Abstract

Background

older adults are frequent users of primary healthcare services, but are at increased risk of healthcare-related harm in this setting.

Objectives

to describe the factors associated with actual or potential harm to patients aged 65 years and older, treated in primary care, to identify action to produce safer care.

Design and Setting

a cross-sectional mixed-methods analysis of a national (England and Wales) database of patient safety incident reports from 2005 to 2013.

Subjects

1,591 primary care patient safety incident reports regarding patients aged 65 years and older.

Methods

we developed a classification system for the analysis of patient safety incident reports to describe: the incident and preceding chain of incidents; other contributory factors; and patient harm outcome. We combined findings from exploratory descriptive and thematic analyses to identify key sources of unsafe care.

Results

the main sources of unsafe care in our weighted sample were due to: medication-related incidents e.g. prescribing, dispensing and administering (n = 486, 31%; 15% serious patient harm); communication-related incidents e.g. incomplete or non-transfer of information across care boundaries (n = 390, 25%; 12% serious patient harm); and clinical decision-making incidents which led to the most serious patient harm outcomes (n = 203, 13%; 41% serious patient harm).

Conclusion

priority areas for further research to determine the burden and preventability of unsafe primary care for older adults, include: the timely electronic tools for prescribing, dispensing and administering medication in the community; electronic transfer of information between healthcare settings; and, better clinical decision-making support and guidance.

Keywords: patient safety, quality improvement, older adults, primary care

Introduction

Older adults are frequent users of primary healthcare services and account for half of all 340 million general practice consultations in the UK each year [1]. Considering 2–3% of all primary care encounters result in a patient safety incident, with 1 in 25 causing a serious harm outcome [2], 170,000 older adults each year in the UK may receive care that causes death or severe adverse, physical or psychological outcomes. The true frequency and burden of primary healthcare-related harm to older adults is unknown although several studies suggest they are at increased risk [3–5].

Estimates of the frequency of unsafe care in hospitals assess the risk as twice as high for older adults compared to younger age groups [6, 7]. No comparable work on this scale has provided estimates of the frequency and nature of such harm in primary care. Studies have examined patient safety using different research methods, for example, analysing routinely collected data (such as adverse drug reactions) for prescribing errors [3] or case note reviews [4]. Trigger tool studies (searching clinical records for relevant outcomes) have suggested that older adults are at increased risk of diagnostic and medication-related incidents [5].

Despite recognised limitations of incident reporting, including under-reporting, selection bias and incomplete causation, incident reports can provide an important lens for understanding unsafe care, in terms of what happened and perceived causes. Given the paucity of existing primary care safety literature, a structured process for identifying priorities for improvement from incident reports was needed. The value of our method has been shown in studies of systemic causes of safety-related hospital deaths [8], and to identify the scope for practice improvement in primary care for vulnerable children [9, 10].

The safety of primary care is an emerging global priority for healthcare, led by the World Health Organization (WHO) [11]. This is mirrored in UK policy [12], where there is recognition that vulnerable groups, like older adults, should have priority attention. Given this global interest [13], and the complexity of delivering healthcare to an ageing population [14], it is important to create a better understanding of the healthcare-related harm experienced by older adults.

Methods

We carried out a cross-sectional, mixed-methods study of a patient safety incident database with a sample of reports selected for analysis, known to involve patients 65 years of age and older. This combined a detailed data coding process and iterative generation of data summaries using descriptive statistical and thematic analysis methods [9].

Data source

Primary data were extracted from the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS). This is a database of over 14 million patient safety incident reports from healthcare organisations in England and Wales. A patient safety incident is defined as, ‘any unintended or unexpected incident that could have harmed or did harm a patient during healthcare delivery’ [15]. Reporting began voluntarily in 2003 but, since 2010, it has been mandatory to report any incident that resulted in severe patient harm or death. Since the inception of the NRLS, reporting arrangements have included batch returns via local risk management systems, and more recently in England by direct notification to the Care Quality Commission (an independent regulator of all health and social care services in England) as well as direct reporting to the NRLS. Reports contained structured information about location, patient demographics and the reporter's perception of harm severity, complemented by unstructured free-text descriptions of the incident, potential contributory factors and planned actions to prevent reoccurrence. The database was described in more detail in a study of patient safety-related hospital deaths in England [8].

Study population

We have undertaken a sub-analysis of all reports describing the care of older adults from a larger agenda setting study for general practice to characterise 13,699 reports [9]. The period chosen for the study was 1 April 2005–30 September 2013, which was the largest cross section of data available at the outset of our study. In this time, there were 42,729 reports about incidents occurring in general practice. The study population was assembled by combining all incident reports throughout the study period that resulted in severe harm or death (n = 1,199) with a weighted random sample of incident reports from 2012 onwards with preference for more recent and more harmful incidents (no harm n = 6,691, low harm n = 3,461, moderate harm n = 2,348); described in detail in our protocol paper [9]. Within the resulting total of 13,699 incident reports, 6,472 (47%) specified the age of the patient, of which 3,417 (53%) involved patients aged 65 years and older. Reports were excluded (n = 1,826) if there was insufficient clinical information (n = 1,417) or because on detailed scrutiny the incident had not occurred in primary care (n = 409). The majority of reports with insufficient clinical information described pressure ulcers (n = 1,235). Whilst pressure ulcers can represent the outcome of poor care, such reports contained little descriptive or contextual information (e.g. simply ‘Pressure ulcer, Grade 3’). Other reports were excluded if, by the NRLS definition, no patient safety incident had occurred (n = 182). The resulting final study population was 1,591 incident reports.

Data coding

A small team made up of general practitioners, nurses and health services researchers was trained in root cause analysis and human factors in healthcare [9]. This team then reviewed the free-text component of each incident report and coded the information in relation to: the primary patient safety incident that was reported to have directly affected patient care (e.g. prescribing incident) and the chain of incidents leading up to the safety incident (e.g. miscommunication between staff); the contributory factors (e.g. staff knowledge) and reported patient harm outcomes with harm severity classified from the free-text report according to WHO International Classification for Patient Safety definitions [16]. A random sample of 20% of the reports was double-coded. All discordance between coders were discussed to ensure correct interpretation of codes and their definitions. Difficult cases were discussed at weekly team meetings and a third, senior investigator (A.C.S.), arbitrated. The process has previously been described in more detail [9].

Data analyses

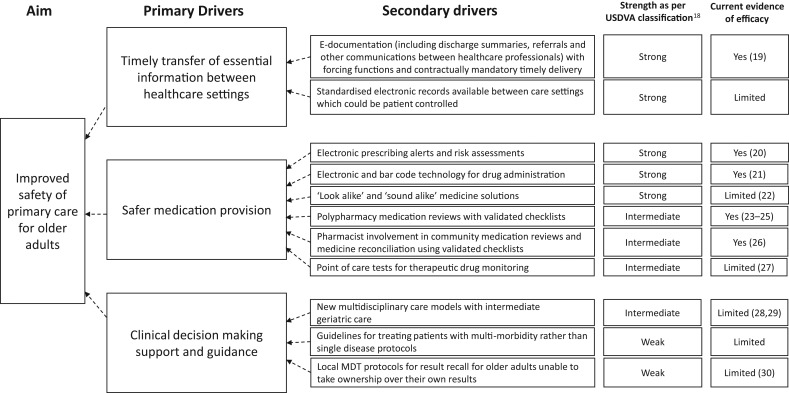

We undertook an exploratory descriptive analysis to assess the most frequent and most harmful primary incident types in the sample, the associated chain of incidents, and other contributory factors. We used thematic analysis to identify and describe recurring themes (not captured by the quantitative data) that could be targeted to mitigate future similar incidents. The most commonly identified causes and potential interventions, suggested by the reporter or the experience of the team, were summarised in a driver diagram. This is a quality improvement tool that has previously been used by our team to summarise priority areas for change and mapping potential interventions [17]. We also carried out literature searches to determine whether existing interventions or initiatives for promoting patient safety had been described in each area. When available, the strength of each intervention was graded using the US Department of Veterans Affairs classification, where the strongest designs are permanent and physical rather than temporary and procedural [18].

Ethical approval

Aneurin Bevan (Gwent, Wales, UK) University Health Board's Research Risk Review Committee judged the study as using anonymised data for service improvement purposes and approved it on this basis (ABHB R&D Ref number: SA/410/13).

Results

Just over half of the incident reports included in our weighted sample described patient harm (n = 921/1,591, 58%). In 270 (17%) reports, this was described as a serious harm resulting in hospital admission, permanent injury or death (Table 1). The three main sources of harm were due to: medication-related incidents (e.g. prescribing, dispensing and administering; n = 486, 31%; 15% serious patient harm); communication-related incidents (e.g. incomplete or non-transfer of information across care boundaries; n = 390, 25%; 12% serious patient harm) and clinical decision-making incidents which led to the most serious patient harm outcomes (n = 203, 13%; 41% serious patient harm) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

The nature of primary care patient safety incidents occurring in a weighted sample of 3,417 older adults from the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) associated with severity of patient harm outcomes

| Incident type (examples shown in Table 2) | Harm (as described in the free-text) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious harm n (% of incident type) |

Low harm n (% of incident type) |

No harm n (% of incident type) |

Harm not specified n (% of incident type) |

Total n (% of total reports) | |

| Medication provision | 71 (15%) | 178 (36%) | 76 (16%) | 161 (33%) | 486 (31%) |

| Prescribing (1, 5) | 16 | 57 | 26 | 81 | 180 |

| Administering (2) | 12 | 56 | 29 | 29 | 126 |

| Dispensing (3) | 11 | 22 | 13 | 37 | 83 |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring (4) | 9 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 34 |

| Adverse drug reaction | 22 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 36 |

| Immunisation | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Other | 0 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 16 |

| Communication processes | 47 (12%) | 152 (39%) | 77 (20%) | 114 (29%) | 390 (25%) |

| Referral (6, 7) | 22 | 87 | 35 | 37 | 181 |

| Transfer of patient information (8–10) | 25 | 65 | 42 | 77 | 209 |

| Clinical decision-making | 83 (41%) | 72 (35%) | 17 (8%) | 31 (15%) | 203 (13%) |

| Treatment provision (11–13) | 28 | 48 | 12 | 17 | 105 |

| Assessment (14) | 55 | 24 | 5 | 14 | 98 |

| Investigative processes (11–13) | 13 (8%) | 71 (41%) | 9 (5%) | 79 (46%) | 172 (10%) |

| Equipment provision (15) | 18 (14%) | 79 (63%) | 12 (10%) | 17 (13%) | 126 (8%) |

| Access to healthcare provider (16) | 17 (17%) | 62 (63%) | 8 (8%) | 12 (12%) | 99 (6%) |

| Other | 21 (18%) | 37 (32%) | 14 (12%) | 43 (37%) | 115 (7%) |

| Total n (% of total reports) | 270 (17%) | 651 (41%) | 213 (13%) | 457 (29%) | 1,591 |

Key: serious harm as per the WHO definition resulted in hospital admission, permanent injury or death, WHO [16].

Table 2.

Examples of incident types with patient harm outcome

| Incident extract examples, minor edits made for clarity | Severity [16] |

|---|---|

| Medication provision | |

| 1. ‘Patient was prescribed penicillin and was allergic to it. Computer did not flash up allergic reaction when it was prescribed. System failed. Patient had an allergic reaction to drug.’ | Moderate |

| 2. ‘Insulin-dependent diabetic with dementia discharged following admission for hypoglycaemic episode. DN requested to monitor blood sugar/insulin. Dose of insulin on transfer of care letter different to dose on discharge summary given to patient. Also metformin stopped and patient/husband not informed so had been given. Ward contacted to verify correct regime.’ | Unknown |

| 3. ‘Patient has levothyroxine 100 mcg on repeat prescribing. Levothyroxine 25 mcg dispensed incorrectly on [date]. Patient attended surgery [three months later]—symptomatic’ | Low |

| 4. ‘Patient discharged on anticoagulant therapy warfarin 4 mg once daily—previously on 1 mg prior to admission. No INR done after discharge. Bruising, haematoma right thigh & looking very pale. Readmitted to hospital and died.’ | Death |

| 5. ‘Patient was given prescription for amoxicillin. Daughter telephoned the surgery to ask why her mother had been prescribed a medication that she was allergic to. She also wanted to make the practice aware of this fact.’ | No harm |

| Communication processes | |

| 6. ‘The patient was suffering from AF. The GP visited the patient, prescribed warfarin and documented in the notes that the patient should be referred to the DN to be monitored. The documentation in the notes failed to be communicated which meant that the patient was not monitored for 3 weeks. The patient became ill and was admitted to hospital. Subsequently the patient died.’ | Death |

| 7. ‘Urgent cancer referral fax to hospital. Received receipt with message saying, ‘Consultant has own fax machine and number in his room—Please use it in the future.’ This goes against telephone numbers issued from LHB.’ | Unknown |

| 8. ‘Housebound patient seen in Outpatients. Neighbour came to GP surgery saying medication had been altered but no notification of this to GP. Phoned Consultants Secretary who stated his letters are one month behind and she has been told by ‘the management’ that letters must be sent out in strict date order and she cannot help. GP has had to do prescription based on information given by neighbour.’ | Unknown |

| 9. ‘Recent admission, new medications added. Medication list on discharge letter did not include some of the patient's previous regular medications so GP assumed they had been discontinued by hospital. 1 month later, patient had CVA. Very hypertensive on admission. Subsequently discovered that hospital had intended her to continue antihypertensive medication, even though omitted from discharge medication list.’ | Severe |

| 10. ‘Poor interim discharge notification for patient. Inpatient [for one month] but no diagnosis etc…’ | Unknown |

| Clinical decision-making and investigative processes | |

| 11. ‘Blood test from GP was abnormal. Advice was given on test report to perform other important tests to evaluate/confirm diagnosis of myeloma. Three months later the patient presented in established renal failure. Diagnosis of myeloma made on day of admission. Patient died on ITU 4 days later. This death was totally avoidable.’ | Death |

| 12. ‘Elderly male patient 80 yrs old attended surgery with recent but not current chest pain. Given ECG which was mis-read. Patient advised to return home but should have been sent to hospital urgently. Patient died at home from heart attack within 24–48 hrs.’ | Death |

| 13. ‘Patient blood test showed Hb 8.1, sudden drop. Result seen by colleague and signed “to keep appointment in 2 weeks” At appointment blood result NOT discussed. 5 weeks after blood test patient returned short of breath and symptomatic. Required immediate treatment and urgent referral.’ | Severe |

| 14. ‘A working diagnosis of diverticulitis was made at home visit and treatment prescribed. Patient was admitted to hospital and died from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.’ | Death |

| Equipment provision | |

| 15. ‘Profiling bed and air flow mattress were ordered for same day delivery. Didn't arrive for 3 days. By this time the vulnerable patient had developed pressure sores on several parts of her body and the skin was broken on her hip requiring a dressing.’ | Moderate |

| Access to healthcare provider | |

| 16. ‘GP home visit requested for terminally ill patient at 20:30 pm. Dr. did not visit until 01:40 am. Patient died at 02:30 hrs’ | Unknown |

Key: DN, district nurse; OD, once daily; INR, international normalised ratio; AF, atrial fibrillation; LHB, local health board; GP, general practitioner; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; ITU, intensive care unit; Hb, Haemoglobin.

Medication-related incidents

One-third of reports in our weighted sample involved medication incidents (n = 486, 31%). This was mainly due to: prescribing errors involving the wrong drug or dosage (n = 180/486, 37%; Table 2, Example 1); administering medication at the wrong dose or time (n = 126/486, 26%; Table 2, Example 2) and dispensing errors including the wrong drug or wrong strength dispensed (n = 83/486, 17%; Table 2, Example 3). Other incidents included failure of drug monitoring processes (e.g. warfarin; Table 2, Example 4).

A fifth of the reports in our sample described a communication-related incident in the preceding chain of events (n = 88/486, 18%), often involving incomplete or delayed transfer of written information across care boundaries. Independent contributory factors were identified at: the staff level such as mistakes between ‘look-alike’ and ‘sound-alike’ drugs (n = 122/274, 45%); the system level such as protocols for drug dispensing (n = 87/274, 32%); and at the patient level such as multi-morbidity (n = 65/274, 23%). Some reports described how incidents were mitigated by an advocate (Table 2, Example 5).

Communication-related incidents

A quarter of reports in our weighted sample (n = 390, 25%) described a communication-related incident as the incident that led to direct harm. These were largely due to: the referral process within the multidisciplinary team and across healthcare boundaries (n = 181/390, 46%); and delays or failures to transfer essential information about the patient between healthcare settings (n = 209/390, 54%).

A missed or delayed referral by the healthcare professional was the most common referral process incident in our sample (n = 86/181, 48%; Table 2, Example 6), whilst other reports mentioned referrals sent to the wrong service or lacking key information (n = 45/181, 24%). Administrative level referral incidents were also described including referrals being sent to the wrong place (n = 50/181, 28%; Table 2, Example 7). Key information regarding diagnoses or medication changes was often missing in communication following inpatient admissions or outpatient consultations which in some incidents led to severe patient harm (Table 2, Examples 8–10).

Over half the identified contributory factors in our sample were at the system level, such as the use of fax machines and handwritten communication (n = 116/221, 52%). Staff factors such as forgetting to make the referral accounted for over a quarter (n = 61/221, 28%), whilst patient factors such as lack of knowledge of the treatment plan were responsible for a further fifth (n = 44/221, 20%).

Clinical decision-making incidents

Whilst only 13% (n = 203) of reports in our weighted sample contained clinical decision-making incidents, a larger proportion of these (n = 83/203, 41%) led to serious patient harm compared with other incident types (n = 187/1,388, 13%). The reports described assessment errors (n = 98/203, 48%) and inappropriate treatment decisions (n = 105/203, 52%). A misdiagnosis was described in 59/203 (29%) reports, including 21 reports describing a delayed cancer diagnosis.

As with the medication incidents, a fifth of the reports in our sample described a communication incident in the preceding chain of events (n = 36/203, 18%). A tenth described preceding delayed or misinterpreted results (n = 23/203, 11%; Table 2, Examples 11–13). Contributing patient factors were commoner in this incident type than others (n = 45/131, 34%) and included symptoms which could be attributed to existing morbidity (Table 2, Example 14). The complex management of multi-morbidity and lack of guidance also featured. Staff factors were described in a third of reports in this sample (n = 40/131, 31%) and included misinterpreting investigation results. System factors (n = 46/131, 35%) such as deficiencies in investigation follow-up protocols were also evident.

Driver diagram

Our findings are mapped onto a driver diagram and highlight three main sources of unsafe care as the priority areas for change identified from these reports. (Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Driver diagram to show potential interventions to improve the safety of primary care for older adults.

Discussion

Our study is the largest examination of the pattern of unsafe primary care delivered to older adults [9]. We drew on the largest database of patient safety incident reports in the world. We used a detailed coding and exploratory analytical process, developed specifically for primary care, to enable an evaluation of the main sources and underlying factors potentially influencing the safety of care.

From this weighted sample of reports involving older adults being treated in primary care settings, we found that incidents were most commonly due to one of three inadequate processes: inappropriate medication provision; communication failures across care boundaries; and errors in clinical decision-making. Whilst a fifth of reports in our sample described a serious patient harm outcome, scrutiny of the descriptions in the remainder of reports suggested that many could have escalated into more serious outcomes if healthcare professionals or relatives had not intervened.

The limitations of this study included that inferences from our data are essentially inductive, owing to the selection bias in submission of reports to the NRLS, and also cannot be viewed as representative or generalisable since our sampling strategy prioritised most recent and harmful incidents. However, analysis of safety incidents identified by healthcare professionals can provide insight into what happened and the perceived causes unlike other research methods. Our structured process to characterise the most frequent and harmful incident types from a large volume of data highlights areas of action to improve patient safety in older adults. The literature searches complement these findings, but full systematic reviews may have described other interventions.

This study highlights how dependent older adults are on the healthcare system to document and communicate essential information regarding their care. Human factors such as misread drug names and system weaknesses such as poor communication systems or inadequate protocols were more commonly described to contribute to the incidents than patient-related factors such as multi-morbidity and polypharmacy. The safety of primary care for older adults could be improved by permanent system-level interventions, particularly those that seek to minimise human factor-related causes of harm (Figure 1) [18].

Timely electronic transfer of information with standardised formats and forcing functions [19], may consequently reduce medication and clinical decision-making incidents. Electronic, evidence-based alerts could reduce inappropriate prescribing [20], whilst expanded use of electronic or bar-code drug administration in community settings could tackle other sources of drug administration incidents [21]. ‘Look-alike’ and ‘sound-alike’ medicine solutions to prevent dispensing and administration incidents needs further research and may include: tall man lettering; electronic dispensing alerts and barcode scanners [22]. National or global polices to introduce these initiatives could improve the safety of primary care for older adults.

Previous studies have described other potential solutions to prevent medication incidents. These include ‘deprescribing’ to address polypharmacy and declining physiological function in older adults; [23] here, shared decision-making, including family or carer advocates, can play a pivotal role [24]. Validated medication review tools are available to assist this process [25], which can include pharmacists [26]. Emerging technology that permits community-based point of care testing is reducing unsafe anticoagulation [27], and could be expanded to other therapeutic agents.

New multidisciplinary community-based care models with improved access to specialist geriatric advice may improve complex clinical decision-making and management of multi-morbidity in older adults, thereby reducing the harm associated with these areas that our study has identified [28, 29]. Local protocols within the multidisciplinary team need to ensure an effective system of investigation result follow-up [30], especially for those patients unable to take ownership of their own results.

Conclusion

Priority areas for further research to determine the burden and preventability of unsafe primary care for older adults, include: the timely electronic transfer of information between healthcare settings; electronic tools for prescribing, dispensing and administering medication in the community; and, better clinical decision-making support and guidance.

Key points.

Older adults are at risk of health-care-related harm in primary care settings.

The main sources of unsafe care identified from analysis of patient safety incident reports were due to medication-related incidents, communication-related incidents, and clinical decision-related incidents.

Further research is needed in these priority areas to improve the safety of primary care for older adults.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

All co-authors are contributing to a project funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) program (project number 12/64/118). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR program, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health. A.C.S. and A.E. are co-chief investigators, and L.J.D., A.S. and A.A. are co-applicants of the NIHR HS&DR funded study to characterise primary care patient safety incident reports. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Improving General Practice—A Call to Action https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/igp-cta-evid.pdf

- 2. Panesar SS, Carson-Stevens A, Cresswell KM et al. . How safe is primary care? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2016; 25: 544–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsang C, Bottle A, Majeed A, Aylin P. Adverse events recorded in English primary care: observational study using the General Practice Research Database. Br J Gen Pract 2013; 63: e534–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Avery AJ, Ghaleb M, Barber N et al. . The prevalence and nature of prescribing and monitoring errors in English general practice: a retrospective case note review. Br J Gen Pract 2013; 63: e543–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De Wet C, Bowie P. The preliminary development and testing of a global trigger tool to detect error and patient harm in primary-care records. Postgrad Med J 2009; 85: 176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thomas EJ, Brennan TA. Incidence and types of preventable adverse events in elderly patients: population based review of medical records. BMJ 2000; 320: 741–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sari AB, Cracknell A, Sheldon TA. Incidence, preventability and consequences of adverse events in older people: results of a retrospective case-note review. Age Ageing 2008; 37: 265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donaldson LJ, Panesar SS, Darzi A. Patient-safety-related hospital deaths in England: thematic analysis of incidents reported to a national database, 2010–2012. PLoS Med 2014; 11: e1001667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carson-Stevens A, Hibbert P et al. . A cross-sectional mixed methods study protocol to generate learning from patient safety incidents reported from general practice. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e009079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rees P, Edwards A, Powell C et al. . Patient safety incidents involving sick children in primary care in England and Wales: a mixed methods analysis. PloS Med 2017; 14: e1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cresswell KM, Panesar SS, Salvilla SA. Global research priorities to better understand the burden of iatrogenic harm in primary care: an international Delphi exercise. PLoS Med 2013; 10: e1001554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A Mandate from the Government to the NHS Commissioning Board: April 2013 to March 2015 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/256497/13-15_mandate.pdf

- 13.World Health Report 2008 - Primary Health Care, Now More Than Ever: World Health Organisation; 2008http://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_en.pdf

- 14. Oliver D, Foot C, Humphries R. Making Our Health and Care Systems Fit for an Ageing Population. The King's Fund, London, UK. 2014. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/making-health-care-systems-fit-ageing-population-oliver-foot-humphries-mar14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Reporting and Learning System http://www.nrls.nhs.uk/report-a-patient-safety-incident/

- 16. WHO The Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/taxonomy/publications/en/

- 17. Bennett B, Provost L. What's your theory? Driver diagram serves as a tool for building and testing theories for improvement. Qual Progr 2015: 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Root cause analysis tools U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; 2015http://www.patientsafety.va.gov/docs/joe/rca_tools_2_15.pdf

- 19. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Jama 2007; 297: 831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Poon E, Keohane C, Yoon CS et al. . Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Emmerton L, Rizk M. Look-alike and sound-alike medicines: risks and ‘solutions’. Int J Clin Pharm 2012; 34: 4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scott I, Hilmer S, Reeve E et al. . Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jansen J, Naganathan V, Carter S et al. . Too much medicine in older people? Deprescribing through shared decision making. BMJ 2016; 353: i2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gallagher PF, O'Connor MN, O'Mahony D. Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/START criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 89: 845–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA et al. . A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised, controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. The Lancet 2012; 379: 1310–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharma P, Scotland G, Cruickshank M et al. . The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of point-of-care tests (CoaguChek system, INRatio2 PT/INR monitor and ProTime Microcoagulation system) for the self-monitoring of the coagulation status of people receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy, compared with standard UK practice: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess (Rockv) 2015; 19: 1–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Conroy SP, Stevens T, Parker SG, Gladman JR. A systematic review of comprehensive geriatric assessment to improve outcomes for frail older people being rapidly discharged from acute hospital:‘interface geriatrics’. Age Ageing 2011; 40: 436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith SM, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O'Dowd T. Managing patients with multimorbidity: Systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ 2012; 345: e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Litchfield I, Bentham L, Hill A, McManus RJ, Lilford R, Greenfield S. Routine failures in the process for blood testing and the communication of results to patients in primary care in the UK: a qualitative exploration of patient and provider perspectives. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 24: 681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]