Abstract

Overexpression of the Aurora-A (AURKA) kinase is oncogenic in many tumors. Many studies of AURKA have focused on activities of this kinase in mitosis, and elucidated the mechanisms by which AURKA activity is induced at the G2/M boundary through interactions with proteins such as TPX2 and NEDD9. These studies have informed the development of small molecule inhibitors of AURKA, of which a number are currently under preclinical and clinical assessment. While the first activities defined for AURKA were its control of centrosomal maturation and organization of the mitotic spindle, an increasing number of studies over the past decade have recognized a separate biological function of AURKA, in controlling disassembly of the primary cilium, a small organelle protruding from the cell surface that serves as a signaling platform. Importantly, these activities require activation of AURKA in early G1, and the mechanisms of activation are much less well defined than those in mitosis. Better understanding of the control of AURKA activity, and the role of AURKA at cilia, are both important in optimizing the efficacy and interpreting potential downstream consequences of AURKA inhibitors in the clinic. We here provide a current overview of proteins and mechanisms that have been defined as activating AURKA in G1, based on study of ciliary disassembly.

Keywords: Cilium, AURKA, serine/threonine kinase, human malignancy, ciliopathy, signal transduction

Introduction

More than 20 years ago, a serine/threonine kinase required for correct spindle formation was identified in Drosophila and named “aurora” based on the phenotype of dispersed and asymmetric astral microtubules found in hypomorphic mutants [1]. This was the first characterized member of a kinase family that regulates mitotic events including spindle assembly and cytokinesis, and pre-mitotic events including centrosomal maturation. These activities require the cyclic, strong activation of the kinase in late G2 and its inactivation at mitotic completion [2]. Aurora kinases are evolutionally highly conserved from yeast to mammals [3]. The single family member in Drosophila has three paralogs in humans - Aurora kinase A (AURKA), which localizes to the centrosome and radial microtubules [4], Aurora kinase B (AURKB), and Aurora kinase C (AURKC) – with AURKA maintaining the centrosomal and spindle functions initially described in flies, and AURKB and AURKC fulfilling other roles [2]. In addition to its role in mitosis, AURKA has been reported to regulate stem cell differentiation, self-renewal and reprogramming [5, 6]. Reflecting these essential roles, oncogenic defects in regulation of AURKA are frequently noted in cancer. AURKA is frequently amplified or overexpressed in numerous malignancies, including but not limiting to breast cancer, leukemia, bladder, ovarian, gastric, esophageal, liver, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers [7-14]. Because of this role in cancer, AURKA is in the focus of development of drugs that block its activation by various mechanisms [4, 15] that have been defined based on studies of the protein in mitosis [16-19].

In contrast to the general focus on AURKA in mitosis, an increasing number of studies have documented an additional role of AURKA. This role reflects non-mitotic functions at the ciliary basal body, a structure that differentiates from the centrosome in non-proliferating, post-mitotic cells [20]. The growing literature on AURKA regulation at cilia suggests additional mechanisms for the control of AURKA activity than those previously identified through studies of AURKA activation in mitosis, which may be relevant to its action in cancer and other pathologic conditions. These alternative mechanisms of AURKA regulation are the focus of this review.

As general introduction, cilia fall into two categories: motile and immotile (or primary) cilia. Motile cilia have many features in common with the flagella of single cell eukaryotes [21], and are found in a limited number of cell types in vertebrates [22]. However, single primary cilia, are present on virtually all cell types in vertebrates (with several notable exceptions, e.g. hematopoietic cell lineage have typically been considered as constitutively non-ciliated, although a recent study has called even this exclusion into question [23]). Primary cilia are expressed from the earliest stages of organismal development, contributing to appropriate pattern formation [24], and are retained in adult tissue. The primary cilium is an organelle organized around a microtubule-based axoneme nucleated at the ciliary basal body, which protrudes from the cell surface and acts as an antenna sensing and transducing various extracellular signals. Although first discovered at the end of 19th century [25], the function of the primary cilium was long obscure, with this structure initially hypothesized to act as a dock for centrosomes in non-mitotic cells [26]. However, over the past two decades, a large number of studies have unveiled the critical regulatory functions for primary cilium, emphasizing its importance in developmental biology and many human diseases.

The primary cilium is now known to provide a spatially concentrated platform for receipt of extracellular cues and induction of intracellular response for signaling pathways downstream of Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) [27], WNT [28, 29], Notch [30], PDGFRα [31], polycystins (PC1 [32] and PC2 [33]) and others. Activity of these pathways depends in large part on the presence or absence of a primary cilium on the cell surface. Some pathogenic conditions, described below, are associated with constitutive changes in cilia, because of dysfunctional structure or chronic loss. However, an intriguing feature of the cilium, long-known but poorly understood, is the fact that it undergoes regular protrusion and resorption that is coordinated with cell cycle [34]. Typically, cells are ciliated in quiescent G0 and early G1 cells, and invariably, cells lack cilia during mitosis. In most cells, resorption occurs in G1, as cells are induced to active cycling [35]. While the mechanics of the reassembly process have been established to require changes in the action of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) machinery [36, 37], exact details of the disassembly mechanism remain to be elucidated.

In 2007, AURKA was first identified as a proximal regulator of disassembly and resorption of primary cilia [38], an activity paralleling that of its distant orthologue, CALK, in regulating disassembly of motile flagella in the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii [39]. As impairments in the assembly, maintenance and disassembly of the primary cilium are positioned to impact all the cilia-dependent signaling networks, these findings spawned intensive subsequent study. As a consequence of this work, many new mechanisms for activation of AURKA in non-mitotic cells have been suggested. These connections may also be extremely relevant to the role of AURKA in cancer and other pathogenic conditions, and suggest additional ways to target the kinase, as we discuss here.

Assembly and Disassembly Control of AURKA activation

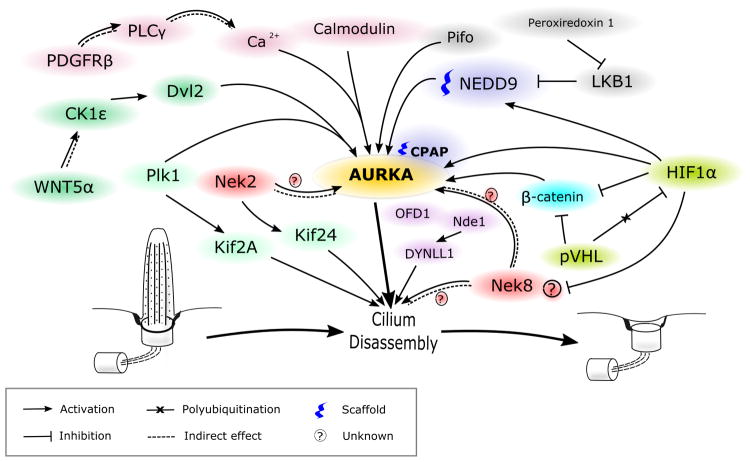

Our emphasis in this review is on signaling pathways that impinge directly or indirectly on control of AURKA activity (Figure 1, 2). Proteomic studies of the primary cilium have identified hundreds of proteins associated with this organelle, many of which have been implicated in regulating or mediating the processes of ciliogenesis and ciliary resorption [40-43]. Sanchez and Dynlacht have provided a recent comprehensive review of these processes [44]. Studies addressing the mechanisms regulating assembly and disassembly typically identify Aurora A (AURKA) as a proximal component of the disassembly machinery, activated by interaction with a group of directly interacting partner proteins, and sometimes implicating its interactions with a tubulin deacetylase, HDAC6 [38] (Figure 1). More recently, other components of cilia disassembly mechanism have been defined, including signaling from PLK1 – another kinase best known for function in mitosis – and the microtubule-associated kinesin motor KIF2A [45], the NEK2 kinase with an alternative kinesin, KIF24 [46], and other pathways (e.g., NEK8 [47, 48]). For PLK1 and NEK8, potential mechanisms for crosstalk with AURKA have been shown. The more recently proposed NEK2 pathway has been suggested to be completely independent, although due to limited state of current knowledge, AURKA involvement cannot be completely excluded.

Figure 1. Scheme of signaling pathways, regulating AURKA activity during ciliary disassembly.

See description in text.

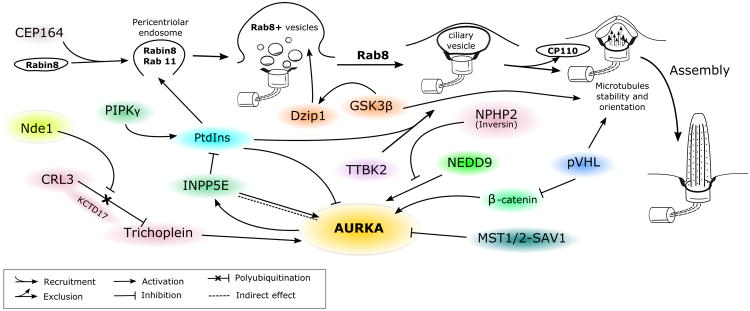

Figure 2. Scheme, representing role of AURKA in ciliogenesis.

See description in text.

Activation of AURKA during ciliary disassembly

1. AURKA proximal signaling

An unexpected non-mitotic role of AURKA in promoting ciliary disassembly was first shown by Pugacheva et al. [38]. They observed that the levels of T288-auto-phosphorylated AURKA and of its activator, the scaffolding protein NEDD9 [49], significantly increased at 1-2h and 18-24h after stimulating starved, quiescent cells with serum to induce cell cycle re-entry. These activation dynamics strongly correlated with the percentage of ciliated cells; and while the 18-24 hour peak represented G2/M, and a known time of AURKA activation and ciliary resorption, the 1-2 hour peak reflected cells in G1 phase. Moreover, siRNA knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of AURKA completely blocked serum-induced ciliary disassembly, while NEDD9 knockdown greatly limited disassembly. To provide stronger evidence for a ciliary role of AURKA, they performed microinjections of preactivated wild type AURKA, hypomorphic mutant AURKA, and inactive mutant AURKA into cells, and observed an extremely rapid deciliation with preactivated AURKA, a modest decrease in ciliation for the hypomorphic mutant, and no phenotype with inactive mutant AURKA. This study identified HDAC6 as a candidate downstream effector of AURKA, showing pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 blocked ciliary disassembly, and finding that microinjection of preactivated AURKA into cells with siRNA-depleted HDAC6 caused delayed and unstable deciliation, with the majority of disassembled cilia reconstituted in 1 hour. They also showed that AURKA interacts with and specifically phosphorylates HDAC6 enhancing its activity. Connecting these data, the authors proposed that upregulation of NEDD9 promoted transient, AURKA autophosphorylation, which allowed AURKA-dependent activation of HDAC6; active HDAC6 deacetylated microtubules in the ciliary axoneme, contributing to its destabilization [38]. Interestingly, a reverse process of polymerized α-tubulin K40 acetylation by theαTAT1 acetyltransferase, a highly conserved protein among organisms assembling cilia, was subsequently shown to significantly promote ciliogenesis [50].

Adding to this initial outline of AURKA regulation, Kinzel et al. determined that mutations in the ciliary gene Pitchfork (Pifo) led to ciliary defects and left-right asymmetry abnormalities during development [51]. Pifo, a little-studied small (191 aa) protein with no defined sequence motifs, which has been implicated in Hedgehog signaling [52], colocalizes with AURKA at the ciliary base and directly interacts with AURKA in pulldown assays. Overexpression of Pifo in cells resulted in higher level of phosphorylated AURKA during ciliary disassembly, and a longer duration of AURKA activation. Conversely, overexpression of R80K-mutated Pifo (identified as a heterozygous mutation in two cases of ciliopathy-associated phenotype in human patients [51]) completely abolished AURKA activation while having no impact on protein stability or AURKA interaction. Interestingly, the observed accumulation of Pifo at ciliary base was cell cycle dependent, with the highest levels present during early assembly or disassembly of primary cilia. In addition to enhancing AURKA activity, Pifo also has been found important for preventing centrosome overreplication during S phase; additional roles are under investigation.

Inoko and colleagues reported that Trichoplein (TCHP), originally identified as a keratin filament binding scaffold protein [53], co-localized with AURKA at centrioles, and showed that it interacted with and promoted activation of centriolar AURKA, thus explaining its role as a negative regulator of ciliogenesis [54]. Extending the TCHP signaling network, Inaba et al. showed that NDEL1, an NDE1 paralog, supports trichoplein expression by protecting it from proteasomal degradation, suppressing axonemal extension [55]. NDE1, a member of nuclear distribution E (NudE) protein family, been found to act as a negative regulator of ciliary length, possibly through its interaction with the dynein-containing DYNLL1/LC8, which is associated with retrograde IFT components [56]. In a recent study of radial glia precursors using in vivo shRNA-mediated gene knockdown [57], only depletion of NDE1 significantly increased ciliary length, while knockdown of either NDE1 or NDEL1 resulted in cell cycle block (G2/M and G1/S arrest for NDE1 and NDEL1 respectively). Interestingly, double knockdown of these two proteins caused an exacerbated G1/S block, suggesting dominance of the NDEL1 phenotype. Whether NDE1 directly controls TCHP is not yet known.

Beyond NEDD9, other proteins have been proposed to contribute to scaffolding AURKA activation and for ciliary regulation. Centrosomal-P4.1-associated protein (CPAP), mutated in microcephaly-associated Seckel syndrome, was found to interact and possibly serve as a scaffold for a ciliary disassembly complex comprised of NDE1, AURKA, HDAC6 and another protein, Oral-facial-digital syndrome 1 protein (OFD1) [58]. Neural progenitor cells with CPAP knockdown exhibited excessively long cilia, delayed cell-cycle re-entry and premature differentiation. The mechanism by which CPAP influences AURKA activation has not been investigated.

There is increasing evidence for a role for calcium signaling in regulation of AURKA activation in disassembly of the primary cilium. Plotnikova et al. showed that calmodulin directly interacts with the N-terminus of AURKA in a calcium-dependent manner, resulting in AURKA autophosphorylation of S51, S53/S54, S66/S67 or S98, and demonstrated that this interaction is required for serum-induced cilia disassembly and mitotic progression [59, 60]. Inducible over-expression of S51A-, S53A/S54A-, or S66A/S67A-mutated AURKA derivatives in a wild type AURKA-depleted background failed to restore serum induced ciliary disassembly, in comparison to reconstitution with wild type AURKA. These data add a suggestion of mechanism to an increasing number of studies emphasizing the importance of the AURKA N-terminus, which is is required for AURKA centrosomal localization [61], interaction with its activator NEDD9 [49, 62] and regulation of its proteosomal degradation after mitosis [63].

An upstream pathway for calcium signaling as mediator of some stimuli for ciliary resorption was subsequently identified by Nielsen and colleagues [64], who found that PDGF-DD-induced deciliation occurs through direct PDGFRβ binding and activation of PLCγ. This triggered calcium release from internal stores and subsequent AURKA activation. In the same study, expression of a constitutively active PDGFRα D842V mutant, which had increased affinity for binding PLCγ instead of the preferred effectors of WT PDGFRα (MEK1/2-ERK1/2 and AKT), led to a significant loss of cilia. This was reversed by pharmacological inhibition of AURKA or PDGFRα, emphasizing the important role of PLCγ in AURKA activation and ciliary resorption. Both these studies [59, 64] confirmed that forced release of calcium from intracellular storage by ionophore ionomycin led to rapid loss of primary cilia.

Plotnikova et al. showed a complex interaction between inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E (INPP5E), a protein defective in some ciliopathies, and AURKA that influenced ciliary resorption. AURKA and INPP5E signaling was bidirectional. INPP5E promoted AURKA autophosphorylation, most likely by producing phosphatidyl inositol-(PtdIns)-(3,4)-diphosphate, which facilitated AURKA activation. Their conclusion was based in part on data indicating that co-expression of INPP4B (a phosphatase decreasing the levels of PtdIns(3,4)P2) with AURKA and INPP5E in HEK293 cells significantly decreased the level of T288-auto-phosphorylated AURKA. In turn, AURKA phosphorylation of INPP5E increased its phosphatase activity and thus production of PtdIns(3,4)P2 forming a short positive feedback loop. More indirectly, increased hydrolysis of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, led to a negative feedback loop that decreased AURKA transcription [65].

Lee and colleagues identified a new signaling cascade for ciliary disassembly in which non-canonical WNT pathway activation caused Plk1-dependent stabilization of the direct AURKA activator NEDD9 [66]. They first identified the WNT-pathway effector Disheveled-2 (Dvl2) as a PLK1-binding protein, and with this interaction mediated by two casein kinases able to phosphorylate Dvl2 to create a binding site for Plk1, CK1δ and CK1ε. Among the two, only CK1ε knockdown led to impaired ciliary disassembly. Treatment of cells with conditioned media enriched with Wnt5α, a WNT superfamily member activating non-canonical WNT pathway signaling and CK1ε, significantly increased the levels of phospho-Dvl2 (S143 and T224), increased the formation of Dvl2-Plk1 complexes in a CK1ε-dependent manner. Subsequently, the Dvl2-Plk1 complex bound the NEDD9-interacting protein SMAD3, preventing it from targeting NEDD9 for degradation, and hence indirectly promoting AURKA activation. Extending this signaling axis, Shnitsar et al. showed that the phosphatase PTEN, an extensively studied tumor suppressor [67, 68], also can contribute to ciliary dynamics regulation by dephosphorylating Dvl2 at S143 and thus acting as a negative regulator of the previously described signaling pathway [69].

Besides its interaction with Dvl2, PLK1 has been implicated in interactions with a kinesin, KIF2A, that also converge with AURKA activation control. Miyamoto et al. conducted an extensive study characterizing Plk1-Kif2A pathway promoting ciliary disassembly, in which PLK1 phosphorylation on T544 of Kif2A activated this kinesin to promote microtubule disassembly in vitro, although a detailed mechanism is yet to be elucidated [45, 70]. In separate work, Jang et al. have studied AURKA and PLK1 in mitosis during spindle formation, and have shown these proteins act antagonistically in regulation of Kif2A, with AURKA decreasing depolymerization activity of Kif2A [71]. Whether similar actions occur in feedback during ciliary disassembly, is unknown.

In more indirect regulation of AURKA, Gong et al. have linked Peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1), an enzyme that reduces reactive oxygen species, to regulation of the primary cilium [72]. They showed that esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines expressing high levels of peroxiredoxin had suppressed cilia formation, while ciliation was restored by shRNA knockdown of peroxiredoxin shRNA-knockdown. They suggested that peroxiredoxin suppresses cilia formation by activating AURKA through an LKB1/AMPK pathway. LKB1 has been reported to inhibit the AURKA activator NEDD9 [73], and the authors showed that shRNA knockdown of peroxiredoxin 1 led to increased levels of LKB1 and hyper-phosphorylated AMPK, but decreased T288-phosphorylated AURKA levels.

Nek2-Kif24 pathway

The kinase Nek2 also contributes to ciliary disassembly [46]. Nek2 localizes to the proximal region of centriole throughout cell cycle, but preferentially expands localization profile to include the distal region of the mother centriole during the S/G2 phases of the cell cycle. Nek2 interacts and directly phosphorylates the kinesin Kif24, increasing its microtubule depolymerizing activity, and contributing to ciliary resorption, with most of this activity observed during G2/M phase [46, 74]. While this mechanism has been validated for pre-mitotic ciliary resorption, it has not been shown to contribute to G0/G1 resorption events, which have been shown to be regulated by AURKA-HDAC6 and Plk1-Kif2A. Although no intersection between this pathway and AURKA activation controls have yet been described, this pathway was only recently detected, and connections may emerge. For example, in a study by Pugacheva et al. it has been shown that NEDD9 not only is able to activate AURKA but also inhibits NEK2 activity; however, a possible relationship between AURKA and NEK2 was not explored [49].

In the kidney epithelium, formation of primary cilium is regulated by the VHL protein, that itself localizes to the primary cilium. VHL interacts with GSK-3β and directly interacts with microtubules, supporting the stabilization and orientation that is crucial for maintaining the ciliary axoneme [75-77]. VHL is a tumor suppressor, polyubiquitin-ligase that normally targets various proteins including HIF1α for degradation, and is commonly lost in kidney cancers. Ding et al. have shown that Nek8 is transcriptionally upregulated by loss of the ciliary stabilization factor pVHL in human renal cancer cell lines and speculated that Nek8 might play role in ciliary disassembly [47], although a connection to AURKA is not yet apparent. Dere and colleagues [78] identified a different mechanism for control of cilia in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) through transcriptional upregulation of the AURKA protein. This study found that in pVHL-deficient ccRCC cell lines, AURKA upregulation is driven by β-catenin-regulated transcription; while the increased HIF1α activity in these cells partially inhibits β-catenin, the net effect is an AURKA increase. These studies revealed a complex dualistic role of pVHL in regulating primary cilia.

Nek8 and others

NEK8 (never in mitosis A-related kinase 8) has been recently suggested to have a function at cilia. In a study by Otto et al. several mutations in NEK8 gene were found in patients with nephronophthisis and some of them decreased its ciliary (L336F and H413Y) or centrosomal (H425Y) localization, although the Nek8 role on ciliogenesis and ciliary disassembly was not investigated [79]. It was also shown that defects in Nek8 ciliary localization might promote cystogenesis in kidneys [80] possibly through its influence on expression and localization of the polycystins PC1 and PC2 [81]. Zalli and colleagues have shown that Nek8 localizes at cilia and is degraded upon cells entering a quiescent state; however, although overall protein levels decrease, T162-phosphorylated (activated) Nek8 accumulates during cell cycle exit [82]. Grampa et al. found that mutations in Nek8 genes are associated with severe renal cystic dysplasia phenotype in human patients and in mouse models, in which Nek8 influences ciliogenesis and cell cycle, possibly through regulation of the nucleocytoplasmic shuttle of YAP, a main Hippo pathway effector. Interestingly, while Nek8 shRNA knockdown or overexpression of wild type Nek8 did not affect ciliogenesis, overexpression of cystic renal dysplasia-associated mutants of Nek8 (G580S and R602W) resulted in significant loss of cilia in cultured cells [48]. In patient fibroblasts with such mutants, there was increased YAP activation and nuclear localization. Interestingly, zebrafish embryos injected with either wild type or mutant Nek8 RNA exhibited a ciliopathy phenotype: an increased proportion of ventrally or dorsally curved body axis as well as laterality defects and pronephros abnormalities (cysts) and that phenotype was significantly restored by treatment with verteporfin, a YAP suppressor [83]. It will be of interest to determine if NEK8 functions to control AURKA activation.

Restriction of AURKA activity during ciliary assembly

After mitosis is complete, ciliogenesis occurs (Figure 2): this process has been thoroughly reviewed [84]. In brief introduction to the process of ciliogenesis to provide context for studies of AURKA activity control, immediately after mitosis, a group of distal appendage proteins (DAPs) that associate with the mother centriole, including Cep83, Cep89, Cep164, SCLT1 and FBF1, contribute to docking of post-mitotic centrioles to the membrane. The centriole differentiates to a basal body, anchoring primary cilium formation [85]. In cycling cells, the centriolar protein CP110 mechanistically forms a cap at the distal region of centrioles preventing axoneme extension. During ciliary assembly, a critical early event is the exclusion of CP110 from centrioles, which is required for axoneme formation [86]. While little is currently known about the exact mechanism of this molecular event or its upstream regulators, two kinases, Tau tubulin kinase 2 (TTBK2) [87] and microtubule affinity regulating kinase 4 (MARK4) [88] contribute to this process by phosphorylating one or more of components of the CP110/Cep97/Cep290/Kif24 ciliary assembly inhibitory complex. Interestingly, TTBK2 recruitment was shown to be dependent on PtdIns level that is being regulated by PIPKγ and INPP5E that, respectively, promote and inhibit TTBK2 recruitment to centriole, CP110 exclusion and thus ciliogenesis [89].

In parallel, Cep164 recruits Rabin8, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and the Rab8 GTPase to a pericentriolar vesicle [90], where the Rab11 GTPase stimulates the nucleotide exchange activity of Rabin8 [91], subsequently causing the activation and accumulation of Rab8 and primary ciliary vesicle formation [92, 93]. In parallel, PI3K Class II α (PI3K-C2α) co-localizes with Rab11 at the ciliary base, and produces 3-phosphorylated phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns) that are required for Rab11 activation and subsequent Rab8 accumulation at ciliary base [94]. An additional component, the zinc-finger-containing protein Dzip1 supports Rab8 accumulation and activation at basal body [95]. Moreover, Dzip1 requires phosphorylation by GSK-3β for activity in recruiting Rab8. Together, these proteins function to target specific proteins that are important for its function as a signaling hub through a ciliary transition zone and into the ciliary membrane.

Although AURKA levels are reduced after mitosis [96], a residual pool of the protein remains located at the ciliary basal body. Ciliary assembly requires this pool of AURKA remain inactive. Inactivity is assured in part by lack of signaling partners that promote AURKA activation. For example, NEDD9, a major AURKA activator, has been shown to accumulate at the centrosome during G2/M phase, but be expressed at a very low level in this intracellular compartment throughout the rest of cell cycle, except for a transient peak during specific induction of disassembly [49]. The AURKA activator Pifo also accumulates at centrosomes only at specific stages of the cell cycle – during early ciliary assembly, to prevent premature formation of cilium and during disassembly to facilitate it [51].

In part, inactivity of AURKA is achieved through the activity of proteins that negatively regulate AURKA. For example, Mergen et al. have shown that Inversin (NPHP2), a protein mutated in the ciliopathy nephronophthisis, can directly interact with both AURKA and its activator NEDD9, thus preventing AURKA activation at ciliary base [97]. An active process regulates the disappearance of trichoplein/TCHP specifically from the mother centriole but not the daughter centriole at the beginning of ciliogenesis; as the mother centriole is the source of the nascent basal body of an assembling cilium, this suggested a potentially important regulatory role. Kasahara et al. demonstrated that this phenomenon occurs due to polyubiquitination of trichoplein by Cul3-RING E3 ligase (CRL3)–KCTD17 complex (CRL3KCTD17) targeting it to proteosomal degradation [98]. Prior to primary cilium formation, trichoplein is targeted to degradation by CRL3KCTD17 ubiquitin-proteasome system releasing inhibitory effect of AURKA on primary cilium assembly [98].

The Hippo/YAP pathway is important for regulating contact inhibition and actin remodeling: in cultured cells, this process promotes ciliary assembly [99]. Interestingly, two major Hippo pathway components, the kinases MST1 and MST2, together with an activating scaffolding protein, SAV1, were shown to co-localize at ciliary base, and promote ciliogenesis. Kim and colleagues found that these MST kinases phosphorylate AURKA preferentially on serines of N-terminal fragment (although the exact sites were not identified), and that this phosphorylation disrupts AURKA-HDAC6 association and formation of ciliary disassembly complex. In parallel, MST1/2 proteins promote ciliary assembly through their association with NPHP proteins to regulating trafficking of various cargos through the ciliary transition zone, including Rab8a, Smo and RPGR [100].

AURKA, ciliopathies and cancer

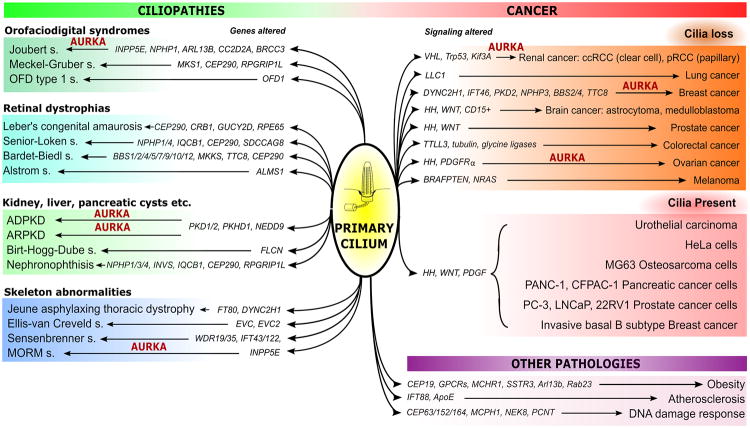

Mutations in genes encoding proteins required for ciliogenesis have been identified as causal for a large number of genetic disorders that are classified as ciliopathies, with some of these directly connected to regulation of AURKA activity (Figure 3). Ciliopathies are typically hereditary syndromes with defects of primary cilia, and are associated with a wide range of overlapping symptoms. Several recent reviews elucidate the relationship between cilia and these pathologies [101-103]. One of the most studied ciliopathiesis autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), which is the fourth leading cause of renal failure worldwide in adults and affects approximately 1 in 400 people [104, 105]. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) is the second common hereditary kidney disorder, more widespread among children [106, 107]. Birt-Hogg-Dube (BHD) syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder where patients are predisposed to kidney cancer, lung and kidney cysts and benign skin tumors [108]. Less common ciliopathies are some of the oral-facial-digital (OFD) syndromes, such as Joubert syndrome, Meckel-Gruber syndrome and orofaciodigital syndrome type 1 [109-113]. Other ciliopathies include, but are not limited to retinal dystrophies, such as Leber's congenital amaurosis [114], Senior–Løken syndrome [115], Bardet–Biedl syndrome [116, 117], Alström syndrome [118] and other types of nephronophthisis [119]. Ciliary disorders of the skeleton are found in Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy [119, 120], Ellisvan Creveld syndrome, Sensen-Brenner syndrome (cranioectodermal dysplasia) and several others [121]. Some ciliary proteins contribute to regulation of metabolism and vascular development, with dysfunctions in components of the ciliary proteome leading to an increased risk of obesity [122-124] and predispose to the development of atherosclerotic plaques [125, 126].

Figure 3. Ciliary defects in ciliopathies and cancer.

Schematically represented summary of alterations in different genes and signaling pathways (highlighted in italic) affecting the primary cilium that lead to development of the diseases indicated. AURKA is highlighted in red, when there is published evidence of its involvement. Pathologies are clustered into three groups: ciliopathies (grouped by most common distinguished feature), cancer (with presence and loss of cilia reported), and other pathologies. Abbreviations: VHL – Von Hippel-Lindau, HH – Hedgehog signaling.

Pathological activation of AURKA has been observed for some of the ciliopathies, with particular focus on studies in ADPKD, the most common and most studied ciliopathy REFs. The non-mitotic activation of AURKA was observed in pre-clinical models of ADPKD, where it was shown to be regulated by Ca2+/CaM binding [59]. Further, misregulation of AURKA and its direct activator NEDD9 were shown to play important roles in promoting cystogenesis in a murine model of ADPKD [127]. In this study, the authors observed that in mice genetically null for NEDD9, a major AURKA activator, exhibited multiple abnormalities in cilia, including elongated cilia and multiciliated cells. Interestingly, when combined with conditional PKD1 knockout, a NEDD9 null genotype significantly exacerbated the cystic phenotype, although NEDD9 null mice did not generate cysts in the absence of a PKD1 driver lesion [127]. Similar findings also were observed after administration of AURKA inhibitors in PKD1 mutant mice, therefore suggesting caution in use of these agents in management of ADPKD and cancer therapies [127, 128]. In addition, mutations in INPP5E [65] cause the ciliopathies known as Joubert [129] and MORM (mental retardation, truncal obesity, retinal dystrophy and micropenis) syndromes [130]. Thereby, over the last decade multiple studies have revealed a direct link between additional non-mitotic AURKA functions including control of ciliary stability and calcium signaling and ciliopathies.

A growing number of studies and reviews have addressed the topic of possible connections between ciliary dynamics and cancer. Cilia are lost in many types of cancer, leading to the idea that they may contribute to cell division checkpoints (although they are retained in some tumor types, such as medulloblastomas, basal cell carcinomas and epithelial ovarian carcinomas which are often dependent on Hedgehog (HH) signaling. Thus, Egeberg and colleagues demonstrated, that ciliogenesis in ovarian tumors might be impaired due to overexpression of AURKA, leading to aberrant HH signaling [131]. In addition, some linkages have been identified between ciliogenesis and the cancer-relevant process of DNA damage response (DDR) regulation [132]. An extended discussion of this field is beyond the scope of this article, with several reviews recently published on this topic [133-135]. However, in specific relationship to control of AURKA, a well-known hallmark of clear cell renal carcinoma (ccRCC) is loss of the primary cilium, driven by loss of VHL gene and increased AURKA/HDAC6 activities [78]; while overexpression of the AURKA activator NEDD9 is common and promotes metastasis in many cancers [136], which may be linked in part to loss of cilia.

Conclusions

The data summarized above emphasize the multiple mechanisms for control of AURKA in non-mitotic cells, identified through study of ciliary dynamics. These include activation by Pifo, NEDD9, calmodulin, trichoplein, HIF1α, Plk1, β-catenin, and Dvl2, and inhibition by NPHP2, PtdIns, MST1/2-SAV1. For many of these mechanisms, including regulation by Pifo, trichoplein, Nde1, CPAP, and the Nek2-Kif24 pathway, Nek8, their relevance to mitotic activation of AURKA is essentially unknown, and requires investigation. Some studies of AURKA small molecule inhibitors, including some under investigation as cancer therapeutics, have shown that interaction of AURKA with specific mitotic activation partners such as NEDD9 or TPX2 influence the activity of inhibitors [137, 138]. For more recently defined ciliary partners, whether these agents affect activity profile of inhibitors requires further study. It is also possible that drugs targeting AURKA might exhibit unanticipated adverse effects from cilia stabilization in both normal and malignant cells. Given the rapid increase in studies demonstrating importance of the primary cilium in cell differentiation, proliferation, stem cell status, and other processes, it may be useful to include assessment of ciliary effects for drugs targeting AURKA and related partner proteins.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by NIH R01 DK108195 (to EAG); by the Russian Government Program for Competitive Growth of Kazan Federal University (to AD); and by NIH Core Grant CA006927 (to Fox Chase Cancer Center).

References

- 1.Glover DM, Leibowitz MH, McLean DA, Parry H. Mutations in aurora prevent centrosome separation leading to the formation of monopolar spindles. Cell. 1995;81:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. The cellular geography of aurora kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:842–854. doi: 10.1038/nrm1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown JR, Koretke KK, Birkeland ML, Sanseau P, Patrick DR. Evolutionary relationships of Aurora kinases: implications for model organism studies and the development of anti-cancer drugs. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bischoff JR, Anderson L, Zhu Y, Mossie K, Ng L, Souza B, Schryver B, Flanagan P, Clairvoyant F, Ginther C, Chan CS, Novotny M, Slamon DJ, Plowman GD. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Z, Rana TM. A kinase inhibitor screen identifies small-molecule enhancers of reprogramming and iPS cell generation. Nature communications. 2012;3:1085. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee DF, Su J, Ang YS, Carvajal-Vergara X, Mulero-Navarro S, Pereira CF, Gingold J, Wang HL, Zhao R, Sevilla A, Darr H, Williamson AJ, Chang B, Niu X, Aguilo F, Flores ER, Sher YP, Hung MC, Whetton AD, Gelb BD, Moore KA, Snoeck HW, Ma'ayan A, Schaniel C, Lemischka IR. Regulation of embryonic and induced pluripotency by aurora kinase-p53 signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ochi T, Fujiwara H, Yasukawa M. Aurora-A kinase: a novel target both for cellular immunotherapy and molecular target therapy against human leukemia. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1399–1410. doi: 10.1517/14728220903307483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park HS, Park WS, Bondaruk J, Tanaka N, Katayama H, Lee S, Spiess PE, Steinberg JR, Wang Z, Katz RL, Dinney C, Elias KJ, Lotan Y, Naeem RC, Baggerly K, Sen S, Grossman HB, Czerniak B. Quantitation of Aurora kinase A gene copy number in urine sediments and bladder cancer detection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1401–1411. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka T, Kimura M, Matsunaga K, Fukada D, Mori H, Okano Y. Centrosomal kinase AIK1 is overexpressed in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast. Cancer research. 1999;59:2041–2044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe T, Imoto I, Katahira T, Hirasawa A, Ishiwata I, Emi M, Takayama M, Sato A, Inazawa J. Differentially regulated genes as putative targets of amplifications at 20q in ovarian cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:1114–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Zhu J, Firozi PF, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, Cleary K, Friess H, Sen S. Overexpression of oncogenic STK15/BTAK/Aurora A kinase in human pancreatic cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:991–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamada K, Yamada Y, Hirao T, Fujimoto H, Takahama Y, Ueno M, Takayama T, Naito A, Hirao S, Nakajima Y. Amplification/overexpression of Aurora-A in human gastric carcinoma: potential role in differentiated type gastric carcinogenesis. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:593–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rojanala S, Han H, Munoz RM, Browne W, Nagle R, Von Hoff DD, Bearss DJ. The mitotic serine threonine kinase, Aurora-2, is a potential target for drug development in human pancreatic cancer. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2004;3:451–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cammareri P, Scopelliti A, Todaro M, Eterno V, Francescangeli F, Moyer MP, Agrusa A, Dieli F, Zeuner A, Stassi G. Aurora-a is essential for the tumorigenic capacity and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells. Cancer research. 2010;70:4655–4665. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HH, Zhu Y, Govindasamy KM, Gopalan G. Downregulation of Aurora-A overrides estrogen-mediated growth and chemoresistance in breast cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:765–775. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Zhou YX, Qiao W, Tominaga Y, Ouchi M, Ouchi T, Deng CX. Overexpression of aurora kinase A in mouse mammary epithelium induces genetic instability preceding mammary tumor formation. Oncogene. 2006;25:7148–7158. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou H, Kuang J, Zhong L, Kuo WL, Gray JW, Sahin A, Brinkley BR, Sen S. Tumour amplified kinase STK15/BTAK induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy and transformation. Nature genetics. 1998;20:189–193. doi: 10.1038/2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorgun G, Calabrese E, Hideshima T, Ecsedy J, Perrone G, Mani M, Ikeda H, Bianchi G, Hu Y, Cirstea D, Santo L, Tai YT, Nahar S, Zheng M, Bandi M, Carrasco RD, Raje N, Munshi N, Richardson P, Anderson KC. A novel Aurora-A kinase inhibitor MLN8237 induces cytotoxicity and cell-cycle arrest in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;115:5202–5213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huck JJ, Zhang M, McDonald A, Bowman D, Hoar KM, Stringer B, Ecsedy J, Manfredi MG, Hyer ML. MLN8054, an inhibitor of Aurora A kinase, induces senescence in human tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2010;8:373–384. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikonova AS, Astsaturov I, Serebriiskii IG, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Golemis EA. Aurora A kinase (AURKA) in normal and pathological cell division. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2013;70:661–687. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margulis L. Undulipodia, flagella and cilia. Biosystems. 1980;12:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(80)90041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewin B. Cells. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury; Mass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh M, Chaudhry P, Merchant AA. Primary Cilia are Present on Human Blood and Bone Marrow Cells and Mediate Hedgehog Signaling. Exp Hematol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bangs FK, Schrode N, Hadjantonakis AK, Anderson KV. Lineage specificity of primary cilia in the mouse embryo. Nature cell biology. 2015;17:113–122. doi: 10.1038/ncb3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowalevsky AO. Entwickelungsgeschichte des Amphioxus lanceolatus. Eggers: St.-Pétersbourg; 1867. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorokin S. Centrioles and the formation of rudimentary cilia by fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. The Journal of cell biology. 1962;15:363–377. doi: 10.1083/jcb.15.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong SY, Seol AD, So PL, Ermilov AN, Bichakjian CK, Epstein EH, Jr, Dlugosz AA, Reiter JF. Primary cilia can both mediate and suppress Hedgehog pathway-dependent tumorigenesis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/nm.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suizu F, Hirata N, Kimura K, Edamura T, Tanaka T, Ishigaki S, Donia T, Noguchi H, Iwanaga T, Noguchi M. Phosphorylation-dependent Akt-Inversin interaction at the basal body of primary cilia. EMBO J. 2016;35:1346–1363. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Kronig C, Schermer B, Benzing T, Cabello OA, Jenny A, Mlodzik M, Polok B, Driever W, Obara T, Walz G. Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2005;37:537–543. doi: 10.1038/ng1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ezratty EJ, Stokes N, Chai S, Shah AS, Williams SE, Fuchs E. A role for the primary cilium in Notch signaling and epidermal differentiation during skin development. Cell. 2011;145:1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clement DL, Mally S, Stock C, Lethan M, Satir P, Schwab A, Pedersen SF, Christensen ST. PDGFRalpha signaling in the primary cilium regulates NHE1-dependent fibroblast migration via coordinated differential activity of MEK1/2-ERK1/2-p90RSK and AKT signaling pathways. Journal of cell science. 2013;126:953–965. doi: 10.1242/jcs.116426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hou X, Mrug M, Yoder BK, Lefkowitz EJ, Kremmidiotis G, D'Eustachio P, Beier DR, Guay-Woodford LM. Cystin, a novel cilia-associated protein, is disrupted in the cpk mouse model of polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:533–540. doi: 10.1172/JCI14099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pazour GJ, San Agustin JT, Follit JA, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Polycystin-2 localizes to kidney cilia and the ciliary level is elevated in orpk mice with polycystic kidney disease. Current biology : CB. 2002;12:R378–380. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00877-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorokin SP. Centriole formation and ciliogenesis. Vol. 11. Aspen; Emphysema Conf: 1968. pp. 213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Archer FL, Wheatley DN. Cilia in cell-cultured fibroblasts. II. Incidence in mitotic and post-mitotic BHK 21-C13 fibroblasts. J Anat. 1971;109:277–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Witman GB. The DHC1b (DHC2) isoform of cytoplasmic dynein is required for flagellar assembly. The Journal of cell biology. 1999;144:473–481. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Vucica Y, Seeley ES, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB, Cole DG. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;151:709–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pugacheva EN, Jablonski SA, Hartman TR, Henske EP, Golemis EA. HEF1-dependent Aurora A activation induces disassembly of the primary cilium. Cell. 2007;129:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan J, Snell WJ. Regulated targeting of a protein kinase into an intact flagellum. An aurora/Ipl1p-like protein kinase translocates from the cell body into the flagella during gamete activation in chlamydomonas. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:24106–24114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002686200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis EE, Brueckner M, Katsanis N. The emerging complexity of the vertebrate cilium: new functional roles for an ancient organelle. Dev Cell. 2006;11:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marshall WF. Basal bodies platforms for building cilia. Current topics in developmental biology. 2008;85:1–22. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ostrowski LE, Dutcher SK, Lo CW. Cilia and models for studying structure and function. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2011;8:423–429. doi: 10.1513/pats.201103-027SD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan S, Sun Z. Expanding horizons: ciliary proteins reach beyond cilia. Annual review of genetics. 2013;47:353–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez I, Dynlacht BD. Cilium assembly and disassembly. Nature cell biology. 2016;18:711–717. doi: 10.1038/ncb3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto T, Hosoba K, Ochiai H, Royba E, Izumi H, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Dynlacht BD, Matsuura S. The Microtubule-Depolymerizing Activity of a Mitotic Kinesin Protein KIF2A Drives Primary Cilia Disassembly Coupled with Cell Proliferation. Cell reports. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S, Lee K, Choi JH, Ringstad N, Dynlacht BD. Nek2 activation of Kif24 ensures cilium disassembly during the cell cycle. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8087. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding XF, Zhou J, Hu QY, Liu SC, Chen G. The tumor suppressor pVHL down-regulates never-in-mitosis A-related kinase 8 via hypoxia-inducible factors to maintain cilia in human renal cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290:1389–1394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.589226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grampa V, Delous M, Zaidan M, Odye G, Thomas S, Elkhartoufi N, Filhol E, Niel O, Silbermann F, Lebreton C, Collardeau-Frachon S, Rouvet I, Alessandri JL, Devisme L, Dieux-Coeslier A, Cordier MP, Capri Y, Khung-Savatovsky S, Sigaudy S, Salomon R, Antignac C, Gubler MC, Benmerah A, Terzi F, Attie-Bitach T, Jeanpierre C, Saunier S. Novel NEK8 Mutations Cause Severe Syndromic Renal Cystic Dysplasia through YAP Dysregulation. PLoS genetics. 2016;12:e1005894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pugacheva EN, Golemis EA. The focal adhesion scaffolding protein HEF1 regulates activation of the Aurora-A and Nek2 kinases at the centrosome. Nature cell biology. 2005;7:937–946. doi: 10.1038/ncb1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shida T, Cueva JG, Xu Z, Goodman MB, Nachury MV. The major alpha-tubulin K40 acetyltransferase alphaTAT1 promotes rapid ciliogenesis and efficient mechanosensation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:21517–21522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013728107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinzel D, Boldt K, Davis EE, Burtscher I, Trumbach D, Diplas B, Attie-Bitach T, Wurst W, Katsanis N, Ueffing M, Lickert H. Pitchfork regulates primary cilia disassembly and left-right asymmetry. Dev Cell. 2010;19:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung B, Padula D, Burtscher I, Landerer C, Lutter D, Theis F, Messias AC, Geerlof A, Sattler M, Kremmer E, Boldt K, Ueffing M, Lickert H. Pitchfork and Gprasp2 Target Smoothened to the Primary Cilium for Hedgehog Pathway Activation. PloS one. 2016;11:e0149477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishizawa M, Izawa I, Inoko A, Hayashi Y, Nagata K, Yokoyama T, Usukura J, Inagaki M. Identification of trichoplein, a novel keratin filament-binding protein. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:1081–1090. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inoko A, Matsuyama M, Goto H, Ohmuro-Matsuyama Y, Hayashi Y, Enomoto M, Ibi M, Urano T, Yonemura S, Kiyono T, Izawa I, Inagaki M. Trichoplein and Aurora A block aberrant primary cilia assembly in proliferating cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;197:391–405. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inaba H, Goto H, Kasahara K, Kumamoto K, Yonemura S, Inoko A, Yamano S, Wanibuchi H, He D, Goshima N, Kiyono T, Hirotsune S, Inagaki M. Ndel1 suppresses ciliogenesis in proliferating cells by regulating the trichoplein-Aurora A pathway. The Journal of cell biology. 2016;212:409–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201507046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim S, Zaghloul NA, Bubenshchikova E, Oh EC, Rankin S, Katsanis N, Obara T, Tsiokas L. Nde1-mediated inhibition of ciliogenesis affects cell cycle re-entry. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:351–360. doi: 10.1038/ncb2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doobin DJ, Kemal S, Dantas TJ, Vallee RB. Severe NDE1-mediated microcephaly results from neural progenitor cell cycle arrests at multiple specific stages. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12551. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gabriel E, Wason A, Ramani A, Gooi LM, Keller P, Pozniakovsky A, Poser I, Noack F, Telugu NS, Calegari F, Saric T, Hescheler J, Hyman AA, Gottardo M, Callaini G, Alkuraya FS, Gopalakrishnan J. CPAP promotes timely cilium disassembly to maintain neural progenitor pool. EMBO J. 2016;35:803–819. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plotnikova OV, Nikonova AS, Loskutov YV, Kozyulina PY, Pugacheva EN, Golemis EA. Calmodulin activation of Aurora-A kinase (AURKA) is required during ciliary disassembly and in mitosis. Molecular biology of the cell. 2012;23:2658–2670. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plotnikova OV, Pugacheva EN, Dunbrack RL, Golemis EA. Rapid calcium-dependent activation of Aurora-A kinase. Nat Commun. 2010;1:64. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giet R, Prigent C. The non-catalytic domain of the Xenopus laevis auroraA kinase localises the protein to the centrosome. Journal of cell science. 2001;114:2095–2104. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.11.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pugacheva EN, Golemis EA. HEF1-aurora A interactions: points of dialog between the cell cycle and cell attachment signaling networks. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:384–391. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.4.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Littlepage LE, Ruderman JV. Identification of a new APC/C recognition domain, the A box, which is required for the Cdh1-dependent destruction of the kinase Aurora-A during mitotic exit. Genes & development. 2002;16:2274–2285. doi: 10.1101/gad.1007302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen BS, Malinda RR, Schmid FM, Pedersen SF, Christensen ST, Pedersen LB. PDGFRbeta and oncogenic mutant PDGFRalpha D842V promote disassembly of primary cilia through a PLCgamma- and AURKA-dependent mechanism. Journal of cell science. 2015;128:3543–3549. doi: 10.1242/jcs.173559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Plotnikova OV, Seo S, Cottle DL, Conduit S, Hakim S, Dyson JM, Mitchell CA, Smyth IM. INPP5E interacts with AURKA, linking phosphoinositide signaling to primary cilium stability. Journal of cell science. 2015;128:364–372. doi: 10.1242/jcs.161323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee KH, Johmura Y, Yu LR, Park JE, Gao Y, Bang JK, Zhou M, Veenstra TD, Yeon Kim B, Lee KS. Identification of a novel Wnt5a-CK1varepsilon-Dvl2-Plk1-mediated primary cilia disassembly pathway. EMBO J. 2012;31:3104–3117. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Milella M, Falcone I, Conciatori F, Cesta Incani U, Del Curatolo A, Inzerilli N, Nuzzo CM, Vaccaro V, Vari S, Cognetti F, Ciuffreda L. PTEN: Multiple Functions in Human Malignant Tumors. Front Oncol. 2015;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tesio M, Trinquand A, Macintyre E, Asnafi V. Oncogenic PTEN functions and models in T-cell malignancies. Oncogene. 2016;35:3887–3896. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shnitsar I, Bashkurov M, Masson GR, Ogunjimi AA, Mosessian S, Cabeza EA, Hirsch CL, Trcka D, Gish G, Jiao J, Wu H, Winklbauer R, Williams RL, Pelletier L, Wrana JL, Barrios-Rodiles M. PTEN regulates cilia through Dishevelled. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8388. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ochiai H, Miyamoto T, Kanai A, Hosoba K, Sakuma T, Kudo Y, Asami K, Ogawa A, Watanabe A, Kajii T, Yamamoto T, Matsuura S. TALEN-mediated single-base-pair editing identification of an intergenic mutation upstream of BUB1B as causative of PCS (MVA) syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:1461–1466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317008111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jang CY, Coppinger JA, Seki A, Yates JR, 3rd, Fang G. Plk1 and Aurora A regulate the depolymerase activity and the cellular localization of Kif2a. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:1334–1341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.044321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gong F, Liu H, Li J, Xue L, Zhang M. Peroxiredoxin 1 is involved in disassembly of flagella and cilia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;444:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ji H, Ramsey MR, Hayes DN, Fan C, McNamara K, Kozlowski P, Torrice C, Wu MC, Shimamura T, Perera SA, Liang MC, Cai D, Naumov GN, Bao L, Contreras CM, Li D, Chen L, Krishnamurthy J, Koivunen J, Chirieac LR, Padera RF, Bronson RT, Lindeman NI, Christiani DC, Lin X, Shapiro GI, Janne PA, Johnson BE, Meyerson M, Kwiatkowski DJ, Castrillon DH, Bardeesy N, Sharpless NE, Wong KK. LKB1 modulates lung cancer differentiation and metastasis. Nature. 2007;448:807–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Spalluto C, Wilson DI, Hearn T. Nek2 localises to the distal portion of the mother centriole/basal body and is required for timely cilium disassembly at the G2/M transition. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:675–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Esteban MA. Formation of Primary Cilia in the Renal Epithelium Is Regulated by the von Hippel-Lindau Tumor Suppressor Protein. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17:1801–1806. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kuehn EW, Walz G, Benzing T. Von hippel-lindau: a tumor suppressor links microtubules to ciliogenesis and cancer development. Cancer research. 2007;67:4537–4540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lutz MS, Burk RD. Primary cilium formation requires von hippel-lindau gene function in renal-derived cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:6903–6907. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dere R, Perkins AL, Bawa-Khalfe T, Jonasch D, Walker CL. beta-catenin links von Hippel-Lindau to aurora kinase A and loss of primary cilia in renal cell carcinoma. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:553–564. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013090984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Otto EA, Trapp ML, Schultheiss UT, Helou J, Quarmby LM, Hildebrandt F. NEK8 mutations affect ciliary and centrosomal localization and may cause nephronophthisis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:587–592. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007040490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trapp ML, Galtseva A, Manning DK, Beier DR, Rosenblum ND, Quarmby LM. Defects in ciliary localization of Nek8 is associated with cystogenesis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0692-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sohara E, Luo Y, Zhang J, Manning DK, Beier DR, Zhou J. Nek8 regulates the expression and localization of polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:469–476. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zalli D, Bayliss R, Fry AM. The Nek8 protein kinase, mutated in the human cystic kidney disease nephronophthisis, is both activated and degraded during ciliogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1155–1171. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu-Chittenden Y, Huang B, Shim JS, Chen Q, Lee SJ, Anders RA, Liu JO, Pan D. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes & development. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Izawa I, Goto H, Kasahara K, Inagaki M. Current topics of functional links between primary cilia and cell cycle. Cilia. 2015;4:12. doi: 10.1186/s13630-015-0021-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tanos BE, Yang HJ, Soni R, Wang WJ, Macaluso FP, Asara JM, Tsou MFB. Centriole distal appendages promote membrane docking, leading to cilia initiation. Genes & development. 2013;27:163–168. doi: 10.1101/gad.207043.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kobayashi T, Tsang WY, Li J, Lane W, Dynlacht BD. Centriolar kinesin Kif24 interacts with CP110 to remodel microtubules and regulate ciliogenesis. Cell. 2011;145:914–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goetz SC, Liem KF, Jr, Anderson KV. The spinocerebellar ataxia-associated gene Tau tubulin kinase 2 controls the initiation of ciliogenesis. Cell. 2012;151:847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuhns S, Schmidt KN, Reymann J, Gilbert DF, Neuner A, Hub B, Carvalho R, Wiedemann P, Zentgraf H, Erfle H, Klingmuller U, Boutros M, Pereira G. The microtubule affinity regulating kinase MARK4 promotes axoneme extension during early ciliogenesis. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;200:505–522. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201206013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Xu Q, Zhang Y, Wei Q, Huang Y, Hu J, Ling K. Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase PIPKIgamma and phosphatase INPP5E coordinate initiation of ciliogenesis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10777. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmidt KN, Kuhns S, Neuner A, Hub B, Zentgraf H, Pereira G. Cep164 mediates vesicular docking to the mother centriole during early steps of ciliogenesis. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;199:1083–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Knodler A, Feng S, Zhang J, Zhang X, Das A, Peranen J, Guo W. Coordination of Rab8 and Rab11 in primary ciliogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6346–6351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002401107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoshimura S, Egerer J, Fuchs E, Haas AK, Barr FA. Functional dissection of Rab GTPases involved in primary cilium formation. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;178:363–369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Westlake CJ, Baye LM, Nachury MV, Wright KJ, Ervin KE, Phu L, Chalouni C, Beck JS, Kirkpatrick DS, Slusarski DC, Sheffield VC, Scheller RH, Jackson PK. Primary cilia membrane assembly is initiated by Rab11 and transport protein particle II (TRAPPII) complex-dependent trafficking of Rabin8 to the centrosome. roceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2759–2764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018823108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Franco I, Gulluni F, Campa CC, Costa C, Margaria JP, Ciraolo E, Martini M, Monteyne D, De Luca E, Germena G, Posor Y, Maffucci T, Marengo S, Haucke V, Falasca M, Perez-Morga D, Boletta A, Merlo GR, Hirsch E. PI3K class II alpha controls spatially restricted endosomal PtdIns3P and Rab11 activation to promote primary cilium function. Dev Cell. 2014;28:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang B, Zhang T, Wang G, Wang G, Chi W, Jiang Q, Zhang C. GSK3beta-Dzip1-Rab8 cascade regulates ciliogenesis after mitosis. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Walter AO, Seghezzi W, Korver W, Sheung J, Lees E. The mitotic serine/threonine kinase Aurora2/AIK is regulated by phosphorylation and degradation. Oncogene. 2000;19:4906–4916. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mergen M, Engel C, Muller B, Follo M, Schafer T, Jung M, Walz G. The nephronophthisis gene product NPHP2/Inversin interacts with Aurora A and interferes with HDAC6-mediated cilia disassembly. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2744–2753. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kasahara K, Kawakami Y, Kiyono T, Yonemura S, Kawamura Y, Era S, Matsuzaki F, Goshima N, Inagaki M. Ubiquitin-proteasome system controls ciliogenesis at the initial step of axoneme extension. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5081. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim J, Jo H, Hong H, Kim MH, Kim JM, Lee JK, Heo WD, Kim J. Actin remodelling factors control ciliogenesis by regulating YAP/TAZ activity and vesicle trafficking. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6781. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim M, Kim M, Lee MS, Kim CH, Lim DS. The MST1/2-SAV1 complex of the Hippo pathway promotes ciliogenesis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5370. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brown JM, Witman GB. Cilia and Diseases. Bioscience. 2014;64:1126–1137. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Habbig S, Liebau MC. Ciliopathies - from rare inherited cystic kidney diseases to basic cellular function. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2015;2:8. doi: 10.1186/s40348-015-0019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Waters AM, Beales PL. Ciliopathies: an expanding disease spectrum. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 2011;26:1039–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1731-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Igarashi P, Somlo S. Genetics and pathogenesis of polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002;13:2384–2398. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000028643.17901.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney international. 2009;76:149–168. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Deltas C, Papagregoriou G. Cystic diseases of the kidney: molecular biology and genetics. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2010;134:569–582. doi: 10.5858/134.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gunay-Aygun M. Liver and kidney disease in ciliopathies. American journal of medical genetics Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2009;151C:296–306. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luijten MN, Basten SG, Claessens T, Vernooij M, Scott CL, Janssen R, Easton JA, Kamps MA, Vreeburg M, Broers JL, van Geel M, Menko FH, Harbottle RP, Nookala RK, Tee AR, Land SC, Giles RH, Coull BJ, van Steensel MA. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome is a novel ciliopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4383–4397. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Barker AR, Thomas R, Dawe HR. Meckel-Gruber syndrome and the role of primary cilia in kidney, skeleton, and central nervous system development. Organogenesis. 2014;10:96–107. doi: 10.4161/org.27375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ben-Salem S, Al-Shamsi AM, Gleeson JG, Ali BR, Al-Gazali L. Mutation spectrum of Joubert syndrome and related disorders among Arabs. Human genome variation. 2014;1:14020. doi: 10.1038/hgv.2014.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Franco B, Thauvin-Robinet C. Update on oral-facial-digital syndromes (OFDS) Cilia. 2016;5:12. doi: 10.1186/s13630-016-0034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sattar S, Gleeson JG. The ciliopathies in neuronal development: a clinical approach to investigation of Joubert syndrome and Joubert syndrome-related disorders. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2011;53:793–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schock EN, Chang CF, Youngworth IA, Davey MG, Delany ME, Brugmann SA. Utilizing the chicken as an animal model for human craniofacial ciliopathies. Dev Biol. 2016;415:326–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Riaz M, Baird PN. Genetics in Retinal Diseases. Developments in ophthalmology. 2016;55:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000431142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ronquillo CC, Bernstein PS, Baehr W. Senior-Loken syndrome: a syndromic form of retinal dystrophy associated with nephronophthisis. Vision research. 2012;75:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Khan SA, Muhammad N, Khan MA, Kamal A, Rehman ZU, Khan S. Genetics of human Bardet-Biedl syndrome, an updates. Clinical genetics. 2016;90:3–15. doi: 10.1111/cge.12737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Suspitsin EN, Imyanitov EN. Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. Molecular syndromology. 2016;7:62–71. doi: 10.1159/000445491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Alvarez-Satta M, Castro-Sanchez S, Valverde D. Alstrom syndrome: current perspectives. The application of clinical genetics. 2015;8:171–179. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S56612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stokman M, Lilien M, Knoers N. Nephronophthisis. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, Bird TD, Fong CT, Mefford HC, Smith RJH, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews(R) University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle WA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Keppler-Noreuil KM, Adam MP, Welch J, Muilenburg A, Willing MC. Clinical insights gained from eight new cases and review of reported cases with Jeune syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy) American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2011;155A:1021–1032. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huber C, Cormier-Daire V. Ciliary disorder of the skeleton. American journal of medical genetics Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2012;160C:165–174. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mariman EC, Vink RG, Roumans NJ, Bouwman FG, Stumpel CT, Aller EE, van Baak MA, Wang P. The cilium: a cellular antenna with an influence on obesity risk. The British journal of nutrition. 2016;116:576–592. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516002282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lee H, Song J, Jung JH, Ko HW. Primary cilia in energy balance signaling and metabolic disorder. BMB Reports. 2015;48:647–654. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.12.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shalata A, Ramirez MC, Desnick RJ, Priedigkeit N, Buettner C, Lindtner C, Mahroum M, Abdul-Ghani M, Dong F, Arar N, Camacho-Vanegas O, Zhang R, Camacho SC, Chen Y, Ibdah M, DeFronzo R, Gillespie V, Kelley K, Dynlacht BD, Kim S, Glucksman MJ, Borochowitz ZU, Martignetti JA. Morbid obesity resulting from inactivation of the ciliary protein CEP19 in humans and mice. American journal of human genetics. 2013;93:1061–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dinsmore C, Reiter JF. Endothelial primary cilia inhibit atherosclerosis. EMBO reports. 2016;17:156–166. doi: 10.15252/embr.201541019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Willemarck N, Rysman E, Brusselmans K, Van Imschoot G, Vanderhoydonc F, Moerloose K, Lerut E, Verhoeven G, van Roy F, Vleminckx K, Swinnen JV. Aberrant activation of fatty acid synthesis suppresses primary cilium formation and distorts tissue development. Cancer research. 2010;70:9453–9462. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nikonova AS, Plotnikova OV, Serzhanova V, Efimov A, Bogush I, Cai KQ, Hensley HH, Egleston BL, Klein-Szanto A, Seeger-Nukpezah T, Golemis EA. Nedd9 restrains renal cystogenesis in Pkd1-/- mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:12859–12864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405362111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nikonova AS, Deneka AY, Eckman L, Kopp MC, Hensley HH, Egleston BL, Golemis EA. Opposing Effects of Inhibitors of Aurora-A and EGFR in Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Frontiers in oncology. 2015;5:228. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hampshire DJ, Ayub M, Springell K, Roberts E, Jafri H, Rashid Y, Bond J, Riley JH, Woods CG. MORM syndrome (mental retardation, truncal obesity, retinal dystrophy and micropenis), a new autosomal recessive disorder, links to 9q34. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:543–548. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Egeberg DL, Lethan M, Manguso R, Schneider L, Awan A, Jorgensen TS, Byskov AG, Pedersen LB, Christensen ST. Primary cilia and aberrant cell signaling in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cilia. 2012;1:15. doi: 10.1186/2046-2530-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Johnson CA, Collis SJ. Ciliogenesis and the DNA damage response: a stressful relationship. Cilia. 2016;5:19. doi: 10.1186/s13630-016-0040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hassounah NB, Bunch TA, McDermott KM. Molecular pathways: the role of primary cilia in cancer progression and therapeutics with a focus on Hedgehog signaling. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2012;18:2429–2435. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Plotnikova OV, Golemis EA, Pugacheva EN. Cell cycle-dependent ciliogenesis and cancer. Cancer research. 2008;68:2058–2061. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Seeger-Nukpezah T, Little JL, Serzhanova V, Golemis EA. Cilia and cilia-associated proteins in cancer. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2013;10:e135–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Shagisultanova E, Gaponova AV, Gabbasov R, Nicolas E, Golemis EA. Preclinical and clinical studies of the NEDD9 scaffold protein in cancer and other diseases. Gene. 2015;567:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.04.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Janecek M, Rossmann M, Sharma P, Emery A, Huggins DJ, Stockwell SR, Stokes JE, Tan YS, Almeida EG, Hardwick B, Narvaez AJ, Hyvonen M, Spring DR, McKenzie GJ, Venkitaraman AR. Allosteric modulation of AURKA kinase activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of its protein-protein interaction with TPX2. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28528. doi: 10.1038/srep28528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Shagisultanova E, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Golemis EA. Issues in interpreting the in vivo activity of Aurora-A. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:187–200. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.981154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]