Abstract

Objectives

Healthcare workers have high rates of low back pain (LBP) related to handling patients. A large chain of nursing homes experienced reduced biomechanical load, compensation claims and costs following implementation of a safe resident handling programme (SRHP). The aim of this study was to examine whether LBP similarly declined and whether it was associated with relevant self-reported occupational exposures or personal health factors.

Methods

Worker surveys were conducted on multiple occasions beginning with the week of first SRHP introduction (baseline). In each survey, the outcome was LBP during the prior 3 months with at least mild severity during the past week. Robust Poisson multivariable regression models were constructed to examine correlates of LBP cross-sectionally at 2 years (F3) and longitudinally at 5–6 years (F5) post-SRHP implementation among workers also in at least one prior survey.

Results

LBP prevalence declined minimally between baseline and F3. The prevalence was 37% at F3 and cumulative incidence to F5 was 22%. LBP prevalence at F3 was positively associated with combined physical exposures, psychological job demands and prior back injury, while frequent lift device usage and ‘intense’ aerobic exercise frequency were protective. At F5, the multivariable model included frequent lift usage at F3 (relative risk (RR) 0.39 (0.18 to 0.84)) and F5 work–family imbalance (RR=1.82 (1.12 to 2.98)).

Conclusions

In this observational study, resident lifting device usage predicted reduced LBP in nursing home workers. Other physical and psychosocial demands of nursing home work also contributed, while frequent intense aerobic exercise appeared to reduce LBP risk.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare workers have high rates of low back pain (LBP) related to handling patients.1–5 There is mixed but primarily positive evidence that interventions to provide mechanical lifts to nursing workforces reduce LBP occurrence.1,4,6–11

Among the longitudinal studies that have examined LBP after introduction of mechanical lifts, most have considered compensation claim rates as the outcome. A 1-year follow-up period following intervention was reported in several studies12–14 and longer periods by other investigators.7,10,15–18 Almost all of these observed a reduction in back injury claim rates and/or costs in association with lift usage, but one had mixed results.10

Fewer studies have examined LBP symptoms as an intervention outcome. Two reported symptom reduction within 1 year,4,19 and another showed improvement in musculoskeletal comfort within 6 months postintervention.17 A fourth found no benefit but was judged in one review to be flawed methodologically.6

Thus, there is a dearth of evidence regarding within-individual change in back pain status among healthcare workers provided with lifting device programmes, and few studies with extended follow-up after programme implementation. Further, we can find no published reports of whether personal health factors (eg, obesity) might modify programme effect on back pain at an individual level.

We have recently evaluated a multifaceted safe resident handling programme (SRHP) implemented by a large chain of skilled nursing facilities in the USA. The primary components of this programme were the provision of sufficient mechanical lifts for the specific residents in each centre, protocols for equipment and sling maintenance, and training.20 A detailed description of the programme was previously published.20 Pre–post-intervention observational analyses showed reductions in observed ergonomic exposures and biomechanical load, and in workers’ compensation claim rates and costs within 3 years following the SRHP.20–22

Repeated workforce surveys in selected facilities of this company provided an opportunity to examine LBP prevalence and risk for up to 6 years after the SRHP was introduced. This longitudinal cohort enabled investigation of the following aims:

To examine whether there was a reduction in LBP prevalence and risk following SRHP implementation, concurrent with the effect on workers’ compensation claim rates.

To examine whether LBP prevalence and risk following SRHP implementation were associated with self-reported lift device usage, other occupational exposures and/or health behaviours.

METHODS

Study cohort and survey instrument

This study was part of the ‘ProCare’ study of nursing home employee health which began in 2006 and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Lowell (approvals 06-1403 and 12-056). The study population consisted of workers from multiple facilities within a single company; only those employed directly by the company were included, as previously described.23 By design, the vast majority of study respondents (eg, 87% at 2 years post-SRHP introduction) consisted of clinical staff, specifically nurses and nursing aides.

Questionnaires were self-administered at all survey periods (see next paragraph). Items included demographic characteristics (age, race, gender, marital status, years of education, height, weight), physical and psychosocial work exposures, recent medical history (prior back injury, chronic disease), work–family imbalance, holding a second job, years of seniority, job title, and health behaviours such as smoking status (current/former/never) and frequency of intense aerobic exercise.

The baseline survey was conducted in the week that the SRHP was implemented. For this report, we used data from surveys conducted at baseline (F0) and at 1 year (F2), 2 years (F3) and 5–6 years (F5) after baseline. Owing to design requirements of the continued study, four of the centres surveyed at F3 were not surveyed at F5.

Outcome and exposure assessment and variable construction

The study outcome, LBP, was defined as pain in the low back region during the past 3 months (as indicated on a pain diagram), with at least mild severity during the prior week.

Frequency of intense aerobic exercise was assessed through the question, ‘How many times a week on average do you exercise to work up a sweat (at least 20 min per session, eg, fast walking, jogging, bicycling, swimming, rowing, etc)?’. ‘Chronic disease’ was defined as a diagnosis or treatment for any of: diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol. Body mass index (BMI) categories were defined in the standard way.24

A composite score for occupational physical exposure (range 5–20) was constructed as the mean of five self-reported items (heavy lifting, rapid continuous physical activity, whole body awkward posture, head and arm awkward posture, and kneeling/squatting) assessed on a four-point Likert scale. Decision latitude (range 2–8), psychological job demands (range 2–8) and social support (sum of coworker support and supervisor support; range 4–16) were assessed through a short version of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ).25 Frequency of lift usage was assessed through the question, ‘In general, when you move patients, how often do you use a patient lifting device?’. Possible responses included ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ and ‘always’. Lift usage frequency was dichotomised into always/often/sometimes=1, and never/rarely=0 in modelling (see below). Work–family imbalance, perceived safety at work (safety climate) and physical assault were defined as previously described.26 Schedule control (range 2–8) was defined as the sum of two Likert-scale items extracted from:27 ‘I have a lot to say about how many hours I work per week, including overtime’, and ‘I have a lot to say about which shifts I work (day, afternoon, or evening)’.

Data analysis

The surveys were linked at the individual level (SAS MERGE command). Prevalent LBP was assessed at 2-year follow-up (F3) and incident LBP was assessed at 6-year follow-up (F5). The prospective analysis of incident LBP in F5 was restricted to those workers who had been surveyed on at least one prior occasion (F0, F2 or F3).

Those with current treatment for low back disease or spinal problem or any prior back surgery were designated as ineligible and eliminated from the analysis. Inclusion for cumulative incidence of LBP at F5 was additionally restricted to those with no LBP in any prior survey (ie, F0, F2 and/or F3). Cumulative incidence in other time periods was similarly defined.

Single predictor and multivariable robust Poisson regression models were constructed to determine the association of LBP with occupational and other factors in the same and prior surveys. Since the majority of our multivariable log-binomial models did not converge, robust Poisson regression modelling was used.28 For uniformity of analysis technique and comparability, we used robust Poisson regression for the univariate models as well.

The modelling approach focused on estimating associations with LBP and on identifying potential confounders. The model building was based on first testing the prior hypothesis that lifting device frequency would be associated with LBP. Demographic characteristics from the current survey, as well as exposures and health behaviours from both the current and prior surveys, were then entered into the model.

Covariate inclusion criterion was p<0.05. Confounding was defined as a change of 20% or more in the computed risk estimate of the primary exposure, lift equipment usage frequency. Two-way effect modification between lift equipment usage frequency and other covariates was also assessed, with a p value of <0.05 being required for retention. Model fit was assessed with the quasi-likelihood information criterion (QIC) to determine the most appropriate models. SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

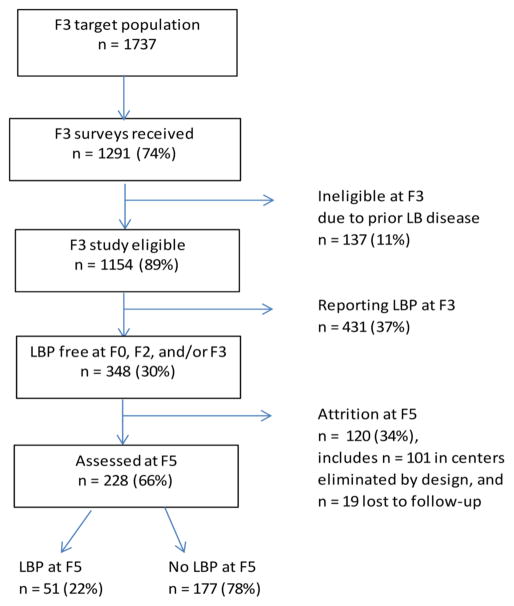

The response rate to the F3 survey was 74% (n=1291) (figure 1). Eleven per cent (n=137) of respondents were eliminated due to current low back disease/spine problems or prior back surgery, yielding n=1154 eligible study participants.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing participation in longitudinal cohort, nursing home workers, 2006–2013. LB, low back; LBP, low back pain.

The eligible respondents were mostly female (90.7%), with a mean age of 41.1 (SD=13.1) years, and a mean of 9.9 (SD=9.8) years seniority (table 1). Forty-eight per cent were identified as white and 41% were African-American. About one-half (52%) of respondents had a college education. Almost 60% had never smoked, almost one-third had chronic disease, and 69% had a BMI above normal. Twenty-eight per cent reported engaging in intense exercise three or more times per week. The distributions of gender, age and race were almost identical to those of the total clinical workforce (unpublished data provided by the company).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, medical history, health behaviours, job exposures, and exposures external to job, nursing home workers, overall and stratified by LBP status, and univariate robust Poisson regression models of LBP prevalence, 2008–2009 (F3: 2 years after SRHP implementation)

| Total | LBP at F3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Yes | No | Prevalence ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Total, n | 1154 | 431 | 723 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 41.1 (13.1) | 39.4 (13.3) | 42.2 (12.9) | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| Gender (n (%)) | |||||

| Male | 101 (9.3) | 30 (7.3) | 71 (10.5) | 1.0 | |

| Female | 988 (90.7) | 381 (92.7) | 607 (89.5) | 1.39 | 1.02 to 1.90 |

| Race (n (%)) | |||||

| White | 552 (47.8) | 326 (45.1) | 226 (52.4) | 1.0 | |

| Black | 468 (40.6) | 308 (42.6) | 160 (37.1) | 0.79 | 0.60 to 1.02 |

| Other/unknown | 134 (11.6) | 89 (12.3) | 45 (10.4) | 0.84 | 0.71 to 0.99 |

| BMI category (n (%)) | |||||

| Normal | 331 (30.3) | 130 (31.7) | 201 (29.4) | 1.0 | |

| Underweight | 14 (1.3) | 5 (1.2) | 9 (1.3) | 0.88 | 0.43 to 1.79 |

| Overweight | 350 (32.1) | 115 (28.2) | 235 (34.4) | 0.88 | 0.72 to 1.09 |

| Obese | 345 (31.6) | 137 (33.6) | 208 (30.4) | 1.02 | 0.84 to 1.24 |

| Extremely obese | 52 (4.8) | 21 (5.2) | 31 (4.5) | 1.08 | 0.74 to 1.58 |

| Marital status (n (%)) | |||||

| Married | 555 (49.4) | 185 (44.7) | 370 (52.2) | 1.0 | |

| Divorced | 195 (17.4) | 77 (18.6) | 118 (16.6) | 1.22 | 1.02 to 1.46 |

| Widowed | 39 (3.5) | 14 (3.4) | 25 (3.5) | 1.23 | 0.98 to 1.53 |

| Single | 334 (29.7) | 138 (33.3) | 196 (27.6) | 1.01 | 0.65 to 1.57 |

| Education | |||||

| Postgraduate | 45 (4.1) | 11 (2.7) | 34 (4.9) | 1.0 | |

| Some college or college graduate | 572 (51.8) | 217 (53.1) | 355 (51.1) | 1.52 | 0.90 to 2.57 |

| High school or less | 487 (44.1) | 181 (44.3) | 306 (44.0) | 1.55 | 0.92 to 2.62 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Previous back injury in past 12 months (n (%)) | 69 (6.0) | 54 (12.5) | 15 (2.1) | 2.24 | 1.90 to 2.63 |

| Chronic disease (n (%)) | 371 (32.6) | 131 (30.6) | 240 (33.8) | 0.91 | 0.77 to 1.07 |

| Health Behaviours | |||||

| Smoking status (n (%)) | |||||

| Never | 652 (57.6) | 232 (55.1) | 420 (59.0) | 1.0 | |

| Former | 232 (20.5) | 91 (21.6) | 141 (19.8) | 1.15 | 0.94 to 1.40 |

| Current | 249 (22.0) | 98 (23.3) | 151 (21.2) | 1.10 | 0.91 to 1.33 |

| Intense physical exercise frequency (n (%)) | |||||

| None | 253 (22.3) | 109 (25.6) | 144 (20.3) | 1.0 | |

| <1 time/week | 267 (23.5) | 110 (25.8) | 157 (22.1) | 0.89 | 0.72 to 1.10 |

| 1–2 times/week | 294 (25.9) | 106 (24.9) | 188 (26.5) | 0.78 | 0.62 to 0.97 |

| 3 times/week | 174 (15.3) | 61 (14.3) | 113 (15.9) | 0.73 | 0.57 to 0.95 |

| >3 times/week | 148 (13.0) | 40 (9.4) | 108 (15.2) | 0.58 | 0.43 to 0.80 |

| Job exposures | |||||

| Seniority (years) (mean (SD)) | 9.9 (9.8) | 9.7 (9.9) | 10.0 (9.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| Composite physical exposure (mean (SD)) | 11.9 (3.5) | 12.6 (3.3) | 11.5 (3.6) | 1.07 | 1.04 to 1.09 |

| Psychological job demands (mean (SD)) | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.1) | 1.21 | 1.13 to 1.29 |

| Decision latitude (mean (SD)) | 5.5 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.3) | 0.95 | 0.90 to 1.01 |

| Social support (mean (SD)) | 11.4 (2.3) | 10.9 (2.2) | 11.6 (2.2) | 0.91 | 0.88 to 0.94 |

| Physical assault in past 3 months (n (%)) | |||||

| None | 706 (62.3) | 216 (50.9) | 490 (69.1) | 1.0 | |

| 1–2 times | 254 (22.4) | 123 (29.0) | 131 (18.5) | 1.61 | 1.33 to 1.94 |

| 3 or more times | 173 (15.3) | 85 (20.1) | 88 (12.4) | 1.58 | 1.34 to 1.87 |

| Work safety (mean (SD)) | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.7 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.5) | 0.68 | 0.58 to 0.79 |

| Schedule control (mean (SD)) | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.5 (1.4) | 5.6 (1.4) | 0.98 | 0.93 to 1.04 |

| Frequency of lift usage (n (%)) | |||||

| Never/rarely | 374 (36.8) | 161 (41.1) | 1.0 | ||

| Sometimes/often/always | 642 (63.2) | 231 (58.9) | 0.86 | 0.73 to 1.02 | |

| Other | |||||

| Other paid job (n (%)) | 221 (19.6) | 83 (19.7) | 138 (19.4) | 1.01 | 0.84 to 1.22 |

| Work–family imbalance (mean (SD)) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.7) | 1.46 | 1.31 to 1.62 |

BMI, body mass index; LBP, low back pain; SRHP, safe resident handling programme.

There was a very slight decline in LBP prevalence from baseline (F0) through the 5–6-year (F5) follow-up survey (table 2). LBP cumulative incidence varied between 17% and 24% during the same time period but without a clear linear trend. There was no association between incident LBP in F2 or F3 and frequency of lifting device use at F2.

Table 2.

Prevalence and cumulative incidence* of low back pain (LBP), in nursing home workers, 2006–2013

| Survey period | Prevalence | Cumulative incidence* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total number of eligible participants† | LBP | Per cent (95% CI) | Total number of eligible participants‡ | New LBP | Per cent (95% CI) | |

| Baseline (F0) | 805 | 344 | 42.7 (39.3 to 46.2) | – | – | |

| 1 year (F2) | 1407 | 577 | 41.0 (38.4 to 43.6) | 307 | 72 | 23.5 (18.8 to 28.6) |

| 2 years (F3) | 1154 | 431 | 37.4 (34.5 to 40.2) | 348 | 58 | 16.7 (12.9 to 28.6) |

| 6 years (F5) | 2409 | 865 | 35.9 (34.0 to 37.9) | 228 | 51 | 22.4 (17.1 to 28.3) |

Cumulative incidence: first new pain report following prior survey without LBP.

Prevalence eligibility: respondents without prior back surgery or current treatment for low back disease or spinal problem.

Cumulative incidence eligibility: above plus no prior back injury or prior back pain on any earlier survey.

Prevalent LBP at 2-year follow-up

Thirty-seven per cent of respondents (n=431) reported LBP at 2-year follow-up (F3). In single predictor robust Poisson regression models, prevalent LBP was higher in women, as well as in those with previous back injury and those who identified as single (table 1). There was a small negative association with age. More frequent intense aerobic exercise appeared to be a protective health behaviour. The prevalence of LBP increased with occupational composite physical exposure score, psychological job demands, physical assault in the past 3 months and work–family imbalance. There was an inverse association with social support and work safety. Frequent lift usage and decision latitude were marginally protective.

In the multivariable model, LBP was positively associated with the composite physical exposure score, psychological job demands, physical assault in the workplace and prior back injury (table 3). Frequent lift usage and social support acted as protective factors. The model also included intense aerobic physical exercise with an apparent exposure-response trend and age as protective factors. There was no association with any other exposure or health behaviour, including those from prior surveys. The crude coefficient for the effect of lifting device frequency was not substantially changed by the inclusion of any variable into the model. That is, there were no confounders. Additionally, no effect modifiers were found.

Table 3.

Multivariable robust Poisson regression model of low back pain prevalence, nursing home workers, 2008–2009 (F3), n=1154; prevalence ratio (95% CI)

| Covariate | Prevalence ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 |

| Medical history | ||

| Previous back injury in past 12 months | 2.16 | 1.81 to 2.58 |

| Health Behaviours | ||

| Intense physical exercise frequency | ||

| None | 1.0 | |

| <1 time/week | 1.05 | 0.86 to 1.30 |

| 1–2 times/week | 0.84 | 0.67 to 1.04 |

| 3 times/week | 0.76 | 0.58 to 0.99 |

| >3 times/week | 0.72 | 0.53 to 0.98 |

| Job exposures | ||

| Composite physical exposure score | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.05 |

| Psychological job demands | 1.10 | 1.03 to 1.18 |

| Social support | 0.96 | 0.92 to 0.99 |

| Physical assault in past 3 months | ||

| None | 1.0 | |

| 1–2 times | 1.33 | 1.07 to 1.65 |

| 3 or more times | 1.38 | 1.15 to 1.65 |

| Frequency of lift usage | ||

| Rarely/never | 1.0 | |

| Sometimes/often/always | 0.83 | 0.71 to 0.96 |

Incident LBP at 6-year follow-up

One hundred and one individuals in the four centres who were eliminated from the cohort at F5 were LBP-free at all prior surveys and hence missing from the incident LBP analysis. Nineteen individuals were lost to follow-up. Therefore, 228 (66%) of the cohort members who were LBP-free in at least one prior survey were assessed at 6-year follow-up (F5) (figure 1). All but 4% (n=10) of them had submitted a 2-year follow-up (F3) survey. The average follow-up time for these participants was 4.5 years (range 3.5–5.5 years).

Participants who were lost to follow-up or eliminated by design in F5 did not differ from those who were analysed at F5 in most demographic, health or occupational characteristics. Those who were missing at F5 were more likely to be African-American and to be current smokers. They had a slightly lower psychological job demands score and slightly higher decision latitude, social support, work safety and schedule control indices. Individuals not followed up also had a slightly higher mean work–family imbalance score (2.4 vs 2.2) and were more likely to report frequent lift device usage (65% vs 57%), in comparison to those who were followed up.

Fifty-one (22.4%) at-risk workers reported LBP in the 6-year follow-up survey. A multivariable model was fitted which showed an increased risk in those with high work–family imbalance at F5 (relative risk (RR) 1.82 (95% CI 1.12 to 2.98)), and a protective effect from dichotomised frequent lift usage at F3 (RR=0.39 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.84)). There was no association with other exposure or health behaviour variables at any survey period, including assault and work–family imbalance at F3; no confounding by measured covariates; and no effect modification identified.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal cohort of nursing home workers, prevalent LBP declined only minimally in the first 2 years following the company-wide SRHP intervention. At 2-year follow-up, LBP prevalence was higher in those with more exposure to physical and psychosocial occupational risk factors. There were apparent protective effects of intense aerobic exercise frequency and lift usage frequency. However, equipment use prior to this time did not appear to convey protection from back pain after 2 years. In contrast, incident low-back pain at 6-year follow-up was reduced by earlier frequent lift usage and was also higher with current work–family imbalance.

Our 74% response rate at 2-year follow-up was greater than the baseline response rates in several other surveys of healthcare workers17,29,30 and smaller than the response rate in one other.19 Excluding those eliminated from the study by design at 6-year follow-up, the response rate among those who were LBP-free in prior surveys was 92%. This compares favourably with other published longitudinal or postintervention follow-up response rates, which range from 59%17 to 99%.31

The LBP prevalence observed in the current study (37–43%) is well within the wide range reported in other nursing populations.5 As others have reported, prior LBP was a predictor of later pain.32,33 We retained this variable to be conservative, although its interpretation is ambiguous. Recurrence itself is not distributed uniformly;34 it could serve as an indicator of past exposure, or it may represent a lowered pain threshold or pain tolerance.

High LBP persistence was noted here and has been observed in other nursing populations. For instance, approximately half of the nurses rated their LBP at a similar intensity over an 8-year period.35 Similarly, Swedish nurses had a high recurrence of LBP over a 3-year period and the largest number of episodes (mean=3) among all examined occupations (both white and blue collar).34

The most noteworthy result of this study is that frequent mechanical lift usage at 2 years postintervention was protective in preventing incident LBP about 4 years later. The fact that usage was assessed prior to the outcome in this longitudinal study gives credence to the association. The additional contribution of physical workload is also important. In addition to resident handling, nursing aides perform other tasks that load the low back, such as housekeeping and pushing and pulling loaded carts with food, medicine or other supplies. Andersen et al36 also found that lower physical effort at work predicted lower LBP incidence. The effect of recent physical assault, while not reported by others, is consistent with our earlier findings.23

No prior study that we could find has examined the effect of patient/resident handling devices on LBP for as many as 6 years postintervention. Our findings correspond well with a Markov cohort simulation model based on extant lift intervention studies.37 This model showed that it might take 3–4 years or more postintervention to manifest reductions in LBP symptoms, and the maximum impact would occur 6 years postintervention. Our results similarly suggest that workers may not experience reduced LBP risk until 2–6 years postintervention.

The reasons for this delay are not clear and could encompass organisational learning and/or individual practices. In this study setting, the SRHP elements were put into effect rather quickly, but it may be that work practices took some time to become consistent. Frequent lift use increased slightly over the 5-year period reported here, and certain self-reported reasons for not using devices decreased in frequency.38 There is some evidence that workers become more efficient and consistent in use of resident handling equipment over time.20,39,40 Obviously, further longitudinal research is indicated.

Frequent intense aerobic exercise was a protective factor against LBP in this population. Similar relationships have been reported by others for female nursing or healthcare workers generally,2,9 although not always consistently.6 There is also evidence of regular exercise having a protective effect for LBP in the general population.41 An alternative explanation for our results is that those with LBP were less able to engage in aerobic physical activity due to their pain. Surprisingly, there was no association with BMI in this population.

Work–family imbalance was positively associated with incident LBP at F5. It is possible that this construct served in this population as a partial surrogate for psychosocial stress, physical exhaustion or inability to withdraw from work (an aspect of overcommitment, as in the Effort–Reward Imbalance Model).42

Strengths and limitations of the study

The most important limitation is the lack of a concurrent control group. The original study design had called for surveying centres before programme implementation, which was staggered over time, so this would have provided some control observations. However, the programme moved ahead more quickly than had been anticipated, so by the time questionnaires could be distributed, there were relatively few centres left for implementation, and surveys could only be distributed concurrently with the programme start date (‘baseline’).

Exposures in this study were self-reported, so measurement error is possible. Of particular concern would be if those with LBP overestimated their physical exposures, in which case the true effect sizes may be larger than estimated here. Although some cohort members were observed for quantitative assessment of physical load at work,43 the number of persons observed was too small to compare with self-reported exposures. Hence, we cannot determine the direction of any possible bias in self-reported physical exposures. Similarly, self-reported lift usage frequency could be misclassified. However, as noted above, it is implausible that accuracy of self-reported lift usage at 2-year follow-up could be influenced by new LBP 4 years later.

Log-binomial models directly estimate the prevalence ratio. However, we opted to use robust Poisson regression modelling to estimate the prevalence ratio because of its better convergence properties.28 This latter method gives slightly different estimates than the log-binomial model.44

Another limitation is that there was no clinical examination or functional testing to assess LBP. Associations between particular clinical signs or syndromes and pain drawing characteristics are often weak.45,46 However, pain drawings have demonstrated test–retest reliability in patients with LBP.47

Participants who were lost to follow-up or eliminated by design in F5 were substantially similar to those who were analysed at F5. However, these two groups differed slightly in some characteristics, which may have been relevant to the outcome. The higher mean work–family imbalance score in those who were not followed up implies that a risk underestimation may have occurred. Also, since past studies have shown disproportionate leaving of work (or leaving in jobs with high ergonomic exposures) among those with musculoskeletal pain, this would tend to underestimate LBP incidence. This would additionally reduce statistical power for finding associations with secondary risk factors.

Owing to the study design, it is necessary to assume that pain reported for the first time in a survey is actually ‘new’ (incident) pain. This might not be true in a population with high occurrence and recurrence, such as nursing home workers. We have no way to test that assumption directly.

This study population had a nested structure (workers within facilities within a company). However, there was insufficient power to construct a random effects model with workplace as the higher level. It is unclear how much this would have influenced the results. In principle, uniform SRHP protocols and policies throughout the company should lessen the likelihood that the specific workplace would influence the effect of the intervention. On the other hand, in a subset of five of these facilities, differences in other practices and general work climate (communication, teamwork, supervisor support, agency staffing) were associated with the extent to which lifting devices were actually used and/or reduced biomechanical load.43

We cannot exclude all competing risks from the incident LBP analyses. Not all back pain is work-related, even in such a heavily exposed population as nursing aides.

Finally, the turnover rate of clinical staff during the first 2 years of the study ranged from 22% to 30%.48 Therefore, a ‘healthy worker survivor effect’ may have influenced the results, with underestimated effect sizes. (This might also explain the weak negative association between age and LBP.)

Particular study strengths were the large cohort that was enrolled, the good response rate in each survey and the 6-year postintervention follow-up interval. These strengths were not incidental; an exceptional degree of collaboration was required to provide long-term access to so many facilities and workers. In addition, the comprehensive survey instrument enabled the assessment of numerous potential confounders including demographic factors, medical history and personal health factors.

Conclusion

Use of resident lifting devices was found to reduce the occurrence of LBP symptoms in nursing home workers, 5–6 years after SRHP implementation. Frequent intense physical exercise and lower levels of other physical and psychosocial demands on the job also appear to protect against LBP. It may be several years before nursing homes and other healthcare facilities realise the full extent of desired results from comprehensive patient/resident handling programmes to prevent LBP.

What this paper adds.

Low back pain is prevalent among patient/resident handlers in healthcare settings.

While many studies have examined compensation claims after introduction of safe resident handling programmes (SRHP), none have examined low back pain symptoms for as many as 6 years postintervention.

Frequent mechanical lift usage at 2 years post-SRHP intervention appeared to be protective in preventing incident low back pain 5–6 years post-SRHP intervention.

It may be several years before healthcare facilities observe reductions in staff low back pain after implementation of safe patient/resident handling programmes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Genesis HealthCare Corporation for permission and access to carry out data collection, especially Donna LaBombard, Deb Slack-Katz and Mary Tess Crotty for liaising with individual nursing facilities, and many student research assistants for help with questionnaire distribution, data scanning and cleaning. Alicia Kurowski shared in-depth knowledge of these centres, job duties and programme features.

Funding This work was supported by the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH/CDC) (grant number U19-OH008857).

Footnotes

Disclaimer The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval University of Massachusetts Lowell Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributors JEG analysed the data, participated in data interpretation and drafted the manuscript. LP designed the study and the survey instrument, oversaw data collection, and participated in data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. RJG supervised data entry and quality control and provided critical statistical consulting support. All authors critically read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Engkvist IL, Hjelm EW, Hagberg M, et al. Risk indicators for reported over-exertion back injuries among female nursing personnel. Epidemiol. 2000;11:519–22. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bejia I, Younes M, Jamila HB, et al. Prevalence and factors associated to low back pain among hospital staff. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen JN, Holtermann A, Clausen T, et al. The greatest risk for low-back pain among newly educated female health care workers; body weight or physical work load? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen LL, Burdorf A, Fallentin N, et al. Patient transfers and assistive devices: prospective cohort study on the risk for occupational back injury among healthcare workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:74–81. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis KG, Kotowski SE. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders for nurses in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and home health care: a comprehensive review. Hum Factors. 2015;57:754–92. doi: 10.1177/0018720815581933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawson AP, McLennan SN, Schiller SD, et al. Interventions to prevent back pain and back injury in nurses: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:642–50. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.030643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alamgir H, Yu S, Fast C, et al. Efficiency of overhead ceiling lifts in reducing musculoskeletal injury among carers working in long-term care institutions. Injury. 2008;39:570–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.11.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park RM, Bushnell PT, Bailer AJ, et al. Impact of publicly sponsored interventions on musculoskeletal injury claims in nursing homes. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52:683–97. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tullar JM, Brewer S, Amick BC, III, et al. Occupational safety and health interventions to reduce musculoskeletal symptoms in the health care sector. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:199–219. doi: 10.1007/s10926-010-9231-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenfisch AL, Lipscomb HJ, Pompeii LA, et al. Musculoskeletal injuries among hospital patient care staff before and after implementation of patient lift and transfer equipment. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2013;39:27–36. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtermann A, Clausen T, Jorgensen MB, et al. Does rare use of assistive devices during patient handling increase the risk of low back pain? A prospective cohort study among female healthcare workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88:335–42. doi: 10.1007/s00420-014-0963-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yassi A, Cooper JE, Tate RB, et al. A randomized controlled trial to prevent patient lift and transfer injuries of health care workers. Spine. 2001;26:1739–46. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200108150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson A, Matz M, Chen F, et al. Development and evaluation of a multifaceted ergonomics programme to prevent injuries associated with patient handling tasks. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:717–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zadvinskis IM, Salsbury SL. Effects of a multifaceted minimal-lift environment for nursing staff: pilot results. West J Nurs Res. 2010;32:47–63. doi: 10.1177/0193945909342878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evanoff B, Wolf L, Aton E, et al. Reduction in injury rates in nursing personnel through introduction of mechanical lifts in the workplace. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44:451–7. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins JW, Wolf L, Bell J, et al. An evaluation of a “best practices” musculoskeletal injury prevention program in nursing homes. Inj Prev. 2004;10:206–11. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Wolf L, Evanoff B. Use of mechanical patient lifts decreased musculoskeletal symptoms and injuries among health care workers. Inj Prev. 2004;10:212–16. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg A, Kapellusch JM. Long-term efficacy of an ergonomics program that includes patient-handling devices on reducing musculoskeletal injuries to nursing personnel. Hum Factors. 2012;54:608–25. doi: 10.1177/0018720812438614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knibbe JJ, Friele RD. The use of logs to assess exposure to manual handling of patients, illustrated in an intervention study in home care nursing. Int J Ind Ergon. 1999;24:445–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurowski A, Boyer J, Fulmer S, et al. Changes in ergonomic exposures of nursing assistants after the introduction of a safe resident handling program in nursing homes. Int J Ind Ergon. 2012;42:525–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahiri S, Latif S, Punnett L, et al. An economic analysis of a safe resident handling program in nursing homes. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56:469–78. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurowski A, Buchholz B, Punnett L. A physical workload index to evaluate a safe resident handling program for nursing home personnel. Hum Factors. 2014;56:669–83. doi: 10.1177/0018720813509268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda H, Punnett L, Gore RJ. Musculoskeletal pain and reported workplace assault: a prospective study of clinical staff in nursing homes. Hum Factors. 2014;56:215–27. doi: 10.1177/0018720813508778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC. About adult BMI. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. (updated 15 May 2015). http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landsbergis PA, Schnall PL, Pickering TG, et al. Validity and reliability of a work history questionnaire derived from the Job Content Questionnaire. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:1037–47. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda H, Punnett L, Gore R, et al. Violence at the workplace increases the risk of musculoskeletal pain among nursing home workers. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:52–7. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.051474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bussing A. Social tolerance of working time scheduling in nursing. Work Stress. 1996;10:238–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deddens JA, Petersen MR. Approaches for estimating prevalence ratios. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:481, 501–6. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.034777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eriksen W, Bruusgaard D, Knardahl S. Work factors as predictors of intense or disabling low back pain; a prospective study of nurses’ aides. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:398–404. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.008482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jansen JP, Morgenstern H, Burdorf A. Dose-response relations between occupational exposures to physical and psychosocial factors and the risk of low back pain. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:972–9. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.012245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Josephson M, Lagerstrom M, Hagberg M, et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms and job strain among nursing personnel: a study over a three year period. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:681–5. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.9.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heap DC. Low back injuries in nursing staff. J Soc Occup Med. 1987;37:66–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harber P, Pena L, Hsu P, et al. Personal history, training, and worksite as predictors of back pain of nurses. Am J Ind Med. 1994;25:519–26. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700250406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abenhaim L, Suissa S, Rossignol M. Risk of recurrence of occupational back pain over three year follow up. Br J Ind Med. 1988;45:829–33. doi: 10.1136/oem.45.12.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maul I, Laubli T, Klipstein A, et al. Course of low back pain among nurses: a longitudinal study across eight years. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:497–503. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.7.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen LL, Clausen T, Persson R, et al. Perceived physical exertion during healthcare work and prognosis for recovery from long-term pain in different body regions: prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burdorf A, Koppelaar E, Evanoff B. Assessment of the impact of lifting device use on low back pain and musculoskeletal injury claims among nurses. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:491–7. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurowski A, Gore R, Mpolla N, et al. Use of resident handling equipment by nursing aides in long-term care: associations with work organization and individual level characteristics. Am J Safe Patient Handl Mov. 2016;6:16–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mechan P. Challenging the myth that it takes too long to use safe patient handling and mobility technology; a task time investigation. Am J Safe Patient Handl Mov. 2014;4:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoenfisch AL, Myers DJ, Pompeii LA, et al. Implementation and adoption of mechanical patient lift equipment in the hospital setting: the importance of organizational and cultural factors. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54:946–54. doi: 10.1002/ajim.21001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilsen TI, Holtermann A, Mork PJ. Physical exercise, body mass index, and risk of chronic pain in the low back and neck/shoulders: longitudinal data from the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:267–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1:27–41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurowski A, Gore R, Buchholz B, et al. Differences among nursing homes in outcomes of a safe resident handling program. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2012;32:35–51. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.21083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petersen MR, Deddens JA. A comparison of two methods for estimating prevalence ratios. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toomingas A. Characteristics of pain drawings in the neck-shoulder region among the working population. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72:98–106. doi: 10.1007/s004200050344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohlund C, Eek C, Palmbald S, et al. Quantified pain drawing in subacute low back pain. Validation in a nonselected outpatient industrial sample. Spine. 1996;21:1021–30. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199605010-00005. discussion 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohnmeiss DD. Repeatability of pain drawings in a low back pain population. Spine. 2000;25:980–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200004150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qin J, Kurowski A, Gore R, et al. The impact of workplace factors on filing of workers’ compensation claims among nursing home workers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]