadership and management were identified from stakeholder interviews and document analysis, as outlined below.

Project documentation and interview data flagged two important instruments of governance arising from the project. First was the development and signing of a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding between the MOH, MHA and the MCD.i This MOU articulated and formalised the responsibilities and commitments of the various ministries vis-à-vis prison health, and was viewed as having an important role in promoting institutional accountability in the future.

[ZaPHSS] really helped Zambia Prison Service. First and foremost, it has really linked Zambia Prison Service and Ministry of Health, helping them work together [via] the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding. (Official 1, Ministry Home Affairs)

The second governance innovation was the appointment of a high-ranking MOH focal-point person for prison health, responsible for working with the ZCS Command to ensure coordination and cooperation between the two ministries. As noted in one project report:

The [focal-point person] has become a leader in the process of strengthening the collaboration between the ZCS and MOH. For example, the action of appointing the focal point person has seen the commencement of the first ever process formally linking prison facilities and their respective District health offices […] A critical achievement since this relationship and the awareness and communication it will promote are an essential baseline for future collaborative actions by ZCS and MOH. (ZaPHSS Annual Report: 2016)

A further governance outcome included the establishment of more robust management processes for prison health planning within ZCS. Key among these was the generation of the ZaPHSS Framework—a strategic document identifying priority areas for health system strengthening action over a 5-year (renewable) period—and an action plan arising from it. Critically, these documents proposed a revised (although aspirational) structure for prison health management, including a series of new posts in the Health Directorate to support management and planning. This blueprint for staffing was included in a ZCS submission to the Cabinet in November 2016, with six of the newly proposed health-specific positions subsequently approved by the Cabinet; these new positions included Director of Health Services, Health Professional (Deputy Director), two HIV/AIDS coordinators and two clinical care officers.

The advantages of these improved governance and management structures within the ZCS Health Directorate were commented on by other NGO partners working with ZCS, such as the official quoted below:

The programs we were doing with Prison Service, we had difficulties in getting the Prison Service to reorganize the structures itself. To have a program which was structured [was really difficult] because ZCS health [itself] had no structure. But with the ZaPHSS program we saw the advantage to our [NGO] work as it could be channelled through [the new ZCS] structure which was sustainable. And the structure and systems remain [even if] people change. So, having structures in place became a[n]advantage for our project work […] It became like a platform, or a stepping stone. (Official 1, NGO Partner)

The ZaPHSS Framework also formalised terms of reference for a new facility-level body, the PrHC, incorporating both inmates and officers, with a health promotion and monitoring remit as outlined in box 1. PrHCs constituted an important governance outcome, providing a safe space for interaction between inmates and officers and the localised prioritisation of health needs.

Box 1. Formation of the prison health committees (PrHCs).

During the first and second phases of the project, ZCS and other stakeholders debated the necessity and appropriateness of constituting a facility-level health committee that could monitor, report and ensure linkage of inmates to health services. In 2013, a working group comprising representatives from ZCS, Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Health formalised and published a terms for reference for PrHCs and approved the subsequent establishment of the first 11 PrHCs in nominated prisons. Key features of the committees included the comembership of both officers and inmates; a remit for both health promotion and service accountability; and a published terms of reference in support of their duties disseminated to all Officers in Charge by ZCS headquarters. Membership was by appointment and all committees reported directly to the Officer in Charge.

Tangible improvements in health conditions at the six surveyed sites arising from PrHC planning, advocacy and implementation included improved environmental health conditions via new garbage disposal protocols, hygiene promotion activities and sanitation measures; and strengthened knowledge and capacity of inmates and officers to identify and address health concerns.

Interview and focus group data also documented a range of reported improvements in health service access and health outcomes such as strengthened processes for ensuring access and adherence to chronic care processes (primarily HIV and TB) and reported reductions in rates of common communicable diseases.

TB, tuberculosis; ZCS, Zambian Correctional Service.

In reflecting on some of the conditions that promoted these various governance outcomes, participants pointed to the importance of improved understanding of the dire state of prison health and the prison health system among decision makers both outside and inside the prison system. Strengthening awareness of these issues was an iterative process, involving an ongoing series of meetings, workshops and trainings over the course of the 4-year project, aimed at promoting cross-sectoral discussion around prison health and health systems. Interview data highlighted how these activities improved awareness among government officials, providing impetus for decisions to engage in planning and foster partnerships:

The program brought […] general awareness of the health needs in Prisons to even non-medical personnel. Since a number of the project activities included even non-health personnel to share in the [training and thinking]. I think it broadened their perception of what the health system is […] It broadened our scope of thinking when facing these challenges. (Official 3, Zambian Prison Service)

You know […] sometimes you may not realize what you want until you really tabulate the needs. It is all about the background of understanding what we need and taking a futuristic [forward planning] approach. (Official 3, Zambian Prisons Service)

Human resources for health—capacity and competency

An important outcome from the ZaPHSS project was the strengthened recruitment and training structures for ZCS-employed health personnel. Arising from the project strategic and action-planning activities, ZCS developed a programme of targeted recruitment of (already trained) health professionals during the annual officer intake. Over 24 months, this resulted in a doubling of the health professional capacity within ZCS ranks (34–78) between 2014 and 2016. These numbers discounted a further seven officers enrolled in nursing school following the establishment of a relationship between the ZCS Health Directorate and a graduate nurse school in northern Zambia.

It has been a great achievement [to improve human resources] even though the numbers are still small. The recruitment of thirty-three (33) new health staff plus those that are recently graduating from the training school in prison; that activity has helped with our health service delivery very much. (Official 1, Ministry Home Affairs)

Challenges and shortcomings

Notwithstanding the outcomes described above, a series of project challenges and shortcomings were identified when it came to health system strengthening. Primary among these was the ongoing issue of ensuring central-level support for improved resourcing of prison health. Despite a documented increase in funding for prison food in financial year2016, efforts to strengthen the capacity of those responsible for advocating for increased disbursements—a stated objective of the project—were stymied by complex and often high-level political considerations that lay beyond the reach of the project team. The low priority given to prisoner welfare in the context of multiple competing demands for public funds in Zambia, for example, was a critical barrier.

You know currently we have great ‘goodwill’ from government. But I think the ‘political will’ to address these issues is not there. Because you need political will to overcome this terrible congestion that we have […] the poor sanitation, poor water [and] infections that are spread due to these things. OK so […] as much as we have the goodwill and these emotional outbursts from politicians who say: ‘Let us do it,’ I do not see [action]. (Official 3, Zambia Prisons Service)

The project was also unable to achieve several mid-level outcomes that would have facilitated Parliamentary-level action to address the resourcing shortages. These included a failure to achieve revision of the Prisons Budget or ‘yellow-book’ to ensure dedicated and disaggregated health service line items. Lack of progress in this domain meant that the weak resourcing of prison health identified at the project’s inception10 remained a fundamental impediment to planning or delivery of quality health services at the project’s close. As one respondent noted:

The challenges are structural […] and a big one is the issue of funding from the government. It is not sufficient. (Official 1, NGO Partner)

A further challenge was weakened participation by the Ministry of Community Development Mother and Child Health (MCDMCH) following the loss (c.2015) of its mandate over the Mother and Child Health portfolio and with that, district-level health services. This authority returned to MOH, and MCDMCH subsequently discontinued participation in many of ZaPHSS’ mid-level forums. Yet the participation of MCD in the prison fora—including along the lines outlined in the Memorandum of Understanding—remains vital since the ministry retains the responsibility for social welfare, which facilitates prisoner transition to the local community, including continuity of care in the mainstream health system.

The project struggled with lack of sufficient internal (ZCS) human resources capacity in the ZCS Health Directorate. Indeed, at project close the Health Directorate was not only no stronger in terms of allocated manpower, it had lost one of the few long-term appointees to an internal transfer. Despite Cabinet approval of six new Health Directorate positions, lack of resourcing to activate these positions meant that the ZCS Health Directorate at time of writing remained largely overwhelmed by the task of administrating healthcare in Zambian prisons. With so few personnel, and with over 50 lock-down facilities, continued lack of capacity in the Health Directorate remains a critical, potentially debilitating barrier to basic budgeting, monitoring, planning and oversight functions. As noted by one ranking ZCS officer:

The prisons service is incapacitated […] when it comes to health personnel. We have so few. (Official 1, Zambian Prison Service)

While the project was able to tackle some elements of weak prison health systems, therefore, the sustainability of these reforms is, as yet, unproven. Moreover, the circumstances described above mean that uneven, project-driven improvements to the facility health service landscape (rather than strategic, system-led reform) will likely remain the norm in Zambia’s prisons in the short-to-mid-term.

Mechanisms

As noted previously we define mechanisms as ‘the underlying social drivers of behaviour’ that are usually invisible, sensitive to variations in context and responsible for generating outcomes.20 Using this definition, we identified three sets of mechanisms, operating variously to spur decisions or actions by policy makers, administrators and PrHC members who contributed to the above-described impacts.

Communication

Improved communication between ministries, bureaucrats, non-governmental groups, and (at the facility-level) inmates and officers was consistently identified as a catalyst for the health system gains made during the project. Communication was linked to improved relationships that developed and strengthened over the course of the 4-year project via a series of collaborative workshops and meetings designed to ensure consistent cross-sectoral representation. Interview data combined with programme experience pointed to the importance of these opportunities for formal and informal information sharing and a gradual breakdown of existing and long-standing institutional suspicions, as noted by one official:

ZaPHSS has really worked well […] It has brought us together. Things are working out well between the Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Health and the prisons. If it was not for ZaPHSS we could have still been working in isolation. (Official 1, Ministry Home Affairs)

At the prison facility level, both members and non-members of PrHCs reported important improvements in inmate–officer relationships arising from the activities and relationships forged in the committees. Opportunities for inmates and officers to communicate and collaborate in the context of the PrHCs were described as improving dialogue and understanding between the two populations, as described by a PrHC member below:

CM7: We are seeing the positive relationship between the officers and the inmates. These people in this [PrHC] committee are showing a lot of zeal to work and this thing will help us a lot. (Male PrHC Member, Facility 4)

Trust and coproduction

Improved and more frequent communication via various projects, joint production of various outputs and the resultant strengthening in individuals’ understanding of each other’s and inmates’ health needs provided a self-reinforcing basis for improved interpersonal trust. This occurred between government officials where ongoing and iterative policy discussions encouraged more forthright discussion of problems and opportunities, with gradual improvements in individuals’ ability to speak honestly about their perspective:

The [ZaPHSS] programme brought the three Ministries together closer than before, […] in much more coordinated a way. You know, today the Ministry of Health can stand and speak and state that they want to implement or to enhance what is already in existence in our prisons, which never used to happen. […] The Ministry of Health has always been there, you see, but now today they can stand and speak and that is down to the project. (Official 3, Zambian Prisons Service)

Trust was strengthened at the facility level, between inmates and officers, with respondents describing the central role played by PrHCs. Prior to the establishment of the PrHCs, there was no legitimate forum in which inmates and officers could exchange information. Both inmates and officers risked opprobrium if they were caught ‘fraternising’. The creation and central authorisation of the PrHCs provided safe space for communication between the two, a low-risk environment that built perceptions of sincerity and fairness among the different committee members:

My feelings changed because of the work we are doing. I saw the good spirit that we, the committee, have and the help inmates are receiving. […] I was humbled by the officers also, they are really down to earth, we are working as colleagues not as a prisoner and an officer. (Female PrHC Member, Facility 2)

The knowledge I have gotten from the inmates (in the PrHC) is so encouraging. This is why we have seen many illnesses reducing in this facility. This is so because of the inmates we are working with […] What I have seen in here has really made me learn a lot of things and I see hope. (Male Officer PrHC Member, Facility 2)

Several stakeholders commented on the role that ZaPHSS played in facilitating shared spaces in which various stakeholders—government, non-governmental, inmate representatives and corrections officials—could discuss and plan in a coordinated manner. This included the ability to align technical programmes (eg, HIV testing) with broader strategic priorities identified by ZCS in the process of developing the ZaPHSS framework:

Other NGO programs have tended to focus more on specific technical interventions which if they stand alone they will collapse and die. What you have done as ZaPHSS is to build a sustainable system through which these other technical areas would exist. That is the difference. Because you put the structure in place that allow us for these programmes to function. (Official 1, NGO Partner)

Collective voice and empowerment

At the facility level, the power of collective voice—enabled by the formation and sanctioning for PrHCs—and a sense of empowerment derived from participating in a body that had access to decision makers were described by inmates and officers as important mechanisms underpinning improvements brought about by the PrHCs.

What I know is that, the way the committee works is that, the communication or in terms of making the decisions, it is a collective. In other words, they are the ones on the ground, so what happens is that when they observe something or if they say there is a problem, they are able to bring it out to the attention of the officers […] If I can call it as a ‘bottom up’ approach to decision making, because they are the ones on the ground and they are the ‘senses’. (Officer In Charge, Facility 3)

Context

The context in which project activities are conducted can be critical to enabling mechanisms to ‘fire’.15 Drawing on experience and observations of the project investigators as well as interview and focus group data, we identified five major contextual factors, as summarised in table 2. These factors included, first, the presence of a series of legally mandated (if not fully realised) structures that provided a basis for a ‘health system strengthening’ in prisons. An example was legislation specifying the need for functional prisons Health Directorate, which formed the basis for efforts to strengthen that body and improve its capacity. Second, a favourable political backdrop in which high-level officials such as the Vice-President (at the time) were publicly articulating the need for improvements to prison conditions. Third, an operational backdrop in which the Zambian Prisons Service was transitioning to the ZCS and a ‘corrections’-oriented approach, informed by international standards such as the Mandela Rules. These rules emphasised the inmates’ right to health and healthcare. Fourth is an existing platform for civil society engagement and collaboration in the prison health system. Finally, a recent history of CIDRZ engagement with and support for health services in Zambian prisons played a role by facilitating the project’s access to high-level and often extremely busy corrections officials.

Table 2.

Contextual factors contributing to ZaPHSS success

| Contextual factor | Explanation | Significance to this evaluation | Illustrative quotes |

| Existing structures promoting prison healthcare | ZaPHSS interacted—and dovetailed—with government-created mechanisms for improving prison health (eg, the ZCSHealth Directorate and existing legislation and regional standards promoting better inmate health). |

|

“The [existence] of the Prisons Directorate of Health Services was one important factor [helping the project] cause then you had an entry point. Prior to that, you were talking to the HIV coordinator the other time you were talking with the Deputy Commissioner. The other time the Commissioner. So you did not really know what your entry point was and everyone wanted to be involved but without any direct focus. So the Directorate of Health Services in the Zambia prison service was an important thing that it happened and it helped.” (Official, Ministry of Health) |

| Favourable political backdrop | The Vice-President visited prison and made prisons a national story in 2014 with widely reported quote that Zambian prisons were ‘hell on earth’. This galvanised political support for action. |

|

“The Ministry of Home Affairs, they were very supportive. They created the platform for us to engage the prison service […]” (NGO Official) “I think it is the buy-in from Prisons, there was a felt need within the Prisons. Also within the government, there was a felt need that the health systems in Prisons needed to be improved. With these two facts […] you had an entry point.” (Official, Ministry of Health) |

| Favourable operational backdrop | Shift from punitive to ‘corrections-based’ approach within the Zambian prison service |

|

“It is only now that the issue of prison health is taken seriously because of the paradigm shift that has taken place, the whole world which has been transformed from punitive to correctional approach and which involves quality health care.” (Official 1, Zambian Prisons Service) “You know how we operate. Once there is acceptance from the top, there is acceptance through to the bottom.” (Official 3, Zambian Prison Service) |

| Existing civil society buy-in |

Other NGO partners (UNODC*/SHARE II†) acted as important intermediaries using their institutional legitimacy to facilitate ‘relationships, conditions and spaces’ for debates and activities. |

|

“ZaPHSS continued strengthening its relationship with other key prison stakeholders, particularly UNODC which co-funded PHAC Retreat of June 2015 along with other NGO parnters SHARe II project.” (Annual Report, Yr 2) “Apart from the MCDMCH and MOH being instrumental members of the technical working group that developed the ZaPHSS Framework, both attended the Prisons High Level Advocacy Meeting convened by UNODC and the ZaPHSS project.” (Annual Report, Yr 3) |

| CIDRZ reputation and access to resources | Long-term presence in prisons with established relationships between ZCS Health Directorate and CIDRZ TB unit |

|

“The trust between Zambia Prison Service and CIDRZ is there when you look at how CIDRZ has been supportive. When we started the TB program CIDRZ [in 2009/10 it] really worked well, the description of ZaPHSS and how it was going to work really gave hope to the Prisons Service. So there was trust already built so there was no doubting each other.” (Official, Ministry Home Affairs) “I think the issue of creating trust with the prison command and the officers was critical; this includes the officers in charge and the entire command and also the way CIDRZ followed the guidelines of operating in prison. [And] the other thing is financial commitment, CIDRZ really committed their finances towards this project.” (Official, Zambian Prison Service) |

*UNODC, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (https://www.unodc.org/).

†SHARE II, Support to the HIV/AIDS Response in Zambia (http://jsi.com/JSIInternet/IntlHealth/project/display.cfm?ctid=na&cid=na&tid=40&id=7481).

CIDRZ, Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia; HD, Health Directorate; MCDMCH, Ministry of Community Development Mother and Child Health; MOH, Ministry of Health; NGO, non-governmental organisation; PHAC, Prisons Health Advisory Committee; TB, tuberculosis; ZaPHSS, Zambian Prisons Health System Strengthening; ZCS, Zambian Correctional Service.

Discussion

ZaPHSS has been different in that it has been looking in a holistic way and capacity building, and coordinating the other players. That is what has been making it different. Because these other stakeholders have been looking at the small issues while ZaPHSS has been looking at the bigger picture. (Official 2, Zambian Prison Service)

This paper presents findings from a project evaluation conducted in the Zambian prison system between 2013 and 2015. It describes a mixed picture with respect to the overall health system strengthening outcomes. On the one hand, the project was able to impact both soft and hard aspects of high-level governance of health in prisons. Multiple participants from across various ministries and non-governmental groups consistently described improved understanding and awareness of prison health needs among high-ranking bureaucrats and Members of Parliament. Improved awareness, in conjunction with engineered opportunities to interact, promoted trust and helped catalyse the establishment of formal interministry agreements such as the MOU on prison health. Soft communication channels—such as the appointment of a prison-point person in the MOH—were also established and improved information sharing and decision making. Tangible impacts of these improved governance processes have included the now-routine involvement of prison officials in the annual MOH district-level budget planning.

The adoption of several new strategies to bolster human resources for health in prisons, an identified area of weakness for Zambian prisons,10 was the product of project-sponsored strategic planning and action workshops. Implementation of these strategies resulted in more than doubling of professional health workers employed by ZCS during the first 3 years of the project, with flow-on effects for staffing in some of the busiest prisons. There is debate over the appropriateness of strategies that increase the number of prison-employed health workers versus a health sector-led approach. Previous research in Zambian prisons11 12 and elsewhere22 23 indicates that the dual mission of delivering healthcare and serving a corrections mandate can result in the breakdown of high-quality, value-driven healthcare. At the same time, the investigators’ experience in Zambian prisons highlights other considerations. These include the difficulty of putting in place robust secondment or outreach arrangements for MOH personnel given, on the one hand, frequently variable security requirements, and on the other hand workforce considerations that include uneven access to professional development and promotion opportunities for MOH staff seconded to prisons. Further challenges include low levels of trust and weak communication channels between front-line MOH and corrections personnel that still result in breakdowns in inmates’ access to services.

From an extremely low baseline, the ZaPHSS project also contributed to a number of improvements in environmental health conditions and health service arrangements at the facility level. Modest improvements in the availability of human resources for health helped strengthen service access in several prisons. In the facilities surveyed for the evaluation, improved processes for TB symptom notification, and problem solving and information sharing to address ongoing environmental health issues, were clear outcomes of the newly established PrHCs. These committees strengthened facility-level communication and relationships by providing a sanctioned space for inmates and officers to discuss recurring issues and codevelop solutions based on locally available resources. Further exploration of these committees and the mechanisms through which they were most effective should be the subject of further study. While no panacea, the evaluation demonstrates systems-based impacts that constitute small but meaningful steps towards the idea of a ‘health promoting prison’.24–26

Despite some obvious project achievements, the overall health system strengthening efforts of the project were not uniformly successful. Failure to impact on domestic financing for prison health, for example, was the result of inability to meaningfully build skills and confidence within ZCS and the MHA for internal budget planning and advocacy that would allow prison officials to take advantage of domestic financing opportunities. The experience of project staff was that prison officials were generally poorly capacitated and empowered as compared with their Ministry of Health and Finance counterparts, with limited time or ability for bureaucratic manoeuvres. Nonetheless, as noted during baseline evaluations,10 improved health resourcing remains critical for Zambian prisons, and lack of progress in this domain has the potential to undermine the sustainability of other gains. Specifically, the ability of ZCS to plan and act to improve prison health services independent of donor-funded projects remains limited.

While elaborating and refining a theory of change lay beyond the scope and resources of this particular evaluation, the data point to several mechanisms and contextual factors that seem likely to have influenced project outcomes. Strengthened communication was a critical catalyst for project outcomes, particularly governance outcomes at the interministry and prison facility level. Such communication was enabled by a combination of the permissive political atmosphere at the time, combined with strong reputational standing and institutional trust between CIDRZ and ZCS based on previous work together.27–29 Together these factors promoted responsiveness by government officials to project suggestions and requests, particularly with regard to the need for multiple, intersectoral discussions about prison health needs and appropriate strategies. Building on the opportunities for communication, we found improved trust, coproduction and collective action to be mechanisms that underpinned outcomes such as the production of the ZaPHSS Framework, the MOU and the formation of the PrHCs. Positive perceptions of these outcomes fed virtuous cycles of interaction and action between previously isolated (even antagonistic) government stakeholders. The iterative, contingent and fragile nature of the relationship and trust building experienced in this project mirrors analysis and theory from other capacity-building efforts in a range of fields.30–32

Study limitations and strengths

Data for this study were largely collected by project staff, introducing the potential for positive bias in outcome evaluation. In particular, we acknowledge the potential for desirability bias among respondents who were inclined to praise a project that brought funding and support. While outsourcing evaluation activities may have mitigated this problem, issues of trust and access to hypersecurity-aware respondents would likely have undermined our ability to conduct such interviews at all. In this instance, investigator involvement in the project was important both for the ability to access those key stakeholders involved, as well as for the critical insight into the way project activities interacted with the broader context highlighting the contingent, embedded and iterative nature of the achievements in situ.33 As is necessary in any implementation and evaluation research of this type, we engaged in careful and reflexive interpretation of project data that constituted an important risk mitigation technique along with systematic consideration and reporting of both impacts and challenges throughout.

Conclusion

Health system strengthening literature has historically focused on process and outcome reporting often using instrumental approaches such as log-frame evaluations. In this paper, we sought to move beyond a process-driven evaluation to identify the mechanisms and contexts that underpinned project outcomes, drawing on the principles of theory-driven evaluation. Findings presented above provide the basis for some cautious optimism that, from an extremely low baseline, a system strengthening approach (elsewhere referred to as a ‘settings’ approach) can achieve progress towards improved health system and health service performance in high-needs settings like the Zambian corrections system. While acknowledging the manifest needs of the Zambian correctionshealth system, findings demonstrate how the combination of strategic and tactical activities can enable progress to be made on overwhelmingly large and seemingly intractable problems. Experience suggests that it would be impossible and unhelpful to try to reproduce this intervention with total fidelity, since many elements of the project evolved to address the unique attributes of the Zambian context. Nonetheless, context-sensitive application of these principles to other settings may yield positive outcomes by helping others imagine possibilities for addressing entrenched barriers to improving prisoner health, including water and sanitation issues, poor inmate health literacy, and monitoring and follow-up for care and treatment.

Footnotes

Previously known as the Ministry of Community Development Mother and Child Health.

Handling editor: Valery Ridde

Contributors: SMT, CNM and GH designed the study. SMT and CNM helped to collect data. CC and GW provided advice and guidance in the oversight of all project and study activities. SMT wrote the first draft with assistance from AS and CNM. All authors reviewed and provided critical edits.

Funding: This study was funded by the European Union under grant DCI- NSAPVD/2012/309-909.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality stipulations under the University of Zambia and University of Alabama at Birmingham IRBs, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. WHO. Prisons and Health. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organisation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet 2011;377:956–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rich JD, Beckwith CG, Macmadu A, et al. Clinical care of incarcerated people with HIV, viral hepatitis, or tuberculosis. Lancet 2016;388:1103–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30379-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubenstein LS, Amon JJ, McLemore M, et al. HIV, prisoners, and human rights. Lancet 2016;388:1202–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30663-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Telisinghe L, Charalambous S, Topp SM, et al. HIV and tuberculosis in prisons in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2016;388:1215–27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30578-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hatwiinda S, Topp SM, Siyambango M, et al. Poor continuity of care for TB diagnosis and treatment in Zambian Prisons: a situation analysis. Trop Med Int Health 2017. 10.1111/tmi.13024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Topp SM, Moonga CN, Luo N, et al. Mapping the Zambian prison health system: An analysis of key structural determinants. Glob Public Health 2017;12:858–75. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1202298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moonga C, Chileshe C, Magwende G, et al. Strengthening prison health systems: Feasibility and challenges of introducing prison health committees (prhcs) in zambian correctional facilities. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:A65.1–A65. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000260.174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mooya B. Zambia’s prisons health system receives a boost. Zambia Daily Mail 2015. https://www.daily-mail.co.zm/?p=29198 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Topp SM, Moonga CN, Luo N, et al. Mapping the Zambian prison health system: an analysis of key structural determinants. Glob Public Health 2017;12:1–18. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1202298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Topp SM, Moonga CN, Luo N, et al. Exploring the drivers of health and healthcare access in Zambian prisons: a health systems approach. Health Policy Plan 2016;31 10.1093/heapol/czw059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Topp SM, Moonga CN, Mudenda C, et al. Health and healthcare access among Zambia’s female prisoners: a health systems analysis. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:157 10.1186/s12939-016-0449-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen H-T. The conceptual framework of the theory-driven perspective. Evaluation and Program Planning 1989;12:391–6. 10.1016/0149-7189(89)90057-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Belle SB, Marchal B, Dubourg D, et al. How to develop a theory-driven evaluation design? Lessons learned from an adolescent sexual and reproductive health programme in West Africa. BMC Public Health 2010;10:741 10.1186/1471-2458-10-741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, et al. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci 2015;10:49 10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cornish F. Evidence synthesis in international development: a critique of systematic reviews and a pragmatist alternative. Anthropol Med 2015;22:263–77. 10.1080/13648470.2015.1077199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mukumbang FC, Van Belle S, Marchal B, et al. An exploration of group-based HIV/AIDS treatment and care models in Sub-Saharan Africa using a realist evaluation (Intervention-Context-Actor-Mechanism-Outcome) heuristic tool: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2017;12:107 10.1186/s13012-017-0638-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marchal B, Dedzo M, Kegels G. A realist evaluation of the management of a well-performing regional hospital in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:24 10.1186/1472-6963-10-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Astbury B, Leeuw FL. Unpacking black boxes: mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation 2010;31:363–81. 10.1177/1098214010371972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mukumbang FC, Van Belle S, Marchal B, et al. Exploring ’generative mechanisms' of the antiretroviral adherence club intervention using the realist approach: a scoping review of research-based antiretroviral treatment adherence theories. BMC Public Health 2017;17:385 10.1186/s12889-017-4322-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Savigny D, Adams T. A.f.H.S.a.P. Research Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arriola KR, Kennedy SS, Coltharp JC, et al. Development and implementation of the cross-site evaluation of the CDC/HRSA corrections demonstration project. AIDS Educ Prev 2002;14:107–18. 10.1521/aeap.14.4.107.23883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robillard AG, Gallito-Zaparaniuk P, Arriola KJ, et al. Partners and processes in HIV services for inmates and ex-offenders. Facilitating collaboration and service delivery. Eval Rev 2003;27:535–62. 10.1177/0193841X03255631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ginn S. Promoting health in prison. BMJ 2013;346:f2216 10.1136/bmj.f2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Woodall J. Why has the health-promoting prison concept failed to translate to the United States? Am J Health Promot. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0890117116670426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woodall J, Dixey R. Advancing the health-promoting prison: a call for global action. Glob Health Promot 2017;24:58–61. 10.1177/1757975915581760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Henostroza G, Topp SM, Hatwiinda S, et al. The high burden of tuberculosis (TB) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in a large Zambian prison: a public health alert. PLoS One 2013;8:e67338 10.1371/journal.pone.0067338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maggard KR, Hatwiinda S, Harris JB, et al. Screening for tuberculosis and testing for human immunodeficiency virus in Zambian prisons. Bull World Health Organ 2015;93:93–101. 10.2471/BLT.14.135285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reid SE, Topp SM, Turnbull ER, et al. Tuberculosis and HIV control in sub-Saharan African prisons: ’thinking outside the prison cell'. J Infect Dis 2012;205(Suppl 2):S265–73. 10.1093/infdis/jis029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD. An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review 1995;20:709–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rousseau DM, Sitkin SB, Burt RS, et al. Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review 1998;23:393–404. 10.5465/AMR.1998.926617 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McKnight DH, Cummings LL, Chervany NL. Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review 1998;23:473–90. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schaaf M, Topp SM, Ngulube M. From favours to entitlements: community voice and action and health service quality in Zambia. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:847–59. 10.1093/heapol/czx024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]