Abstract

Introduction

A few studies have examined the costs of breast cancer treatment in a Medicaid population at the state level. However, no study has estimated medical costs for breast cancer treatment at the national level for women aged 19–44 years enrolled in Medicaid.

Methods

A sample of 5,542 younger women aged 19–44 years enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid with diagnosis codes for breast cancer in 2007 were compared with 4.3 million women aged 19–44 years enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid without breast cancer. Nonlinear regression methods estimated prevalent treatment costs for younger women with breast cancer compared with those without breast cancer. Individual medical costs were estimated by race/ethnicity and by type of services. Analyses were conducted in 2013 and all medical treatment costs were adjusted to 2012 U.S. dollars.

Results

The estimated monthly direct medical costs for breast cancer treatment among younger women enrolled in Medicaid was $5,711 (95% CI=$5,039, $6,383) per woman. The estimated monthly cost for outpatient services was $4,058 (95% CI=$3,575, $4,541), for inpatient services was $1,003 (95% CI=$708, $1,298), and for prescription drugs was $539 (95% CI=$431, $647). By race/ethnicity, non-Hispanic white women had the highest monthly total medical costs, followed by Hispanic women and non-Hispanic women of other race.

Conclusions

Cost estimates demonstrate the substantial medical costs associated with breast cancer treatment for younger Medicaid beneficiaries. As the Medicaid program continues to evolve, the treatment cost estimates could serve as important inputs in decision making regarding planning for treatment of invasive breast cancer in this population.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor among U.S. women, accounting for about 30% of incident cancers.1 It is one of the most costly medical conditions to treat.2 Women aged 18–44 years account for 11% of new cases.3 These women tend to experience more-aggressive types of breast cancer, requiring intensive and expensive treatment with lower survival rates compared with older women.4,5 The health and economic outcomes may be worse among younger women with lower SES, such as those enrolled in Medicaid. This may be due in part to Medicaid beneficiaries being more likely to present with advanced-stage cancers than patients with private insurance.4,6–10

Access to breast cancer treatment is crucial for long-term survival. However, treatment costs can impose substantial financial burden, particularly for younger women and those of lower SES.11–15 Further, access to treatment and financial burden issues may be a greater challenge for Medicaid patients.13–15 For instance, in one colon cancer study, the authors found that 21% of Medicaid patients reported denial of treatment by healthcare providers.13

Few studies have examined breast cancer treatment costs in a Medicaid population.9,13,14,16 These studies have been conducted in select states or small geographically defined settings, which may not generalize to other states, given the large variation in state Medicaid programs.9,13,14,16–18 No study has estimated costs for breast cancer treatment in a nationally representative Medicaid population for younger women. The purpose of this study is to present national-level prevalence cost estimates, representing monthly treatment costs on breast cancer for women aged 19–44 years enrolled in Medicaid in 2007. Further, this study reports total monthly individual medical costs by race/ethnicity, stratified into four mutually exclusive categories: non-Hispanic white (NHW), non-Hispanic black (NHB), non-Hispanic other (NHO), and Hispanic, and by type of service (TOS, i.e., outpatient, inpatient, and prescription drugs).

Methods

Data and Study Population

The current study used Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) claims and enrollment data in 2007,19 which was the most recent year data were available at the start of this study. MAX data are maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and contain data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.19 The study sample included women aged 19–44 years enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid, which includes those in primary care case management and whose only managed care coverage was for dental. The study excluded populations with other insurance groups, such as dual Medicare–Medicaid enrollees and enrollees in capitated managed care plans, because their complete service use may not be reported in the database.20 In the Medicaid program, beneficiaries are not required to have a full year of enrollment, therefore, some are enrolled for relatively short periods of time during a calendar year.21

Payments by Service Type

Because much of the MAX population was enrolled in Medicaid for less than a full calendar year, total Medicaid payments and payments by service types were analyzed by month to accurately reflect the healthcare needs of each individual. Three separate TOSs—inpatient, outpatient, and prescription drugs—were calculated using Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services– generated TOS codes. Because the MAX data set did not provide predefined TOS payment, payments were derived from the MAX file types. The outpatient Medicaid files include services provided by physicians, other practitioners, outpatient hospitals, clinics, and nurse practitioners. The inpatient file contains complete stay records for enrollees who used inpatient services, including diagnoses, procedures, discharge status, length of stay, and payment amount. Prescription drug files in Medicaid include payments for drugs as well as durable medical equipment. Analysis of point of service was restricted to fee-for-service beneficiaries only. All medical treatment costs were adjusted to 2012 U.S. dollars using the Personal Health Care Expenditure Price Index.22

Breast Cancer Identification

Three ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes were used to classify beneficiaries with breast cancer: a malignant neoplasm of the female breast (174), carcinoma in situ of breast (233.0), or a history of malignant breast neoplasms (V10.3).23 Beneficiaries with any inpatient or long-term care claims with any of these ICD-9-CM codes were identified as breast cancer patients. To exclude breast cancer screenings or other tests to rule out breast cancer, beneficiaries were also identified as having breast cancer if there were at least two outpatient claims with these ICD-9-CM codes on different days. Female enrollees aged 19–44 years not identified as having breast cancer were used as the comparison population in the study.

Matching Procedure

Propensity score was used to match younger women with breast cancer from the database to younger women without breast cancer. The propensity score estimates the probability of being in the breast cancer group based on patient characteristics using predicted probabilities via a probit regression. The predicted values from the probit regression summarize multiple patient characteristics into a single propensity score, with similar scores indicating overlap in patient characteristics.24 The probit model included the proportion of the year enrolled in Medicaid, age, race/ethnicity, state, a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) exclusive of cancer, an indicator for cancer diagnosis, and 12 comorbid conditions. Nearest neighbor matching was used to pair a breast cancer patient with a non–breast cancer comparison woman. Because covariate balance may not hold for subsets of the matched sample, the authors rematched using nearest neighbor matching for each of the race/ethnicity subgroups.25

Demographic variables in the MAX data included proportion of the year enrolled in Medicaid, age, race/ethnicity, state of residence, and Medicaid plan type. The proportion of the year enrolled was calculated as the number of months enrolled divided by 12. The age variable was coded into 5-year age categories: 19–23, 24–28, 29–33, 34–38, and 39–44 years. The race/ethnicity variable was stratified into four mutually exclusive categories: NHW, NHB, NHO, and Hispanic. State identifiers were included in matching to adjust for state-level effects, relating to the differences in state Medicaid benefits.

The CCI excluded diagnosis codes for cancers: any malignancy, leukemia and lymphoma, and metastatic solid tumors.26 To adjust for cancers not included in the CCI, two samples were matched on a single cancer variable, which included ovarian, colorectal, lung, cervical, skin, and leukemia and lymphoma. Because the CCI includes comorbidities that are most relevant to an older population, 12 conditions with prevalence of at least 0.5% (e.g., pregnancy, injuries, and hypertension) were included as covariates in the multivariable regression models.

Statistical Analysis

Data on medical costs are usually skewed and using linear regressions may produce biased estimates.27 In this study, a fraction of the study sample had zero medical costs (8%) and some have extremely high medical costs. For instance, 0.85% of beneficiaries have treatment costs more than ten times the sample mean. To reduce the influence of extreme cases and potential bias in the estimates, the authors followed the procedures in Manning and Mullahy27 and Buntin and Zaslavsky28 and performed the Modified Park Test. The two-part generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and a log link was used.27,28 The first part of the two-part model was a logistic regression to predict the probability of any medical expenditure. The second part was a generalized linear model comprised of individuals with positive medical expenditures. The Modified Park Test was performed after running the regressions. The results indicated that the gamma family of distributions was the best fit in most cases (and second best in all others). Therefore, a gamma family distribution was used for all specifications for consistency and the log link passed all specification tests.

Costs attributable to breast cancer were calculated by comparing predicted costs for younger women with breast cancer to predicted costs for those without breast cancer, while holding all other variables constant at mean values. The delta method was used to compute SEs for the estimates. All analyses were conducted in 2013 in Stata, version 13.1.

Results

The sample included 5,542 women aged 19–44 years who were Medicaid enrollees with breast cancer and > 4.3 million Medicaid enrollees without breast cancer. Table 1 presents summary statistics for the breast cancer, comparison, and matched comparison samples. The breast cancer group was older than the comparison sample; almost 64% of the breast cancer sample was aged 39–44 years, compared with 13% of the comparison sample. The breast cancer group also had a slightly higher proportion of Hispanic women. For the breast cancer sample, the unadjusted differences in the total monthly medical costs were four times higher than the comparison group ($3,492 vs $850, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics of Women Enrolled in Medicaid Aged 19–44 Years, by Breast Cancer History, 2007

| Variable | Breast cancer sample (n=5,542) | Comparison sample (n=4,315,514) | Matched comparison sample (n=5,542) | p-value for differences (breast cancer vs matched comparison) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly costs by service type in 2012 U.S. $, M (SD) | ||||

| Total costs | 3,492 (6,101) | 850 (2,291) | 1,184 (2,795) | < 0.01 |

| Outpatient costs | 1,389 (2,661) | 137 (370) | 169 (519) | < 0.01 |

| Inpatient costs | 721 (3,815) | 195 (1,141) | 306 (1,670) | < 0.01 |

| Prescription drug costs | 522 (1,276) | 108 (399) | 231 (555) | < 0.01 |

| Medicaid enrollment | ||||

| Proportion of the year enrolled | 0.831 (0.260) | 0.726 (0.308) | 0.839 (0.256) | 0.06 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 45.63 | 46.30 | 47.10 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 24.69 | 27.20 | 23.45 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 19.01 | 16.82 | 19.01 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 10.67 | 9.68 | 10.44 | 0.48 |

| Age | ||||

| 19–23 years | 0.82 | 31.44 | 0.83 | |

| 24–28 years | 3.43 | 25.10 | 3.28 | |

| 29–33 years | 8.90 | 17.16 | 8.75 | |

| 34–38 years | 22.58 | 13.47 | 22.78 | |

| 39–44 years | 64.26 | 12.83 | 64.35 | 0.99 |

| Charlson Index score | ||||

| 0 | 82.78 | 92.74 | 81.30 | |

| 1 | 12.44 | 5.59 | 13.13 | |

| >1 | 4.78 | 1.67 | 5.58 | 0.15 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cancer diagnosis | 3.86 | 0.35 | 3.74 | 0.77 |

| Hypertension | 11.36 | 3.61 | 12.01 | 0.36 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4.65 | 1.32 | 5.11 | 0.34 |

| Pneumonia | 3.54 | 0.70 | 3.56 | 0.97 |

| Asthma | 5.27 | 2.87 | 5.83 | 0.27 |

| Depression | 9.74 | 5.78 | 9.86 | 0.86 |

| Back problems | 10.91 | 5.10 | 11.70 | 0.26 |

| Skin disorders | 8.80 | 3.01 | 8.91 | 0.87 |

| Injuries | 16.83 | 5.40 | 17.22 | 0.64 |

| Pregnancy | 3.82 | 30.63 | 3.86 | 0.94 |

| Arthritis | 8.11 | 2.82 | 8.86 | 0.23 |

| Mental health/substance abuse | 17.00 | 10.49 | 17.68 | 0.42 |

| Mental retardation | 1.14 | 1.77 | 1.00 | 0.56 |

Note: State dummies were included in the match. Boldface indicates statistical significance. The p=0.01 level indicates statistically significant differences between the breast cancer sample and the matched comparison sample was 0.987. The Charlson Index is exclusive of cancers. The values for this index range from 0 to 15. Cancer diagnosis includes one of the following cancers: ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, cervical cancer, skin cancer, leukemia and lymphoma.

Data presented in Table 1 indicate that the matching procedure was successful; all covariates were balanced at the 95% level. State indicators (results available upon request) also balanced at the 95% level. Even after matching, the differences in medical expenditures between the breast cancer and matched comparison samples were large ($3,492 vs $1,184; p < 0.01). The results of matching for subsamples by race/ethnicity are presented in Appendix Tables 1–4 (available online).

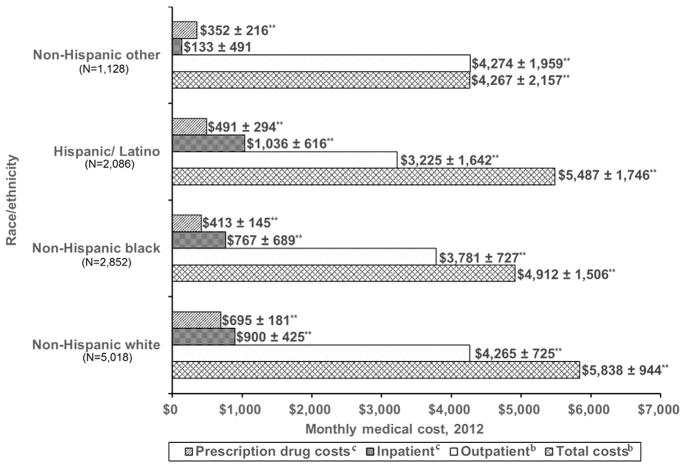

Figure 1 presents the estimated monthly attributable breast cancer medical costs by point of service and race/ethnicity. The estimated total monthly medical cost was $5,838 (95% CI=4,894, $6,782) for NHWs, $5,487 (95% CI=$3,741, $7,233) for Hispanics, and $4,912 (95% CI=$3,406, $6,418) for NHBs. In general, the estimated total monthly treatment costs by race/ethnicity were statistically significant at p < 0.01. By point of service, the estimated medical costs for outpatient services for NHOs was $4,274 (95% CI=$2,315, $6,233), which was significantly higher than NHWs ($4,265, 95% CI=$3,540, $4,990). For inpatient services, Hispanics had the highest estimated monthly medical cost ($1,036, 95% CI=$420, $1,652), followed by NHWs ($900, 95% CI=$475, $1,325). For prescription drug costs, NHWs had highest estimated medical cost of $695 (95% CI=$514, $876) and NHOs had significantly lowest cost of $352 (95% CI=$136, $568).

Figure 1.

Estimated monthly medical costs per woman with breast cancer among Medicaid enrollees aged 19–44 years, by race/ethnicity and by type of service.

aThe reported monthly treatment cost estimates by point of service may not add up to the total cost. This is because the MAX dataset does not provide predefined point of service costs.

bEstimate obtained through use of a one part model: GLM with gamma distribution.

cEstimate obtained through use of two-part model: logit as first stage, GLM with gamma distribution and log link as second stage.

**p < 0.01 and 95% CI=mean±margin of error.

GLM, generalized linear model; MAX, Medicaid Analytic eXtract.

Estimates for the two-part regression models by point of service are presented in Table 2. The total monthly medical cost attributable to breast cancer was estimated to be $5,711 (95% CI=$5,039, $6,383). The estimated cost for each point of service was $4,058 (95% CI=$3,575, $4,541) for outpatient, $1,003 (95% CI=$708, $1,298) for inpatient, and $539 (95% CI=$431, $647) for prescription drug costs. These estimated monthly medical costs were significant at p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Estimated Monthly Breast-Cancer Attributable Medical Care Costs per Woman With Breast Cancer Among Medicaid Enrollees Aged 19–44 years, by Point of Service

| Point of servicea | Overall (n = 11,084) | 95% CI, U.S.$ |

|---|---|---|

| Total costsb | $5,711 | 5,039, 6,383 |

| Outpatientb | $4,058 | 3,575, 4,541 |

| Inpatientc | $1,003 | 708, 1,298 |

| Prescription drug costsc | $539 | 430, 647 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p < 0.01).

The reported monthly treatment cost estimates by point of service may not add up to the total cost. This is because MAX dataset does not provide predefined point of service costs. In the study, we used the MAX Type of service codes to categorize the outpatient, inpatient, and prescription drug costs. However, the variable for the total payment cost was predefined in MAX database, which includes many type of service codes that cannot be easily categorized as a component in each of the three points of service defined for this study. This means that the reported cost estimates by point of service will be less than the total cost. For example, the sum of the estimated cost by point of service presented in this Table was $5,600, which is 1.94% less than the total of $5,711.

Estimate obtained through use of a one part model: generalized linear model with gamma distribution.

Estimate obtained through use of two-part model: logit as first stage, generalized linear model with gamma distribution and log link as second stage. Further, the inpatient and prescription drug costs regressions have zeroes in >10% of the sample, which necessitated the use of a two-part model.

MAX, Medicaid Analytic eXtract.

Discussion

This study provides national prevalence estimates of monthly medical costs for breast cancer treatment among women aged 19–44 years enrolled in Medicaid. The estimated monthly direct medical costs ranged from $5,039 to $6,383 per woman. By point of service, the estimates ranged from $3,575 to $4,541 for outpatient services, $708 to $1,298 for inpatient services, and $430 to $647 for prescription drug costs. NHW women had the highest monthly total medical costs, whereas NHO women had the lowest. The cost estimates reported in this study demonstrate the substantial medical costs associated with breast cancer treatment among younger Medicaid beneficiaries. These findings under-score the fact that Medicaid beneficiaries have a higher probability of being diagnosed with advanced-stage cancers, including breast cancer, than privately insured women.7,29,30

Patterns of monthly medical costs by point of service differed by race/ethnicity. NHO and NHW women had significantly higher medical costs for outpatient services than monthly costs of treating other racial/ethnic groups. For inpatient service, Hispanic and NHW women had significantly higher medical costs than costs of treating other racial/ethnic groups. On the other hand, the monthly medical costs of prescription drugs were significantly higher for NHW and Hispanic women than that of other racial/ethnic groups. Therefore, interpreting the variability in monthly treatment costs as disparities may not be straightforward. This is because breast cancer treatment costs vary by stage of diagnosis and subsequent prognosis, types of chemotherapeutic choices recommended to the patient and associated costs, and other anticancer treatment that the patient may undertake on a month-to-month basis. Further, the study data lack clinical information to ascertain the severity of breast cancer in the study population. Therefore, the authors are faced with the same difficulties that previous studies have encountered: the inability to identify whether disparities in cancer treatment costs among Medicaid population are driven by differences in access to indicated treatment, coordination of care, or patient characteristics, including health status and socioeconomic differences.18,31,32

As stated earlier, the few prior studies that have examined the costs of breast cancer treatment in a Medicaid population have been conducted in state-specific or small geographically defined settings.9,13,14,16 As a result, the findings in these studies are not generalizable and may not be consistent with the national estimates reported in this paper. For example, Subramanian et al.9 conducted a study on treatment cost for breast cancer patients enrolled in Medicaid in North Carolina and estimated that the incremental costs at 24 months after diagnosis were $22,343, $41,005, and $117,033 for those with local, regional, and distant breast cancers, respectively. Khanna and colleagues16 found that, for a woman with breast cancer in the 2005 West Virginia Medicaid population, fee-for-service all-cause healthcare costs were $3,321 higher (p < 0.0001).

According to the recent report to the nation on the status of cancer, rates for cancer incidence and mortality, including breast cancer, have continued to decline.33 Though this progress is important, the treatment costs are expected to continue rising into the future34 due to the increasing number of new cancer cases, costs of new cancer therapies, increasing use of chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and other anticancer drugs.35–37 Several studies have found that the rising cost of cancer care is a major barrier to healthcare access among cancer patients, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities, individuals with low SES, or those who are uninsured or underinsured.12,38–42 The ongoing increase in the cost of cancer treatment has not gone unnoticed.43–45 A recent report by IOM, “Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care,” included the cost of care as a component of quality of cancer care.44 Further, other medical organizations have identified affordability as a critical issue adversely affecting clinical outcomes, increased risk of recurrence, and poorer disease-free survival.46–48 In 2013, the American Society of Clinical Oncology published “Action Brief: Value in Cancer Care,” which emphasized the role of oncologists in communicating with patients about the costs of cancer care.46

The implementation of Affordable Care Act is expected to provide many opportunities to increase health insurance coverage. For example, millions of Americans are newly eligible for Medicaid, given expansions in many states. Increasing insurance coverage can help reduce financial barriers to treatment and provide individuals with better access to health services. With increased Medicaid enrollment, Medicaid expenditures for cancer treatment will likely increase, including breast cancer treatment costs. In addition to implementation of the Affordable Care Act, it is important that public health agencies, insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and patient groups work together to identify solutions to reduce the rising cost of cancer care and to promote high-value, high-quality cancer care for millions of Americans, including low-income women newly enrolled in Medicaid.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the reported medical costs did not take into account the opportunity costs associated with patient time spent receiving medical care, such as traveling to and from care, waiting for appointments, or consulting with physicians and other providers. Similarly, the reported costs did not account for other nonmedical expenses, such as child care, lodging/respite care, food, and productivity losses for caregivers. Second, data used in this study lack information on the stage to measure the severity of breast cancer at diagnosis in the study population. Thus, the authors could not separate monthly treatment cost estimates by stage at diagnosis. For example, in the study, the authors could not ascertain whether women with ductal carcinoma in situ were included in the claims data or the magnitude of payment to their breast cancer treatment. As a result, they reported aggregate (prevalence based) monthly treatment cost estimates, which have several useful benefits.49 However, previous studies have reported that treatment costs increase by stage at diagnosis.9,50 Third, because of possible coding errors that may occur during claims process, the algorithm used may not have fully identified breast cancer patients. Thus, the reported results may underestimate the true costs of breast cancer treatment in this population. Fourth, data used in this study are from 2007 and the results reflect the monthly cost of breast cancer treatment in that year. Fifth, the analysis was focused on fee-for-service Medicaid; Medicaid managed care was excluded and, in recent years, the proportion of Medicaid recipients enrolled in Managed Care has been increasing. Sixth, because of potential barriers for Medicaid beneficiaries to receive adequate medical care, there is a tendency of undertreatment in this population. Therefore, the estimated treatment costs may be under-reported. Finally, the reported monthly treatment cost by point of service may not add up to the total cost. This is because MAX data do not provide predefined point of service costs. This study used MAX TOS codes to categorize outpatient, inpatient, and prescription drug costs. However, the variable for the total payment cost was predefined in the MAX database, which includes many TOS codes that cannot be easily categorized as a component in each of the three points of service defined for this study. This means that the reported cost estimates by point of service may be less than the total cost. For example, the sum of the estimated cost by point of service presented in Table 2 was $5,600, which is 1.94% less than the total cost of $5,711.

Conclusions

These findings add to the growing concern about the costs of cancer care and its negative impact on clinical care to Medicaid populations and their families. The effects of these high treatment costs are more severe for younger cancer patients, who have two to five times higher rates of filing bankruptcy than older cancer patients.51 Therefore, there is a need for greater awareness beyond the oncology community about the costs imposed by breast cancer in younger women, especially those in Medicaid. As the Medicaid program continues to evolve, the treatment cost estimates reported herein could provide important input for decision making and planning for treatment of invasive breast cancer in the Medicaid population. Further, these estimates could be invaluable inputs in modeling interventions to estimate the cost effectiveness of invasive breast cancer treatment in women enrolled in Medicaid.

Supplementary Material

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.10.017.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Jardines L, Goyal S, Fisher P, Weitzel J, Royce M, Goldfarb SB. [Accessed May 15, 2015];Breast cancer overview: risk factors, screening, genetic testing, and prevention. www.cancernetwork.com/cancer-management/breast-cancer-overview-risk-factors-screening-genetic-testing-and-preventionsthash.8FEFkj8a.dpuf.

- 2.Soni A. [Accessed January 22, 2015];The five most costly conditions, 1996 and 2006: estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. 2009 http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st248/stat248.pdf.

- 3.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2010 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. DHHS, CDC, National Cancer Institute; 2013. [Accessed May 15, 2015]. www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A. Breast cancer before age 40 years. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):237–249. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredholm H, Eaker S, Frisell J, Holmberg L, Fredriksson I, Lindman H. Breast cancer in young women: poor survival despite intensive treatment. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007695. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker LC, Royalty AB. Medicaid policy, physician behavior, and health care for the low-income population. J Human Resources. 2000;35(3):480–502. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/146389. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halpern MT, Ward EM, Pavluck AL, Schrag NM, Bian J, Chen AY. Association of insurance status and ethnicity with cancer stage at diagnosis for 12 cancer sites: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):222–231. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Malley CD, Shema SJ, Clarke LS, Clarke CA, Perkins CI. Medicaid status and stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2179–2185. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072553. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.072553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramanian S, Trogdon JG, Ekwueme DU, Gardner J, Whitmire J, Rao C. Cost of breast cancer treatment in Medicaid: Implications for state programs providing coverage for low-income women. Med Care. 2011;49(1):89–95. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IOM. Coverage Matters: Insurance and Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, Taylor DH, Goetzinger AM, Zhong X. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119(20):3710–3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jagsi R, Pottow JAE, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(12):1269–1276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocekt health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(20):2821–2826. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna R, Madhavan SS, Bhanegaonkar A, Remick SC. Prevalence, healthcare utilization, and costs of breast cancer in a state Medicaid fee-for-service program. J Womens Health. 2011;20(5):739–747. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2298. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabik LM, Tarazi WW, Bradley CJ. State Medicaid expansion decisions and disparities in women’s cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):490–496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [Accessed March 2015];Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) General Information. 2012 www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MAXGeneralInformation.html.

- 20.Byrd V, Verdier J, Nysenbaum J, Schoettle A. Technical Assistance for Medicaid Managed Care Encounter Reporting to the Medicaid Statistical Information System, 2010. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Short PF, Graefe DR, Churn SC. How Instability of Health Insurance Shapes America’s Uninsured Problem. New York, NY: The Common-wealth Fund; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed October, 18 2014];Using the appropriate price indices for analyses of health care expenditures or income across multiple years. http://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml.

- 23.Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Bajorunaite R, Sparapani RA, Freeman JL. An algorithm for the use of Medicare claims data to identify women with incident breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1733–1749. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00315.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. IZA Discussion Papers. 2005;(1588) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehejia R. Practical propensity score matching: a reply to Smith and Todd. J Econom. 2005;125(1–2) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.04.012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning W, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20(4):461–494. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buntin M, Zaslavsky A. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Disparities in cancer diagnosis and survival. Cancer. 2001;91:178–188. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<178::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-s. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<178::AID-CNCR23>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roetzheim RG, Gonzalez EC, Ferrante JM, Pal N, Van Durme DJ, Krischer JP. Effects of health insurance and race on breast carcinoma treatments and outcomes. Cancer. 2000;89(11):2202–2213. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2202::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-l. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2202::AID-CNCR8>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sabik LM, Bradley CJ. Differences in mortality for surgical cancer patients by insurance and hospital safety net status. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(1):84–97. doi: 10.1177/1077558712458158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077558712458158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradley CJ, Gardiner J, Given CW, Roberts C. Cancer, Medicaid enrollment, and survival disparities. Cancer. 2005;103(8):1712–1718. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20954. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohler AB, Sherman RL, Howlader N, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty, and state. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):1–26. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weir HK, Thompson TD, Soman A, Møller B, Leadbetter S. The past, present, and future of cancer incidence in the United States: 1975 through 2020. Cancer. 2015;121(11):1827–1837. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard DH, Bach PB, Berndt ER, Conti RM. Pricing in the market for anticancer drugs. J Econ Perspectives. 2015;29(1):139–162. doi: 10.1257/jep.29.1.139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conti RM, Fein AJ, Bhatta SS. National trends in spending on and use of oral oncologics, first quarter 2006 through third quarter 2011. Health Aff. 2014;33:1721–1727. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirchhoff AC, Lyles CR, Fluchel M, Wright J, Leisenring W. Limitations in health care access and utilization among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5964–5972. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Alley LG, Pollack LA. Health insurance coverage and cost barriers to needed medical care among U.S. adult cancer survivors age<65 years. Cancer. 2006;106(11):2466–2475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21879. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM. Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3493–3504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keegan TH, Tao L, DeRouen MC, et al. Medical care in adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: what are the biggest access-related barriers? J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(2):282–292. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0332-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0332-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King CJ, Chen J, Dagher RK, Holt CL, Thomas SB. Decomposing differences in medical care access among cancer survivors by race and ethnicity. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(5):459–469. doi: 10.1177/1062860614537676. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1062860614537676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nass SJ, Patlak M. Ensuring Patient Access to Affordable Cancer Drugs: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.IOM. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting A New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Society of Clinical Oncology. [Accessed January 22, 2015];ASCO in action brief: value in cancer care. 2015 www.asco.org/advocacy/asco-action-brief-value-cancer-care.

- 47.Smith EC, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Delay in surgical treatment and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in young women by race/ethnicity. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):516–523. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1680. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barron TI, Cahir C, Sharp L, Bennett K. A nested case-control study of adjuvant hormonal therapy persistence and compliance, and early breast cancer recurrence in women with stage I–III breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1513–1521. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yabroff KR, Warren JL, Banthin J, et al. Comparison of approaches for estimating prevalence costs of care for cancer patients: what is the impact of data source? Med Care. 2009;47(7 suppl 1):S64–S69. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a23e25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a23e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell JD, Ramsey SD. The costs of treating breast cancer in the U.S.: a synthesis of published evidence. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(3):199–209. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200927030-00003. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200927030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(6):1143–1152. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.