Abstract

Background

older people with dementia admitted to hospital for acute illness have higher mortality and longer hospital stays compared to those without dementia. Cognitive impairment (CI) is common in older people, and they may also be at increased risk of poor outcomes.

Methods

retrospective observational study of unscheduled admissions aged ≥75 years. Admission characteristics, mortality rates and discharge outcomes were compared between three groups: (i) known dementia diagnosis (DD), (ii) CI but no diagnosis of dementia and (iii) no CI.

Results

of 19,269 admissions (13,652 patients), 19.8% had a DD, 11.6% had CI and 68.6% had neither. Admissions with CI or DD were older and had more females than those with no CI, and were more likely to be admitted through the Emergency Department (88.4% and 90.7%, versus 82.0%) and to medical wards (89.4% and 84.4%, versus 76.8%). Acuity levels at admission were similar between the groups. Patients with CI or DD had more admissions at ‘high risk’ from malnutrition than patients with no CI (28.0% and 33.7% versus 17.5%), and a higher risk of dying in hospital (11.8% [10.5–13.3] and 10.8% [9.8–11.9] versus (6.6% [6.2–7.0])).

Conclusions

the admission characteristics, mortality and length of stay of patients with CI resemble those of patients with diagnosed dementia. Whilst attention has been focussed on the need for additional support for people with dementia, patients with CI, which may include those with undiagnosed dementia or delirium, appear to have equally bad outcomes from hospitalisation.

Keywords: Cognitive impairment, older adults, hospital admission, mortality, dementia

Introduction

An estimated 850,000 people in the United Kingdom are living with dementia, with an expected rise to over 1 million by 2021 [1]. People with dementia are more likely to be admitted to hospital due to acute illness [2], and have increased mortality in hospital and after discharge [3, 4]. Contributing factors to mortality include comorbidities, poorer functional and nutritional status [5, 6], more severe cognitive impairment (CI) [7] and increased risk of delirium [8, 9]. The complexity of their condition requires a high level of resource from a wide range of specialised services to provide appropriate clinical management [10, 11]. Patients with dementia are more likely to develop hospital-acquired complications, including urinary tract infections, pressure ulcers and pneumonia, which are associated with an 8-fold increase in length of stay and a doubling in the estimated mean episode cost [12].

A prospective study of dementia diagnostic assessment in a cohort of hospitalised patients aged 70 and above revealed half of the patients with dementia had not received a diagnosis prior to admission [7]. Patients without a prior diagnosis may be at additional risk from worsening of their condition in hospital, as they may not benefit from care intended to meet the needs of patients with dementia, e.g. close observation of food and fluid intake, avoidance of sedatives and antipsychotics, reduced movement between wards to avoid further confusion and beds near clear signage to toilets [13–15]. To improve identification of dementia patients in hospital and contribute towards improved diagnosis of dementia in the general population, dementia screening became a requirement in hospitals in the UK in 2014. In addition to identifying patients with pre-diagnosed dementia, all unscheduled admissions aged 75 years and above are to be screened for dementia using simple cognitive tests practicable within an acute hospital setting (e.g. the Abbreviated Mental Test Score—AMTS) within 72 hours of admission [16,17]. If patients are found to have CI, further assessments or referrals are required to establish the cause, which may range from mild CI, infection or trauma through to severe delirium or dementia.

Although this process improves the systematic detection of patients with dementia in hospital, many patients with CI may not be fully assessed until much later during hospital admission, or referred for general practitioner (GP) assessment after discharge. There are currently no large-scale data available on the proportion of older patients identified as having CI but no prior diagnosis of dementia through this process. It is also not known whether these patients are at increased risk for poor outcomes. Using routinely collected dementia screening data in a large acute district general hospital, we aim to describe the characteristics of this patient group, and to ascertain whether their mortality and length of stay is similar to patients with diagnosed dementia. Such information is essential for planning appropriate clinical services and person-centred care for this group of patients, with the aim of reducing adverse outcomes.

Methods

Objectives

To estimate the prevalence of CI in patients without a diagnosis of dementia in acute, non-elective hospital admissions of patients aged ≥75 years. To describe clinical characteristics, healthcare pathway, mortality and length of stay according to CI/dementia status.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

An English district general hospital serving approximately 675,000 people.

Data collection

Dementia screening

Dementia screening is performed using an electronic hand-held device (Vitalpac®, System C, London) by trained clinical staff. Patients with a known diagnosis of dementia are identified. For patients with no known diagnosis of dementia, the following questions are asked: (1) Is the patient exhibiting disturbed behaviour? (2) Has the patient been increasingly forgetful over the last 12 months so that it has had an impact on their daily life? If the answer to one or both of the questions is ‘yes’, an AMTS is performed. Delirium is also recorded if present in patients with disturbed behaviour. Patients with an AMTS of eight or below are referred to the GP for assessment at discharge.

Patient and health service use

Demographic data, admission route, admitting specialty, admission and discharge dates, diagnoses (International Classification of Disease 10), death in hospital and discharge destination are entered into the Patient Administration System from clinical notes. Vital signs (temperature, systolic blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, consciousness level, oxygen saturation, use of supplemental oxygen) are recorded electronically and a National Early Warning Score (NEWS) of 0–20 generated [18]. The NEWS score indicates the patient's risk of deterioration and death within the next 24 hours. Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) scores and Body Mass Index (BMI) are recorded.

Data extraction

Anonymised clinical records data of acute, non-elective admissions aged 75 and above with at least one dementia screening record between 29th January 2014 (initiation of electronic dementia screening system) and 19th October 2015 inclusive were extracted into a Microsoft Access database.

Analysis

Analyses were performed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Summary statistics were calculated for the steps in the screening pathway. Admissions were categorised into three cohorts: (i) known diagnosis of dementia (DD) (recorded at any point during admission), (ii) CI with no known diagnosis of dementia (CI), defined as a positive response to one/both screening questions ((a) disturbed behaviour, (b) forgetful in last 12 months) and an AMTS of eight or below, (iii) no CI, defined as a negative response to both screening questions, or a positive response to one/both screening questions and an AMTS of 9 or 10 or no AMTS data available.

Estimates of the prevalence of a dementia diagnosis (DD) and CI were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Patient characteristics at admission (age, gender, primary diagnosis according to Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicator classification, NEWS category [18], MUST score (first record), BMI), healthcare pathway data (route of admission and specialty) and discharge characteristics (alive/dead, length of stay, discharge destination) were summarised. Statistical tests of differences in proportions (Chi2—nominal variables; Kruskal–Wallis—ordinal variables) and means/medians (ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis) were performed. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were performed for ANOVA and Chi2 results significant at P < 0.05, and Dunn's test for Kruskal–Wallis.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and South East Hampshire Research Ethics Committee, reference 08/02/1394.

Results

Dementia screening

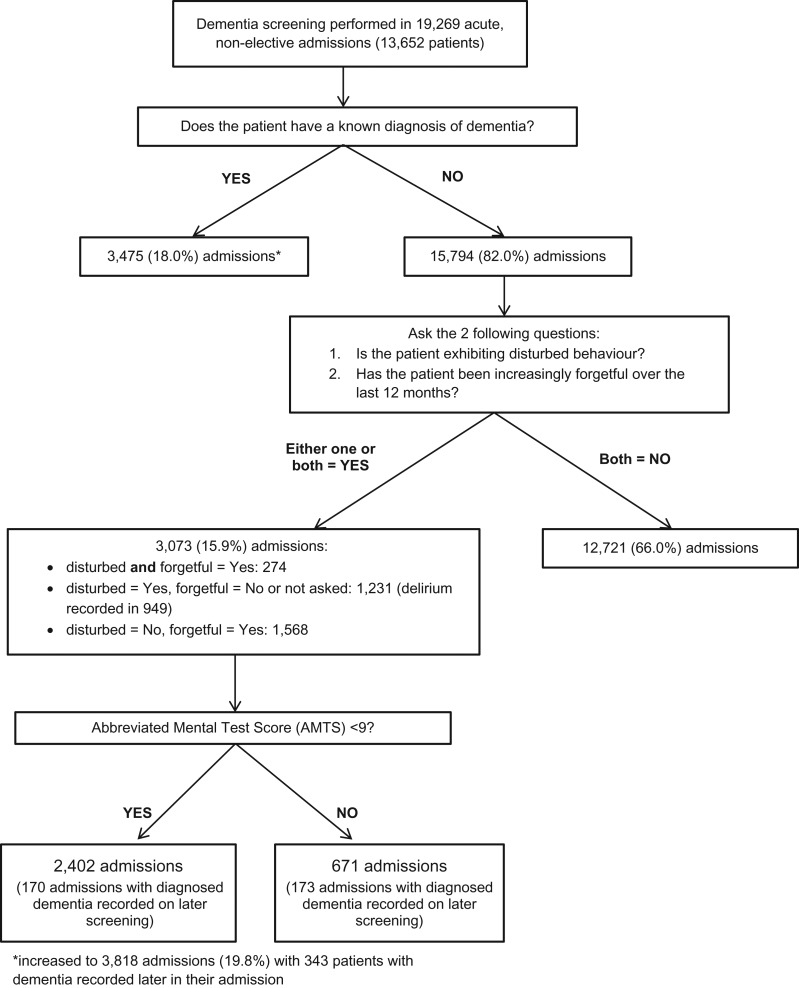

A total of 19,269 admissions (13,652 patients) were screened for dementia (Figure 1), giving a prevalence of diagnosed dementia (DD) of 19.8% (95% CI 19.3–20.4, n = 3,818). The prevalence of CI (no known dementia) was 11.8% (95% CI 11.1–12.0, n = 2,232), with an average AMTS of 4.7 (standard deviation 2.7). No CI was detected in 68.6% (n = 13,219) of admissions.

Figure 1.

Dementia screening process and results.

Characteristics of admitted patients

Demographics of patients with CI or DD were very similar, with a significantly older and more female population as compared to those with no CI (Table 1). Patients with CI or DD were more likely to be admitted through Accident and Emergency (A&E) than those with no CI (88.4% and 90.7% versus 82.0%), and more frequently admitted to Medicine (89.4% and 84.4% versus 76.8% no CI). A primary admission diagnosis of neuropsychiatric disease was more common in patients with CI (10.6%) and DD (9.4%) than those with no CI (2.0%). Delirium was present in 36% (809/2232) of patients with CI. The frequency of admissions for respiratory conditions and conditions related to frailty (falls, fractures and osteoporosis) was similar in all groups, whereas patients with no CI were more likely to be admitted with a primary diagnosis of heart failure, cardiovascular conditions or gastrointestinal disease. There was no significant difference in the acuity category at admission between the groups (Chi2P = 0.113), although patients with DD had significantly higher NEWS values than patients with no CI (Dunn's test P = 0.023). ‘High-risk’ MUST scores were significantly more prevalent in admissions with CI or DD than those with no CI (Dunn's test P < 0.01), with DD admissions being at most risk (33% versus 28.0% CI, 17.5% no CI). The same was observed with BMI categories, with CI and DD admissions having significantly more underweight patients. A sensitivity analysis showed no differences in patient characteristics according to whether or not a MUST record was available. The majority of omissions occurred in patients with short hospital stays.

Table 1.

Characteristics of admissions aged 75 and above according to presence of CI or dementia in 19,269 admissions

| No detected CI or known dementia (‘no CI’) | CI (AMTS < 9) and no known dementia (‘CI’) | Diagnosed dementia (‘DD’) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 13,219 (68.6%) | N = 2,232 (11.6%) | N = 3,818 (19.8%) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 83.4 (5.6) | 86.0 (5.9) | 86.2 (5.6) | P < 0.001a |

| Aged 75–89 years (n, %) | 11,041 (83.5%) | 1,610 (72.1%) | 2,703 (70.8%) | |

| Aged 90 years and above (n, %) | 2,178 (16.5%) | 622 (27.9%) | 1,115 (29.2%) | |

| Gender (n, % male) | 5,952 (45.0%) | 848 (38.0%) | 1,445 (37.9%) | P < 0.001b |

| Admission details | ||||

| Admission route (n, %) | ||||

| Emergency—A+E | 10,825 (82.0%) | 1,972 (88.4%) | 3,462 (90.7%) | P < 0.001b |

| Emergency—GP | 1,281 (9.7%) | 182 (8.2%) | 301 (7.9%) | |

| Emergency—outpatient | 179 (1.4%) | 10 (0.5%) | 5 (0.1%) | |

| Emergency—domiciliary | 14 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.03%) | |

| Other | 920 (7.0%) | 68 (3.1%) | 49 (1.3%) | |

| Admission specialty (n, %) | ||||

| Medicine | 10,155 (76.8%) | 1,996 (89.4%) | 3,223 (84.4%) | P < 0.001b |

| Surgery | 1,793 (13.6%) | 49 (2.2%) | 227 (6.0%) | |

| Trauma and orthopaedics | 944 (7.1%) | 133 (6.0%) | 280 (7.3%) | |

| ENT and oral surgery | 108 (0.8%) | 3 (0.1%) | 12 (0.3%) | |

| Gynaecology | 19 (0.1%) | 1 (0.04%) | 0 | |

| Other | 200 (1.5%) | 50 (2.2%) | 76 (2.0%) | |

| Clinical data on admission (or first record) | ||||

| Primary diagnosis classification (n, %) | ||||

| Heart failure, cardiovascular system | 3,205 (26.0%) | 273 (13.0%) | 481 (13.6%) | P < 0.001b |

| Respiratory | 2,109 (17.1%) | 340 (16.1%) | 659 (18.7%) | |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 1,280 (10.4%) | 88 (4.2%) | 192 (5.4%) | |

| Falls, fractures, osteoporosis | 1,158 (9.4%) | 221 (10.5%) | 438 (12.4%) | |

| Renal/urology | 993 (8.1%) | 285 (13.5%) | 421 (11.9%) | |

| Rheumatology | 629 (5.1%) | 203 (9.6%) | 313 (8.9%) | |

| Infectious diseases | 419 (3.4%) | 111 (5.3%) | 138 (3.9%) | |

| Endocrine/nutritional/blood disorder | 420 (3.4%) | 93 (4.4%) | 142 (4.0%) | |

| Cancer | 417 (3.4%) | 52 (2.3%) | 43 (1.2%) | |

| Neuropsychiatric disease | 248 (2.0%) | 224 (10.6%) | 330 (9.4%) | |

| Skin | 214 (2.0%) | 40 (1.9%) | 65 (1.8%) | |

| Trauma | 214 (2.0%) | 76 (3.6%) | 124 (3.5%) | |

| ENT and eyes | 154 (1.3%) | 23 (1.1%) | 23 (0.7%) | |

| Female reproductive | 16 (0.1%) | 0 | 1 (0.03%) | |

| Other | 808 (6.6%) | 77 (3.7%) | 160 (4.5%) | |

| Missing | 881 | 126 | 288 | |

| NEWS at admission | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1(3) | 2(3) | 2(3) | P = 0.0154c |

| By category: | ||||

| Low acuity (0–4) | 11,316 (85.9%) | 1,888 (84.7%) | 3,194 (83.9%) | P = 0.113c |

| Medium acuity (5–6) | 1,225 (9.3%) | 206 (9.2%) | 369 (9.7%) | |

| High acuity (7 and above) | 635 (4.8%) | 135 (6.1%) | 244 (6.4%) | |

| Missing | 43 | 11 | 3 | |

| MUST score | ||||

| Low risk (0) | 7,033 (73.0%) | 942 (59.0%) | 1,436 (55.9%) | P < 0.001c |

| Medium risk (1) | 909 (9.4%) | 208 (13.0%) | 269 (10.5%) | |

| High risk (2 or more) | 1,689 (17.5%) | 448 (28.0%) | 865 (33.7%) | |

| Missing | 3,588 (27%) | 634 (28%) | 1,248 (33%) | |

| BMI | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 25.4 (5.3) | 24.5 (5.4) | 23.8 (4.7) | P < 0.001a |

| By category: | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 665 (7.3%) | 146 (10.8%) | 233 (11.3%) | P < 0.001c |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 3,999 (44.1%) | 648 (47.7%) | 1,097 (53.4%) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 2,894 (31.9%) | 358 (26.4%) | 523 (25.4%) | |

| Obese (30–39.9) | 1,390 (15.3%) | 189 (13.9%) | 192 (9.3%) | |

| Morbidly obese (40 and above) | 118 (1.3%) | 17 (1.3%) | 11 (0.5%) | |

| Missing | 4,153 (31%) | 874 (39%) | 1,762 (46%) | |

aANOVA.

bChi2.

cKruskal–Wallis. ENT, ear, nose and throat; IQR, inter-quartile range.

Discharge characteristics

More than 60% of admissions with CI or DD stayed at least 1 week (67% and 61%), as compared to patients with no CI (45%) (Table 2). CI patients had significantly longer stays than both of the other groups (post hoc Dunn's tests P < 0.001). More admissions with CI or DD died in hospital than those with no CI (11.8% and 10.8% versus 6.6%), and admissions with CI or DD had a comparable proportion of deaths in hospital (post hoc Chi2P = 0.201) and a similar mortality rate (22.7 and 22.0 deaths/100 patient months in hospital). The mortality rate of CI patients with delirium was 23.0 deaths/100 patient months [19.2–27.4], compared to 15.9 [11.6–21.3] for CI patients with no delirium. Patients with CI or DD were more likely to be discharged to a nursing or residential home for the first time (11.3% and 16.3%) than patients with no CI (3.5%). Admissions with CI were significantly more likely to be discharged to another hospital location, e.g. a specialist mental health unit or rehabilitation ward, for further care (13.3% versus 8.2% DD, 8.1% no CI).

Table 2.

Discharge characteristics according to the presence of dementia/CI at admission.a

| No detected CI or known dementia | CI (AMTS <9) and no known dementia | Diagnosed dementia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 12,974 (68.7%) | N = 2,180 (11.5%) | N = 3,730 (19.8%) | ||

| Length of stay | ||||

| Length of stay (median, IQR) | 6 (11) | 11 (16) | 9 (17) | P < 0.001b |

| Length of stay by category: | ||||

| Less than 24 hours (0 days) | 647 (5.0%) | 58 (2.7%) | 165 (4.4%) | P < 0.001b |

| 1–6 days | 6,450 (49.7%) | 656 (30.1%) | 1,309 (35.1%) | |

| 7–13 days | 2,763 (21.3%) | 567 (26.0%) | 840 (22.5%) | |

| 14–27 days | 1,946 (15%) | 537 (24.6%) | 839 (22.5%) | |

| 28 days or more | 1,168 (9%) | 362 (16.6%) | 577 (15.5%) | |

| Mortality | ||||

| Status at discharge (n, %): | ||||

| Alive | 12,114 (93.4%) | 1,922 (88.2%) | 3,329 (89.3%) | P < 0.001c |

| Dead | 860 (6.6% [6.2–7.0]) | 258 (11.8% [10.5–13.3]) | 401 (10.8% [9.8–11.9]) | |

| Mortality rate/100 person months of admission | 18.7 [17.5–20.0] | 22.7 [20.0–25.7] | 22.0 [19.9–24.3] | |

| (4,590 months) | (1,136 months) | (1,821 months) | ||

| Discharge destination (for patients discharged alive) | ||||

| Discharge destination (n, %) | ||||

| Usual residence | 10,350 (85.4%) | 1,361 (70.8%) | 2,384 (71.6%) | P < 0.001c |

| Nursing/residential homed | 429 (3.5%) | 218 (11.3%) | 543 (16.3%) | |

| Hospice | 132 (1.1%) | 43 (2.2%) | 57 (1.7%) | |

| Other hospital location | 978 (8.1%) | 256 (13.3%) | 274 (8.2%) | |

| Other | 225 (1.9%) | 44 (2.3%) | 71 (2.1%) | |

aN = 18,884 admissions (no discharge data for 385 (2.0%) admissions.

bKruskal–Wallis.

cChi2.

dWhere the patient has not previously been in a nursing/residential home.

Discussion

This analysis of 19,269 unscheduled hospital admissions revealed that 11.6% of patients aged ≥75 are cognitively impaired but have no prior diagnosis of dementia. These patients had similar demographics and acuity at admission to patients with dementia. Both groups had high rates of nutritional risk and a significantly higher risk of dying in hospital than patients with no CI. The length of stay for patients with CI was significantly longer than those with a prior diagnosis of dementia, and more patients were discharged to further hospital care.

The significant prevalence of CI in this cohort and their characteristics suggests that undiagnosed dementia in the community is still common, and that systematic detection of CI in hospital should contribute to triggering further assessment [17, 19, 20]. Given previous work, it is likely that around 50% of admitted older persons with CI in this cohort may actually have had undiagnosed dementia, with their additional risk of adverse outcomes [7]. More than a third of patients with CI in this cohort were delirious when screened, which may indicate pre-existing mild CI or dementia [21], and contributes to longer stays in hospital and increased mortality [22]. Hospital in-patients with CI are predisposed to develop delirium during their stay [9], and so systematic screening for CI should aid identification of patients who would benefit from closer monitoring for delirium and consequent timely management. Although longer hospital stays for patients with CI and DD may have reflected deterioration of the patient's condition due to complications arising during hospitalisation such as infections and falls [22, 23], delays in transfer of care to social, rehabilitative or nursing home care is also likely to have increased length of stay [24]. This is highlighted by 16% of patients with dementia being discharged to a nursing/residential home, rather than their usual place of residence, and 13% of patients with CI discharged to other hospital locations.

The comparable acuity at admission between the groups in this cohort and the significant numbers of patients with CI and DD who had NEWSs indicating the need for close monitoring and escalation and the diversity of clinical reasons for admission suggest that many of this population need timely and appropriate in-hospital care. Acute hospitals may have procedures in place to improve care for patients identified as having dementia at admission, which may not currently be employed for patients with CI. Policies for quick assessment and early discharge for patients with dementia shortens length of stay and reduces risk of deterioration in hospital. A ‘red tray’ system can be used, providing meals on a red tray indicating to staff that patients require extra support with feeding and the tray should not be cleared until the patient has eaten as much as possible. More than one quarter of admissions with CI had high-risk MUST scores, highlighting the potential benefit of providing this additional group of patients with assistance at mealtimes, as their CI may have contributed to a worsening in their nutritional status during admission, and consequently increased their mortality risk [25]. Symbolic indicators can be used to alert all healthcare and domiciliary staff to the additional needs of the dementia patients, for example a ‘forget-me-not’ magnet near the bed. Whilst this may improve person-centred care for patients with a diagnosis of dementia, a similar symbol may also benefit those with CI who are still to be further assessed, to increase the opportunities for positive care in the interim. As seen in this cohort, information on a current DD may not be available to staff until later on in the patient's admission, thus leaving a period within which the patient may not have had access to appropriate care. The placement of patients with CI in appropriate wards where staff are more familiar with managing cognitively impaired patients, i.e. Medicine for Older People wards, may also be important to consider, as the majority of presenting complaints are medical and may be managed in medical wards. Development of ‘best practice’ for this patient group to impact on clinical outcomes remains a challenge, and it is unclear how many patients may receive individual interventions, although initiatives including specialist medical and mental health units and dementia champions can improve patient and carer satisfaction [26–29].

Limitations of this analysis include the pragmatic nature of the screening system, which has not been validated in acute general hospitals, as well as difficulties in establishing whether a patient had a diagnosis of dementia at the point of hospital admission, which may have led to misclassification of the groups. Delirium was only coded in patients with disturbed behaviour, and may have underestimated patients with hypoactive delirium, although it is likely these patients were included in the CI group. Practical difficulties in weighing and measuring patients may have contributed to missing BMI data in patients with CI and dementia. However, the data set overall has high rates of completion, and regular audits and training assist accuracy.

Conclusions

The significant numbers of cognitively impaired older people without a DD admitted to acute hospitals, and their comparable risk of in-hospital death and length of stay to patients with diagnosed dementia, indicate that there is a need to improve identification of this vulnerable population in primary and secondary care. This needs to be combined with improved management in hospital, including vigilance for deterioration and earlier identification of needs at discharge to enable engagement with the necessary services and shorten hospital stay. Further research characterising longitudinal patterns of risk indicators in these patients may inform effective changes in care.

Key points.

Patients with dementia have higher in-hospital mortality and longer hospital stays.

In this study, 11.6% of unscheduled admissions aged ≥75 had cognitive impairment, but no prior dementia diagnosis.

These patients had a comparable risk of dying in hospital to patients with dementia, and longer lengths of stay.

Person-centred care such as that used for people with dementia may also be appropriate for these patients.

Further research is required to explore contributory factors to the poor outcomes in this patient group.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the concept of the paper. P.M. contributed to the acquisition of data. C.F. performed the analysis and drafted the paper. P.G., G.G., J.B. and P.M. revised the drafts and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Wessex Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Fellow programme, and the Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust Research and Innovation department.

Disclaimer

The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (Wessex) at Portsmouth Hospitals Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

- 1. Dowrick A, Southern A. Dementia 2014: Opportunity for Change. London: Alzheimer's Society, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toot S, Devine M, Akporobaro A, Orrell M. Causes of hospital admission for people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14: 463–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sampson EL, Leurent B, Blanchard MR, Jones L, King M. Survival of people with dementia after unplanned acute hospital admission: a prospective cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013; 28: 1015–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borson S, Frank L, Bayley PJ et al. Improving dementia care: the role of screening and detection of cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 2013; 9: 151–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zekry D, Herrmann FR, Grandjean R et al. Does dementia predict adverse hospitalization outcomes? A prospective study in aged inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009; 24: 283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stratton RJ, King CL, Stroud MA, Jackson AA, Elia M. ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ predicts mortality and length of hospital stay in acutely ill elderly. Br J Nutr 2006; 95: 325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2009; 195: 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Travers C, Byrne GJ, Pachana NA, Klein K, Gray LC. Prospective observational study of dementia in older patients admitted to acute hospitals. Australas J Ageing 2014; 33: 55–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ryan DJ, O'Regan NA, Caoimh RO et al. Delirium in an adult acute hospital population: predictors, prevalence and detection. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e001772. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glover A, Bradshaw LE, Watson N et al. Diagnoses, problems and healthcare interventions amongst older people with an unscheduled hospital admission who have concurrent mental health problems: a prevalence study. BMC Geriatr 2014; 14: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lakey L. Counting the Cost: Caring for People with Dementia on Hospital Wards. London: Alzheimer's Society, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bail K, Goss J, Draper B, Berry H, Karmel R, Gibson D. The cost of hospital-acquired complications for older people with and without dementia; a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andrews J, Christie J. Emergency care for people with dementia. Emerg Nurse 2009; 17: 12, 4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Archibald C. Meeting the nutritional needs of patients with dementia in hospital. Nurs Stand 2006; 20: 41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Archibald C. Promoting hydration in patients with dementia in healthcare settings. Nurs Stand 2006; 20: 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Commissioning for quality and innovation (CQUIN ): 2013/14 Guidance. London: NHS Commissioning Board, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Commissioning for quality and innovation (CQUIN) : 2014/15 Guidance. In: NHS England, editor. February 2014.

- 18. National Early Warning Score (NEWS): Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS Report of a Working Party. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009; 23: 306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldberg SE, Whittamore KH, Harwood RH, Bradshaw LE, Gladman JR, Jones RG. The prevalence of mental health problems among older adults admitted as an emergency to a general hospital. Age Ageing 2012; 41: 80–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jackson TA, MacLullich AM, Gladman JR, Lord JM, Sheehan B. Undiagnosed long-term cognitive impairment in acutely hospitalised older medical patients with delirium: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing 2016; 45: 493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsieh SJ, Madahar P, Hope AA, Zapata J, Gong MN. Clinical deterioration in older adults with delirium during early hospitalisation: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e007496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allan LM, Ballard CG, Rowan EN, Kenny RA. Incidence and prediction of falls in dementia: a prospective study in older people. PloS One 2009; 4: e5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Audit Office Discharging Older Patients from Hospital. In: Health Do, editor. London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Henderson S, Moore N, Lee E, Witham MD. Do the malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST) and Birmingham nutrition risk (BNR) score predict mortality in older hospitalised patients. BMC Geriatr 2008; 8: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Champion E. Person-centred dementia care in acute settings. Nurs Times 2014; 110: 23–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilkinson I, Coates A, Merrick S, Lee C. Junior doctor dementia champions in a district general hospital (innovative practice). Dementia (London, England) 2016; 15: 263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Banks P, Waugh A, Henderson J et al. Enriching the care of patients with dementia in acute settings? The Dementia Champions Programme in Scotland. Dementia (London, England) 2014; 13: 717–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goldberg SE, Bradshaw LE, Kearney FC et al. Care in specialist medical and mental health unit compared with standard care for older people with cognitive impairment admitted to general hospital: randomised controlled trial (NIHR TEAM trial). BMJ 2013; 347: f4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]