Abstract

Aims

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy remains a public health problem despite >40 years of attention. Little is known about how state policies have evolved and whether policies represent public health goals or efforts to restrict women’s reproductive rights.

Methods

Our data set includes US state policies from 1970 through 2013 obtained through original legal research and from the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA)’s Alcohol Policy Information System. Policies were classified as punitive to women or supportive of them. The association between numbers of punitive policies and supportive policies in 2013 with a measure of state restrictions on reproductive rights and Alcohol Policy Effectiveness Scores (APS) was estimated using a Pearson’s correlation.

Results

The number of states with alcohol and pregnancy policies has increased from 1 in 1974 to 43 in 2013. Through the 1980s, state policy environments were either punitive or supportive. In the 1990s, mixed punitive and supportive policy environments began to be the norm, with punitive policies added to supportive ones. No association was found between the number of supportive policies in 2013 and a measure of reproductive rights policies or the APS, nor was there an association between the number of punitive policies and the APS. The number of punitive policies was positively associated, however, with restrictions on reproductive rights.

Conclusion

Punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies are associated with efforts to restrict women’s reproductive rights rather than effective efforts to curb public health harms due to alcohol use in the general population. Future research should explore the effects of alcohol and pregnancy policies.

Short Summary

The number of states with alcohol and pregnancy policies has increased since 1970 (1 in 1974 and 43 in 2013). Alcohol and pregnancy policies are becoming increasingly punitive. These punitive policies are associated with efforts to restrict women’s reproductive rights rather than policies that effectively curb alcohol-related public health harms.

Keywords: alcohol, pregnancy, policy

Introduction

On February 2, 2016, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a report estimating the number of alcohol-exposed pregnancies in the USA (Green et al., 2016). Along with the report, the CDC issued infographics and other communications materials that appear to advise all women of reproductive age who have sex with men to avoid alcohol unless they are using contraception (CDC, 2016). These materials, while an updated version of long-term guidance cautioning against use of alcohol during pregnancy, received widespread attention and were met with significant outrage as both paternalistic and unrealistic (Cunha, 2016; Petri, 2016). To the best of our knowledge, over the past decade, there has not been similar media attention or public outrage about federal-level or state-level policy changes related to alcohol use during pregnancy. There is no question that alcohol use during pregnancy is a public health problem and that heavy alcohol use during pregnancy has a range of adverse health outcomes on the fetus, including adverse birth outcomes, fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (Russell and Skinner, 1988; Sokol et al., 2003; May et al., 2008; Strandberg-Larsen et al., 2009). Because policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy generally do not get much media or public attention and because such policies are increasing at both the federal and state levels, understanding more about state policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy is important.

Previous research has described state-level policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy and categorized them as focused on punishing pregnant women who drink alcohol during pregnancy or as supportive of pregnant women (Thomas et al., 2006; Drabble et al., 2014). Punitive policies seek to control pregnant women’s behavior by civilly committing them, mandating reporting of pregnant women who use or are suspected of using alcohol to law enforcement and/or child welfare agencies, and initiating child welfare proceedings to temporarily remove children from mothers or terminate parental rights. Supportive policies seek to provide information, early intervention, and treatment and services to pregnant women, such as laws that mandate priority treatment in substance abuse treatment programs.

There has been some previous research about these policies and trends in these policies. Thomas et al. (2006) examined factors that explained differences across states in adoption of policies pertaining to alcohol use during pregnancy from 1980 to 2003. Controlling for relevant political and socio-economic variables, the only significant predictor of whether a state adopted a supportive policy (defined in that paper as a policy furthering women’s autonomy) was the proportion of women in the state legislature. Although this finding is meaningful, it does not directly address an important question about whether policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy are intended to be effective public health policies likely to reduce harms from alcohol use during pregnancy or whether they are intended primarily to restrict women’s reproductive autonomy or rights, a key question raised by scholars (Gomez, 1997; Chavkin et al., 1998; Thomas et al., 2006).

Drabble et al. (2014) examined alcohol and pregnancy policy environments [defined as primarily punitive, primarily supportive or mixed approaches (including both punitive and supportive policies)] and found significant variation in policy environments across states. This research also found that, between 2003 and 2012, most types of policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy increased. For example, the number of states that defined alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect increased by 40%, although the number of states that gave pregnant women priority in terms of substance abuse treatment remained steady.

In this article, we extend previous research about alcohol and pregnancy policies. Using data between 1970 through 2013, we: (a) examine trends in individual types of alcohol and pregnancy policy, such as mandatory warning signs laws, laws mandating priority substance abuse treatment for pregnant women and laws requiring reporting of evidence of alcohol use and abuse during pregnancy to law enforcement or child welfare agencies; (b) examine trends over time in the number of states that have only punitive policy environments, only supportive environments, or mixed policy environments; (c) compare the state alcohol and pregnancy policy environments in 2013 to a measure of the effectiveness of the general alcohol policy environment in the states with respect to reducing alcohol-related harms, and a measure of how much a state restricts women’s reproductive rights.

Understanding these trends enhances understanding of the current alcohol and pregnancy policy environment in US states. It also will be a first step toward understanding whether existing alcohol and pregnancy policy environments conform more closely with effective public health efforts to reduce harms due to alcohol use or with efforts to restrict women’s reproductive rights.

Methods

Data come from three sources: (a) ‘Alcohol and Pregnancy Statutes and Regulations’; (b) ‘General Population Alcohol Policy Effectiveness Score (APS)’ and (c) ‘Reproductive Rights Policies Score’.

Alcohol and Pregnancy Statute and Regulations

The data for Alcohol and Pregnancy Statutes and Regulations come from original legal research and the National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA)’s Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) (NIAAA, 2016). We gathered these data in the following way: (a) we identified relevant statutes and regulations on each of six policy topics available on APIS (see Table 1); (b) identified effective dates for each one; (c) coded statutes and regulations, including ensuring inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability consisted of using a standard procedure for legal data coding: having each of two coders gather and code data from half the 51 jurisdictions and then exchanging the jurisdictions for purposes of having one coder check the work of the other. In situations in which there were questions or different coding decisions, which was a rarity, the legal researchers worked together until consensus was reached; and (d) performed further quality control on our data set by comparing our results to those available from secondary sources, primarily the The Guttmacher Institute: Substance Abuse During Pregnancy Fact Sheets (https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/substance-abuse-during-pregnancy).

Table 1.

State-level policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy

| Policy | Policy description |

|---|---|

| Mandatory warning signs | Require that notices be posted in settings, such as licensed premises, where alcoholic beverages are sold, and healthcare facilities, where pregnant women receive treatment. Policy provisions specify who must post warning signs, the specific language required on the signs, and where signs must appear. The warning language required across jurisdictions varies in detail, but in each case, warns of the risks associated with drinking during pregnancy |

| Priority treatment | These provisions mandate priority access to substance abuse treatment for pregnant and postpartum women who abuse alcohol |

| Prohibitions against criminal prosecution | These provisions prohibit use of the results of medical tests, such as prenatal screenings or toxicology tests, as evidence in the criminal prosecutions of women who may have caused harm to a fetus or a child |

| Reporting requirements | Mandated or discretionary reporting of suspicion of or evidence of alcohol use or abuse by women during pregnancy to either CPS or to a health authority. Evidence may consist of screening and/or toxicological testing of pregnant women or toxicological testing of babies after birth and reporting may be either for child abuse/neglect investigation, provision of health services or for data gathering purposes |

| Child abuse/child neglect | This topic addresses the legal significance of a woman’s conduct prior to birth of a child and of damage caused in utero and, in some cases, define alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse or neglect |

| Civil commitment | Mandatory involuntary commitment of a pregnant woman to treatment or mandatory involuntary placement of a pregnant woman in protective custody of the state for the protection of a fetus from prenatal exposure to alcohol. |

Information about state-level policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy has been tracked in APIS back to 2003 for four policy topics (priority treatment, legal significance for child abuse/child neglect, reporting requirements and mandatory warning signs), and back to 1998 for the other two (civil commitment and prohibitions against criminal prosecution [defined below]). Data about policies and effective dates from 2003 to 2013 and, when available, 1998–2013 were obtained directly from APIS. For policies where effective date information was not available in APIS (that is, prior to either 2003 or 1998, depending on policy topic), we conducted original legal research on statutes and regulations using online legal research databases Westlaw and HeinOnline (www.westlaw.com, http://home.heinonline.org/). If definitive information was not available through either of those two databases, we consulted with officials in state governments. We also used the Bill Effective Dates resource, developed by StateScape (http://www.statescape.com/resources/legislative/bill-effective-dates.aspx), to assist in precise identification of effective dates of relevant statutes wherein an effective date is listed as, for example, ‘90 days after signature by Governor’. Finally, we assessed whether any additional statutes and regulations relevant to our interests were enacted prior to data in APIS and included those as fully as effective date data were available.

Once statutory and regulatory data and effective dates were obtained and assessed, policies were coded by a two person legal research team (2nd and 3rd authors), who have been trained in and have extensive experience coding legal data for social science purposes. Finally, we created a codebook for each policy and variable and updated it as necessary to ensure that it reflected any changes in definitions, coding conventions and procedures that occurred during the research process (Tremper et al., 2010a,b).

Specific alcohol and pregnancy policy variables in our data set include the following [see Table 1]: ‘Mandatory warning signs’ includes requirements for establishments that sell alcohol to be consumed either on- or off-premise to post signs warning about the dangers of drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Priority treatment is divided into two: the first is ‘Priority treatment for pregnant women’, which includes policies that give pregnant women (but not women with children) priority for entering substance abuse treatment programs; the second is ‘Priority treatment for pregnant women and women with children’, which includes policies that give pregnant women and women with children priority for entering treatment. The variable does not distinguish whether the priority is given for outpatient or inpatient settings or publicly or privately funded sites. ‘Prohibitions on criminal prosecution’ includes policies that prohibit use of the results of medical tests, such as evidence from prenatal screening or toxicology tests, in criminal prosecutions of women who may have harmed a fetus or child. ‘Civil commitment’ includes policies that allow for mandatory involuntary commitment to treatment or the care of the state to prevent harm to a child due to a pregnant woman’s alcohol use. Per recent research (Drabble et al., 2014), reporting requirements is divided into two: ‘Reporting requirements for Child Protective Services (CPS) purposes’ includes mandatory or discretionary reporting to CPS for purposes of assessing risk of child abuse/neglect and ‘Reporting requirements for data and treatment purposes’ includes mandatory or discretionary reporting for purposes of data collection/surveillance or assessing need for substance abuse treatment. The ‘Child Abuse/Neglect’ policy includes states that have adopted statutes and/or regulations that clarify the rules for evidence of prenatal alcohol exposure in child welfare proceedings, such as those alleging child abuse, child neglect, child deprivation or child dependence, or concerning termination of parental rights. Each alcohol and pregnancy policy variable is dichotomous, coded as 0 if it was not in effect and 1 if it was in effect for that state that year.

Scholars have divided responses to substance use during pregnancy into supportive versus punitive or those that are supportive versus those that restrict women’s autonomy (Gomez, 1997; Chavkin et al., 1998; Drabble et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2006). Following our approach in a previously published analysis (Drabble et al., 2014), we created a four category categorical variable characterizing policy environments for each state and year as ‘supportive only’ (one or more of warning signs, priority treatment, reporting requirements for data or treatment purpose, and limitations on criminal prosecution and no punitive policies), ‘punitive only’ (one or more of civil commitment, reporting requirements for CPS purposes, and child abuse/neglect and no supportive policies), ‘mixed supportive and punitive’ (one or more supportive and one or more punitive policies), and ‘no policy’.

To avoid problems of multiple comparisons, for the comparison with the General Population APS and Reproductive Rights scores, we created punitive and supportive environment scales. ‘Number of punitive policies’ is the sum of each punitive policy in effect in that state for that year (could range from 0 to 3). ‘Number of supportive policies’ is the sum of each supportive policy in effect in that state for that year (could range from 0 to 5).

‘General Population APS’ is a composite score that characterizes the efficacy of the overall alcohol policy environment in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. (Nelson et al., 2013), and is based on alcohol policy and alcohol consumption data from 2000 to 2010 (Naimi et al., 2014). To create the APS, a modified Delphi process was used consisting of 10 alcohol policy experts. The policy experts performed three tasks: (a) nominating and selecting existing alcohol policies; (b) rating the relative efficacy of those policies and (c) developing implementation ratings for each policy. Forty-seven alcohol control policies were initially nominated by panelists as effectively reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms at the population level (Nelson et al., 2013). Prior to rating, investigators developed standardized descriptions of each policy. Panelists then independently rated the efficacy of each policy. Several methods were used to aggregate policy data into APS scores for each state-year. Ultimately, scores were divided by their respective maximum possible scores and multiplied by 100 to rescale them within a theoretical range from 0 to 100 (Naimi et al., 2014). The 2013 APS data that are used in our analysis come from a personal communication with the scale’s creator (personal communication with Timothy Naimi, 7 December 2016).

‘Reproductive Rights Policies Score’ is the number of 14 possible laws per state restricting abortion that had been signed into law in 2013. The data for the number of these laws in effect in each state in 2013 come from a report published by the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health (Burns et al., 2014). This number includes all laws on the books in 2013, including those in effect and those on hold while court cases against them continue. Included laws and restrictions are mandatory parental involvement before a minor obtains an abortion; mandatory waiting periods before a woman can obtain an abortion; requirements to have or be offered an ultrasound prior to having an abortion; restrictions on abortion coverage in: private health insurance; in Medicaid; in public employee health insurance plans; mandating that clinicians that provide abortion are licensed physicians; have hospital admitting privileges; requiring abortion facilities to conform to standards of Ambulatory Surgery Centers; refusal to perform abortion services allowed; restrictions on provision of medication abortion; below average number of abortion providers per women of reproductive age; and gestational limit for abortion set by law.

Analysis

Data analysis is primarily descriptive and includes graphical plotting of alcohol and pregnancy policy trends over time, estimation of how Alcohol and Pregnancy Policy environments change (e.g. a state could move from no laws to punitive or punitive to supportive or supportive to mixed), and Pearson’s correlations of associations among policy climates in 2013. For all analyses except for the examination of associations between policy climates, we used Alcohol and Pregnancy policy data from 1970 to 2013.

Results

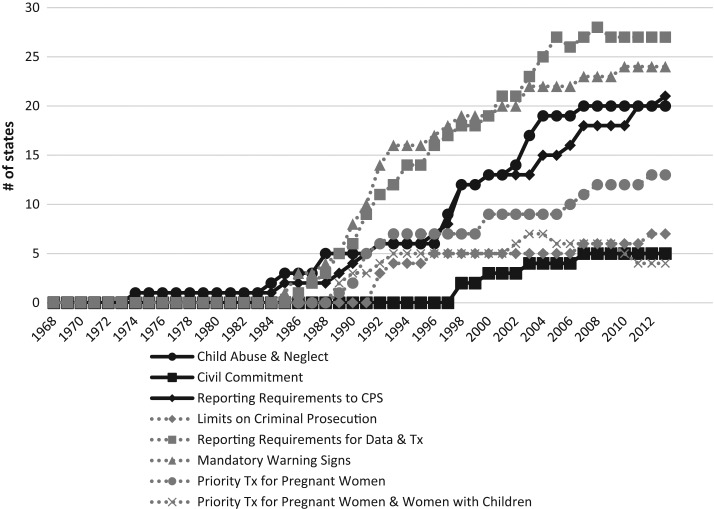

Overall, the number of states with at least one Alcohol and Pregnancy policy has increased dramatically since 1970. In 1970, no state had an Alcohol and Pregnancy policy; in 1980, 1 state (Massachusetts) had an Alcohol and Pregnancy policy; in 1990, 20 states had at least one policy; in 2000, 38 states had at least one policy; and in 2010 (through 2013), 43 states had at least one alcohol and pregnancy policy [see Figure 1].

Fig. 1.

Alcohol and Pregnancy Policies by year.

The first Alcohol and Pregnancy policy took effect in Massachusetts in 1974 (‘Reporting for CPS purposes and Child Abuse/Neglect’); no other state had a policy go into effect until 1984 (Rhode Island with ‘Child Abuse/Neglect’). The first supportive policy went into effect in 1984 (Washington, DC with ‘Mandatory Warning Signs’).

In 2013, the most common Alcohol and Pregnancy policies were both supportive: ‘Reporting for data or treatment purposes’ (in 27 states) and Mandatory Warning signs (in 24 states). The least common policy was also supportive: ‘Priority Treatment for both pregnant women and women with children’ (in 4 states), although 13 states mandated ‘Priority Treatment for pregnant women only’. Also in 2013, the most common punitive policy was ‘Reporting for CPS purposes’ (21 states), and the least common punitive policy was ‘Civil Commitment’ (5 states) [See Figure 1].

All policy types have increased over time. The only policy type that has decreased since 2000 is ‘Priority Treatment for both pregnant women and women with children’ (from a peak of seven states in 2003–2004 to four in 2013). Across all policies, there was minimal policy activity in the 1980s, a dramatic increase in policy activity in the 1990s and early 2000s, and a flattening out in the number of new policies beginning in the mid-2000s.

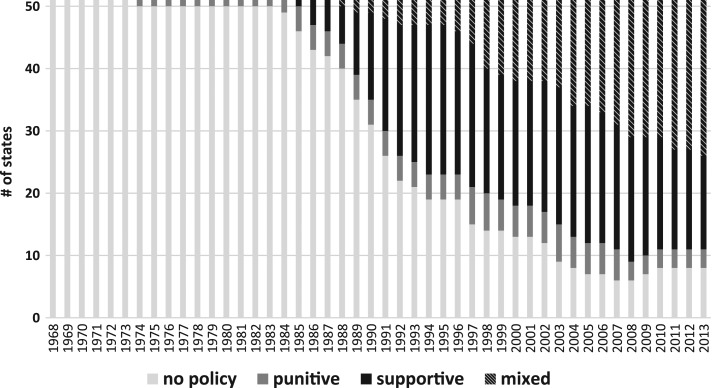

Trends in Alcohol and Pregnancy Policy Environment

In the 1970s and early to mid-1980s, Alcohol and Pregnancy Policy Environments were either punitive or supportive. The first state transitioned to a mixed alcohol and pregnancy policy environment in 1988 [See Figure 2]. Since 1985, the number of states with punitive alcohol and pregnancy environments remained steady (between four and six), while the number of states with a supportive alcohol and pregnancy environment increased dramatically between 1985 and 1995 (one to 24), and then steadily decreased to 15 in 2013. The number of states with a mixed alcohol and pregnancy policy environment has increased steadily over time, from 1 in 1988 to 25 in 2013 [See Figure 2]. As of 2013, half of states (25) had a mixed environment, 29% (15) had a supportive environment, 6% (3) had a punitive environment and 16% (8) had no policy.

Fig. 2.

Punitive, Supportive, and Mixed Alcohol and Pregnancy Policy Environments over time.

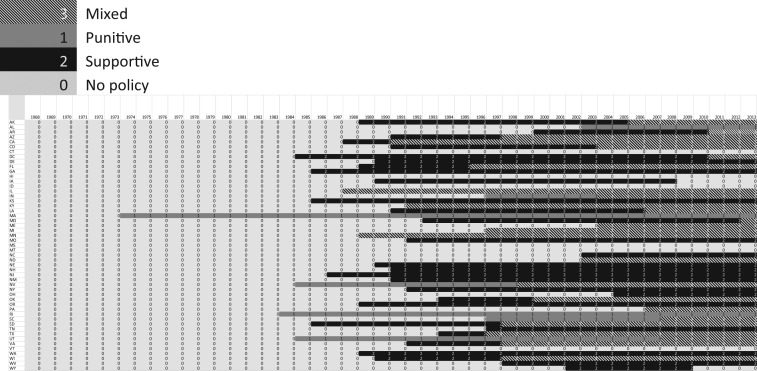

The changes in the alcohol and pregnancy policy environment have occurred both across states and over time [See Figure 3]. The two most common transitional patterns were moving from no alcohol and pregnancy policy to supportive alcohol and pregnancy policy environments (29%; 15 states), and moving from no policy to supportive to mixed alcohol and pregnancy policy environments (27%; 14 states). Twelve percent (6 states) had no alcohol and pregnancy policy in place for the entire time from 1970 to 2013. Of the 25 states that had a mixed alcohol and pregnancy policy environment in 2013, more than half became mixed after being supportive (56% or 14 states), about one-fourth became mixed directly from no policy (24% or 6 states), and one-fifth became mixed after being punitive (20% or 5 states). These transitions to mixed policy environments are primarily in the direction of becoming more punitive.

Fig. 3.

Punitive, Supportive, and Mixed Alcohol and Pregnancy Policy Environments by State over time.

Reflection of General Alcohol Policy Effectiveness or Reproductive Rights

The mean General Population APS in 2013 was 43.2 (SD 8.1) and the mean Reproductive Rights score in 2013 was 8.1 (SD 4.5). The number of supportive alcohol and pregnancy policies was not associated with the number of punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies, the General Population APS, or Reproductive Rights Score [See Table 2]. The number of punitive policies also was not associated with the General Population APS. The number of punitive policies was positively associated with Reproductive Rights Score: states with more punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies had more restrictive reproductive rights policies.

Table 2.

Pairwise Pearson’s correlations of the association between Alcohol and Pregnancy Policy Environments, General Population APS, and Reproductive Rights Score

| # Of punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies | # Of supportive alcohol and pregnancy policies | General Population APS | Reproductive rights score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Of punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies | 1.00 | |||

| # Of supportive alcohol and pregnancy policies | 0.141 | 1.00 | ||

| P = 0.325 | ||||

| General Population APS | −0.060 | −0.086 | 1.00 | |

| P = 0.678 | P = 0.549 | |||

| Reproductive Rights Score | 0.383 | 0.044 | 0.045 | 1.00 |

| P = 0.006 | P = 0.762 | P = 0.752 |

Discussion

Our study has three key findings. First, the number of states with one or more alcohol and pregnancy policies has increased dramatically since 1970. There was minimal alcohol and pregnancy policy activity in the 1970s and 1980s, but there was a dramatic increase in the 1990s and early 2000s. The most adopted supportive alcohol and pregnancy policies between 1970 and 2013 require reporting alcohol use during pregnancy for the purposes of aggregated data collection and/or treatment for women. On the punitive side, the most adopted alcohol and pregnancy policies have been reporting requirements to CPS and defining alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect. The smallest increases from 1970 to 2013 were for the supportive policy of priority treatment for pregnant women (or pregnant women and women with children) and the punitive policy of civil commitment. The emphasis on reporting policies (that typically go into effect after a woman has given birth) rather than policies to care for or treat women during pregnancy (whether through supporting them by giving them priority for treatment or punishing them through civil commitment) is striking.

Second, alcohol and pregnancy policy environments are becoming increasingly punitive. These alcohol and pregnancy policy environments were initially punitive and then began to become supportive in the 1980s and 1990s before becoming mixed in the 2000s and beyond. The key longitudinal pattern is that alcohol and pregnancy policy environments have become mixed primarily through states with supportive alcohol and pregnancy policies adding one or more punitive policies. This trend is worrying because research related to drug use during pregnancy suggests punitive policies lead women to avoid and delay entering prenatal care and substance abuse treatment (Jessup et al., 2003; Roberts and Pies, 2011) and are disproportionally applied to Black women (Paltrow & Flavin, 2013; Roberts et al., 2014). If punitive policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy function similarly to punitive policies related to drug use during pregnancy in leading to delays in entering treatment, the increase in punitive policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy may be particularly concerning, as research suggests that women needing treatment for alcohol use disorders face more barriers than men in accessing treatment (Alvanzo et al., 2014; Verissimo and Grella, 2017) and that delays in accessing treatment remains an impediment to successful treatment completion among pregnant women (Albrecht et al., 2011).

Third, punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies are associated with policies that restrict women’s reproductive autonomy rather than general alcohol policy environments that effectively reduce harms due to alcohol use among the general population. This finding suggests that a primary goal of pursuing such policies appears to be restricting women’s reproductive rights rather than improving public health. This finding will likely be of concern to groups and individuals who care about women’s reproductive rights. The finding that punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies reflect efforts to restrict women’s reproductive autonomy rather than efforts to have policies effective at reducing alcohol-related harms should also be of concern to groups and individuals who care about reducing harms due to alcohol use during pregnancy. There is no question that alcohol use during pregnancy is a public health problem. It is thus reasonable to expect that organizations concerned with reducing harms due to alcohol use during pregnancy should also be concerned that policies that address this topic may be unnecessarily restricting women’s reproductive rights in the name of public health without evidence that they effectively address the underlying public health problem.

There are some limitations to note. First, we used secondary sources for our measures of general alcohol policy effectiveness and reproductive rights. Although the General Population APS was designed for research purposes, the reproductive rights score was not. Second, although alcohol and pregnancy policies have been in place in US states since the 1970s, we only have 1 year of data for our comparison measures. It is possible that the association between punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies and reproductive rights policies has not always existed. It is also possible that, in earlier eras, alcohol and pregnancy policies were more in line with generally effective alcohol policies. Third, we interpret our findings of the association between punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies and reproductive rights policies and the lack of association of any alcohol and pregnancy policy with generally effective alcohol policies as conveying something about intent behind the policies. However, we do not have data about whether policymakers viewed these policies as a way to restrict women’s reproductive rights or whether policymakers had knowledge of which general alcohol policies were effective. Determining whether the alcohol and pregnancy policies are effective at reducing harms due to alcohol use during pregnancy would require analyses of the impact of these policies on alcohol use during pregnancy and birth outcomes, a strategy in which we are engaged.

This study also has strengths. First, this study used rigorous legal research methods for coding alcohol and pregnancy policies. Second, this study extends previous research on trends in alcohol and pregnancy policies before 1980 and after 2012, time periods not included in previous research. Third, while scholars and advocates have debated whether alcohol and pregnancy policies reflect true public health efforts to reduce harms due to alcohol use during pregnancy or whether they are attempts to restrict women’s reproductive rights, this is the first study of which we are aware that directly assesses the relationship between alcohol and pregnancy policies and other policies.

In conclusion, state policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy have increased over time and have become more punitive. Punitive alcohol and pregnancy policies are associated with efforts to restrict women’s reproductive rights. To understand the impact of these policies, future research should explore the effects of policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy on alcohol use during pregnancy and birth outcomes. Rather than devoting attention to updated CDC communications materials, journalists and advocates concerned with government responses to alcohol use during pregnancy should focus their attention on activities of US states.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anna Bernstein and Beckie Kriz, RN, MSc, for project support; and Tim Naimi, MD, MPH for sharing 2013 Alcohol Policy Effectiveness scores.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01AA023267]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

References

- Albrecht J, Lindsay B, Terplan M (2011) Effect of waiting time on substance abuse treatment completion in pregnant women. J Subst Abuse Treat 41:71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvanzo AA, Storr CL, Mojtabai R, et al. (2014) Gender and race/ethnicity differences for initiation of alcohol-related service use among persons with alcohol dependence. J Alcohol Drug 140:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns B, Dennis A, Douglas-Durham E (2014) Evaluating priorities: Measuring women’s and children’s health and well-being against abortion restrictions in the states. Research report: Ibis Reproductive Health.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) More than 3 million US women at risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p0202-alcohol-exposed-pregnancy.html (29 March 2017, date last accessed).

- Chavkin W, Wise PH, Elman D (1998) Policies towards pregnancy and addiction. Sticks without carrots. Ann N Y Acad Sci 846:335–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha D. (2016) The CDC’s alcohol warning shames and discriminates against women. Time Magazine, New York, NY. http://time.com/4209491/cdc-alcohol-pregnancy/ (25 January 2017, date last accessed).

- Drabble LA, Thomas S, O’Connor L, et al. (2014) State responses to alcohol use and pregnancy: findings from the Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS). J Soc Work Pract Addict 14:191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez LE. (1997) Misconceiving Mothers: Legislators, Prosecutors, and the Politics of Prenatal Drug Exposure. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green PP, McKnight-Eily LR, Tan CH, et al. (2016) Vital Signs: Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies--United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup M, Humphreys JC, Brindis C, et al. (2003) Extrinsic barriers to substance abuse treatment among pregnant drug dependent women. J Drug Issues 33:285–304. [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, et al. (2008) Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome in South Africa: a third study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32:738–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, et al. (2014) A new scale of the U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. Am J Prev Med 46:10–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Xuan Z, Babor TF, et al. (2013) Efficacy and the strength of evidence of U.S. alcohol control policies. Am J Prev Med 45:19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2016) Alcohol Policy Information System. Bethesda, MD. http://www.alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/ (25 January 2017, date last accessed).

- Paltrow LM, Flavin J (2013) Arrests of and forced interventions on pregnant women in the United States, 1973–2005: implications for women’s legal status and public health. J Health Polit Policy Law 38:299–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri A. (2016) The CDC’s incredibly condescending warning to young women. Washington Post, Washington D.C. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/compost/wp/2016/02/03/the-cdcs-incredibly-condescending-warning-to-young-women/?utm_term=.fc2acf7e9efb (25 January 2017, date last accessed).

- Roberts SC, Pies C (2011) Complex calculations: How drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Matern Child Health J 15:333–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SC, Zahnd E, Sufrin C, et al. (2014) Does adopting a prenatal substance use protocol reduce racial disparities in CPS reporting related to maternal drug use? A California case study. J Perinatol 35:146–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M, Skinner JB (1988) Early measures of maternal alcohol misuse as predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 12:824–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, Nordstrom B (2003) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA 290:2996–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg-Larsen K, Gronboek M, Andersen AM, et al. (2009) Alcohol drinking pattern during pregnancy and risk of infant mortality. Epidemiology 20:884–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Rickert L, Cannon C (2006) The meaning, status, and future of reproductive autonomy: the case of alcohol use during pregnancy. UCLA Women’s Law J 15:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC (2010. a) Measuring law for evaluation research. Eval Rev 34:242–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremper C, Thomas S, Wagenaar AC (2010. b) Measuring Law for Public Health Research. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Verissimo ADO, Grella CE (2017) Influence of gender and race/ethnicity on perceived barriers to help-seeking for alcohol or drug problems. J Subst Abuse Treat 75:54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]