Abstract

The effect of shift work on nurses’ sleep is well-studied, but there are other challenging aspects of health care work that might also affect the sleep of direct caregivers. This study examined the influence of the long-term care work environment on sleep quantity and quality of nursing assistants. A cross-sectional survey collected data from 650 nursing assistants in 15 long-term care facilities; 46% reported short sleep duration and 23% reported poor sleep quality. A simple additive index of the number of beneficial work features (up to 7) was constructed for analysis with Poisson regression. With each unit increase of beneficial work features, nursing assistants were 7% less likely to report short sleep duration and 17% less likely to report poor sleep quality. These results suggest that effective workplace interventions should address a variety of work stressors, not only work schedule arrangements, in order to improve nursing assistants’ sleep health.

Keywords: Job stress, Long-term care, Nursing assistants, Sleep quantity, Sleep quality, Work environment

Introduction

According to the National Health Interview Survey of 2004–2007, 30% of U.S. workers (approximately 40.6 million) experienced long-term sleep deprivation with average sleep duration of six or less hours per day.1 Short-term sleep deprivation can negatively affect an individual’s alertness, mood, attention, and ability to concentrate,2 while long-term sleep deprivation is associated with chronic fatigue,3 cardiovascular diseases,4 obesity and diabetes,5 and all-cause mortality.6 Health care workers provide continuous services around the clock; as a result, they are at risk for decreased sleep quantity and quality, continuous sleep deprivation, and cumulative sleep debt.3,7

Shift work, long work hours, and associated sleep problems and fatigue may influence the health and safety of both workers and patients.7,8 Fatigue resulting from shift work and poor sleep tends to reduce an employee’s ability to concentrate and decrease the quality of decision-making,9 increasing the possibility of errors and injuries. Rogers et al. (2004)10 reported that the likelihood of hospital nurses making an error was two to three times higher when they worked longer shifts. Sleep deprivation, sleepiness, and fatigue were consistently associated with nurse performance and patient safety.11–13 Wagstaff and Lie (2011)14 estimated from 14 high-quality epidemiology studies that accident rates increased 50%–100% for employees working long or irregular shifts.

Sleep quantity and quality has been better studied for nurses3,15 than for nursing assistants. Nursing assistants provides most of the front-line services in long-term care (LTC) facilities, so their ability to ensure resident safety and quality of care is essential. Poor sleep is a critical issue for nursing assistants. Eriksen, Bjorvatn, Bruusgaard, and Knardahl (2008)16 reported about 30% of nursing aides had poor sleep quality in Norway. Another study by Takahashi et al. (2008)17 reported a number of sleep problems among nursing home caregivers in Japan, including short sleep duration, poor sleep quality, and insomnia symptoms. Identified risk factors for sleep problems include socio-demographics such as age18,19; gender18; race20; marital status21; education22; and dependent family members.23 Sleep problems have also been linked to lifestyle factors such as smoking24 and physical activity25; and health conditions such as obesity,26 chronic diseases,27 and musculoskeletal pain.28

The association between work stressors and sleep has been documented. Charles et al. (2011)29 and Kashani, Eliasson and Vernalis (2012)30 reported that workers with higher perceived stress had significantly shorter sleep duration and worse sleep quality than workers with lower perceived stress. Work stress might directly affect employees’ sleep quality, and indirectly affect sleep quantity. For example, an employee may sacrifice sleep hours voluntarily for jobs or activities, and involuntarily from poor sleep quality. Nursing assistants face multiple work stressors in the LTC environment, including demanding work schedules,31 heavy workload and short staffing,32 workplace assaults,33 and low latitude in decision-making.34 These work stressors adversely impact nursing assistants’ health.31,35,36 Previous studies on sleep of nurses focused primarily on the effect of work schedules,3,7 an investigation of other work features associated with sleep quantity and quality for LTC nursing assistants is warranted.

The objective of this study was therefore to examine the influence of the organizational and psychological LTC work environment on sleep quantity and quality of nursing assistants. The study hypothesis was that more beneficial working conditions (employee perceived low physical and psychological demands, feeling safe in general and from violence at work, decision-making opportunities, support from coworkers and supervisors, and balance between work and family life) would improve nursing assistants’ sleep quality and/or quantity, after adjustment for other known risk factors.

Material and methods

Setting and subjects

As part of a larger research study of clinical caregivers, information was collected on nursing assistants’ work and health in a large chain of LTC facilities in the eastern United States. All centers were non-unionized skilled nursing facilities owned or managed by a single for-profit company. This study used cross-sectional survey data collected from a sample of 744 nursing assistants working in 15 LTC facilities located in Maryland and New England between January, 2008 and October, 2009. A non-probability convenience sampling method was used to recruit study participants. All full-time, part-time, and per-diem nursing assistants over 18 years old and hired directly by the company were eligible to participate.

Questionnaires were distributed and collected at the LTC facilities by the research team over a two to four day period to accommodate nursing assistants from different shifts and units. The research team members explained the study purpose and procedure, and potential benefits and risks to participants in person and requested them to sign the informed consent form. Participants were reassured that the employer would not receive any identifying information obtained, and they were given the option to take home the questionnaires to complete in private. Most participants completed questionnaires during break times and returned them in person. For others, such as third-shift and weekend workers, a pre-stamped and addressed-return envelope was provided. Compensation of $20 was offered in exchange for each completed questionnaire returned with a consent form. The study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Lowell Institutional Review Board (No. 06-1403).

Measurement of variables

Socio-demographics, lifestyle, and health

The questionnaire collected detailed information on nursing assistants’ socio-demographics, including age, gender, race, education, marital status, and responsibility for children and other dependents.

Information on smoking, sedentary behavior, obesity, chronic health conditions, and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) was collected. Sedentary behavior was defined as “exercise less than three times per week (for at least 20-min per session to work up a sweat).” BMI was calculated from self-reported weight and height, expressed as weight/height2. History of several chronic health conditions was assessed: diabetes, hypertension, elevated cholesterol level, and low back diseases or spine problems. Chronic health conditions were defined as “yes” for participants who reported any one of the above conditions. MSD symptoms were assessed for four body regions: low back, shoulder, wrist/forearm, and knee. MSD symptoms were defined as “yes” for participants who reported pain with severity ≥3 (scale 1–5) in any region.

Work environment

The questionnaire inquired about work characteristics from three physical domains (physical demands, physical safety, and violence at work) and five psychosocial domains (psychological demands, decision latitude, social support, schedule control, and work-family conflict), using items selected from standardized instruments. A 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree; disagree; agree; and strongly agree) was used for each item.

The psychological demands (4 items), decision latitude (7 items), and social support (4 items) subscales were selected from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ).37 The JCQ is a well-established instrument to measure different aspects of work characteristics, including subscales of physical demands (original 5 items), psychological demands (original 9 items), decision latitude (original 19 items), social support (original 11 items), and job insecurity (original 6 items).37 The JCQ subscales have demonstrated good validity and acceptable internal consistency in large study populations from six countries.37 Schedule control was measured with two items derived from Büssing (1996).38 Work-family conflict was measured with three items derived from Kopelman, Greenhaus, and Connolly (1983).39 Work Interference with Family Scale, which has demonstrated good reliability and validity in different populations.39

Physical demands subscale included 4 items from the JCQ and one item written by the research team. Physical safety was measured with two items from Griffin and Neal (2000),40 along with two items developed by the investigators. Violence at work was measured with one item: “In the past 3 months, have you been hit, kicked, grabbed, shoved, pushed or scratched by a patient, patient’s visitor or family member while you were at work?” The questionnaire also collected information about work shift schedule (day, evening, night, or rotating), shift length, work hours/two weeks, and working other paid jobs (yes or no).

Instrument internal consistency was assessed in these study participants with Cronbach’s alpha (α). Four subscales: physical demands (α = 0.82), social support (α = 0.77), schedule control α = 0.74) and work-family conflict (α = 0.78), had acceptable reliability (α ≥ 0.7); and three subscales: physical safety (α = 0.45), psychological demands (α = 0.47), and decision latitude (α = 0.61), had lower values (α < 0.7). Previous studies with hospital nurses41,42 have also shown lower reliability of psychological demands and decision latitude subscales; this may be due in part to the fact that the demands scale also reflects physical workload for some workers,43,44 and similarly that decision latitude scale has two dimensions, skill discretion and decision authority.

Based on bivariate correlations, schedule control was not associated with either sleep quantity or quality, so was excluded from further analysis. The work characteristics (physical demands, physical safety, violence at work, psychological demands, decision latitude, social support, and work-family conflict) were moderately to strongly correlated with each other and significantly associated with sleep quantity, quality, or both. To avoid co-linearity, we constructed an index of those variables associated with sleep quantity and/or quality.34,45 Each one was dichotomized as “low” (0) or “high” (1) at its median value. For example, social support was dichotomized at its median value of 11 into low (4–11) and high support (12–16). The sum of those dichotomous indicators became the index of beneficial work features, i.e.: low physical demands, high physical safety, low violence at work, low psychological demands, high decision latitude, high social support, and low work-family conflict. The working condition index ranged from 0 to 7 (higher score representing better working conditions). The working condition index, or variations on it, has demonstrated strong associations with intention to leave work as well as with health behaviors in this workforce.34,45

Sleep quantity and quality

Both sleep quantity and quality were assessed from participants’ subjective reports. The measure of sleep quantity indicated participants’ typical amount of sleep per 24-h period during the work week (6 h or less; 7–8 h; 8–9 h; 9–10 h; and 10 h or more). For these analyses, sleep duration was dichotomized as >6 h per day, versus ≤6 h per day (“short sleep duration”).1,46 The participants’ subjective quality of sleep on a typical night was measured in five categories (good; fairly good; fairly poor; poor; can’t say). This item was modified from the sleep quality question from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).47 Sleep quality was dichotomized as good (good; fairly good), versus poor (poor; fairly poor).48

Data analysis

Poisson regression with robust variance estimation was used to calculate prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).49 Two multivariable regression models were built; one for short sleep duration and one for poor sleep quality. We began with a block of known risk factors for sleep problems: age, gender, race, marital status, education, having children, elderly or disabled dependents, smoking, sedentary behavior, BMI, chronic health conditions, MSDs, and shift work, shift length, weekly work hours, and other paid jobs. Those variables whose coefficients had p values ≤0.10 for either outcome were retained in both of the first models, to facilitate comparison between outcomes. The index of favorable work environment conditions was added for the second models. All analyses were done using SPSS software release 20.0.0 on a Windows 7 operating system.

Results

Descriptive analyses

A total of 744 nursing assistants from the 15 LTC facilities (73% of eligible employees) completed questionnaires. Respondents with missing data on both sleep quantity and quality were excluded from analysis (n = 94). The excluded workers were less likely to be current smokers or to have chronic health conditions and were more likely to be in the “other” racial group and to work a second paid job. They reported lower physical demands and schedule control, and higher physical safety and social support, than those remained in this analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographics, lifestyle and health, work characteristics, and sleep quantity and quality among nursing assistants.

| Cases (n = 650) |

Excluded cases (n = 94) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.5 ± 13.7 | 38.6 ± 11.4 |

| Gender (female) | 93.0% | 90.9% |

| Race** | ||

| White | 40.5% | 29.8% |

| Black | 50.5% | 44.7% |

| Others | 9.1% | 25.5% |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 31.3% | 31.9% |

| Married | 47.7% | 48.4% |

| Widowed or divorced | 20.9% | 19.8% |

| Education (years) | 12.6 ± 1.3 | 12.8 ± 1.7 |

| Children responsibility (yes) | 58.7% | 65.2% |

| Other dependent responsibility (yes) | 17.4% | 17.4% |

| Smoking (yes)* | 25.8% | 17.8% |

| Sedentary behavior (yes) | 44.5% | 40.4% |

| BMI | 28.9 ± 6.7 | 28.8 ± 5.6 |

| Chronic health conditions (yes)* | 31.8% | 21.5% |

| MSDs (yes) | 44.8% | 41.5% |

| Shift work | ||

| Day | 40.9% | 48.8% |

| Evening | 21.7% | 23.3% |

| Night | 16.5% | 8.1% |

| Rotating | 20.9% | 19.8% |

| Shift length (hours/shift) | 8.1 ± 2.0 | 8.1 ± 1.1 |

| Work hours/two weeks | 66.8 ± 23.6 | 72.3 ± 22.4 |

| Other paid jobs (yes)** | 16.8% | 29.0% |

| Physical demands** | 12.8 ± 3.4 | 11.7 ± 3.4 |

| Physical safety** | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.5 |

| Violence at work | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.7 |

| Psychological demands | 10.9 ± 1.9 | 10.6 ± 1.9 |

| Decision latitude | 66.2 ± 9.7 | 67.5 ± 12.1 |

| Social support** | 10.9 ± 2.4 | 11.9 ± 2.1 |

| Schedule control* | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 5.3 ± 1.4 |

| Work-family conflict | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.6 |

| Sleep quantity (≤6 h/day) | 45.5% | – |

| Sleep quality (poor) | 22.6% | – |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

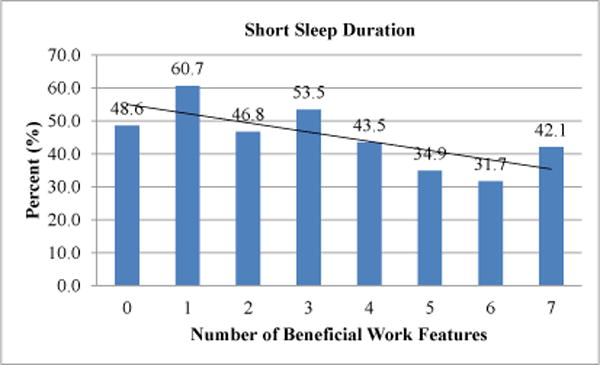

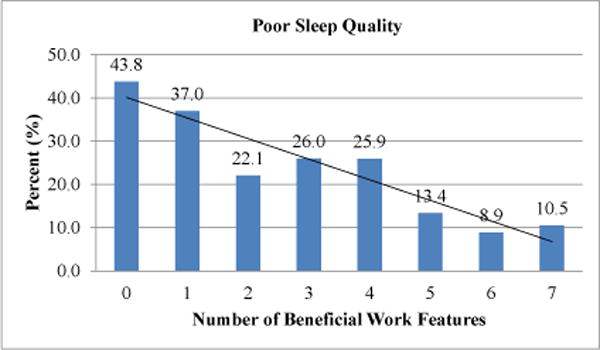

Among the participants, 46% reported short sleep duration (≤6 h/day) and 23% reported poor sleep quality. About half (51%) rated in the upper half (“4” to “7”) of the working condition index. Only 6% of participants reported no beneficial features. The prevalence of short sleep duration among nursing assistants decreased with the number of beneficial work features (Fig. 1), as did the prevalence of poor sleep quality (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Association between short sleep duration and working condition index.

Note. Prevalence of short sleep duration reduced with increase of the number of beneficial work features (linear trend p<0.05)

Fig. 2.

Association between poor sleep quality and working condition index.

Note. Prevalence of poor sleep quality reduced with increase of the number of beneficial work features (linear trend p<0.01)

Multivariable analyses

In the modified Poisson regression modeling, the index of beneficial work features retained a protective effect for both short sleep duration and poor sleep quality after adjustment for other known risk factors (Table 2). With each unit increase in beneficial work features, the prevalence of short sleep duration was reduced by 7%, and the prevalence of poor sleep quality by 17%. Night shift work, working other paid jobs, and having elderly or disabled dependents significantly contributed to short sleep duration. Nursing assistants suffering MSDs reported more poor sleep quality than those without. Deleting known risk factors with p values between 0.05 and 0.10 had little effect on the estimated effect of the working condition index in either of the second models.

Table 2.

Poisson regression models predicting short sleep duration and poor sleep quality among nursing assistants.

| Predictors | Short sleep duration

|

Poor sleep quality

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||||

| PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | PR | 95% CI | |

| Gender (male) | 1.18 | 0.83–1.68 | 1.15 | 0.78–1.69 | 1.84* | 1.04–3.26 | 1.82* | 1.03–3.22 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Black | 0.81* | 0.66–0.99 | 0.78* | 0.63–0.95 | 0.62* | 0.43–0.89 | 0.71a | 0.50–1.01 |

| Others | 1.13 | 0.82–1.56 | 1.23 | 0.90–1.67 | 0.44 | 0.14–1.34 | 0.82 | 0.38–1.76 |

| Children | 1.19a | 0.97–1.46 | 1.16 | 0.95–1.41 | 1.07 | 0.75–1.53 | 1.17 | 0.84–1.65 |

| Dependents | 1.22a | 0.98–1.51 | 1.26* | 1.02–1.56 | 1.14 | 0.74–1.78 | 1.25 | 0.83–1.87 |

| Smoking | 1.09 | 0.89–1.33 | 1.12 | 0.92–1.37 | 1.38a | 0.95–1.98 | 1.27 | 0.89–1.81 |

| MSDs | 1.16 | 0.96–1.41 | 1.11 | 0.91–1.35 | 1.57* | 1.09–2.26 | 1.44* | 1.02–2.04 |

| Shift work | ||||||||

| Day (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Evening | 0.88 | 0.67–1.16 | 0.91 | 0.69–1.20 | 0.82 | 0.51–1.31 | 0.89 | 0.55–1.42 |

| Night | 1.57** | 1.26–1.96 | 1.57** | 1.26–1.95 | 1.01 | 0.59–1.74 | 1.08 | 0.67–1.74 |

| Rotating | 1.09 | 0.82–1.44 | 0.95 | 0.69–1.29 | 1.04 | 0.64–1.68 | 0.97 | 0.59–1.58 |

| Shift length | 1.01 | 0.96–1.06 | 1.02 | 0.97–1.08 | 1.07a | 0.99–1.15 | 1.07a | 0.99–1.15 |

| Other jobs | 1.40** | 1.14–1.72 | 1.47** | 1.18–1.82 | 0.97 | 0.62–1.53 | 0.94 | 0.60–1.48 |

| WCI | 0.93** | 0.88–0.98 | 0.83** | 0.76–0.90 | ||||

WCI = Working Condition Index; PR = Prevalence ratio.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Variables not included in either Model 1 (p > 0.10 for both outcomes): age, marital status, education, sedentary behavior, BMI, chronic health conditions, and weekly work hours.

Discussion

In this large study of LTC nursing assistants, almost half of the respondents (46%) reported short sleep duration (≤6 h/day). This is a higher prevalence than in all U.S. workers (30%) in the National Health Interview Survey1 and in U.S. nurses in the National Nurses’ Health Study (30%).50 In addition, over 20% of LTC nursing assistants reported poor sleep quality, which is similar to previously reported data on nursing home caregivers.17 These results are of concern because poor or deprived sleep among nursing staff could represent a threat to resident safety and quality of resident care, as well as to worker health and safety.8,11–13

We examined seven specific work features in the LTC environment (employee perceived low physical and psychological demands, feeling safe in general and from violence at work, decision-making opportunities, support from coworkers and supervisors, and balance between work and family life) which have already been shown to affect mental health and intention to leave the job.34 The combination of these selected job features, each framed in beneficial terms, had an important association with sleep outcomes. After adjustment for other known risk factors of sleep, with each increase in the number of these job features, nursing assistants were 7% less likely to experience short sleep duration and 17% less likely to experience poor sleep quality. These results are consistent with prior reports of associations between job stress and sleep quality in different occupations.29,30,51 These work features may affect nursing assistants’ sleep quality directly and affect sleep quantity indirectly through the effect on sleep quality.

Many of these work features are amenable to change in the LTC work environment. Increasing worker decision-making, improving labor–management interaction, reducing violence or unsafe environment, and promoting better balance of work and family life might help promote the sleep quantity and quality of these workers. Possible strategies to improve working conditions in LTC environment include: Give more opportunities for front-line workers to get involved in making decisions about resident care and center changes; establish an employee-recognition program; acknowledge staff publicly or privately for working extra time or on holidays; promote a safer work environment (e.g., through safe-resident handling equipment and policies); implement violence prevention programs; and genuinely listen to the experiences and opinions of employees when difficulties arise from their work or family life. For example, increased control over work assignments and supervisors’ supportive behaviors played important roles in buffering the effect of work-family conflict on employees’ health and well-being.52,53

As expected, in our study night shift work was also associated with short sleep duration. Night work requires sleep during the biological day; the resulting misalignments between internal circadian time and work-rest schedules often lead to reduced sleep hours.1,54 Family and other responsibilities may interfere with daytime sleep, especially in a group of predominantly female workers, which might plausibly explain our findings that many nursing assistants with elderly or disabled dependents had short sleep duration.

We also found that poor sleep quality was more prevalent among nursing assistants suffering MSDs, which may be a bidirectional relationship.55 Nursing assistants in LTC are prone to experiencing MSDs due to resident lifting, repositioning, and transferring,56 as well as other work stressors.33 Compromised sleep quality is a known consequence of chronic pain,57 and individuals with poor sleep quality usually perceive pain to be more intense.58 Further, individuals with MSDs that interfere with sleep often have worse MSD outcomes.28

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. The generalizability of the results may be limited because these 15 LTC facilities were all operated by a single for-profit corporation and none were unionized. A follow-up study using a more nationally representative random sample would improve the generalizability of the findings. There might be selection bias due to the difference of work characteristics between the participants included and excluded from final analyses; however, exclusions were made blinded to exposure levels and the excluded cases only represented a small number of participants (12%). The cross-sectional design does not allow us to draw causal relationships; future analyses of longitudinal data will be needed to verify the study findings. The strengths of this study include the large number of nursing assistants from multiple workplaces, the good response rate, the comprehensive range of work environment features assessed, and the consideration of potential confounders in data analyses.

Conclusions

This quantitative cross-sectional study found that nursing assistants’ sleep quantity and quality were closely associated with the LTC work environment. Specifically, workers with more beneficial work features had longer sleep duration and better sleep quality. Considering the potential impact of nursing assistants’ sleep on resident safety and quality of care, as well as on their own health, this finding deserves attention from LTC managers and policy-makers.

Traditional health promotion practice focused on individual behavior changes, but newer interventions address work environment influences on health behaviors (e.g., see Refs. 59, 60). As Punnett et al. (2009)61 suggested, in addition to addressing individual behaviors, workplace health promotion programs must address work organization features to be effective. Workplaces that seek to be health-promoting should build better interpersonal relationships, involve front-line workers in decision-making, take measures to reduce violence and unsafe environment, and support a better balance of work and family life.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the CPH-NEW Research Team working together to collect the questionnaire data. We express our sincere thanks to Dr. Angela Nannini for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding: The Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace is supported by Grant number 1 U19 OH008857 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC). This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIOSH.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Lowell Institutional Review Board (No. 6-1403).

References

- 1.Luckhaupt SE, Tak S, Calvert GM. The prevalence of short sleep duration by industry and occupation in the National Health Interview Survey. Sleep. 2010;33(2):149–159. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wehrens SM, Hampton SM, Kerkhofs M, Skene DJ. Mood, alertness, and performance in response to sleep deprivation and recovery sleep in experienced shiftworkers versus non-shiftworkers. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(5):537–548. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.675258. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2012.675258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geiger-Brown J, Rogers VE, Trinkoff AM, Kane RL, Bausell RB, Scharf SM. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(2):211–219. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.645752. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2011.645752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullington JM, Haack M, Toth M, Serrador JM, Meier-Ewert HK. Cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;51(4):294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.10.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNeil J, Doucet É, Chaput JP. Inadequate sleep as a contributor to obesity and type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(2):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.02.060. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caruso CC. Negative impacts of shift work and long work hours. Rehabil Nurs. 2014;39(1):16–25. doi: 10.1002/rnj.107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rnj.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger AM, Hobbs BB. Impact of shift work on the health and safety of nurses and patients. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10(4):465–471. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.465-471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/06.CJON.465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott LD, Arslanian-Engoren C, Engoren MC. Association of sleep and fatigue with decision regret among critical care nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2014;23(1):13–23. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2014191. http://dx.doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Scott LD, Aiken LH, Dinges DF. The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Aff. 2004;23:202–212. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caruso CC, Hitchcock EM. Strategies for nurses to prevent sleep-related injuries and errors. Rehabil Nurs. 2012;35(5):192–197. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00047.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2010.tb00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockley SW, Barger LK, Ayas NT, Rothschild JM, Czeisler CA, Landrigan CP, The Harvard Work House, Health and Safety Group Effects of health care provider work hours and sleep deprivation on safety and performance. Joint Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(suppl 11):7–18. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers AE. The effects of fatigue and sleepiness on nurse performance and patient safety. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; pp. 20081036–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagstaff AS, Lie JAS. Shift and night work and long working hours – a systematic review of safety implications. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37:173–185. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3146. http://dx.doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zverev YP, Misiri HE. Perceived effects of rotating shift work on nurses’ sleep quality and duration. Malawi Med J. 2009;21(1):19–21. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v21i1.10984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksen W, Bjorvatn B, Bruusgaard D, Knardahl S. Work factors as predictors of poor sleep in nurses’ aides. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(3):301–310. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0214-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00420-007-0214-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi M, Iwakiri K, Sotoyama M, et al. Work schedule differences in sleep problems of nursing home employees. Appl Ergon. 2008;39:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green MJ, Espie CA, Hunt K, Benzeval M. The longitudinal course of insomnia symptoms: Inequalities by sex and occupational class among two different age cohorts followed for 20 years in the west of Scotland. Sleep. 2012;35(6):815–823. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1882. http://dx.doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marquié JC, Folkard S, Ansiau D, Tucker P. Effects of age, gender, and retirement on perceived sleep problems: results from the VISAT combined longitudinal and cross-sectional study. Sleep. 2012;35(8):1115–1121. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.5665/sleep.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomfohr L, Pung MA, Edwards KM, Dimsdale JE. Racial differences in sleep architecture: the role of ethnic discrimination. Biol Psychol. 2012;89(1):34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troxel WM, Buysse DJ, Matthews KA, et al. Marital/cohabitation status and history in relation to sleep in midlife women. Sleep. 2010;33(7):973–981. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.7.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavara C, Theleritis C, Psarros C, Soldatos C, Tountas Y. Insomnia and its correlates in a representative sample of the Greek population. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:531. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-531. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KC, Yiin JJ, Lin PC, Lu SH. Sleep disturbances and related factors among family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3816. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.3816. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Paterson JL, Dorrian J, Clarkson L, Darwent D, Ferguson SA. Beyond working time: factors affecting sleep behavior in rail safety workers. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;45(suppl):32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2011.09.022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farnsworth JL, Kim Y, Kang M. Sleep disorders, physical activity, and sedentary behavior among U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Phys Act Health. 2015 doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0251. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buscemi D, Kumar A, Nugent R, Nugent K. Short sleep times predict obesity in internal medicine clinic patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(7):681–688. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, Walsh J. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi M, Matsudaira K, Shimazu A. Disabling low back pain associated with night shift duration: sleep problems as a potentiator. Am J Ind Med. 2015 doi: 10.1002/ajim.22493. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charles LE, Slaven JE, Mnatsakanova A, et al. Association of perceived stress with sleep duration and sleep quality in police officers. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2011;13(4):229–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashani M, Eliasson A, Vernalis M. Perceived stress correlates with disturbed sleep: a link connecting stress and cardiovascular disease. Stress. 2011;15:45–51. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2011.578266. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2011.578266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C, Lipscomb J, Trinkoff A. Demanding work schedules and mental health in nursing assistants working in nursing homes. Work Stress. 2004;18(4):292–304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02678370412331320044. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lapane KL, Hughes CM. Considering the employee point of view: perceptions of job satisfaction and stress among nursing staff in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.05.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miranda H, Punnett L, Gore R, Boyer J. Violence at the workplace increases the risk of musculoskeletal pain among nursing home workers. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68:52e57. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.051474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oem.2009.051474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Punnett L, Gore R, The CPHNEW Research Team Relationships among employees’ working conditions, mental health, and intention to leave in nursing homes. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33(1):6–23. doi: 10.1177/0733464812443085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0733464812443085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muntaner C, Li Y, Xue X, O’Campo P, Chung HJ, Eaton WW. Work organization, area labor-market characteristics, and depression among U.S. nursing home workers: a cross-classified multilevel analysis. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):392–400. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muntaner C, Li Y, Xue X, Thompson T, Chung H, O’Campo P. County and organizational predictors of depression symptoms among low-income nursing assistants in the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1454–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.03.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karasek RA, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman ILD, Bongers PM, Amick BC. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–355. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Büssing A. Social tolerance of working time scheduling in nursing. Work Stress. 1996;10:238–250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02678379608256803. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopelman RE, Greenhaus JJ, Connolly TF. A model of work, family, and interrole conflict: a construct validation study. Organ Behav Hum Perform. 1983;32:198–215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(83)90147-2. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffin MA, Neal A. Perceptions of safety at work: a framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(3):347–358. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choobineh A, Ghaem H, Ahmedinejad P. Validity and reliability of the Persian (Farsi) version of the Job Content Questionnaire: a study among hospital nurses. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(4):335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griep RH, Rotenberg L, Vasconcellos AGG, Landsbergis P, Comaru CM, Alves MGM. The psychometric properties of demand-control and effort-reward imbalance scales among Brazilian nurses. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2009;82:1163–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0460-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00420-009-0460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi B, Kawakami N, Chang S, et al. A cross-national study on the multidimensional characteristics of the five-item psychological demands scale of the Job Content Questionnaire. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(2):120–132. doi: 10.1080/10705500801929742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi B, Kurowski A, Bond MA, et al. Occupation-differential construct validity of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) psychological job demands scale with physical job demands items: a mixed methods research. Ergonomics. 2012;55(4):425–439. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2011.645887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miranda H, Gore R, Boyer J, Nobrega S, Punnett L. Health behaviors and overweight in nursing home employees: contribution of workplace stressors and implications for worksite health promotion. Scientific World Journal. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/915359. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qiu C, Gelaye B, Fida N, Williams MA. Short sleep duration, complaints of vital exhaustion and perceived stress are prevalent among pregnant women with mood and anxiety disorders. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-12-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caska CM, Hendrickson BE, Wong MH, Ali S, Neylan T, Whooley MA. Anger expression and sleep quality in patients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(3):280–285. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819b6a08. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819b6a08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barros AJD, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel SR, Ayas NT, Malhotra MR, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004;27(3):440–444. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knudsen H, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Job stress and poor sleep quality: data from an American sample of full-time workers. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(10):1997–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly EL, Moen P, Tranby E. Changing workplaces to reduce work-family conflict: schedule control in a white-collar organization. Am Sociol Rev. 2011;76:265–290. doi: 10.1177/0003122411400056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0003122411400056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kossek EE, Pichler S, Bodner T, Hammer LB. Workplace social support and work-family conflict: a meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work-family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers Psychol. 2011;64:289–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perkins L. Is the night shift worth the risk? RN. 2001;64(8):65–68. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koffel E, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Leverty D, Polusny MA, Krebs EE. The bidirectional relationship between sleep complaints and pain: analysis of data from a randomized trial. Health Psychol. 2015 doi: 10.1037/hea0000245. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis KG, Kotowski SE. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders for nurses in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and home health care: a comprehensive review. Hum Factors. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0018720815581933. Advanced Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kelly GA, Blake C, Power CK, O’keeffe D, Fullen BM. The association between chronic low back pain and sleep: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(2):169–181. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f3bdd5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f3bdd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kundermann B, Krieg JC, Schreiber W, Lautenbacher S. The effect of sleep deprivation on pain. Pain Res Manag. 2004;9(1):25–32. doi: 10.1155/2004/949187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ball K, Timperio AF, Crawford DA. Understanding environmental influences on nutrition and physical activity behaviors: where should we look and what should we count? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duncan MJ, Spence JC, Mummery WK. Perceived environment and physical activity: a meta-analysis of selected environmental characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-2-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Punnett L, Cherniack M, Henning R, Morse T, Faghri P, The CPH-NEW Research Team A conceptual framework for integrating workplace health promotion and occupational ergonomics programs. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(suppl 1):16–25. doi: 10.1177/00333549091244S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]