Abstract

We studied the associations of leukocyte telomere length (LTL) with all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality in 12,199 adults participating in 2 population-based prospective cohort studies from Europe (ESTHER) and the United States (Nurses’ Health Study). Blood samples were collected in 1989–1990 (Nurses’ Health Study) and 2000–2002 (ESTHER). LTL was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. We calculated z scores for LTL to standardize LTL measurements across the cohorts. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate relative mortality according to continuous levels and quintiles of LTL z scores. The hazard ratios obtained from each cohort were subsequently pooled by meta-analysis. Overall, 2,882 deaths were recorded during follow-up (Nurses’ Health Study, 1989–2010; ESTHER, 2000–2015). LTL was inversely associated with age in both cohorts. After adjustment for age, a significant inverse trend of LTL with all-cause mortality was observed in both cohorts. In random-effects meta-analysis, age-adjusted hazard ratios for the shortest LTL quintile compared with the longest were 1.23 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.04, 1.46) for all-cause mortality, 1.29 (95% CI: 0.83, 2.00) for cardiovascular mortality, and 1.10 (95% CI: 0.88, 1.37) for cancer mortality. In this study population with an age range of 43–75 years, we corroborated previous evidence suggesting that LTL predicts all-cause mortality beyond its association with age.

Keywords: aging, all-cause mortality, cancer mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, cohort studies, leukocytes, telomere length

Telomeres are special chromatin structures found at the ends of chromosomes which are comprised of a stretch of repetitive DNA (TTAGGG) and a variety of specifically bound proteins. Depending on the age, tissue type, chromosomes, and replicative history of cells, the length of telomeres can vary between 0.5 kilobase pairs and 15 kilobase pairs, with approximately 30–200 base pairs being lost after each mitotic cell division in somatic cells (1, 2). This leads to a gradual shortening of telomeres with age (3, 4), due to incomplete replication of linear chromosomes by DNA polymerases (5). Critically short telomere length leads to cell senescence and apoptosis (6).

A number of epidemiologic studies, with varying sample sizes and characteristics, have yielded inconsistent results with regard to the link between leukocyte telomere length (LTL) and mortality (3). Regarding cause-specific mortality such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality and cancer mortality, results have also been inconsistent. The reported associations between LTL and CVD indicate a modest inverse link (7–10) but are heterogeneous with regard to CVD mortality (11–13). The associations of LTL with cancer seem to be even more complex. A number of studies have found increased risk of cancer incidence (14–18) with short LTL and mixed results on cancer mortality (11, 12, 18). However, more recent studies investigating cancer-specific associations have also correlated longer LTL with increased risk of certain malignancies, including pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, sarcoma, and lung adenocarcinoma (19–24). With regard to all-cause mortality, several recent prospective cohort studies could not establish an association between LTL and all-cause mortality (12, 25, 26), while the largest study carried out to date, comprising a cohort of nearly 65,000 Danish individuals, found linear graded associations of LTL with all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality (27).

Considering the inconsistent findings in the literature, which could be due to a lack of statistical power in most of the studies, we aimed to further investigate the association of LTL with all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality in 2 large independent cohorts in the Consortium on Health and Ageing: Network of Cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES).

METHODS

Study design and participants

Data from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the ESTHER study (Epidemiological Study on the Chances of Prevention, Early Recognition, and Optimized Treatment of Chronic Diseases in the Older Population) were used. Both are ongoing prospective cohort studies from the United States and Germany, respectively, and both are included in the CHANCES consortium (28).

The NHS is a prospective cohort study of 121,700 female registered nurses in 11 US states who were 30–55 years of age at enrollment. In 1976 and biennially thereafter, self-administered questionnaires gathered detailed information on lifestyle, menstrual and reproductive factors, and medical history. Self-reports of major chronic diseases in the NHS are confirmed by reviews of medical records and pathology reports, telephone interviews, or supplemental questionnaires. From 1989 to 1990, a total of 32,826 women provided blood samples. NHS blood collection methods have been previously described in detail (29). The current analysis included data from 8,633 women who were selected to participate in different nested case-control studies. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using QIAmp (Qiagen, Chatsworth, California) 96-spin blood control. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts).

The ESTHER study is an ongoing cohort study with the main objective of improving the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of chronic age-related diseases. Overall, 9,949 men and women aged 50–75 years in Saarland, southwestern Germany, were recruited by their general practitioners during a general health check-up between July 2000 and December 2002 and have been followed since then with respect to incidence of major diseases and deaths. Information on age, sex, sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, health status, family history, and lifestyle factors was obtained by means of detailed questionnaires in a standardized manner. Whole blood samples were obtained from all participants from peripheral blood. The current analysis was based on 3,566 participants for whom measurements of LTL in baseline blood samples were available. They were a representative subsample of the entire study population, whose extracted DNA became available first (a comparison of this subsample with the overall ESTHER sample is given in Web Table 1, available at http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/). Genomic DNA was extracted by means of the high salt method and stored at −20°C. The ESTHER study has been approved by the ethics committees of the medical faculty of the University of Heidelberg and of the medical board of the state of Saarland. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measurements

LTL measurements were performed independently in different laboratories. In both studies, DNA concentration was quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts), and relative telomere lengths, in genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes, were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (30). This method determines the copy number ratio between telomere repeats and a single copy reference gene (the T/S ratio) in experimental samples relative to a reference sample. The T/S ratio is proportional to average telomere length because the amplification is proportional to the number of primer binding sites in the first cycle of the PCR reaction. Relative telomere length was calculated as the exponentiated T/S ratio. Two quality-control samples were inserted into each PCR plate in order to assess the coefficients of inter- and intraplate variability. Quantitative PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, California) in the NHS and using the LightCycler 480 System (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in the ESTHER study.

Terminal restriction fragment analysis was additionally performed in a subsample (n = 20) of the ESTHER study population to validate our results from the quantitative PCR measurements and obtain absolute LTL in base pairs. Briefly, 3.5 μg of genomic DNA was digested overnight at 37°C with the restriction enzymes HphI and MnlI (Fisher Scientific GmbH, Schwerte, Germany) and loaded onto 0.7% agarose gel with digoxigenin-labeled marker (DNA Molecular Weight Marker VII, DIG-Labeled; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Then, DNA was processed as previously described (31). Detection of the digoxigenin-labeled probe and marker was performed using Anti-Digoxigenin-AP, Fab fragments (Roche Diagnostics) and CDP-Star chemiluminescent substrate (Roche Diagnostics). Image analysis was done with ImageJ Analysis Software, version 1.44 (32).

Statistical analyses

The correlation between relative LTL measurements and absolute LTL measurements was 0.622 (P = 0.005). The coefficients of variation for the telomere assay of quality control samples were 6.5% and 5.3% in the ESTHER cohort and less than 4% for triplicates in the NHS cohort.

In order to standardize LTL measurements across cohorts, we applied a z transformation. This means that measurements were transformed in a way that the mean value was zero and the standard deviation was 1; that is, after transformation, LTL measurements were expressed in units of the standard deviation. The differences in the associations of z score quintiles with age, lifestyle factors, and health-related outcomes were tested for statistical significance by analysis of variance.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the associations of LTL with all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality both in the whole cohort and by sex and age group (50–59 years and ≥60 years). A shared frailty model was fitted with measurement batch as a random effect in order to account for within-batch correlations. Continuous z score levels, quintiles of z scores, and dichotomized z scores (z score less than median and z score greater than or equal to median) were used as exposure variables in regression models.

Regression models with 4 different levels of adjustment were used. Model 1 was the crude model without any covariates and adjustment only for batch effect; model 2 adjusted for batch and age (and also sex in the ESTHER cohort); model 3 additionally adjusted for potential further confounders, including smoking status (never, former, or current smoking), body mass index (defined as weight (kg)/squared height (m2); ≤18.5, 18.6–24.9, 25–29.9, or ≥30), alcohol consumption (abstainer, low intake, medium intake, or high intake; intakes were defined as follows: men—0.1–39.9 g/week, 40–59.9 g/week, and ≥60 g/week, respectively; women—0.1–19.9 g/week, 20–39.9 g/week, and ≥40 g/week, respectively (33)), physical activity (inactive or active; defined as 0 hours of vigorous physical activity per week or >0 hours of vigorous physical activity per week), and years of education. Model 4 further adjusted for systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), total cholesterol level (mmol/L), the presence of diabetes, and history of myocardial infarction, cancer, and stroke. The additional variables included in model 4 might not necessarily be considered potential confounders of the association between LTL and mortality, but they could be considered potential mediators of LTL-mortality associations. Following the estimation of study-specific hazard ratios, we carried out meta-analyses to calculate summary hazard ratios across the cohorts. In a conservative approach, the random-effects estimates were taken as “main results” to allow for variation of true effects across studies. Random-effects estimates were derived using the DerSimonian–Laird method (34). All variables used for the project were created by each cohort according to the previously-agreed-upon harmonization rules of the CHANCES consortium.

All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina), and statistical tests were 2-sided, using a 5% significance level. R software, version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and the R package “meta” were used to carry out the meta-analysis (35).

RESULTS

The general characteristics of the study populations according to age-adjusted quintiles of LTL z scores are shown in Table 1. There were 8,633 and 3,566 eligible participants from the NHS and ESTHER cohorts, respectively. The age range in the NHS was 42.7–70.2 years, with a mean age of 59.0 (standard deviation (SD), 6.6) years. The age range in the ESTHER cohort was 50–75 years, with a mean age of 61.9 (SD, 6.6) years. After a mean follow-up duration of 18.4 (SD, 3.8) years, 2,149 deaths were recorded in the NHS. After 12.5 (SD, 2.9) years of follow-up, there were 733 deaths in the ESTHER cohort. Age was inversely associated with LTL in both cohorts (P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population According to Quintile of Age-Adjusted Leukocyte Telomere Length, Nurses’ Health Study (1989–2010) and ESTHER (2000–2015)

| Characteristic | Quintile of Leukocyte Telomere Length z Score | P Valuea | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Shortest) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (Longest) | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SE) | No. of Persons | % | Mean (SE) | No. of Persons | % | Mean (SE) | No. of Persons | % | Mean (SE) | No. of Persons | % | Mean (SE) | No. of Persons | % | ||

| Nurses’ Health Study (n = 8,633) | ||||||||||||||||

| Portion of study population | 1,726 | 20.0 | 1,727 | 20.0 | 1,727 | 20.0 | 1,726 | 20.0 | 1,727 | 20.0 | ||||||

| Age, yearsb | 60.0 (6.3) | 59.3 (6.6) | 59.1 (6.5) | 58.6 (6.7) | 58.1 (6.9) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Male sex | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Body mass indexc | 25.6 (4.9) | 25.6 (4.6) | 25.4 (4.7) | 25.2 (4.8) | 25.4 (4.6) | 0.09 | ||||||||||

| Current smoker | 264 | 19.5 | 286 | 21.1 | 297 | 21.9 | 275 | 20.3 | 235 | 17.3 | 0.08 | |||||

| Vigorous physical activityd | 789 | 19.1 | 836 | 20.3 | 822 | 19.9 | 829 | 20.1 | 852 | 20.6 | 0.62 | |||||

| Education, years | 14.8 (1.4) | 14.8 (1.4) | 14.8 (1.4) | 14.8 (1.4) | 14.9 (1.4) | 0.45 | ||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption, g/day | 5.4 (9.7) | 5.7 (9.6) | 6.0 (10.7) | 5.7 (10.3) | 5.2 (8.6) | 0.13 | ||||||||||

| Total cholesterol level, mmol/L | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.2) | 0.30 | ||||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 127.6 (13.8) | 128.2 (13.9) | 127.0 (13.5) | 127.7 (14.0) | 128.2 (14.0) | 0.08 | ||||||||||

| Chronic disease history | ||||||||||||||||

| Cancer | 72 | 20.1 | 69 | 19.3 | 79 | 22.1 | 74 | 20.7 | 64 | 17.9 | 0.78 | |||||

| Diabetes | 104 | 24.6 | 88 | 20.9 | 83 | 19.7 | 69 | 16.4 | 78 | 18.5 | 0.09 | |||||

| Coronary heart disease | 41 | 22.9 | 38 | 21.2 | 35 | 19.6 | 31 | 17.3 | 34 | 19.0 | 0.80 | |||||

| Stroke | 14 | 28.6 | 12 | 24.5 | 9 | 18.4 | 12 | 24.5 | 2 | 4.1 | 0.06 | |||||

| Mortality | ||||||||||||||||

| Cancer | 158 | 19.9 | 157 | 19.7 | 169 | 21.2 | 153 | 19.2 | 159 | 20.0 | 0.93 | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 116 | 23.6 | 88 | 17.9 | 85 | 17.3 | 93 | 18.9 | 109 | 22.2 | 0.11 | |||||

| Any cause | 460 | 21.4 | 425 | 19.8 | 420 | 19.5 | 432 | 20.1 | 412 | 19.2 | 0.53 | |||||

| ESTHER (n = 3,566) | ||||||||||||||||

| Portion of study population | 713 | 20.0 | 713 | 20.0 | 712 | 20.0 | 712 | 20.0 | 716 | 20.0 | ||||||

| Age, yearsb | 62.3 (6.7) | 62.4 (6.4) | 62.3 (6.5) | 61.9 (6.4) | 60.5 (6.6) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Male sex | 367 | 18.6 | 373 | 18.9 | 381 | 19.3 | 407 | 20.6 | 449 | 22.7 | 0.02 | |||||

| Body mass index | 28.0 (4.6) | 27.6 (4.2) | 27.7 (4.3) | 27.8 (4.7) | 27.4 (4.1) | 0.16 | ||||||||||

| Current smoker | 140 | 22.2 | 121 | 19.2 | 126 | 20.0 | 124 | 19.7 | 120 | 19.0 | 0.72 | |||||

| Vigorous physical activityd | 300 | 20.1 | 299 | 20.0 | 300 | 20.1 | 297 | 19.9 | 299 | 20.0 | 1.00 | |||||

| Education, years | 9.5 (1.1) | 9.4 (1.0) | 9.4 (0.9) | 9.4 (1.0) | 9.4 (0.9) | 0.54 | ||||||||||

| Alcohol consumption, g/day | 11.4 (16.9) | 10.6 (13.6) | 10.2 (14.0) | 9.2 (11.7) | 9.2 (13.6) | 0.02 | ||||||||||

| Total cholesterol level, mmol/L | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.4 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.6) | 5.0 (1.6) | 5.1 (1.6) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 140.4 (18.7) | 140.2 (19.4) | 141.3 (20.6) | 140.8 (20.9) | 138.8 (19.2) | 0.18 | ||||||||||

| Chronic disease history | ||||||||||||||||

| Cancer | 48 | 20.8 | 43 | 18.6 | 45 | 19.5 | 45 | 19.5 | 50 | 21.7 | 0.95 | |||||

| Diabetes | 86 | 21.2 | 82 | 20.2 | 83 | 20.4 | 81 | 20.0 | 74 | 18.2 | 0.91 | |||||

| Coronary heart disease | 34 | 17.4 | 42 | 21.5 | 51 | 26.2 | 39 | 20.0 | 29 | 14.9 | 0.13 | |||||

| Stroke | 28 | 26.2 | 19 | 17.8 | 26 | 24.3 | 15 | 14.0 | 19 | 17.8 | 0.24 | |||||

| Mortality | ||||||||||||||||

| Cancer | 43 | 18.1 | 52 | 21.9 | 51 | 21.5 | 46 | 19.4 | 45 | 19.0 | 0.86 | |||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 34 | 17.1 | 37 | 18.6 | 44 | 22.1 | 41 | 20.6 | 43 | 21.6 | 0.78 | |||||

| Any cause | 100 | 16.2 | 135 | 21.8 | 127 | 20.5 | 133 | 21.5 | 124 | 20.0 | 0.17 | |||||

Abbreviations: ESTHER, Epidemiological Study on the Chances of Prevention, Early Recognition, and Optimized Treatment of Chronic Diseases in the Older Population; SE, standard error.

a Based on analysis of variance.

bz score was not adjusted for age.

c Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

d Any vigorous physical activity (>0 hours/week).

Results of the survival analyses from the individual cohorts are provided in Web Tables 2–4 for all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality, respectively. In both cohorts, the hazard ratios from the crude model (adjusted only for batch effect) showed an inverse association between LTL and all-cause mortality, with especially marked graded associations in ESTHER (Web Table 2). After additional adjustment for age, associations were clearly attenuated, but a significant inverse trend of telomere length with all-cause mortality was still observed in both cohorts. However, after adjustment for further covariates (models 3 and 4), the associations no longer reached statistical significance. Comparable patterns were observed for CVD and cancer mortality.

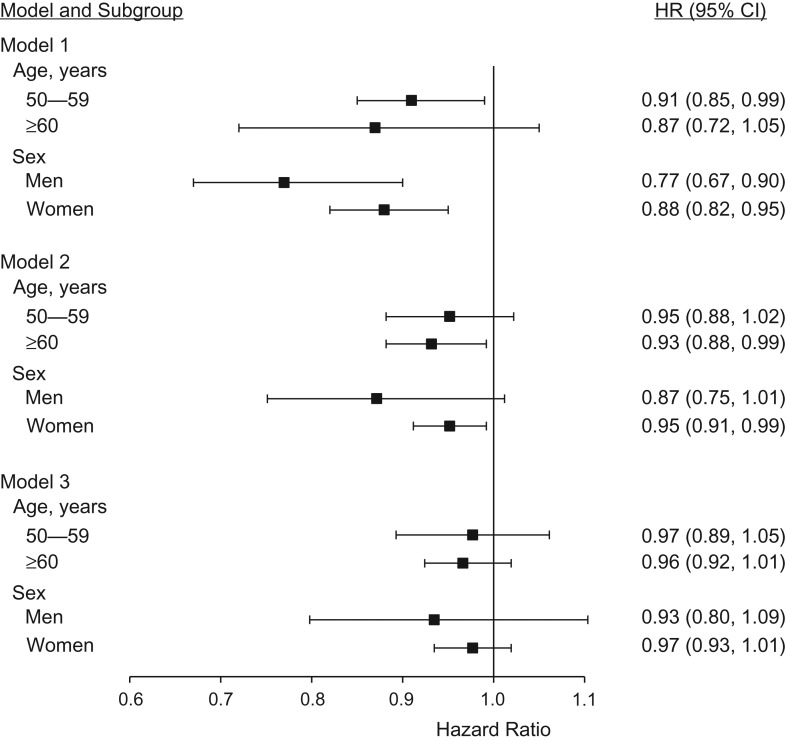

Results of the random-effects meta-analyses are summarized in Table 2 for the whole study population, and summary estimates from sex- and age-stratified models are shown in Figure 1. Looking at the z score quintiles, gradients were observed for all-cause, CVD, and cancer mortality in the crude model, and for all-cause mortality as well after age adjustment. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in the quintile with the shortest telomere length was 1.66 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.09, 2.53) in the crude model, 1.23 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.46) in the age-adjusted model, and 1.10 (95% CI: 0.97, 1.25) in the model adjusted for age and further covariates. The summary trend estimate for the association of the continuous z score with all-cause mortality was 0.82 (95% CI: 0.68, 0.99) in the crude model, indicating an 18% decrease in all-cause mortality per 1-standard-deviation increase in relative telomere length. After adjustment for age, the summary estimate was attenuated to 0.92 (95% CI: 0.85, 1.00; P = 0.052), and it was attenuated to 0.96 (95% CI: 0.93, 1.00; P = 0.065) after adjustment for further covariates. Again, patterns were similar for CVD mortality and cancer mortality overall, but no summary estimate from the random-effects meta-analyses reached statistical significance. No big differences across sex or age groups were seen in stratified models for the outcome all-cause mortality, but associations tended to be somewhat stronger in men and in persons aged 60 years or older (Figure 1). However, tests for interaction indicated no significant effect modification by age or sex for any outcome (details not shown).

Table 2.

Association of Leukocyte Telomere Length With Mortality (Random-Effects Meta-Analysis) in the Nurses’ Health Study (1989–2010) and ESTHER (2000–2015)

| Measure of Telomere Length | No. of Persons | No. of Cases | Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |||

| All-Cause Mortality | |||||||||||

| Quintile of z score | |||||||||||

| 1 (shortest) | 2,425 | 627 | 1.66 | 1.09, 2.53 | 0.018 | 1.23 | 1.04, 1.46 | 0.017 | 1.10 | 0.97, 1.25 | 0.156 |

| 2 | 2,462 | 616 | 1.50 | 0.96, 2.36 | 0.078 | 1.18 | 0.94, 1.48 | 0.151 | 1.10 | 0.88, 1.37 | 0.417 |

| 3 | 2,414 | 568 | 1.26 | 0.96, 1.66 | 0.098 | 1.06 | 0.94, 1.20 | 0.345 | 1.02 | 0.89, 1.17 | 0.810 |

| 4 | 2,470 | 572 | 1.17 | 1.02, 1.34 | 0.025 | 1.08 | 0.96, 1.22 | 0.219 | 1.06 | 0.93, 1.21 | 0.349 |

| 5 (longest) | 2,427 | 499 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | |||

| Continuous z score | 12,199 | 2,882 | 0.82 | 0.68, 0.99 | 0.043 | 0.92 | 0.85, 1.00 | 0.052 | 0.96 | 0.93, 1.00 | 0.065 |

| Dichotomized z score | |||||||||||

| <Median | 6,106 | 1,508 | 1.27 | 0.97, 1.67 | 0.081 | 1.10 | 0.94, 1.28 | 0.244 | 1.04 | 0.89, 1.21 | 0.629 |

| ≥Median | 6,093 | 1,374 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | |||

| Cardiovascular Disease Mortality | |||||||||||

| Quintile of z score | |||||||||||

| 1 (shortest) | 2,374 | 182 | 1.84 | 0.85, 3.97 | 0.120 | 1.29 | 0.83, 2.00 | 0.258 | 1.05 | 0.82, 1.34 | 0.707 |

| 2 | 2,411 | 153 | 1.38 | 0.62, 3.11 | 0.431 | 1.06 | 0.62, 1.81 | 0.825 | 0.93 | 0.60, 1.44 | 0.742 |

| 3 | 2,371 | 137 | 1.30 | 0.60, 2.82 | 0.501 | 1.08 | 0.62, 1.88 | 0.793 | 1.01 | 0.54, 1.90 | 0.967 |

| 4 | 2,415 | 152 | 1.26 | 0.84, 1.89 | 0.270 | 1.09 | 0.86, 1.39 | 0.486 | 1.03 | 0.76, 1.41 | 0.826 |

| 5 (longest) | 2,390 | 144 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | |||

| Continuous z score | 11,962 | 800 | 0.82 | 0.62, 1.08 | 0.153 | 0.94 | 0.81, 1.08 | 0.381 | 0.99 | 0.91, 1.08 | 0.844 |

| Dichotomized z score | |||||||||||

| <Median | 5,984 | 402 | 1.22 | 0.78, 1.90 | 0.379 | 1.02 | 0.76, 1.37 | 0.897 | 0.97 | 0.75, 1.25 | 0.813 |

| ≥Median | 5,978 | 398 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | |||

| Cancer Mortality | |||||||||||

| Quintile of z score | |||||||||||

| 1 (shortest) | 2,345 | 233 | 1.42 | 0.88, 2.27 | 0.149 | 1.10 | 0.88, 1.37 | 0.416 | 1.04 | 0.84, 1.27 | 0.736 |

| 2 | 2,370 | 225 | 1.27 | 0.85, 1.90 | 0.245 | 1.03 | 0.85, 1.26 | 0.744 | 1.01 | 0.77, 1.31 | 0.967 |

| 3 | 2,334 | 235 | 1.19 | 0.98, 1.44 | 0.077 | 1.10 | 0.91, 1.32 | 0.319 | 1.08 | 0.89, 1.33 | 0.425 |

| 4 | 2,375 | 211 | 1.05 | 0.87, 1.28 | 0.605 | 1.00 | 0.82, 1.22 | 0.994 | 1.01 | 0.82, 1.23 | 0.953 |

| 5 (longest) | 2,358 | 207 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | |||

| Continuous z score | 11,783 | 1,111 | 0.88 | 0.74, 1.05 | 0.164 | 0.98 | 0.92, 1.04 | 0.494 | 0.99 | 0.92, 1.06 | 0.764 |

| Dichotomized z score | |||||||||||

| <Median | 5,900 | 573 | 1.22 | 0.87, 1.73 | 0.251 | 1.09 | 0.85, 1.38 | 0.504 | 1.05 | 0.79, 1.40 | 0.718 |

| ≥Median | 5,883 | 538 | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | 1 | Referent | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ESTHER, Epidemiological Study on the Chances of Prevention, Early Recognition, and Optimized Treatment of Chronic Diseases in the Older Population; HR, hazard ratio.

a Crude model; results were adjusted only for batch effect (random effect).

b Results were additionally adjusted for age (and sex in ESTHER).

c Results were additionally adjusted for smoking status, body mass index, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and education.

Figure 1.

Association of leukocyte telomere length with all-cause mortality in the Nurses’ Health Study (1989–2010) and ESTHER (Epidemiological Study on the Chances of Prevention, Early Recognition, and Optimized Treatment of Chronic Diseases in the Older Population; 2000–2015), by age group and sex. Hazard ratios (HRs) represent summary estimates from meta-analyses, except those for men, which represent estimates for the male subgroup of ESTHER. Bars, 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results of fixed-effects meta-analyses are presented in Web Table 5, showing consistent associations which were somewhat attenuated but of higher precision. Heterogeneity was especially high for models with smaller numbers of covariates (details not shown), warranting the use of random-effects meta-analyses.

DISCUSSION

In this study, which included 12,199 adults with 2,882 deaths over a mean follow-up period of 16.7 years, LTL was significantly associated with all-cause mortality. After adjustment for age, the associations were clearly attenuated, but the quintile with the shortest LTL still showed significantly increased mortality hazards (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.46). Comparable patterns were seen for CVD and cancer mortality, but the summary estimates did not reach statistical significance. Mortality patterns were generally consistent across sex and age groups, but associations tended to be somewhat stronger among men and above the age of 60 years. Associations were stronger in the ESTHER study, which was smaller than the NHS but included both men and women and had a slightly narrower and older age range. Nevertheless, patterns were generally quite consistent across both cohorts.

In the present study, we observed that when adjusting for age, the association of LTL with mortality became attenuated, reflecting the association of age with all-cause mortality. However, even after age adjustment, the mortality hazard ratio for the shortest LTL quintile was still significantly increased, indicating a relationship beyond age. The associations were further attenuated after adjustment for lifestyle-related variables, possibly reflecting associations of lifestyle with mortality. However, even after these adjustments, LTL was still inversely and borderline-significantly associated with mortality (per 1-standard-deviation increment in LTL, HR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93, 1.00). Hence, we provide further evidence that LTL predicts mortality beyond its association with age and possibly also beyond associations with lifestyle, and thus could be an indicator of biological fitness in adults in the general population.

In the last decade, research on telomere biology and dynamics in populations has drawn substantial attention in medical and epidemiologic fields. While it is established that LTL shortens with age (4), results from studies investigating the association of LTL with health outcomes—as well as lifestyle-related factors, such as smoking, obesity, physical activity, and stress—have not been as definite (36–39). In most of the studies, investigators hypothesized that lifestyle and environmental factors that lead to heightened oxidative stress would lead to higher telomere attrition rates and hence shortened LTL, which would impair survival in the long run (40). However, the inconsistent results obtained from highly heterogeneous studies suggest that telomere dynamics might be rather more complex than initially thought. There are multiple factors contributing to this heterogeneity, and limitations of measurement methods are especially important. The LTL measurement methods used showed substantial heterogeneity between the studies, impairing the comparability of study findings.

There was also large variation in the size and age range of previous studies assessing the association between LTL and mortality. Whereas some earlier, relatively small studies had found a strong inverse association between LTL and mortality (17, 41, 42), a much weaker association or no association at all was seen in a number of larger, mostly more recent studies (11–13, 25, 26, 43). However, in the largest study conducted so far, a Danish study with 64,637 participants and 7,607 deaths compiled during 22 years of follow-up, linear graded associations and modestly increased hazards for the shortest deciles of LTL versus the longest deciles were seen for all-cause mortality (HR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.25, 1.57), CVD mortality (HR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.66), and cancer mortality (HR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.65) (27). Our study confirms these findings in a meta-analysis of data from 2 large prospective cohort studies from Germany and the United States. Even though not all summary estimates reached statistical significance in our study (especially after multivariate adjustment and for cancer and CVD mortality), possibly due to the smaller sample size, the mortality patterns were quite consistent with those of the Danish study.

Interestingly, 2 recent US studies noted racial differences in the association of LTL with mortality. In a study of postmenopausal women, Carty et al. (43) found a significant association of the shortest LTL quartile with increased all-cause and CVD mortality in white women but no association in African-American women. In contrast, in a study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Needham et al. (11) found a strong association between LTL and CVD mortality only among African-American participants. Because both cohorts in the present study consisted mostly of white participants, we were not able to study ethnic differences. However, our findings support an association of LTL with mortality among white Europeans and Americans.

Our study had specific strengths and limitations. Since the relative LTL data were derived from different cohorts, we calculated z scores to be able to pool data together and carry out meta-analysis. As a result, only the magnitudes of the associations could be shown, and the corresponding T/S ratios or absolute LTL, in base pairs, could not be quantified. As in any observational study, measurement error in self-reported variables is inevitable. Although the analyses were controlled for multiple covariates which could possibly act as confounders, the possibility of residual confounding remains. The LTL measurement yielded acceptable, but not excellent, coefficients of variation for the quality control samples which were in the usual range reported in the literature. This variation may render it more difficult to detect true associations. Then again, high correlation coefficients achieved between the terminal restriction fragment analysis, which is regarded as the gold standard, and quantitative PCR measurements document the quality of LTL measurements in the ESTHER study. The large sample size and >10-year follow-up times in both studies makes this study one of the largest carried out in the field thus far. The inclusion of 2 independent cohorts from Europe and the United States suggests broad generalizability of our results to older white populations. Although there was also some heterogeneity in data collection across the studies, this heterogeneity was minimized by major data harmonization efforts, which is not commonly possible in meta-analyses of published data.

Altogether, our findings support previous evidence suggesting that LTL predicts all-cause mortality even beyond its association with age and that it could also be inversely associated with CVD and cancer mortality. Hence, LTL could serve as an indicator of biological fitness in the general population.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany (Ute Mons, Aysel Müezzinler, Ben Schöttker, Aida Karina Dieffenbach, Katja Butterbach, Hermann Brenner); Network Aging Research, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany (Aysel Müezzinler, Ben Schöttker, Hermann Brenner); German Cancer Consortium, Heidelberg, Germany (Aida Karina Dieffenbach, Hermann Brenner); Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany (Matthias Schick); Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Faculty of Population Health Sciences, University College London, London, United Kingdom (Anne Peasey); Channing Laboratory, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Immaculata De Vivo); Program in Genetic Epidemiology and Statistical Genetics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts (Immaculata De Vivo); Hellenic Health Foundation, Athens, Greece (Antonia Trichopoulou, Paolo Boffetta); Department of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Medical School, University of Athens, Athens, Greece (Antonia Trichopoulou); and Institute for Translational Epidemiology and Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York (Paolo Boffetta).

U.M. and A.M. contributed equally to this work.

Data used throughout the present study were derived from the CHANCES project. The project was coordinated by the Hellenic Health Foundation, Athens, Greece. The project was supported by the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development of the Directorate-General for Research and Innovation of the European Commission (grant agreement HEALTH-F3-2010-242244). The Nurses’ Health Study is supported by the National Cancer Institute, US National Institutes of Health (grants 1R01 CA134958, 2R01 CA082838, P01 CA087969, R01 CA49449, CA065725, CA132190, CA139586, CA140790, CA133914, CA132175, CA163451, HL088521, HL60712, U54 CA155626, R01 AR059073, and HL34594). The ESTHER study is funded in part by grants from the Baden Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Arts and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. The work of A.M. was supported by a scholarship from the Klaus Tschira Foundation.

The study sponsors played no role in the study design, data collection, analyses, or interpretation of results, the preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lansdorp PM, Verwoerd NP, van de Rijke FM, et al. Heterogeneity in telomere length of human chromosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5(5):685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martens UM, Zijlmans JM, Poon SS, et al. Short telomeres on human chromosome 17p. Nat Genet. 1998;18(1):76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mather KA, Jorm AF, Parslow RA, et al. Is telomere length a biomarker of aging? A review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(2):202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Müezzinler A, Zaineddin AK, Brenner H. A systematic review of leukocyte telomere length and age in adults. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olovnikov AM. Principle of marginotomy in template synthesis of polynucleotides [in Russian]. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1971;201(6):1496–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blackburn EH. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature. 2000;408(6808):53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brouilette S, Singh RK, Thompson JR, et al. White cell telomere length and risk of premature myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(5):842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Farzaneh-Far R, Cawthon RM, Na B, et al. Prognostic value of leukocyte telomere length in patients with stable coronary artery disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(7):1379–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Gardner JP, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Cawthon RM, et al. Short telomere length, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and early death. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(3):822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Needham BL, Rehkopf D, Adler N, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and mortality in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Epidemiology. 2015;26(4):528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Svensson J, Karlsson MK, Ljunggren Ö, et al. Leukocyte telomere length is not associated with mortality in older men. Exp Gerontol. 2014;57:6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Kimura M, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and mortality in the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(4):421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma H, Zhou Z, Wei S, et al. Shortened telomere length is associated with increased risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Prescott J, Wentzensen IM, Savage SA, et al. Epidemiologic evidence for a role of telomere dysfunction in cancer etiology. Mutat Res. 2012;730(1-2):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wentzensen IM, Mirabello L, Pfeiffer RM, et al. The association of telomere length and cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(6):1238–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Willeit P, Willeit J, Kloss-Brandstätter A, et al. Fifteen-year follow-up of association between telomere length and incident cancer and cancer mortality. JAMA. 2011;306(1):42–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Willeit P, Willeit J, Mayr A, et al. Telomere length and risk of incident cancer and cancer mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(1):69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fu X, Wan S, Hann HW, et al. Relative telomere length: a novel non-invasive biomarker for the risk of non-cirrhotic hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(7):1014–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han J, Qureshi AA, Prescott J, et al. A prospective study of telomere length and the risk of skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(2):415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lan Q, Cawthon R, Shen M, et al. A prospective study of telomere length measured by monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7429–7433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lynch SM, Major JM, Cawthon R, et al. A prospective analysis of telomere length and pancreatic cancer in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer (ATBC) Prevention Study. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(11):2672–2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanchez-Espiridion B, Chen M, Chang JY, et al. Telomere length in peripheral blood leukocytes and lung cancer risk: a large case-control study in Caucasians. Cancer Res. 2014;74(9):2476–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xie H, Wu X, Wang S, et al. Long telomeres in peripheral blood leukocytes are associated with an increased risk of soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 2013;119(10):1885–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bendix L, Thinggaard M, Fenger M, et al. Longitudinal changes in leukocyte telomere length and mortality in humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(2):231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Telomere shortening unrelated to smoking, body weight, physical activity, and alcohol intake: 4,576 general population individuals with repeat measurements 10 years apart. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rode L, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Peripheral blood leukocyte telomere length and mortality among 64,637 individuals from the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boffetta P, Bobak M, Borsch-Supan A, et al. The Consortium on Health and Ageing: Network of Cohorts in Europe and the United States (CHANCES) project—design, population and data harmonization of a large-scale, international study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(12):929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prescott J, Du M, Wong JY, et al. Paternal age at birth is associated with offspring leukocyte telomere length in the Nurses’ Health Study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3622–3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(10):e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Figueroa R, Lindenmaier H, Hergenhahn M, et al. Telomere erosion varies during in vitro aging of normal human fibroblasts from young and adult donors. Cancer Res. 2000;60(11):2770–2774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kimura M, Hjelmborg JV, Gardner JP, et al. Telomere length and mortality: a study of leukocytes in elderly Danish twins. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(7):799–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rehm J, Room R, Monteiro M, et al. Alcohol use In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, et al., eds. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attribution to Selected Major Risk Factors. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004:959–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Normand SL. Meta-analysis: formulating, evaluating, combining, and reporting. Stat Med. 1999;18(3):321–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwarzer G. Package ‘meta’: General Package for Meta-Analysis. Version 4.8-1. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/meta/meta.pdf. Published March 17, 2015. Accessed April 11, 2017.

- 36. Cassidy A, De Vivo I, Liu Y, et al. Associations between diet, lifestyle factors, and telomere length in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1273–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Müezzinler A, Mons U, Dieffenbach AK, et al. Smoking habits and leukocyte telomere length dynamics among older adults: results from the ESTHER cohort. Exp Gerontol. 2015;70:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Müezzinler A, Zaineddin AK, Brenner H. Body mass index and leukocyte telomere length in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15(3):192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhu H, Wang X, Gutin B, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in healthy Caucasian and African-American adolescents: relationships with race, sex, adiposity, adipokines, and physical activity. J Pediatr. 2011;158(2):215–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. von Zglinicki T. Role of oxidative stress in telomere length regulation and replicative senescence. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;908:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O'Brien E, et al. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet. 2003;361(9355):393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ehrlenbach S, Willeit P, Kiechl S, et al. Influences on the reduction of relative telomere length over 10 years in the population-based Bruneck Study: introduction of a well-controlled high-throughput assay. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1725–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carty CL, Kooperberg C, Liu J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and risks of incident coronary heart disease and mortality in a racially diverse population of postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(10):2225–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.