Abstract

Background

Genetic material from large patient cohorts is increasingly central to translational genetic research. However, patient blood samples are a finite resource and their supply and storage are often dictated by clinical and not research protocols. Our experience supports difficulty in amplifying DNA from blood stored in herparin; a scenario that other researchers may have or will encounter. This technical note describes a number of simple steps that enable successful PCR amplification.

Methods

DNA was extracted using the Illustra Nucleon Genomic DNA Extraction Kit. PCR amplification was attempted using a number of commercially available PCR mastermixes.

Results

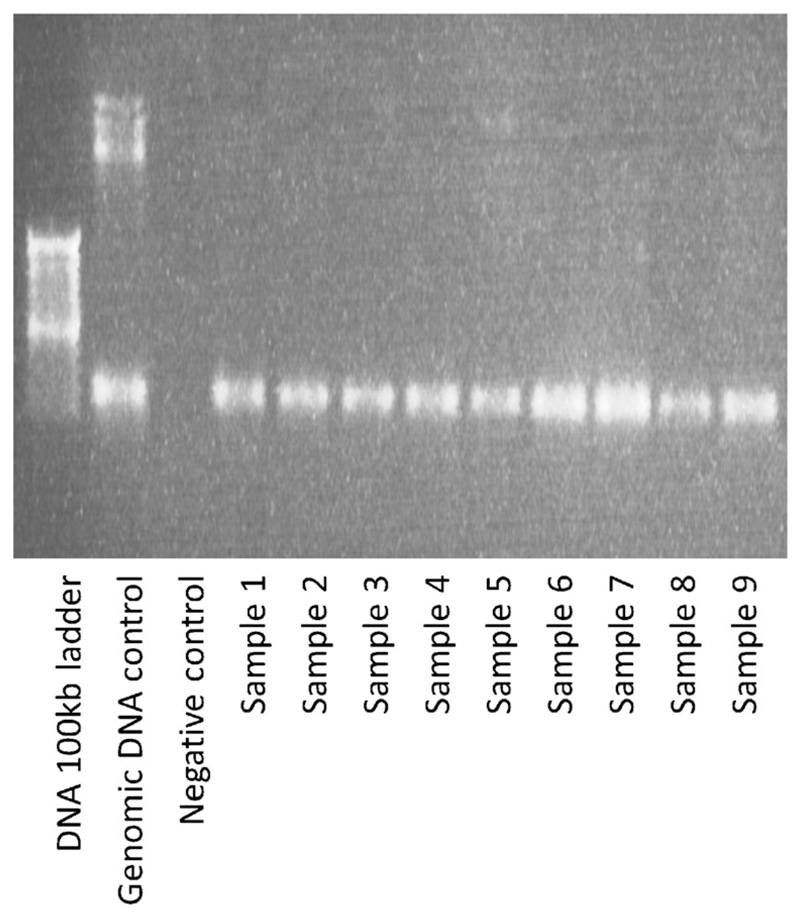

PCR DNA amplification failed using ReddyMix™ PCR Master Mix, Thermo-Start® (Thermo Scientific Inc. US) and ZymoTaq™ (Zymo research, US) PCR mastermixes, as demonstrated absence of products on gel electrophoresis. However, using the Invitrogen™ (Thermo Scientific Inc., US) Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase, PCR products were identified on a 1% agarose gel for all samples. PCR products were cleaned with ExoSAP-IT® (Affymetrix Inc., US) and a sequencing reaction undertaken using a standard Big Dye protocol. Subsequent genotyping was successful for all samples for alleles at the CDH1 locus.

Conclusion

From our experience a standard phenol/chloroform purification and using the Invitrogen™ Platinum® Taq has enabled the amplification of whole blood samples taken into lithium heparin and stored frozen for up to a month. This simple method may enable investigators to utilise blood taken in lithium heparin for DNA extraction and amplification.

Keywords: Single nucleotide polymorphism, Polymerase chain reaction, Heparin

Dear Editor,

Genetic material from large patient cohorts is increasingly central to translational genetic research. However, patient samples are not an infinite or ideal resource: the amount available to the researcher, the receiver used, or storage conditions may not be prescribed by the researcher but by clinical, practical or ethical considerations. Recently our group was required to undertake gene sequencing on a number of blood samples that had been taken into lithium heparin blood bottles and stored frozen for up to 1 month. Initial attempts at DNA extraction and amplification with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were unsuccessful and a literature search revealed historical reports of similar difficulties [1, 2]. It was not immediately possible or practical to repeat the blood samples for these patients using an EDTA or other receiver that does not contain heparin. Therefore, in an attempt to overcome this problem, we performed a clean-up of the DNA samples using a standard phenol/chloroform protocol, followed by PCR using a number of readily available Taq polymerases. PCR was successful with the Platinum®Taq polymerase as demonstrated by gel electrophoresis and subsequent successful DNA sequencing and genotyping for alleles at the CDH1 locus.

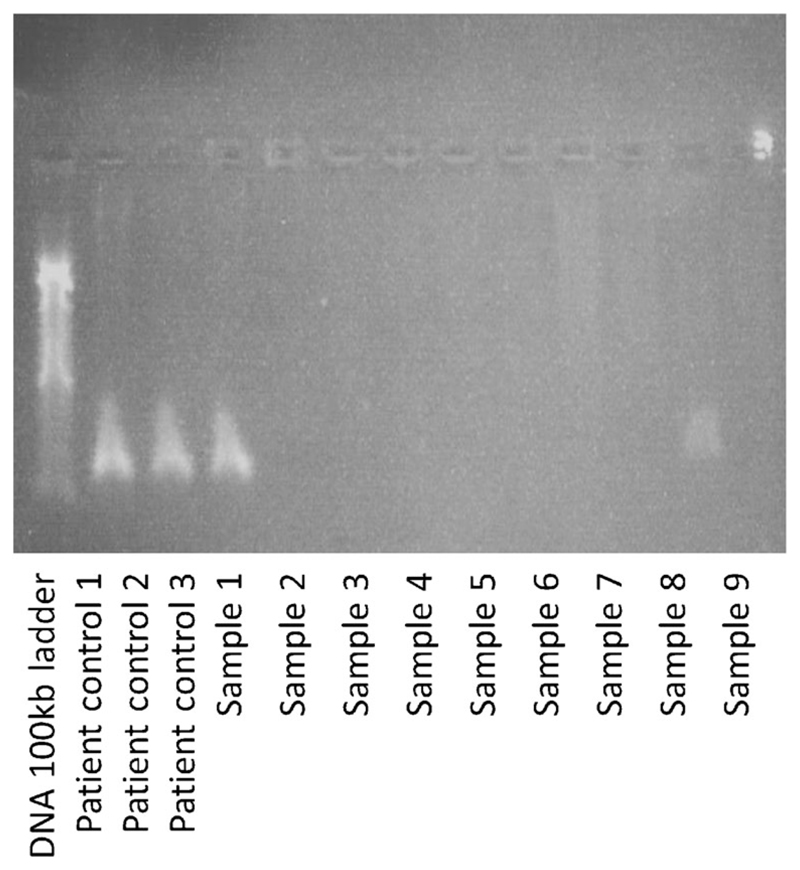

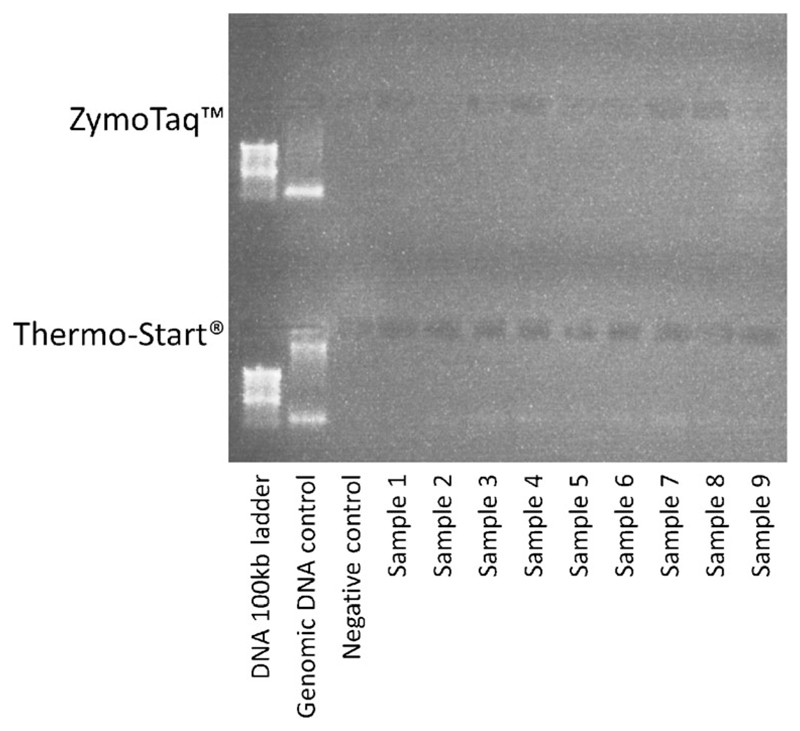

Over a period of 2 weeks, we collected ~9 ml blood from each of 9 subjects into a lithium heparin bottle (S-Monovette® bottle containing heparin coated beads; heparin concentration ~ 16 IU.ml; Sarstedt AG & Co., Germany). Following two inversions of the bottle, 1 ml of whole blood was drawn off and frozen at −80° centigrade. The remaining blood was processed for plasma and RNA extraction. The frozen sample was recovered after 2–4 weeks. After thawing, DNA was extracted using the Illustra Nucleon Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, UK). In brief, this process involves cell lysis using the provided reagent (containing Triton X-100) followed by deproteinisation with Sodium Perchlorate, stratification using chloroform and Nucelon resin, and DNA phase extraction, precipitation and washing. The DNA was re-suspended in TE (Tris and EDTA) buffer on a rotary shaker for 24 h. Attempted PCR amplification of the recovered genomic DNA alongside a positive control using the ReddyMix™ PCR Master Mix was unsuccessful as demonstrated by gel electrophoresis (using a standard 1 % agarose gel) (Fig. 1). In an attempt to facilitate successful DNA amplification, samples were washed using a standard phenol/chloroform protocol. In brief, equal amounts of chloroform and phenol were added to the DNA dissolved in TE to make up twice the initial volume. Following centrifugation, the upper phase was recovered and extracted by DNA precipitation and re-suspended in TE buffer. Following clean-up, PCR amplification was again unsuccessful when using the ReddyMix™, Thermo-Start® (Thermo Scientific Inc. US) and ZymoTaq™ (Zymo research, US) PCR mastermixes, as demonstrated by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). However, using the Invitrogen™ (Thermo Scientific Inc., US) Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase (20 μl per 15 ng genomic DNA, master mix made using 70 μl water, 10 μl 10× PCR buffer, 5 μl MgCl2, 5 μl dNTP at 1.25 μmol, 5 μl reverse primer, 5 μl forward primer, and 0.5 μl Platinum® Taq) PCR products were identified on a 1 % agarose gel for all 9 samples (Fig. 3). PCR products were cleaned with ExoSAP-IT® (Affymetrix Inc., US) and a sequencing reaction undertaken using a standard Big Dye protocol. Subsequent genotyping was successful for all samples for alleles at the CDH1 locus.

Fig. 1.

1 % Agarose gel stained with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, demonstrating absence of PCR products for samples taken in into lithium heparin bottles

Fig. 2.

1 % Agarose gel stained with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, demonstrating absence of PCR products using the ZymoTaq™ and Thermo-Start® PCR mastermixes

Fig. 3.

1 % Agarose gel stained with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide, demonstrating PCR products using the Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase

Here we describe our initial difficulty and subsequent success in extracting and amplifying genomic DNA from blood stored in lithium heparin anticoagulant. Similar difficulties have been previously reported. A previous letter by Satsangi et al. described the difficulty in amplifying DNA from heparinized frozen whole blood (5–20 units heparin/ml) despite strategies to enhance amplification including altering the DNA or magnesium concentration and using alternative DNA polymerases. However, the authors did report that some amplification was possible in samples stored for less than 3 months and those taken into lower doses of heparin. Two more recent studies have reported similar difficulties [2, 3] concluding that heparin likely inhibits both reverse transcriptase and Taq polymerase. A number of studies have investigated steps to overcome the above difficulties, including the use of heparinase [4, 5] yet such steps may be prohibitively costly, time-consuming, or ineffective after prolonged sample freezing [1].

From our experience a standard phenol/chloroform purification and using the Invitrogen™ Platinum® Taq has enabled the amplification of whole blood samples taken into lithium heparin and stored frozen for up to a month. This simple method may enable investigators to utilise blood taken in lithium heparin for DNA extraction and amplification, thus reducing repeat blood sampling for patients or enabling inclusion of patients where further blood sampling is not possible.

Funding sources

PVS: Melville Trust for Care and Cure of Cancer 1 year research fellowship, Tenovus small research grant E13/01, One Year Research Fellowship supported by Harold Bridges Request, MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship MR/M004007/1.

LYO: Cancer Research UK Research Training Fellowship (C10195/A12996).

NG: Medical Research Council Grant MR/J00913X/1.

SMF: Medical Research Council Grant MR/K018647/1.

MGD: Cancer Research Programme Grant C348/A12076.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Satsangi J, Jewell D, Welsh K, Bunce M, Bell J. Effect of heparin on polymerase chain-reaction. Lancet. 1994;343:1509–1510. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willems M, Moshage H, Nevens F, Fevery J, Yap SH. Plasma collected from heparinized blood is not suitable for Hcv-Rna detection by conventional Rt-Pcr assay. J Virol Methods. 1993;42:127–130. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90184-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Soud WA, Radstrom P. Purification and characterization of PCR-inhibitory components in blood cells. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:485–493. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.485-493.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor AC. Titration of heparinase for removal of the PCR-inhibitory effect of heparin in DNA samples. Mol Ecol. 1997;6:383–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1997.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Izraeli S, Pfleiderer C, Lion T. Detection of gene expression by PCR amplification of RNA derived from frozen heparinized whole blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6051. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.21.6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]